In calculating the addenda of bills she frequently had recourse to digital aid.

—James Joyce, Ulysses (17.681–82), describing Molly Bloom[2]

The growth of the Digital Humanities has been fertilized by widespread training institutes, workshops, and certifications of technical skills. As we have developed those skills and methods, we DHers have also cultivated a corresponding skepticism about their value. Katie Rawson and Trevor Muñoz, for example, write that humanists’ suspicions of data cleaning “are suspicions that researchers are not recognizing or reckoning with the framing orders to which they are subscribing as they make and manipulate their data” (Rawson and Muñoz 2019, 280–81). Similarly and more broadly, Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren Klein describe in Data Feminism the need for high-level critique when our data does not fit predetermined categories—to move beyond questioning the categories to question “the system of classification itself” (D’Ignazio and Klein 2020, 105). When we have “recourse to digital aid,” to reappropriate Joyce’s phrase from the epigraph above, we break fluid, continuous (analog) information into discrete units. In the process, we gain computational tractability. What do we lose? What do we lose, especially, when we use digital tools in humanistic teaching, where we value the cultivation of fluidity and complexity? These recent critiques build on foundational work such as Johanna Drucker’s earlier indictment of the methods of quantitative DH:

Positivistic, strictly quantitative, mechanistic, reductive and literal, these visualization and processing techniques preclude humanistic methods from their operations because of the very assumptions on which they are designed: that objects of knowledge can be understood as self-identical, self-evident, ahistorical, and autonomous. (Drucker 2012, 86)

The problems that Drucker identifies echo the distinction that constitutes the category of the digital itself: whereas analog information exists on a continuous spectrum, digital data becomes computationally tractable by creating discrete units that are ultimately binary. Tractability can require a loss of complexity. One of Drucker’s examples involves James Joyce’s Ulysses: she evokes the history of mapping the novel’s Dublin as a signature instance of the “grotesque distortion” that can occur when we use non-humanistic methods to transform the materials of imaginative works (Drucker 2012, 94). At their worst, such methods can operate like the budget of Bloom’s day in Ulysses, which is an accounting of a complex set of interactions that obscures at least as much as it reveals, mainly by sweeping messy expenditures into a catch-all category called “balance” (17.1476). Making the numbers add up can render complexity invisible.[3]

I agree with Drucker’s point, albeit with some discomfort, as I am also the faculty lead of a digital project that involves mapping Ulysses, albeit in a different way. In this essay, I take up the pre-digital and digital history of transforming information about Joyce’s novel into structured data. Then I consider the concrete application of those methods in Ashplant: Reading, Smashing, and Playing Ulysses, a website that shares the scholarship of my Grinnell College students. Working on the site has brought us into the history of numbering Ulysses, for better and for worse, and shown us how Ulysses specifically—more than most texts—resists and undermines the very processes that give digital projects their analytical power. In creating Ashplant, we have found that undergraduate research provides an especially generative environment for breaking down the “unproductive binary relation,” in Tara McPherson’s words, between theory and practice in the digital humanities (Macpherson 2018, 22).

Numbering Ulysses from The Little Review to the Database

Although created with twenty-first–century digital technologies, Ashplant takes part in a tradition that has built over the full century since the publication of Ulysses. Readers of Joyce’s text have long sought to discipline its complexity by creating reading aids structured like tabular data. That process begins with numbering: facing a novel that sometimes runs for many pages without a paragraph break, we readers have given ourselves a unique, identifying value for each line of the text. In database architecture, such a value is called—with unintentionally Joycean overtones—a primary key.[4] The primary key for Ulysses assigns the lines a value based on episode and line numbers. In its most conventional form, the line numbering is based on the Gabler edition of the novel. The episode-line key lets us point, for instance, to “Ineluctable modality of the visible”—the first line of the third episode—as 3.1.

