I have occasionally paid attention to the gamification literature, but this teaching challenge led me to revisit it. Serious about gamifying my classes for Spring 2018, I looked more closely at some practical advice and reports on gamifying, particularly within English. What I found were two overlapping approaches: gamification and game-based learning. With gamification, one establishes Experience Points (XPs), badges/levels, and, often, leaderboards. Game-based learning typically embeds learning within game-like structures. Much of what I have read emphasizes the merits of linking XPs and levels to game play.

I wanted more of my students to invest in the day-to-day work of the course by making more visible the contributions that homework, attendance, in-class work, and the formal writing assignments made to their grades by visibly rewarding productive behavior each day—and over time.

Gamified Basic Writing

I went “all in” on gamification for Spring 2018. I borrowed heavily from ideas in Tanya Sasser’s (2015) blog “Remixing College English” and John Hardison’s (2013) “22 Power Cards to Revolutionize a Class Discussion,” in addition to the idea of “coopertition” (cooperation within competition) that I learned about from my youngest child’s experiences with FIRST LEGO League. In keeping with the recommended practice in a gamified learning environment, I worked out an achievement constellation that linked learning outcomes levels to Experience Points (XPs) and that included bonus badges with XPs.

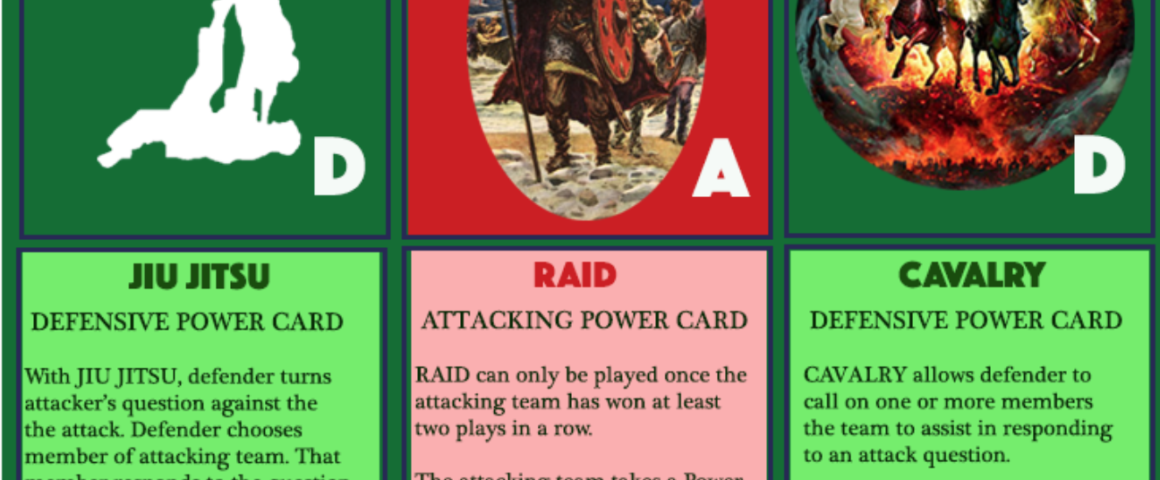

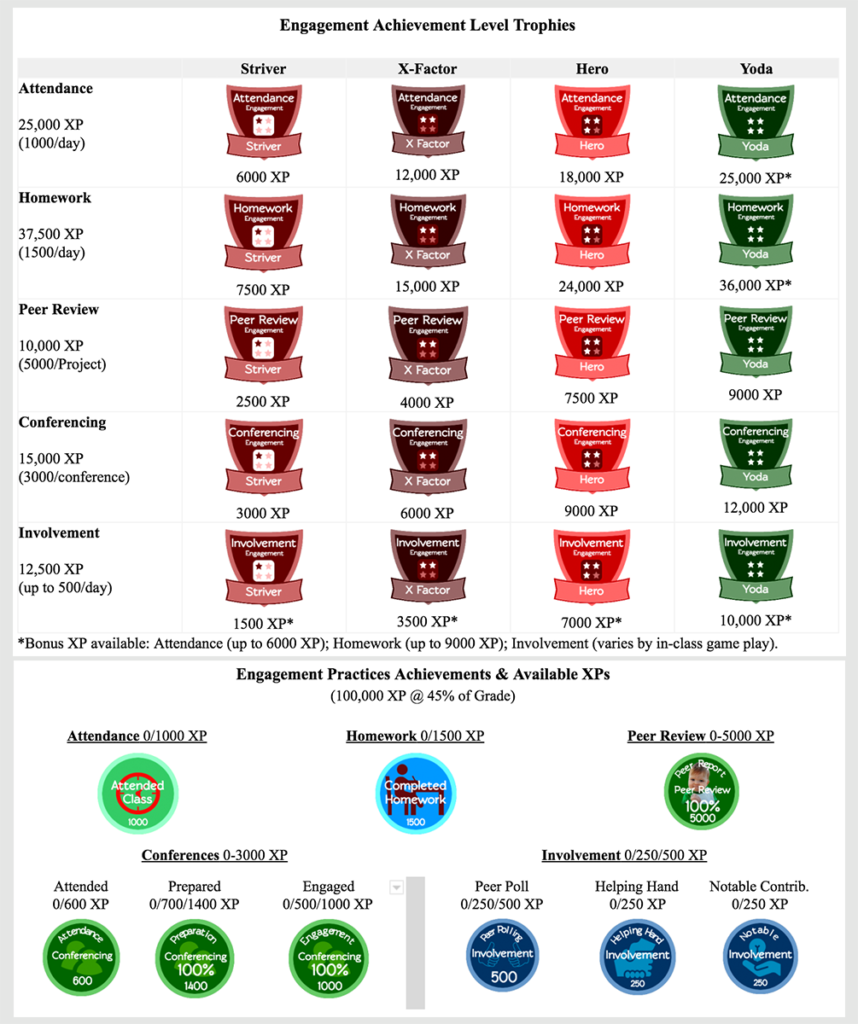

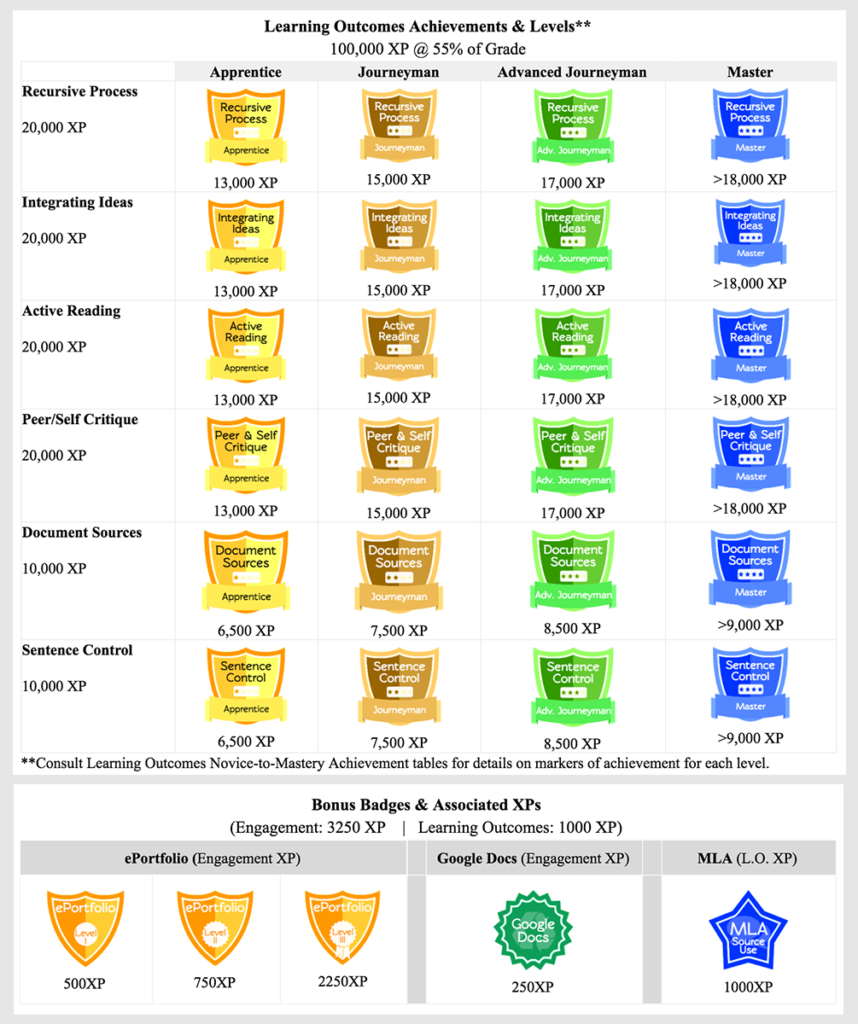

Also following recommended approaches, our XP numbers were big: 100,000 XPs for Class Engagement, 100,000 XPs for Learning Outcomes, and nearly 20,000 in possible Bonus XPs for a range of activities. I developed nine Attack and Defense playing cards (Figure 1) for team-based discussions (battles) to encourage productive, cooperative competition and inject “fun” into the work. In addition to regular in-class Involvement XPs, game-based play could earn students extra Involvement XPs. And I packaged each major paper in the course as part of a larger mission that involved publishing an edited collection organized around the topics we engaged in our readings.

Our “Achievements & Badging Constellation” awarded Engagement XPs for Attendance, Homework, and in-class Involvement, as well as Peer Review and Conferencing (Figures 2 and 3). Both Engagement XPs and Learning Outcomes XPs were linked to grades in the course. Each component in Engagement contributed to the overall Engagement XPs, which counted for 45% of the course grade. 80,000 Engagement XPs translated to an 80 (B-) in engagement. Learning outcomes were similarly broken up, and the 100,000 Outcomes XPs counted for 55% of the overall grade.

The achievement constellation established clear pathways to level up as students accumulated XPs in different categories. Starting the class as Noobs (a game term for a novice or newbie), students could quickly level up and move through Striver, X-Factor, and Hero levels before potentially earning Yoda status. The constellation even defined course learning outcomes in terms of levels (Novice, Journeyman, Advanced Journeyman, Master), with XP allocations to match. These levels were aligned with rubrics that defined elements of performance at each level.

To keep the earning visible, each class meeting began with students “claiming” earned achievements: 1,000 Attendance XPs if present and 1,500 Homework XPs if their homework was submitted. Each class ended with 2–3 minutes for students to complete an Attendance and Involvement card (Figure 4). The card served as a second check on Attendance in the event of a technical issue in the LMS and, more importantly, a tool for students to claim Involvement points or to