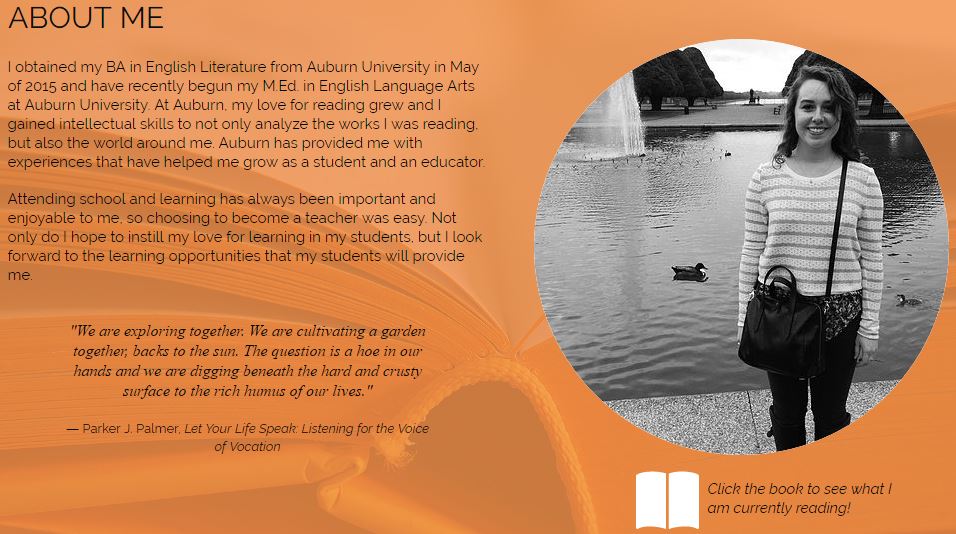

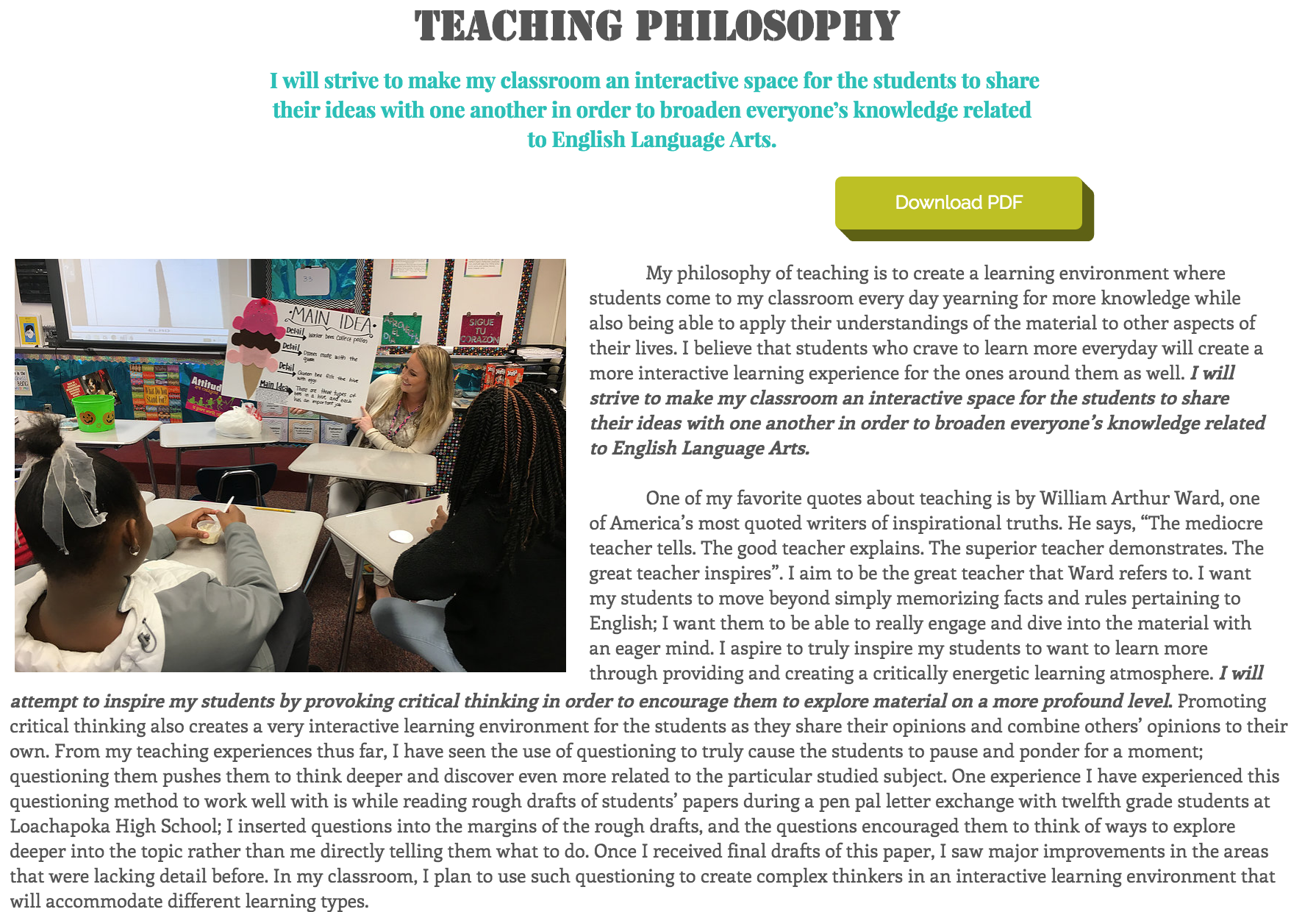

The English Education program initially joined the ePortfolio Project Cohort because they sensed that their students viewed themselves strictly as students rather than as future teachers. Because of the ePortfolio Project’s emphasis on reflective practice, the faculty in English Education saw the ePortfolio as a way to facilitate the difficult identity work of shifting roles. Penny Light, Chen, and Ittelson echo this idea: “The act of being able to represent one’s own learning and, by connection, one’s identity in relation to that learning is the most significant contribution of ePortfolios” (2012, 17). In addition, the professional, outward-facing nature of the ePortfolio invites English Education students to imagine audiences from their not-too-distant future: principals, school boards, fellow teachers, parents, and future students. In their article, “Implementing ePortfolios in English Education: Delights, Dilemmas, and Recommendations,” Auburn faculty member Dr. Brandon Sams and graduate teaching assistant Latasha B. Warner write, “Many students informed us that they had never completed an assignment for anyone other than their instructor and peers […] Students seemed to take [the ePortfolio] more seriously than other assignments because the intended audience is a professional one, specifically administrators in K-12 schools” (2016, 6). Faculty wanted a new way to help students transition from performing a student role to performing a teacher role, and the ePortfolio seemed like a way to do just that. The students below use their About Me page and teaching philosophy to communicate their professional identity.

Joining the ePortfolio Project Cohort was the English Education program’s first foray into formally integrating multimodal composition into their curriculum. While this is probably also true for other Cohort programs, it is particularly important for English Education because they are teaching students not only to understand and create multimodal compositions but also to teach them to middle and high school students. Drawing on scholarship by members of the New London Group, Claire Lauer writes, “Multimodal texts are characterized by the mixed logics brought together through the combination of modes (such as images, texts, color, etc.)” (2014, 24). In the example below, one student integrates multimodal texts into her lesson plan by teaching the text and graphic novel versions of Hamlet. Her reflective writing describes how she hoped to increase student engagement by using two genres instead of one.

