Introduction

Information Literacy (IL) is one of the defining concepts of academic librarianship. It influences core functions including reference, collection development and especially library instruction. However, the definition of IL is malleable and influenced by the proliferation of online resources, developments in information technology, and trends in academic publishing, all of which have dramatically altered research methods. In January 2016, the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL), a division of the American Library Association (ALA), adopted the Framework for Information Literacy (Framework) for Higher Education. Its six core concepts afford librarians maximum flexibility when teaching IL (American Library Association 2015). This adoption was shortly followed by ACRL rescinding the Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education (American Library Association 2000), which had served as the defining IL document for professional librarianship since 2000. The ACRL Framework defines IL as, “the set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning.” Moreover, the framework is based on interconnected core concepts with flexible options for implementation, rather than a set of prescriptive standards or learning outcomes.

The Library Media Resources Center (hereafter Library) at LaGuardia Community College, part of the City University of New York (CUNY) founded in 1971, maintains an active and evolving IL program that impacts reference services, library instruction, and credit-bearing courses. The latter is exemplified by LRC103: Internet Research Strategies, a one-credit, liberal arts elective offered by the Library; it has been offered since 2004, and IL is central to the course’s syllabus (Keyes and Namei 2010, 29). The course teaches students “analytical thinking, problem-solving, and information literacy skills necessary for academic research and digital citizenship” (LaGuardia Community College Catalog 2017-2018). Students receive one hour of face-to-face instruction each week, covering concepts (concept mapping, research question development, citation) and resources (subscription databases, digital images, digitized primary sources) central to developing IL. While LaGuardia is not unique in offering a credit-bearing IL course, a 2016 study concluded that only 19% of higher education institutions surveyed offer such courses (Cohen et al. 2016, 566). Due to this small percentage, credit-bearing IL courses present a relatively unique opportunity to teach IL to students. This is particularly true when compared to traditional library instruction sessions, which are typically one hour long and offered once each semester for select courses (e.g. English 101).

The following case study investigated the efficacy of IL pedagogy on undergraduate research in a section of LRC103 offered during the Spring 2017 semester at LaGuardia. More specifically, the study analyzed student success and sought to determine whether written reflection and practice strengthen IL skills, including the fundamental ability to develop a research question and thesis statement. In fact, the ACRL Framework recognizes the importance of research question advancement. As outlined in Research as Inquiry, research “depends upon asking increasingly complex or new questions whose answers in turn develop additional questions” (The Association of College and Research Libraries 2015). Developing research questions and formulating thesis statements are among the most challenging duties of a young researcher. From high school through undergraduate, students often have minimal experience conducting research. They may not know where to begin the research process and what steps are necessary (Fernando and Hulse-Killacky 2006, 103-104). Student frustration is exacerbated by the fact that typically IL instruction is one-shot guidance, given only once in a semester, making it difficult for a librarian to cover all that is needed. Can a semester long, credit-bearing course aid student success in research and improve IL skills? The instructors introduced several techniques to improve IL skills, and instructors evaluated three class assignments based on the college’s core competencies. Additionally, instructors collected and analyzed students’ written reflections of their progress and an end of semester survey as both qualitative and quantitative data. As a platform to post reflection, the authors implemented electronic portfolio (ePortfolio) practice for the course. Deeply embedded in LaGuardia’s academic culture, its current ePortfolio program utilizes Digication software in both pedagogy and assessment (LaGuardia Community College, “About ePortfolio”, 2017). All twelve enrolled students were eligible to participate, and eleven elected to take part in the study.

Literature Review

The following literature review reflects the goals of this study and is not intended to be comprehensive. Unlike conventional library instruction, the uniqueness of this study was that it examined students’ IL skills over the course of an entire semester. The research was empirical, using outcomes-based and affective analysis to study IL pedagogy. This case study expanded on the term project for LaGuardia’s LRC102, Information Strategies: Managing the Revolution, a credit-bearing course previously taught at LaGuardia, which called for an annotated bibliography, accompanied by a narrative of research where students describe the process used to find each item in the bibliography and explain its inclusion. In a study of LRC102, Fluk concluded that further research should be done into how research logs and journal writing affect student learning and how logs and journals should best be assigned (Fluk 2009, 50).

