Jared S. Colton, Utah State University

Rebecca Walton, Utah State University

Abstract

Incorporating social justice concerns into the communication design classroom can be difficult. Based upon a pedagogical study, this article proposes that considerations of disability can provide insight into the relevance of social justice to technical communication practice. Engaging with notions of disability enables students to recognize the existence of privilege. This recognition better enables students to talk about what they might consider less comfortable facets of privilege (race, gender, class)—facets many of them have been taught to reject outright or view as an agenda in contradiction to their own personal value systems. Disability is not readily associated with any particular political position and thus can pave the way for consideration of other social justice topics.

Introduction

As the theme of social justice gains more traction in technical communication scholarship, instructors are trying to invent ways to incorporate ideas of social justice into their classrooms. Still, the relevance of social justice to technical communication is not readily apparent to everyone, perhaps least of all to students. To address this problem, this article proposes one strategy in which considerations of disability can provide insight into broader notions of social justice in the communication design classroom. The context for the research we present is a shift in the curriculum at our university to more centrally incorporate issues of social justice. To inform this curricular revision, we designed a pedagogical study (IRB approval #6070) to help better understand how to bring social justice pedagogy into the technical communication classroom. The broader overall study investigated three undergraduate course designs being piloted in the 2014-2015 academic year and involved multiple methods to collect data at various times throughout and immediately after the fall and spring semesters. This article homes in on one of those three courses (a course on rhetoric, digital media, and disability studies) to investigate the promise of disability studies for initiating students to the relevance of social justice to technical communication. Our findings demonstrate that facilitating students’ awareness of disability can serve as an entry point for helping students recognize the relevance of social justice to the work of communication design.

Technical Communication and Social Justice

Although the term “social justice” is only recently gaining prominence in technical communication scholarship (see Agboka 2013; Haas 2012; Leydens 2012; Walton and Jones 2013), the field has long been concerned with inclusivity and unjust power disparities, producing a sizable body of relevant scholarship. Social justice research in technical communication has been defined as “investigat[ing] how communication broadly defined can amplify the agency of oppressed people—those who are materially, socially, politically, and/or economically under-resourced” (Jones and Walton forthcoming). This research aligns with early technical communication scholarship positioning the field as humanistic (Miller 1979) and with scholarship from a critical-cultural turn, which began explicitly acknowledging concerns of power, hegemony, voice, culture, and diversity as relevant to the field (see Scott and Longo’s 2006 special issue of Technical Communication Quarterly and Herndl’s 2004 special issue of Journal of Business and Technical Communication). Extending this earlier work, social justice research moves beyond description and analysis to take action against oppression.

“Social action” is the term used by Rude (2009) to identify one of four major categories of technical communication research. This research takes a variety of forms: for example, service learning, in which students apply their developing expertise to support community and nonprofit organizations (e.g., Scott 2008; Youngblood and Mackiewicz 2013); community-based research, in which scholars partner with nonacademic communities to pursue issues of mutual interest for social good (e.g., Faber 2002; Walton, Zraly, and Mugengana 2015); action/activist research, which requires that nonacademic communities benefit from the knowledge produced and actions facilitated by research (e.g., Clark 2004; Grabill 2000); and civic engagement, which aims to improve public understanding of issues relevant to people’s lives (e.g., Bowdon 2004; Moore 2013). These forms are not always distinct but often overlap: service learning and civic engagement (e.g., Scott 2004), civic engagement and action research (e.g., Blythe, Grabill, and Riley 2008), action research and service learning (e.g., Crabtree and Sapp 2005).

Under the broader umbrella of social justice research, we characterize our project as service learning and action research. We provided students opportunities to practice their new skills to produce knowledge and facilitate action that benefits communities—specifically, people with disabilities in the Cache Valley area of Northern Utah. It was our aim that in so doing, students develop an ethical framework in the sense of a neo-Aristotelian virtue. While ethics is conceptualized and practiced in a variety of ways (e.g., duty, rights, care, utility), Aristotle considered ethics a systematic study of the character of good action. For Aristotle, ethics was not a scientific problem or a heuristic readily applied to any situation but rather a pursuit that was a reward unto itself. In other words, doing “the right thing” because it is “the right thing,” not because an action yields more favorable results or is simply an assigned responsibility. One of the key terms in Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics (2011) is “virtue,” which characterizes a person’s being rather than a particular act. In this framework one would not view a person as virtuous based upon one inclusive act or a statement such as “I believe in equality”; rather, a virtuous person’s ethical practices would appear to others as part of his or her character—not as instinct but as an element of a carefully cultivated disposition. This sense of ethics—as day-to-day practice, as beliefs enacted, repeated and continually improved upon—is where we see technical communication and social justice converge.

We admit that looking to Aristotle for a contemporary concern and concept of social justice may seem strange or antiquated to some, as Aristotle likely would not have recognized people with disabilities as citizens, and Aristotle’s moral virtues are those of citizens enlisted in political activity. Also, Aristotle’s virtue ethics are often thought of as individual virtues. How then, does drawing upon such a notion of ethics benefit technical communicators looking to engage in social justice? To the first point, contemporary virtue ethicists such as Garver (2006), MacIntyre (2007), and Vallor (2010) each have demonstrated that such repellent embarrassments (of racism, sexism, and able-ism) found in Aristotle’s writings are unethical to a contemporary neo-Aristotelian virtue ethics framework and that some of Aristotle’s absurd comments on ethical and unethical action (such as the notion that it is more virtuous for a city to open its gates to an enemy so that the battle is fair) are not constitutive of the theory of virtue itself. This theory of virtue in its simplest form is the idea that being good and doing good are intertwined. In other words, for Aristotle, virtues “that promote the agent’s self-realization” and “those that promote the good of others” are not separate (Garver 2006 p.5).

