Introduction

Achieving and maintaining consistent student engagement can be difficult in online learning contexts (Kizilcec and Halawa 2015; Allen and Seaman 2015, 61; Greene et al. 2015). There are many factors that impact learner engagement: course structure, amount of lecture time, user experience of the learning management system, and countless other variables. However, online educators and scholars of online learning have consistently found evidence that peer interaction and learner-instructor interaction are strongly related to learner engagement (Bryson 2016; Garrison and Cleveland-Innes 2005; Greene et al. 2015; Richardson and Swan 2003; Yamada 2009). Several studies have found that measures of social presence, a theoretical construct originating from communications studies, are significantly related to learners’ overall outcomes and perceived experience (Richardson and Swan 2003). Social presence refers to how “salient” an interpersonal interaction is—how readily one feels like they are “present” with another.

To achieve high social presence between students, researchers have discovered that the modality of online communication is extremely important (Yamada 2009; Kuyath 2008; Johnson 2006). The modality of communication refers to the types of channels used: text chat, forums, voice chat, video conference, etc. In communications, human-computer interaction, and online education literature, it has been shown that richer modes of communication between conversing members lead to higher rates of trust, cooperation, engagement, and social presence (Bos et al. 2002). For example, video conference, which includes real time video and voice, is a richer mode of communication than asynchronous forums, and has been shown to lead to higher rates of cooperation than text chat (Bos et al. 2002).

These advances provide strong evidence that the interaction patterns of people carry rich signals that correlate with a variety of outcomes important to personal growth, learning, and team success. By using modern machine learning methods and statistics of conversation patterns—who spoke when, for how long, etc.—even without knowing the content of these conversations, researchers have been able to predict speed dating outcomes, group brainstorming success, and group achievement on a test of “collective intelligence” (Pentland et al. 2006, Woolley et al. 2010; Dong and Pentland 2010; Jayagopi et al. 2010; Kim et al. 2008; Dong et al. 2012a, 2012b). By developing more sophisticated computational models of human interaction, it is possible to infer social roles, such as group leaders or followers (Dong et al. 2013).

Current study

To show the effectiveness of online learning systems that contribute to strong learning outcomes and learner performance via tools that foster participation and interaction, we present an experimental study in this paper conducted with an online class. Our learning platform, which is used to conduct our experiments, allows students to interact using video chat and text chat. In addition, students get continuous feedback on their participation and engagement in the video chat via a tool we named Meeting Mediator (MM). MM essentially provides feedback on how the class participant is doing in terms of measures of engagement such as speaking time, turn-taking, influencing or affirming other participants, and interrupting other speakers.

The Meeting Mediator integrated into our online learning platform is a further enhancement of the concepts and ideas introduced by Kim et al. (2008), who implemented a similar user feedback mechanism in a face-to-face setting with data collected via sociometric badges worn by users interacting in small groups. Our platform includes a new version of the MM, which introduces new metrics for key conversational events such as interruptions and affirmations. In this study, we validate the effectiveness of this online MM through a number of experiments we conduct.

Part of the innovation at the core of our study is the burgeoning science of quantitatively analyzing human social interaction. This small but exciting subfield of computational social science has shown immense promise in developing machine understanding of human interaction (Woolley et al. 2010). By instrumenting many different types of communication, such as face-to-face physical conversation, video conference, and text chat, researchers have been able to predict group performance on a variety of tasks.

Though this study was conducted prior to the 2020 pandemic, the challenge presented to the team carrying out the experiment was to understand the factors contributing to successful transition of programs to online environments. The platform was designed to foster virtual engagement, providing course developers and instructors new tools for offering online experiences likely to capture and keep learner interest. This is especially critical in a time when the pandemic has forced millions of students and professional learners around the globe to use online platforms, replacing the traditional in-person instruction.

An important point to emphasize is that we do not make a claim to replace in-person learning with technology-enabled online learning. We acknowledge that remote instruction may present certain technology-driven features and advantages, but there are many ways in-person instruction provides a superior learning experience. Through the experiments we conduct in this study and our findings, we contend that the remote learning experience can be enhanced and the gap between in-person versus online learning can be bridged to some extent using real-time feedback mechanisms such as the Meeting Mediator and interaction metrics. This is clearly good news in times of a pandemic like COVID-19, where instructors as well as learners are challenged in many unique ways.

