Overview

Virtual Worlds, a second-year undergraduate digital humanities (DH) course at the University of Toronto, is built around experiential learning in labs, libraries, makerspaces, and museums. In Winter 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic closed all these spaces, and our course moved entirely online. To compensate, Alexandra Bolintineanu, the course instructor, developed a new learning module. After the instructor’s invitation to Komal Noor, library user experience consultant, to lead a usability workshop for the class, students conducted a usability study of our webinar platform, BB Collaborate, and examined their experience in light of critical digital justice scholarship. This paper analyzes our experience as instructor (Bolintineanu), library user experience consultant (Noor), and students (Ayow, Carino, and McDonald) in the framework of inquiry-based learning.

Background

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the course Virtual Worlds was anything but virtual. Virtual Worlds is a second-year undergraduate introduction to spatial digital humanities (DH). The course encompasses topics like digital mapping, augmented and virtual reality, and 3D printing. In ordinary times, students learned about course topics experientially. Under library and museum specialists’ guidance, we visited the University of Toronto’s Map and Data Library lab to build digital maps; we used the MADlab, a library makerspace, to 3D print our own artifacts; we travelled to the Art Gallery of Ontario to examine museum artifacts both in their glass cases and in virtual reality renditions. The course was deliberately built around experiential and inquiry-based learning. This is a pedagogical approach in which students learn by making and doing, by actively applying the methods and inhabiting the workspaces of their discipline’s practitioners in order to discover or construct new knowledge (Pedaste et al. 2015). Across higher education, inquiry-based learning (IBL) functions as an adaptable pedagogical framework to strengthen research and interpretive skills, whether in the humanities and arts (Manarin 2016; Costes-Onishi et al. 2020), social sciences, or sciences (Pedaste et al. 2015).

This experiential, inquiry-based approach is central to teaching and learning in DH—so much so that, in an early international overview on the transmission of expertise within DH research centres, Lewis et al. memorably cite a practitioner who describes learning through “sessions where we bang our heads against the wall but eventually work through it” (Lewis et al. 2015). In DH classrooms, IBL takes many forms. It includes the building of digital tools and artifacts (Nowviskie 2016; Ramsay and Rockwell 2012); building digital exhibits around the collections of galleries, libraries, archives, and museums (McClurken 2011; Schlitz and Bodine 2012; Gold 2012; Liberman Cuenca and Kowaleski 2018; Buurma and Levine 2016; Faull and Jakacki 2015); and utilizing library makerspaces (Miller et al. 2018).

In keeping with this experiential learning philosophy, the course Virtual Worlds was built around inquiry-based learning opportunities in libraries, makerspaces, and museums. But in the school year of 2020–2021, libraries, makerspaces, and museums in Toronto closed because of COVID-19. Our experiential learning opportunities vanished. Our classroom shrank down to our computer screens. In response, Bolintineanu, the course instructor, developed a new module to encourage students’ experiential learning under pandemic restrictions. Specifically, Bolintineanu designed an assignment that invited students to examine their own lived experience as virtual learners by conducting a usability study of BB Collaborate, our webinar platform.

The module draws on Miriam Posner’s digital storytelling assignment for her Systems & Infrastructures course (Winter 2018, UCLA Information Studies). Posner’s assignment invites students to consider the significance of an infrastructural system within Susan Leigh Star’s theoretical approach to infrastructure:

Your framing question, borrowed from Susan Leigh Star’s “Ethnography of Infrastructure,” is: “What values and ethical principles do we inscribe in the inner depths of the built information environment?” That is, what can the history, configuration, and architecture of your piece of infrastructure tell us about the society that built it? (Posner 2018)

Susan Leigh Star’s framing question also informs the current assignment. Our project invites students to study our webinar platform, BB Collaborate. In addition to usability testing the platform, students also examine their lived experience of learning in that platform through the lens of critical digital justice scholarship (Noble 2018). That is, students consider not only how the platform works, but “what values and ethical principles … we inscribe in the inner depths of the built information environment” (Star 1999, 379). Alongside the experiential learning of conducting the usability study, scaffolded reflections serve to activate students’ metacognition and information literacy skills (Denke et al. 2020).

Before the Workshop: Preparatory Reading & Learning

At the beginning of the module, students become familiar with scholarship in critical digital studies, examining how tools, platforms, and algorithms are cultural artifacts inscribed with the values, power dynamics, and biases of their creators and users. To this end, students read, view, and discuss scholarship by Safiya Umoja Noble (2018) and Joy Buolamwini (2021), which examine how racist biases are embedded and amplified by Google Search (Noble) and facial recognition algorithms and platforms (Buolamwini).

