“All Corners of the World”: the Possibilities and Challenges of International Electronic Education

Sheila Cavanagh, Emory University

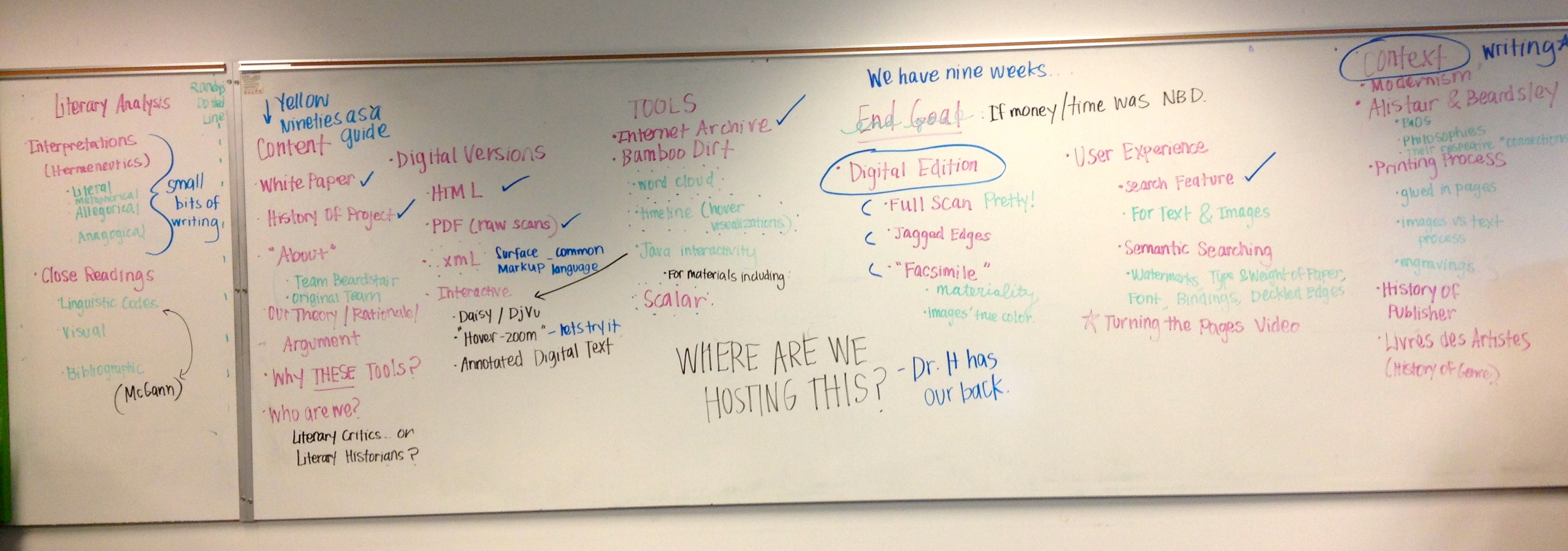

Abstract

The World Shakespeare Project (WSP) uses videoconferencing to link students in the US, UK, India, Morocco, Argentina, Brazil, and North American Tribal Colleges. This essay discusses the practical and theoretical bases of this project, including its background in brain-based learning. The WSP engages students in wide-ranging discussions and performance exercises, facilitating pedagogical communication between a disparate group of international institutions.

The World Shakespeare Project (WSP) uses new media to enable college and university students to interact academically across several continents, including North and South America, Europe, Asia, and North Africa. We also collaborate with incarcerated students studying Shakespeare at Monroe Correctional Facility in Washington State and have begun partnership discussions with universities in Ethiopia. Though an increasing number of online educational models rely on asynchronous communication, the WSP focuses on live interaction whenever possible. Some of the WSP’s partners are located in urban centers, with access to diverse modes of information and communication technology. Others reside in comparatively isolated rural regions, with limited technological facilities. Nevertheless, as much as possible, the WSP promotes “real time” academic and cultural conversation between disparate groups of students who are studying Shakespeare.

This essay details some of the pedagogical, philosophical, and technological facets that simultaneously invigorate and challenge this project. Since the beginning, the WSP has benefitted greatly from the kind of collaborative engagement that undergirds so many electronic academic projects. At the start, the WSP included co-instructors who inhabited different continents: Sheila T. Cavanagh (author of this piece), Professor of English at Emory University in Atlanta, had just been named Emory College Distinguished Teaching Professor. Kevin Quarmby, a long-time professional actor in the United Kingdom, had recently completed his PhD and was teaching for a variety of academic programs in London.[1] Cavanagh had taught a “Shakespeare in Performance” course for many years and the pair determined that introducing an actor turned scholar into the academic mix might prove valuable. At the outset, neither participant had any real idea of what would happen and how students would receive it. Needless to say, however, this initial foray became a resounding success. After a few months of linking classes between London and Atlanta, Cavanagh (with support from the Halle Center for Global Learning) called an international meeting of expert faculty and educational technologists and began exploring the promises and pitfalls of global education through videoconferencing. Soon afterwards, the World Shakespeare Project was born. Within a couple of years, the WSP had expanded its partnerships across many continents, time zones, and cultural differences, creating vibrant exchanges between students, faculty, and technologists in widely disparate settings.