propose them for peers. Students could nominate themselves if they made a notable contribution, nominate a peer for “helping hand” points if the peer was especially helpful, and nominate up to three peers for making notable contributions in class. Students were encouraged to own their involvement and to recognize peers’ involvement. Between class meetings, I reviewed submissions and awarded earned achievements in the LMS.

Teaching Fail #1

Most students quickly grasped much of the constellation, but too many seemed unmotivated by the potential to earn XPs. Most troubling for me were unclaimed Attendance and Homework XPs. I was certain that the visibility of XP earning at the start of class, coupled with the experience of periodic announcements that some students had leveled up, would encourage students to earn these basic XPs. Rather than mark students down for absences, I was awarding points when they showed up! Rather than assume homework would be done and mark students down when it was not, gamifying flipped it and made more visible the contributions that work made to the grade. However, the system did not magically improve attendance or homework completion, two basic prerequisites for success in any college class setting.

XPs were not an epic fail. Some students reported enjoying earning XPs, and the thrill of leveling up activated their competitive nature. One student, a Star Wars fan who quickly got my Yoda badge humor, requested a Sith Lord badge instead. When she leveled up to Yoda status, I made Sith Lord badges and awarded them to her, and a second student asked for the same when he leveled up. Others saw the constellation and points as a juvenile and unnecessary motivator. And other students reported that it was good to “know where you stand” on points in any category. Of course, regular grading/evaluation does that without requiring a new system of evaluation that students then need to learn.