Ironically, the second concern, that virtue ethics are individualistic (which, of course, is not the same as individualism), is actually why virtue ethics are so helpful to technical communicators. Unlike contemporary theories of justice found in liberalism (Rawls 1971) and libertarianism (Nozick 2013), in which it is not the individual citizens who are able to enact social justice but only the state and its institutions (a position many students reinforced when first discussing social justice), a neo-Aristotelian virtue ethics sees justice as a learned disposition of one who does what is just situationally with respect to community values and who distributes good equitably in those contexts (trans. 2011 V.9). Rather than a framework that views enactments of social justice as occurring only when institutional mechanisms are adjusted by those in power—in which the most an individual can do is lobby for an injustice to be rectified—a virtue ethics framework considers justice a mode of being that is manifest through continual practice. This shift enables technical communication students to imagine practicing social justice even if they do not work for a non-profit organization or some other entity specifically organized around concerns of social justice.

Course Design

Listed as a topics course for technical communication majors, the focus was on rhetoric, digital media, and disability studies. In framing the course, Colton asked the students on the first day of class, in the spirit of Roman rhetorician Quintilian, “Is a good document designer also an ethical and just document designer?” The course learning objectives centered on enabling students to see all design practices as having an ethical component, an insight that would allow them to see their work as having effect on social justice. This latter concern was a significant challenge, as most if not all of the students had considered technical communication and social justice to be unrelated.

Required texts included Meloncon’s collection Rhetorical Accessability (2013a), Williams’s The Non-Designer’s Presentation Book (2010), and Davis’s The Disability Studies Reader (2013a). Rhetorical Accessability was key to bridging the gap between a basic presentation design book (Williams 2010), the kind of text to which the students were accustomed, and a critical theory book on disability studies (Davis 2013a). One of the major arguments the authors in Meloncon’s (2013a) collection make is that considering the needs of users with disabilities also makes one a better and more desirable technical communicator in general: i.e., accessible practice is effective practice, whether in terms of document design or pedagogy. As a case in point, Pass (2013) argues, “Effective accessible design doesn’t just help those with permanent disabilities—it helps everyone” (p. 118). Oswal and Hewett (2013) similarly state “the recommended alternatives and practices [toward accessibility] will help instructors improve their courses for all other students as well” (p. 151).

Through reading, discussing, and producing content in response to the chapters in Rhetorical Accessability (Meloncon 2013a), the students learned to consider various disabilities of potential users and strategies of writing for and with these users. For example, after reading Gutsell and Hulgin (2013), the students began changing their language practices—whether using people-first language or the type of language a particular community prefers (e.g., the “deaf community”), rather than relying solely upon medical sources, popular media, or the models of language with which they were familiar. Many students had never considered designing for people with autism and found Elmore’s (2013) discussion of the social construction of independence and dependence as challenging to their worldview, a worldview dominated by neo-liberal individualism. This chapter was a first step for many to begin seeing how all humans are interdependent and that labeling others as “disabled” is a product of our social institutions’ privileging of particular kinds of interdependence (namely white, male, abled, etc.). This notion of interdependence was especially powerful, and many students reiterated throughout the semester how recognizing different types of interdependence (including their own) gave them an ethical incentive to consider people with disabilities in their designs and communications.

Arduser’s (2013) chapter on the language of diabetic communities helped students recognize that the language one uses can empower, disempower, include, or exclude users, and that how one defines disability (Pass 2013) makes a great difference to the social institutions creating accommodation law and policy. Some students noted that under the right socially constructed circumstances and the right definition, they could be categorized as having disabilities themselves. Broadly considered, Rhetorical Accessability made more accessible some of the more theoretically and ideologically challenging material in Davis’s collection (2013a), which introduced the students to arguments and information such as problems of normalcy (Davis 2013b), the history of disability law (Emens 2013), institutional inequality (Baynton 2013), and invisible disabilities (Samuels 2013).

For the major assignment in the course, a service-learning project, Colton developed a relationship with the local Center for Persons with Disabilities (CPD). The students would video and caption CPD guest lectures (given by persons with a disability or loved ones affected by disability), then edit the videos by adding various b-roll footage, images, documents, and presentation slides in a manner that would fit the screencasting genre and would be suitable for online learning. To prepare the students for the final project and allow them to practice their video production and captioning skills in the context of the readings, the course was organized around two additional major assignments: reading reflections and an intervention assignment. The reading reflection assignment prompted students to summarize the disability studies and technical communication readings for the past two weeks (usually four articles) and respond to them, similar to a typical summary/response essay. Reading reflections early in the semester were in the form of a written essay; reading reflections later in the semester were in the form of a screencast. This format enabled students to practice their presentation design skills (such as Williams’s (2010) principles of clarity, relevance, animation, and plot), as well as practice their skills in captioning for significant sounds (Zdenek 2011) through the production of three-minute videos.

Inspired by and modeled after Zdenek’s own pedagogical practices,[1] the intervention assignment gave the students a chance to look for something in their own life that was inaccessible in some manner to a person with disabilities. For this assignment, some students continued to work on their captioning skills by uploading captions (via free online software such as Amara) to a YouTube video of their choice that had no captions or poor captions as a result of YouTube’s automatic-captioning algorithm. Other students chose to follow the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0 to edit the code and content of a website toward better worldwide accessibility (Lewthwaite and Swan 2013). These website interventions included writing alternate text for images and, where possible, revising the content on the site by creating linear reading paths, informative (rather than “cute”) titles and headings, and writing in plain language (Jarrett, Redish, and Summers 2013). Through these assignments, students engaged with concepts of rhetoric, digital media, and disability studies. This engagement proved productive in at least two ways: introducing concerns of social justice into the practice of technical communication and prompting reflection on social justice issues—even beyond concerns specific to disability studies.

Methods

The findings reported in this article address two of the broader study’s research questions:

- What are students’ perspectives on the relevance of social justice to their professional field? to their own professional goals?

