Introduction

In 2017, we participated in the University of Georgia’s (UGA) Special Collections Libraries Faculty Teaching Fellowship (SCLFTF) with a common goal of using archival collections and research methods to improve student writing. The fellowship offered us access to the expertise of the archivists and the space of the library for our student population in courses that we developed over the course of the program. As Wendy Hayden (2015, 404) has noted, “One challenge to integrating archival research into undergraduate courses has been the lack of practical advice and training in archival research provided by the field.” UGA’s archival Teaching Fellowship program provided us with crucial training in navigating the collections, working with finding aids, and understanding the “archival and library principles that support robust discovery and integration of relevant special collections materials” (Center for Teaching and Learning, n.d). During Spring 2017 semester, we each developed writing courses that would introduce students—both first-years and upper-level English majors—to archival research.

In this article, we describe the resulting archives-centered courses that we ran during Academic Year 2017–18 and discuss what we see as the most significant implications and opportunities for writing pedagogy that emerged from our experience. More specifically, we focus on the way this work foregrounded the technologies and materialities of texts and the collaborative and social nature of writing activities. In our courses, students, instructors, and librarians worked together to assemble and recontextualize archival materials through varied lenses and to produce new collaborative and multimodal texts that drew on that material in different ways, not necessarily simply as sources to be cited, but as inspirations for new ways of thinking about the past and future. Using archival research also gave our students the opportunity to think in new ways about how library-based material can produce new questions for exploration and how rare books and manuscripts can inform and inspire textual form and delivery systems in the digital age.

A key question for us was, “What does this kind of focus on textual materiality and physical interaction with primary texts bring to the table for writing pedagogy?” We observed that archival work is not, as typically depicted, solitary. As Matthew A. Vetter has noted, instructors who use the archives must collaborate with the librarians and often with outside organizations in charge of the archives as well; as such the authority in the classroom is dispersed throughout a community that is able to include and inspire the students (2014, 36–37). In each of our courses, we, the instructors, could provide some guidance but not prescribed rules for interaction with the archive, nor could we predict the outcomes of the class research.

The instructor generally curates the archive in an undergraduate setting, encouraging the students to work collaboratively with the texts to decode unfamiliar media. In addition, all work must be done at the archive, in reading rooms with strict rules, all of which takes reading out of the private space and into a social one. In her consideration of how to tap into the social affordances of digital media in scholarly publishing, Kathleen Fitzpatrick (2007) reminds us that “the technology of the book, and the literate public with which it interacted, produced a general trend toward individualizing the reader, shifting the predominant mode of reading from a communal reading-aloud to a more isolated, silent mode of consumption.” Classroom archival work shifts the focus back to reading as a communal act, serving as a model for cooperative writing. Fitzpatrick notes that “texts have thus never really operated in isolation from their readers, and readers have never been fully isolated from one another, but different kinds of textual structures have given rise to and interacted within different kinds of communication circuits.” One of these communication circuits is the work the archivist put into developing an archival collection. A well-developed collection has been built with an eye toward how the material is connected. So, by the time the collection is available to the public, the networks between the materials have already been established. Thus, archival work allows for an alternative “communication circuit” between readers and writers—both a return to more traditional (communal) modes and forward movement toward new modes of communication enabled by new media. In addition, by bringing different but related materials together, the archive allows students to see how diverse texts and types of media are in conversation with one another.

Following these textual considerations, we wondered, “How does archives-centered writing pedagogy promote the kinds of collaborative, curatorial, and recombinatory skills that are critical to digital age composition and literacy?” Building on the idea of archives-centered pedagogy as social and networked production and dissemination of knowledge, archival work in the undergraduate writing classroom also engages students in developing what the National Council of Teachers of English defines as 21st century literacies, including collaborative problem-solving, information management, and multimodal textual analysis and production skills. We were also inspired by the London Recut project, which uses digital film archives to allow communities to co-curate and remix archival material based on affinity and interest. As Recut’s Andrew Chitty notes (2011, 418), “Opening up film and video archives for use (not just viewing) by the wider public may create new narratives and interpretation, but it might also create new uses discovered by the users themselves.”

