Introduction: The Origins of a Gallatin ePortfolio

The Gallatin School of Individualized Study at New York University (Gallatin) offers a Bachelor of Arts and a Master of Arts in individualized study. The ePortfolio project focuses on the BA program. Students at Gallatin develop their own programs of study by combining Gallatin’s core curriculum of small, interdisciplinary seminars and workshops with courses in other NYU schools. Additionally, students pursue independent studies (one-on-one projects with faculty), tutorials (small group projects), private lessons, and internships. This course of study culminates in a final oral exam, called the colloquium, in which students demonstrate their knowledge about a select number of significant texts.

With just over 1,600 undergraduate students and approximately 150 graduate students, Gallatin is a relatively small school housed within a large research university. Being an individualized study major in a small school that is part of a very large university, on a distributed urban and global campus, can be an isolating experience. Because of this, Gallatin has used active, focused faculty advising as a cornerstone of its curriculum from the very first formative years as a program in 1972, and then as a division in 1976. But in 1976, Gallatin had only 200 students (London 1992, 7). By 2008, with a much larger student body, there was agreement among faculty members that students could benefit from a platform that encouraged reflection and collaboration.

This paper outlines three distinct ePortfolio platforms the school developed in an attempt to facilitate this student need for reflection and collaboration. The first was a shared, multi-university initiative to build out the promising Sakai OAE (Open Academic Environment) into an academic-social-networking system with ePortfolios as a main component. The second was based entirely on Google Drive, and centered around the collection of course assets. And the final, still ongoing, platform is built around WordPress, which attempts to account for the limitations of the the first two.

During the Fall of 2009, several factors led to the consideration of an ePortfolio for Gallatin students: social media; advancements in ePortfolio and learning management system (LMS) software; digitally native content; and the expansion of the arts and experiential learning at Gallatin. Moreover, many students were coming upon their culminating experience, the colloquium, underprepared, specifically in the integration of coursework spanning their entire academic career. Students, now accustomed to platforms like Facebook and Google Docs, were wondering why there was not an academic corollary.

During a focus group with students concerning the enhancement of the school’s LMS, several ePortfolio-related themes emerged. Where students used to be satisfied focusing on their individual concentrations and learning goals, they were now interested in community. Several students at the Fall 2009 LMS focus group asked for a way to find other students with similar academic interests. Additionally, participants mentioned how they would like to share their academic work across courses, in ways that would surface meaningful connections between students. These students’ comments were aligned with the research on ePortfolios. Bryant and Chittum (2013, 189197) note that successful ePortfolios enable students to share and collaborate on work spanning their entire program. This finding is consistent with trends in ePortfolio use at the time, where less course- and program-based, and more collaborative ePortfolios were gaining in popularity (Brown, Chen, and Gordon 2012, 129-138).

This focus group conversation became one about effective ePortfolios. The students recognized the need for a tool to capture, synthesize, and share their academic careers, a way to “utilize Facebook[-like]…prefab micro-sites…So that people could upload different documents” (personal communication). Several students advocated for a platform that encourages self-assessment and peer assessment, foundational elements of good ePortfolio design (Wade, Abrami, and Sclater 2005, under “Student Self-regulation”).

The author, Likos, in conversation with the faculty, was also coming to a similar conclusion: a tool was needed that could help scaffold the development of the individualized concentration; encourage the synthesis of experiential, performative and academic learning; and allow for the communication and articulation of the students’ work. Hayward et al. explain how ePortfolios can help achieve just these goals, emphasizing the tool’s ability to help integrate different modes of learning (2008, 140–159). Additionally, the ePortfolio is specifically valuable in interdisciplinary studies. Field and Stowe explain that the “the longitudinal nature of the process,” which provides explication of an entire learning journey, “can be used effectively to validate the interdisciplinary process and to communicate the process to internal, and external audiences” (2002, 268).

As a result of our student focus group, faculty discussion, and research on ePortfolios, a specific articulation of the requirements for a Gallatin ePortfolio platform emerged:

- The system must allow for text-based and digitally native content.

- Assets must be flexibly shareable—to students in a course, the school, the University, and the outside world.

- Assets must be taggable in a manner that encourages searching, browsing, filtering, and sorting.