English Education just completed their first year of ePortfolio implementation in their program. Because ePortfolios are new to the English Education program at Auburn, faculty are learning how to frame their importance for students. Sams and Warner note,

the need for contextualizing the ePortfolio as multimodal composition; a genre of composing that, potentially, has much to teach teachers about audience, reflection, design, and the interrelationship among image, text, and video. We found it easy to talk about ePortfolio as a vehicle for obtaining employment, a website designed to “represent” one’s skills as a teacher. However, as a multimodal, multimedia form, it is composed using skills that every [teacher] needs to teach. English Education programs need to be prepared to frame ePortfolio as a multigenre compositional form that teachers can use in grades 6-12 classrooms. […] More than just “representing” a student’s pedagogical skills and preparation, the ePortfolio is a constitutive form of those same skills and practices. (2016, 6-7)

Sams and Warner’s assertions also remind those who are implementing ePortfolios to clarify the purpose(s) of the ePortfolio—for themselves and their students. While the faculty in the English Education program have professionalizing aims for their students’ ePortfolios, the primary purpose is not marketing or job-seeking (though they don’t discourage students from using their ePortfolios in this way if they choose to). For the English Education program, the “professionalizing” work is more about helping their students develop their teaching identities and “help[ing] our preservice teachers become knowing professionals” (2016, 5, emphasis in original) than it is about convincing someone to hire them.

Nor is their primary purpose assessment. Though education programs have extensive accreditation and assessment requirements, the English Education program at Auburn doesn’t want to use the ePortfolio for assessment purposes: they are far more interested in the ways it supports 1) teacher identity development by way of reflective practice and 2) teaching, learning, and practicing multimodal composition. In response to the idea of requiring a “standards-based version of ePortfolios,” Sams and Warner write, “we encourage our students to take risks as they select the artifacts that best represent themselves as teachers. In evaluating these, it is clear that, although we do not explicitly mandate that students select artifacts that meet a required number of standards, they are demonstrating their ability to meet these standards on their own. Our students begin to see that, using assignments like ePortfolios, standards are being met and, more importantly, critical thinking, analysis, and creativity are evident” (2016, 6).