Materials and Methods

We first describe our user-facing applications, supporting backend tools and the metrics we designed and employed for performance assessment. Then, we present our experiment design.

The Riff Platform and its user-facing applications

Our team developed three foundational user-facing applications and supporting backend tools as part of the Riff Platform. These are:

- Video Chat (with Meeting Mediator)

- Post-Meeting Metrics

- Text Chat (which includes Video Chat and Post-Meeting Metrics)

These applications and tools were built for both commercial and research purposes, cloud-deployed in standardized ways, but customized over time to meet the changing needs of Riff customers and modified research goals. (An open version of Riff Video Chat, called Riff Remote, is available here: https://my.riffremote.com/.)

Video chat

Riff Video Chat (Figure 1) is an in-browser video chat application that uses the computer’s microphone to collect voice data for analysis and is present in all manifestations of the Riff Platform. Riff Video does not require plug-ins or a local application in order to run—participants navigate to a URL (either by entering it directly into the address bar or through an authenticated redirect from another application), enable their camera and microphone, and then enter the video chat room. Other features of the video chat include screen sharing, microphone muting, and the ability to load a document (typically one with shared access) side-by-side with the video on screen.

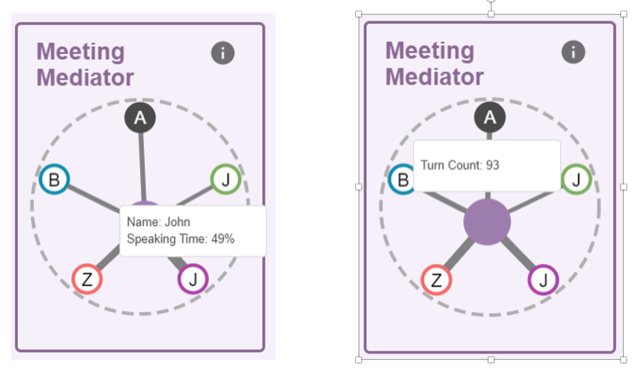

A key element of Riff Video is the Meeting Mediator (MM) (Figure 2), which gives participants of the video chat real-time feedback about their speaking time. Specifically, it provides three metrics:

- Engagement, as indicated by the shade of purple of the node in the middle of the visualization, which shows the total number of turns taken in running five–minute intervals throughout the chat—dark purple means many turns; light purple means fewer turns;

- Influence, as indicated by the location of the purple node, which moves toward the person who has taken the largest number of turns in running five–minute intervals throughout the chat;

- Dominance, as indicated by the thickness of the grey “spokes” running from the central purple node out to each of the participant nodes, which indicates the number of turns people have taken in running five–minute intervals.

These metrics are continuously updated throughout the video chat, lagging one or two seconds behind the live conversation. In a meeting, this tool acts as a nudging mechanism, which is essentially an intervention by the system aimed at increasing a participant’s self and situational awareness, influencing a participant’s behavior towards a more rewarding learning experience and outcomes. The MM indirectly encourages users to maintain conversational balance by speaking up (if the user sees they have not spoken recently) or to engage others who have not been as active in the conversation.

Post-meeting metrics

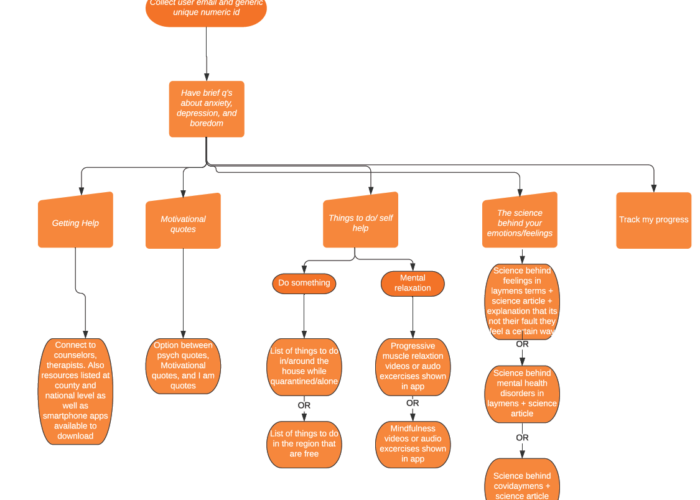

Immediately after a Riff Video Chat meeting, Metrics (Figure 3) appear on screen to show participants measures associated with the meeting, specifically:

- Speaking Time—a chart showing the percentages of turns taken by each participant;

- Pairwise Comparisons—each of the following charts shows the pairwise comparisons of the individual participant with respect to each other participant, to show the balance of each pair in their interactions:

- Influences—a chart showing who spoke after whom in the video chat, which aggregates data across all types of spoken events;

- Interruptions—a chart showing interruptions (when someone cuts off another person’s speaking turn);

- Affirmations—a chart showing affirmations (when someone has a verbalization, but does not cut off another person’s speaking turn);

- Timeline—an interactive view of the video chat meeting over time, on top showing what time each participant spoke and below when each pairwise interaction took place (“your” and “their” interruptions, affirmations, and influences).

Additionally, each user can access their past history of meetings at any time, independent of the video chat itself (Figure 4).

Text chat

Riff Text Chat (also known as Riff EDU) is an environment that allows people to text chat with one another in open channels, private channels, and direct messages (Figure 5).

Riff EDU is built on top of the Mattermost platform, which is an open-source project (https://mattermost.com/). The Riff team developed a customized version of this platform which has three key additions (and several smaller modifications):

- LTI integration, which allows the learner to move seamlessly from their learning environment (Canvas, Open edX, etc.) using the learning tools interoperability (LTI) protocol for authentication;

- Video integration, which allows the learner to start an ad hoc video chat session from the Chat environment;

- Metrics integration, which shows the learner views of their video meeting metrics within the Chat environment, as well as additional text chat data and recommendations.

Learner data privacy

At the outset of the course, learners were asked to consent to have data collected about their activity and performance. No learners declined to have data collected about them. Data collected during this experiment was shared directly with learners through the Meeting Mediator and Post-Meeting Metrics page. Everyone in a video chat got access to the data about their conversation, but video and text chat data was not shared with anyone else during the experience. Data analyzed for the purpose of the experiment was anonymized to preserve the privacy of participants.

Supporting accessibility

The experimental environment was designed to account for participants with accessibility needs. Following the WCAG 2.0 AA accessibility standard from the W3C (World Wide Web Consortium 2021) the software underwent an accessibility audit to identify potential issues, which were then remediated before the platform was released to learners. Accessibility compliance was documented using a publicly available Voluntary Participation Accessibility Template (Riff Analytics 2021). Though we did not have any students who let us know that they had specific accessibility needs, we were prepared for that eventuality.

Experiment design

To show the effectiveness of our video conferencing environment and our nudging tool, the Meeting Mediator (MM), we conducted an experiment with a major client of Riff Learning Inc. in Canada. In this experiment, test subjects were recruited to participate in an online course called “AI Strategy and Application” from a government subsidized incubator of tech companies headquartered in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Students elected to take the course as a professional development experience, driven by interest in learning how to start an AI initiative either as an intrapreneurial or entrepreneurial activity. In most cases, the learners were paying for the course, but in some cases, either the course had been paid for by their employer or they were given free access to the course. Learners were either students in advanced degree programs or full-time professionals taking the course as a supplemental learning experience.

The eight-week course was delivered on the Open edX platform with the Riff Platform serving as the communications and collaboration platform for instructor and learner interactions, both structured and ad-hoc. Learners had opportunities to view videos and read original materials on how AI is applied to business problems, tackle hands-on coding exercises to learn basic machine learning techniques in a sandbox environment, and take assessments at the end of each learning unit.

The participants were divided into groups throughout the course to facilitate the following two types of activities:

- Brainstorming activities (in pre-set groups of four to six people)—Each week during the first four weeks of the course, people met on video in their Peer Learning Groups (PLG) to collaborate on the assignment, and then create a shared submission.

- Capstone project collaboration (in self-selected groups of four to six people, plus a mentor)—Each week during the last four weeks of the course, people met on video in their Capstone Groups to collaborate on developing a venture plan based on the winning pitches submitted by their peers in the course.

Learners were left to schedule video meetings with their group members on their own, and the course was time-released (one week of material at a time), but self-paced. However, the course support staff did participate in the first meeting of each group, to ensure that people didn’t have any technical issues and could make the video chats happen without issue.

The main goal of our experiment was to analyze the relationship between using video and text chat, and various outcomes among learners in the course. Furthermore, we aimed to analyze differences, if any, between early users (those who completed at least the first half of the course) versus the rest, to understand the effects of early usage on retention and grades.