This theoretical approach is then anchored in a hands-on workshop. Library user experience specialist Komal Noor introduced students to the field of user experience and usability testing (Noor 2021; Bolintineanu and Noor 2021). After the workshop, students conduct a mini usability testing session on their own webinar platform, BB Collaborate.

During the Workshop: BB Collaborate from Student & Instructor Perspectives

During the usability workshop, students take the role of user experience experts. As such, they interrogate both the student experience and the instructor experience of BB Collaborate.

Student view

For the student experience, students drew on their own background throughout the course, comparing the interface and affordances of BB Collaborate to their past in-class learning. Students also participated in a new, unrecorded session of BB Collaborate, so they could play with more options not available in regular classes. For example, what happened when the instructor engaged “no swearing” mode? Understandably, students were reluctant to test this mode by using swearwords in a chat with their professor. So Bolintineanu, the course instructor, engaged “no swearing” mode and typed swearwords into the class chat; students watched the words appear as a series of asterisks. After that, there was no stopping students—everyone wanted the chance to “misbehave” in class and test the limits of the no-swearing mode. This practice provided tension-relieving fun, but it also encouraged students to consider instructor-student power dynamics in virtual and physical classrooms.

Instructor view

For the instructor experience of the webinar platform, students first watched a video of their course instructor using (and misusing) BB Collaborate.

In this video I’m going to demonstrate some basic BB Collaborate tasks from the instructor’s perspective:

Setting up a BB Collaborate session

Sharing a website

Sharing a set of slides

1. To set up a BB Collaborate session, I navigate to BB Collaborate from within our Quercus site. I select “create session.” Then I configure the settings.

a. Enabling Guest Access allows us to share our lecture with people from outside our classroom, such as guest lecturers. I can give guests powers, such as (in the Presenter role) the ability to share their screen.

b. I set the session time and whether we can access the session before class

c. I decide if students are stuck with just listening to lecture and using chat; if they can have Presenter powers and share their own screen; and if they can write on the whiteboard. (I leave these options checked to keep our classes interactive.)

d. I always have to remember to disable access by telephone to make sure students don’t access the session by telephone and don’t get hit with surprise long-distance charges on their phone bill

e. If I’m feeling very proper and polite that day, I can even turn on the profanity filter, so if anyone types the f-word into chat, it’ll get blanked out

f. Once I’ve set up the session, I have to save it and close it in order to be able to get in.

2. Within the session, I can turn on my mic and webcam, so you can hear my voice and see my face. I can also see what you say within chat and respond—by voice or by typing. And (in Chrome, but NOT in Firefox) I can share content.

a. I can share a website. To navigate, I have to be on the website and I am not able to see the course chat. (I can hear pings when you say things; but I have to leave my website and return to BB Collaborate to see what you’ve said. With more than one tab open, it gets tricky fast.)

b. I can share slides. One way is by uploading slides to BB Collaborate. When I do so, I can advance slides from inside BB Collaborate, and I can see the chat and control my slides at the same time. But BB Collaborate often messes up the graphic formatting of my slides.