Colleges and universities have targeted the following learning objectives when creating or redesigning credit-bearing IL courses: developing research topics research questions, and thesis statements (Mulherrin, Kelley, Fishman, Orr 2004, 24; Frank and MacDonald 2016, 17). Broadly considered, the literature on measuring and assessing the impact of IL instruction on educational outcomes is varied, especially in the wake of the 2015 adoption of the ACRL Framework, which omitted specific standards, competencies, and learning outcomes. Examples from community colleges and/or credit bearing IL courses were sought for this literature review. Longitudinal studies of students at Hostos Community College, a CUNY school with comparable demographics to LaGuardia’s, and Western Georgia University demonstrated that students taking IL workshops and a credit-bearing IL course, respectively, resulted in higher graduation rates, higher pass rates on reading and writing tests, and higher cumulative grade point averages. The Hostos Community College study results determined that students taking IL workshops experienced a 35.3% graduation rate, compared with 9.8% for students who did not take the workshops. Additionally, students who completed the IL workshop passed the CUNY Proficiency Exams for Reading at a rate of 78.5% and for Writing at a rate of 73.5%; the students who did not take the workshops passed the exams at a rate of 57.6% and 47.2% (Laskin and Zoe 2017, 13-16; Cook 2014, 276-279). Similarly, University of Western Georgia concluded that overall graduation rates for students in the study who completed their credit-bearing IL course graduated within six years at significantly higher rates than those who did not, 56% versus 30% (Cook 2014, 277-278).

In their discussion of CUNY’s Critical Thinking Skills Initiative, Gashurov and Matsuuchi stressed the importance of IL for LaGuardia’s LRC103 course to ensure CUNY students are prepared for today’s competitive job market (Gashurov and Matsuuchi 2013, 70-71). The Critical Thinking Skills Initiative was in part a reaction to the financial crisis of 2007-2008, but LaGuardia’s commitment to IL can be traced back to 1991 when it began offering LRC102. As mentioned above, LRC103 was first offered in 2004 and is central to the Library’s IL program (Keyes and Namei 2013, 29). More recently, the Citation Project, a multi-institutional study on source usage in college writing, has concluded that students struggle with all aspects of citation and comprehending sources: summarizing, paraphrasing, and quotation, to name a few (Jamieson and Howard 2013, 125-126). Jamieson’s further research claims that IL pedagogy based on the ACRL Framework, more so than the older ACRL IL competencies, may help students better understand their sources (Jamieson 2017, 128-129), which matches the goals of the present study.

At the postsecondary level, ePortfolio use has matured from a tool to document professional development to a web portal for accessing work, tracking academic growth, and planning a career, acting as a record of skills, achievements, and learning (LaGuardia Community College, “Introduction: What is an ePortfolio?”, 2017). Nevertheless, academic libraries have been slow implementing ePortfolios as compared to other campus departments, due in part because IL instruction is typically offered once per semester, in one class, and tailored to a specific assignment. However, a few have administered ePortfolios as a method of improving research and critical thinking. In 2008, Three Rivers Community College designed a plan whereby students searched for scholarly articles and then discussed the techniques used to retrieve them in a written reflection of their online learning experience posted into their ePortfolio (Florea 2008, 424-425). More recently, in collaboration with another campus department, the Otis College Library in 2014 created a research assignment that students uploaded to their ePortfolio and that instructors graded using the college’s core competencies (Giuntini and Venturini 2014, 11-15).

Methods and Analysis

Instructed by the authors, the LRC103 class in this study met weekly in one-hour face-to-face sessions for twelve weeks in the spring 2017 semester. Class lessons and assignments aimed to advance student research ability by fostering IL skills. The first class lesson introduced fundamental database tools, such as subject headings and subject term delimiters, to narrow a broad topic down to specific issues and subjects. The technique helps students comprehend article indexing and focuses student research to an elemental concept. For example, a search for “global warming” in a standard database yields thousands of results. However, the recommended subject headings “global warming & politics” and “global warming & the environment” generates a more manageable list. Subject term delimiters, custom to databases, refine this list to specifics. The assignment accompanying the lesson sought to discover if database tools support critical thinking development. First, it prompted students to write a 200-word description of an article found in a research database, summarizing the author’s viewpoint and any evidence provided in their argument. Next, it asked students to frame and develop a research question for further inquiry related to the article’s topic. Lastly, in a reflection, students explained if writing the summary helped them review and disseminate the material to forge a unique and specific area to research (See Appendix A).

