“Internet searching doesn’t hold a candle to that visceral feeling of an old primary document. All of my senses were triggered on this archive visit, and I was only there for half a day. I would like to return to the archive—this archive, any archive—without an assignment or mission attached and just have some fun exploring.” —Elyse Orecchio[1]

“During our visit to Tamiment Library, I was moved by the fact that each box contained individual memories of an American volunteer in the Spanish Civil War. I wondered how much of one person’s life could fit in these boxes, and how these documents could help narrating the friendships among young soldiers, the making of improvised families, the experiences of the displaced children, and how some these lives might have survived the war. I wondered, finally, how much legacy can these archives preserve?” —Marcelo Agudo

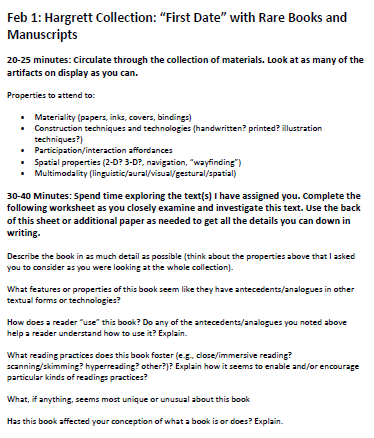

In a class session announcing a visit to the Hunter College Archives, several students in a class of juniors and seniors admitted that they had never even been inside the Hunter College Library—or any library. We might all shudder at the thought, but it is quite common for students to have no reason for entering a physical library or speaking with a librarian face to face. It is not that students Google everything: they have extensive remote access to scholarly journals and primary sources through electronic databases, and digital holdings now outpace physical holdings at libraries. Furthermore, librarians are available through digital platforms to assist students with their research. As student reflections from our courses show, the experience of entering a library, working with physical primary sources, and interacting with librarians face-to-face became a positive practice that not only introduced students to a new method and approach to research, but also resulted in new attitudes towards libraries, librarians, and the relevance of institutional memory.

The central question of this essay focuses on the role of students in institutional memory: what does it mean for undergraduates to do the work of narrating memory? Here we elaborate our archival research assignments: María Hernández-Ojeda’s Narrating Memory assignment taught in her courses on Spanish literature, and Wendy Hayden’s Rhetorical Reflections assignment, taught in her courses on rhetoric and writing. We both assigned undergraduates at Hunter College-CUNY to perform archival research in physical archives and report on that research on digital platforms (all WordPress based sites): Narrating Memory, Rhetorical Reflections in the Hunter College Archives, and Archival Research and Rhetoric. Iris Finkel, Reference and Instruction Librarian at Hunter College, redefined the role of the librarian in classroom instruction as she assisted students and faculty with research assignments in both physical and digital archives and used her digital humanities expertise to help students and faculty understand the norms and creative approaches to digital presentation. Although the three of us began these projects separately, here we bring them together in order to illustrate the theme of connection in teaching with archives: connections between our goals for our projects; between students and their research projects; between the past and the present; between students, faculty, and librarians; and between the physical act of archival research and the digital writing to record that research.

Over twenty years ago, Randy Bass (1997) promoted active learning pedagogy that incorporated primary sources and new technologies. Bass illustrated how new technologies facilitated engagement and fostered collaboration among students, using examples of assignments where students interacted with “electronic primary source archives (on the World Wide Web, or CD-ROM)” (1997, 15). Through hypertext, then a revolutionary new feature of interactive media, students were readily able to explore outside the source to find other meaning-making connections. Using technologies such as email, listservs, electronic discussion lists, and teleconferencing, students discussed primary sources outside the classroom. Students collaborated, made new connections in the material, and communicated knowledge that added a different perspective. Students moved from knowledge “consumers to producers” (Bass 1997, 33). We show how emerging technologies continue to empower student voices.