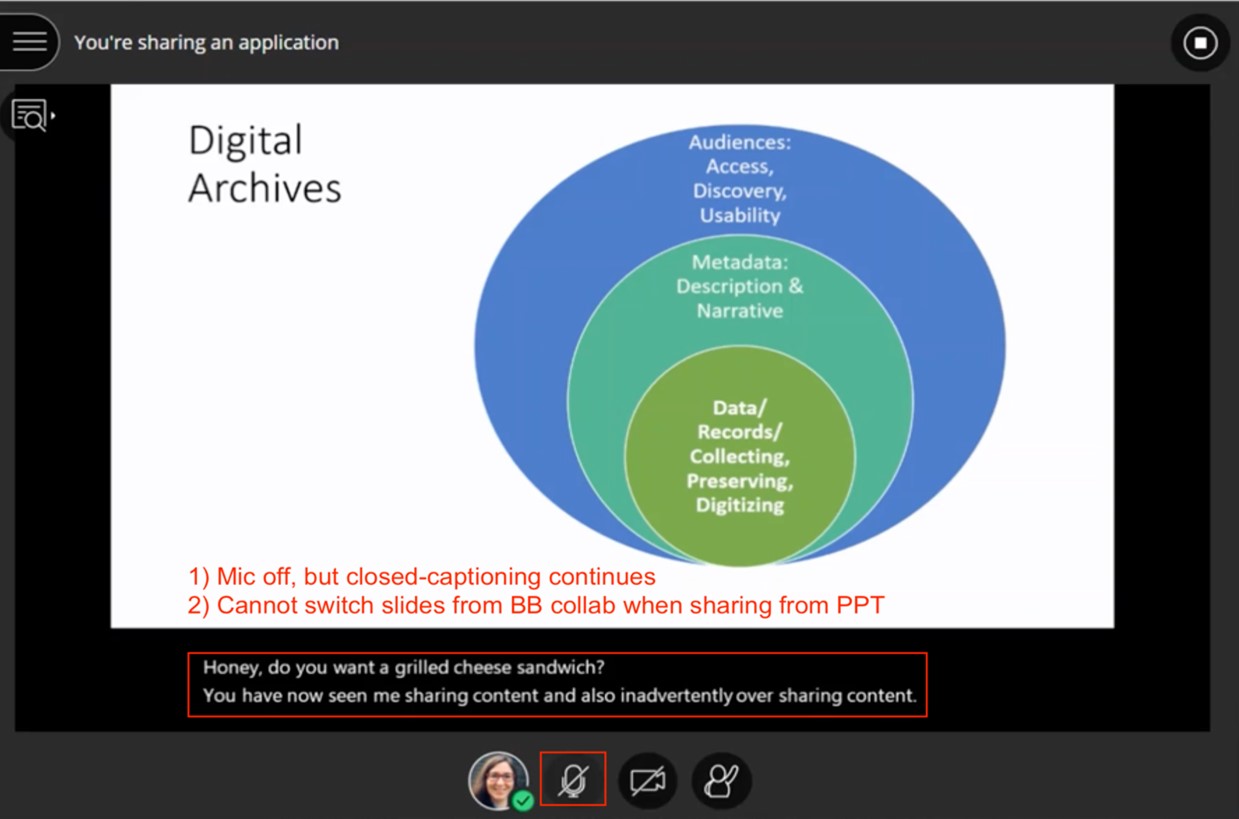

c. Another way to share slides is share my powerpoint window. When I do so, there are advantages and disadvantages. Disadvantage: I can NOT advance slides from inside BB Collaborate, and I can NOT see the chat and control my slides at the same time. Advantage: my slide formatting stays intact, and more importantly, I can use powerpoint’s close captioning to provide automated close captioning of my lecture.

Finally, one feature I discovered here is what happens when I turn off my lecture microphone during break. Let’s pretend it’s break and I’m turning off my mic. Students can no longer hear my voice, but the close captioning continues. If I’m teaching from home, as we often have to do during this pandemic, you suddenly get more information about my family than you wanted to. “Honey, do you want a grilled cheese sandwich?” You’ve now seen me sharing content – and also inadvertently oversharing content.

Thanks for viewing the usability video, and see you in class!

And that’s all, folks!

With Komal Noor’s guidance, students asked questions of their instructor to uncover errors, difficulties, and glitches.

One such glitch appears at the interface of BB Collaborate and PowerPoint: The instructor is sharing a PowerPoint presentation with automated closed captioning in BB Collaborate. Then, during a simulated lecture break, the instructor turns off BB Collaborate’s microphone.

However, PowerPoint’s closed captioning keeps transcribing and displaying on BB Collaborate what is said ostensibly off-microphone in the instructor’s home. The close captions in Figure 2 reveal that the instructor’s Zoom-schooling elementary school child is having a grilled cheese sandwich.

We laughed at the sandwich, but we also discussed how the closed captioning “glitch” further blurs the line between public and private, between classroom space and home environment. One student, Emma McDonald, referred to this as “the iconic ‘grilled cheese sandwich’ moment,” and used it to illustrate how our virtual classroom makes it “hard to separate professional [from] personal life.” Likewise, another student, Robyn Jane Carino, commented:

Established by the nature of social distancing and online learning, the boundaries between home and work have become blurred. By not allowing its users to set virtual backgrounds to preserve their privacy and by [displaying captioning] that continues to transcribe speech even when a user is muted, such BB Collaborate affordances further exacerbate these issues of boundaries and privacy.