Ulysses is unusual in having such a reliably fixed convention for a work of prose. Prose normally resists stable line numbering because its line breaks change in response to variations of typesetting that we do not normally read as meaningful; thus arises the variation among editions of Shakespeare’s plays in the line numbering of prose passages. The difficulty of reading Ulysses, however, creates a desire for reliably numbered reference points, for stable ground upon which communities of readers can gather. Such numbering imposes orderly hierarchy upon a text that implicitly and explicitly resists the concept and practices of orderly hierarchy. The early history of numbering the chapters and pages of Ulysses reveals our modern standardization—and by extension the structured data in Ashplant—as the product of a century-old conflict between printed versions of Ulysses and efforts of readers to retrofit the text into tractable data.

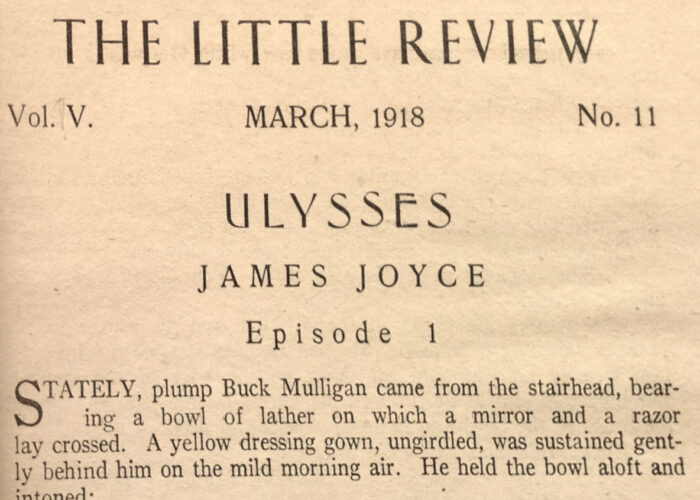

The serialization of Ulysses in The Little Review gave readers their first opportunity to grasp Joyce’s text with names and numbers. In the first issue containing part of Ulysses, the numbers begin: issue V.11, for March 1918. The Table of Contents reads, “Ulysses, 1.” The heading of the piece itself, on three lines, is “ULYSSES / JAMES JOYCE / Episode 1.”

The 1922 Shakespeare and Company edition removes the episode numbers of the Little Review installments and, indeed, removes most signposting numbers altogether. The volume has no table of contents. In the front matter, the sole indication of a section or chapter number is a page containing only the roman numeral I, placed a bit above and to the left of the center of the page.

This page is preceded by one blank page and followed by another, after which the main text of the novel begins, with no chapter title or episode number.

The page has no number, either. The following page is numbered 4, so the reader can infer that this is page three, and that the page with the roman numeral I has also been page one of the book. Episodes two and three are also unnumbered, so the reader can infer retrospectively that the roman numeral one indicated a section rather than a chapter or episode number. At this point, that is to say, the only stable numbering from The Little Review—the episode numbers—has disappeared entirely and been replaced by section numbers (just three for the whole book) that reveal their signification only gradually.

To fill the void of stable numbering, early readers of Ulysses relied on supplemental texts that have structured the naming and numbering conventions of the text ever since: the two schemata that Joyce hand-wrote for Carlo Linati and Stuart Gilbert in 1920 and 1921, respectively. The schemata have retained their power in part because of the tantalizing (apparent) simplicity of their form: they organize information about the novel in a structure closely resembling that of a spreadsheet or relational database table. Both schemata use the novel’s eighteen episodes as their records, or tuples—the rows that act essentially as entries in the database—and both populate each record with data corresponding to a series of columns largely but not entirely shared between the two schemata. The relational structure of the Linati schema, for example, has a record for the first episode that identifies it with the number “1,” the title “Telemachus,” and the hour of “8–9” (Ellmann 1972).

Today, any number of websites re-create the schemata by making the quasi-tabular structure fully tabular, as does the Wikipedia page for the Linati schema (“Linati Schema for Ulysses”).