Recent scholarship shows that more teachers are assigning physical archival research to undergraduates, a trend Hayden (2017) has called “The Archival Turn’s Pedagogical Turn.” Students have been assigned to research in institutional archives (Brand, Kendall, and Sanders 2012; Johnson and Mulder 2011), community archives (Grobman 2017; Mutnick 2018), and in larger repositories (Devos et al. 2012; Mock 2015). In addition, archivists are reaching out to teachers to form partnerships with specific classes, such as the Brooklyn Historical Society’s TeachArchives.org (Golia and Katz 2018). Recent books, including the collections Pedagogies of Public Memory: Teaching Writing and Rhetoric at Museums, Archives, and Memorials (Greer and Grobman 2016), In the Archives of Composition: Writing and Rhetoric in High Schools and Normal Schools (Ostergaard and Wood 2015), and the textbook Primary Research and Writing: People, Places, and Spaces (Gaillet and Eble 2016), reflect a focus on archival pedagogies in rhetoric and composition studies. This research demonstrates that teaching with archives facilitates active learning. In addition, teaching with archives provides an ideal opportunity to teach information literacy. And from a digital humanities perspective, archival material can be analyzed and repurposed in new ways for new audiences, as our projects demonstrate.

In previous articles, Hayden (2015; 2017) has enumerated the benefits of teaching with archives related to what Susan Wells (2009) calls the “gifts of the archives”: archival research teaches students 1) to resist simple answers to their research questions, 2) to contribute to ongoing conversations in a discipline through publishing undergraduate research, and 3) to connect with their research topics personally. In this essay, we focus on the third, to show what CUNY students learned by researching past CUNY students, and how encounters with archival materials can facilitate student-centered learning experiences in other institutions and contexts.

Composition and Rhetoric graduate students at the CUNY Graduate Center have produced several dissertations on the importance of CUNY to histories of the discipline (Molloy 2016; Savonick 2018). Anthony G. Picciano and Chet Jordan (2018) recently published CUNY’s First Fifty Years: Triumphs and Ordeals of a People’s University, which documents CUNY’s history in the context of free and open-admissions universities. The CUNY Digital History Archive not only aims to document the unique history of CUNY and its role in larger movements in higher education but also invites researchers, teachers, and students to collaborate on developing the archive and its uses for archival and digital humanities assignments in CUNY courses (Brier 2017). The CUNY Digital History Archive reflects both CUNY’s emphasis on archives and on publishing on digital platforms. All of these projects document CUNY’s history and the teachers and students who have shaped it. Students in our courses add to these histories while constructing a unique history of activist students and their roles in larger social movements. And it is important to us that undergraduate students rather than faculty do this work, both to highlight the value of archives and to involve undergraduate students in documenting institutional memory.

According to Ekaterina Haskins (2007), we need to go beyond memory work that is done by those in power. Haskins (2007, 402) notes, “relegating the task of remembering to official institutions and artifacts arguably weakens the need for a political community actively to remember its past.” When current CUNY students use archival research to narrate the memory of former CUNY students, they participate in a “continuous transmission of shared past through participatory performance” (Haskins 2007, 402).

Students in our courses performed research in the institutional archives at Hunter College and the Tamiment Library at New York University, exploring topics such as the efforts of Hunter women to establish free kindergarten in New York City, to organize the Lenox Hill Settlement House, and to become involved in CUNY student activism during the two World Wars and the Spanish Civil War. And in a “meta-analytic” topic, some students have researched and analyzed the research processes of past student researchers at Hunter, whose typewritten, whited-out drafts give insight into the revision processes of earlier generations of students. Whether they were collecting stories of women returning to college, documenting the involvement of students in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade during the Spanish Civil War, or processing archival collections, they were becoming both active agents of generational transmission and digital archivists themselves. These students not only recovered the voices of CUNY students, such as the “returning woman” and Abraham Lincoln volunteers, but they also extended the original goals of these past students in a new digital context, creating their own digital archives, either in written or multimedia form, blending the voices of the past and present students of CUNY.