Note that in this experiment, the Meeting Mediator (MM) was always present for video chats. Our rationale for that choice was that if our hypotheses that video with MM is positively correlated with any of performance, persistence, or satisfaction in online courses, then having it present for some students and not for others in a paid, graded learning experience might disadvantage the control population and be deemed inequitable.

In our experiment, we set out to test a number of hypotheses and hence show the (positive) relationship (or its lack thereof) between the use of video and various outcomes. Specifically, we explored the following questions:

- Did students who used Riff Video Chat (and Meeting Mediator) more often receive higher grades in the course?

- Did students who used Riff Video Chat (and Meeting Mediator) more often complete the course at a higher rate?

- Is there a strong positive association between participating in additional Riff Video Chats during the first four weeks of the course and earning a certificate?

- Is there a strong positive association between participating in additional Riff Video Chats during the first four weeks of the course and receiving higher grades at the end of the course?

- Is there a strong positive association between participating in additional Riff Video Chats during the first four weeks of the course and completing more of the optional course assignments?

- Is there a strong positive association between participating in additional Riff Video Chats during the first four weeks of the course and pitching a capstone project topic?

The first two research questions are explored for students who completed the entire course (n=62); we removed the chat records and performance output results for students who dropped part way. The remaining questions are explored for the entire cohort students of n=83. These students all started the course, but some of them dropped out and, hence, did not receive a final grade for completion or a certificate.

In our analysis of our experiment results, we used the following three constructs for reporting and interpreting our figures: correlations, odds ratios, and significance. For definitions of these metrics and their implications for our study, we refer the reader to Appendix B. With correlation analysis, we would like to further note that while one may observe the degree to which people who do one thing more (e.g., use video chat) also tend to do something else more (e.g., receive higher grades), such a relationship cannot be directly used to imply causality; they are merely indicators that two phenomena occur together (in a positive or negative relationship) or not.

Finally, we conducted an exit survey for all students who completed the course and a separate survey for those who failed to complete it. While the results of this survey are not directly related to the quantitative analysis we report in the next section, they do provide some qualitative feedback from users on the efficacy of the Riff Platform. We have included the list of survey questions and some key results we collected from these surveys in the Appendix.

Results

In this section, we report the results of our experimental study for students who participated in the course for its entire duration (questions 1–2, n=62) and for all students who started with the course, even if they dropped out (questions 3–6, n=83) separately.

Results for questions 1–2 for students who completed the course

To answer the first question in our study (“Did students who used Riff Video Chat more often receive higher grades in the course?”), we considered the following output variables:

- Final grade earned

- Coding exercise grade

- Capstone exercise grade

- Collaboration exercise grade

- Pitch video completion

For the second question (“Did students who used Riff Video Chat more often complete the course at a higher rate?”), we simply considered whether or not the student earned his/her certificate of completion in the course.

The following table, Table 1, shows the correlation between each output variable listed above and the input variable of “video calls made,” which is the number of times a student connected to the video chat. The p-values were further corrected using Holm’s method to maintain a FWER of 0.05. We find that all p-values are significant at 95% confidence level or better, and correlation values point to reasonably high levels of relationship with most of the output variables.

| Attribute | Correlation to # Riff Calls Made | n | p | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final Grades | 0.50 | 62 | 1.56e-04 | *** |

| Coding Exercise Grades | 0.41 | 62 | 2.54e-03 | ** |

| Capstone Exercise Grades | 0.49 | 62 | 1.56e-04 | *** |

| Collaborative Exercise Grades | 0.27 | 62 | 2.94e-02 | * |

| Pitch Video Completion | 0.37 | 62 | 5.25e-03 | ** |

| Certificate Earned | 0.50 | 62 | 1.56e-04 | *** |

*p < 0.5, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

We further calculated the odds ratio for two of these variables, as shown in Table 2. Here, in addition to the “Certificate Earned” binary variable, the “Grades” variable was created as another binary variable indicating the student has received (or not) a passing grade based on his/her final grade.

| Attribute | Odds Ratio | n | p | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grades | 1.23 | 62 | 16.92e-03 | ** |

| Certificate Earned | 1.35 | 62 | 3.964-04 | *** |

*p < 0.5, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Table 2 with odds ratios greater than 1.0 suggests that spending additional time with video chat increases the likelihood of earning a passing grade and a final certificate of completion (see the Discussion section for more details).