- The ePortfolio must evolve from a student’s first year through their life after college.

- The platform must allow for the creation of attractive public-facing websites.

A landscape survey of existing software at the time found that none could satisfy all of these criteria. Most ePortfolio platforms were still focused on assessment (Clark and Eynon 2009, 18–23), which was not the core requirement of a Gallatin ePortfolio. With this in mind, we broadened our search beyond specific ePortfolio software to platforms that could act more as a development toolkit. This led to Gallatin’s, and later NYU’s, significant engagement with Sakai.

Sakai OAE and ATLAS: A Grand Vision Leads to Loss of Focus

Just as the benefits of an a ePortfolio system were becoming clear to the Gallatin community, so too were these benefits being recognized by another department at the University, the Liberal Studies Program. Confronted with similar requirements, an ePortfolio project was initiated in 2008 with the help of a National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) Digital Humanities Start-Up Grant (Apert 2011). Like Gallatin, the Liberal Studies Program was aiming for a system that would support content authoring, management and tagging, private and public-facing ePortfolios, and academic networking. Gallatin was thus a natural partner, and joined the initiative in 2008. By 2009, Liberal Studies and Gallatin were joined by 8 additional NYU entities.[1]

With this infusion of interest and capital, a new ambition grew, and a new, more robust platform was needed to meet these ambitions. Liberal Studies, already using Sakai CLE (Collaboration and Learning Environment) for the first iteration of its ePortfolio, recognized the potential of the then nascent Sakai OAE (Open Academic Environment). The promise of OAE was a user-, group-, and content-centered system. As Apert explains, Sakai OAE “uses the…concept of groups to replace the more rigid structure of sites in traditional learning management systems (LMS)….In Sakai OAE…tools are ‘widgetized,’ meaning they exist as free-floating modules that can be pulled into any page” (2011). This is in contrast to Sakai CLE, and most LMSs at the time, which were built with the course at the core.

After several months of collaboration, a working group of faculty and staff members representing the ten schools and departments committed to this project were so enthusiastic about the promise of a user- and content-centered academic networking platform, that by mid-2010 NYU had become the most significant partner in a multi-university alliance to build the next generation LMS (Hill 2012). Along with Cambridge University, the University of California, Berkeley, Indiana University, Georgia State University, and Charles Sturt University, NYU shared a seat on the Sakai OAE steering committee, and NYU’s Chief Digital Officer, David Ackerman, was appointed to the position of Sakai Board Chair.

But by the end of 2010, this was already something very different than the ePortfolio project on which Gallatin had first partnered with NYU’s Liberal Studies Program. The Gallatin ePortfolio had very specific requirements around content and sharing, which though part of the roadmap for Sakai 3, would now have to share space with all of the traditional functions of an LMS. With Sakai CLE representing five percent of the higher-education LMS market at this time, legacy tool support and development was no small matter (Green 2013, 23). As a member of the NYU Sakai 3 working group, Likos had to collaborate with representatives from nine other schools and departments at NYU to set priorities that would then compete with those from the six other Sakai steering committee member universities. Predictably, this produced a very large set of requirements.