Goals

Archives enable unique pedagogical approaches to the topics of our courses. María’s undergraduate courses concentrated on twentieth-century Spanish literature, where the Spanish Civil War (SCW) is a constant presence in class discussions, whether through the exiled poets of the 1927 generation, the novels of tremendismo, or the issues of memory and identity in today’s literary Spain. The SCW served as a common subject uniting historical and fictional narratives in the course. The Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives (ALBA), which include primary-source documents related to a group of Americans who volunteered to serve in the SCW, helped bring the past to life for contemporary CUNY students. The Lincoln Brigade, the American battalion that participated in the Spanish Civil War within the International Brigades, included about 2800 men and women who left the US between 1936 and 1938 to fight fascism in Spain. The Lincoln Brigade’s commitment was an act of disobedience to the US government, which remained neutral, while other Western nations signed a non-intervention pact when the Spanish Civil War began in 1936. Some of these volunteers were CUNY faculty and students themselves. In the Narrating Memory project, today’s students connected with the stories and experiences of American volunteers in the SCW and began to understand why fellow CUNY students left everything and sailed to Spain to fight a war the US government largely ignored.

Wendy’s undergraduate courses incorporated the Hunter College Archives to show the centrality of recovery of lost voices to the field of rhetoric. Researching activist students, teachers, and writers in a local context allowed students to enter scholarly conversations about historiography and institutional memory. The archive project introduced students to a new method of research and information literacy skills.

Initially, we both hoped assigning archival research would allow undergraduates to make their own historical discoveries, learn the skills of archival research, and reflect on the complexities of history as a subjective concept. The work that students produced in these courses exceeded our expectations.

The Archives

New York City provides teachers access to many physical archives, such as the Brooklyn Historical Society, the Lesbian Herstory Archives, and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, among others. We concentrate here on the pedagogical opportunities offered by institutional archives: the Hunter College Archives and the ALBA collection at the Tamiment Library at New York University.

The Hunter College Archives include collections dating back to Hunter’s founding in 1870 as the Normal School. Student projects have focused on Hunter College student communities, such as the newsletters Returning Woman (1981–1998) and Lesbians Rising (1976–1983); on writers and teachers at Hunter College, such as Kate Simon (1959–1989) and Helen Gray Cone (1859–1934); and on Hunter students’ roles in larger movements, such as the Women’s City Club (1915–2011) and the Lenox Hill Settlement House (1892–2015). In addition to researching existing materials in the archives, they added to the archives with documents from their own clubs, worked with unprocessed collections, and created a finding aid, all to tell the story of the students of CUNY and their roles in larger social movements.

The Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives at the Tamiment Library contain materials related to American involvement in the Spanish Civil War. The Tamiment Library is a nationally-recognized space for scholars interested in researching labor history, civil rights movements, and left political ideology. The collection holds about 50,000 books, 15,000 periodicals, and about one million pamphlets and ephemera. The Tamiment Library contains letters, books, photographs, news, interviews, and other compelling information that is imperative to understand the contribution of the Lincolns.

Librarian Collaboration

At the Tamiment, María initially worked with former Public Services and Instruction Librarian Kate Donovan and currently works with Public Service Librarian Sara Moazeni, and Reference Associate Danielle Nista. The librarians reviewed the course syllabus and became familiar with the course goals prior to the first class visit. After introducing the students to the ALBA collection, the librarians provided an information sheet and instructional activities for students to discuss in groups in order to familiarize them with the archival material. In February 2018, librarian Danielle Nista arranged four sets of documents (posters, diaries, and photos) for our analysis. She organized four groups of approximately five students so they could rotate and discuss each item to provide a broad introduction to the archives.