Joyce’s sketches mimic tabular data so neatly that many later versions of the schemata put them in tabular structure without comment. The episode names and numbers again prove their utility: though the two schemata contain different columns, a digital version can join them by creating a single, larger table organized by episode.[5]

Organizing information by episode number has become standard practice in analog and digital supplements to Ulysses. In the analog tradition, readers have long used supplemental materials, organized episode by episode, to assist in the reading of the novel. An offline reader might prepare to read episode three, for instance, by reading a brief summary of the episode on Wikipedia, then consulting the schemata entries for the episode in Richard Ellmann’s Ulysses on the Liffey, then reading the longer summary in Harry Blamires’s New Bloomsday Book. In each case, that reader would look for materials associated with episode number three or the associated name “Proteus.” As much as any other work of literature, Ulysses invites that kind of hand-crafted algorithm for the reading process, all organized by the supplements’ adoption of conventional episode numbers and, often, the Gabler edition’s line numbers as well.

Digital projects, including Ashplant, rely on these episode and line numbers even more fundamentally. One section of Ashplant—the most conventional section—is called “Ulysses by episode.” It organizes and links to resources created by other writers and scholars, from classic nodes of reading Ulysses such as the Linati and Gilbert schemata to contemporary digital projects such as Boston College’s “Walking Ulysses” maps and the textual reproductions of the Modernist Versions Project.[6] This part of Ashplant, like those digital supplements to Ulysses and a long list of others, relies on the standard numerical organization: it has eighteen sections, corresponding to the eighteen episodes of the novel.

The underlying structure of these pages illustrates the importance of the episode number as a primary key: at the level of HTML markup, all eighteen pages point to the same file (“episode.php”) and therefore contain the same code.[7] The only change that happens when the user moves from the page about episode one to that for episode two, for example, is that the value of a single variable, “episode_number,” changes from “01” to “02.” Based on that variable, the page changes the information it displays, mainly by altering database calls that say, essentially, “Look at this database table and give me the information in the row where episode_number equals” the value of that variable. The database call looks like this, with emphasis added:

| /* Performing SQL query */ |

| $query = “SELECT a.episode_number, a.episode_name, b.episode_number, b.ls_time, b.ls_color, b.ls_people, b.ls_scienceart, b.ls_meaning, b.ls_technic, b.ls_organ, b.ls_symbols, b.gs_scene, b.gs_hour, b.gs_organ, b.gs_color, b.gs_symbol, b.gs_art, b.gs_technic |

| FROM episode_names a, schemata b |

| WHERE (a.episode_number=’$episode_number’) and (a.episode_number=b.episode_number)”; |

| $result = mysql_query($query) or die(“Query failed : ” . mysql_error()); |

| $num=mysql_numrows($result); |

The user’s input provides the value of episode_number (from 01 to 18) when the page loads.[8] Then, the page with this code queries the database to gather the information—the episode’s name, the schemata entries, and much more—from two database tables joined by the column containing that two-digit number in each table. The process gains its effectiveness from the conventionality of the episode numbers. The price of that efficacy is the loss of a good deal of information—from quirks of typesetting and handwriting, to alternative approaches to numbering the episodes, to the Italianate episode names from the schemata—that have at least as much textual authority as do our later simplifications.

Hierarchy and Classification

If there could be that which is contained in that which is felt there would be a chair where there are chairs and there would be no more denial about a clatter. A clatter is not a smell. All this is good.

—Gertrude Stein, Tender Buttons (Stein 2018, 53)

Line numbers, mainly those of the Gabler edition, impose further numerical discipline on Ulysses. The line numbers produce a hierarchy that allows humans and machines alike to arrive at a shared understanding of textual location:

Line (beginning at 1 and incrementing by 1 within each episode)

Episodes (1–18, or “Telemachus” to “Penelope”)

Ulysses (the whole)

This rationalization functions so powerfully, not only in digital projects but also in conventional academic citation, because it assigns to each location in the text—with some exceptions, such as images—a line, and every line belongs to an episode, and every episode belongs to Ulysses. The hierarchy of information allows shared understanding of reference points.

Though created before the age of contemporary digital humanities, the line/episode/book hierarchy produces a kind of standardization—simple, technical, and reductive—that is enormously useful for digital methods. For example, I embedded into Ashplant a script that combs parts of the site for references to Ulysses, based on a standard citation format of “(U [episode].[line(s)]),” then generates automatically a list of references to an episode, with a link to each source page.