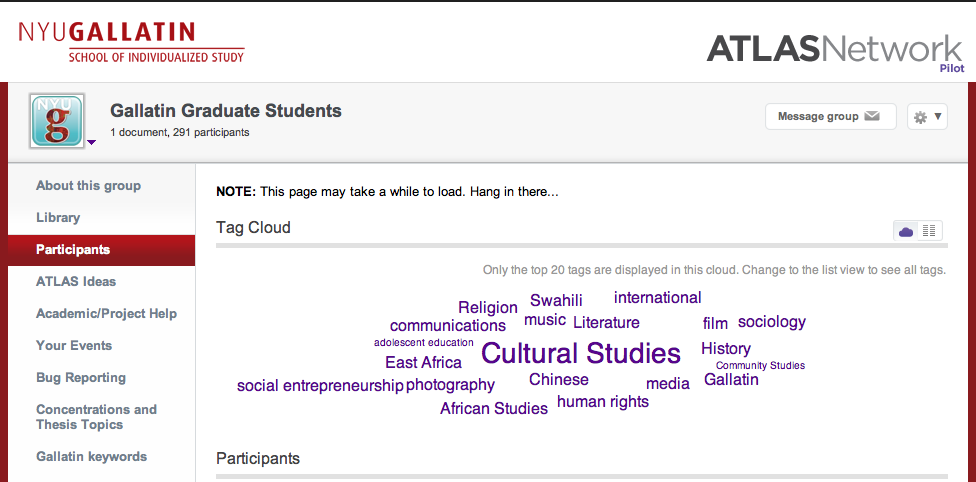

By Spring 2011, nearly two years after the first discussions about ePortfolios for Gallatin students occurred, the first beta iteration of NYU’s version of Sakai 3, ATLAS (Advanced Teaching, Learning, and Scholarship) network, was running. Though our initial plan was to help undergraduates synthesize and share their concentrations, we decided our first pilot would be with graduate students for two reasons. First, this initial iteration of ATLAS had severe performance and feature shortcomings. It simply could not handle more than dozens of users at a time, and many of the features supporting content creation, tagging, and sharing were not yet built. The second reason was that our graduate students were beginning to ask for a simplified platform for finding each other. That is, they were happy to have an enhanced directory of students that could be filtered according to academic interest. Given the limitations of ATLAS, it made more sense to pilot a more condensed feature set to a smaller group of 150 students. While supporting this pilot for graduate students, we continued to push for development of features that would turn this into a true ePortfolio for our BA students.

By Spring 2012, with the 1.1 version of ATLAS released, we were not significantly closer. The platform was now more capable of handling larger numbers of users, the content authoring interface was better, but it was not an ePortfolio. The centrifugal force of multiple schools’ and universities’ competing requirements and features continually pulled at the center until there was barely a center at all. In the end, it was neither a fully functional LMS or an ePortfolio. This, combined with the emergence of Google Apps for Education and the Universities’ adoption of it, and new LMSs like Canvas and D2L, spelled the end for ATLAS and the larger Sakai OAE project. By the Spring of 2012, all of the remaining large university funding partners left the project, and NYU soon followed suit, officially sun-setting the pilot on January 22, 2013.

In its final iteration, Gallatin’s version of ATLAS included academic profile information for 150 graduate students, as well as a tag cloud (see Figure 1) to help visualize the weight of academic interest areas. It contained no other ePortfolio assets, though technically, it could have. Our assessment of the platform was that it failed in at least some way in each of the five categories of requirements initially laid out. The most successful feature was the academic interest tag cloud, and if extended to content, as originally envisioned, it could have been a valuable way for students to share and collaborate.

There are many lessons to be learned from Gallatin’s Sakai OEA/ATLAS journey, foremost of which is that Gallatin handed over its agency in developing an ePortfolio platform in the hope of being part of something that would be much more. The project grew so large, so quickly, that the competing requirements of multiple universities and schools became increasingly difficult to manage and fund. Another takeaway was that the mass of the “academic social networking” feature set was so great that it pulled almost all the development and pedagogical energy into its gravity well. The promise of a “Facebook for the academy” was so alluring that we shifted too much attention from the core elements of a successful student ePortfolio.

Google Drive: Familiarity without Scalability

It was from this place that a re-conceived ePortfolio platform was born. In the spring of 2013, a reconfigured Gallatin steering committee was assembled to review the failures of the ATLAS project and to recommend a new way forward. One of the first issues we uncovered was that ATLAS privileged technology over good pedagogical design. We hoped the technology would allow for robust connections among students without specific prescriptions, as was the case in other social networks. The idea was that students would upload any assets they thought relevant to their concentrations, and the metadata would do the magic of surfacing the relevant, connected information. This proved to be technically very difficult, and not clear at all to the student participants. Additionally, Gallatin had prescriptions that could and should be applied to ePortfolios:

- Course documents: syllabi, papers, readings.

- The booklist and rationale: documents prepared in advance of the colloquium that contain 20 to 25 texts that cover multiple disciplines and historical periods related to the student concentration, and a five- to eight-page essay that articulates the central themes that are represented by the booklist.

- The Intellectual Autobiography and Plan for Concentration (IAPC): a two- to three-page essay, completed at the end of a student’s sophomore year, in which students reflect on their educational progress and describe their areas of interest.