All of our courses were engaged in a kind of “meta-remix” composing process in that we asked students to mash up, combine, and translate primary source materials in a variety of ways, whether through historical reenactments, creation of mini collections/exhibits, or inspiration for digital textual design plans or their own zine compositions. These meta-remixes pressed students to find sources that provoked them to rethink their preconceptions rather than simply finding sources to use as evidence for preconceived arguments. In what follows, we provide individual case studies of our courses and conclude with some final thoughts on the benefits of archival work in writing courses.

Saxton’s ENGL 1102: “Scandal in the Archives” in First-Year Composition II

I was drawn to the archives and the archival Teaching Fellowship because of the ways in which archival materials demand investigative and engaged interaction. Susan Wells (2002, 58) has posited that the archives “prompt us … to resist early resolutions of questions that should not be too quickly answered”; this resistance might take the form of refusing answers, unearthing new depths or expanses for research, or necessitating new forms of expression to encapsulate its contents. My hope was to find materials that might inspire students to dig deeper into their sources to better analyze and contextualize them, but also to become comfortable with more open-ended research.

I coupled the archive’s lack of closure with the similarly open theme of scandal. Scandals, by their nature, offer a sense of mystery; even from the same smattering of facts, the connections between those facts and conclusions from them vary. Scandals disrupt modes of meaning and, as such, are interesting sites to examine rhetorical and contextual meaning. As Adrienne McLean notes, scandals are “discursive constructions as well as events, and it matters who controls the selection and omission of their narrative details” (2001, 2). Moreover, the culture in which the scandal occurs matters; what might be a scandal in 1900 might not elicit a reaction in 2018. In this way, scandal allows for a thorough investigation of who controls the narrative and how it is received; scandals, the students learn, resist fixed facts but instead show the ways in which meaning is constructed.

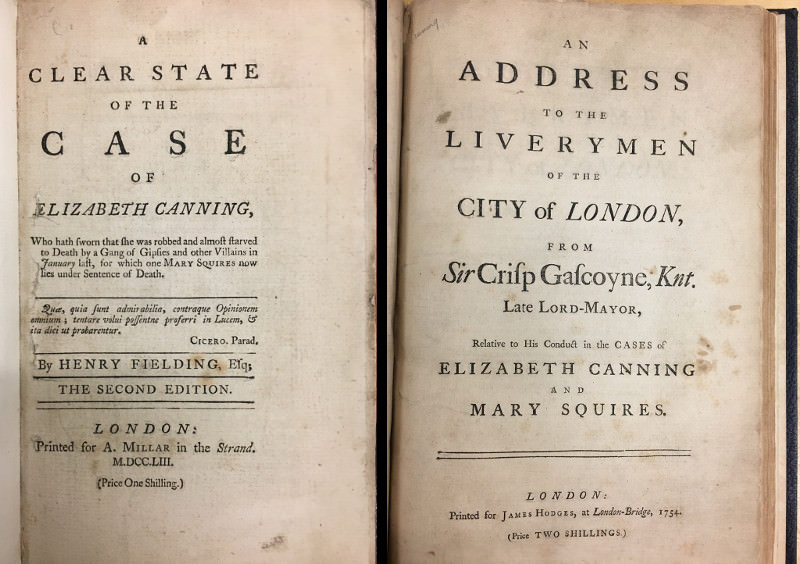

The archives and the focus on scandal forced my students to grapple directly with this openness but also to rely on their classmates to build a new network of knowledge. For example, the first scandal we investigated followed the archived media flurry surrounding the disappearance of an 18-year-old servant, Elizabeth Canning, in London in January 1753. Despite the hundreds of witness statements, thousands of pages of speculation, and incredibly detailed court documents, there is no authoritative document revealing the truth of what happened to Canning during the 28 days she was missing. Working in teams, students shared responsibility for the hundreds of pages of texts on the event. Yet, even with the accumulation of information, my students noted that their sources required them to read with a critical and active eye to determine what was important. Such analysis was built through collaboration as each group had to work together to create meaning—filling in factual background for their peers but also offering theories of how best to understand the event.

Figure 1. Students encounter a carefully preserved edition of Henry Fielding’s treatise supporting Elizabeth Canning as well as Crisp Gascoyne’s defense of Mary Squires. (Image courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library/University of Georgia Libraries.)

