The COVID-19 pandemic has forced most teaching and learning to online platforms. At many institutions, this shift has been met with anxiety, frustration, and in some cases stubborn refusal to conform to the virtual realities, limitations, and possibilities that online teaching provides. Many K–12 school districts continue to struggle to equip their teachers to make the shift to online teaching, leaving teachers to fend for themselves (Lambert and Rosales 2020). The shift to a virtual space has also left ill-prepared teachers, parents, and students fatigued (Holladay 2020). Higher education spaces are not exempt from these issues. Some believe the sudden shift to online teaching and learning is having both negative affective and cognitive effects on students as they work to negotiate the newness of it all (Burke 2020). But the fact still remains that the shift online has not removed the racist norms that were normative in face-to-face classrooms.

Cathy Davidson wrote a blog post entitled “The Single Most Essential Requirement in Designing a Fall Online Course.” In her post, she made an impassioned plea for educators to radically change their approach to (online) teaching during fall 2020, in light of all of the things students will be carrying into their classes because of the social situation. She argued that effective fall 2020 teaching required that summer preparation foreground the reality that “our students are learning from a place of dislocation, anxiety, uncertainty, awareness of social injustice, anger, and trauma” (Davidson 2020). Moreover, she added that informed solutions to creating a more humane and student-centered learning environment during the pandemic would mean “being sensitive to the devastating historical moment in which we are now living and offering students a way forward beyond it.” While the year 2020 will certainly go down as a unique point in the annals of history, many Black students would have entered the fall classrooms from a space of “dislocation, anxiety, uncertainty … anger, and trauma” as well as perpetual “awareness of social injustice” even if the COVID-19 pandemic had not occurred. The pandemic merely heightened what has always been there. Black people in the US continue to live in what Saidiya Hartman called “the afterlife of slavery—skewed life chances, limited access to health and education, premature death, incarceration, and impoverishment” (2007, 6). Any way forward that does not account explicitly for the normativeness of anti-Black thinking in education will merely ensure a racist and anti-Black future in education.

Inspired by the words of Cathy Davidson, while at the same time, captivated by the ancestral rhythm of resistance and freedom inherent in blackness (Cone 2018; Moten 2013; Dillard 2006; Morrison 1993), we argue for a deeper response to the current historical moment. In this article, we address Black non-being and exclusion that is the norm for education in general, but online education more specifically, in the US. This conversation is critical for online education because it is an irrefutable mode of all education moving forward and a space ripe with possibility for antiracist innovations that could unbound the limitations of physical classrooms.

What is Critical Black Theory and Why Is It Important for Online Schooling in the US?

For the sake of this article, critical Black theory will be used to zero in on the signification of blackness in historical and contemporary considerations of online schooling in the US. While other critical theories, like critical race theory (CRT), provide in-depth and intersectional analysis on race and racism, critical Black theory, or “BlackCrit” focuses on a “theorization of blackness” (Dumas and ross 2016, 416). BlackCrit is a “metatheory,” used to explicate the hidden whitened discursive context that undergirds and drives most theories, even theories that consider themselves to be “critical” (Wilderson III 2020, 14). Put simply, the goal of BlackCrit is to shine light on the anti-Black soul of the United States: to lay bare the levers that drive the racist, sexist, classist engine of capitalism. BlackCrit provides an avenue to see past the elusive and often confusing racially ambiguous language such as “people of color,” “diverse group” or person, “minority,” or “underrepresented group” when one is speaking explicitly about Black people (Wilderson III 2020, 41). It compels us to name things for what they are instead of using racially ambiguous or colorblind language, metaphors, or figures of speech that mask, under-emphasize, or erase Black pain and suffering. As Fred Moten (2016) eloquently put it, “We can’t go around this. We gotta go through this” BlackCrit argues that the keys to being liberated out of this racial caste system is acknowledging that it still exists; that the episteme and libidinal nature of the plantation continues unhindered and fundamentally shapes society.