- Plans of Study: forms filled out every semester outlining the students’ registration plans for the following semester, and how these relate to their individualized course of study.

Starting from these assets, the committee recognized an opportunity to focus the scope of a project that had become so large with ATLAS to a simpler set of requirements. This new conception asked, what is the easiest and most stable system that students can use to store and share their course and concentration documents? Taking this together with the original prerequisites from 2009, and the lessons learned from ATLAS, an updated requirement set asked that:

- The system allows for text-based, as well as multimedia content.

- All assets be shareable to faculty, advisers, other students, and the public.

- Assets in the ePortfolio be accessible to students after they graduate.

- The platform already be built, stable, technically vetted, and inexpensive.

Taking these into account, it was a very easy decision to pilot a new ePortfolio project with Google Drive. NYU’s investment in Google Apps for Education was increasing, and a University-led ePortfolio landscape survey indicated that Google Drive was a viable ePortfolio alternative for simple projects. Additionally, it was a familiar product, with a support and training structure in place. In terms of storage and performance, we already knew that it could handle thousands of students and assets, and we knew those assets could be securely shared with individuals and groups using existing NYU credentials. Furthermore, there was no direct cost to Gallatin. The platform and the central support was free, and students would keep their Google accounts, including their ePortfolios, after graduation. With the benefits of a Google Drive ePortfolio clear, and the cost to adoption low, it was decided that a new pilot would launch in the Fall of 2013. Gallatin would pre-populate the following folders and documents in all students’ drives:

- Courses

- Syllabi

- Papers

- Readings

- Brainstorming

- Bibliography (citations of key texts)

- “Concentration” document (notes from adviser meetings, thoughts on classes, ideas about one’s concentration)

- Plans of Study (saved copies of the Plan of Study forms)

With both the ATLAS and the Google pilots, the steering committee considered making the ePortfolio mandatory, but both times it was decided that the administrative burden on faculty was too great. With ATLAS, the ePortfolio component was not well defined, and the system not robust enough. The Google Drive ePortfolio was well defined, and the system was robust enough, but if we were going to utilize course registration holds—or use some other constraint—it meant either the faculty advisers or some other academic staff would need to review and approve ePortfolios. It was felt that Gallatin did not at the time have the resources to incent, train, and support the faculty and staff to perform this task well. Instead, beginning in the Spring of 2013, we undertook a marketing and training campaign. This included presentations at faculty meetings, online video demonstrations, and orientation training sessions for students.

The technical administration of the ePortfolios was fairly simple, but not straightforward. Because the University’s implementation of Google Apps could not ingest school and class directory information, there was no way to automate the group creation of the “Gallatin ePortfolio,” or easily generate unique ePortfolio URLs. This all required additional manual work.

In early Fall 2013, the first set of student ePortfolios were provisioned. These included all 269 Gallatin first-year students. An email from the dean was sent to these students with a link to their ePortfolios and instructions on how to use them. Simultaneously, messaging went out to faculty encouraging them to remind students about the ePortfolio. The same basic structure for the ePortfolios remained in place through the Fall 2014 semester, but by the third semester of the pilot we had added sophomores and juniors.

From the student perspective, the system worked well. Students that chose to create an ePortfolio reported no issues creating and storing content. There was also very little student training required. But by the second semester, the University began to have trouble provisioning the accounts and setting permissions. The Google Apps administrators had to do this with a series of scripts, and there was concern that any change Google made to the product, which was not uncommon, could break the scripts. Additionally, it was at this time that we realized there were little to no options for getting data from the system. Even something as simple as getting a count of how many students were placing content into their ePortfolios was only possible by manually, visually checking each student’s ePortfolio folder. In the end, we used a randomly generated number set to choose a statistically significant sample of ePortfolios to manually check for content. By the final pilot semester, Fall 2014, only 1.9% of students had placed any content into their ePortfolios.