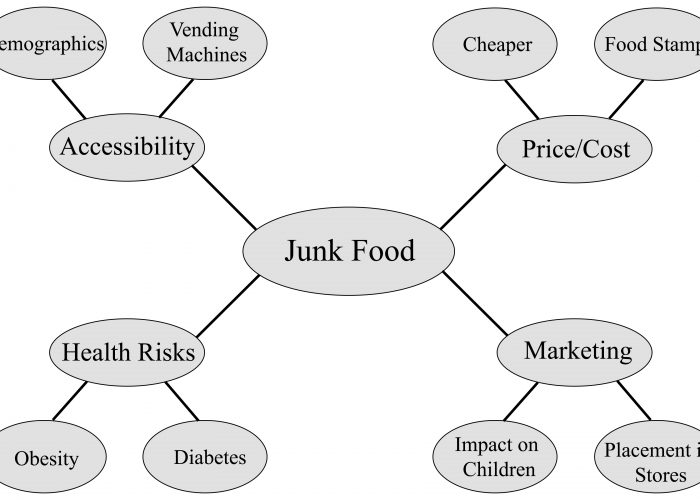

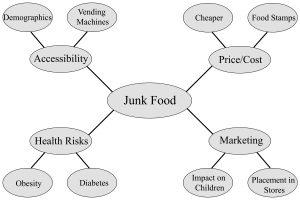

The second lesson demonstrated use of an online encyclopedia, illustrating the expansive subject list available. Then, students read an article on a select topic and gathered keywords. Students made note of words that they felt were key to understanding the topic. The final part of the lesson introduced concept maps, a graphical tool for organizing and representing knowledge. Concept maps break down a topic into related issues, with details or examples for each issue (Appalachian State University: Belk Library and Information Commons 2017). Words are usually “enclosed in circles or boxes of some type, and relationships between concepts [are] indicated by a connecting line linking two concepts” (Novak and Cañas 2008). Using the words marked in the encyclopedia article, students created concept maps. Following this lesson, students completed the second assignment, the class midterm, which asked them to develop a topic and their own argument using methods learned in class. Students had the option to use the first assignment topic or to select a new one. Suggestions provided were affordable housing, human trafficking, and junk food. The instructors recommended that students first break down the topic using a concept map and then develop a related viewpoint or argument from one issue or concept in the map. For the first part of the midterm, each student needed to find one scholarly article in support of their thesis argument and give a thirty-second, persuasive pitch in class to argue their viewpoint. In their ePortfolio, they provided an MLA citation of the article and wrote a one-paragraph description, which included their thesis statement, an explanation of the topic, and the reason they selected it. In the second part of the midterm, students supported their arguments with two additional scholarly articles, one in support of their thesis and one counterpoint. To showcase their evidence, students created an annotated bibliography. For this class, an annotated bibliography referred to a list of resources, each with a reference citation in Modern Language Association (MLA) style and a summary or evaluation (Stacks, et al. 2017). Finally, in a one-paragraph reflection, students considered whether or not the lesson and midterm helped them narrow down their research and develop their arguments (See Appendix B).

Figure 1: Sample concept map of ‘junk food’ and its related issues, complete with details and examples of each. Concept maps break down a topic or main idea into related issues or concepts, and onto details or examples.

The class final required students to explain the most successful ways to develop a research question based on skills learned in class, in either a five-minute video, five-minute audio recording, or Microsoft PowerPoint presentation of at least five slides. As part of their work, they needed to describe if they will use the skills learned in other classes and assignments (See Appendix C). Lastly, an eight-question survey given to students on the last day of class provided a means to quantitatively measure success of class pedagogy. It was optional and anonymous (See Appendix D).