- What factors were useful for fostering in students a critical reflection on social justice?

One type of data informing this article is anonymized student assignments: four reading reflections and an intervention assignment. This data addresses research question one by conveying student perspectives at multiple points throughout the semester and research question two by indicating whether and to what extent assignments prompted students to engage in critical reflection on social justice-related concepts. One limitation of this type of data stems from the rhetorical context of assignments: some students may say what they think a professor wants to hear in an effort to get a good grade. Another limitation is that this data alone is unlikely to uncover factors beyond readings and assignments that are useful for fostering critical reflection on social justice.

We engaged in several strategies to mitigate these limitations. First, Colton took care to create a supportive discussion environment (online and in person) in which students could share a range of perspectives. He intentionally asked open-ended questions, gave time and validation to different viewpoints, and asked students to do their best to avoid discriminatory language but also not police each other as they were learning new discourse practices regarding disability. A second strategy for mitigating limitations was to provide students with assignment descriptions and grading rubrics that explicitly focused on critical engagement (i.e., not on arguing a particular point or advocating for an instructor-selected position), and grading comments reinforced that focus on critical engagement, not on parroting a particular view. Third, we engaged in three types of triangulation to improve the rigor of the study and validity of the findings (Denzin 1978; Patton 1999):

- Sources: We analyzed several sets of data collected by the same method—for example, reading reflections produced by students at different points throughout the semester.

- Methods: Participants produced data through different methods—e.g., semi-structured interviews, written essays, and multimedia documents.

- Analyst: We engaged in iterative, joint data analysis to develop the coding scheme.

Students were informed of the study at the beginning of the semester, given opportunities to ask questions, and provided with an information sheet that detailed how they could opt out of the study (as well as other information, such as purpose, benefits, and risks of the study). Students could opt out at two levels: 1) removing only their individual assignments from the study and 2) removing any collaborative assignments to which they contributed. To minimize coercion, the opt-out procedure enabled students to withdraw at any time[2] without their instructor knowing until after grades were submitted. A university employee who was unaffiliated with the study agreed to collect any forms (which were attached to the information sheets provided to every student) and hold them until after grades were submitted, at which point the assignments of participating students could be anonymized for analysis.

Students were also invited to participate in a semi-structured interview after classes had finished meeting for the semester. To minimize coercion, Walton conducted all recruiting, scheduling, and interviewing without Colton’s involvement or knowledge of which students participated until after grades were submitted. This method provided a different rhetorical environment for data collection, in which participants could enact a greater degree of freedom in expressing their views (Moeller, Walton, and Price 2015). Interviews ranged from 30-45 minutes and addressed the following topics: a) students’ experiences and perceptions of the course, b) effects of the course on their perspective of social justice, c) effects of the course on their professional goals, d) effects of the course on their feelings of preparedness for entering their profession, and e) their own perceptions of their learning outcomes. No students opted out of the research study, and nine of the 20 students participated in an interview.

