A New Twist on Page and Stage in Shakespeare Studies

Christy Desmet, Josiah Meigs Distinguished Teaching Professor, University of Georgia

Review of Macbeth, Read & Watch: Complete Text and Performance, by William Shakespeare, WordPlay™ Shakespeare (New York: New Book Press, 2013). $9.99.

Shakespearean eBooks designed for school use are multiplying daily. Some are just electronic transformations of print texts that can be consumed on Kindle, iPad, or computer, but other, more interactive packages include multimedia enhancements and other tools for reading and analyzing Shakespeare. A recent contribution to the interactive Shakespeare genre is a Macbeth produced by the WordPlay™ Shakespeare and educational technologist Alexander Parker, with Yale University’s David Scott Kastan serving as academic advisor. Priced at $9.99, the eBook is available for iPad and Mac.[1]

Promotional material for the WordPlay™ Shakespeare Macbeth claims that it offers “a new approach to reading, watching, understanding, and enjoying Shakespeare’s plays. Now, Half the Page is a Stage.” This claim is not empty hyperbole, for the statement that “half the page is a stage” describes literally the rhetorical arrangement governing this eBook. The text appears, just as it would in a physical paperback, on the left-hand page, while on the right a click of the button produces a dramatic enactment of the exact words printed on the facing page.

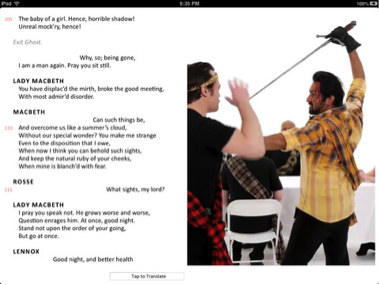

Screen shot of confrontation between Macbeth and the ghost of Banquo in 3.4, WordPlay™ Shakespeare Macbeth.

Screen shot of confrontation between Macbeth and the ghost of Banquo in 3.4, WordPlay™ Shakespeare Macbeth.

The performers, a small ensemble of New York actors, handle the language well, and Jessica Bauman’s direction is well-adapted to the iBook context. Costumes are simple – just basic, contemporary black cloth and leather with identifying pieces of tartan to distinguish the players from one another. Sets are spartan, almost nonexistent. The WordPlay™ Shakespeare Macbeth offers a modest array of study aids. Each page offers a plain-language “translation” of the text, available with a tap of the finger. Individual words are not glossed, although there is a search function that allows users to consult a rudimentary dictionary and various web dictionaries or Wikipedia. The reader can highlight portions of text and add notes that may then be collected as “Study Cards”–presumably in preparation for quizzes and tests–and shared through social media. Each scene is preceded by repeated character descriptions and an admirably clear Synopsis, keyed to visual snapshots of the forthcoming action.

To assess the advantages and shortcomings of the WordPlay™ Shakespeare, I would like to compare the application on specific points to its three closest competitors: the Folger Luminary Shakespeare, Shakesperience, and Shakespeare in Bits versions of the play.

Standout Features: Each application has its own defining virtues. The Folger Luminary Macbeth has copious expert commentary and allows readers to add texts to a “path” to make up their own performance texts, which may be used in either class or rehearsal. Shakespearience offers a wide array of still pictures and sound clips. Shakespeare in Bits pairs up a text with cartoon enactments, and the WordPlay™ Shakespeare Macbeth, of course, offers embedded dramatizations with actual actors.

Text: Here, both the Folger Luminary Shakespeare and Shakespearience are superior to the WordPlay™ Shakespeare Macbeth. The Folger app uses the New Folger Shakespeare texts, and Shakespearience uses the text edited by noted scholar David Bevington. The WordPlay™ Shakespeare Macbeth says that its text combines the First Folio with the 1866 Globe Macbeth, the latter presumably being chosen because it was in the public domain. For Macbeth, which derives solely from the First Folio version, this offers less of a problem than it might for a play with a more complicated textual history.[2] (Tellingly, the Shakespeare in Bits version, which is the app marketed most aggressively to a younger school crowd, offers no information about its choice of text.)

Pedagogical Extras: All of the applications offer the kinds of student support you might expect. Each gives readers the capacity for bookmarking and a space for taking notes. Folger Luminary and the WordPlay™ Shakespeare have the added advantage of letting students share these thoughts via social media. The usefulness of these tools, of course, depends entirely on the teacher and students.