In addition to researching the scandal, the students were asked to inhabit the texts, taking on the roles of Canning supporters, defenders of the accused Mary Squires, or undecided “jury” members. Borrowing from the Reacting to the Past model, students searched the documents to find evidence and viewpoints that would cast doubt or bolster Canning’s story. Because of the breadth of the archive, group members were forced to collaborate, sharing information and determining a “narrative” of the event or, in the jury’s case, questions about the most puzzling parts of the evidence. This research culminated in a day of gossip as the Canning and Squire supporters attempted to sway the jury. The exercise asked students to take control of the archives and experience the scandal. Ultimately, students reported feeling overwhelmed by the ways archives pushed them to decide what was important in the reading and when their research was “finished” but such ownership of the work also inspired them to more and better research. Likewise, they were able to experience how the Canning scandal spiraled through the act of gossiping. The nature of scandal and the extensiveness of the archive resulted in a break in the pyramid structure of the classroom hierarchy and isolated writing; instead students built a network of information they then accessed in the process of creating new analyses of how the Canning event was reported.

Throughout the semester I repeatedly struggled with how to facilitate student interactions with the physical archive; however, student responses indicated that the physicality of the text was crucial because of its unique ways of provoking questions and revealing gaps in knowledge. Because the 60 total students could not all fit in the archives at the same time and because the archives had more limited access hours, my class used a combination of physical and digital archives, beginning in the special collections and moving into online replications or additions. While the blended method has significant logistical and access benefits, the students preferred their interactions with the hard texts. Looking at the online versions of 1913–1915 newspapers that covered the Leo Frank case, one student complained that the search functions “ruined” the research. The online versions cut out the surrounding articles to show only the searched-for material. The time in the archives, however, had shown the students that not all articles pertaining to the case mentioned Leo Frank but the extensive coverage would often give head-scratching in-depth coverage of a wide range of characters, such as the “Epps boy” who may or may not have seen Mary Phagan on a trolley or the long character pieces on the lawyers involved in the case. The search function, by taking over the investigation, limited the contextual range and sense of discovery the archives provided.

Figure 2. Image on left shows a full-page view of The Atlanta Constitution; image on right shows the screen view of a targeted search. The targeted search cut out three related articles. (Image courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library/University of Georgia Libraries.)

For each scandal, the students strove not just to understand the archives but also to comprehend the ways in which the archives interact with a larger sense of history and culture. The performative aspects of embodying the Canning case forced students to consider contemporary and historical values. Likewise, the class read and created adaptations to continue these discussions. We read a 1947 novel adaptation of the Canning case—Josephine Tey’s The Franchise Affair—and a 1937 film adaptation of the Frank case: Mervyn LeRoy’s They Won’t Forget. In working with these adaptations, students were able to note how each creator approached the archive; Tey shared an anxiety about young women’s sexuality with the original Squires supporters while LeRoy worried about the impartiality of Southern courts as did the northern journalists covering the Frank case. From these adaptations, the students recognized the importance of perspective and audience and the weight that interpretive power can have on the present. They, too, were asked to perform this curation of the archive—creating their own adaptation of one of the scandals. Throughout the semester, the students were asked to remix or immerse themselves into the scandals; in doing so, they engaged in deeper levels of analysis and application in their writing.

