A Claim in 140 Characters: Live-Tweeting in the Composition Classroom

Shannon Draucker, Boston University

By live-tweeting course texts and class presentations, first-year composition students develop fundamental writing skills including thesis formation, evidence incorporation, and peer review.

Student 1: “Joanne seems like quite the outcast…how did a lawyer end up in Bohemia?”

Student 2: “And that too, a female lawyer! But also, weren’t bohemians actually quite

wealthy?”

Student 3: “interesting how she’s an outcast of these outcasts.”

Student 4: “literally same, like I think her only ‘edgy’ characteristic is that she’s not

straight.”

At first, the above conversation might seem rather unremarkable — typical of a discussion in a freshman composition class. Yet, this exchange did not take place in class or even in person, but rather on Twitter. In my Fall 2016 first-year writing seminar at Boston University, titled “La vie Bohème: Art and Counterculture from the Nineteenth Century to the Present,” I instructed my students to “live-tweet” as they watched Christopher Columbus’s 2005 film version of Rent, one of our course texts. After explaining that “live-tweeting” is a popular practice among audience members and critics at film festivals, orchestra concerts, and even academic conferences, I urged my students to compose five to seven tweets in response to the film, using the hashtag “#WR100F8,” our course number (Fig. 1). While I initially assigned the live-tweeting exercise as a fun, avant-garde diversion from our regular work, live-tweeting actually helped my students achieve some of the central compositional goals of the course: crafting arguments, substantiating their claims with evidence, and responding to the writing of others.

Figure 1: The above image depicts a screenshot of my introductory tweet to my students, which reads “Hello, BU WR 100 students (section F8!) Tweet using the hashtag #WR100F8.” It shows my name (Shannon B. Draucker), the Twitter handle (@profdrauck) for the account I created for the assignment, and a photo of me.

Teaching with Twitter: Current Conversations

Though oriented thematically around questions of alternative art culture and bohemian life, my course was at base a freshman composition class.[1] As described in the Writing Program’s syllabus template, students in WR 100 should achieve several aims: “craft substantive, motivated, balanced academic arguments; write clear, correct, coherent prose; read with understanding and engagement; plan, draft, and revise efficiently and effectively; evaluate and improve… reading and writing processes; respond productively to the writing of others; express yourself verbally and converse thoughtfully about complex ideas” (“WR 100 Syllabus Template” 2014). Live-tweeting enriched my students’ development as writers and helped them work towards several of these aims.

Pedagogy scholars have outlined uses of Twitter in K-12, undergraduate, and graduate classroom settings. Adeline Koh and Mark Sample argue that live-tweeting can encourage “backchannel conversations” between students who wish to continue their class conversations or ask each other questions that they might be hesitant to pose in person (Koh 2014; Sample 2010). Though Stephen J. Jacquemin and others worry that Twitter might inhibit “active discussion and feedback,” Brian Croxall suggests that Twitter offers shyer students a less intimidating venue in which to contribute (Jacquemin et al. 2014, 22-27; Croxall 2010). Jevon D. Hunter and Heidie Jean Caraway propose that Twitter provides an easily accessible space for students to take notes, reflect on what they are reading, and track their immediate responses to a text (Hunter and Caraway 2014, 76-82). Sarah Townsend examines how literature students can use Twitter to better understand the formal features of experimental novels like James Joyce’s Ulysses (Townsend 2017). Tracy Hawkins identifies Twitter as a tool for feminist pedagogy, as it encourages students to participate in activist discourses and consciousness-raising efforts that occur online, though she also emphasizes that instructors must work to “mentor their students about how to avoid being victims or perpetrators of online injustices” (Hawkins 2015, 167). Others have identified how Twitter can teach students to be social media-savvy and to develop transferable skills (Greenhow and Gleason 2012, 464-478; Nicholson and Galguera 2013, 7).

I found that Twitter offered my students a venue in which to share their more casual, impressionistic responses to our course texts and to communicate their immediate reactions and emerging insights with each other. I, in turn, was able to build on their “backchannel” conversations in order to propel our discussion the following day in class. Moreover, though most of my students were already technologically savvy, live-tweeting gave them a chance to practice their social media skills and use Twitter more creatively by incorporating GIFs and other images, “liking” each other’s posts, and using hashtags (Fig. 2). Live-tweeting also allowed my students to share their personalities and senses of humor, as well as communicate their enthusiasm for the material (Fig. 3). This space to get to know each other and engage thoughtfully with each other’s ideas was particularly valuable for a small, seminar-style class of freshmen just entering university life.