We further illustrate the relationship between these two variables and our input variable (“video calls made”) in Figures 6 and 7. The figures display positively sloped trends which confirm the positive correlations reported in Table 1. That is, as the learners spend more time with video chat, they are more likely to earn higher grades and a certificate of completion.

Results for questions 3–6 for all students

We explored the remaining research questions regarding the early usage (first four weeks) of Riff Video using data we collected from all students in this course. We note again that some students completed the course only partially and dropped out. They did, however, complete the first four weeks of the course. Here we used the start of the Capstone Project as the cutoff date for tracking how often the students were present in channels in which video chats were offered. We correlated this variable to the same performance variables we considered in the previous section to explore the research questions 3–6:

Tables 3 and 4 show the correlation values between the variables similar to the way they are presented in the previous section. All correlations were computed with Pearson’s method, and p values were corrected again using Holm’s method to maintain a FWER of 0.05. We find that not only are the correlation values in Table 3 generally higher than those in Table 1, the p-value significance levels are also stronger. Furthermore, higher odds ratios in Table 4 suggest that early video chat usage is even more determinant in achieving successful performance in the course.

| Attribute | Correlation to # Riff Calls Made | n | p | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final Grades | 0.54 | 83 | 5.40e-07 | **** |

| Coding Exercise Grades | 0.42 | 83 | 5.22e-05 | **** |

| Capstone Exercise Grades | 0.50 | 83 | 3.89e-06 | **** |

| Collaboration Exercise Grades | 0.52 | 83 | 2.07e-06 | **** |

| Pitch Video Completion | 0.45 | 83 | 3.95e-05 | **** |

| Certificate Earned | 0.50 | 83 | 3.89e-06 | **** |

*p < 0.5, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p<0.0001

| Attribute | Odds Ratio | n | p | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grades | 1.79 | 83 | 1.03e-04 | *** |

| Certificate Earned | 2.00 | 83 | 1.96e-05 | **** |

*p < 0.5, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p<0.0001

The relationship between these two variables and our input variable (“Early video usage”) is further illustrated in Figures 8 and 9. Red points in these figures indicate students who dropped the course. Note that in one case, a student indicated they were dropping the course, but then completed all work and earned a certificate. Similar to Figures 6 and 7, we also find that as the early video chat usage increases, the likelihood of earning higher grades and a certificate of completion also increases.

Summary, Discussion, and Conclusions

Summary

The results of the experiment may be summarized as follows:

- Each additional Riff Video Chat made during the first four weeks of the course predicts a doubling of the odds that the student will receive a certificate of course completion. (Fig. 9)

- Each additional Riff Video Chat made during the first four weeks of the course predicts an increase in the odds of receiving a high grade by 79%. (Fig. 8)

- Most benefits are accrued after participating in the first four to five video chats. Students who participated in more than four calls (an average of one per week) received final grades 80% higher than those who did not and were twice as likely to earn a certificate. (Tables 3–4 and Fig. 8–9)

- We find significantly stronger evidence, as reported in Tables 1–4 and Figures 6–9, of measured metrics linked to user performance, than those reported in the literature by Kim et al. (2008).

Discussion and Conclusions

In our analysis of experiment results, for the first group that completed the entire course, we found strong correlations between the time (in minutes) spent using video to communicate with peers, and every outcome of interest as shown in Table 1. Particularly strong correlations were found between students’ final grades and attainment of course certificates, which has significant commercial implications. Historically, open online courses have had very low completion rates around 5% (Lederman 2019); hence the use of novel tools within online courses can increase engagement, raise the rates of persistence, and improve outcomes. Because this is an observational design, these results do not establish a causal relationship between usage of the Riff Platform and these outcomes, but they suggest that such a relationship may exist. We found that the relationship between video usage and both of our response variables (grades and course completion) was well fit by a logistic curve, as shown in Table 2 and Figure 7. The upward pattern observed in Figures 6–7 simply indicates that the participants are more likely to achieve higher grades and earn a certificate of completion if they more frequently use Riff Video chat.

The reported odds ratios as extracted (reported in Table 2) from the coefficients of the logistic regression model fit suggest results that are statistically significant. The reported values correspond to increases in the odds of a student receiving higher grades by a factor of 23% for each additional hour spent using Riff Video chat and in the odds of passing the course by 35%. The analysis suggests that potential improvements in outcomes are realized with a total exposure of no more than approximately 15 hours over the course.

