Nancy Ross, Dixie State University

Abstract

In this article, the author draws on her experience teaching an undergraduate art history course using student-built interactive data visualizations to explore the social relationships of 20th century women artists. This approach increased student engagement despite the conservative environment of Dixie State University. Students learned to critique secondary sources, used digital tools to find results, and engaged in transformative learning advocated by critical pedagogy (Freire et al. 2000). This evidence supports the argument that digital tools and methods should be used not only in advanced scholarly research, but in undergraduate classrooms as well.

Art history, in my opinion, is a surprisingly traditional field. Art history textbooks are full of Western European men who were deified by later Western European men employing some variant of the Great Man theory (Carlyle 1888, 2). Today, many art historians employ contemporary methodologies that move art history away from its past, but some art historians still teach the gender biases of the past.

The discipline of art history has a lot to gain from employing digital methods, but has not yet reached a level of digital sophistication. In his blog post on the future of digital art history, Bob Duggan (2013) asks, “Can the study of art history stop looking like ancient history itself?” Murtha Baca and Anne Helmreich (2013) believe that it can and outline five phases of development in digital humanties, which they offer as inspiration for digital art history. Phase one began with digitizing works of art and texts related to art. Phase two involved building new tools like Zotero and Omeka. The third phase focused on using new technology to create visualizations and recreations and the fourth phase implemented open peer review. In the fifth phase, scholars have engaged in research enabled by “computational analytics.”

Many institutions are diligently working on the first phase. A good example of this is The Getty, which recently released a number of high-resolution images of works of art in its collections to the public domain (Cuno 2013). There are some second phase tools available, such as ARTstor and the Google Art Project, but digital art history has stalled in the third phase.

Perhaps the fastest way to change the discipline of art history is to teach the change you want to see, to rephrase Gandhi. Art historians need to embrace digital tools, but they also have other challenges, such as addressing long-held gender biases. Critical pedagogy in a university setting addresses the question, “How can university teachers practice pedagogy which is attentive to how their students might as citizens of the future influence politics, culture and society in the direction of justice and reason?” (McLean 2006, 1). In approaching the teaching of Twentieth Century Art at Dixie State, a conservative university in southern Utah, this question was foremost in my mind. I knew most of my students before the semester started, having had them in previous classes. These students openly and privately expressed concerns over issues of gender and sexuality. Many reported that they had experienced outright discrimination or social or family difficulty when their actions did not match the traditional gender roles or heterosexual norms to which many in southern Utah subscribe. In the community and in the university, there were too few venues for students to discuss these issues. I decided that the class would tackle these topics with an unconventional approach to the art history of the twentieth century. I thought that if I could put their personal issues with gender and sexuality into a larger context, that would validate their experiences. Students might even begin having further conversations about gender and sexuality in our conservative community, closing the loop of critical pedagogy.

A typical class on twentieth century art would normally focus on the canon of that century, meaning the major works that appear in most textbooks on the topic. A good example of such a textbook is Arnason and Mansfield’s History of Modern Art (2013). Unfortunately, the canon of twentieth century art, like the canon of every other period in art history, contains very few works of art by women. “Most schools continue to run a male-centered curriculum, and a survey showed work by women artists makes up only 3%-5% of major permanent collections in the US and Europe” (Chicago 2012). I changed the focus of the course from the canon to works of art by women, who had also experienced discrimination on the basis of gender and sexuality.

The main text for the new and revised course was Whitney Chadwick’s Women, Art, and Society (2012). Using that book, we traced the development of women artists’ careers and experiences in the art world. Statements made by male artists, art dealers, and critics about women artists and their work were often very negative. Comments such as the following were typical of art critics throughout history. “The woman of genius does not exist. When she does, she is a man” (quoted in Chadwick 2012, 31). Many male artists in the early twentieth century viewed male sexual energy as the main source of their creative power, leaving no room for the creative power of women artists (ibid., 279). Chadwick tries to rectify the imbalance by focusing on works of art by women. My students reported that they liked Women, Art, and Society and found that it was an engaging text.[1]

This text sensitized my students to issues of gender. At the beginning of the semester, a few students reported that they had not witnessed discrimination based on their gender or sexuality. After two months of reading the Chadwick text, these same students described a shift in their view and reported seeing gender bias in action in their lives.