Figure 2: This image depicts a screenshot of a student’s tweet, which reads, “OMG they just kissed!! #tears #wr100f8.” It includes a GIF of two cats kissing.

Figure 3: This image depicts a screenshot of a student’s tweet, which reads “Full on belting Seasons of Love right now #WR100F8 I love musicalsss.” The image also shows that this tweet has received “4 Likes.” It also includes another student’s reply, which reads, “I think it is an interesting song choice esp. because the film cycles thru all the seasons of the year and comes full circle!” In this and all subsequent images, I have redacted the students’ names, Twitter handles, and photos in order to protect their privacy.

Live-Tweeting in #WR100F8

Live-tweeting requires that students create their own accounts on Twitter. As I was committed to making our Twitter feed a safe space for the students, I held a class discussion before the first Twitter assignment to address appropriate Internet conduct. I insisted that my students treat each other with the same respect on Twitter that they did in class. I also allowed my students to create new Twitter accounts (other than their personal ones) and to use pseudonyms that only their peers and I would know. They could also make their accounts “protected,” subject to their approval of individual “followers” (their classmates and myself). About half of my students created new Twitter accounts for the assignment, though this includes students who did not previously have a Twitter account, and two students “protected” their tweets. No one chose to create a pseudonym.[2] I also tweeted under an account I created for the purpose (@profdrauck), which I used to generate my own live-tweets in response to the course texts and respond to students’ tweets.

I directed my students to live-tweet on three occasions. I first instructed them to live-tweet as they viewed a recorded production of Giacomo Puccini’s 1895 opera La Bohème. Though I initially introduced the assignment in class, I also sent instructions to my students via email:

As you watch the video, generate 5-6 live-tweets with observations, quotations, questions, and points of interest from the film.

Remember to use the hashtag #WR100F8 and #LaBoheme if you’d like, and follow me at @profdrauck. Let me know if you have any questions. The conversations you have on this platform will spark our conversation on Monday.

I directed students to live-tweet for a second time several weeks later, when they were watching Columbus’s Rent. After realizing that their La Bohème tweets were insightful, but not particularly interactive, I urged students to engage with each other’s tweets more deliberately:

Please respond to at least two of your classmates’ tweets (by hitting “reply” on Twitter). This will allow you to get the discussion started before class even begins.

Our third Twitter exercise was optional. I invited students to live-tweet each other’s in-class presentations about their third (and final) paper for the course. They could quote or paraphrase their peers’ statements, pose questions, or offer suggestions that the presenter could read later.

All in all, my 18 students and I generated almost 500 tweets.

Thesis Formation

Twitter’s character limit enabled my students to practice making clear, concise claims. Though Twitter now permits tweets of 280 characters, at the time of my course (Fall 2016), tweets were capped at 140 characters (Larson 2017). As Mark Sample and Peter DePietro have written, this limit urges students to condense and focus their ideas (Sample 2010; DePietro 2013, 73, 76).

During the week in which they watched and live-tweeted La Bohème, my students were also brainstorming for their first paper. In WR 100, the first paper focuses on thesis statements and central claims.[3] For this assignment, I asked the students to argue whether a particular course text (either George Du Maurier’s 1894 novel Trilby or La Bohème) was truly “bohemian.” They needed to agree or disagree (or, ideally, find some kind of middle ground) with literary critic Jonathan Freedman’s claim that bohemia is “thoroughly benign: while poverty, prostitution, and drunkenness are hinted at…characters remain untainted by its worst aspects” (Freedman 2000, 98-9).

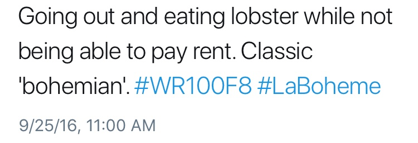

Live-tweeting, as it turned out, was not entirely auxiliary to my students’ work on their first paper, as it enabled them to practice making concise, authoritative arguments. One student, for example, tweeted about his perception of the hypocrisies and contradictions of bohemia (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: This image depicts a screenshot of a student’s tweet, which reads, “Going out and eating lobster while not being able to pay rent. Classic ‘bohemian.’ #WR100F8 #LaBoheme.”