Reading Support: Here, as well, the WordPlay™ Shakespeare Macbeth was less satisfactory than its immediate competitors. The Folger Luminary Macbeth offers no in-text glosses, but given its extensive paratext of expert scholarly opinion, this version is aimed clearly at university students and theater professionals, and the notes are first-rate. Shakesperience provides both 1-click definitions of difficult words and more extensive glossary entries and production notes. Shakespeare in Bits provides clear glosses of difficult words within the lines of texts where these words appear, so that it offers the most elegant digital alternative to marginal glosses in a print text. The WordPlay™ Shakespeare Macbeth, as noted above, offers a dictionary with some definitions in a pop-up window, but often sends the reader in search of definitions on the Web through a separate browser window outside the application. This slows down navigation and makes searching more of a hit-and-miss process. Instead of in-line glosses, the WordPlay™ Shakespeare Macbeth includes for each page a plain-language “translation” of the Shakespearean text. These vary in quality and helpfulness and, given the differing degrees to which Shakespearean language was translated into a contemporary idiom at different parts of the play, may be the product of different hands. Attending frequently to the plain-language translations, which calls up a pop-up text overlay, also slows down the reading process to an unacceptable degree.

Platform: Only Shakespeare in Bits is available for multiple devices (iPhone, iPad, and iPod Touch); there are as well desktop versions for both PC and Mac. The Folger Luminary Shakespeare and Shakesperience are both designed for the iPad only. As noted above, the WordPlay™ Shakespeare Macbeth may be used only on an iPad or Mac computer. The requirement for an Apple brand tablet, in particular, is a negative, but consistent with the limitations of its competitors. Such issues of access, however, will affect teachers’ ability or willingness to use the application the classroom.

Performance: This is where the WordPlay™ Shakespeare Macbeth really excels. The Folger Luminary Shakespeare has a complete audio podcast of the play produced by the Folger Theater, but the audio is a stand-alone feature, not integrated with the text. In effect, the user can read the play, framed or not by scholarly commentary, and hear the play, but not do both at once. The Shakesperience Macbeth offers an extensive gallery of still images from historically important productions and, more important, multiple audio clips embedded within the text for easy access and comparison between actors and productions. But here again, reading, seeing, and hearing the play are separate activities. Shakespeare in Bits pairs the printed text on the right-hand page with an animated cartoon on the left; the audio derives from the old Naxos Audiobook version of Macbeth. But while the cartoon does a good job of sketching in setting and character arrangements, it cannot convey adequately such features of human communication as facial expression, emotion, or gesture–cues that both live drama and its remediations depend on to communicate text to audiences by way of their eyes and ears. The WordPlay™ Shakespeare Macbeth, by contrast, offers not live drama, not even filmed drama, but a hybrid experience that is both expressive and communicative.

I would like to spend the remainder of this review exploring just what kind of hybrid experience the WordPlay™ Shakespeare Macbeth offers to users. The creators promote their product not as filmed drama, but as a reading experience. In the animated conceit underlying this Macbeth, “half the page is a stage,” actors often enter and exit at the fold between printed text and screen, so that the stage visually melts back into the page. The dominance of page over stage can be problematic because every recording stops precisely at the final word printed on the left-hand page. Usually, this is not a problem, but occasionally, interruptions of soliloquies and witchy incantations became annoying. As I grew more familiar with the app, however, I found myself becoming more skilled at swiping rapidly to execute “page” turns.

In some ways, the WordPlay™ Shakespeare simply updates the experience of watching the old BBC Shakespeare series with a printed scholarly text balanced on one’s lap. The faithfulness of both to the so-called “complete” text – with no cutting of actors, scenes, or lines – is particularly helpful in highlighting those scenes often pruned or eliminated in commercial films, such as Banquo’s colloquy with Fleance before they are attacked (2.1) or the Old Man’s conversation with Ross about nature’s omens (2.4). In the case of Macbeth, the urge toward inclusiveness provides a more rounded historical view on the play’s events. Perhaps more obviously, the mediated presence of human actors aids basic comprehension by supplementing spoken verse with action, gesture, and facial expressions. Best of all, I emerged from the “read and watch” experience knowing and even caring about the actors personating Macbeth, Lady Macbeth, Banquo, Macduff, and the rest. None of the other applications offered these important features of dramatic experience.

It is interesting to speculate about how this new format for “reading” Shakespeare changes our sense of performance as well as of text. To make the action literally fit on the digital page, the WordPlay™ Shakespeare Macbeth substitutes interactions between pairs and small groups of figures for larger-ensemble scenes. In this way, the dramatization is more like a workshop performance than full-scale theater. The prevalence of close head shots and direct address to the reader resembles generally the filmic strategy of televised performances of Shakespeare; the general absence of settings and props, coupled with the pared-down interactions between actors, gives the performance a modernist, Beckettian ethos. But still, the direct engagement with readers renders social (and even emotional) the act of reading printed text on screen.

To give a concrete example, in 1.5, when Lady Macbeth enters reading the letter in which Macbeth communicates his encounter of the weird sisters, in the WordPlay™ Shakespeare Macbeth Francesca Faridany faces the reader, with her eyes cast down to focus on the text, while reading Macbeth’s letter; but when she looks up to address Macbeth in absentia – “Glamis thou art, and Cawdor, and shalt be what thou art promised” – the reader’s face becomes the actress’s focal point, so that her apostrophe to the absent husband is simultaneously a direct address to the reader. Gestures toward the reader, extending through the fourth wall (if this were indeed a stage), solidify the bond. This is a quite intimate moment of theater.