Early in the course, I was pleased with student engagement. The majority of the class members regularly contributed to in-class discussions. As I had anticipated, students wanted to discuss issues of gender in art and we periodically discussed issues of gender in the lives of the students.

Beyond the indirect measure of the quality and participation levels of class discussions, I had some further evidence that students were engaging with the course material. I set the first major assessment, a slide test, one month into the course. The results of the first major assessments in upper-division classes are often broadly scattered as students try to find their footing in the class, shown in the table below. In the Twentieth Century Art class, the results were still scattered, but the average was high. Moreover, several students’ written answers showed a level of art historical and gender analysis that went beyond class discussions and assigned reading material. This demonstrated a level of student engagement I had not previously seen at that early stage of the semester.

In the second month of the course, I travelled to New York to attend THATCamp CAA, where I also visited The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). At MoMA, I was most interested in seeing works of art from the early Modern period in the exhibition Inventing Abstraction, 1910-1925, which overlapped with the content of my Twentieth Century Art class. At the entrance to the exhibit, there was a large wall showing the social connections between Early Modern artists. This data visualization is reproduced in the exhibition’s interactive website, with photos of the artists and short biographies, and explained in The Modern Art Notes Podcast (Green and Dickerman 2013). I knew that the interactive online material would interest my students and I was interested in this example of Phase Three digital art history (Baca and Helmreich 2013).

My excitement about the MoMA visualization was reinforced by a talk I heard a few days later at THATCamp CAA. Paul B. Jaskot (2013) spoke about “Digital Visualizations as Art Historical Research: The Question of Scale.” Jaskot works on the Spatial History Project in the area of Holocaust Geographies. I was intrigued by how data visualizations gave him insight into the building activities at concentration camps, insights he had not gained through conventional study.

Ted Underwood (2013) has had similar insights, but claims that his colleagues in English literature “just don’t think it’s plausible that quantification will uncover fundamentally new evidence, or patterns we didn’t previously expect.” I think it is fair to say that many art historians would agree with Underwood’s colleagues. Underwood employs text mining in his work, a new methodology that uses computers and algorithms to analyze large bodies of texts. He asks a simple question of literary history, for which there are no answers in current scholarship, and shows how text mining can begin to answer the question. Using data-driven methodologies, he argues, scholars can make new discoveries in the humanities that can reshape our understanding of our disciplines.

Underwood’s work is the literary equivalent of Baca and Helmreich’s Phase Five. Jaskot’s work is part of Phase Three digital art history. It is at this phase that digital tools no longer serve as organizational assistants, but as real drivers of research outcomes. If only scholars could see their work represented differently, not as an extensive series of notes but as data visualizations, they could understand their work differently.

Before attending THATCamp, I did not think about my academic work as data collection or interpretation. I thought of my work, as a medieval art historian, as a matter of identifying and connecting written sources with works of art in a conventional way using my memory. I saw how reliance on my memory was a limited method, as I forgot important details, only to rediscover them later. I was primarily trying to hold tables of information in my mind and making only minimal use of tables in spreadsheets.

As a graduate student, I saw many of my peers approaching humanities research in the same way. I thought about my work in this conventional way even though I regularly used and created lists and tables in the process of research. I was using these tools in a Phase Two way, as organizational assistants, instead of in a Phase Three way, to help me reach new conclusions. My computer scientist husband even helped me create a diagram for my PhD dissertation, technically a data visualization. This visualization summarized my research but did not enhance it. When I heard Jaskot’s talk, I realized that I was missing out on a new and interesting approach to art history. I had previously used technology to record, organize, and even represent my work as part of a larger conventional framework. I had not used technology to help me better understand my work or to help me draw new conclusions.

