Teaching Communication Skills to Medical Students in a Virtual World

Susan Lowes, Teachers College/Columbia University

Gillian Hamilton, University of Arizona College of Medicine and Hospice of the Valley

Vicki Hochstetler, Hospice of the Valley

SeungOh Paek, University of Hawaii at Manoa

Abstract

The ability to communicate is a core competency for medical practitioners and role-playing is an increasingly common tool for teaching communication skills in medical schools around the world. While there is general agreement that the outcomes are better when these skills are practiced, not just preached (Lane and Rollnick 2007; Rosenbaum, Ferguson, and Lobas 2004; Andrade et al. 2010; Cahan et al. 2010; Orgel, McCarter, and Jacob 2010), in-person role-plays are time consuming and resource intensive. As a result, in recent years a number of medical schools have experimented with using virtual environments as sites for role-plays (for examples see Lane and Rollnick 2007; Hulsman, Harmsen, and Fabriek 2009; Andrade et al., 2010; Mantovani et al. 2003; Alverson et al. 2005). A recent meta-analysis of controlled studies using virtual patients found that in general there was a positive effect, although the type and extent of the effect depended on the outcomes being considered (Consorti et al. 2012). Only four of the studies examined addressed communication skills, and the findings were less clear in this area.

This article describes a design-based research intervention that used virtual role-plays, conducted in Second Life, to train medical students to communicate with patients and family members about end-of-life care decisions. The intervention was designed at Hospice of the Valley (HOV), the largest free-standing hospice in the country, located in Phoenix, Arizona, while the research was conducted by the Institute for Learning Technologies at Teachers College, Columbia University. The goal of design-based research projects is to use each iteration to inform the next, a process that has been characterized as “research through mistakes” (Anderson and Shattuck 2012). Thus, the program was adjusted over the course of eight months, evolving from role-plays in face-to-face sessions to role-plays conducted in Second Life, from role-plays with two HOV staff members playing the roles of mentor and patient to role-plays with one staff member playing both roles, and from role-plays taking place in an off-the-shelf Second Life-room to role-plays taking place in a more hospice-like virtual setting. The hope was that the anonymity of the virtual environment, with students and mentors communicating through avatars, would reduce the anxiety that students reported with face-to-face role-plays, allowing them to focus on their interactions with the virtual patients.

In this article, we first look at the evolution of the project and then analyze the data that was collected at each stage.

Background

In 2006, Hospice of the Valley (HOV) received funding from the Virginia G. Piper Charitable Trust to develop a short program in its facilities to provide residents and hospitalists in the Phoenix area with an introduction to the principles of good palliative care. The program was tailored to the resident/hospitalist specialty and included a half-day group orientation focusing on hospice services, pain management, and advance directives, followed by a series of half-day visits: to an in-patient unit with the unit’s medical director; to a patient’s home with a nurse, social worker, or chaplain; and to a dementia unit. The orientation session included role-plays, using three scenarios common in palliative care: two involve discussing end-of-life decisions with patients and the third involves talking with a patient’s family. For each scenario, a resident or hospitalist would play the role of doctor, an actor would play the role of patient, and the doctor who was facilitating the session would interrupt to point to mistakes as they happened, while the rest of the group watched. The goal was to provide a toolkit of techniques that practitioners could use in different situations.

The program received very high ratings from the 150 residents and hospitalists who took part and in late 2008 the University of Arizona College of Medicine asked HOV to develop a similar program for third-year medical students. This program, which began in January 2009, replicated the hospitalist/resident program with four half-day sessions spread over three months, but without the role-plays in the orientation. Then, in December 2010, the orientation was expanded to include the role-plays, using the same scenarios that had been used with the residents and hospitalists, again in a group setting.

The medical students proved a far more challenging group, however: in their post-program evaluations, they wanted more “hard science” and expressed a dislike of instruction on “soft” skills. As for the role-plays, not only did these students do poorly, but in their evaluations they indicated that they disliked them, did not think them effective, and in general would have preferred that they never happen. This is a not uncommon reaction to in-person role-plays (for discussions of in-person role-plays, see Lane and Rollnick 2007; Rosenbaum, Ferguson, and Lobas 2004; Arnold and Koczwara 2006).

The main reason the medical students disliked the role-plays was that they felt uncomfortable: uncomfortable acting in public and uncomfortable having their weaknesses pointed out in front of their peers. Here are three sample comments from their evaluations:

- “The improv sessions were my least favorite of all the activities. They are stressful and embarrassing for those of us called upon to go up to the front of the classroom and act out scenarios with fake patients and they really are not very helpful at all.”