The WSP uses videoconferencing, iPads, iPhones, Blackboard, email and other electronic resources to redesign traditional classroom encounters. In some sessions, participants from multiple venues participate in what we term “on yer feet” performance modules designed to recreate the rehearsal process followed by actors at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre or Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in London. Other times, students in places such as Atlanta and Casablanca join email or videoconference conversations that range from textual analysis to cultural exchange and discussions about educational, historical and familial differences related to Shakespearean drama. This essay uses the WSP to illustrate the kinds of educational opportunities and questions that modern technology can facilitate. While these benefits are not exclusive to Shakespeare, his drama appears to offer unusual ways to engage people from multiple cultures, something that London’s 2012 Globe to Globe Festival illustrated magnificently when 37 Shakespeare plays were presented in 37 different languages. Shakespeare’s recurring presence in theatres and classrooms around the world makes it particularly valuable for cross-cultural conversations and collaborations, although the techniques we employ are designed to be transferable across disciplines. Shakespeare may not achieve universality, but the canon still provides access to an international academic conversation that many, including the College Board’s Lawrence Gladieux (1999), worry could be undercut by expanding technology use. As he suggests, “the virtual campus may widen opportunities for some, but not generally for those at the low end of the economic scale. [. . .] The Internet has great power and potential for good, which we must harness to the cause of educational opportunity. We must not let information technology become a new engine of global inequality” (3). Noted educational theorist Philip Altbach (2007) raises similar concerns, remarking, “Contemporary inequalities may in fact be intensified by globalization” (2).

If employed judiciously, however, electronic communication creates portals for international and other cross-institutional interactions that were previously unimaginable. As the WSP has grown, it established partnerships with a range of distinctive institutions. The exchanges are vibrant and valuable for those involved. Often, however, these collaborations do not fit the profile regularly invoked at Emory when academic linkages are discussed. WSP partnerships frequently do not involve “peer institutions”; they do not necessarily formalize ties with the kinds of prestigious colleges and universities Emory typically races to embrace. Instead, the specific WSP collaborations emphasized today bring together Emory students—enrolled at an American private university that prides itself on its US News & World Report “top 20” ranking—with students who are commonly the first members of their families to participate in tertiary education. Some of the non-Emory students come from families completely lacking in formal education. Distinctive from most Emory undergraduates, these WSP collaborators often come from homes and communities where educational opportunities have been extremely limited, where English is rarely or never spoken, and/or where role models for economic, professional, and academic success remain hard to find. Rather than seeking personal advancement by attending a wealthy, well-established private university, many of these students study, for example, in tribal colleges, institutions that were created specifically to bring higher education to what is often, though controversially, called “indigenous” populations. As Ladislaus Semali and Joe Kincheloe (1999) suggest, “indigenous knowledge is an ambiguous topic that immediately places analysts on a dangerous terrain. [. . .] Nevertheless, we perceive the benefits of the study of indigenous knowledge sufficiently powerful to merit the risk” (3). They further encourage goals closely resembling those of the WSP, namely, “enhancing the internationalization of the curriculum of academic institutions by giving faculty and students ready access to a global network of indigenous knowledge resource centers” (Semali and Kincheloe 1999, 5). This essay emphasizes the value of including eclectic international, indigenous, and incarcerated students with more mainstream partners and teaching materials. The WSP promotes these kinds of “asymmetrical” academic collaborations. In a 1947 UNESCO symposium on “The Universal Right to Education,” I. L. Kandel notes that “even when equality of educational opportunity is provided, certain social and economic classes feel that the opportunities are not intended for them” (quoted in Spring 2000, 16-17). While this situation arguably continues today, the WSP operates from an assumption that opposes such educational divides. As Michael Peters (2006) argues, “The economics of knowledge and information is not one of scarcity [. . .] but rather one of abundance, for, unlike most resources that are depleted when used, information and knowledge can be shared and can actually grow through application” (96). If this is the case, the Shakespeare world and the broader educational community has much to gain by sharing information and concerns with faculty and students who were essentially impossible to reach prior to the availability of modern technologies such as videoconferencing.

Typically, WSP interactions by email or videoconferencing focus predominantly on Shakespeare, but they also allow participants the opportunity to converse on other topics. Emory undergraduates, for example, tend to know little or nothing about African literature. In the midst of discussions about Shakespeare’s prominent place in British drama, therefore, Moroccan students frequently urge the Americans to read significant global authors such as Tahar Ben Jelloun and Driss Chraïbi. Other international classes have provided similarly unforeseen but fruitful interventions. During a session linking Emory with undergraduates in Argentina and director Tom Magill in Northern Ireland (director of Mickey B, a film version of Macbeth acted by prisoners in Belfast), for instance, the conversation took an unexpected detour after a chance comment about frequent journalistic comparisons between Lady Macbeth and diverse contemporary and historic female political figures. At the mention of then recently deceased Margaret Thatcher in this context, everyone in Argentina and Belfast cringed, while Emory students looked on without comprehension. The ensuing discussion circled back to Macbeth, but also included illuminating accounts of British actions in the Maldives/Falkland Islands and their treatment of political prisoners during the Irish “troubles.” Such unanticipated, fruitful results from our encounters with far-flung partner colleges are common. In the middle of a segment devoted to passages from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, for example, one student’s face appeared transformed as realization dawned. For this young mother, a full time student at Saginaw Chippewa Tribal College in Michigan (www.sagchip.edu) and a leader in her tribe, a section of Shakespeare’s text suddenly hit home, as documentary maker Steve Rowland’s film of the class indicates:

[youtube width=”700″ height=”394″]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YJl6ELWUBLM[/youtube]

Shakespeare describes Prospero, the exiled Milanese Duke in The Tempest, arriving by ship at a remote island. In the years that followed, Prospero claims sovereignty over the land and its inhabitants, namely, a magical being called “Ariel” and the locally-born “monster” Caliban. Numerous Shakespeareans in recent years have written about postcolonial interpretations of this play (Thomas Cartelli, for instance), but this nontraditional Chippewa student needed no post-colonial insights to grasp familiar implications from the text. As soon as the words were spoken aloud, she exclaimed about the parallels between the history of American tribal populations and what had happened to the natives of Shakespeare’s unnamed island. Shakespeare was clearly telling the story of her people despite the centuries separating his writings from contemporary society.