At the Hunter College Archives, former head archivists Julio Hernandez-Delgado and Louise Sherby developed an introductory session where students read several articles on Hunter College history before their visit. During the class visit, the archivists led a discussion of the assigned articles, introduced the collections, and demonstrated how to use a finding aid. More than a “how to” session, the introduction was a discussion of the history of the college as documented in the archives. Students used that discussion to formulate research questions. Iris developed a library guide to the archives that includes general information about the types of materials held in archives, instructions on citing archival material, and links to online exhibitions.

As the project developed, Iris joined Wendy’s classes as an embedded librarian, and in that role integrated a digital humanities focus. Beyond the embedded librarian’s traditional responsibilities such as helping students with research and navigating physical and digital archives, for these archival assignments Iris guided students in using WordPress to communicate their work to a broader audience, thereby acting as knowledge producers. Iris introduced students to digital tools such as the timeline software Tiki Toki and Weebly, a content management system more user friendly than WordPress. She commented on students’ blog posts to point out information gaps and suggested resources to help fill those gaps. From her position within the classroom, Iris established relationships with students and met with them both in groups and individually during class time. Through this process she was able to determine the best fit for individual projects based on each student’s comfort level with new technologies and features of tools. Overall, collaboration among embedded librarians, archivists, students, and faculty was integral to the success of student projects and to the class.

The Assignments

The class visit to the Tamiment helped students to understand the role of the archive in their final project, and from then on they visited the archive on their own. Each student chose one Lincoln volunteer as the subject of their final essay and researched archival material to elaborate their motives to fight in the war. The final paper, posted individually on the Narrating Memory website, represented the culmination of the semester-long research they undertook at the Tamiment.

Students in the rhetoric courses were assigned to find a document or documents in the Hunter archives and tell that document’s story in relation to any theme in the course, such as women’s activism, silencing, writing, education, or civil rights rhetoric. They documented their findings and their research process on the Rhetorical Reflections blog (named by the students). They often detailed how they went into the archives interested in one topic and had to abandon that topic because it lacked material or because they found a more interesting topic. Wendy emphasized in class that they should document their entire process, even when it did not lead to anything. As Lynee Gaillet (2017, 109) points out, “Primary investigation often involves following a fun trail of clues … or a serendipitous find. Unfortunately, however, academicians often manage to stifle this most interesting aspect of our research in publications and rarely explain the process we find so engaging to either readers or students.” Based on these ideas, we asked students to include as many details as possible on their process, even when they found documents not relevant to their research topic, so future students can learn from their process and better locate materials relevant to their own projects. The class focus on process led to a publication in Young Scholars in Writing by student Esra Padgett (2015), whose article “Feminist Research as Journey (Or, Like, Whatever?)” asserts, “Rather than pinning down an answer, [this] essay attempts to follow the trajectory of the research itself, observing how perspectives can shift drastically depending on one’s method of inquiry.”

The digital aspects of our assignments aligned with digital humanities objectives of learning to locate, present, support, and cite research and scholarship. Through these assignments, students engaged with technology and considered different modes of presentation to support their scholarship. In addition to learning new ways to engage with content and enhance their digital literacy, students developed visual awareness through the process of finding appropriate images and media to complement textual content, and sometimes to represent content without text.

Both projects foreground the role of active learning. While we could teach students about the Spanish Civil War or rhetorical traditions using other methods such as assigning anthologies of primary or secondary sources, these methods would not engage students the same way. The true motivation to learn about the course material begins in the archives. From the moment students came into contact with the documents on the ALB volunteers at the Tamiment, everything they studied became meaningful. For example, we found that student writing improves through the projects, whether because of their passion for the topic or the blog format. Students also recognized the relevance of their writing style and accuracy, as their work was accessed by outside readers, some of whom have a connection with the material. All of the students began to understand how their voices were contributing to efforts to interrogate public memory. Writing, here, became a direct form of activism, as well as an academic exercise.