This student’s tweet, though casual and humorously snarky, informed the argument of his first paper. In this student’s early drafts, the thesis was vague, wordy, and unclear, so I pointed him back to this tweet as an example of a sharp statement that captured his attitudes about a course text. In a one-on-one meeting, I asked the student to explain what he meant by his Twitter comment “Classic ‘bohemian.’” He emphasized that the bohemians are often hypocritical in that they pretend not to have money but at the same time spend it with abandon. I pointed out that his tweet represented a much clearer and more direct argument than his original paper. In the student’s final draft, he agreed with Freedman’s notion of “bohemian gaiety” but also furthered the conversation by discussing the class dynamics at work in bohemian literature – an idea sparked by the live-tweeting exercise.

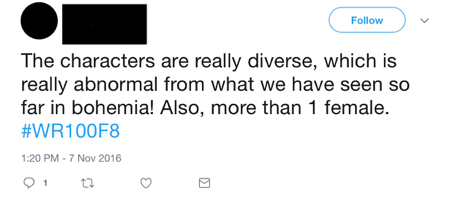

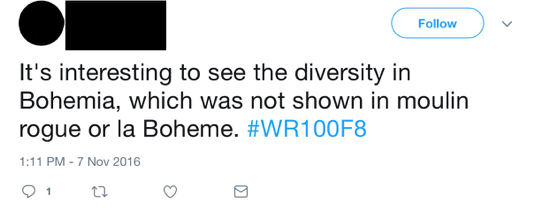

Several students began to develop ideas for their final papers while live-tweeting Rent. Throughout the semester, several students had become frustrated with the whiteness of Bohemia, as evidenced by the racially homogenous groups of characters in La Bohème, Trilby, and even Lena Dunham’s TV series Girls. My students were thus eager to discover– and discuss– the racial and ethnic diversity in Columbus’s Rent. Their tweets (Figs. 5 and 6) can be read as mini-thesis statements that make arguments about Rent and compare it to our other course texts.

Figure 5: This image depicts a screenshot of a student’s tweet, which reads, “The characters are really diverse, which is really abnormal from what we have seen so far in bohemia! Also, more than 1 female. #WR100F8.”

Figure 6: This image depicts a screenshot of a student’s tweet, which reads, “It’s interesting to see the diversity in Bohemia, which was not shown in moulin rouge or la Boheme. #WR100F8.”

In both cases, these tweets later transformed into formal thesis statements. One student’s final claim read, “[Larson] shows a diverse array of characters, along with the struggles that these characters face, and the close-knit communities that help them thrive…By portraying diverse characters and their struggles, close-knit communities, and artistic lifestyles, Larson makes Rent a bohemian text.”

While first-year writing students often struggle to eliminate “wordiness,” develop their own voices, and articulate forceful claims, in these moments, Twitter enabled my students to articulate short, incisive, and commanding arguments about the material. By mandating that tweets be less than 140 characters, Twitter encouraged my students to remove unnecessary jargon, hone in on their main ideas, and share their points of view.

Evidence Incorporation

As composition instructors have long discussed, it is often difficult to teach first-year writing students how to find and incorporate evidence.[4] In my experience, students often struggle to come up with concrete examples or are hesitant to quote or incorporate specific words, lines, or images from a text. They face an even greater challenge weaving these examples into an unfolding thesis. However, I found that the live-tweeting exercise helped my students practice these skills. The immediacy of live-tweeting compelled my students to pay close attention to specific moments as they occurred. Moreover, the technology that allowed them to pause videos, screenshot images, and quote individual lines helped them to engage more closely and carefully with specific moments and ponder how they served as evidence of larger points or ideas.

One student, for instance, live-tweeted about a specific image in Larson’s Rent (Fig. 7). In order to do so, the student had to pause the video, screenshot the image, and attach it to the tweet. This act allowed the student to examine and interpret the shot. In the text of the tweet, the student narratively connects the image to a larger point about Rent’s depiction of the discrimination faced by the LGBTQ characters in the film. Here, live-tweeting helped the student engage with evidence in a way she might not have were she passively viewing the film for homework.

Figure 7: This image depicts a screenshot of a student’s tweet, which reads “There is rampant hatred and opposition to the group. Words like ‘Nasty’ and ‘Bomb’ deface this beacon of hope. #WR100F8.” The tweet also includes an image from the film Rent, of a blue sign outside the Ryder Community Center, which reads “Helping to build a stronger community,” but is defaced with graffiti.