After visiting THATCamp and MoMA, I was interested in seeing if data visualizations could help my students further engage in the course content. I hypothesized that through research and using graphics to visualize their research, I could help my students better understand gender bias in art history. They were already aware of it, having learned about it through our textbook, but I wanted to see if they could further internalize these lessons and detect it on their own. The data visualization would be the visible proof of their conclusions.

I returned to my Twentieth Century Art class and showed them the MoMA visualization. Fully immersed in Chadwick’s book, my students quickly noted that few female artists were included, even though the New York Times reviewer, Roberta Smith, praised the show for its inclusion of female artists (Smith 2012). My students counted a total of 88 artists and only 10 were women. They were not as impressed with the gender balance of the exhibit.

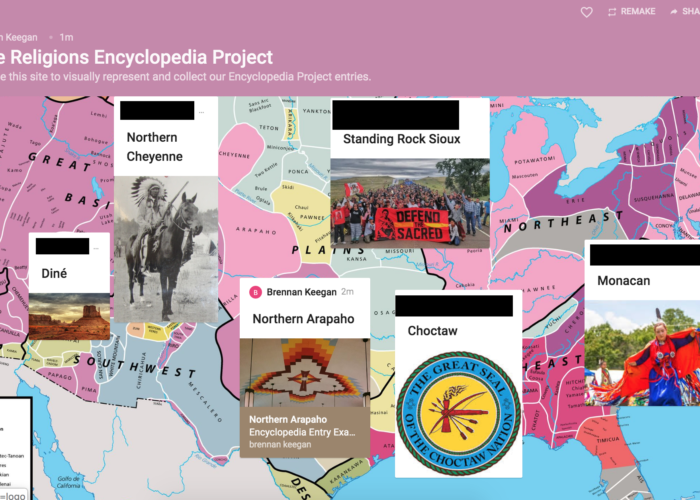

At this point in the semester, we were anticipating another major assessment. In the middle of the semester, I typically let the upper-division students collectively set the essay, while I make the rubric. The students decided to create their own visualization in response to the MoMA one. The student data visualization would show the social connections of women artists to other artists (men and women) from about 1910 through to the 1970s. Each of my fifteen students chose a woman artist covered in Women, Art, and Society, investigated their social circles, and wrote a brief biography.

To create the visualization, each student entered their artist’s social connections into a spreadsheet, pictured below. They used Google Docs because of the ease of sharing and editing as a group. The names of the women artist are in the first column and each of their artistic friends or acquaintances are in the columns to the right. Each individual’s gender is labeled on the spreadsheet, and the sexual orientations of our fifteen primary individuals are also labeled (straight, lesbian, bisexual). Primary individuals are also numbered, both in the first column and wherever else they appear on the spreadsheet.

In creating the visualization, we were trying to figure out how women artists worked and socialized compared with the men, who met and socialized with each other in clubs and cafés. The men directly influenced each other’s work, inviting each other to their studios. These social relationships became the means by which artistic influence spread. Women artists sometimes participated in these circles, often as partners or spouses of male group members.

We wanted to know if women had parallel artistic networks, meeting together in clubs and cafés, or if they were they isolated from each other. In Women, Art, and Society, Chadwick discusses female artists’ relationships to major movements in the twentieth century. Some women clearly worked independently, such as Romaine Brooks, and rejected the influence of the larger movements that did not accept women. Some worked within movements but struggled to have their work accepted on its own merits, as was the case with Lee Krasner who was married to the superstar Jackson Pollock. We wanted to understand if and how women artists worked with each other and hoped that a data visualization would offer insight into this question.