After the Workshop: Critical Digital Media Analysis

After the workshop, students draw on their readings, their own lived experience as learners, and their workshop notes to compare in-person with webinar-based learning. As they close-read the platform, students consider ways to improve BB Collaborate and its user experiences. At the same time, they also examine how this platform reflects cultural understandings of how knowledge is transmitted, how learning happens, and how power lives in the classroom. Students do so through a scaffolded, guided reflection, a practice effective in inquiry-based learning to activate students’ metacognition and information literacy skills (Denke et al. 2020). For example, students observe that by controlling session settings, instructors have the power to limit who is able to share their camera feed, their voice, or their screen; to censor swearing in the classroom; and to make material available more freely or more restrictedly. As Robyn Jane Carino observes:

[The instructor’s control over session settings] speaks to the power dynamics between the two roles that have been preserved from live classrooms as instructors have the ability to shape the collective virtual learning experience of the class. Will students get to work together on this material? Will I be accessible and turn on closed captioning, as well as record my sessions for students who aren’t able to attend our live sessions? Will I enable my students to swear in class today? Will I allow them to speak to one another privately or can they only speak to a moderator in a private chat? Such questions shape the online learning experiences of the entire class, granting instructors a greater amount of power in comparison to students and affirming their superiority as the leader within the online class setting.

Similarly, Emma McDonald references user roles in BB Collaborate to analyze how the platform reflects power dynamics in undergraduate university classrooms:

In addressing the specific dynamics of institutional hegemony reflected in the user experience of BB Collaborate, we can look at the very fact of there being a distinction between instructor and student mode. That there are different capabilities for either role reinforces the differences in those roles. Specifically, it’s striking how much the instructor can restrict the expression of students in the BB Collaborate classroom. Being able to enable/disable private chat between students, choose whether or not they can share their content class wide and filter their language with a “profanity filter” are all features that reflect the way instructors are given significant control over how/when/to whom their students express themselves in a classroom setting. This control of expression reinforces the idea that in a student-instructor relationship, the instructor holds empirical knowledge and the student has to curb their expression to that instructor’s expectations.

During a webinar session, Jennifer Ayow analyzes the assumptions that may underlie BB Collaborate’s classification of the types of content instructors can share:

Once the instructor enters the session, they can choose which content to share. BB Collaborate categorizes content as “primary content,” “secondary content,” and “interact.” “Primary content” refers to a blank whiteboard, other application or window, camera, and files. Polls are the only type of “secondary content,” and breakout groups are listed under “interact.” Separating primary and secondary content from interact implies that the instructor is not interacting with students when sharing their slides, whiteboard, or other primary/secondary content. This understanding of teaching reflects a traditional lecture-style class where the professor talks “at” the students with minimal student participation. This is further reinforced by the fact that the chat is not visible when content is shared from another webpage or application—this design assumes that instructors will only talk to students about the application or webpage without listening to their feedback.

Finally, students also discuss how, on a learning platform supposedly accessible “anytime, anywhere” (Alhadreti 2020), social and financial inequalities between students translate into access inequalities. As Emma McDonald notes:

For the purpose of this class, students can’t access BB Collaborate without first paying tuition at [University] of [Toronto]. The platform’s existence behind the increasingly restrictive paywall of postsecondary education in Canada reflects the classist privatization of knowledge and qualification that exist in in-person teaching. To even be able to conduct this examination of how this software perpetuates and recreates existing university structures, I’ve had to accept those structures enough to participate in them. Having the ability to participate places me in a position of privilege that might undermine my criticisms. A perspective missing from both BB Collaborate and from this analysis is that of the people who can’t afford to be here; can’t afford to benefit from the exchange of knowledge on this platform, however imperfect.

Conclusions

The usability module introduced students to usability as a field, reinforced course readings in critical digitality, strengthened metacognition through experiential learning about learning, and invited students to discuss that isolating lived experience of pandemic learning within the classroom community. In an anonymous course evaluation, one student noted:

I appreciated that guest lectures were brought in this semester as we could not do the field trips that would regularly be planned. … I also appreciated the emphasis of practical uses of tools and the applicability of skills to future workplaces. It is reassuring to learn something grounded within all of the vast world of theory that is university. The assignments all enabled me to show and practice the skills I had learnt.

Using the principles of compassionate computing, the module took into account “the actual needs and limits of the users” (Pomputius 2020, 399): increases in anxiety and workload perception in online learning (Thomai and Michalopoulou 2022). Instead of introducing a new digital platform, we invited students to learn where they were already learning and gain a new perspective on an already familiar piece of technology. In the future, even after the pandemic, the course would continue to offer this module because it provides an opportunity for virtual inquiry-based learning to students whose campus access may be limited by health issues, caregiving responsibilities, or other obligations. If we learned anything when classrooms shrank down to the size of our computer screens, it is the obligation to widen access to learning for those who come after us.