With the second group of students who remained enrolled during at least the first quarter of the course, the results summarized in Tables 3 and 4 demonstrate that early usage of Riff Platform has an even stronger relationship to the outcomes of interest than usage over the course as a whole. Particularly notable is the effect size for each additional hour of exposure to Riff Video during the first half of the course, which is associated with a doubling of the odds that the student completes the course and earns a certificate. Although this is an observational experiment, again, it suggests that the Riff Platform may be having a significant impact on students’ course completion rates and participation. Similar to Figures 6 and 7, we also observe an upward pattern in Figures 8 and 9, which indicates that this second group of students are also more likely to achieve higher grades in the course and earn a certificate of completion if they more frequently use video. We further note that the high positive correlation values relating measured metrics to user performance in the course are significantly better than those reported in the literature by Kim et al. (2008).

These results suggest that the platform and its nudging mechanisms ultimately benefit student learning as assessed via several exercises completed by the students. The high correlations described above suggest that there is a statistically significant difference in student performance when nudging features such as the MM are used versus not. We also contend that the Riff Platform helps students with self and situational awareness, as it presents the student with live as well as post-session information about their individual and group performance. This helps students adjust themselves in terms of balancing active contribution versus listening to others, and their level of engagement, via the real time feedback loop, when the course requires engagement to meet the learning goals.

These experiments and the corresponding results, though they signal strong correlations between the usage of Riff Platform and all measured output variables, are not without limitations. The results are based only on this set of experiments with this cohort of students in a single course. One could repeat these experiments in a variety of settings (using different cohorts, different countries, and different learning environments and tasks) to see if the results can be generalized. Secondly, we did not have any control variables (such as age, gender, job experience or other variables like prior online learning experience or performance in similar online or offline courses) on the subjects for whom we collected the data. It is possible that students who are successful using the Riff Platform would have been successful anyway because they have prior experience using online learning platforms or they are already high-performing students regardless of the learning environment or tools. Or some students may afford extra time outside the class to review and digest the material, explore additional resources and/or complete additional exercises while others may not. These effects should definitely be included in a more detailed future experimental study. This line of research would highly benefit from an A/B testing approach (e.g., using randomized controlled trials) where one would control for various factors. This requires a different learning environment to be set up where participants are not disadvantaged due to the parameters of the experiment in a legitimate online course where they expect to be provided with equal opportunities for learning.

Another limitation is the fact that the platform only keeps track of audio signals, not the actual content of what is spoken, and it classifies them into three categories as influences, interruptions or affirmations. It is possible that these classifications may not always be accurate, despite the rules we apply, due to backchannel noise. Future work could refine current techniques for identifying the three conversation events with additional hand-labeling, which could then be used to confirm the validity of the rules currently used in the platform.

To capture content being exchanged by participants, there is further opportunity to process spoken words using Natural Language Processing libraries and collect information on the scope and “quality” of the content (e.g., new topics or ideas introduced; sentiment of the words used). The platform could then reflect not only on the frequency or duration of one’s verbal participation, but also its quality.

One may also be concerned about the cost of using such a platform or integrating it with an existing learning management system (LMS). We note that because the platform readily comes as a complete platform solution, there is no additional cost of integrating it with existing LMS. Users simply login and use the features of the platform as needed. Some non-financial “costs” may exist, but they are limited to time and effort needed for training on how to use the system and understand its features such as the MM and Riff Metrics. We believe these costs are quite reasonable as the user interface has been designed with usability in mind.

Finally, though this experiment was within a course for adults interested in expanding their understanding of AI, the participants came from a variety of backgrounds including undergraduate and graduate students, early and mid-career professionals, and government employees. We see potential for this technology to address engagement in virtual settings for any type of collaborative work and any age group. (In all cases, it is important for people meeting in small groups to have an appropriate motivation for collaborating, such as brainstorming or problem solving.)

Even with the limitations noted, our results are a solid first step towards showing that online learning platforms with the right user-facing components providing relevant and prompt feedback to participants are indeed likely to be effective in enhancing the learning experience. This is important especially in the wake of growing demand for online learning platforms due to the COVID-19 pandemic. We believe tools like the Riff Platform and the Meeting Mediator will play an increasingly important role in educational and professional settings where online platforms foster more and more interactions.