Reeves’s ENGL 1102: “Aliens in the Archives” in First-Year Composition II

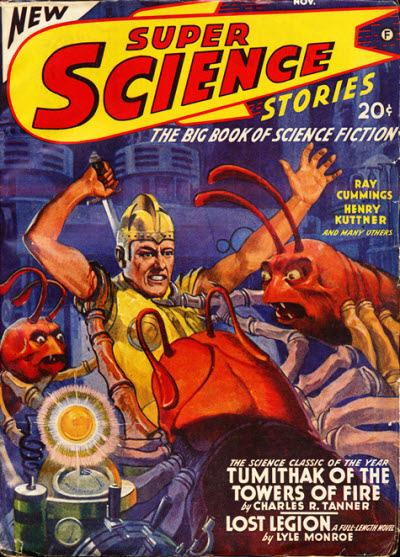

My objective was to show students the collaborative and symbiotic nature of writing, how composition begets composition, and encourage students to become not just consumers but also active members of writing communities. To do this, I turned to the Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Collection and its store of pulp magazines and apazines. Pulp magazines proliferated in the first half of the 20th century and were made up of genre fiction printed on cheap wood pulp paper. In these circulations science-fiction fan culture started. Like all fan cultures, community was a key component, and in this community, the written word became a means of connection. Fans started out writing letters to the editors, then moved to writing letters to each other based on the published fan letters, and graduated to the creation of apazines. Apazines, or amateur press association magazines, are handmade magazines with parts written by individual members, which are then sent to a predetermined editor, who collates the entries and then mails the completed apazine out to members. Science-fiction apazines became an important way for fans and budding fiction writers to communicate about their favorite authors and pulps, plan fan conventions, and make personal and professional connections. Ultimately, the pulps and magazines offer students the chance to look beyond academia and see how composition has shaped culture and how they might join such conversations.

Figure 3. This issue of Super Science Stories, November 1941, is of particular interest to my students as it includes the first story renowned author Ray Bradbury was paid for. (Image courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library/University of Georgia Libraries.)

This science fiction fan community and its connections between pulps, apazines, and authors was new territory for my students. As this contextual investigation is not the focus of FYC, I curated my students’ archive visits. Prior to our first visit, I divided students into six groups, with each focusing on a specific pulp writer. When they arrived at the library, the pulps that contained their author’s writing were waiting for them. For this first visit I had them focus on the pulp as an item. They examined the construction, paper and font type, use of color and art, and type and placement of ads. As a group they analyzed what these elements told them about the time period in which the pulp had been published and the intended audience. Such close interaction with the materiality of the text disrupted students’ conceptions of “acceptable” writing communities and forms, providing a clear example of how writing communities create their own ethos and voice.

This wide-ranging first visit was coupled with an in-depth read of a full pulp. The students returned to the reading room on their own and read their pulp from cover to cover in preparation for two short papers: a starred review of the pulp and an analysis of the part their pulp played in building a writing community. Before they began this second paper they were introduced to the libraries’ apazine collection. As Hayden (2015, 421) notes, one way to include the productive pedagogy of the archive in first year composition courses is through “smaller-scale projects … [involving] primary research or work with particular documents or collections.” As with the first visit, I curated their interaction with the apazines, so they would be looking at issues that had connections to their pulp. Both the apazine and the pulp collections have thousands of entries and no guiding information. While the possibility of not finding what you are searching for is an important part of archive learning, the goal of this class is to improve student writing through the archives—being able to navigate the archives is secondary. To do otherwise at this level and with these time constraints would result in students’ frustration, failure, and resentment toward the archives and composition.