- “I do not like ‘interactive’ learning where people are put on the spot. I think it’s enough to have case-based lectures.”

- “Having to sit through the ‘interviews’ in lecture. They were not helpful or productive and students were more worried about being chosen to speak than interested in the material… I think the hospice experience would have been MUCH better without having to speak involuntarily on the microphone when a lecture would have been more productive.”

The students were also unhappy because these were group sessions and not everyone was equally involved. Here are three responses from students who listed the role-plays as the worst or most difficult experiences of the entire program:

- “I don’t think the role-playing as an entire class is very good. It doesn’t engage everybody and would be more appropriate for a doctoring session.”

- “The skits in the large group. Large groups work well for lectures. It is not effective to have discussions in large group settings. People lose interest and it is not beneficial to try to force them to pay attention.”

- “I really don’t care for the ‘acting out’ ‘fake patient’ scenarios in the lecture. The ‘pretending’ is hard to stomach as a grown adult, it seems more like an opportunity for people to display their class clown abilities, as opposed to learning appropriate approaches to hospice care.”

It was also not clear that the students felt that the experience had prepared them well for the two key aspects of communication—discussing end-of-life decisions with patients and talking with patients about death and dying—with 20 percent or less reporting in the evaluation that they felt the HOV experience had prepared them “very well” to do either of these and between 25 percent and 30 percent saying they did not feel they had prepared them well at all:

Table 1

How well do you feel the HOV experience prepared you for:

Discussing end of life decisions with patients

(n=68)

| Very well |

21% |

| Moderately well |

54% |

| Not very well |

13% |

| Not well at all |

12% |

Talking with a patient about death and dying

(n=68)

| Very well |

18% |

| Moderately well |

51% |

| Not very well |

22% |

| Not well at all |

9% |

As a result of the large number of negative evaluations, in July 2011 the program was modified to move the role-plays into Second Life, where a student’s avatar would interact with the avatar of a patient or family member (depending on the scenario) in a simulated patient’s room in a hospice palliative care unit, with the student sitting at a computer in one HOV office and the facilitator in another. It was hoped that the novelty of a virtual environment would not only be attractive to the students, but that it would have a number of affordances. It would remove the anxiety of the in-person role-plays, the distraction of an audience, and the added burden of having to fully act out a part, not only verbally but also physically, with appropriate body language and facial expressions. In addition, the setting would be a (simulated) hospice room rather than a conference room that was totally disconnected from the situation in the role-play. Thus, although the Second Life role-plays would be less directly embodied than face-to-face role-plays, the sense of place (the simulated in-patient unit) was potentially greater and the use of avatars made for surrogate or partial embodiment (Black et al. 2012). Perhaps equally important, the students would not be watching other members of a group and occasionally participating but would be doing this work on their own (thus allowing them more focused time with each scenario) and would be somewhat anonymous to the facilitators.

However, it was also recognized that there were potential pitfalls. First, experiments with Second Life at Teachers College had found that there were technical challenges with avatar movement and with the audio, as well as a steep learning curve for new users. Because of logistics and time constraints, it was not possible to train the students in navigating within the environment, so interactions would have to focus on voice rather than movement. Second, Barney Dalgarno and Mark Lee, after a detailed review of the research on the potential benefits of 3-D virtual environments such as Second Life, proposed that for these environments to provide successful learning experiences, they must have both representational fidelity and learner interaction (Dalgarno and Lee 2010, 15). In particular, the user must be able to construct an identity, create a sense of presence by interacting with the environment, and create a sense of co-presence by interacting with others in that environment. The first two would be missing and the third would be limited. It therefore seemed possible that the students would not experience the degree of “psychological immersion” that Dalgarno and Lee believed to be necessary engagement and learning (Dalgarno and Lee 2010, 14). It was also possible that the one-on-one coaching approach might not be as effective as the group discussion that had taken place during the in-person group role-plays (for a discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of individual and group role-plays, see Rosenbaum, Ferguson, and Lobas 2004)—although given the students’ comments on the group experience, this seemed unlikely.

Although the total number of hours HOV staff spent with students would increase compared to the group in-person role-plays, it was hoped that the individual role-plays would be more efficient and easier for all those involved because they could be scheduled back-to-back on the same day. In addition, the logistics would be more easily managed because mentors and students did not have to be in the same building.