At the same time, BlackCrit also speaks to the ways that blackness signifies a being and deep embodied knowing. Fred Moten (2013) argued that there lives a rich and emancipating hope out of the hopeless condition in understanding blackness. Moten believes that in the signification of blackness outside of the discourse of humaneness, and therefore the realm of being, theorizing blackness exceeds understanding and therefore cannot be reduced to a single thing. Its rich, unmappable essence carries with it the “absolute overturning, the absolute turning of this motherfucker out” (2013, 742). Therefore, BlackCrit forces a consideration of what is possible out of the binary and either/or constraints inputted by a white western colonial imaginary and instead invites an orientation that positions being and knowing as circular (Spillers 2003). Online learning remains an uncharted and underutilized discursive space for addressing anti-blackness and engaging in antiracist praxis (Asenbaum 2019; Bonilla and Rosa 2015; Bondy, Hambacher, Murphy, Wolkenhauer, and Krell 2015; Guthrie and McCracken 2010). In fact, decolonizing and antiracist visions are already embedded within the colonized racist machines of online learning (la paperson 2017; Collins and Bilge 2016).

Online Classrooms Are Not Race-Neutral: How Online Education Eludes Race

The use of technology as a mode of learning has been a part of the US educational infrastructure since the beginning of the nineteenth century (Reiser 2001)—a beginning during which it was criminal for Black people to be formally educated. In the US historically, schoolhouses were created by power-holding whites to sanction and reify anti-Black racism, sexism, white Anglo-Saxon Protestant values, and later prepare a docile workforce to maintain economic disparities (Rury 2009). While American society has come a long way from nineteenth-century schools, traditional public schools have fundamentally maintained nineteenth-century learning practices and structures committed to anti-blackness.

In a historical overview of the structure of schooling between 1890–1900, Larry Cuban reminded educators “the apparent uniformity in instruction irrespective of time and place appears connected to the apparent invulnerability of classrooms to change” (1995, 1). Cuban identified minuscule change in the structures of schooling over time and observed that innovation in schools tended to be reserved for a subcategory of students such as the gifted, but not implemented with the main population (1995). Cuban’s analysis neglects to detail the ways schools’ documented invulnerability to change maintains anti-blackness in structures, curricula, and personnel. These realities are transposed into online learning environments and digital learning tools that are assumed to be race-neutral. For example, Borje Holmberg formed a theory of distance teaching that advocates for personalized distance education but avoids the ways race informs individual learners, tech tools, or online environments (1995). The major players in online education still hold tightly to racist Enlightenment ideals of rugged individualism and the belief in the disembodied articulation of the self (Asenbaum 2019). In other words, white supremacy and its chief actor, whiteness, still maintain a hegemonic hold on online learning. More explicitly, race-neutral language transposes whiteness to educational technology as normative, reifying that white people are the standard for humanity, thus relegating blackness to sub-human. Online education operates with race-neutral rhetoric that obscures how race informs everything.

Despite the prevalence of anti-blackness in online education, collaborative technology platforms like Twitter, Snapchat, and Facebook have provided disruptive spaces of resistance due to their ability to transcend traditional forms of networking and collaboration. This is largely due to these technologies’ user-centered platforms, which allow users to design social communities and develop and disseminate their own innovations. Facebook and other Web 2.0 collaborative platforms have become impactful spaces to negotiate and transform the traditional “boundaries of the classroom,” where the teacher directs and designs all learning and students merely respond to often irrelevant, dated content within the confines of the physical classroom space (Dennen 2018, 239). Disruptive social media platforms on the other hand allow learners to design thinking, select relevant topics of interest, and engage in expedient dialogue and response to real world issues. For example, with the widely-publicized killings of unarmed Black people at the hands of law enforcement and security personnel—Daunte Wright, Rayshard Brooks, George Floyd, Breonne Taylor, Atatiana Jefferson, Trayvon Martin, Philando Castile, Tamir Rice, Yvette Smith, Rekia Boyd, and Botham Jean, and Michelle Cusseaux, just to name a few—people form across the globe organized through online activism to resist racial injustice. Online activism is indicative of the power of digital tools to fight racism, yet online education broadly has yet to seriously move toward antiracist pedagogies.