To evaluate student work, the instructors created an assessment rubric based on one of LaGuardia’s four core competencies, inquiry and problem solving. Inquiry and problem solving is comprised of the ability to design, evaluate, and implement a strategy or strategies to answer an open-ended question or achieve a desired goal. Students advance this competency by framing an issue, gathering evidence, analyzing material, and formulating conclusions (LaGuardia Community College, “Outcomes Assessment”, 2017). Based on this framework, the instructors assessed student work on ability to: 1) analyze and synthesize research material, 2) formulate conclusions to develop research questions and thesis arguments, and 3) understand and integrate IL skills.

Therefore, students who received a letter grade of A on an assignment demonstrated proficient IL skills. A letter grade of B signified competent skills, a C denoted developing skills, and a grade under C deemed the student a novice. In addition to a grade, the instructors also provided constructive feedback to advise students how they could improve their work.

Since each of the three assignments weighed differently towards the student’s final grade, all grades in this article were proportioned based on one-hundred points. For example, if a student assignment received fifteen out of twenty points, the grade was seventy-five, or a C, and the student demonstrated developing IL skills. In addition to grades, the authors analyzed student reflections to draw conclusions on student progress in class and uncover what pedagogies best helped.

Results

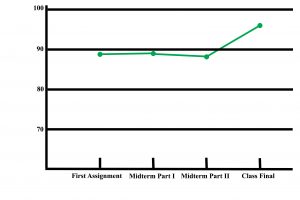

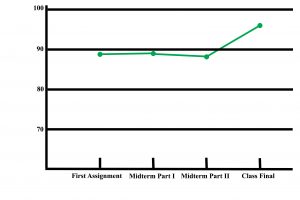

In the first assignment, seven students demonstrated proficient skills, two had competent skills, one showed developing skills, and one was a novice, for a class average of 89.5. In a combined midterm grade, six students were proficient, three were competent, one was developing, and one was a novice, for a class average of 89.1. While student work remained at the competent stage in the first two assignments overall, performance improved to proficient on the final, for a class average of 96.7, as students displayed a deeper understanding of research concepts and were able to express them in presentation and reflection.

Figure 2: The line graph shows student progress in each of the four class assignments based on 100 points. The class average changed from 89.5 in the first assignment, to 89.1 in the midterm, and to 96.7 in the final exam.

Student obstacles in the first two assignments were inability to narrow down a topic in a focused research question and lack of solid arguments in thesis statements. For example, the research questions “are artists overly-hypocritical of other artists’ work for biased reasons?” and “is society to blame for engraving the idea that men were/are much more superior than women?” were not open-ended but rather took a position. Similarly, the question “what are the causes of animal extinction?” could be improved by selecting a specific animal or animal habitat.

Conversely, the question “how did Edgar Allan Poe’s life affect his writing?” was open-ended and focused but could be revised by concentrating on one event in Poe’s life. In the midterm, the statement “[weight gain and disease due to junk food intake] has been a problem that has been occurring for many years and there is a solution to the problem” was not a solid thesis but rather only stated there was a solution. On the other hand, the thesis “college students should get free tuition” suggested a solution but didn’t offer any justification. Lastly, the complete statement “due to the highly addictive nature of junk food and food manufacturers reluctance to alter their products or marketing, only some type of severe intervention will improve the quality of the food made in America and lessen the rates of obesity and diabetes” demonstrated a strong thesis and highlighted student learning progress, acknowledging the complexity of the issue while taking a side.

Another student challenge was inability to follow directions. Some failed to provide an opposing viewpoint in the annotated bibliography while others placed too much opinion in a summary. For example, one student wrote: “[with this article] I came up with many more questions than answers.” Still, another student didn’t provide summaries at all, but rather simply listed citations. While most students explained class pedagogy well in the final exam, some didn’t explain it thoroughly enough or didn’t provide examples in relation to assignments. For example, one student simply added a bullet list on the final to support the best ways to successfully develop a research question rather than explaining them. Several students neglected to distinguish between their assignments, making it uncertain where one assignment ended and another began.