In the first round (July), there were three avatars in Second Life: one each for the patient/family member, the student, and a practitioner-mentor who made comments and suggestions. Having three participants proved difficult to manage logistically as well as demanding in terms of personnel time, so beginning in August, mentors acted as patients/family members and also gave feedback to the student throughout the role-play. Although we were concerned that having the roles of patient and mentor played by the same person would be disconcerting to the students, allowing the students to focus on their avatars seemed to make interruptions less intrusive. Recordings of sessions show the students simply stopping, discussing the moment with the mentor, and then going back into the role. Students might stop and say, “I don’t know what to say next!” or “Oh, help! I’m stuck! I went down the wrong path!” The combined roles unexpectedly allowed the mentor to guide the scenario as it unfolded, stopping the student, pointing out what was wrong, and proposing a different approach.

These two video clips give a glimpse of this process at work. In the first clip, medical student Josh is talking to a patient. In the second clip, medical student Maggie is talking to a patient’s caregiver. Both are very common scenarios in end of care settings.

Josh

Maggie

We were concerned that Second Life would act as a barrier rather than a facilitator, since research has shown that facility with computer use is a significant determinant of perceived usefulness and ease of use among healthcare professionals (Chow et al. 2012). Although this seemed unlikely to be an issue with the younger and more technically adept medical students, it could have been a problem with HOV staff. Further, in terms of technology, there was also concern as to whether Second Life would prove viable as a virtual environment. In fact, in the first few months it was full of glitches—the audio was unpredictable, screens froze, and sometimes users got kicked out of the system. When this happened, the image of the Second Life room remained on the screen but mentors and students moved the audio to the telephone. Audio problems were resolved by using Skype for all the audio. In addition, the students complained that the room in Second Life (a stock room) was distracting because it was so unrealistic (see Chen et al. 2011 for an interesting discussion of the relationship between feelings of presence and levels of abstraction in a virtual environment). HOV therefore decided to build its own campus in Second Life, which involved hiring an outside designer. The HOV palliative care unit is in a converted house and the contractor was sent pictures of the unit, including the common living room and a patient room, so that the overall feeling is as much as possible similar to the unit the medical students had visited in person. This production work took some time and was not completed until October.

Research Design

Our research into the use of Second Life at Hospice of the Valley had begun in Spring 2011 with a small project (jointly funded by the Mayo Clinic and HOV) led by Lisa Thompson, a Fellow in Hospice and Palliative Care. A mix of fifteen students and residents were given a scenario and then assigned to one of three pathways: an in-person didactic session (a PowerPoint presentation followed by a discussion with a doctor/mentor); an interactive session in Second Life with an actor playing the role of simulated patient and a doctor/mentor giving in-person advice as the scenario evolved; and no training. This was followed by a repeat of the scenario, live, with an actor playing the patient. A doctor and two experienced nurses acted as an expert panel and ranked each student’s performance in eight key communication skills before and after the intervention. The results showed that although all the students improved, those who used Second Life improved the most overall, and in all areas being assessed (Thompson and Prommer 2012). As a result, in July 2011 all HOV role-plays were moved into Second Life.

The research discussed below addresses the following questions:

- Did the students feel they learned the basic principles of communicating with patients or their family members better when doing the role-plays in Second Life than they had when they had done them in-person?

- Were the students more satisfied with the role-plays done in Second Life than they were with the role-plays done in-person?

- Did the students learn the basic principles of communicating with patients and family members when they did the role-plays in Second Life?

- Can using Second Life be an efficient and cost-effective way to teach this type of communication?

Procedure

Students came to the HOV office, were given a few minutes to read over a printed version of a scenario, and then played it out over the next fifteen or twenty minutes. There were three scenarios that dealt with three very common end-of-life care situations: obtaining code status; the placement of a feeding tube in an Alzheimer’s patient (a discussion with the patient’s wife); and a discussion of whether to admit a patient to hospice. The facilitators/mentors evaluated the students’ performances in each scenario using a simple rubric based on three basic principles of communication for physicians:

- Did the trainee begin by finding out what the patient/family knew?

- Did the trainee listen at least 50 percent of the time?

- Did the trainee explain in understandable language with no medical jargon?

Students were also evaluated on the specific content or questions required in each scenario (for example, whether advance directives had ever been discussed, what happens when feedings tubes are used with advanced Alzheimer’s patients, etc.).

Each item was rated from 1 to 3. The highest possible score for each scenario was 12, and the highest total score was 36. The scoring was done immediately following each scenario, but the results were not revealed to the student.

In addition to the mentors’ evaluations, the students completed a post-program evaluation that asked about the entire HOV experience and included a specific question about Second Life.