Valcarlos, Wolgemuth, Haraf, and Fisk (2018) queried all peer-reviewed articles from the past 11 years to ascertain the presence of anti-oppressive pedagogies in scholarship related to online education. Of three thousand articles, they found ten that dealt specifically with anti-oppressive pedagogies in online education. Out of those ten articles, four common themes emerged: legitimizing students’ epistemologies (personal narratives, emotions, and culture), requiring reflection and discussion, establishing expectations of critical awareness, and democratizing educator and student roles (351). With the exception of these articles, the online learning community has been almost mute on critical social justice concerns (Valcarlos, Wolgemuth, Haraf, and Fisk 2020). Even fewer articles explicitly name the role of antiracist pedagogy in online education.

Bridging the Gap: The Potential of an Antiracist Future in Online Education

The absence of specific mention to antiracist pedagogies in the extant literature and theory of online education is emblematic of the normativeness of anti-Black racism and white normativity in online education. A corrective is essential to equip students with the requisite forms of racial literacy to constantly reflect upon their world in a responsible manner (Tarrant and Thiele 2014). Racism is a system of historical oppression that is built on an hegemony of power and domination that privileges certain groups as inferior to the dominant group (Harrell 2000). In the hegemony of racism, certain ideas shape the construction of the constituent parts of society (business, education, law, and medicine) and give rise to accepted behaviors and belief systems (Gramsci 1989). To be neutral on racism is to be complicit in racist ideas; there is no in-between (hooks 1994; Kendi 2019). In what follows we will provide a framework for thinking through an antiracist pedagogy for online education.

We take up Zachary Casey’s (2016) framing of pedagogy to help shape our understanding of an antiracist pedagogy. In his book, A Pedagogy of Anticapitalist Antiracism: Whiteness, Neoliberalism, and Resistance in Education, Casey defined pedagogy as an action to “foster (political, partial, humanizing) learning, in ways that acknowledge the political nature of human interactions and the varying context(s) in which we live” (18). Shaped by the liberatory visions of Paulo Freire, bell hooks, Audre Lorde, and others, Casey argues that every choice is political: that each action, each choice we make requires making particular judgements and conceptualizations about reality and knowledge that emanate from our ethical framework. An antiracist pedagogy acknowledges the political and partial nature of teaching; there is no such thing as neutrality. When we separate our being from our doing, our knowing from our doing, we are adhering to a racist, colonialist imagination. How we teach is a byproduct of how we were taught to view the world.

David Gillborn posited that “Anti-racism has not failed—in most cases; it simply has not been tried yet” (2006, 17). He observed that antiracist work in education arose as a response to the performative liberal practices used to serve Black children and their families but were deeply conservative in nature, contained no awareness of the systemic nature of oppression, and were actually rooted in deficit perspectives of Black people. Antiracism work is about dismantling racism, but it is much more than that. Racism takes many forms and so antiracist actions must be flexible and constantly adapt to the complex nature of reality. To be antiracist means to constantly be about the work of dismantling the racist ingrained nature of teaching.

Nevertheless, without a clear framework for antiracism, the use of antiracism becomes empty rhetoric, what Sara Ahmed (2004) calls non-performative. Often, antiracist statements themselves become the only actions that an institution takes. Or they become the very barrier to developing an antiracist ethos in an institution or classroom and provide no actionable way to diagnose racist versus antiracist praxis. When this happens, explicitly naming racist practices, and examining complicity in racist ideas become non-existent because the institution and the people in it have branded themselves as antiracist. To continue calling the institution racist after the institution has made a commitment to being antiracist becomes undesirable. Likewise, racism then becomes the boogey woman. No one wants to utter its name. But taking up antiracism is a process not a destination. You can act in antiracist ways one day and the next day act in racist ways or uphold racist ideas (Kendi 2019).

