“City of Lit”: Collaborative Research in Literature and New Media

Bridget Draxler, Monmouth College

Haowei Hsieh, The University of Iowa

Nikki Dudley, The University of Iowa

Jon Winet, The University of Iowa

The University of Iowa UNESCO City of Literature (UCOL) Mobile Application Development Team1

Abstract

The University of Iowa UNESCO City of Literature (UCOL) project brings together community partners, faculty, and students at The University of Iowa to research, gather, record, and produce multimedia texts about local writers. The team launched its first-phase product in Fall 2010, “City of Lit,” an app for Apple mobile devices. This article describes an experimental course in the university’s general education literature program that involved undergraduate students in the app’s content creation. In addition, it presents initial data for the project’s pedagogical impact based on student surveys, which suggests that the team-based learning project positively impacted students’ perceived learning and motivation.

Introduction

Home of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and designated in 2008 as the only United Nations (UNESCO) “City of Literature” in the Americas, Iowa City has a long and proud history as a community of writers. The University of Iowa’s writing programs have graduated thousands of writers and attracted literary luminaries to Iowa City for seventy years. The city itself contains a wealth of information, both published and archival, on many of its writers.

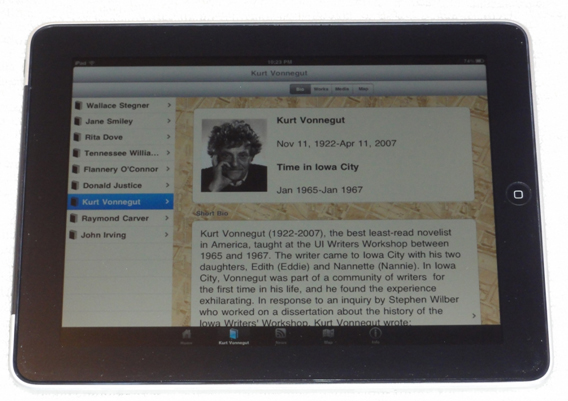

The University of Iowa UNESCO City of Literature mobile application development team (UCOL) project brings together faculty and students at The University of Iowa to research, gather, record, and produce multimedia texts about local writers. Our research team includes faculty and students from the Intermedia Program in the School of Art and Art History, the School of Library and Information Science, the Computer Science and English departments, and the Virtual Writing University staff.2 In Fall 2010 the team launched its first-phase product, “City of Lit,” an app for Apple mobile devices (figure 1).3 The project creates a new media archive of Iowa City’s literary history and includes undergraduate students in the research process alongside experienced scholars.

Figure 1: The “City of Lit” mobile app running on the Apple iPad.

This paper reports our experience from a pilot study in which undergraduate students learned to conduct scholarly research and create content for the digital collection. Students worked collectively to produce multimedia hypertext documents for the app that include text, photos, annotated maps, audio and video. The project encourages interdisciplinary, collaborative undergraduate research, while recognizing the unique potential of mobile devices to make interactive scholarship accessible to the public.

Our paper is organized in three parts. First, we will discuss the UCOL project as a whole, contextualizing student contributions within a larger community-based research project at The University of Iowa by providing information about the app’s background, development, and features. Second, we will describe undergraduate involvement in content creation within an experimental course in the university’s general education literature program. We will outline the assignment and discuss pedagogical changes between the first, second, and third iterations of the course. Finally, we will present initial data for the project’s pedagogical impact based on student surveys.

The UCOL project provides an opportunity for undergraduate students to publish new media research on a mobile app, and our research suggests that the project positively impacts students’ perceived learning and motivation. In addition, our use of mobile technologies promotes engagement by a wider public and capitalizes on the interactive capability of location-aware technologies.