[youtube width=”700″ height=”394″]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zoe23j8zFio[/youtube]

As often happens, Shakespeare’s narratives found immediate resonance with a temporally and geographically distanced audience. As this American Indian student explained, the challenges associated with Shakespeare’s language did not overpower the cultural connections his drama forged with the students at this Midwestern Tribal College, one of the thirty-seven colleges forming AIHEC or the American Indian Higher Education Consortium.

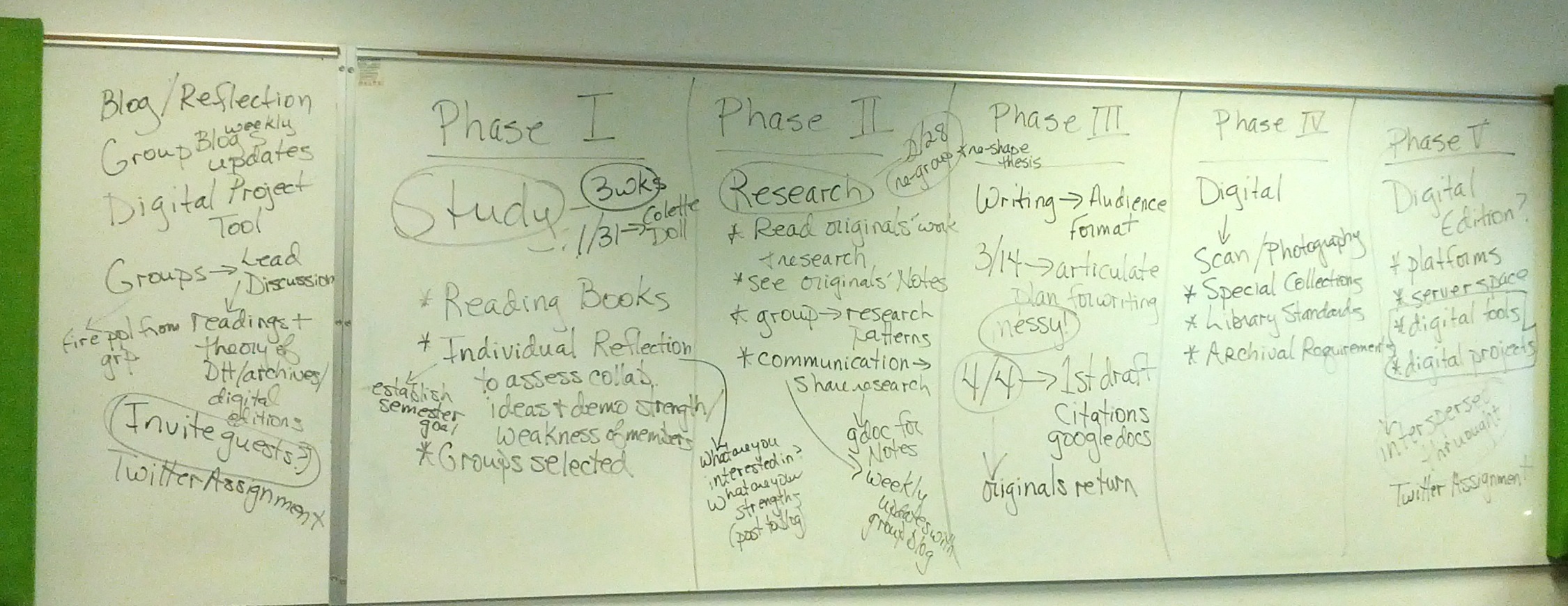

A few months earlier, students at Sido Kanhu Murmu University, an institution established for the local tribal population in Dumka, Jharkhand, India, experienced a similarly striking Shakespearean moment. Performing the trial scene from The Merchant of Venice in their native Santali dialect, these first-generation learners then shared childhood stories of watching their parents being beaten by local moneylenders and discussed how these memories helped shape their representation of the moneylender Shylock in Shakespeare’s play.

Figure 1. Students at Sido Kanhu Murmu University

The power of these students’ stories and the resonance between their life histories and the details of Shakespeare’s texts was palpable for all who witnessed it in person or through viewing the flawed electronic record. Dumka, a recipient of financial support from India’s “Backwards Regions Grant Fund,” has not typically been involved in international educational dialogues. Until the advent of widespread modern technology, they had no opportunity to discuss intersections between their lives and these plays with anyone outside their local environments.

The tribal colleges and universities the WSP works with in India are located in comparatively remote regions that suffer from poverty and geographical isolation compounded by the significant presence of armed Maoist rebels. Those conditions often make travel dangerous and occasionally interfere with the possibility of electronic communication. In March, 2014, for example, 15 policemen were ambushed and killed by Maoist insurgents in the state of Chhattisgarh, a region adjacent to WSP partner communities. The students who attend these tribal colleges typically reside in homes with only basic amenities or they stay in local hostels. Faculty often provide supplementary meals as well as education for their undergraduates. During site visits to homes of several WSP educational partners in Purulia, West Bengal and Dumka, Jharkhand, students regularly comment that they have never met a “foreigner” before. The students majoring in English literature typically plan to teach English in elementary or secondary school, although occasionally, the WSP encounters students with aspirations for advanced degrees. One student in Dumka, for example, who performed Shakespearean scenes during site visits in 2012 and 2013, plans to translate all of the Merchant of Venice into Santali as part of the doctoral study he hopes to undertake after he completes the M.A. he is currently pursuing. In this same environment, however, where doctoral education can now be imagined, several local women are killed every month after accusations of witchcraft, an occurrence documented in the international press as well as in student and faculty narratives. In studying plays such as Macbeth, the combination of such contradictory perspectives within the same villages opens up remarkable possibilities for discussion and research. Students’ own experiences enable them to respond to many facets of the drama, such as Shakespeare’s integration into his plays of folk beliefs, intellectual conceptualizations, and common human emotional experiences.