These references point to entries in our collective lexicon of key terms in Ulysses. The students’ lexicon entries together constitute a playful, inventive exploration of the book’s language. The automated construction of the list itself, however, relies on an episode-line hierarchy that has none of that playfulness or invention.

For playful inventiveness in a hierarchy of location, we can turn instead to Stephen Dedalus in Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, who reads the hierarchical self-location he has written on the flyleaf of his geography book:

Stephen Dedalus

Class of Elements

Clongowes Wood College

Sallins

County Kildare

Ireland

Europe

The World

The Universe (Joyce 2003, 12)

Stephen’s hierarchy is personal and resistant, not only containing the humorously self-centered details of his hyper-local situation but also excluding, for instance, any layer between “Ireland” and “Europe” that would acknowledge Ireland’s containment within the United Kingdom. It also confuses categories: although the list seems geographical—appropriately, given its location on a geography book—it contains some elements that would require additional information to become geographical (“Stephen Dedalus,” “Class of Elements”), and others whose mapping would be contentious (“Ireland,” “Europe”). It even contains an element, “Class of Elements,” that constitutes a self-reflexive joke about the impulse to classification that the list satirizes.

Such knowing irony does not infuse the hierarchies that drive much of our work in the digital humanities. That work requires schemes of classification that rely on one element’s containment within another. Consider what “Words API” claims to be “knowing” about words:

An API, or Application Programming Interface, provides methods for different pieces of software to communicate with one another in a predictable way. Words API, “An API for the English Language,” performs this function by adding hierarchical metadata to every word. That metadata, in turn, allows other software to draw on that information by searching for all the words that refer to parts of the human body, for instance, or for singular nouns. In other kinds of DH applications, such as textual editions that are part of the XML-based Text Encoding Initiative, the hierarchical relationships are often hand-encoded: feminine rhyme is a type of rhyme, and rhyming words are sections of lines, which are elements of stanzas, and so forth.

The utility of these techniques is not surprising. Stanzas do generally consist of lines, transitive is a type of verb. The reliance on these encoded hierarchies echoes the methods of New Criticism, such as Wellek and Warren’s hierarchical sequence of image, metaphor, symbol, and myth—for them, the “central poetic structure” of a work (Wellek and Warren 1946, 190). For contemporary scholars more invested in decentering and poststructuralism, however, the echo of New Critical hierarchies in DH is unwelcome. Centrality implies exclusion; structure implies oversimplification; formal hierarchy implies social hierarchy. Or, as John Bradley writes, “XML containment often represents a certain kind of relationship between elements that, for want of a better term, can be thought of as ‘ownership’” (Bradley 2005, 145). Even for scholars working specifically to counteract the hierarchical containments of XML, the attempt can lead—as in Bradley’s work—to the linking of multiple hierarchical structures rather than the disruption of hierarchical organization itself.

Problems of “Subtle Things”

Addressing the challenges of encoding historical materials in XML, Bradley describes the limitations of hierarchical classification. “Humanities material,” he writes, “sometimes does not suit the relational model,” and he cites the Orlando Project’s opposition to placing its data in a relational database because it wanted to say more “subtle things” than the relational model could express (Bradley 2005, 141).[9] Bradley responds to that challenge with an ingenious method of integrating the capabilities of SQL databases into XML, solving the problem of expressing how a name in a historical document might refer to one of three people with discrete identifiers in the database. Even this problem, however, involves a relatively simple kind of uncertainty, representable on a line between “certain” and “unlikely.” The data being encoded is used for humanistic purposes, but the problem itself is not especially humanistic: it assumes an objective historical reality that can be mapped, with varying levels of confidence, onto stable personal identifiers.

The data of Ulysses presents additional difficulties, many of which are specifically literary, as the students working on Ashplant have repeatedly found. In one case, a group of them sought to document every appearance of every character in Ulysses. That data has clear utility for readers: when made searchable, it could assist a reader by identifying, for a given episode and line number, the active characters, perhaps adding a brief annotation to each name. Many earlier aids to reading the novel offer descriptions of the main characters, but the students set out to develop a resource that was more comprehensive and more responsive to a reader’s needs at a given place in the text. The students quickly discovered that identifying and describing a handful of major characters is easy; identifying all of them and their textual locations is not just a bigger problem but a fundamentally different one.