Student reflection on progress was generally positive. In fact, a student suggested that one skill learned in the course was the “ability to think critically about information found” in research. In a first assignment reflection, a student commented, “after laying out all the information and my personal thoughts, I felt that I had a better understanding of the article, making it easier to develop my own research question.” Another submitted that in summarizing the article they “started to really absorb the information.” In midterm reflections, concept maps most successfully aided student success. One wrote: “[concept maps] helped narrow down the possibilities of creating research questions and starting my search with general keywords where I could find articles.” Another added: “it allows me to develop a cohesive structure for the ideas that I want to present and analyze the relationship between the ideas and the main concepts as well as how the ideas complement the concept.” Reflections on the annotated bibliography were also positive and suggested that students not only developed IL skills but planned to integrate concepts in other classes. “It breaks down the articles and picks apart key details,” one student suggested. Another delved deeper, adding that they will retain class work for reference in case they need citation assistance: “It will come in handy in classes where the professor prefers MLA8 style.”

Results of the final survey indicated that students were generally pleased with pedagogy and instruction provided, and they generally agreed that reflection aided research. All participants identified both making a concept map and using fundamental database tools as the most useful approaches to develop research questions. Written feedback was also primarily positive, indicating satisfaction in semester-long IL course. One student said: “I thought this class was really helpful and should have been one of the first classes that I took here at LaGuardia because it helped a lot with writing research papers and finding information.” Another said: “the topics helped with my knowledge and expanded my experience with different databases.”

Discussion

This semester-long case study provides an argument that the course helped students develop IL skills and that further research is warranted. Its limitations were that it was conducted on one class with a low enrollment. The ideal case is either a class with a larger enrollment in a longitudinal study or a comparative study of two class sections, one section using reflection as a learning practice and one without. The authors hope their work can serve as a framework for subsequent studies at LaGuardia and elsewhere to foster IL skills.

While grade success may suggest that students gained academic proficiency in the class, student reflection provides the best argument for credit-bearing IL courses. In their own words, students reflected how they integrated key concepts into their academic work that will be used in both future classes and in life. Students suggested the concept map as the key method to success in the course, making this graphical tool a vital part of library instruction. It allows students to break down a topic and make conclusions about what area to research. Reflections also provided an opportunity to connect class pedagogy to lifelong learning. In a final study feedback response, a student summarized the need for semester-long instruction, and that the course should have been one of the first classes that they took at LaGuardia to guide their research and IL skills.

Conclusion

Student achievement in the course demonstrates that when applied in a credit-bearing IL course, strong IL pedagogy and effective use of instructional technology aids and enhances student success. Students generally felt that the IL skills they developed in LRC103 can be utilized in other courses. However, for IL instruction to be successful, strong pedagogy is tantamount in concert with thoughtful implementation of instructional technology, in this case ePortfolio. Ideally, credit-bearing IL instruction would be offered when a student begins college. The following is a list of considerations when making IL pedagogy decisions generally and possible next steps for LRC103.

Prepare useful lessons and select appropriate assignments

Nothing replaces solid pedagogy. Constructive assignments foster student learning. The lesson on concept maps as a method to develop focused research topics spurred the greatest jump in level of the inquiry and problem-solving competency. Assignments that encouraged metacognition — Student midterm reflections and answers in the final survey — also suggest concept maps as a useful method to help narrow a research topic.

Instructional technology best practices

There is no ideal course management platform. An easy-to-use format where material and information can be added and retrieved is ideal. Naturally, the library may not be the final voice in what platform software a campus uses. However, it can suggest recommendations based on feedback from students. It is recommended that class time should be allotted at the beginning of the semester for course software instruction. Subsequent instruction should also be considered at the time assignments are introduced or prior to due dates, in order to model best practices.

Finally, organization and maintenance of a platform is key to success, and, as with any electronic tool, ePortfolio is only as good as the effort put to its use. Things to avoid are unlabeled assignments, irrelevant material, uploads that require additional software, broken links, and incomplete evidence.

Gather Qualitative Data

Since LRC103 is a one-credit course with modest enrollment, the sample size will remain small thereby limiting the impact of quantitative data. Gathering more qualitative data in the form of written reflections and student interviews could benefit the ongoing development of IL pedagogy for librarians teaching this course. Regardless of the instructional technology utilized, student reflection and metacognition are essential for credit-bearing IL instruction courses.