The dynamic pedagogical snapshots described above occurred during site visits undertaken by the WSP in preparation for its subsequent live videoconferencing sessions. Created with seed grant funding in 2011 from Emory’s Halle Institute for Global Learning (halleinstitute.emory.edu) and Emory’s Center for Interactive Teaching, in 2012 the WSP became the sole recipient of Emory’s “High Risk/High Potential Initiative” grant (Guo 2012). Throughout its development, the WSP has collaborated with a team of talented educational technologists in order to create a template for synchronous global educational exchange that can facilitate a similar linking of international institutions seeking a range of pedagogical and disciplinary goals. Collaborators are chosen both through strategic planning and through less structured means. As noted above, collaborators encompass students and institutions from a broad spectrum of religious, national, linguistic, and socioeconomic backgrounds. While the partnerships involved vary considerably, the WSP always seeks to align with the tenets Renate Nummela Caine and Geoffrey Caine (1994) associate with “brain-based learning” which, in their terms,

involves the entire learner in a challenging learning process that simultaneously engages the intellect, creativity, emotions, and physiology. It allows for the unique abilities and contributions from the learner in the teaching-learning environment. It acknowledges that learning takes place within a multiplicity of contexts—classroom, school, community, country and planet. It appreciates the interpenetration of parts and wholes by connecting what is learned to the greater picture and allowing learners to investigate the parts within the whole. (9)

As much as possible, the WSP employs these and other concepts of brain-based learning.[2] As we expand our scope, we hope to create additional ways that cooperative international education can draw from key pedagogical and technological advances in order to enhance the educational experience for all concerned. Since an expansion in contemporary research focused on cognition and learning has paralleled the growth in educational technology, the WSP actively draws from experts in both areas as it develops its curriculum.[3]