Take, for example, the novel’s dogs. We had established early on that non-human entities could be characters in our classification, given Joyce’s attribution of speech and intention to, say, hats and bars of soap. At least one dog seemed clearly to reach the level of “character”: Garryowen, the dog accompanying the Citizen in the “Cyclops” episode. According to one of the satirical interpolations of the episode, Garryowen has attained, “among other achievements, the recitation of verse” (12.718–19), a sample of which is included in the text. For the purposes of our data and accompanying visualization, we therefore needed basic information about the character, such as its name and when it appears in Ulysses.

The name creates the first problem. The description of the dog in “Cyclops” identifies it as “the famous old Irish red setter wolfdog formerly known by the sobriquet of Garryowen and recently rechristened by his large circle of friends and acquaintances Owen Garry” (12.715–17). In itself, the attribution of two names to one being is not a problem. For instance, Leopold Bloom can be “Bloom” or “Poldy,” but switching between them does not rename him. In Ulysses, such an entity could take the names “Garryowen” and “Owen Garry.” As long as the underlying identity is stable, this kind of multiplicity (two names at two different times) can fit easily into a relational database.

But Ulysses does not work so simply. Within the fiction, the renaming of the dog has questionable reality-status.[10] The “rechristening” has no durability within the narrative; it exists only in the context of one satirical interpolation, and subsequent references to the dog revert to “Garryowen.” Arguably, if our task is to describe the characters that are real within the world of the novel, the name “Owen Garry” has no status at all, as it attaches more to the voice of the temporary narrator than to what we could imagine as the real (fictional) dog.

However, we could just as plausibly say that, in the fiction, “Owen Garry” must not only exist but also be recorded as a separate character representing the temporary re-creation of Garryowen by this narrative voice. All of this messiness anticipates the further complications of the hallucinatory “Circe” episode, in which Bloom is followed by a dog that metamorphoses among species—spaniel, retriever, terrier, bulldog—until Bloom addresses it as “Garryowen,” and it transforms into a wolfdog. The dog might say, as Stephen does, “I am other I now” (9.205). Joyce’s method relies on the unresolvability of these ambiguities.

Emily Mester, the student who took the lead on the Ashplant character project, brought the transforming dog to our working group as a problem of data entry. We discussed how the problem stemmed from a breakdown of classification: rather than allowing the reader to rely on conventional relationships between sets and their elements (living things include humans and other animals, which include dogs, which include species, which include individual dogs), Joyce’s transforming dog implies a relation in which the individual dog contains multiple species. Our conversation led us to consider the dog as a device through which Joyce upends hierarchies of containment by attaching the name “Garryowen” to a dog, or an assortment of dogs, whose characteristics arise from the surrounding narration.

We realized together that the exercise of entering data into our spreadsheet led us to new questions about earlier scholarship on Ulysses. We found, for example, that Vivien Igoe assumed that Joyce’s Garryowen represented a historical dog of the same name, as in her statement that “Garryowen, who appears in three of the episodes in Ulysses (‘Cyclops’, ‘Nausicaa’, and ‘Circe’), was born in 1876” (Igoe 2009, 89). Although Igoe subsequently notes that Joyce distorts Garryowen for the purposes of fiction, this sentence still relies on several related presumptions for the purposes of historicist explanation: that the historical and fictional Garryowens are the same, that the Garryowen of Ulysses has the species identification of the historical dog (“famous red setter” [Igoe 2009, 89] rather than the “Irish red setter wolfdog” of “Cyclops”), and that within Ulysses, the fictional dog maintains a constant identity across episodes.[11] Reading phrasing such as Igoe’s in light of our questions about Garryowen led the Ashplant group to consider the confrontation between certain kinds of historicist methods with poststructural skepticism.