XPs were not a big success. Not enough students altered their behavior. I did not design a study of gamification, but my sense is that the gamified class may have shifted 15% of my students marginally in the desired direction on Engagement factors. That’s something. But given the amount of recordkeeping and the time invested in building out the constellation and creating dozens of badges, I hoped for homework completion or attendance rates much more in line with those I see in other courses. Measured in this way, the gamified model did not achieve my goals.

Teaching Fail #2

I thought a gamified class required game-based play in some class sessions. I invented active reading battles, mocked up source selection games, and imagined a potluck group of sentence combining and source integration games I called “X-apalooza.” My students were mostly ready to take the journey with me. They tried to play!

Active, critical reading games typically involved teams of students preparing interpretations of ideas in our texts, making arguments for or against an idea, and challenging each other with competing textual evidence. Winners earned points in each round; overall winners earned game play XPs that added to each team member’s overall Involvement XP tallies. Group discussion games involved practice “passing an idea around” by picking up on a comment and responding by agreeing (with an addition), by challenging (with evidence), or by extending in a new direction (with more textual evidence).

In the action, students regularly forgot to throw the possible Attack and Defense cards (Figure 1) as they engaged in authentic conversation. Team back-and-forth got heated as competition put XPs at risk, but my official rules of the games inhibited a more free-form involvement, and the cards were just another thing to figure out in order to do the work of learning in the writing class. We didn’t need playing cards with provocative actions like Jiu Jitsu, Raid, or Grenade to work together, or to challenge peers. Within a couple weeks, we abandoned playing cards because they got in the way of the content: discussion of readings, sharing of draft ideas, examination of annotations, and more.

We retained modified team-based competitive activities and regularly had energetic interactions. We modified rules when it made sense to do so. Winners still earned bonus Involvement game play XPs. Even without XPs, though, I think the team-based competitions that encouraged sharing, challenging, and defending improved the energy in the room—and perhaps the learning.

One game I came to enjoy was the annotation battle. We worked on categorizing our annotations in the readings to build a greater awareness of the ways active readers mark texts. They make notes to understand, to ask questions of the text, to draw relationships (to self, to world, to text), and to challenge ideas in the texts. We used codes to name annotations—Understand, Question, Relate, Challenge—and new reading homework required annotating and coding annotations. Teams would review their annotations to prepare, make decisions about annotations to present, and share them in game play. Other teams would engage with the annotation, the relevant passage in the text, and the proposed code. They earned points by finding problems or by extending the idea in the annotation. The presenting team earned points for a solid presentation or a strong counter to a challenge.

Students who might have been more content to sit silently practiced advancing ideas, probing peers’ interpretations and offering textual evidence as a key component of the work. They were in the spotlight, playing for their team, helping a teammate, and trying to outdo another team. In-class coopertition, possibly coupled with in-class Involvement XPs, was moderately successful.

Teaching Fail #3

Uneven homework completion quickly put our timeline for the first mission in jeopardy. I was sure that publishing a “book” of student texts would motivate, but not all students had bought into the mission. (I do not know that any really did!) I quickly had to decide whether to abandon the broader goal of publishing an edited collection of our work. Pushing a death march to mission completion would put hard-working students’ performance partly in the hands of peers who were proving to be less than reliable teammates. We abandoned the broader mission concept to focus more on individual writing and practice engaging in class discussions. We made the right choice. In hindsight, I think that a formal, finished paper might function as a kind of mission in a gamified writing course.

Final Thoughts

While gamification is still fairly “hot” right now, the scholarship is actually mixed, likely because the mechanisms are quite complex. Some report ways that XPs, badges, and levels can enhance learning and motivate learners. Dicheva et al. (2015), in a review of 34 articles on gamification, find that most studies articulate a belief that well-designed gamification can improve learning. Ultimately, though, they find limited empirical evidence of positive effects on learning and claim that the impact on learning “remains to be demonstrated in practice” (Dicheva et al. 2015, 83). They call for more systematic empirical studies of elements of game systems. Subhash and Cudney (2018), in another review of the literature, observe that studies often identify “improved engagement, motivation, and attitudes” as key benefits of the gamification approach (197).