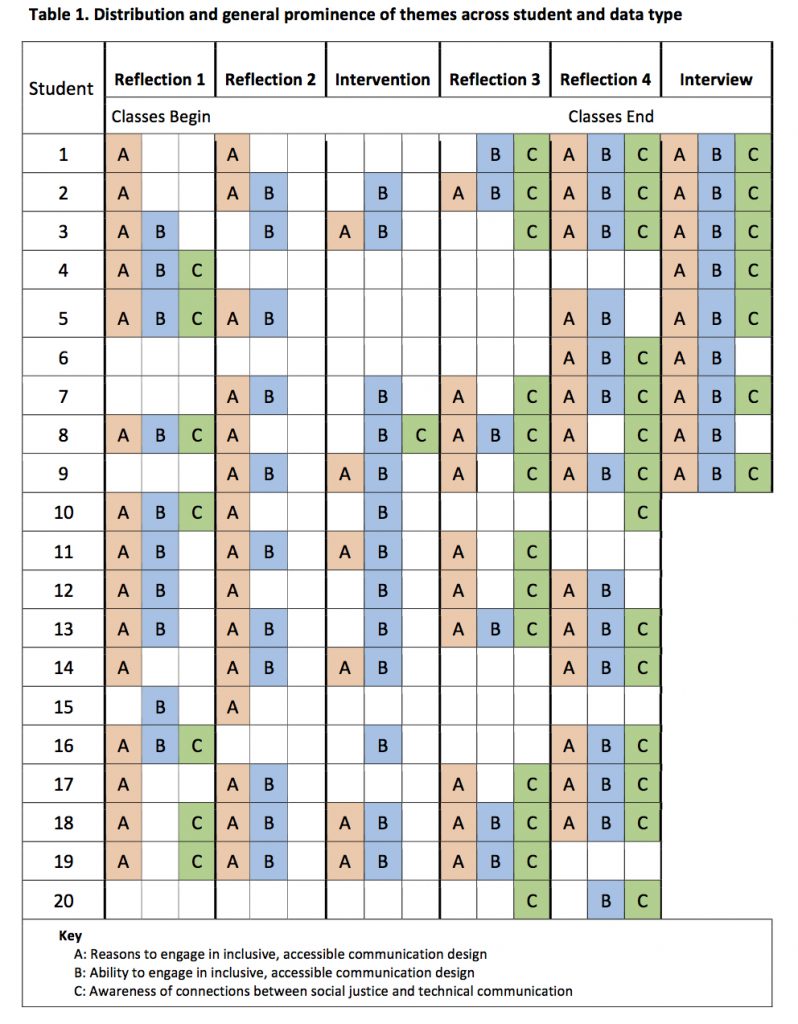

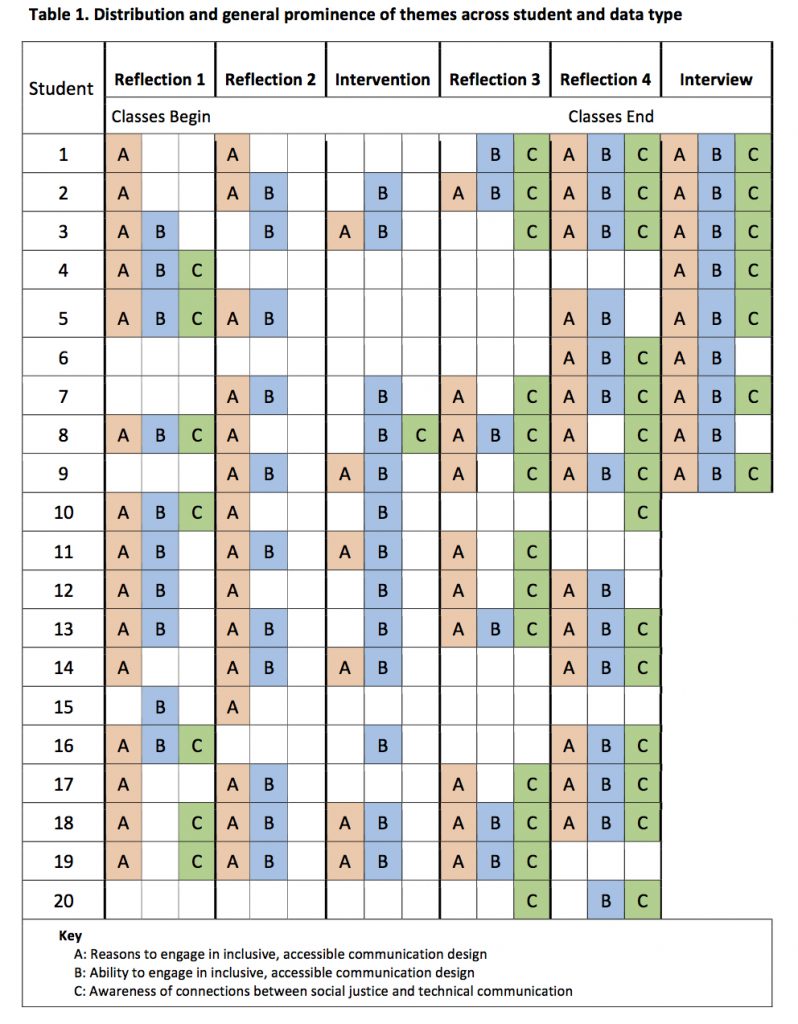

Findings were identified through iterative formal coding of interview transcripts and student assignments to identify patterns of meaning (Braun and Clark 2006; Miles and Huberman 1994 p. 55–69). In the first round of coding, Colton and Walton independently coded the same subset of data, noting all direct and indirect references to social justice, such as describing challenges faced by marginalized people and advocating accessible communication design. We created memos to note potential patterns and relationships among these patterns. Based on patterns we both saw emerging in the data, we iteratively developed and applied a joint coding scheme from which three themes emerged:

- Reasons to engage in inclusive, accessible communication design: being a more proficient and valuable technical communicator; doing what is ethical.

- Ability to engage in inclusive, accessible communication design by recognizing exclusionary practices and identifying ways to make communication more inclusive to people with disabilities, in terms of both usability and representation.

- Awareness of connections between social justice and technical communication beyond issues specific to disabilities.

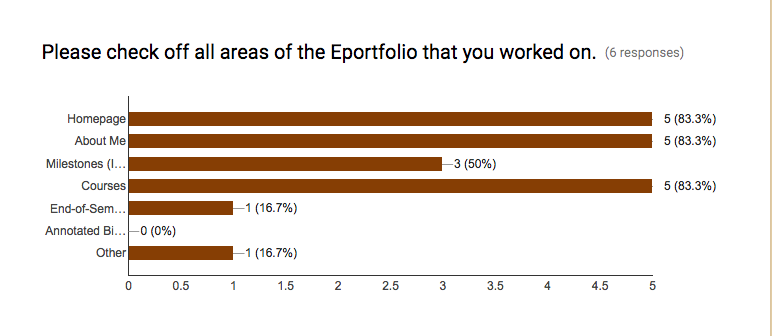

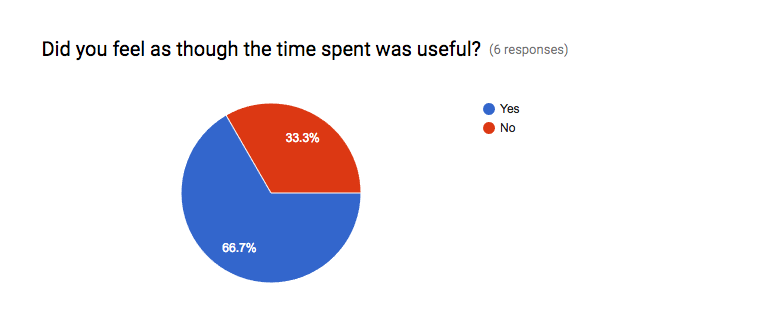

These themes emerged across multiple data types, across the semester, and across students. Table 1 below shows the distribution and general prominence of these themes. Each letter (A, B, C) indicates at least one application of a particular code according to data type and student.

Findings

Our findings suggest that facilitating students’ awareness of disability can serve as a productive entry point for helping students recognize the relevance of social justice to the work of communication design. The findings suggest how students can begin to revise their practices to reflect this change in perspective regarding the role of the field and their place within it.