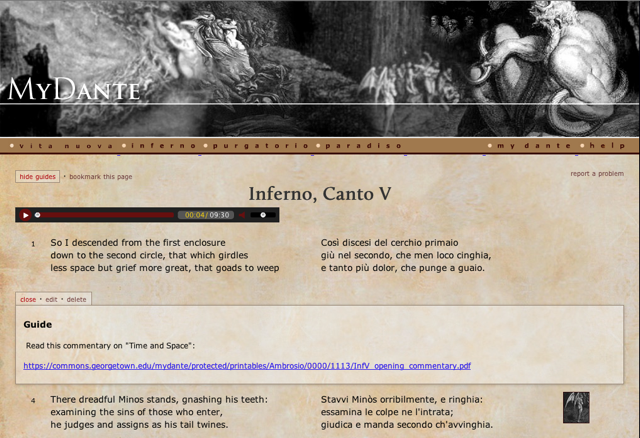

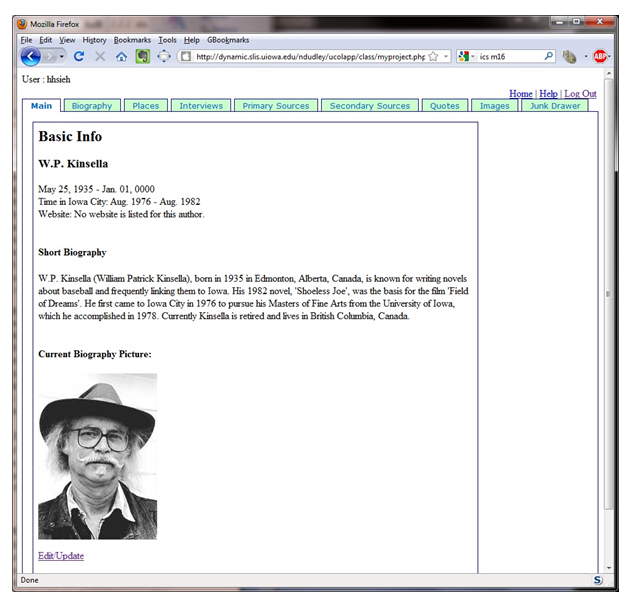

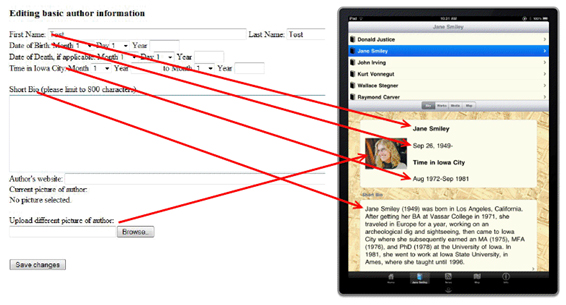

The “City of Lit” Mobile App

The “City of Lit” system framework consists of a web-based content editing interface, a development database containing in-progress content, a collection of websites that host full-length original content for a selection of authors, and a production database of public content which serves the mobile app. Authorized scholars and researchers can contribute to the collection from remote locations, using the web interface (figure 2) to enter data into the development database. Within the interface, students can view each other’s work-in-progress alongside the content of contributing scholars. Students and scholars, then, operate on equal and open terms within the project. Once material is approved by the editorial staff, data is reviewed and copied to the production database.

Figure 2: Web-based interface for data-entry and update.

When the app is started, the user is presented with a “quote of the day,” immediately following the UNESCO City of Literature splash screen. A tap on the screen takes users to a list of available authors and other options for navigating the app. Using the device’s location service, the app identifies Iowa City area locations of interest (figure 3).

Figure 3: A map of Iowa City with locations marked with pins.

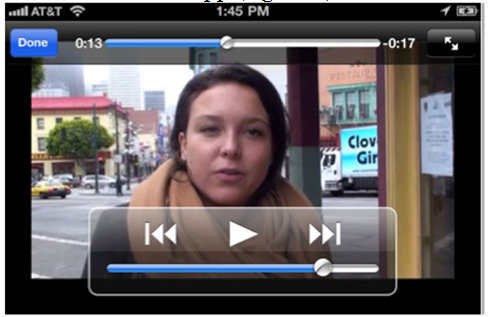

Examples of geo-tagged events include locations of local readings, former dwellings of resident writers, and real or fictional Iowa City locations referenced in literature. This information can be used to take a literary stroll through Iowa City or to visit sites relevant to a specific author. Multi-media elements are central to the app (figure 4).

Figure 4: “City of Lit” can stream video and audio.

Users can access a constantly growing collection of audio and video recordings of readings and interviews, along with photography and graphics related to the authors. Other constantly updated features of the app include News and Events, information dynamically fed from the Virtual Writing University website.

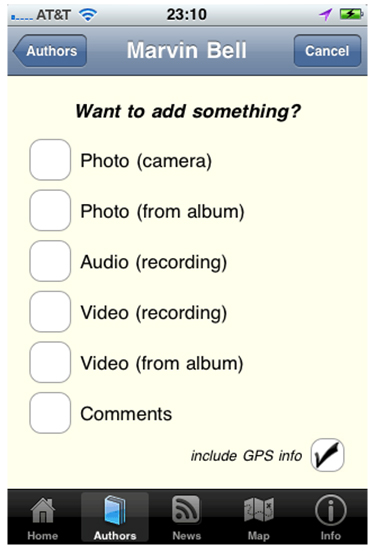

We have developed the mobile application for the iOS platform, including iPhone, iPod touch, and iPad. The projected audience for our app will increase as we expand support for additional platforms through the launch of a dedicated Android version of the app4 and a web application designed for both mobile and full-screen devices.5 In the next phase of app and programming development, users will be able to contribute personal text, photo, video and audio commentaries through a file uploader function (figure 5).

Figure 5: A screen shot of user file uploader.

Dubbed “Citizen Scholarship,” this feature adds a new layer of interactivity to the app as users become content contributors. Our goal is to make the app itself (like the student contribution) as interactive and participatory as possible.