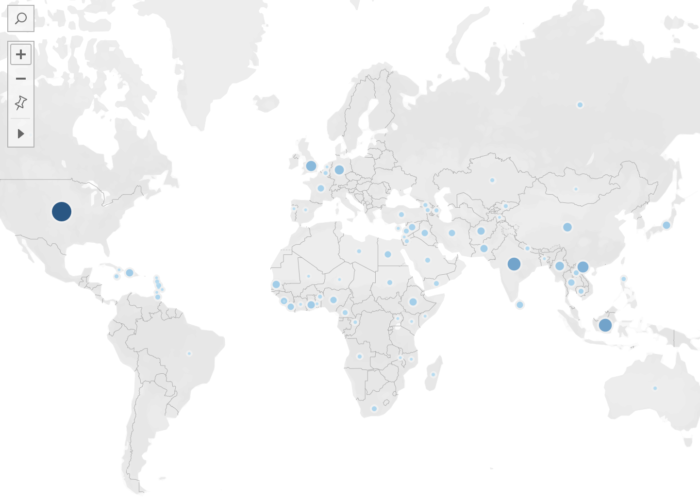

As the students continued to develop Ashplant, they discovered more and more examples of data entry problems that gave rise to probing discussions of Ulysses and, often, of how fictions work and how readers receive them. We sought, for instance, to map the global imagination of Ulysses, resisting the tendency Drucker had criticized of producing simplistic, naïve Dublin-centric visualizations of the “action” of the book. Instead, our map included only places outside of Dublin. For that subproject, guided by the student Christopher Gallo, we asked, How do we map an imaginary place? One that a character remembers by the wrong name? One that seems to refer to a historical event but puts it in the wrong place? For another part of the project, led by Magdalena Parkhurst, we created a visualization of the Blooms’ bookshelf that has been disrupted in “Ithaca,” and we needed to represent books with missing, incorrect, and imaginary information according to our research into historical sources.

Again and again, we found that the parts of Ashplant that appeared to involve the simplest kinds of data entry prompted us to have some of our deepest conversations about Ulysses, often leading us to further reading in contemporary criticism and theory. We found that, as Rachel Buurma and Anna Tione Levine and have argued,

Building an archive for the use of other researchers with different goals, assumptions, and expectations requires sustained attention to constant tiny yet consequential choices: “Should I choose to ignore this unusual marking in my transcription, or should I include it?” “Does this item require a new tag, or should it be categorized using an existing one?” “Is the name of the creator of this document data or metadata?” (Buurma and Levine 2016, 275–76)

Though our project is not archival, our experience has aligned with Buurma and Levine’s argument. Undergraduate research, which “has long emphasized process over product, methodology over skills, and multiple interpretations over single readings,” is well situated to foster the “sympathetic research imagination” necessary for creating useful digital projects. As our process became product, we felt more powerfully the constraints of using the “reductive and literal” tools that concern Drucker. No matter how nuanced and far-reaching our conversation about Garryowen had been, for instance, the needs of our spreadsheet compelled us to choose: is/are the transforming dog(s) of “Circe” appearances Garryowen or not?[12]

We found that the machinery of data entry and visualization produced what Donna Haraway calls the “god trick” of producing the illusion of objectivity, even when our conversations and methods aspired to privilege, in Haraway’s words, “contestation, deconstruction, passionate construction, webbed connections, and hope for transformation of systems of knowledge and ways of seeing” (Haraway 1988, 585).[13] Our timeline-based visualization of character appearances, for example, could not resist the binary choice of yes or no; even a tool that could represent probability would not be capable of representing non-probabilistic indeterminacy in the way that our conversation had. We needed to find other ways to make Ashplant into a site that produces a humanistic experience for its readers as well as its creators.

Ways Forward for Humanism in Undergraduate Digital Studies

This essay will not fully solve the problem it addresses: that digital methods gain some of their power by selecting from and simplifying complex information, sometimes in ways that run contrary to humanistic practices. Like Buurma and Levine, however, I find that the scale and established practices of undergraduate research create opportunities to do digital work that minimizes the problem and may, in fact, point to approaches that can inform humanistic digital work in general. With that goal in mind, I offer a few propositions based on our Ashplant team’s experience to date.