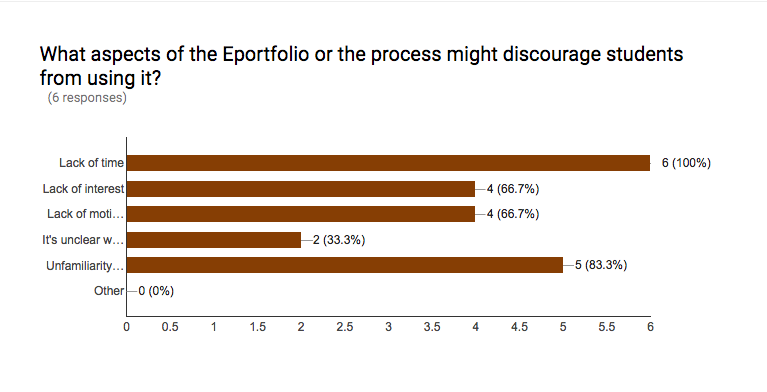

In summation, the Google Drive ePortfolio platform failed in several areas. Most compelling was the modest adoption rate, but the difficulty in extracting metrics from the system, and increasing difficulty provisioning accounts and permissions were also important. For these reasons, it was decided that Fall 2014 would mark the end of this pilot. Though there were technical limitations, it was the adoption rate that had the most impact in our final assessment. In discussions with students and faculty, it became clear that this pilot offered little in the way of incentive or injunction. Their use rate was very low in part because there was no appealing public-facing aspect of the ePortfolios, but even more significantly because of the way the ePortfolios were presented and taught. It had been decided to market the ePortfolio to students and faculty, instead of train faculty to actively engage with students around the ePortfolio in their courses; we now see that decision as a mistake. These two key issues we hoped to address in the next pilot.

WordPress: Re-centering on Reflection

Taking into account the lessons learned from our ATLAS and Google Drive experiences, we are now in the midst of our third iteration of ePortfolios at Gallatin, this time using NYU’s WordPress installation, Web Publishing, which launched in August of 2014. Like Google Drive, Web Publishing comes with NYU IT support and training, provides adequate storage for our multimedia needs, is integrated with our user-authentication system, and is a no-cost, portable platform. Unlike Google Drive, however, Web Publishing enables us to create a template tailored to the needs of our students, so that we are now able to easily deploy sites as needed. More important than the authentication and storage benefits, however, is the built-in reflective space Web Publishing offers, as well as the ability to create visually appealing, customizable, public-facing websites with granular control over visibility. Our hope is that the personalization achieved through reflective blog posts and customization features will give students a strong sense of ownership over their ePortfolios, thereby incentivizing adoption rates.

With a renewed focus on reflection, the committee has decided to diverge from the structure adapted for Google Drive, which functioned primarily as a repository of work. Our new template thus contains areas for four main types of reflective content: the “about me” bio page, the course descriptions and expectations blog, the end-of-semester reflections, and an annotated bibliography (see Figure 2).

In addition to these pre-packaged content areas, students are encouraged to customize their ePortfolios in order to document all of their Gallatin-related experiences, including internships, study-abroad, and extracurricular activities, thereby creating a comprehensive repository that gives viewers both a general sense of the breadth and scope of a student’s intellectual trajectory, and the ability to drill down into the details of a particular term, course, or activity.

Participating faculty are being asked to integrate several activities into their courses that are designed to both kickstart student engagement with their ePortfolios, and to encourage students to begin thinking metacognitively about themselves as learners. Advisers are participating in the pilot by asking their advisees to see their ePortfolios. We believe that active involvement on the part of faculty and advisers will be a critical component to the success of the program.

On the first day of class, faculty ask their students to write a short bio for the About Me page. Not only is the ability to write a compelling bio a skill that will benefit students personally and professionally, it is also an exercise in narrating selfhood that should always precede engagement with digital identities, of which ePortfolios are a part. Moreover, sharing and discussing bios in a classroom environment promotes the development of learning communities that are so important to students’ mental health and wellness, and so critical to long-term academic success. Early in the semester, students are also asked to write a blog post containing the course descriptions for each class they take, accompanied by their expectations for these courses. By doing so, students will not only create a chronological record of the courses they take, they will be setting up personal learning goals that will help sustain their focus throughout the semester. These initial reflective posts are then connected to the reflections they are asked to write on the last day of class. In their “end-of-semester reflections,” students are asked to compare what they had expected to learn with what they actually learned, and to make a list of key texts from the semester. The blog is a space to assist students in reflecting on their learning as they develop over the course of each term, and to help suggest a direction for the coming term. Such reflections will allow students to document the evolution of their intellectual pathways, to make connections, and to generate questions for future research and for their advisers.