Antiracist education accepts the presence of bias and stereotypes but requires employing diligent and consistent investigation into the source of racism and how racist ideas manifest structurally, culturally, politically, and interpersonally (Troyna 1987; Collins 2017). An antiracist pedagogy for online education begins with creating spaces that bring attention to race, class, gender, and ability. An antiracist online environment begins first with an articulation of online learning as an embodied digital discursive space. In other words, enacting an antiracist pedagogy in online learning begins in the body. It requires students and teachers alike to bring their full selves (this is a collective self, not an individual self) into the online learning environment (Dillard 2006).

Specific Antiracist Pedagogies for Online Education

In this section, we describe classroom practices, activities, and experiences we employ in our online classrooms as examples of antiracist pedagogy for online education.

Showing up and the power of the aesthetic: Jazz, freedom dreaming, and liberatory teaching

In each of my (David’s) courses, I start with an artifact exercise that can be done synchronously on the first day of class or asynchronously using a video platform such as Flipgrid or YouTube to facilitate sharing, and a discussion board prompt to debrief the activity (Figure 1). The artifact exercise is also coupled with several modes of engagement: pre-course survey, at least two readings that provide context for a discussion on identity, a related video, and a few thoughts that foreground group values for the course. Providing this level of scaffolding for the artifact exercise is essential to create an environment that encourages authenticity and transparency and ensures students have adequate context for the ensuing dialogue. This exercise serves multiple purposes. First, it is an icebreaker, an opportunity for students to ease into the new semester and get to know each other. Secondly, the goal of the exercise is to foreground very early in the course that teaching and learning are not neutral acts. That to show up in embodied ways means to give attention to the weight that your raced, gendered, and classed selves takes up in the classroom. This exercise invites all parties involved to see each other in embodied ways (Hill 2017).

Finally, the activity is an opportunity for students to share something from their life-world that is important to them and reveals an aspect of their culture they believe is important for our sacred learning experience. For example, after everyone has shared, I invite the class to identify connections or themes across the shared stories. After the connection phase, I emphasize the uniqueness and interconnected nature of our stories. I also point to how the stories reveal values passed down to us and therefore the “presence” of our ancestors;many students actually share pieces of jewelry and pieces of cloth that were given to them by their now deceased grandparents and great grandparents. I inform students that the fact these values still shape how we will interact and engage content in the course is what makes the learning environment sacred and also a space of potential conflict.

The types of artifacts that students bring are often connected to certain values their parents, grandparents, and others have passed down to them. These values and worldviews shape how the students engage each other and make sense of course material—this point is also consistently made by students as they share during the artifact exercise. For example, in one of my classes I had a student share an artifact from a grandparent that emphasized the idea of collectivity. In that same class, another student shared an artifact that a great aunt gave them which reinforced the value of individualism—the exact words were, “pulling yourself up by the bootstraps and getting your work done.” Both students offered conflicting values that were central to their unique worldviews and approaches to learning. The artifact exercise makes it explicit that the online classroom experience is an intergenerational contested space full of imaginations, images, cultures, and values that shape the ontological, epistemic, and ethical visions of the learning space for the teacher and students (Sheppard 2017). The intergenerational contested reality of the classroom necessitates that cultural wars are constantly being waged, most of them occurring undetected behind the scenes.

Antiracist pedagogies are anticipatory in nature. To be antiracist is to anticipate and welcome conflict as a companion in the learning process. As conflict occurs, antiracist pedagogues must be intentional in explicitly naming what is happening. In the example above with the two students, I used their examples to invite students into a connections and synthesis phase of the artifact activity where we engaged in dialogue about issues of identity, power, and perspective taking—we reference the articles they would have read before class to support this movement—in order to understand and draw connections between the values expressed by students and the ways of knowing and being that are privileged in education (e.g. rugged individualism vs. collectivism).