Data Sets

Because the experience in July 2011 was substantially different from the subsequent role-plays (when the mentor also played the role of patient), the July data were dropped from the analysis and only the August 2011 – February 2012 data were considered. Forty-two students participated: 23 did all the scenarios in Second Life, 13 did a mix of Second Life and telephone (because Second Life broke down during the course of the first or second scenario), and 6 did scenarios only on the telephone (because Second Life would not work at all). All 42 students were scored, while the online survey that was given to the students at the end of the program was completed by 41 of the 42 participants.

Results

In response to an open-ended question that asked whether they had liked or not liked the virtual role-play experience and what they had liked/not liked about it, 83 percent of the 36 students who responded to the question said they had liked it. A higher percentage of those who had used Second Life had liked it (76 percent) compared to of those who used a Second Life/phone combination or phone alone (69 percent). There were some who were positive about the experience but had reservations, but only six students were entirely negative. All six said they would prefer role-plays that were one-on-one and in person.

The students who liked the virtual role-plays, in any mode, liked them for two main reasons: they felt they were immediately applicable and they appreciated immediate feedback.

Students who thought the role-playing experience was immediately applicable offered the following types of comments:

- “The role-playing session was the most readily applicable to our everyday duties.”

- “I really enjoyed the clinical interviewing because it felt it started to build a foundation of skills I will need as I move forward in my career.”

- “I liked the clinical interviewing best. The activity was quick, succinct, to the point, and best prepared me for conversations I may have to have as a physician in the future.”

Those who liked getting immediate feedback offered these types of comments:

- “The interviewing seemed as real as it could get and the insight was helpful when I got caught up at an awkward moment where I wasn’t sure where to go.”

- “Second Life allowed me to practice talking with a patient about tough decisions and ways to say things that convey a message and are gentle to the patient.”

- “It was interactive and I got feedback immediately. It is also something we can apply to many different clinical situations.”

Those who had reservations liked having the interview training but were not enamored with Second Life:

- “Practicing these skills was useful and I’m glad this is a part of the rotation. However, I don’t feel the computer program aided the experience.”

- “While I thought the experience was good, it would be much better to have a real person sitting in front of you with eye contact, expressions, and without the delay in speaking-to-hearing.”

The hypothesis that building in distance by having the student and mentor communicate through Second Life would reduce anxiety while doing the role-plays one-on-one would allow the students to focus on the scenario seemed to be true for a large majority of the students. There were many comments such as the following:

- “I really like the Second Life and telephone to teach clinical interviewing rather than in-person role-plays because it allows you to relax a little more and work through the conversation. I like that you can still get feedback and commentary as you go, but it is a much more relaxed and I think productive environment.”

- “I found it to be a much more comfortable learning environment given I was in the room by myself without any pressure. Probably the best way to learn something so personal and important.”

- “I liked that it doesn’t provoke as much anxiety as live role-playing and I was able to learn a great deal.”

- “I liked seeing the illustration of a face-to-face encounter, as it made me feel that I was really in this situation but without the added anxiety of a ‘real’ person in front of me…. I also liked the role-playing situation, but liked being able to ‘break character’ if necessary to ask questions and get help immediately, rather than waiting until the end of the encounter for advice and feedback.”

Student Self-Assessment of Preparation

The post-program evaluation repeated one of the questions asked on the prior evaluation about whether the students felt they were better prepared to discuss end-of-life decisions with patients as a result of the HOV experience.1 The difference between the ratings for those who had done the role-plays in person and those who had done them virtually was striking:

Table 2

Percent reporting that they felt “very well” prepared to discuss end-of-life care decisions

with a patient as a result of the HOV experience

|

In-person (n=68) |

Virtual (n=41) |

|

| Very well |

21% |

54% |

| Moderately well |

54% |

44% |

| Not very well |

13% |

2% |

| Not well at all |

12% |

0% |

|

100% |

100% |

We next looked to see if there was a difference in the students’ evaluation of their own learning among the three modes. We focused on those who said that the program has prepared them “very well” (the highest choice) to “discuss end-of-life-care decisions with a patient” and to “discuss difficult subjects with patients.”