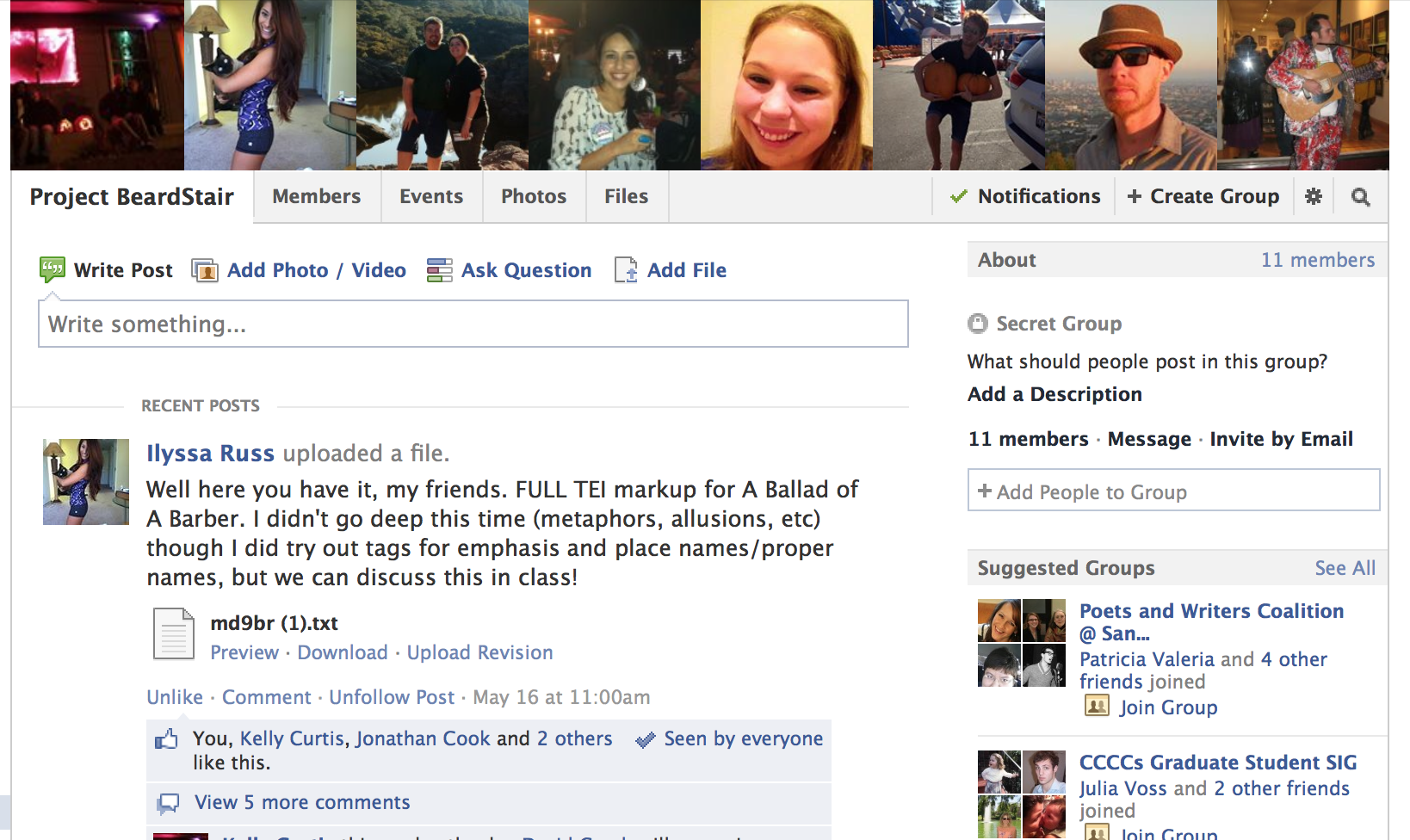

The performance exercises that remain central to WSP classes were initially transmitted through Skype, more through default than design. The instructors already communicated regularly through Skype and the platform was relatively available and reliable. While the WSP’s reliance on fairly basic technology originated without conscious deliberation, however, it has now become an important philosophical tenet of the project, employed whenever possible. Although the WSP regularly tests more sophisticated videoconferencing platforms, such as Vidyo, the Blue Jeans Network, and others, we insist upon widespread availability. Sometimes our partners can take advantage of Emory’s site licenses to gain access to advanced technologies; nevertheless, we remain committed to using the most affordable avenues possible for interactivity. While Emory’s educational technologists are thrilled, therefore, when we partner with an institution that boasts cutting edge equipment or expertise, we resist limiting our interactions to colleges or universities with robust electronic infrastructures. To do so would undermine our primary goal of bringing together widely diverse academic populations. Comparative affluence is not a barrier to participation in the WSP’s educational endeavors, but it is not a demand either. Some of our most memorable exchanges—such as our initial communication with Nistarini Women’s College in Purulia, West Bengal—have relied solely upon an instructor’s laptop, iPad, or iPhone.

Figure 2. Nistarini Women’s College, Purulia, West Bengal

Figure 3. The Macbeths in Purulia, West Bengal, India

Keeping technological requirements as minimal as possible facilitates access with a broad range of institutions and populations. While we still need to confront practical issues, such as time zone differences and varying curricula and exam schedules, therefore, we embrace the joys and frustrations accompanying widely available videoconferencing platforms, such as Skype and FaceTime.

Collaborating with the WSP often leads, however, to expanded technological resources at our partnering institutions, as our affiliation with Université Hassan II Ben M’sik in Casablanca, Morocco demonstrates. In this instance, the WSP traveled to Morocco in late February, 2012, in order to assess local interest in the project. Since we were working predominantly with Hindu communities in India at this time, it seemed appropriate to explore collaborative possibilities with an Islamic institution. At Hassan II, we encountered an enthusiastic group of students, who relished the opportunity to perform scenes from Shakespeare, even though this drama is not currently a regular part of their curriculum. They also eagerly participated in classroom discussions with students in Atlanta, where both groups confessed ignorance about each other’s cultural and educational circumstances. While the Moroccan technological infrastructure was limited, electronic challenges were offset by the collective energy contributed by actively engaged students on both sides of the Atlantic. These international dialogues also reflected what Jay Caulfield (2011) identifies as the power of learning that integrates a “blended classroom” with “online and experiential activities”:

A learner constructs knowledge primarily through dialogue. It is a process whereby the learner internalizes what is being learned by finding a personal application for the new concepts while determining the worthiness of those concepts. (21)

Technology did not enable a “perfect” dialogue, but it did offer students the opportunity to put this Shakespearean study into a context that made sense to them.

In addition, the technological landscape at Hassan II soon changed. Traveling back to Morocco in order to facilitate class meetings during Emory’s inaugural intensive, three-week “Maymester” term, the WSP encountered a completely different technological landscape. Inspired by classroom links with Emory, Université Hassan II had generated sufficient governmental support to institute immediate and extensive upgrades to their facilities. In contrast to the outdated computer used during connections in early March, the May class sessions enjoyed state-of-the-art equipment housed in newly renovated classrooms. As this clip indicates, the local technological support team enthusiastically welcomed these changes, which opened up a host of new electronic possibilities for their campus. As remarkable as this transformation at Hassan II was, the WSP finds that this kind of renewed investment in technology often accompanies institutional involvement in our cross-cultural educational partnerships.

[youtube width=”700″ height=”394″]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZvFgaM1eoCk[/youtube]