I also begin each class session with approximately five minutes of an invocation. The invocation experience—which is actually done first at the very beginning of class—and the artifact exercise flow together to concretize the sacredness of our collective learning task and the fact that learning is an intergenerational experience. One of the amazing Black women in my research who identified as womanist first introduced a “pedagogy of invocation” to me (Humphrey Jr. 2020, 93). Often this first five minutes will consist of a song, something soulful and rhythmic like Nina Simone’s “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free” or Thelonious Monk’s “Round Midnight.” Invocation simply means to invoke someone or something for assistance or authority. In the Black prophetic tradition, this act is used to acknowledge that what we are about to embark upon is bigger than ourselves. That we are not alone in this moment. That this moment is fixed in dialectical union with the present and future. That we bring our full selves (a collective self) into this space including our mind, our body, our memories, dreams, and the sacred witness of our ancestors (their lessons passed down to us, both good and bad, whether we want to admit to it or not and whether we realize or remember these messages or not). During the invocation, I instruct students to do the following: “Please take this moment and listen to the words, rhythm, and melody of the song. Meditate on what you are hearing; be sensitive to what your mind and body are saying to you as you listen. After the song concludes, we will begin our collective task.” After the second or third class, I invite students to share their favorite songs and lead the invocation. I always bridge the mindfulness moment with the course content of the day. While most effective in the synchronous online class, this activity can be adapted for asynchronous learning environments by posting the invocation as a required first task in a module using YouTube or any other video platform that allows you to pre-record video and a discussion post-feature.

Collaboratively innovating content with students

By pairing collaborative digital tools with contemporary, relevant racial justice content through an embodied pedagogy, online education can become antiracist. An effective antiracist approach in online learning is to connect all content to the racialized reality every student and teacher is traversing. In my classroom, I (Camea) do this by inviting students to make real-world connections between course content and racial justice. This is central to my antiracist teaching strategies and not a cursory exercise or attempt at culturally relevant gimmicks (Love 2019). This is exemplified in my online spring 2021 doctoral qualitative research methods course titled, “Critical Ethnographic Methods for Social Justice Research,” in which student researchers used critical ethnography research tools to design research studies that contributed to changing conditions toward greater freedom and equity; to amplify minoritized participant experiences; and to humanize the research act. This course was created in response to COVID-19 and the anti-Black violence and other social unrest occurring in the US, and was delivered synchronously with weekly meetings on zoom. In this course, students were invited to make sense of their own racial identities by exploring researcher positionality, rapport with research participants in the field, and accessing and exiting the field.

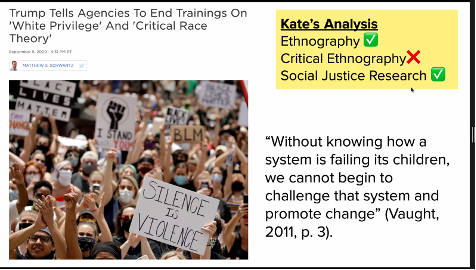

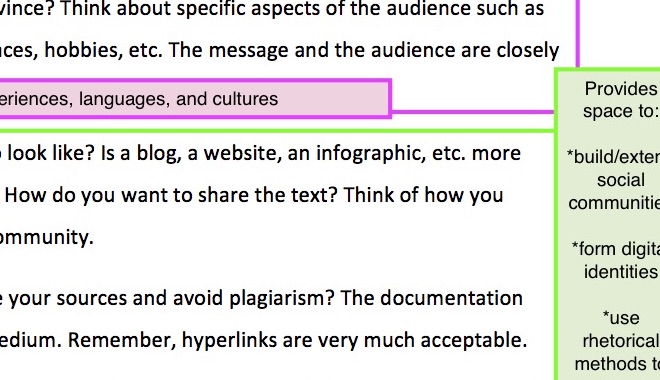

For example, a white woman student researcher in a midterm presentation made connections between the 2020 presidential executive order banning critical race theory in federally funded trainings and the critical ethnographic research to demonstrate that the latter was an effective example of social justice research. Figure 2 is a screenshot from the student’s Zoom presentation that details her analysis. In doing this presentation, the student researcher reflected on her own whiteness and how it informed the choice of book she selected for her midterm and how it impacted her positionality as a researcher. By inviting student researchers to make connections between the course content, themselves, and the real world in class, I created space for authentic engagement with race and racism, and allowed students to innovate paths towards antiracism. This is the work.

The pedagogical elements of the assignment design and the creation of a classroom community that could hold this type of learning were grounded in student choice, criticality, and a learning community where students were safe to introspectively reflect on how race impacts all we do and learn.