If we look at the results for the entire August 2011-February 2012 period, we see that those who used a mix of Second Life and phone felt that they learned more than those who used Second Life alone, with those who used only the phone reporting that they learned the least:

Table 3

Percent reporting that they felt “very well” prepared to do the following

|

Second Life |

Mixed (n=13) |

Phone (n=6) |

|

| Discuss end-of-life care decisions with a patient |

45% |

85% |

17% |

| Discuss difficult subjects with patients |

64% |

69% |

33% |

Since the audio problems were entirely in the August-November period, when almost 60 percent of the participants had to go over from Second Life to the telephone or used only the phone (none did so in the December-February period) and since the Second Life room was not a realistic representation of the hospice room until November, it seemed possible that the scores for Second Life alone might differ for the two time periods. The number of participants is small, but when we compare the students’ evaluations of their own learning in Second Life, we see that there were indeed differences:

Table 4

Percent reporting that the program prepared them “very well” to do the following

Students who used only Second Life

|

August-November (n=9) |

December-February |

|

| Discuss end-of-life care decisions with a patient |

22% |

62% |

| Discuss difficult subjects with patients |

56% |

69% |

Perhaps the most surprising result—at least to the HOV staff—was that the clinical interviewing experience was the second highest rated item (after a visit to a palliative care unit with a doctor) in the ratings of all the program activities, with 60 percent saying they had gained “a great deal” (the highest rating) from the experience. In this case also, the ratings from those who used only Second Life were lower overall than the ratings from the group that used both, but were much higher for the second period compared to the first:

Table 5

Percent reporting that they gained “a great deal” from the clinical interviewing experience

All students, all time periods

|

Second Life |

Mixed (n=13) |

Phone (n=6) |

|

50% |

77% |

50% |

Table 6

Percent reporting that they gained “a great deal” from the clinical interviewing experience

Second Life only

|

August-November (n=9) |

December-February |

|

33% |

62% |

In addition, 8 of the 41 students listed the virtual role-play as the best experience they had had in the entire program, a striking difference from the in-person students, many of whom had considered it the worst experience of the program.

But Did They Learn?

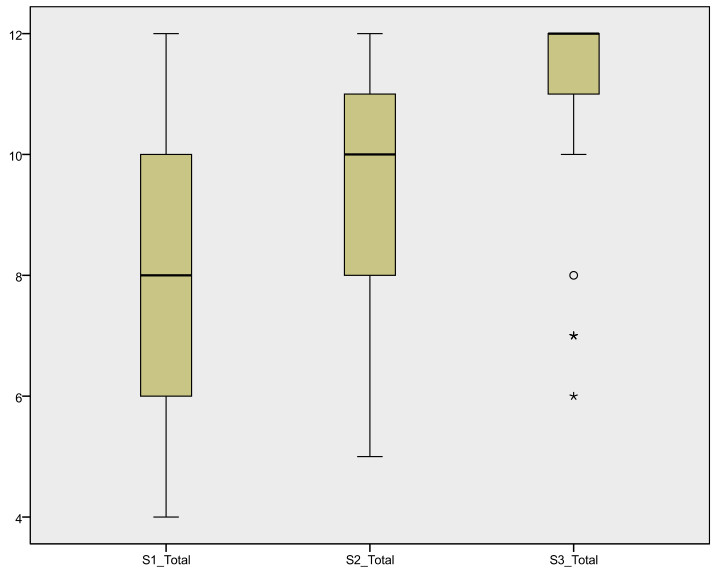

Student satisfaction was important, but only if the students also showed evidence of learning. The chart below not only shows the improvement from scenario to scenario (S1 to S2 to S3) but that the range scores narrowed (i.e., the boxes became smaller and the line inside the box that represents the mean score for each scenario increased). A majority (67%) had perfect scores of 12 on the third scenario:

Unlike the students’ self-assessments of learning, with the formal assessments there was no statistically significant difference in the combined mean scores for all three scenarios whether the student did the scenarios on the phone, in Second Life, or in a mixed mode (p > .05):

Table 7

Mean scores for all scenarios combined

|

N |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

|

| Phone |

6 |

30.6667 |

2.06559 |

| Second Life |

23 |

28.3913 |

3.82265 |

| Mixed |

13 |

28.3077 |

5.85071 |

| Total |

42 |

28.6905 |

4.36442 |

There was also no significant difference between the modalities when the scores on the first scenario were controlled for (p > .05).