These reflections will act as a pre-writing activity, providing material for the IAPC, the booklist/rationale, and the colloquium, all of which require students to articulate their research interests and to identify thematic correspondence between the various areas of study. This, ultimately, is at the core of what we are trying to achieve: to help our students connect the dots. As the “school of individualized study,” Gallatin requires its students to design their own curriculum, in conjunction with an adviser. This self-directed learning model empowers students to actively engage in the development of their own education, and allows them to take a wide variety of courses, both at Gallatin and at other NYU schools (and beyond). But this learning model also comes with unique challenges. Because students are exploring many different subject areas, it is often difficult for them to articulate the connections and/or tensions between them. Milestone requirements, such as the IAPC due at the end of sophomore year, and the booklist/rationale required before the final senior colloquium, have been put in place as scaffolding, preparing students for the kind of scholarly synthesis that will be expected of them during their final oral examination. Yet these milestones are themselves rigorous requirements that will also, we believe, benefit from the kind of sustained reflection built into the design of our ePortfolios. The designated Annotated Bibliography page, for instance, is something students can build up over time, and can eventually become a direct precursor to the booklist and rationale.

Taken as a whole, the design of our ePortfolio template works to engage students in an ongoing reflective process that can best be described as active, inquiry-based learning. As Wozniak writes, “Reflection connects the components of the inquiry cycle and serves as the catalyst to move to the next level of learning and discovery. Information is transformed to knowledge and fragmented pieces of knowledge are connected through reflection” (2012, 221). Used as an advising tool, Gallatin’s ePortfolio provides a collaborative space in which to make those connections. By incrementally archiving, curating, and reflecting upon their coursework, students will essentially be self-scaffolding their learning, progressively building toward a stronger understanding of their own concentration. Wozniak also notes that reflection promotes integrative learning, a pedagogical approach in which students apply “multiple areas of knowledge and multiple modes of inquiry” (2012, 210) to real-world situations: “These learning experiences consider the whole student and foster lifelong learning skills. They engage students in making their own learning connections between their courses, professional career goals, co-curricular activities, campus involvement, community service, job experiences, and personal interests” (2012, 210). An integrative learning approach that considers the whole student is foundational to the mission at Gallatin, making a reflective ePortfolio system a natural addition to our program.

In order to ensure the successful implementation of an ePortfolio program that would be both meaningful for students and helpful to their advisers, we opted for an incremental, three-phase roll out plan:

| Phase | Phase Title | Duration | Dates | Primary Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Targeted Pilot | One Semester | 12/2015 to 5/2016 |