Even though this assessment involved writing an essay, an activity that does not normally excite students, the level of student engagement increased with the visualization component. I think that the prospect of creating a digital tool was an exciting and novel idea for my arts and humanities-focused students. They demonstrated their increased engagement in a variety of ways. Essay instructions always suggest that students use the library, library databases, and interlibrary loan to find appropriate readings for essays, but students rarely do these things or only do the absolute minimum. For this assessment, many students in the class interlibrary loaned books, all of them used the physical library, and all of them used library databases. I know that they did these things because we dedicated some class time to working on this project and students brought the library and interlibrary loan books with them to class. After reading these outside resources, students shared a number of amusing stories and information that they thought would interest the rest of the class. One student came to class and shared the exhibition reviews she had found on the New York Times website, both of contemporary and historical exhibitions. In the end, several students wrote essays that were in excess of twelve pages, above and beyond the essay requirements.

One problem that students encountered was that the secondary literature mainly discussed women’s artistic production in relation to men’s artistic production. Secondary sources were quick to point out meetings between a female artist and a more famous male artist, but few authors were interested in detailing relationships between female artists, failing a kind of art-historical Bechdel test (Stross 2008). The Bechdel test is a list of three questions that are normally applied to works of fiction to determine whether or not the work of fiction shows significant gender bias. So much of art history, as my students discovered, reveals gender bias and skewed the results for the project.

Students reported that some of the secondary sources they encountered fell into typical traps of interpreting female artists’ work in relation to their biography while ignoring larger social and political contexts (Chadwick 2012, 302). One student researching Georgia O’Keeffe came to the conclusion that views on the artist’s sexuality varied widely. Male authors tended to think she had lesbian relationships, where female authors came to other conclusions. Through these discussions, I saw my students demonstrate a depth of critical thinking I had not previously seen in my upper-division classes.

This project ended at the end of the semester, and left little time for students to draw larger conclusions about patterns of interaction. Nevertheless, we did get to see the interactive data visualization. One of my students was working on an Integrated Studies degree with Art and Visual Technologies. He used the spreadsheet and Flash to create the new data visualization, pictured below.

It is not as fully interactive as the MoMA visualization, but it’s well-developed for a class project. The gray links are our fifteen primary individuals and the colored lines represent the social connections between artists, with each artist having her own color. If you click on one of the gray links, you can see all of other artists that that person knows. Each individual on the chart has a blue or pink bar next to their name to indicate their gender.

Like many undergraduate projects, it has its problems, including a wide focus, incompleteness, too many spelling errors, mistaken gender caused by unfamiliar French names, and the repetition of the blue/pink gender colors in the line colors. Nevertheless, it was an instructive exercise and my students expressed pride in their contributions and in the resulting visualization. I think that the experience affirmed their ability to conduct research in art history and to engage in meaningful conversations about gender, which was a direct result of the application of critical pedagogy.

In using critical sources on data visualization to evaluate the class project after the semester, there are some clear problems. Jeffrey Heer and Ben Shneiderman (2012) created “a taxonomy of tools that support the fluent and flexible use of visualizations,” which outlines goals, methods, and skills sets necessary for different kinds of projects. Their article serves as a kind of guide book and rubric for data visualization projects. First, we attempted to visualize the entire data set in a single visualization, pictured above. This resulted in a visual mess that makes the larger visualization difficult to use, although this flaw is present in the initial MoMA visualization. It does allow users to select a single artist and filter out the rest, but does not offer other types of filters, as suggested by Heer and Schneiderman. The lack of filters and different views is limiting, as the visualization does not present clear patterns to the viewer.

It is telling that in a visualization attempting to understand the relationships between women artists, there is still an overwhelming amount of blue. This study did detect one female artist network, which involved several female artists living in Mexico, including Remedios Varo, Leonora Carrington, and Kati Horna. Female artists living in Paris knew each other, but the male-dominated artistic groups formed the focal point of artistic and social activity. It would have been possible to show this visually with additional filters that showed the geographic locations of female artists and their locations over time. I am also certain that a better-executed project could show further patterns that were not addressed in the scholarship on these women. This would have allowed the class to fully achieve Phase Three digital art history.