And even if we look only at those who used Second Life and compare the August-November and December-February groups, we find no significant difference in the mean scores between the two time periods (p > .05):

Table 8

Mean scenario scores, Second Life only, by time period

|

N |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

|

| August-November |

10 |

29.0000 |

4.71405 |

| December-February |

13 |

27.9231 |

3.09466 |

However, although there were no significant differences in the mean scores between the three modes, there were differences in how much students in each mode gained from Scenario 1 to Scenario 2 and from Scenario 2 to Scenario 3 (hereafter S1, S2, S3). (Those who did the scenarios entirely on the phone are dropped from the analysis here, since there were only six, three in the first time period and three in the second.) The overall mean gain was greater for the Second Life group than for the Mixed group:

Table 9

Mean gain from scenario to scenario, by group

|

S1 to S2 |

S2 to S3 |

Total gain |

|

| All |

1.42 |

1.78 |

3.19 |

| Second Life |

1.39 |

2.13 |

3.52 |

| Mixed |

1.46 |

1.15 |

2.62 |

The gains from S1 to S2 and from S2 to S3 were statistically significant for those who used Second Life alone (p < .01), but only the gain from S1 to S2 was significant for the Mixed group (p < .05). In addition, the gain from S2 to S3 was considerably greater in the later time period, with the result that the overall gain for this later group was much greater than the overall gain for the Mixed group (which only existed in the earlier time period):

Table 10

Mean gain from scenario to scenario, by group and time period

|

S1 to S2 |

S2 to S3 |

Total gain |

|

| Second Life August-November |

1.00 |

1.80 |

2.80 |

| Second Life December-February |

1.69 |

2.38 |

4.08 |

| Mixed August-November |

1.46 |

1.15 |

2.62 |

Together, these results suggest that once the technical difficulties were resolved, Second Life was the more effective mode. It also suggests that at least three scenarios are needed if the role-plays are to be effective in this mode.

We were also interested in seeing if the students had difficulty with one particular item in the scoring rubric. The differences in the scores among items were not statistically significant, but they suggested that the students had the most difficulty listening and the least difficulty not using medical jargon. There was no difference between those who did the role-plays in Second Life compared to those who used the phone or mixed. The highest score for each scenario is 3:

Table 11

Mean scores by item, all students

| Began by finding out what the patient/family knew |

2.32 |

| Listened at least 50 percent of the time |

2.29 |

| Used understandable language with no medical jargon |

2.50 |

| Overall for specific content |

2.46 |

Efficiency and Cost Effectiveness

The final research question was whether using Second Life could be an efficient and cost-effective approach to teaching communication skills. Although HOV did not keep detailed cost and time estimates, it is clear that using Second Life was more demanding of staff time than the original iterations, when all the students met together for an orientation session that integrated the role-play. The face-to-face role-plays took about one hour out of a three-hour session and required an actor to play the role of patient and a practitioner to be the mentor. Once the role-plays moved to a virtual environment and the role of mentor and patient were combined, there was no need for an actor. Since each student now spent about an hour doing the role-plays, the student time was approximately the same but the mentor time increased by the number of students enrolled.

While at first the mentor/patient role was played by a doctor, in the final two months covered in this study, two nurses played this role. This reduced the cost in terms of salaried time, but not in terms of person-hours. Although the nurses reported that they were enjoying the process and the medical students appeared as receptive to the nurses as they were to the physician mentors—if indeed they knew the difference, since they did not see them in person—there was a possibility that this would not be sustainable, even though the mentors could complete their work from home or from another site, and could eat or drink during the process. On the other hand, as staff became more familiar with Second Life and the audio problems were resolved, the amount of technical support needed decreased dramatically. The net result has been that HOV decided the virtual role-plays in Second Life are so much more effective than the in-person version that the added expense is worthwhile.

Conclusion and Next Steps

With design-based research projects that evolve as rapidly as this one, the goal is not to come up with definitive results but to use the findings to inform the next iteration of the implementation. The results presented here show that the effectiveness of the Second Life role-plays increased over time, both in term of the students’ assessment of their own learning and from the point of view of their improved ability to demonstrate best practices from scenario to scenario. The HOV staff much prefers the use of Second Life to the in-person role-plays, with the expense of time compensated for by the flexibility of being able to work from their own desks when playing out the scenarios in the virtual environment. One of the next steps has been to train additional mentors in order to reduce the burden on what was originally a small group. However, this decision raised the issue of inter-rater reliability in the scenario scoring—with more mentors, it became important that all were scoring according to the same standards. HOV addressed this through a series of formal mentor training sessions, conducted by an outside facilitator. These sessions have had the unintended consequence of being very effective and very popular staff development exercises. In addition, the mobility of the patient/mentors in the Second Life environment has been improved so that they are less static and able to act, and react, more realistically. The goal has been to enhance the interaction between avatars and thereby further deepen the psychological immersion necessary for engagement and learning, as well to make the Second Life experience satisfying for even the most technologically sophisticated medical students.

Bibliography

Alverson, Dale C., Stanley M. Saiki, Jr., Thomas P. Caudell, et al. 2005. “Distributed Immersive Virtual Reality Simulation Development for Medical Education.” Journal of the International Association of Medical Science Educators 15: 19-31.