|

| 2 | Extended Pilot | Two Years | 9/2016 to 5/2018 |

|

| 3 | GallatinWide Implementation | Indefinite | 9/2018 + |

|

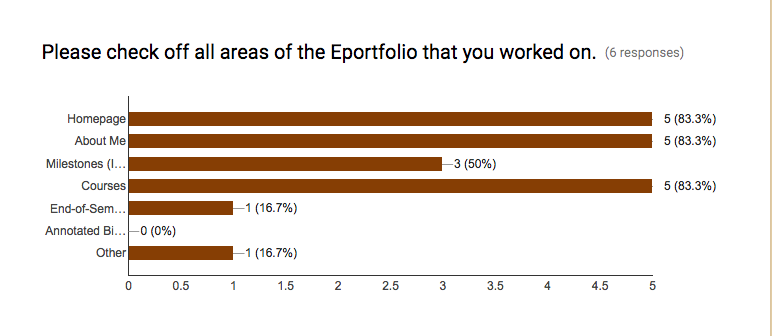

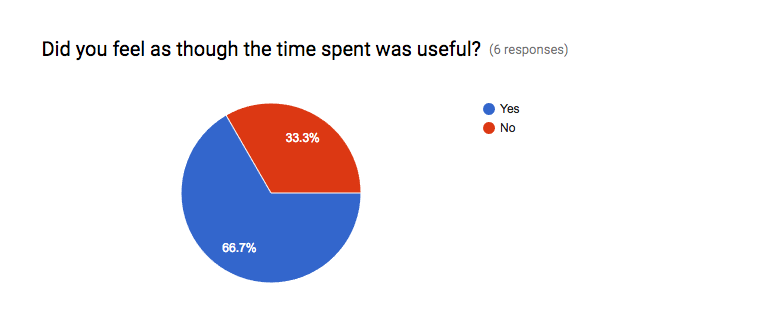

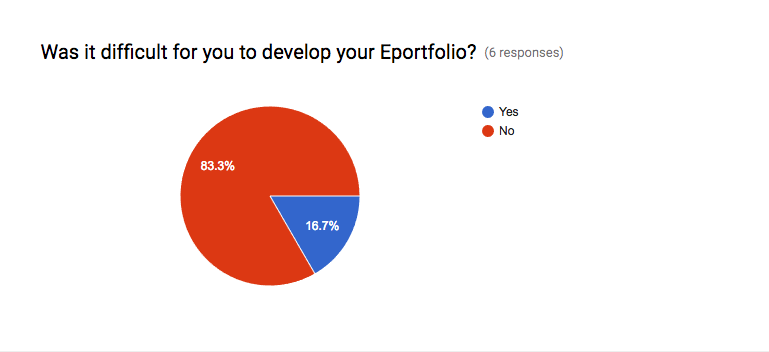

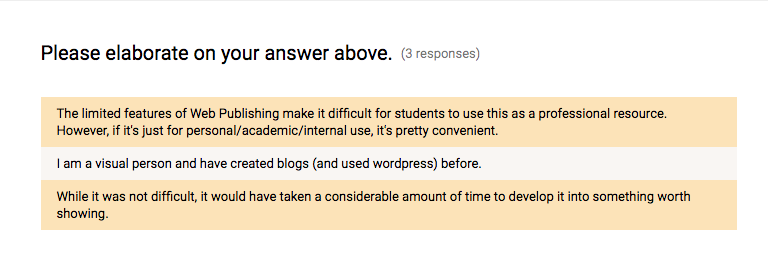

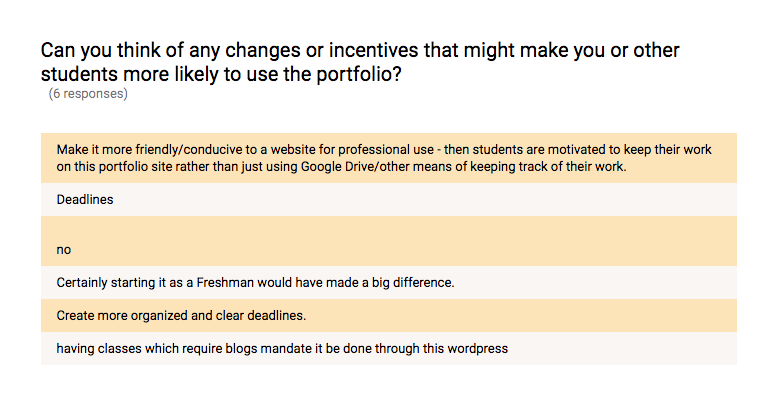

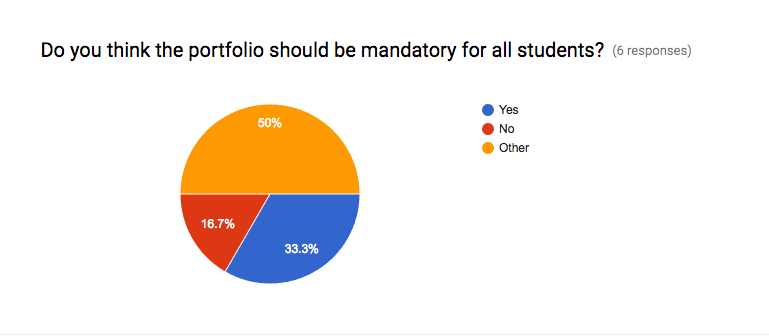

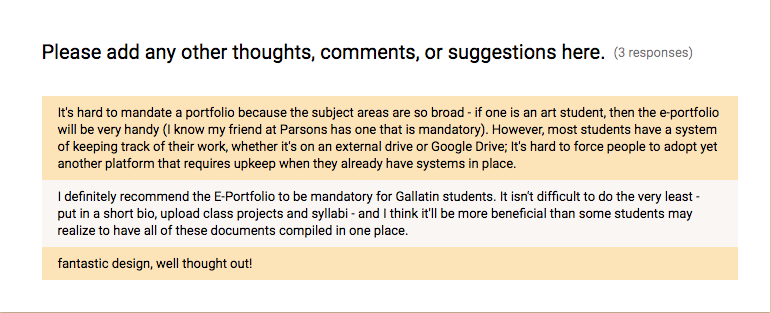

We have completed Phase 1, the Targeted Pilot, which included eight students hand-selected by their advisers. Our initial assessment of the Targeted Pilot is based on attendance, anecdotal feedback, questionnaire results (see Appendix), and completion rates. Although attendance at our group meetings was low, students responded positively to both the platform and the program. Our students had varying degrees of technological skills, yet all of them felt that WordPress was easy to learn and has long-term value. Participants responded favorably to the template’s design. Most of the students commented that the information architecture was intuitive, and several participants confirmed that the ePortfolio should be a space for highly curated materials, rather than a repository for all content, which may be best suited for Google Drive.

In terms of the ePortfolio program itself, the belief that a school-wide digital portfolio service would be valuable to Gallatin students was unanimous. Our primary purpose was to equip students with a tool with which to reflect on their progress, map out the next steps in their plan of study, and build towards future milestones. And to that end, the pilot succeeded. Not only did students report that an ePortfolio would have helped them complete specific milestones, they also expressed the belief that communication with their advisers would be improved. The surprising discovery was that students are increasingly expected to include ePortfolios in their application materials for graduate schools, internships, and other professional opportunities. This anecdotal information is confirmed in a study by Fowler (2012), who notes that an ePortfolio provides a better demonstration of student learning and skills than a standard resume because it represents a range of work, contextualized over time, and because it can be customized for multiple audiences. Our students likewise saw an opportunity either to use their Gallatin ePortfolio for such applications, or to become familiar with the process in order to create a separate ePortfolio.