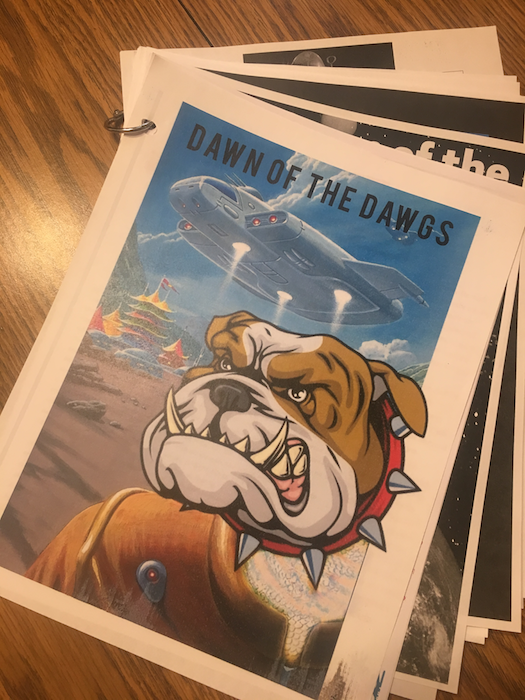

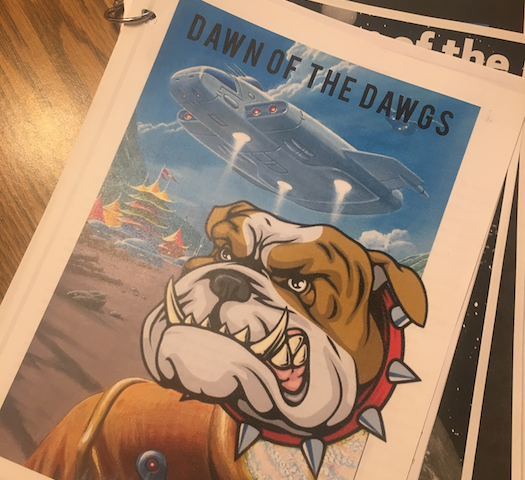

After the short papers were completed, students made two collaborative apazines and engaged directly in the communal process observed in the archives. The first apazine was made up of responses to archive resources. As a class, students drafted the rules of their apazine (i.e., entries can’t be over 500 words; Courier font only; graphics required), designed cover art, and voted on a title. Each student then revised one of their earlier papers, which became their apazine contribution. On the due date, each student brought 22 copies of their entry to class, which were then collated, and each student received a hard copy of the class apazine. The rest of class period was then spent in reading and conversation about the apazine. The second apazine was composed of responses to and interactions with their peers’ apazine writing. A student might write a response to a review of a story they hated but their peer loved, express admiration for a well-analyzed connection, or build on the research started by a peer. Each student entry had to be in conversation with an entry from the first apazine. In this way students were not just consumers of archival material but were producing writing that will itself be archived—at the end of semester, the apazines were donated to the University of Georgia’s Lamar Dodd Art Library. By making their own network of connected writing, students were able to experience the social nature of writing and produce a new archive of zine art.

Figure 4. Finished class apazine. The title, “Dawn of the Dawgs,” is an amalgamation of science fiction and University of Georgia culture.

Davis’s ENGL 4832W: “Rare Books and Book Technology” in Writing for the World Wide Web

The relevance of archival research for many of the upper-level writing courses I teach was clear from the start of my time as an archival Teaching Fellow, but the course that I ultimately structured around a major archival research component was Writing for the World Wide Web. Writing for the web is not simply about content creation. I have to prepare students for a future in which machines join us as readers and writers in networks, engaging in processes of pattern recognition. Writing for the Web has to focus not just on content production but also on how to work with and against algorithms, software, data, and metadata, as well as helping digital media authors understand themselves as participants in a network of distributed cognition.

The Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Collection presented a wealth of material that would intersect nicely with one of our texts, Naomi Baron’s Words Onscreen: The Fate of Reading in a Digital World. My goal was to foreground the problem of writing for online readers—readers who, as Baron’s research indicates, aren’t so much reading as scanning, skimming, and clicking quickly away to the newest, the now-est, the next. I focused on this problem of “not-reading” (or, in web lingo, TL;DR) in this course as the major design problem for writers in the digital age to solve, a problem that will, if we do not think carefully and critically about how to foster effective reading onscreen, have significant consequences for literacy and knowledge. In past semesters, I have drawn extensively on Murray’s conception of the “Four Affordances” of digital media to foster a design thinking approach to digital textual composition. In this course, I put Murray and Baron’s ideas into conversation with the history of the book as a material object in hopes of creating productive thinking about digital textual design. In addition to Baron’s text, I included Nicole Howard’s The Book: The Life Story of a Technology, in order to provide students with an accessible history of the book and to emphasize the connection between technologies of reading and writing. This combination provided the framework for an examination of the examples of book technology and its evolution contained within UGA’s Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Collection. Essentially, the course would foreground the way technologies enable particular kinds of textual production which, in turn, produce particular kinds of reading and writing practices—practices that ultimately have wide-ranging cultural effects.

I developed a design project that asked students to use rare books from the collection as inspiration for an innovative digital textual design concept. The Hargrett holds a wide range of texts—everything from early print incunabula to conceptual artists’ books—that would require them to reconsider their understanding of what a book is, as well as the kind of literacy practices that different types of texts cultivate. The project involved several components including a depiction of the text’s design (visuals, description/explanation, written manuscript of text); an analysis of how the design plan remediated features of the inspiration text and drew on digital media affordances; and a critical reflection on their design process. Additionally, we needed to connect the dots between the inspiration texts from the archive. To achieve that aim, we created a digital exhibit using Omeka, not only because it allowed us to create a public-facing product, but also because it introduced students to metadata, both conceptually and practically. Collectively “curating” and framing an exhibit of the archival material and working with the common vocabulary of Dublin Core Metadata standards would give us a final collaborative project to present to the Special Collections Library faculty as well as other interested faculty members and students.