Collaborate with other academic departments

To promote library resources and services, collaborate with other departments. The English department is one option. Developing a research question, finding information, formulating a thesis, and then writing an argumentative paper are the basis for a common English class paper. Beyond English, there are ample opportunities incorporate IL pedagogy in various disciplines: history, social sciences, and STEM programs. An essential feature of the ACRL Framework is its flexibility. “Research as Inquiry,” “Information has Value,” and “Searching as Strategic Exploration,” three of the six frames, are central to academic research regardless of discipline. For example, LaGuardia’s Library has collaboratively developed a curriculum of one-hour, one-shot library instruction sessions for the college’s First Year Seminars, introductory, discipline-specific courses that provide remediation (LaGuardia Media Resource Center, FYS Library Instruction, 2017). The curriculum maps from LaGuardia’s core competencies (e.g. global learning, integrative learning) to related concepts in the ACRL Framework and library instruction lesson plans for each seminar; the entire curriculum is hosted on the LibGuides platform. This type of collaboration could be expanded to the Library’s credit-bearing courses to incorporate discipline-specific IL pedagogy. One way to incorporate is participation in LaGuardia’s Learning Communities, which pair two or more courses around a common theme (LaGuardia Community College, “Liberal Arts Learning Communities,” 2018). These learning communities could give LaGuardia librarians an opportunity to teach discipline-specific versions of LRC103 that would implement the conclusions from this case study and supporting research.

Bibliography

American Association of Colleges and Universities. 2017. “High-Impact Educational Practices.” http://www.aacu.org/leap/hips.

Appalachian State University: Belk Library and Information Commons. 2017. “Concept Mapping.” Accessed on October 9, 2017. https://library.appstate.edu/research-help-guides/video-tutorials/concept-mapping.

The Association of College and Research Libraries. 2010. “Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education.” Accessed on October 9, 2017. https://alair.ala.org/handle/11213/7668?show=full.

The Association of College and Research Libraries. 2015. “Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education.” Accessed on October 9, 2017. http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework#introduction.

Beagle, Donald. 2010. “The Emergent Information Commons: Philosophy, Models, and 21St Century Learning Paradigms.” Journal of Library Administration 50, no. 1: 7-26.

Bryant, Lauren H. and Jessica R. Chittum. 2013. “ePortfolio Effectiveness: A(n Ill-Fated) Search for Empirical Support.” International Journal of ePortfolio 3, no. 2: 189-198.

Clark, J. Elizabeth, and Bret Eynon. “E-portfolios at 2.0–Surveying the Field.” Peer Review 11, no. 1 (2009): 18-23.

Cohen, Nadine, Liz Holdsworth, John M.Prechtel, Jill Newby, Yvonne Mery, Jeanne Pfander, and Laurie Eagleson. 2016. “A Survey of Information Literacy Credit Courses in US Academic Libraries.” Reference Services Review 44, no. 4: 564-582.

Cook, Jean Marie. 2014. “A Library Credit Course and Student Success Rates: A Longitudinal Study.” College & Research Libraries, 75, no. 3: 272-283.

Duvall, Sara, and Peter Pasque. 2013. “The 21st Century Literacies Gap: A Case for Adoption of the Student Learning Networks Model Grades 9-16.” Public Services Quarterly 9, no. 1: 70-80.

Fernando, Delini M., and Diana Hulse-Killacky. 2006. “Getting to the Point: Using Research Meetings and the Inverted Triangle Visual to Develop a Dissertation Research Question.” Counselor Education & Supervision 46, no. 2 (December): 103-115.

Florea, Mona. 2008. “Using WebCT, Wiki Spaces, and ePortfolios for Teaching and Building Information Literacy Skills.” Journal of Library Administration 48, no. 3-4: 411-430.

Fluk, Louise. 2009. “The Narrative of Research as a Tool of Pedagogy and Assessment: A Literature Review.” In-Transit: The LaGuardia Journal on Teaching and Learning 4: 40-56.

Frank, Emily and Amanda MacDonald. 2016. “Eyes Toward the Future: Framing For-credit Information Literacy Instruction.” Codex (2150-086X) 4, no. 4: 9-22.