Based on our assessment of the Targeted Pilot, we have entered Phase 2 of our implementation plan, which will run from September 2016 to May 2018. Our Extended Pilot currently includes our entire incoming first-year cohort, as well as 31 transfer students, for a total of 328 students and 19 faculty. Our ultimate goal is to seamlessly integrate ePortfolios into Gallatin’s curriculum, such that the incoming class of 2016 and all successive cohorts will view their ePortfolios as a dynamic, evolving, and natural component of the individualized and life-long learning goals at the core of Gallatin’s philosophy.

Conclusion

There have been vast cultural and technological developments since our first discussions about ePortfolios in 2009, including advancements in open-source technology, broader use of website building platforms, and shifting boundaries between social media and other web-authoring sites. These developments, in conjunction with an increasingly technologically sophisticated and visually literate student population, build an even stronger case for the implementation of ePortfolios at Gallatin. Having learned much over seven years of exploration, experimentation, and investment in ePortfolios, we have refocused our energy on the individualized philosophy at the core of Gallatin, prioritizing user experience over technical sophistication; focused, purposeful design over broad, generalized application; and, most importantly, pedagogy over technology. The emphasis on curation over archive and reflection over assessment promotes the kind of inquiry-based, integrative learning that is aligned with Gallatin’s mission, and that comprise the most promising pedagogical aspects of ePortfolios. Although early in our third ePortfolio iteration at Gallatin, we are encouraged by the enthusiasm with which our pilot participants received their customizable digital showcases, and hopeful that by the time our incoming class of 2016 becomes our graduating class of 2020, ePortfolios will have become a part of the fabric of Gallatin life.

'ePortfolios and Individualized, Interdisciplinary Learning: A Case Study' has 2 comments

November 28, 2016 @ 11:44 am Introduction /

[…] and Reflecting with ISUComm ePortfolios: Exploring Technological and Curricular Places” and “ePortfolios and Individualized, Interdisciplinary Learning: A Case Study,” offer examples of the trials and errors that programs have to negotiate as they create an […]

November 28, 2016 @ 9:15 am Table of Contents: Issue Ten /

[…] ePortfolios and Individualized, Interdisciplinary Learning: A Case Study Nick Likos and Jenny Kijowski […]