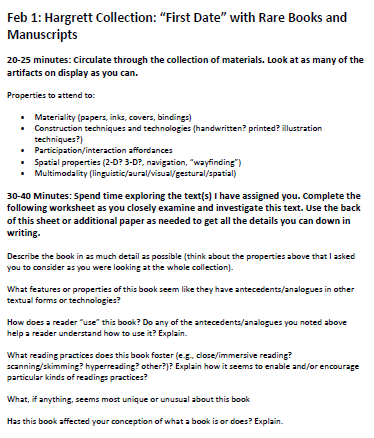

My own work as an instructor consisted largely of facilitation and research: I searched the archives, in consultation with a Hargrett librarian, for an initial collection of material that would represent a range of rare book items. On our first visit to the library, I gave each student an item to review along with a worksheet that asked them to consider several questions about the material aspects of the book they were examining and how it fostered or constrained different kinds of reading practices.

Figure 5. The prompt worksheet for Spring 2018 Writing for the Web students’ first visit to the Special Collections Library, asking them to explore and consider material properties and reading practices as they examine rare book items from the Hargrett Collection.

For our second visit, I asked students to tell me the kinds of texts they found most interesting from our first visit and, additionally, to provide an initial idea for their project that would help guide our archivist and me in curating a second collection of material for another round of hands-on exploration. We provided students with a tutorial on how to search the Hargrett collection themselves so that they could request additional material for viewing on their own. We also visited the Digital Arts Library Project, a collection of “legacy computers and video game systems as well as a collection of electronic literature pieces, digital interactive narrative pieces, and video games” (Digital Humanities, n.d.), and a copy of Raymond Queneau’s (1961) Cent mille milliards de poemes, a print precursor of digital media’s procedural affordance. Eventually, each student found a rare book (or two) that served as the primary inspiration for their design concept and they were each responsible for entering the information about the book (along with their own images taken during their time with the book at the library) into the Omeka site I set up at my web domain (having given each of them contributor access). For that exhibit, I also worked with the students to develop a conceptual frame for the project that would ground the exhibit in the concepts and scholarship that we were working with throughout the semester and, on the last day of class, we presented our work to an audience of interested colleagues. The event gave students a chance to engage in dialogue about their ideas and design process.

Figure 6. The collaboratively-produced promotional flyer for Writing for the Web’s end-of-semester exhibit of the design concepts inspired by rare book material.

Discussion

Our experiences suggest that archival work in the writing classroom facilitates greater interaction between the material properties of written texts and the students, while fostering collaborative curation. These collaborations add to or create new collections that are, in a sense, adaptations of the original archives. Reframing archival material in these ways makes new connections or linkages between seemingly disparate materials and reinforces the social and networked nature of knowledge production and a re-conception of how to use source material for remixing and remaking.

While our courses took us in diverse directions in terms of archival material and foci, the materiality of the archival texts played a large role early on for all of us. Pulps are characterized by colorful, larger-than-life covers that demand attention, as do the daring conceptual artists’ books and texts produced during the early days of printing press technology. These texts forced the students to reconsider how materiality affects reading practices. More eye-catching in a different way, the postcard that depicted Leo Frank’s lynching put students in physical contact with brutal history. This type of active learning pushes students outside their comfort zone and puts them in situations that require them to consider class content and apply that thinking toward course goals and their lives. Students began to see themselves as “scholar adventurers blowing dust off documents that could contain mysteries, answers, or maps of the past” (Norcia 2008, 107). It’s clear this technique relies heavily on critical and analytical thinking, which in turn improves and fosters strong writing skills (Bernstein and Greenhoot 2014; Gingerich et al. 2014). Perhaps even more important, it exposes students to a whole new world of composition. The inclusion of apazines, letters, and art projects in the archives showed students the legitimacy and value of such unconventional writing.

As each class progressed, students used the skills gained from archival research to recalibrate and restructure composition. Working with a physical text, as Kara Poe Alexander (2013) found when she incorporated scrapbooking into her first-year writing course, teaches “students the concept of affordance and demonstrates to them how materiality impacts design, composition, and rhetorical choices; it also provides a low-key, low-stakes entry into multimodal composing and reflexivity on the rhetorical decision making process.” A material example of the mingling of words and art/bookcraft gave students the tools they needed to compose their own multimodal projects and move from the page to the screen, without losing what made the original art projects unique. While Reeves’s students took advantage of the do-it-yourself nature of zines to produce their own, Davis’s students were unable to actually produce the digital texts they designed, lacking the advanced programming and coding skills necessary to bring those conceptual plans to life. This foregrounds again the social and collaborative nature of digital textual composition in which skilled programmers and visual artists might be required to actually produce an interactive digital text, just as a community of specialized craftsmen was needed to produce early print texts.