Anderson, Terry, and Julie Shattuck. 2012. “Design-Based Research: A Decade of Progress in Educational Research?” Educational Researcher 41 (2): 16-25. OCLC 776668103

Andrade, A.D., Bagri, A., Zaw, K., Roos, B.A., and Ruiz, J.G. 2010. “Avatar-Mediated Training in the Delivery of Bad News in a Virtual World.” Journal of Palliative Medicine 13: 1415-19. OCLC 694448952

Arnold, Stephanie J., and Bogda Koczwara. 2006. “Breaking Bad News: Learning Through Experience.” Journal of Clinical Oncology 24: 5098-100. OCLC 110115544

Black, John B., Ayelet Segal, Jonathan Vitale, and Cameron Fadjo. 2012. “Embodied Cognition and Learning Environment Design.” In Theoretical Foundations of Learning Environments, 2nd ed., edited by David Jonassen and Susan Land, 198-223. New York: Routledge.

Cahan, M. A., A.C. Larkin, S. Starr, et al. 2010. “A Human Factors Curriculum for Surgical Clerkship Students.” Archives of Surgery 145 (12): 1151-7. OCLC 696201278

Chen, Judy F., Clyde A. Warden, David Wen-Shung Tai, et al. 2011. “Level of Abstraction and Feelings of Presence in Virtual Space.” Computers and Education 57: 2126-34. OCLC 742775106

Chow, Meyrick, David Kurt Herold, Tat-Ming Choo, and Kitty Chan. 2012. “Extending the Technology Acceptance Model to Explore the Intention to Use Second Life for Enhancing Heathcare Education.” Computers and Education 59: 1136-44. OCLC 809710772

Consorti, Fabrizio, Rosaria Mancuso, Martina Nocioni, and Annalisa Piccolo. 2012. “Efficacy of Virtual Patients in Medical Education: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Studies.” Computers and Education 59: 1001-1008. OCLC 798159240

Dalgarno, Barney, and Mark J.W. Lee. 2010. “What Are the Learning Affordances of 3-D Virtual Environments?” British Journal of Educational Technology 41: 10-32. OCLC 503324796

Hulsman, R.L., A.B. Harmsen, and M. Fabriek. 2009. “Reflective Teaching of Medical Communication Skills with DiViDU: Assessing the Level of Student Reflection on Recorded Consultations with Simulated Patients.” Patient Education and Counseling 74: 142-9. OCLC 450154949

Lane, C., and S. Rollnick. 2007. “The Use of Simulated Patients and Role-Play in Communication Skills Training: A Review of the Literature to August 2005.” Patient Education and Counseling 67: 13-20. OCLC 442285846

Mantovani, F., G. Castelnuovo, A. Gaggioli, and G. Riva. 2003. “Virtual Reality Training for Health-Care Professionals.” CyberPsychology and Behavior 6 (4): 389-95. OCLC 437807241

Orgel, Etan, Robert McCarter, and Shana Jacobs. 2010. “A Failing Medical Educational Model: A Self-Assessment by Physicians at All Levels of Training of Ability and Comfort to Deliver Bad News.” Journal of Palliative Medicine 13: 677-83. OCLC 649021709

Rosenbaum, M.E., K.J. Ferguson, and J.G. Lobas. 2004. “Teaching Medical Students and Residents Skills for Delivering Bad News: A Review of Strategies.”Academic Medicine 79 (2): 107-11. OCLC 111789963

Thompson, Lisa, and Eric Prommer. Poster presented at the Annual Assembly of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, Denver, CO, March 7-9, 2012.

About the Authors

Susan Lowes is Director of Research and Evaluation at the Institute for Learning Technologies at Teachers College, Columbia University. She has directed evaluations of multi-year projects at the K-12, university, and post-secondary level funded by the U.S. Dept. of Education, the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Environmental Protection Agency, state and local departments of education, and private foundations, and has served on U.S. Dept. of Education and NSF Advisory and Review panels. Dr. Lowes has a Ph.D. in Anthropology from Columbia University and is also Adjunct Professor in the Program in Communication, Computing, and Technology in Education at Teachers College, where she teaches courses on research methods and on online schools and online schooling. She has been the evaluator on several recent initiatives at Hospice of the Valley funded by the Virginia G. Piper Charitable Trust, including this one. She can be reached at lowes@tc.edu.