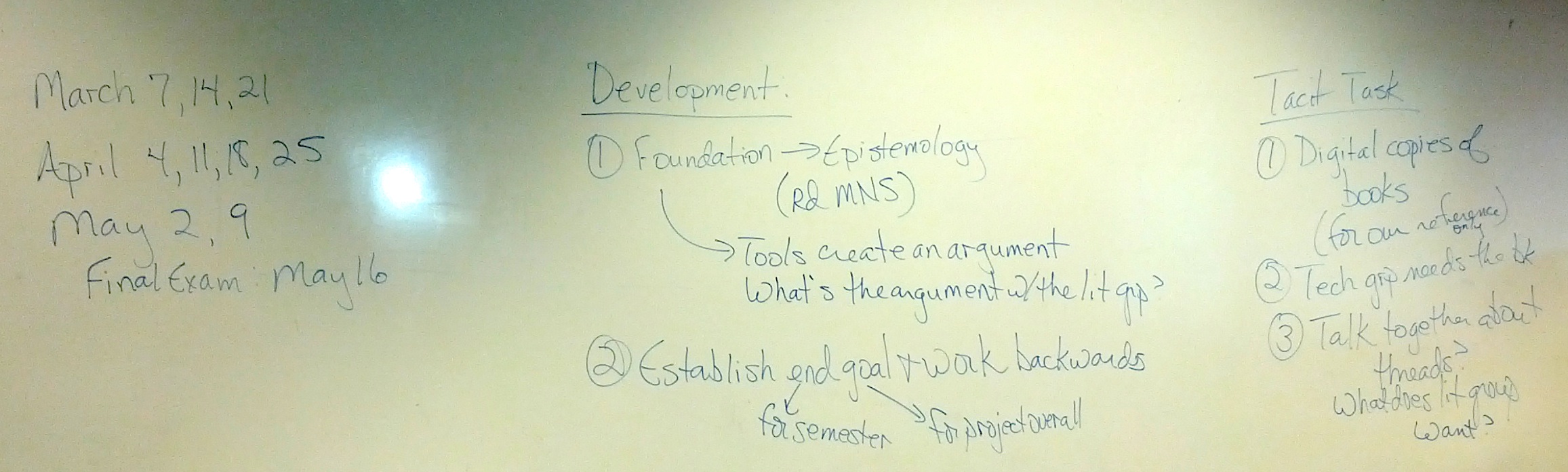

The technological advances enjoyed in Casablanca and elsewhere resulted from the enthusiasm generated when WSP participants recognize the exciting possibilities of such connections, even though most WSP interactions take place only for a few short sessions. For several semesters, however, the WSP experimented with lengthier virtual classroom collaborations. In August, 2012, Quarmby began a tenure-track appointment as an assistant professor of English at Oxford College of Emory University. Oxford College is situated on the site of Emory’s original founding in 1836, about thirty-eight miles from the main campus in Atlanta. Serving first- and second-year students only, Oxford College enrolls about 900 students who move to the Atlanta campus to complete their degrees. For three terms after Quarmby relocated from London, UK to Oxford, Georgia, the WSP offered a “Shakespeare in Text and Performance” class simultaneously to students on both campuses. Using a Cisco High-Definition Videoconferencing system, the students were seated in semi-circles in their respective classrooms, forming a virtual Shakespearean “O” (Henry V, Chorus, prologue 13) to provide space for discussion and performance. Screensharing facilitated joint presentations between students in the two locations, while technical crews supported our regular, extended sessions.

For this shared class, we wanted to eschew premiere technology in order to replicate the experience and resources of our non-Emory partners. Unfortunately, technical issues proliferated, threatening to undermine student patience with the vagaries of electronic communication. As a result, we decided to use the sophisticated room system available to us, while concentrating on how best to integrate students from different locations into a unified classroom experience. Concurrently, we enlisted the expertise of Emory’s Educational Analyst Leah Chuchran, who works on developing appropriate assessment tools to monitor student satisfaction and their dismay with this unconventional configuration. Our periodic adjustments in technological practices and philosophies indicate some of the complicated issues emerging during these electronic pedagogical interactions. We still employ many common videoconferencing tools, but remain open to change, as needed. At the moment, WSP connections with domestic and international partners generally occur in distinct modules. Sometimes these sessions include interactions with multiple sites simultaneously, but they are limited to a few days in duration. These structured parameters provide opportunities for students to engage directly with each other during class and afterwards, but they reduce the scope for the frustration that can develop with longer collaborative units. In our experience, the challenge of keeping a three- or four-site connection live and stable for a few classes does not unduly distract students. When the regular Oxford College / Emory College shared meetings began, however, it quickly became clear that students were not prepared for regular electronic disruptions. Typically, students accommodated the occasional audio or visual glitches with apparent good humor; but more frequent or extended interruptions were not patiently tolerated. While the novelty of videoconferencing has not yet worn off completely, it is no longer sufficiently exotic to override student demands for consistently high-quality exchange when they are communicating with a fairly comparable population. Students typically remain relatively sanguine about electronic mishaps when they are linking up with their peers in culturally distinctive locations, but appear to expect a more seamless connection with those close to home. It seems as though distances that cannot be easily traversed without technology generate more patience than the forty miles separating the two Emory classrooms, particularly since those Georgia conversations include students from reasonably similar backgrounds.

As suggested above, the WSP includes a number of separate, but interrelated elements, including site visits, videoconferencing, visiting fellows, and shared guest speakers. Occasionally, students are even able to meet in person, as when two Emory students served as WSP interns for the 2012 International Theatre Festival hosted by our partner university in Casablanca (www.fituc.ma). Typically, classes share common features, whether the sessions bring together students from abroad, from American Tribal Colleges, or from the relative proximity of urban or rural Georgia. During sessions with performance exercises, for instance, we solicit a “casting director” from each location, who assigns dramatic roles to students on a campus other than their own. This maneuver offers students a way to participate even if they prefer not to recite aloud. At the same time, it gives everyone a chance to interact and makes the casting process less predictable than it might be if students were choosing from a group they are familiar with. A casting director from Morocco, for example, will not know which American students tend to shy away from discussion and which grab the spotlight whenever possible. In comparatively small gatherings, such as those incorporating Emory College, Oxford College, and Saginaw Chippewa Tribal College, it also allows students to build on their growing knowledge of each other.[4] After a few classes, students can refer to one another by name, rather than identifying each other predominantly by gender and clothing. Such shifts both mark and deepen the level of community feeling that the program strives for. Even before such enriched communication becomes possible, however, students exchange significant information about themselves and their cultural backgrounds that provide insights into their lives and environments, while simultaneously illuminating Shakespeare’s texts. An early class session between Atlanta and Casablanca, for example, focused on A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Students in Morocco, who initially were unnecessarily concerned about their level of fluency in English, were emboldened by realizing that Shakespearean vocabulary is difficult even for native speakers of the language. Watching American students struggle with deciphering the surprisingly unfamiliar word “auditor,” for example (Act 1, scene 1), reduced the Casablancan undergraduates’ hesitancy about admitting that there were words in the text they did not know. Soon, a shared willingness to experiment with the unknown brought the students together in a mutual endeavor.

These performance modules invite students to present sight-readings of a given text, an exercise that invariably produces verbal stumbling. After an initial presentation of the lines, the instructors and students start to unravel the chosen passage before the students are invited to offer it again, with their newly found knowledge and insight informing subsequent readings. As Colin Beard and John P. Wilson (2006) note, dramatic exercises such as these can prompt both strategic and fortuitous educational results: “The concept of planned and unplanned learning can be further explored in dramaturgy, which recognizes that learning design and learning outcomes can be both anticipated and unanticipated” (112).