CUNY Connections

The archival visits generated a variety of connections for students and by students. Students connected with the stories and experiences of American volunteers in the SCW and began to understand why fellow CUNY students left everything and sailed to Spain to fight a war the US government largely ignored. Student Ashley Martinez found that the archive lacked information about David McKelvy White, a professor of English at Brooklyn College who unexpectedly left his teaching position in 1937 to fight in the SCW, so she expanded her search well beyond the Tamiment: “I have embarked on a nationwide search for information. I have found letters and stories [McKelvy White] wrote at the NYPL, additional documents from the Ohio Historical Society, which sent me the letters between David and his father, the Governor of Ohio, as well as documents he wrote during his political activism years after the SCW.” While Ashley began her project from an impartial position, keeping McKelvy White’s memory alive turned into an urgent task, a need to memorialize his life. Like many of the fictional characters discussed in the course, such as Lola and Javier Cercas in Soldiers of Salamis (Cercas 2001), Carlos Sousa in The Carpenter’s Pencil (Rivas 1998), or Minaya in Beatus Ille (Muñoz Molina 1986), Ashley became a young receptor of history, an interlocutor to an older generation keeping the memories of those who fought in the SCW alive.

Several students chose to research someone with a connection to their own life and academic interests. For instance, student Cody Butler wanted to study the life of Fernando Gerassi, the father of his professor at Queens College, John “Tito” Gerassi. Leon Ramotar wanted to learn about Hunter College alumna Helene Weissman, who joined the ALB as a medical administrative aid and interpreter. Pre-med student Kathleen Jedruszczuk wrote her final essay on the renowned Dr. Edward K. Barsky, a surgeon, political activist, and graduate from City College. In her project, Kathleen explained, “Reading about Edward Barsky’s life made me realize that he was more than just ‘aid to Spain’; he was an aid to humanity. Anyone who risks their life for people, goes to jail for the people, and becomes a doctor to help those people is an aid to humanity.” Student Rebecca Halff focused on Robert Klonsky and the relevance of Brownsville, Brooklyn, a diverse, working-class, and Jewish community with strong communist leanings, as a catalyst to join the ALB.

Through their research, students placed themselves into the stories told in the archives, both implicitly and explicitly. For example, Elyse Orecchio and Janice Johnson, both non–traditional-aged “returning women,” researched the archives of the Returning Woman newsletter at Hunter and reflected on the connections they found. Janice perused the collection until she found work by a Puerto Rican woman like herself who was returning to college. Janice stated, “I was able to look and reflect on my own experience as a returning woman. I am that woman in the newsletter. I am the returning woman, the returning Hispanic woman, the returning student.” Elyse related, “I didn’t expect to get emotional when I looked through the first few issues of the newsletter. There was a lot of supportive, motivational writing that acknowledged this idea that you have a million other things going on, but you are doing this great thing for yourself.” Janice decided to create her own website that showcased her primary archival documents and video interviews with classmates—including Elyse—on the struggles of women returning to college.

The online format of the projects allowed students to write for audiences beyond the classroom and enabled explicit connections with those audiences. For example, student Haley Trunkett wrote her essay on May Levine Hartzman, a New Yorker who worked as an operating nurse during the SCW. She met her husband, Jacob Hartzman, in Spain, where he was an ambulance driver. Their son Peter provided information to Haley. Student Laura Montoya received feedback from Georgia Wever, the coordinator of the Friends and Family of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives. Laura wrote about Jewish involvement in the SCW, and in particular, the story of volunteer Mark Strauss. In her comment, Georgia Wever wrote:

Dear Laura, What an interesting and inspiring story of a great person. With very little information, you manage to capture his humor and courage. I am disappointed that I never met him. I attended many reunions and banquets of the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade at which all the veterans would stand, but I don’t recall him. I regret that you did not locate anyone who knew him because I would like to know more about his life after Spain. Perhaps someone will read this essay on our listserv and leave a reply. Thank you again for the affection you put into his story.