Compare the same moment from the Shakespeare in Bits cartoon, which follows a puzzling new trend of associating Lady Macbeth with bathtubs. As Macbeth’s “dearest partner in greatness,” she reads the letter while seated, in profile, in the bath. When she begins musing about Macbeth’s nature, we get a close-up of her partial face–just the eye and lips, really, which suggests contemplation more than a moment of confiding in the reader. We are close to Lady Macbeth, but not in contact with her.

“Glamis thou art . . .”: Shakespeare in Bits Macbeth

The WordPlay™ Shakespeare Macbeth offers more contact with the dramatis personae than do even film and television versions that strive to communicate the ethos of live theater. For instance, in the television remake of Gregory Doran’s stage performance (film directed by John Casson, 1979), Judi Dench as Lady Macbeth turns to the camera as she begins musing aloud about the letter’s content, but true to the production’s theatrical origin, even as the camera pans in on her face, she fixes her eyes above and beyond the DVD viewer to lock eyes with an invisible theater audience, and so seems to be delivering a soliloquy of thought in process rather than a direct address.

The Rupert Goold Macbeth, also produced for television and DVD, draws on a broader array of filmic effects. Kate Fleetwood, as Lady Macbeth, is glimpsed through the cage bars of a descending elevator car from the back and in profile, with the camera going out of focus as she reads; Fleetwood faces the camera only when she begins the apostrophe to Macbeth – “Glamis thou art . . .” But in this case as well, Lady Macbeth’s gaze is diffuse and seems directed inward. We are voyeurs more than confidantes.

Kate Fleetwood in the Rupert Goold Macbeth

The WordPlay™ Shakespeare Macbeth, like other media through which we consume Shakespeare in the post-book, post-film age, is changing basic concepts such as page and stage, reading and watching. And this, I think, is an exciting development. While students and teachers of all ages might lament the relative lack of scholarly apparatus, I found instead that the active experience of reading, watching, and listening to Shakespeare all at once was invigorating and useful, as likely or more likely to produce understanding of Shakespeare’s play than other, more familiar media versions and textual apparatus. If you or your students use the WordPlay™ Shakespeare Macbeth, don’t worry about the textual translations, definitions, or note cards. Just read and watch, moving from page to page as expeditiously as possible. You will enjoy a new, pleasurable, and profitable kind of Shakespearean engagement.

Bibliography

Macbeth. 2010. Dir. Rupert Goold, perf. Patrick Stewart, Kate Fleetwood. Great Performances. U.S. PBS Broadcasting. OCLC 669851626.

Macbeth. 1979. Dir. Trevor Nunn, TV film directed by John Casson, perf. Ian McKellen, Judi Dench. U.K. Thames Television. OCLC 310081955.

Shakespeare, William. 2013. Macbeth, based on the New Folger Shakespeare Editions. Created for iPad by Elliott Visconsi and Katherine Rowe, eds. Barbara Mowat and Paul Werstine. Dir. Katherine Rowe. Luminary Digital Media. iPad Application. Luminary Digital Media.

Shakespeare, William. 2012. Macbeth. Eds. Dominique Raccah and Marie Macaisa. Shakesperience. New York: Sourcebooks, Inc.

Shakespeare, William. 2011. Macbeth. Shakespeare in Bits. Mindconnex.com.

[1]Hamlet, for instance, was printed in three early versions (the first quarto of 1603, the second quarto of 1605, and the first folio of 1623); most contemporary texts at least acknowledge their differences, and many scholarly editions now include all three texts of Hamlet. A text put together from the first folio and the 1866 Globe edition would be seriously out of step with accepted editorial practice.

[2] Technical requirements, according to the iBookstore: “To view this book, you must have an iPad with iBooks 3 or later and iOS 5.1 or later, or a Mac with iBooks 1.0 or later and OS X 10.9 or later.”

About the Author

Christy Desmet is Josiah Meigs Distinguished Teaching Professor at the University of Georgia. She works on multimodal rhetoric, pedagogy of electronic portfolios, and Shakespeare and media. With Sujata Iyengar, she is co-founder and co-editor of the online multimedia journal,Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation.

'A New Twist on Page and Stage in Shakespeare Studies' has 3 comments

June 23, 2022 @ 12:48 am John

Nice info more info check https://heedhealtheducation.com.au

April 26, 2022 @ 5:49 am https://www.fireball20xl.com/

Pretty! This was a really wonderful post. Thank you for providing this information.

July 18, 2014 @ 7:09 pm The Shakesperience etc. | Scribblings

[…] because otherwise, all my reservations about enhancements would come back in full force.) Now, this article nicely compares the merits of several enhanced editions of Shakespeare, such as the Folger […]