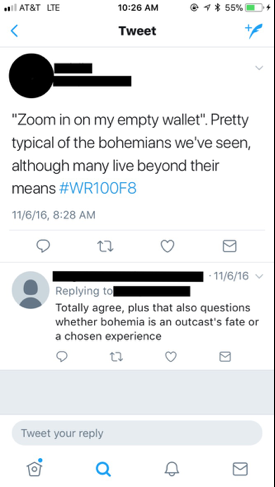

Similarly, in Figure 8, a student quotes a line from Rent and analyzes it in the context of broader discussions about the class dynamics in bohemian works. The student who replies also raises another question in response to the quotation, building a dialogue around a piece of evidence.

Figure 8: This image depicts a screenshot of a student’s tweet, which reads, “Zoom in on my empty wallet”. Pretty typical of the bohemians we’ve seen, although many live beyond their means #WR100F8.” The image also pictures another student’s response to this tweet, which reads, “Totally agree, plus that also questions whether bohemia is an outcast’s fate or a chosen experience.”

In these instances, live-tweeting allowed my students to practice evidence incorporation and interpretation and to work together to make meaning out of textual moments.

Peer Review

Live-tweeting also propelled my students to practice what most instructors view as a crucial part of the writing process: peer review, or what BU’s Writing Program refers to as “respond[ing] productively to the writing of others” (“WR 100 Syllabus Template,” 2014). Kate Turabian insists that first-year writers must learn not only to make their own arguments but also to “[a]cknowledge and respond to readers’ points of view” (Turabian 2010, 68).

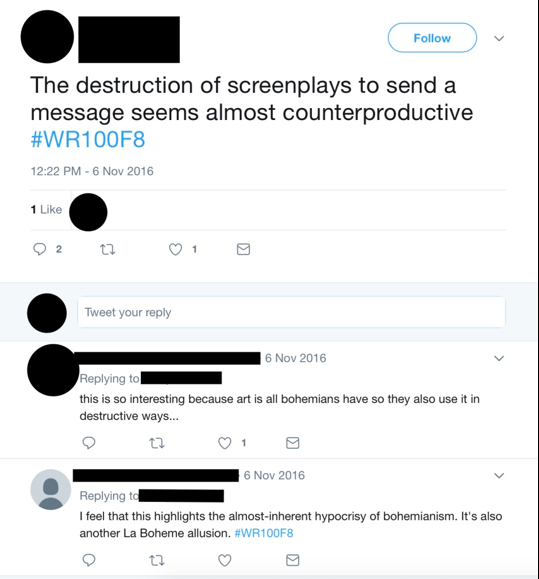

By responding to each other’s live-tweets about course texts, my students could bounce ideas off each other. Though they did so in a casual, conversational manner, they were nonetheless entering the kinds of critical conversations Turabian describes (Turabian 2010, 63-4).[5] Not only did my students offer each other implicit affirmation in the form of “likes” and “retweets” but they also replied directly to each other’s comments, challenging their classmates and urging them to think through how their claims relate to broader questions about bohemianism and art culture. In Figure 9, for instance, one student comments on the scene in Rent in which Mark and Roger burn screenplays to stay warm and articulates that it seems “counterproductive” to bohemians’ alleged venerations of art:

Figure 9: This image depicts a student’s tweet, which reads, “The destruction of screenplays to send a message seems almost counterproductive #WR100F8.” The image shows that the tweet received “1 Like.” The image also includes two students’ responses. The first reads, “this is so interesting because art is all the bohemians have so they also use it in destructive ways…” The second reads, “I feel that this highlights the almost-inherent hypocrisy of bohemianism. It’s also another La Boheme allusion.”

The respondents not only affirm their peers’ point (“this is so interesting”) but also build shared insights about the scene’s portrayal of the destructiveness and hypocrisy of bohemia. In doing so, they practice the kinds of acknowledgment and response Turabian describes.

Live-tweeting also served as a tool for peer review when students live-tweeted each other’s final presentations. Some students gave their peers positive reinforcement (Fig. 10), sometimes in the form of humorous GIFs (Fig. 11).

![Figure 10: This image depicts a student’s tweet, which reads, “#WR100F8 I think that [STUDENT NAME REDACTED] has a great lens for arguing against Rent’s bohemianism. This financial outlook should be a great paper.” The image also reveals that this tweet has received “2 Retweets” and “2 Likes.”](https://jitp.commons.gc.cuny.edu/wp-content/blogs.dir/614/files/2018/05/Fig10.png)

Figure 10: This image depicts a student’s tweet, which reads, “#WR100F8 I think that [STUDENT NAME REDACTED] has a great lens for arguing against Rent’s bohemianism. This financial outlook should be a great paper.” The image also reveals that this tweet has received “2 Retweets” and “2 Likes.”