But improved motivation may be difficult to get—and sustain—via gamification. Hanus and Fox (2015), in a longitudinal study of relationships among motivation, effort, and performance in communications courses, explore the relationship between reward systems and both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. They draw on cognitive theory that suggests possible negative relationships between rewards like XPs or badges and intrinsic motivation, with possibly negative effects on learning outcomes. Results from their controlled study reveal that the badges, leaderboards, and game-based competitive play in a gamified course were associated with reduced intrinsic motivation and lower exam performance relative to a control course.

I was attempting to combat low intrinsic interest through a combination of game-like activities and XPs and levels. Where I might have preferred intrinsic motivation, I turned to gamification and a points model to motivate behavior more than attitude. I did hope that our missions and in-class games might prove fun in ways that could be interesting, and I observed generally positive attitudes toward classwork, some positive movement in desirable behaviors, and learning. Game-like structures in class likely aided some of that movement, and for some students the XPs and levels were motivators.

Intrinsic motivation might best be addressed by means other than gamification. In the writing class, this might involve a choice of reading or writing topics. Two-thirds of the way through the classes, after we had built a reservoir of community capital, I offered students just this option: We could continue on the path outlined in the syllabus, or we could opt for a different set of writing assignments. The syllabus outlined one final significant paper project that would occupy the remainder of the term, and I proposed doing two paper projects that would move a bit more quickly, have the same feedback mechanisms, and invite more variety. We had a discussion and made a collective decision on a path forward with two projects. I offer no evidence that behaviors changed markedly following that decision, but we were on a journey we decided to take. At the end of the term, my students reported liking the projects we took on. In some respects, I suppose we settled on a kind of mission.

I’m not gamifying my writing classes this year. There are no XPs, no leveling up, and surely no playing cards. But the work I did to gamify classes last year has affected my teaching. I’m more attentive to the smaller moves that my students make, to the value of more regularized feedback, and to the building blocks of my in-class activities. As I reflect on my teaching fails with gamification, I can imagine myself sprinkling gamified elements back into the class. XPs and levels might seem juvenile for some. For others, though, they are tokens marking another homework assignment completed, another class attended, and another meaningful in-class contribution. If earning XPs and leveling up can change those behaviors at the margins, why not put those elements back into the course?

Bibliography

Dicheva, Darina, Christo Dichev, Gennady Agre, and Galia Angelova. 2015. “Gamification in Education: A Systematic Mapping Study.” International Forum of Educational Technology & Society 18, no. 3 (July): 75–88.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.18.3.75

FIRST LEGO League. 2018. “What is FIRST LEGO League?” Accessed August 17, 2018.

http://www.firstlegoleague.org/about-fll

Hanus, Michael D., and Jesse Fox. 2015. “Assessing the Effects of Gamification in the Classroom: A Longitudinal Study on Intrinsic Motivation, Social Comparison, Satisfaction, Effort, and Academic Performance.” Computers & Education 80 (September): 152–161.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.08.019

Hardison, John. 2013. “22 Power Cards to Revolutionize a Class Discussion.” Getting Smart (March). Accessed August 17, 2018.

http://www.gettingsmart.com/2013/03/22-power-cards-to-revolutionize-a-class-discussion/

Sasser, Tanya. 2015. Remixing College English. Accessed August 17, 2018.

https://remixingcollegeenglish.wordpress.com/

Subhash, Sujit, and Elizabeth A. Cudney. 2018. “Gamified Learning in Higher Education: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Computers in Human Behavior 87 (May): 192–206.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.028

'Gamification Fails: Negotiating Points, Badges, Levels, and Game Play in the Basic Writing Classroom' has 1 comment

November 2, 2020 @ 7:01 am 10 Bad Gamification Examples: Learning from Failed Projects – Keep Them Engaged

[…] found this example in an academic study here and thought that this one is certainly worth sharing. The summary is that a teacher has tried to […]