Giuntini, Parme and Jean-Marie Venturini. 2014. “Learning by Doing: Using Eportfolios for Assessment at Otis College of Art and Design.” Library Hi Tech News 31, no. 7 (August): 11-15.

Guder, Christopher. 2013. “The Eportfolio: A Tool for Professional Development, Engagement, and Lifelong Learning.” Public Services Quarterly 9, no. 3 (July-September): 238-245.

Hampe, Narelle, and Suzanne Lewis. 2013. “E-portfolios Support Continuing Professional Development for Librarians.” Australian Library Journal 62, no. 1: 3-14.

Hsieh, Ting-Chu1, et al. 2015. “Longitudinal Test of Eportfolio Continuous Use: An Empirical Study on the Change of Students’ Beliefs.” Behaviour & Information Technology 34, no. 8 (August): 838-853.

Jamieson, Sandra. 2017. “What the Citation Project Tells Us About Information Literacy in College Composition.” In Information Literacy: Research and Collaboration across Disciplines. Perspectives in Writing Series. Edited by Barbara D’Angelo, Sandra Jamieson, Barry Maid, & Janice R. Walker, 119-143. Fort Collins, Colorado: WAC Clearing House & University Press of Colorado, 2017.

Jamieson, Sandra, and Rebecca Moore Howard. 2013. “Sentence-Mining: Uncovering the Amount of Reading and Reading Comprehension In College Writers’ Researched Writing” in The New Digital Scholar: Exploring and Enriching the Research and Writing Practices of NextGen Students. Edited by Randall McClure and James P. Purdy, 111-133. Medford, NJ: American Society for Information Science and Technology.

Kehoe, Ashley and Michael Goudzwaard. 2015. “ePortfolios, Badges, and the Whole Digital Self: How Evidence-Based Learning Pedagogies and Technologies Can Support Integrative Learning and Identity Development.” Theory into Practice 54, no. 4: 343-351.

Kuh, George and Carol Geary Schneider. 2008. High-Impact Educational Practices: What They Are, Who Has Access to Them, and Why They Matter. Washington, DC: American Association of Colleges and Universities.

LaGuardia Community College. 2017. “About ePortfolio.” Accessed on October 9, 2017. http://www.eportfolio.lagcc.cuny.edu/about/.

LaGuardia Community College. 2016. “Fast Facts.” http://www.laguardia.edu/About/Fast-Facts/.

LaGuardia Community College. 2017. “Frequently Asked Question.” Accessed on October 9, 2017. http://www.laguardia.edu/ssm/faq.

LaGuardia Community College. 2017. “Introduction: What is an ePortfolio?” Accessed on October 9, 2017. http://www.eportfolio.lagcc.cuny.edu/students/default.htm.

LaGuardia Community College. 2018. “Liberal Arts Learning Communities.” Accessed on March 6, 2018. http://www.laguardia.edu/clusters/.

LaGuardia Community College. 2017. “Outcomes Assessment.” Accessed on October 9, 2017. http://www.laguardia.edu/Assessment/Resources.

LaGuardia Community College, Library Media Resources Center. 2017. “First Year Seminar Curriculum Map.” Accessed on March 6, 2018. http://guides.laguardia.edu/fys.

Laskin, Miriam and Lucinda Zoe. 2017. “Information Literacy and Institutional Effectiveness: A Longitudinal Analysis of Performance Indicators of Student Success.” CUNY Academic Works. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ho_pubs/60.

Mulherrin, Elizabeth, Kimberly B. Kelley , Diane Fishman & Gloria J. Orr. 2004. “Information Literacy and the Distant Student.” Internet Reference Services Quarterly 9, no. 1-2: 21-36.

Novak, Joseph D. and Alberto J. Cañas. 2008. “The Theory Underlying Concept Maps and How to Construct and Use Them.” Florida Institute for Human & Machine Cognition. Accessed on October 9, 2017. https://cmap.ihmc.us/docs/theory-of-concept-maps.

Osborn, Jennifer. 2009. “E-Portfolios: Personal Learning, Professional Development.” Incite 30, no. 6: 18.

Stacks, Geoff, et al. 2017. “Annotated Bibliographies.” Purdue Online Writing Lab. Accessed on October 9, 2017. https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/614/01.