Students learned that the women we studied were generally connected to lots of other male artists, but not necessarily to many other women. Louise Bourgeois was the best-connected woman artist, closely followed by Remedios Varo, who is still relatively unknown. Perhaps Varo was disadvantaged in art history texts by having a higher percentage of women contacts. It would be possible to build on this project, correcting the existing errors and expanding the number of women artists included. This would allow a more thorough exploration of the relationships between women artists and would lead to clearer conclusions.

The project uncovered a lot of sexual scandal: heterosexual affairs, including those with male artists, homosexual affairs, sham marriages, and incest (thank you, Claude Cahun). Still, students revealed a lot of holes in scholarship, especially with Sonia Delaunay and Remedios Varo. Undergraduates often think of scholarship as complete, but my students now know that its not. They learned about the research process, the benefits of visualizing data, biased scholarship, and the problems of gender in the twentieth century.

At the end of the semester, many of the students reported that they thought about gender and twentieth century art differently than they had previously, that they had engaged in transformative learning. Specifically, many reported being more sensitive and aware of issues of gender. One student reported that she no longer assumed that all artists are or were heterosexual. Another student is constructing a senior project that addresses gender and the arts. A third student reported being unhappy with the secondary material on his artist, Meret Oppenheim, and is interested in researching and writing better material about her.

There were a number of successes with this class that I hope to repeat in future courses. Before the semester began, I knew that a group of students in the class were interested in issues of gender and as a result, I changed the focus of the class. Most importantly, the students were involved in shaping the class project, which stemmed from their own observations. Many students expressed interest in the digital and interactive nature of the project. When the students began the project, the outcomes were not clear. Students felt like they were engaging in real research instead of just learning prescribed course materials. All students reported positive experiences with this kind of research-based learning. Many students reported that they did not normally like working on group projects, but each student’s contribution formed a distinct and individual part of the larger project that allowed for full ownership of his or her part. This made group work more engaging and removed the stress that normally accompanies it. As a result of all of this, I will be looking to construct future class projects that are an intersection of digital humanities, course content, and gender studies.

Just as Underwood (2013) suggests that we “don’t already know the broad outlines of literary history,” I would suggest that we don’t already know the broad outlines of art history, in part because of gender bias. Students learned this first from their textbook and then applied their knowledge to a research project, where a data visualization confirmed gender bias in the history of female artists and in the scholarship on them. In class, we talked about art history in terms of data, tables, quantities, and graphics in addition to the more traditional terms of social movements, stylistic trends, and pivotal figures. Art history is changing and adapting to new technology, but this transition will be faster and smoother if digital tools and methods are introduced in undergraduate classrooms and not just in scholarly inquiry.

Bibliography

Ames, Carole. 1992. “Classrooms, goals, structures, and student motivation.” Journal of Educational Psychology 84:261-271. OCLC 425487180.

Arnason, H. Harvard and Elizabeth C. Mansfield. 2013. History of Modern Art. Boston: Pearson. OCLC 828721991.

Baca, Murtha, and Anne Helmreich. 2013. “Introduction.” Visual Resources: An International Journal of Documentation 29 (1-2): 1–4. doi: 10.1080/01973762.2013.761105. OCLC 844360251.

Bromley, Hank, and Michael W. Apple. 1998. Education/Technology/Power: Educational Computing As a Social Practice. Ithaca, NY: State University of New York Press. OCLC 42855540.

Carlyle, Thomas. 1888. On Heroes, Hero-Worship and the Heroic in History. New York: Fredrick A. Stokes & Brother. OCLC 18009935.

Chadwick, Whitney. 2012. Women, Art, and Society. New York: Thames and Hudson. OCLC 21141190.

Chicago, Judy. 2012. “We women artists refuse to be written out of history.” The Guardian. October 9. http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2012/oct/09/judy-chicago-women-artists-history. OCLC 60623878.

Committee on Increasing High School Students’ Engagement and Motivation to Learn. 2003. Engaging Schools: Fostering High School Students’ Motivation to Learn. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. OCLC 61521032.

Cuno, James. 2013. “Open Content, An Idea Whose Time Has Come.” The Getty Iris (blog). August 12. http://blogs.getty.edu/iris/open-content-an-idea-whose-time-has-come/.