- Narrate the problems. Undergraduate research often operates at a scale that allows for hand-crafted digital humanities, in which the consequences of data manipulation can become the explicit subject of a project. The structure of Ashplant allows us to explain the problems of documenting character and location in Ulysses, and it also provides space for a wider range of student research: an analysis of Bloom’s scientific thinking and mis-thinking in “Ithaca,” a piece about Ulysses and the film Inside Llewyn Davis that uses hyperlinks to take a circular rather than linear form, and students’ artistic responses to the novel. The scale of undergraduate research allows it to become an arena for confrontation with and immersion in the problems created by the intersection of data science and the humanities.

- Connect conventional research to digital outcomes. Ashplant has at its heart an annotated bibliography, for which students read, cite, and summarize existing scholarship. Creating such a bibliography in digital form—specifically, with the bibliographical information in a database accessed through our web interface—enables searchability and linking. The bibliography thus becomes the scholarly backbone of the site, linked from and linking to every other section. Contributing to this part of the project grounds the students in the kind of reading and writing they have done for their other humanistic work, while also illustrating the affordances of the digital environment.

- Use the genre of the hypertext essay. Writing essays that combine traditional scholarly citation with other means of linking—bringing a project’s data to bear on a problem, connecting the project to other digital collections and resources—allows students to experience and demonstrate the impact of their digital projects on scholarly argumentation. Ashplant therefore includes a section of topical essays and theoretical explorations, addressing subjects from dismemberment to music. These essayistic materials link to and, importantly, are linked from the parts of the site that are based more explicitly on structured data. Our visualization of the global locations of Ulysses can lay the foundations for discussions of the Belgian King Leopold and the postcolonial Ulysses, for example, and a tool we developed for finding phonemic patterns in the text became the prompt for Emily Sue Tomac, a student specializing in linguistics as well as English, to undertake a project on Joyce’s use of vowel alternation in word sets such as tap/tip/top/tup. Hypertext essays can reanimate the complexities and contestations hidden by the god trick.

- Make creative expression a pathway to DH. My initial design Ashplant involved an unconventional division of labor. For the most part, students wrote the content of the site, while I took the roles of faculty mentor, general editor, and web developer. As the site evolved, so did those roles, and I perceived an important limitation of our model: students were rarely responsible for the visual elements of our user interface, and their interest in that part of the project was growing. The students saw the creative arts as a means of resisting the constraints of digital methods, and some of them created art projects that now counterbalance the lexical content of the site. When I designed a new course on digital methods for literary studies, therefore, I put artistic creativity first.[14] In that class, the students learned frameworks for discussing the affordances and effects of electronic literature, and we applied those frameworks to texts such as “AH,” by Young-hae Chang Heavy Industries; Illya Szilak and Cyril Tsiboulski’s Queerskins: A Novel; and Ana María Uribe’s Tipoemas y Anipoemas.[15] These works model a range of approaches to interactivity and digital interfaces. Therefore, all of our subsequent work in the semester—from the creation of the students’ own works of electronic literature, to the collection and presentation of geographical data, to writing Python scripts for textual analysis—takes place after this initial framing of digital work as a set of creative practices.

The complexity of humanistic inquiry does not involve solving well-defined problems with clear endpoints and signs of success. Our wholes have holes. As I have worked with my students on Ulysses, we have come to embrace a practice of digital humanities that puts creativity, resistance, and questioning at its heart, even (or especially) when we use the tabular and relational structures that appear at first to build walls within the imaginative works we study. Asking questions as simple as “What do we call this chapter of Ulysses?” and “When does this character appear?” has led my students to think and play and draw, representing contours of absurdity and art that help draw new maps of undergraduate study in the humanities.

In some ways, that new mapping takes part in the tradition I have described here: the translation and even reduction of textual complexity into reference materials that help students grasp Ulysses and begin the process of making meaning of and around it. In other ways, however, Ashplant has led us to a practice of digital humanities more aligned with Tara McPherson’s emphasis on “the relations between the digital, the arts, and more theoretically inflected humanities traditions” (McPherson 2018, 13). The scale of undergraduate pedagogy allows spreadsheets, essays, maps, and paintings to grow from the same intellectual soil, maintaining the value that structured data has long provided while preserving the complex energies of humanistic inquiry.