Reasons to Engage in Inclusive, Accessible Communication Design

The first theme conveys patterns of students’ reasons to engage in inclusive, accessible communication design. The most immediate insight was that making design more accessible simply made them better technical communicators. This insight broadened their perceptions of the role of the technical communicator—e.g., whether as a web designer, a manual writer, or an editor—to include a consideration of all potential users, especially people with disabilities:

“As technical communicators, it is our job to write and communicate about these technologies. [. . .] However, because users’ technological embodiments aren’t all the same, documentation will not be all the same. It will require that we are adaptable to different users’ needs.” [Source: Reflection 1 in response to Meloncon (2013b)]

“It is our job as technical communicators to provide autism-friendly applications and programs through design principles, usability tests, and audience analyses.” [Source: Reflection 1 in response to Elmore (2013)]

In addition, students indicated that considering accessibility would make them a greater asset to employers or would provide them with cultural capital by setting themselves apart from others in the field of technical communication:

“As we create these user-centric documents, we will be aware of what we need to do to make them accessible in order to reach a more broad audience. By being able to reach a more variety of audience, we will become more valuable technical communicators.” [Source: Reflection 1 in response to Elmore (2013)]

“A more sound knowledge of people and disabilities would be very beneficial to me as a technical writer.” [Source: Reflection 1 in response to Elmore (2013); Jarrett, Redish, and Summers (2013); and Meloncon (2013b)]

Finally, beyond a consideration of accessibility making them better technical communicators, some students articulated a concern for ethics and social justice. Moving from a constitutive “this is what a technical communicator does” to a normative “this is what a technical communicator should do,” the students began to posit accessibility as more than just a job of the technical communicator; instead, communicating accessibly is also a means to express and enact an ethical value:

“It is important to be ethical in the workplace by not empowering stereotypes or social bias.” [Source: Reflection 3 in response to Davis (2013b)]

“People all have different problems, but some are just more visible than others. As we help make content accessible for everyone, we will understand our fellow human beings that much better.” [Source: Reflection 3 in response to Linton (1998)]

“It is not ethical to design for the abled while ignoring the disabled.” [Source: Reflection 1 in response to Meloncon (2013b)]

“The more technical communicators that are aware of these kinds of issues the more the industry in general will change. So, it’s the kind of thing that can snowball, and have a greater effect than even just on that particular classroom.” [Source: Interview]

The above quotes indicate that many students began identifying a concern for people with disabilities and for composing with accessibility as more than just an expanded role of the technical communicator. Students articulated ethical commitments exceeding their job descriptions, including the following: discrimination of people with disabilities is wrong; normalcy is dangerous; an appreciation of difference is important; technical communicators can create societal change; and the students themselves, alongside and by paying attention to people with disabilities, can be the instigators of this change.

Ability to Engage in Inclusive, Accessible Communication Design

The second theme involves students’ ability to recognize and engage in inclusive communication design: inclusive in the sense of being usable for people with disabilities and inclusive in the sense of being respectfully representative of people with disabilities. Regarding usability, students identified several examples of problematic design:

“Going from a simple search engine page to this sudden and immediate page full of visual images, links, and sounds can be overwhelming, even stressful.” [Source: Reflection 1 in response to Jarrett, Redish, and Summers (2013)]

“A few of the slides were completely covered in text, and because there was a lot of text, the text was small. This made the presentation difficult to read and hard to digest the information that was most vital.” [Source: Reflection 1, sharing a personal anecdote in response to Jarrett, Redish, and Summers (2013)]

“For low-literacy users, even locating the option for TTS [Kindle’s text-to-speech feature] could be an issue. There are several links at the top of the reading interface, and TTS is located under the settings link.” [Source: Reflection 1 in response to Jarrett, Redish, and Summers (2013)]

“Not captioning videos excludes people who cannot hear, have difficulty hearing, have difficulty processing aural input, and people who simply have a hard time understanding the speaker’s accent from enjoying the benefits of public videos.” [Source: Intervention assignment]

As demonstrated in the above quotes, students identified a range of examples of document type (e.g., online search site, slide presentation, ebook, online video) and of people being marginalized (e.g., people with cognitive differences, with sensory differences, and with low literacy in a particular language). Students recommended specific changes to improve inclusivity, such as fewer, more meaningful links and multiple representations of the same content, such as image, text, audio track, and closed captioning. Noting that no single design could ideally accommodate everyone, several students suggested recruiting people representing wide ranges and types of abilities to engage in user testing, and one student recommended creating multiple versions of the same document, each with full and equal content to avoid further marginalizing people.

Communication design was also described as exclusionary for problematic representations of marginalized groups. For example, after reading the following sentence on a local business’s homepage, “Almost anyone can bowl, even if you have a disability,” a student referenced Gutsell and Hulgin (2013), saying:

“By placing this on their website, the bowling alley has incorporated exclusionary language when their goal is to convey that they are inclusionary—their language is doing exactly the opposite of what they would like it to do by embracing the supercrip metaphor as an advertising tool.” [Source: Reflection 2 in response to Gutsell & Hulgin (2013)]

The most commonly described examples of problematic representations involved people with disabilities being used as a means to an end, such as advertising, fundraising, or winning political office. Students described these representations as exclusionary, noting that they dehumanize and misrepresent people with disabilities and their interests.

Though positive, we do not see the students’ design recommendations themselves as the primary contribution to social justice pedagogy but rather the change in student perspectives and awareness that these recommendations represent. In identifying examples of what makes communication design marginalizing versus empowering, students demonstrated the ability to take action, to engage in the inclusive practices that they had described as important to being proficient technical communicators and ethical people.