Creating an antiracist online-class Zoom ethos

Additionally, when attempting to employ antiracist pedagogy in an online context it’s imperative that the ethos of the digital space exude the brilliance and intellectual rigor of Black and other minoritized peoples and cultures. The class ethos is apparent by the way students are made to feel. My online courses center an ethos of Black creativity by playing an upbeat song from various Black music traditions such as hip hop, pop, neo-soul, or gospel as students log onto Zoom. During this time the music plays in the background and students welcome one another verbally or in the chat. This is a tone-setting exercise that grounds the space in Black aesthetics to communicate that Blackness is celebrated here. The songs are not discussed; they just exist like the wall decor in a physical classroom. Similarly, when I use slides (which is rare because my pedagogy is dialogic and interactive in nature) I intentionally use slides that have artwork of Black and Brown faces and use cultural icons in the designs. Again, this is an aesthetic choice that communicates that celebrating Black culture is a part of how we do everything; nothing is race-neutral. This practice invites students to feel safe to share their own cultural artifacts when they present.

Furthermore, I co-create an antiracist class-zoom ethos with students by setting norms that are particularly valuable for antiracist praxis such as: “own our subjectivity,” “challenging each other with respect,” and “ question your own lens/perspectives without fear.” These norms are essential to disrupt the notion that race is a taboo or scary topic in the classroom. Likewise, I lead the class agenda from an Africanist (King 2019) perspective of time grounded in abundance. I remind students there is always enough time. In my fluidity I use a structure that always includes space for intuition and possibility. I require all cameras be on during discussion therefore I can gauge if students are confused, excited, or tired, and I always have the time to respond to those human aspects of their learning in the moment.

My class-zoom ethos is strengthened because students are positioned as co-facilitators.The syllabus includes student voice and choice in each assignment and each student is required to co-facilitate a discussion. Students are encouraged to fuse their own identities and interests with interactive technological tools. For example, one bi-lingual Latinx student used www.getepic.com to share the children’s e-book “Salsa” by Jorge Argueta, which depicted visual art and a “cooking poem” about a Mexican-American family creating salsa as a metaphor for engaging Mexican-American research participants. The student screen-shared the e-book pages and read the book to the class in Spanish unapologetically to model the purpose and need for research participants being their authentic selves. Beyond the content of his presentation, the fact that this doctoral student felt safe and welcomed enough to share his home culture and language is evidence of an embodied pedagogy from which all learners can grow.

Conclusion

To thrive in the afterlife of COVID-19, abnormal environmental disasters, and the continued murdering of Black bodies, all education—especially online education—must become antiracist. Neither online education nor digital tools are exempt from the deeply anti-Black racism that are the bones of US education systems. Educators in online contexts collaborating with students are well-positioned to create digital learning spaces that intentionally (above all else) work to eradicate the insidiousness of racial violence perpetuated through the myth of race-neutral learning theories and pedagogical practices.

This is great teaching for all students. We use BlackCrit to guide this discussion, we invite our readers to understand that the imaginative resistance and freedom in blackness is a guiding light for all educators and learners in all contexts. In the spirit of Dubois, we believe that addressing the issues that perpetuate racism and anti-blackness are the key to liberating all humanity. The pedagogical principles shared in this paper are meant to reconcile the disembodied nature of online education as it exists.

Writing as two scholars who frequently facilitate antiracist spaces occupied by white colleagues, we anticipate the oppressive question, “Can white people use these pedagogical tools?” We invite these well-intended inquirers to ask themselves what about their socialization and relationship to teaching and learning prompts them to center whiteness? Moreover, we point out this question is never asked about white scholars or scholarship that originates from Eurocentric locations. What if the answer to this question was grounded in decentering whiteness? Instead of needing to center anything and employing hierarchical language, we challenge (online) educators to think interstitially (Spillers 2003). This invites a vision of learning that is not governed by power but is motivated by humanizing the community through an embodied teaching approach.

We can’t afford to wait. The future started yesterday and we’re already late.