![Figure 11: This image depicts a student’s tweet to another student, which reads, “@[STUDENT NAME REDACTED] argues that counterculture is sold to a mainstream audience, which is not an accurate portrayal of Bohemia #wr100f8.” The tweet is accompanied by a GIF, which depicts a white man standing at a podium with a gavel. The GIF includes the text “SOLD!”](https://jitp.commons.gc.cuny.edu/wp-content/blogs.dir/614/files/2018/05/Fil11.png)

Figure 11: This image depicts a student’s tweet to another student, which reads, “@[STUDENT NAME REDACTED] argues that counterculture is sold to a mainstream audience, which is not an accurate portrayal of Bohemia #wr100f8.” The tweet is accompanied by a GIF, which depicts a white man standing at a podium with a gavel. The GIF includes the text “SOLD!”

![Figure 12: This image depicts a student’s tweet to another student, which reads, “@[STUDENT NAME REDACTED] are you focusing only on the pilot episode of girls or are you also analyzing later episodes in your paper? #WR100f8.” The image shows that this tweet has received “1 Like.”](https://jitp.commons.gc.cuny.edu/wp-content/blogs.dir/614/files/2018/05/Fig12.png)

Figure 12: This image depicts a student’s tweet to another student, which reads, “@[STUDENT NAME REDACTED] are you focusing only on the pilot episode of girls or are you also analyzing later episodes in your paper? #WR100f8.” The image shows that this tweet has received “1 Like.”

![Figure 13: This image depicts a student’s tweet to another student, which reads, “@[STUDENT NAME READCTED] What do you mean by Mark is forced into the corporate world style? He never dresses in a suit in those scenes #wr100f8.” The tweet includes an image from the film Rent, which depicts the character Mark riding his bike down a New York City street. He has red hair and glasses and is wearing a tan jacket and carrying a messenger bag. The image includes the text, “How do you document real life when real life’s getting more like fiction each day?”](https://jitp.commons.gc.cuny.edu/wp-content/blogs.dir/614/files/2018/05/Fig13.png)

Figure 13: This image depicts a student’s tweet to another student, which reads, “@[STUDENT NAME READCTED] What do you mean by Mark is forced into the corporate world style? He never dresses in a suit in those scenes #wr100f8.” The tweet includes an image from the film Rent, which depicts the character Mark riding his bike down a New York City street. He has red hair and glasses and is wearing a tan jacket and carrying a messenger bag. The image includes the text, “How do you document real life when real life’s getting more like fiction each day?”

Live-tweeting encouraged my students to help each other with their work and to engage in the scholarly practices of listening and responding to each other’s arguments. My students practiced in real time the critical conversations they needed to develop in their formal papers.

Conclusion

Live-tweeting represented a surprisingly valuable tool that helped students practice, in a more informal setting, some of the skills they would develop further in their longer papers: making strong claims, locating and analyzing textual evidence, and engaging in critical conversations with other scholars. While instructors often view Twitter and other social media platforms as frivolous distractions or frustrating inhibitions to classroom learning, the experience of using Twitter in WR 100 reminded me that, at least in the composition classroom, we can look to such technologies for strategies and approaches that resonate, rather than clash, with our course aims. In some cases, I realized, perhaps all it takes to spark a claim, ponder a piece of evidence, or converse with a peer is 140 characters.

Notes

[1] For more information on the Boston University College of Arts and Sciences Writing Program, please see <http://www.bu.edu/writingprogram>.

[2] Townsend directed students to create separate Twitter accounts for her course, though she did allow them to share their projects publicly. I offered students the choice of whether to use their own accounts or to create new ones because several students expressed an interest in sharing their live-tweets with friends and family who already “followed” their accounts.

[3] The first paper asks students to create what Kate Turabian in Student’s Guide to Writing College Papers (the text used in the BU Writing Program) calls a “main claim” or the “core” of an argument (Turabian 2010, 65-6).

[4] See, for example, James Slevin, “Letter to Maggie” (Slevin 1999, 3).

[5] In fact, Turabian urges students to “[b]ounce ideas off friends rather than sources” and use their classmates to practice acknowledgement and response strategies (Turabian 2010, 38-9).