Several students described their subsequent efforts to make documentation more inclusive in the organizations where they work or volunteer, including a food pantry, a domestic abuse shelter, a local museum, and the college of natural resources. Other students emphasized the importance of pairing awareness and action:

“I felt like I had to just think on a personal level, like, how can I improve it? […] For example, saying, ‘We need to provide captions for videos,’ but then also having a tutorial video of how to provide captions. It’s all fine and great that people are aware of the situation, but if they don’t know how to resolve it, then it doesn’t really go anywhere. So there’s actually no social justice; it’s just an idea.” [Source: Interview]

Awareness of Connections between Social Justice and Technical Communication

The third theme provides evidence of students making connections to broader notions of social justice beyond disability. We see here a critical awareness of experiences of people who occupy positions of lesser privilege because of their gender, race, ethnicity, or sexuality, as well as ability. For example, in reflecting upon their readings, students engaged with notions of normalization and power, historical justifications for discrimination, and positionality as socially and culturally constructed. Students then began noting the relevance of these concepts to multiple marginalized groups:

“Linton [1998] states that disability was constructed to serve certain ends, specifically a compromised social position. Taking that further, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation are also socially constructed.” [Source: Reflection 4 in response to Linton (1998)]

“Baynton [2013] addresses the notion that labels, such as those for disabilities, are powerful weapons for inequality and are used to justify treating people differently.” [Source: Reflection 4 in response to Baynton (2013)]

“There are similarities between people with disabilities and an LGBT individual. It’s a personal decision to come out, whether as gay or having depression.” [Source: Reflection 4 in response to Samuels (2013)]

“Disability rights is very much like a civil rights issue.” [Source: Reflection 4 in response to Baynton (2013)]

“This idea of normalcy strives to make humans appear as closely related to one another as inhumanly possible: in behavior, dress and appearance, health, and intelligence, among many other aspects.” [Source: Reflection 3 in response to Davis (2013b)]

Noting the relevance of these concepts to multiple marginalized groups, some students became more attuned to issues of inequality in their day-to-day lives. This awareness led to empathy that could inform the decisions they make as communicators: for example, taking care to use people-first language and respecting the rights of people to name aspects of their own identity:

“I think I’m more aware of those around me and the automatic judgments that are passed, and things like that. So, I think that social justice and accessibility and all of that really played a role in how I view those around me.” [Source: Interview]

“It’s very important that we understand the definitions and terms [preferred by members of marginalized groups] but also understand, kinda, what they’re going through. Take a walk in their shoes.” [Source: Reflection 4 in response to Price (2013)]

We find this increased critical awareness particularly encouraging in light of students’ early perspectives on social justice. Students consistently described their views of social justice at the beginning of the semester as unrelated to their own lives and certainly to their profession, with many explaining either that they had never heard the term before or that they had vaguely related it to notions of picketing and protesting:

“Student: I didn’t think it [social justice] had anything to do with technical writing at all. I just thought it was people, like, campaigning for different things or fighting for different rights. [. . .] I had an idea it was doing the right thing, but I didn’t figure that was a big part of technical writing at all.

Interviewer: Did your perspective change over the course of the semester?

Student: One hundred percent. It was crazy. When I would create designs, I wouldn’t factor in different audiences. That’s the main thing. […] It just didn’t really factor into my designs. I felt like a really bad person after that, but I’m glad I took this class because now I know.” [Source: Interview]

We see this increased critical awareness—e.g., moving from vague notions of social justice to a commitment to consider marginalized audiences in one’s communication design—as a good start. But the complexity of understanding, commitment to righting unjust inequalities, and awareness of complicity varied across students. For example, Table 1 suggests student 20 did not embrace (or perhaps did not understand) these notions, even advocating for design strategies that were explicitly identified as oppressive in the readings:

“We can learn from these poster children in our own design. Creating something that is rhetorically pleasing and evokes emotion is the surefire way to grab people’s attention.” [Source: Reflection 4 in response to Longmore (2013)]

Also, while many students embraced people-first language, others resented what they saw as constraining political correctness:

“[Using people-first language] can be very important in emphasizing the fact that they’re a person first, but at the same time it can really grate on people sometimes, too, to have their vocabulary policed like that. And it can create negative feelings.” [Source: Interview]

As the above quote suggests, not all students saw social justice as a major professional consideration, even by the end of the semester; however, the data did show a consistent and clear pattern of increased critical awareness informing their communication design to be more inclusive. From the same student:

“In the end, it isn’t just about disabilities, it is about everyone’s right to be a part of society and to make their own choices in their lives.” [Source: Reflection 4 in response to Samuels (2013)]

Conclusion

This article addresses the need for more research on pedagogical practices that supplement instrumental considerations of communication design with ethical considerations of social justice. As instructors have expressed difficulty and concern for how to implement such practices in their teaching, we have proposed a strategy: introducing issues of social justice to students by initially pointing their attention to disability and its immediate and more accessible exigency to communication design.

Drawn from our action-research/service-learning project in which such a class was taught, we present three themes from students’ discussion and practice: 1) an expanded notion of what it means to be an effective, credible, and ethical technical communicator; 2) an ability to recognize exclusionary communication design and revise toward inclusivity; and, as they begin to view accessible composing not only as a role of communication designers, but as an ethical commitment to inclusivity, many students 3) articulated a more complex critical awareness of social justice beyond concerns specific to disability.

These themes are not disparate, and their relationships are important. We believe that the earlier themes are a precondition for the later themes. In viewing the distribution of themes in Table 1, we can see that theme C appears more frequently in data types produced toward the end of the semester and that it almost always appears after or alongside the first two themes (A and B). This suggests that inclusive practices facilitated by attention to accessibility can serve as first steps in enacting social justice as a professional habit in the sense of a neo-Aristotelian virtue. Technical communication instructors interested in social justice are struggling to find ways of introducing the topic to students who are accustomed to instrumentalist ways of thinking (Scott 2004). From a student interview:

“Part of the reason we’re taking this [course] is to see the different points of view and to form our own opinions about it. And to a certain extent, we do need that background to see where all these other people are coming from. But, since it’s a course that’s preparing us to go out into the work-field and to be technical writers, I did feel that we need to have most everything in the course to have a practical application.” [Source: Interview]

We believe understanding these connected themes as conditions for one another (not necessarily as a progression, though it might occur in that manner) can help instructors develop pedagogical strategies for implementing social justice concerns. Importantly for reaching instrumentalist students, these strategies are neither didactic nor extraneous to the most important issues in the field.