Duggan, Bob. 2013. “What Would Digital Art History Look Like?” Big Think: Picture This (blog). April 16. http://bigthink.com/Picture-This/what-would-digital-art-history-look-like.

Freire, Paulo, Myra Bergman Ramos, and Donaldo Macedo. 2000. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 30th Anniversary Edition. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. OCLC 834096737.

Green, Tyler and Leah Dickerman. 2013. “Episode No. 60.” The Modern Art Notes Podcast. February 27. http://manpodcast.com/post/44160970344/episode-no-60-of-the-modern-art-notes-podcast.

Heer, Jeffrey, and Ben Shneiderman. 2012. “Interactive Dynamics for Visual Analysis.” Queue 10 (2). http://queue.acm.org/detail.cfm?id=2146416. OCLC 4809433462.

Hopkins, David. 2000. After Modern Art 1945-2000. New York: Oxford University Press. OCLC 43729118.

Jaskot, Paul B. 2013. “Digital Visualizations as Art Historical Research: The Question of Scale.” February 12. Paper presented at ThatCamp CAA, February 11-12, 2013.

Linnenbrink, E., and Pintrich, P. 2000. “Multiple Pathways to Learning and Achievement: The Role of Goal Orientation in Fostering Adaptive Motivation, Affect, and Cognition.” In Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation: The Search for Optimal Motivation and Performance, edited by Carol Sansone and Judith M. Harackiewicz, 195-227. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. OCLC 44852065.

McLean, Monica. 2006. Pedagogy and the University: Critical Theory and Practice. London: Continuum International Publishing. New York: Continuum. OCLC 229410256.

Meece, Judith L. 1991. “The Classroom Context and Student’s Motivational Goals.” In Advances in Motivation and Achievement, vol. 7, edited by Martin Maehr and Paul Pintrich, 7:261-285. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. OCLC 40489787.

Newmann, Fred M. 1992. “Introduction.” Student Engagement and Achievement in American Secondary Schools. New York: Teachers College Press. OCLC 25833147.

Nicholls, John G. 1983. “Conception of Ability and Achievement Motivation: A Theory and its Implications for Education.” In Learning and Motivation in the Classroom, edited by Scott Paris, Gary M. Olson, and Harold Stevenson, 211-237. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. OCLC 9575425.

Smith, Roberta. 2012. “When the Future Became Now: ‘Inventing Abstraction: 1910-1925’ at MoMA.” The New York Times, December 20. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/21/arts/design/inventing-abstraction-1910-1925-at-moma.html?pagewanted=all

Stross, Charles. 2008. “Bechdel’s Law.” Charlie’s Diary (blog). July 28. http://www.antipope.org/charlie/blog-static/2008/07/bechdels_law.html

Underwood, Ted. 2013. “We Don’t Already Understand the Broad Outlines of Literary History.” The Stone and the Shell (blog). February 8. http://tedunderwood.com/2013/02/08/we-dont-already-know-the-broad-outlines-of-literary-history/

[1]In the second half of the course, we read David Hopkins’ After Modern Art (2000). This text applies a more traditional, or masculine, approach to art history, which covers the canon with few references to women artists and their work. Unlike Chadwick, Hopkins references many ideas and historical events that he does not explain. Some students liked the change in style, but many reported that it seemed like the author was trying to pitch the material over their heads in an effort to show off his knowledge. Nevertheless, using the two different texts showed my students two different approaches to the same material. Next time I teach this class, I plan to assign parallel readings from both texts instead of reading them consecutively.

About the Author

Nancy Ross graduated from the University of Cambridge in 2007 with a Ph D in the History of Art. She is an Assistant Professor of Art History at Dixie State University in St. George, Utah. She led the TICE ART 1010 development team in 2011-12 and is the Contributing Editor for Medieval Art for Smarthistory at Khan Academy. She blogs about teaching art history at Experiments in Art History.