Bibliography

Boston University College of Arts and Sciences Writing Program. 2014. “WR 100 Syllabus Template, Version 2014-07-1.” Course Syllabus. Boston University, Boston, MA, <www.bu.edu/wpnet/files/2014/07/Fall-2014-WR-100-Syllabus-Template.doc>

Croxall, Brian. 2010. “Reflections on Teaching with Social Media.” The Chronicle of Higher Education: Profhacker. June 7, 2010.

<https://www.chronicle.com/blogs/profhacker/reflections-on-teaching-with-social-media/24556>.

DePietro, Peter. 2013. “Microblogging in the Classroom.” Counterpoints 435, no. 1: 73-83.

Freedman, Jonathan. 2000. The Temple of Culture: Assimilation and Anti-Semitism in Literary Anglo-America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Greenhow, Christine and Benjamin Gleason. 2012. “Twitteracy: Tweeting as a New Literacy Practice.” The Educational Forum 76, no. 4 (October): 464-478.

Hawkins, Tracy L. 2015. “‘Can You Tweet That?’ Twitter in the Classroom.” Feminist Teacher 25, no. 2-3: 153-168.

Hunco, R., G. Heiberger, and E. Loken. 2011. “The Effect of Twitter on College Student Engagement and Grades.” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 27, no. 2 (April): 119-132.

Hunter, Jevon D. and Heidie Jean Caraway. 2014. “Urban Youth Use Twitter to Transform Learning and Engagement.” The English Journal 103, no. 4 (March): 76-82.

Jacquemin, Stephen J, Lisa K. Smelser, and Melody J. Bernot. 2014. “Twitter in the Higher Education Classroom: A Student and Faculty Assessment of Use and Perception.” Journal of College Science Teaching 43:6 (July/August): 22-27.

Koh, Adeline. 2014. “Livetweeting Classes: Some Suggested Guidelines.” The Chronicle of Higher Education: Profhacker. January 28, 2014. <https://www.chronicle.com/blogs/profhacker/livetweeting-classes-some-suggested-guidelines/54963>

Larson, Selena. 2017. “Welcome to a world with 280-character tweets.” CNN Tech. November 7, <http://money.cnn.com/2017/11/07/technology/twitter-280-character-limit/index.html>.

Nicholson, Julie and Tomás Galguera. “Integrating New Literacies in Higher Education: A Self-Study of the Use of Twitter in an Education Course.” Teacher Education Quarterly 40, no. 3 (Summer 2013): 7-26.

Sample, Mark. 2010. “A Framework for Teaching with Twitter.” The Chronicle of Higher Education: Profhacker. August 16, 2010. <https://www.chronicle.com/blogs/profhacker/a-framework-for-teaching-with-twitter/26223>.

Slevin, James. 1999. “Letter to Maggie.” Sweetland: Gayle Morris Sweetland Writing Center 23 (March): 1-4.

Townsend, Sarah L. 2017. “Ulysses Here and Now: Using Twitter to Teach Experimental Literature.” Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy. February 1, 2017. <https://jitp.commons.gc.cuny.edu/ulysses-here-and-now-using-twitter-to-teach-experimental-literature/#_ednref4>

Turabian, Kate L. 2010. Student’s Guide to Writing College Papers. 4th ed. Eds. Gregory Colomb and Joseph Williams. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

'A Claim in 140 Characters: Live-Tweeting in the Composition Classroom' has 3 comments

January 15, 2019 @ 8:30 pm Jalen Thompson

Did students where the film on their phones or did they watch it on a projector in class? It was unclear to me how they were able to pause and take screenshots of the film. I am asking because I think this is something that could be really important to use in a film class.

January 7, 2019 @ 6:55 pm Possibly Impossible; Or, Teaching Undergraduates to Confront Digital and Archival Research Methodologies, Social Media Networking, and Potential Failure /

[…] Draucker, Shannon. 2018. “A Claim in 140 Characters: Live Tweeting in the Composition Classroom.” The Journal of Interactive Technology & Pedagogy, May 23, 2018. https://jitp.commons.gc.cuny.edu/a-claim-in-140-characters-live-tweeting-in-the-composition-classroo… […]

September 20, 2018 @ 2:41 pm Taylor Roust

I have been thinking of incorporating Twitter into my freshman composition course. Thanks for the good ideas about ways to use Twitter.