In WSP classes, these modified rehearsal techniques not only increase student comfort with the text, thereby supporting formal curricular goals, but they also open up space for significant unscripted cultural exchanges. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, for instance, many of the central characters are fairies. In discussions between the two countries, students are asked to recount their personal knowledge or experience with fairies. Typically, American students offer lighthearted accounts of these creatures. Happily ignoring the darker side of famous “Western” fairies such as Tinkerbell, Emory undergraduates describe fairies as being playful and effervescent. For American students, fairies spark happy childhood memories. In Morocco, however, fairies evoke malevolence and danger. Students there tell stories of modern day security guards abandoning their posts when fairies were reported in the vicinity. For these undergraduates, fairies connote danger. Some of the Moroccan students we’ve encountered express belief in fairies, while others deem them fantastical, but everyone we have spoken to in Morocco categorizes fairies as evil. Shakespeare’s fairies incorporate both playful and malicious tendencies (Act 2, scene 1). Puck, for example, contains a vicious streak that American students generally overlook until this aspect of the character is specifically highlighted, while Moroccan undergraduates often miss the benign traits associated with the Fairy Queen Titania’s followers. Having peers introduce these topics gives them added resonance, however, that cannot be matched by an instructor’s intervention into discussion. After sharing their cultural preconceptions of this otherworldly set of characters, both groups of students recognize complications in the text that were previously hidden.

Figure 4. Université Hassan II Ben-M’sik, Casablanca, Morocco

In addition to incorporating concepts supporting current theories of cognition and learning, the WSP exemplifies what is popularly, though often confusingly, known as “hybrid” or “blended” learning, a model that combines face-to-face interactions with electronic classroom involvement (Caulfield 2011), via such tools as videoconferencing and email. This type of pedagogy offers students ways to partner with each other and with visitors before, after, or instead of, meeting personally. This particular aspect of hybrid learning is something the WSP frequently explores. As noted, this project has received considerable moral and financial support from Emory University, which has wholeheartedly embraced the goals of the project. As part of this close collaboration with the broader university, the WSP has been able to invite a series of significant visitors to its live and virtual class meetings in order to determine how such hybrid interactions might work in different settings. We were honored the past two years, for example, to welcome University Distinguished Professor Sir Salman Rushdie to participate in sessions about Shakespearean drama and for an evening of “on yer feet” scenes where he undertook the role of Iago from Othello, playing opposite a student’s Roderigo.

In addition to performing, Rushdie was able to introduce the unique perspective of one acclaimed writer discussing another. While involving internationally renowned writers in videoconferencing sessions is unusual, the WSP incorporates theatrical and technological professionals in the physical and virtual classrooms as often as possible in order to deepen the impact of each interaction both within and beyond Emory’s physical boundaries. We regularly include international actors and directors in our sessions with overseas and American Indian partners and invite a number of Shakespeare in Prison practitioners, such as Curt Tofteland (Shakespeare Behind Bars) and Tom Magill (Mickey B) to join our classes.

This pedagogical examination of the technology supporting the curriculum is most pronounced in the WSP “Maymester” course offering “International Shakespeare in a New Media World,” which balances a pedagogical focus equally among the “international,” the “Shakespeare,” and the “new media” elements of the course (Jacobs 2012).

[youtube width=”700″ height=”394″]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F-xmBXmbwMI[/youtube]

The “new media” aspect of the syllabus includes readings, guest speakers, and assignments designed to encourage student engagement with both theoretical and practical aspects of electronic communication. During these discussions, introducing the trajectory leading from 19th century international telegraphy to Skype often transforms students’ understanding of how information is communicated and the similar ways that disparate technologies can foster international dialogue. Students typically have never given much sustained thought to the role of technology in their undergraduate educations. In this course, however, they are asked to deepen their familiarity with a diverse range of current and historical technologies and to give thoughtful consideration to philosophical and ethical issues that arise when these media are implemented. They are concurrently required to make individual connections with international students and others that enrich their Shakespeare work as they grapple with intersections between the drama and their cultural differences. With rare exceptions, these transnational conversations involve ICT (information communication technology), whether the students communicate through phone, email, or videoconferencing. The course also includes discussions and writing assignments exploring the ways that both media and internationalization transform Shakespearean drama.

The final student project assignment guides participants in drawing together these varied course components. Students are asked to use “new” media to create an internationalized Shakespearean product in conjunction with a standard academic essay whereby they present and analyze the electronic, international, and Shakespearean material that led to their creation. Some students fashion electronic books, score operatic compositions, or make movies. Others find innovative ways to bridge cultural and academic divides through multiple media. In one instance, a Mexican and a Korean student joined forces in order to make a complex image merging Macbeth with an Aztec calendar. They then decided to emulate Shepard Fairey by posting copies of their art at different points in Atlanta, using Emory as the epicenter of a four-quadrant grid. Once the posters were hung, they waited for people to view the art, then interviewed passersby about their reactions to the drawing. Finally, in addition to writing the assigned analytical essay, they filmed and edited a documentary video that recounted their process and included segments of their interviews, including a conversation about Macbeth with a local self-described witch.

Figure 5. Aztec Calendar Macbeth

Given that the entire semester lasted only three weeks (with intensive daily meetings), the students’ projects and the analysis they offered were remarkable. By the end of the short term, Emory students in this course had spoken with people in Africa, Asia, Europe, South America, and the Middle East, while engaging in serious consideration about the ways that Shakespeare, the world, and new modes of electronic communication intersect. As the image below suggests, such international interactions consistently generated enthusiastic responses. These students from Universidad del Salvador in Buenos Aires, Argentina, joined the WSP in live sessions in 2013, then performed and discussed Shakespeare for the next two years via videoconferencing with Emory students. Students in each location requested email addresses so that they could continue their conversations privately.

Figure 6. Universidad Del Salvador, Buenos Aires, Argentina

The WSP remains an evolving entity, but the significant progress made since its relatively recent inception suggests that this approach to cooperative, international electronic education holds great promise. Now that many WSP links are well established, we look forward to expanding the number of partners we can effectively communicate with simultaneously and to increasing the ways that students from the diverse participating institutions can work collaboratively. We recently submitted a grant proposal, for instance, to develop partnerships with universities in Ethiopia. We know, of course, that any shifts in or additions to our collaborations or our techniques will introduce new issues that will need to be addressed. Our commitment to international technological and pedagogical cooperation creates both opportunities and pitfalls. The modern electronic technology journey continues to provide a host of challenges and possibilities that the WSP hopes to confront productively. As Shakespeare might have said, the course of true learning never did run smooth, but the opportunities for global educational exchange continue to stimulate pedagogical advancements. The intersection of Shakespeare and videoconferencing portends a dynamic pedagogical future.