For students to begin thinking of communication design as an ethical endeavor, one with implications of social justice, they must also see such an ethical stance as relevant to their personal and professional goals. Research shows that students are more motivated to learn if the instructor connects the material to students’ interests and that incorporating goal-directed practices is critical (Ambrose et al. 2010). This is why beginning the conversation with disability is so fruitful. Accessible design feels practical to students, so it is congruent with instrumentalist views of the field. This strategy allows instructors to introduce social justice by building out from a shared foundation.

In what they may expect to be an instrumental course on digital media, students can be unwilling to engage with “uncomfortable” injustices relating to race, sexuality, and other identities. Starting with disability allows students to recognize more easily the existence of privilege and how societal norms serve some populations better than others. This places the students in a better position to talk about what they might consider more uncomfortable facets of privilege (race, gender, class)—facets many of them have been taught to reject outright or view as an agenda in contradiction to their own personal value systems. Disability is not readily associated with any particular political position and thus can enable more digestible consideration of other social justice topics.

Our hope is that this article will provide not only new strategies for those introducing students to the idea that social justice is relevant to communication design but also give encouragement to those instructors who wish to do so but do not know where to begin. As a concluding remark, let us say that by positing disability as insight into social justice pedagogy in communication design, we have no wish to relegate disability as an issue of lesser importance or lesser complexity than other issues (such as race, class, gender, and sexuality). Just because we are advocating disability as a starting point to engage with broader concerns of social justice does not mean that disability in and of itself does not require deep critical engagement. If anything, not enough work has been done on disability in communication design, particularly technical communication, and here we help raise disability as a central concern for all technical communicators, especially those instructors interested in social justice pedagogy.

Acknowledgments

We’d like to thank Jeanie Peck and Alma Burgess at the Center for Persons with Disabilities at Utah State University. Their partnership was key to the service-learning component of the course we discuss in the article. Thank you also to our students, who graciously participated in this research, allowing us to learn alongside them. We would also like to thank special issue editor Andrew Lucchesi for bringing this issue to fruition and to acknowledge Sushil Oswal’s contribution in conceptualizing this special issue.

Bibliography

Agboka, Godwin Y. 2013. “Participatory localization: A Social Justice Approach to Navigating Unenfranchised/disenfranchised Cultural Sites.” Technical Communication Quarterly 22(1): 28–49.

Ambrose, Susan A., Bridges, Michael W., DiPietro, Michele, Lovett, Marsha C., and Marie K. Norman. 2010. How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Aristotle. 2011. Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, trans. Robert C. Bartlett and Susan D. Collins (Chicago: U of Chicago P).

Baynton, Douglas C. 2013. “Disability and the Justification of Inequality in American History.” In The Disability Studies Reader, 4th edition, edited by Lennard J. Davis (New York, NY: Routledge), 17-33.

Blythe, Stuart, Grabill, Jeffrey T. and Kirk Riley. 2008. “Action Research and Wicked Environmental Problems: Exploring Appropriate Roles for Researchers in Professional Communication.” Journal of Business and Technical Communication 22(3): 272-298. .

Bowdon, Melody. 2004. “Technical Communication and the Role of the Public Intellectual: A Community HIV-prevention Case Study.” Technical Communication Quarterly 13(3): 325–340.

Braun, Virginia and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2): 77–101.

Clark, Dave. 2004. “Is Professional Writing Relevant? A Model for Action Research.” Technical Communication Quarterly 13(3): 307-323.

Crabtree, Robbin D. and David Alan Sapp. 2005. “Technical Communication, Participatory Action Research, and Global Civic Engagement: A Teaching, Research, and Social Action Collaboration in Kenya.” REFLECTIONS: A Journal of Rhetoric, Civic Writing and Service Learning, 4(2): 9–33.

Davis, Lennard J., ed., 2013a. The Disability Studies Reader, 4th ed. New York: Routledge.

Davis, Lennard J. 2013b. “Introduction: Disability, Normality, and Power.” In The Disability Studies Reader, 4th ed., edited by Lennard J. Davis (New York: Routledge), 1-16.

Denzin, Norman K. 1978. Sociological Methods. (New York: McGraw-Hill).

Elmore, Kimberly. 2013. “Embracing Interdependence: Technology Developers, Autistic Users, and Technical Communicators.” In Rhetorical Accessability, edited by Lisa K. Meloncon (Amityville, NY: Baywood), 15-38.

Emens, Elizabeth F. 2013. “Disabling Attitudes: U.S. Disability Law and the ADA Amendments Act.” In The Disability Studies Reader, 4th ed., edited by Lennard J. Davis (New York: Routledge), 42-60.

Faber, Brenton D. 2002. Community Action and Organizational Change: Image, Narrative, and Identity. (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois UP).

Garver, Eugene. 2006. Confronting Aristotle’s Ethics: Ancient and Modern Morality. (Chicago: U of Chicago P).

Grabill, Jeffrey T. 2000. “Shaping Local HIV/AIDS Services Policy through Activist Research: The Problem of Client Involvement.” Technical Communication Quarterly 9(1): 29-50.

Gutsell, Margeret and Kathleen Hulgin. 2013. “Supercrips Don’t’ Fly: Technical Communication to Support Ordinary Lives of People With Disabilities.” In Rhetorical Accessability, edited by Lisa K. Meloncon (Amityville, NY: Baywood), 84-94.

Haas, Angela M. 2012. Race, Rhetoric, and Technology: A Case Study of Decolonial Technical Communication Theory, Methodology, and Pedagogy. Journal of Business and Technical Communication 26(3): 277–310.

Herndl, Carl. G., ed., 2004. “Critical Practice in Rhetoric and Professional Communication.” Special issue, Journal of Business and Technical Communication 18(1).