Gillian Hamilton, M.D., is Vice-President of Education and Innovation at Hospice of the Valley. She is board-certified in hospice and palliative medicine, geriatrics, and internal medicine and holds a PhD in physiological and clinical psychology. At the time of this project, she was responsible for oversight of all education programs at Hospice of the Valley, including those to train residents, hospitalists, nurses, social workers, and chaplains in the principles of palliative care. This program was her brainchild.

Vicki Hochstetler is Director of Education at Hospice of the Valley. She has an M.Ed. in Instructional Technology from Arizona State University. She was the manager of this project.

SeungOh Paek is an Assistant Professor at the University of Hawaii-Manoa and has an Ed.D. from Teachers College, Columbia University. At the time of this study, she was a Research Associate at the Institute for Learning Technologies at Teachers College and did the statistical analysis.

- The phrasing of the second item was different on this survey compared to the previous survey (which asked about “Talking with a patient about death and dying”), so the two modes can only be compared on the one item. ↩

'Teaching Communication Skills to Medical Students in a Virtual World' has 17 comments

November 3, 2022 @ 4:33 am What Are Virtual Beings and How Will They Impact Our World? | Iterators

[…] ego to accept that they aren’t yet perfect. But, feedback is necessary for learning and growth. People seem to prefer feedback coming from an artificial entity than from a real human, so advice from these “non-human […]

June 21, 2022 @ 5:27 am Heed

Nice posts. I am a paramedic student. https://heedhealtheducation-australia.blogspot.com/2022/04/how-to-become-paramedic-heed-health.html

May 23, 2013 @ 10:53 am @dawn_armfield

Teaching Communication Skills to Medical Students in a Virtual World – http://t.co/buFnlVtUo1

May 22, 2013 @ 7:59 am @julie_stella

Good read for med school students in ENG 271W: http://t.co/yJFwqqlhcw

May 19, 2013 @ 4:50 pm @psychopr

Teaching Communication Skills to Medical Students in a Virtual World http://t.co/QKVU76gi6F

May 18, 2013 @ 1:06 pm @ollejanos

Teaching Communication Skills to Medical Students in a Virtual World – http://t.co/i8Wd0dX84m

May 17, 2013 @ 12:57 pm @tryberg

RT @JITPedagogy: Virtual role-plays in #SecondLife train medical students to communicate with patients http://t.co/MkxwvBLtmy http://t.co/GsqLRJSmzW

May 17, 2013 @ 12:46 pm @kimonizer

RT @JITPedagogy: Teaching Communication to Medical Students in a Virtual World by Lowes, Hamilton, Hochstetler & Paek #secondlife http://t.co/MkxwvBLtmy

May 17, 2013 @ 12:45 pm @kimonizer

RT @JITPedagogy: Virtual role-plays in #SecondLife train medical students to communicate with patients http://t.co/MkxwvBLtmy http://t.co/GsqLRJSmzW

May 16, 2013 @ 3:56 pm @thee_emz

RT @JITPedagogy: Virtual role-plays in #SecondLife train medical students to communicate with patients http://t.co/MkxwvBLtmy http://t.co/GsqLRJSmzW

May 16, 2013 @ 2:22 pm @JITPedagogy

Virtual role-plays in #SecondLife train medical students to communicate with patients http://t.co/MkxwvBLtmy http://t.co/GsqLRJSmzW

May 15, 2013 @ 10:43 pm @GridWideNews

RT @JITPedagogy: Can #SecondLife help teach communication skills to medical practitioners? http://t.co/MkxwvBLtmy http://t.co/eS3ofrJHeE

May 15, 2013 @ 3:20 pm @cunycommons

RT @jitpedagogy: Can #SecondLife help teach communication skills to medical practitioners? http://t.co/6xCgD3li5m http://t.co/iGzXS4HCE1

May 15, 2013 @ 2:17 pm @lindsey_freer

RT @JITPedagogy: Can #SecondLife help teach communication skills to medical practitioners? http://t.co/MkxwvBLtmy http://t.co/eS3ofrJHeE

May 15, 2013 @ 2:16 pm @JITPedagogy

Can #SecondLife help teach communication skills to medical practitioners? http://t.co/MkxwvBLtmy http://t.co/eS3ofrJHeE

May 15, 2013 @ 11:59 am @JITPedagogy

Teaching Communication to Medical Students in a Virtual World by Lowes, Hamilton, Hochstetler & Paek #secondlife http://t.co/MkxwvBLtmy

May 15, 2013 @ 11:35 am Introduction

[…] Lowes, Gillian Hamilton, Vicki Hochstetler, and SeungOh Paek collaborated on “Teaching Communication Skills to Medical Students in a Virtual World,” which presents the findings of their research into the potential of virtual role playings to […]