Students also wrote to former students and their families. For example, Carl Creighton wrote to the family of the president of the Hunter College Suffrage Clubs, who knew nothing of her suffrage activities. Elyse emailed the Hunter student who wrote the paper she found in the archives and received a response that connected the past and the present. As Deborah Mutnick (2016) explains, “Part of the archive’s appeal to my students is what Lucy Lippard refers to as the ‘lure of the local.’ Students encounter documents that reveal the history of the very streets they walk, and they gain a sense of empathy for the historical actors they study.” For our students, the people whose stories are told in the archives were more than only “historical actors,” but real people they interacted with through digital connections.

Melissa Hutton’s project in Wendy’s fall 2015 class prompted us to think of the blogs themselves as an archive. She responded to scholarship on digital writing by analyzing the writing and research practices of her peers as documented on their blogs. She concluded, “These blog posts are a perfect example of primary documents being born digitally and facilitating a place for online research.” Melissa’s work inspired revisions to the archive assignment. For example, Wendy added a requirement to link to other student blog posts on similar topics and tag the blogs with descriptors such as “World War II” for blogs discussing women’s activism during the war, thus turning the website into a student-written and -researched history of a tradition at Hunter. In fall 2018, Wendy is approaching the archive assignment differently by having her first-year writing students read student blogs first, and then work with the same documents previous students did and develop new questions about those documents and compare different archival research processes. The blogging technology thus creates an archive of students’ research in archives, useful to future students researching in archives.

Conclusion

In the digital world, research can seem a disembodied and impersonal task for undergraduate students. We found that the physicality of archival research, far from being a burden to students, is the very thing that makes them connect with their research and their institution. Inviting a librarian into the classroom personalizes research and encourages students’ confidence in their work as they receive support to facilitate their research and present it in an appropriate format.

From a librarian’s perspective, the lessons students learn from archival research, particularly understanding the differences between primary and secondary sources and how one can provide support for the other, make them stronger researchers even when they are not researching in archives. Melissa and Iris discussed how this distinction between primary and secondary sources needs to be redefined in a digital context. For example, a student blog post may not be an authoritative source to cite, but Melissa noted the value of these blog posts to researchers in the field of library studies or composition studies: “While regarding student blog posts as secondary sources might not be wholly credible for authenticating an academic paper or constructing a historical narrative, viewing them as primary sources gives them new meaning as legitimate firsthand student accounts. … Student blog posts acquire a currency hard to find in finely-combed scholarly sources. In this case, student blog posts provide us with interpretations of rhetoric and archival research instruction.” They might be used as an archive to explore student research processes from an academic perspective or as a mode of communication between scholars. If someone were doing research on the ALB or on the struggles of women returning to college, the blogs on Narrating Memory or Rhetorical Reflections may be a useful window into those topics.

Researching CUNY students and professors through the ALBA collection and the institutional archives at Hunter placed students within a tradition of student activists as they contributed to the process of memorialization. The act of telling the story of someone unknown and becoming an intermediary of both primary and secondary internet research also meant their work was meaningful in ways that traditional research papers may not be (Keegan and McElroy 2015; Mutnick 2016). Students in our courses became active agents of generational transmission for the ALB volunteers and the history of CUNY by transmitting their life histories and shared experiences.

Our students directly benefited from the collaboration between their instructor and librarians, as well as Hunter College and the Tamiment’s commitment to making their collections available. The accessibility of archives to students, researchers, and the general reader can make them a democratic and pedagogical tool. Unfortunately, many archives are suffering from serious funding cuts and increasingly limited access. The future of archives depends on valuing historical materials and reimagining their purposes in the present. Eighty years after the SCW began, we continue to learn about the crucial role that the ALB volunteers played in the fight against fascism. Delmer Berg, the last Lincoln alive, died on February 28th, 2016. Thanks to the younger American generations who narrate their legacy, voices like Berg’s and those of former CUNY students will remain in history, and in our memory.