Jarrett, Caroline, Redish, Janice (Ginny), and Kathryn Summers. 2013. “Designing for People Who Do Not Read Easily.” In Rhetorical Accessability, edited by Lisa K. Meloncon (Amityville, NY: Baywood), 39-66.

Jones, Natasha N. and Rebecca Walton. Forthcoming. Using Narratives to Foster Critical Thinking About Diversity and Social Justice, in Integrating Theoretical Frameworks for Teaching Technical Communication, M. Eble and A. Haas (eds.).

Lewthwaite and Swan 2013 “Disability Web Standards, and the Majority World.” In Rhetorical Accessability, edited Lisa K. Meloncon (Amityville, NY: Baywood), 157-174.

Leydens, Jon A. 2012. “What does Professional Communication Research have to do with Social Justice? Intersections and Sources of Resistance.” In Professional Communication Conference (IPCC), 2012 IEEE International 1-13.

Linton, Simi. 1998. Claiming Disability: Knowledge and Identity. New York, NY: NYU Press.

MacIntyre, Alasdair C. 2007. After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory, 3rd ed. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Meloncon, Lisa K., ed. 2013a. Rhetorical Accessability: At the Intersection of Technical Communication and Disability Studies. (Amityville, NY: Baywood).

Meloncon, Lisa K. 2013b. “Toward a Theory of Technological Embodiment.” In Rhetorical Accessability, edited by Lisa K. Meloncon (Amityville, NY: Baywood), 67-82.

Miles, Matthew B., and A.M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA: Sage).

Miller, Carolyn R. 1979. “A Humanistic Rationale for Technical Writing.” College English 40(6): 610–617.

Moeller, Ryan, Walton, Rebecca, and Ryan Price. 2015. “Participant Agency and Mixed Methods: Viewing Divergent Data Through the Lens of Genre Field Analysis.” Present Tense 5(1).

Moore, Kristen. 2013. “Exposing Hidden Relations: Storytelling, Pedagogy, and the Study of Policy.” Journal of Technical Writing and Communication 43(1): 63-78.

Nozick, Robert. 2013. Anarchy, State, Utopia, 2nd ed. (New York: Basic Books).

Oswal, Sushil K., and Beth L. Hewett. 2013. “Accessibility Challenges for Visually Impaired Students and Their Online Instructors.” in Rhetorical Accessability, edited by Lisa K. Meloncon (Amityville, NY: Baywood), 135-156.

Patton, MQ. 1999. “Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis.” HSR: Health Services Research. 34(5) Part II: 1189-1208.

Price, Margaret. 2013. “Defining Mental Disability.” In The Disability Studies Reader, 4th ed., edited by Lennard J. Davis (New York: Routledge), 298-307.

Rawls, John. 1971. A Theory of Justice. (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard UP).

Rude, Carolyn. D. 2009. “Mapping the Research Questions in Technical Communication.” Journal of Business and Technical Communication 23(2): 174–215.

Samuels, Ellen. 2013. “My Body, My Closet: Invisible Disability and the Limits of Coming Out.” In The Disability Studies Reader, 4th ed., edited by Lennard J. Davis (New York: Routledge), 316-332.

Scott, J. Blake. 2004. “Rearticulating Civic Engagement through Cultural Studies and Service-Learning.” Technical Communication Quarterly 13(3): 289-306.

Scott, J. Blake. 2008. “The Practice of Usability: Teaching User Engagement Through Service-Learning.” Technical Communication Quarterly 17(4): 381-412.

Scott, J. Blake, and Bernadette Longo, eds., 2006. “Making the Cultural Turn.” Special issue, Technical Communication Quarterly 15(1): 3-7.

Vallor, Shannon. 2010. “Social Networking Technology and the Virtues.” Ethics and Information Technology 12(2): 157-170.

Walton, Rebecca, and Natasha N. Jones. 2013. “Navigating increasingly cross-cultural, cross-disciplinary, and cross-organizational contexts to support social justice.” Communication Design Quarterly Review 1(4): 31-35.

Walton, Rebecca, Zraly, Maggie, and Jean Pierre Mugengana. 2015. “Values and Validity: Navigating Messiness in a Community-Based Research Project in Rwanda.” Technical Communication Quarterly 24(1): 45–69.

Williams, Robin. 2010. The Non-Designer’s Presentation Book: Principles of Effective Presentation Design. Berkeley, CA: Peachpit Press.

Youngblood, Susan A., and Jo Mackiewicz. 2013. “Lessons in Service Learning: Developing the Service Learning Opportunities in Technical Communication (SLOT-C) Database.” Technical Communication Quarterly 22(3): 260–283.

Zdenek, Sean. 2011. “Which Sounds Are Significant? Towards a Rhetoric of Closed Captioning.” Disability Studies Quarterly 31(3). http://www.dsq-sds.org/article/view/1667/1604

[1] Email correspondence, July 12, 2014.

[2] Like almost all IRB-approved studies, ours allows participants to withdraw at any time—including after grades were submitted—but it was in the period before grade submission that the risk of coercion warranted an intermediary in the withdrawal process.

About the Authors

Jared S. Colton is an assistant professor of technical communication and rhetoric at Utah State University. His research addresses the intersections of rhetorical theory, ethics, and politics within professional and technical communication, whether in pedagogy or sites of social justice. He is particularly interested in how classical and contemporary ethical frameworks inform the production, practice, and critique of collective activism via social and mobile media and accessibility technologies. He has published in Enculturation, Rhetoric Review, and the Journal of College Science Teaching.

Rebecca Walton is an assistant professor of technical communication and rhetoric at Utah State University. She studies the role that communication can play in more equitably distributing power. Her research interests include social justice, human dignity and human rights, and qualitative methods for cross-cultural research. Her work has appeared in Technical Communication Quarterly; Journal of Business and Technical Communication; and Information Technologies and International Development, as well as other journals and edited collections.