Ultimately, through both research and writing, the insistence on a more open, flexible network of knowledge remained key. This is perhaps best illustrated through one of the texts that several students in Writing for the Web found particularly compelling—a copy of Queneau’s (1961) Cent mille milliards de poemes. This mid-twentieth century precursor to the digital hypertext demonstrated the way that a single text can be remixed and reconfigured to provide an interactive experience for readers. That concept of interactivity became a key goal for Davis’s students’ design projects as they discussed the ways that the rare book material from the archives provoked a sense of pleasure in discovery and exploration. Janet Murray identifies this kind of pleasure in the text as an effect of careful design in her definition of the Procedural Affordance of digital media: “Procedurality and participation are the affordances that create interactivity and visible procedurality combined with transparent participation creates the experience of agency for the interactor, a key design goal for any digital artifact” (n.d.). In each of our classes, the experience of working with archival materials provided an experience not unlike that of “reading” Queneau’s text in which the ability to recombine and reconfigure the sonnets results in a sense of endless possibility for construction and reconstruction of meaning.

In her argument for “textual curation” as a unique “category of compositional craft,” Krista Kennedy cites Johndan Johnson-Eilola’s (2005, 134) contention that “Creativity is no longer the production of original texts, but the ability to gather, filter, rearrange, and construct new texts” (quoted in Kennedy 2016, 176). As in the Pop-Up Archives Project Jenny Rice and Jeff Rice facilitated at the University of Kentucky, our students curated experiences of archival material whose goals were “neither preservation nor a totalizing narrative” (2015, 247), but recontextualizations that, as in the conception of curation in the art world, put forward new arguments. Thoughtful curation requires immersion into larger conversations about issues and discernment about what is relevant and important in order to generate further discussion by “customiz[ing] archives toward their own ends” (Enoch and VanHaitsma 2015, 221). This year our students created their own handmade apazines, designed concepts for interactive digital texts, and performed reenactments of historical scandals. In each instance, they were asked to use historical materials throughout the compositional process, from the starting point of invention, all the way to the delivery of their ideas through curated performance, exhibits, and portfolios that present new understanding or expose new lines of inquiry.

We have come to consider archives-centered writing instruction as a pedagogy of remix, curation, and appropriation in which students are faced with a set of materials that may be vast and yet incomplete—an archive filled with gaps and unanswered questions that, like Queneau’s sonnets, can overwhelm with a sense of infinite possibility and insistent lack of closure. As scholars of digital culture have long insisted, remix is the foundation of knowledge construction and creative production. We each asked our students to discover ideas and compose new texts through a communal process of appropriation and reconfiguration that resulted in an awareness of what Neal Lerner (2010) has framed as the incompleteness of histories (203) and in, we hope, a reconsideration of what writing and textual form mean in the 21st century digital age. For student writers, exploring a variety of historical texts can decenter their conception of what constitutes writing or textual form, as Wells (2002) notes when she claims that “[a]rchival study of other kinds of texts also broadens our own sense of how difficult it is to write in new and untried ways” (59–60). That awareness is critical as we continue to chart the waters of digital writing at this particular technological moment. Digging into the past, we find in the archive a pedagogy well-suited to the future of writing.

'From Page to Screen and Back Again: Archives-Centered Pedagogy for the 21st Century Writing Classroom' has 2 comments

August 24, 2020 @ 4:37 pm Teaching With Digital Archives in the First-Year Writing Classroom – University Rating

[…] in my course was guided by a few questions: What can digital archives teach my students about writing? How can the study of digital archives advance the understanding of my students about borders and […]

April 29, 2020 @ 11:25 pm Teaching with Digital Archives in the First Year Writing Classroom | Studently

[…] in my course was guided by a few questions: What can digital archives teach my students about writing? How can the study of digital archives advance the understanding of my students about borders and […]