Bibliography

Altbach, Philip G. 2007. “Globalization and Forces for Change in Higher Education.” International Higher Education. The Boston College Center for International Education. Number 50. OCLC 62585048. http://www.bc.edu/content/dam/files/research_sites/cihe/pdf/IHEpdfs/ihe50.pdf

Beard, Colin and John P. Wilson 2006. Experiential Learning. London: Kogan Page. OCLC 71145611.

Caine, Renate Nummela and Geoffrey Caine. 1994. Making Connections: Teaching and the Human Brain. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley. OCLC 30475673.

Cartelli, Thomas. 1987. “Prospero in Africa: The Tempest as Colonialist Text and Pretext.” In Shakespeare Reproduced: The Text in History and Ideology, edited by Jean E. Howard and Marion F. O’Connor. New York: Methuen. 99-115. OCLC 15790380.

Caulfield, Jay. 2011. How to Design and Teach a Hybrid Course. Sterling, VA: Stylus. OCLC 750943378.

Emorysummerprograms. 2012. “International Shakespeare in a New Media World.” Sheila T. Cavanagh and Kevin Quarmby. Maymester, Emory University. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PDhqA73ISpg.

Gladieux, Lawrence E. 1999. “Global Online Learning: Hope or Hype.” International Higher Education: The Boston College Center for International Higher Education. Number 18. OCLC 62585048. http://www.bc.edu/content/dam/files/research_sites/cihe/pdf/IHEpdfs/ihe18.pdf.

Guo, Ling. 2012. “Research Funds Available for Faculty Research in All Disciplines.” Emory Report. May 30. http://news.emory.edu/stories/2012/05/er_university_research_committee_funding/campus.html

Halle Institute. 2012. “World Shakespeare Project.” http://halleinstitute.emory.edu/research/world_shakespeare_project/.

Jacobs, Hal. 2012. “Skyping Shakespeare.” Emory Quadrangle. Accessed 25 September, 2014. http://www.college.emory.edu/home/news/quadrangle/2012fall/pages12_15.html.

Peters, Michael A. with Tina Besley. 2006. Building Knowledge Cultures: Education and Development in the Age of Knowledge Capitalism (Critical Education Policy and Politics). New York: Rowman and Littlefield. OCLC 62322201.

Semali, Ladislaus and Joe L. Kincheloe, eds. 1999. What is Indigenous Knowledge? Voices from the Academy. New York: Falmer Press. OCLC 52467562.

Shakespeare, William. 1986. The Oxford Shakespeare: The Complete Works. Edited by Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor. Oxford, U.K.: Clarendon Press. OCLC 15548918.

Spring, Joel H. 2000. The Universal Right to Education: Justification, Definition, and Guidelines. Mahwah, N.J.: Laurence Erlbaum Associates. OCLC 45732162.

Wikipedia Contributors. 2014. “Shepard Fairey.” In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 24 September, 20:09 UTC. Accessed 25 September. http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Shepard_Fairey&oldid=626939361.

World Shakespeare Project. Directed by Sheila T. Cavanagh. www.worldshakespeareproject.org.

[1] Quarmby is no longer participating in the WSP, but we appreciate his involvement in the early development of this project. We also thank all the educational technologists at Emory who support the WSP, including Jason Brewer, Brenda Rockswold, Barbara Brandt, Wayne Morse, Jr., Stewart Varner, and numerous others. Emory’s ongoing commitment to this project is gratefully acknowledged.

[2] Long after I received my PhD, Emory provided support for me to complete a Master’s Degree focused on cognition and learning through the University of New Hampshire’s Center for Teaching Excellence. I wish to acknowledge both Emory and UNH with gratitude.

[3] In an effort to support future innovation, all theses sessions are recorded. The students sign consent waivers, so that a pedagogical archive can be fashioned while simultaneously serving immediate teaching goals.

[4] Classes in India and Morocco tend to include dozens of students. Class sizes in Argentina vary considerably between institutions: some class sessions include a handful of Argentinean students; others fill an auditorium. At the two Emory campuses, the WSP Shakespeare courses are limited to 20 students per site. The drama class linking Saginaw Chippewa Tribal College with the WSP was a new course, specifically established in order to facilitate this partnership, with only a handful of students enrolled. Our Tribal College collaborators, Cankdeska Cikana Tribal College in North Dakota (http://www.littlehoop.edu) and Saginaw Chippewa Tribal College in Michigan, have total student populations that comprise no more than 200 students. Currently, we are working with Scott Jackson of Shakespeare Notre Dame in order to further our Tribal College initiative, which is being supported by the Royal Society of the Arts (http://www.blog.rsa-us.org/2013/05/the-world-shakespeare-project-received-challenge-grant/).

About the Author

Dr. Sheila T. Cavanagh, founding director of the World Shakespeare Project (www.worldshakespeareproject.org), is Professor of English and Distinguished Teaching Scholar at Emory. She also held the Masse-Martin/NEH Distinguished Teaching Professorship. Author of Wanton Eyes and Chaste Desires: Female Sexuality in the Faerie Queene and Cherished Torment: the Emotional Geography of Lady Mary Wroth’s Urania, she has also published widely in the fields of pedagogy and of Renaissance literature. She is also active in the electronic realm, having directed the Emory Women Writers Resource Project (womenwriters.library.emory.edu) since 1994 and serving for many years as editor of the online Spenser Review.