Related Works

The UCOL project builds on the work of a wider community of innovators in technology and pedagogy. Scholars have shown that new media affords new possibilities for interactive pedagogy and cultural citizenship.6 In recent years, the dynamic nature of Web 2.0 has encouraged a more participatory engagement with technology. Blogs, podcasts, wikis, interactive learning exhibits, and other forms of web-based student-publishing media have transformed the student learning process, making it more interactive, more authentic, and more impactful.7 And unlike clickers, games, or smart boards, student-publishing media engage students in the production of new knowledge, by inviting students to create multimedia representations of their learning. In their best form, these digital systems create a role-reversal between teachers and students, helping students to become writers, editors, and commentators8 and to experience increased agency within a democratic learning space.9

By focusing on problem-based networked learning, interactive technology can be integrated into the political science classroom10 as easily as the dance studio.11 Scholarship suggests that using social networking media in the classroom not only facilitates interactive pedagogy but also more effectively fits the learning styles of students today.12 Gary Beauchamp and Steve Kennewell explore the role of interactive technology within interactive learning, pointing to ways that such pedagogy places more responsibility on the learner.13 For many practitioners of technology-based pedagogy, one goal of such projects is to promote more creative and collaborative student-driven learning.

Recently, scholars have begun to explore specific ways that mobile technology can serve as a platform for this participatory, problem-based pedagogy. David J. Radosevich and Patricia Kahn have showed the impact of using tablet technology and recording software to increase student engagement in their learning process.14 Thomas Cochrane and Roger Bateman have published a model and rubric for “m-learning” (mobile learning projects), which emphasizes the use of interactive technology projects for students in online courses who do not identify themselves as tech-savvy.15 In a study of mobile-based games, James M. Mathews discusses a Neighborhood Game Design Project that creates a virtual reality simulation.16 However, scholarship on mobile technology has not yet considered student-publication on mobile devices, in which students create rather than simply use mobile apps. In addition to multimedia features including text, images, audio, and video, mobile apps can also employ GPS technology to create geo-centric media. The UCOL team uses mobile technology to create an interactive and local collection.17

Building on research surrounding Web 2.0 practices, social networks, and the ascendancy of mobile technology, our project provides a model for mobile-based student publishing. In addition, we have conducted survey-based research on the impact of mobile app creation on students’ perceived learning. Our research suggests that the structure of the UCOL project motivated students to work harder and learn more than in a traditional literature course.

Undergraduate Content Creation for “City of Lit”

During Fall 2010, English doctoral candidate Bridget Draxler incorporated “City of Lit” research into her undergraduate “Interpretation of Literature” course. Her students conducted research and created multimedia content on local authors. UCOL team members worked closely with undergraduate students in the class, providing technical support and training in multimedia authoring.

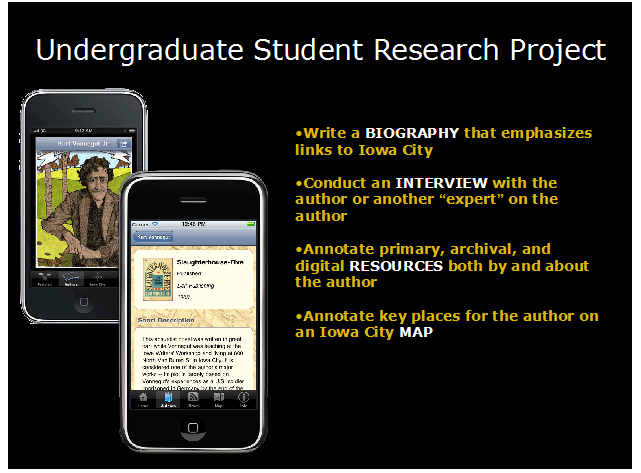

For the project, each student chose one Iowa City author to research. The six-week assignment directed students to: interview their author or a resident expert;18 conduct research in the University Archives of the University of Iowa Libraries Special Collections; identify key locations for their author around town; annotate a series of primary and secondary resources; and write a comprehensive biography that emphasizes their author’s time in Iowa City (figure 6). Students uploaded their research to an online interface (figure 7); their research was vetted by a professional editor, who provided revision before its final publication.19 By focusing on the author’s time in Iowa City, students helped to create a unique and locally-relevant collection.

Figure 6: Summary of undergraduate research project

Figure 7: Content is translated from an online interface (left) to the mobile app (right).

Based on the success of this initial undergraduate class project, Draxler and UCOL expanded the project into a semester-long course offering.20 The new course included a number of changes:

- We redesigned the project for a full 16-week class, up from the original 6 weeks. This change allowed students more time to learn archival research methods, new media tools, interviewing strategies, etc;

- Students completed the assignment in groups of two or three, working collaboratively, improving the quality of student research and writing and the students’ learning experience.

- We offered two sections of the course during Spring 2011, doubling the number of participating students from 20 to 38, and creating a wider pool for assessment;

- Students shared their work in a public forum through Prezi and pecha-kucha21 presentations at the City of Lit Iowa Authors Event.22 Local writers participated in the event by giving readings of their work.23

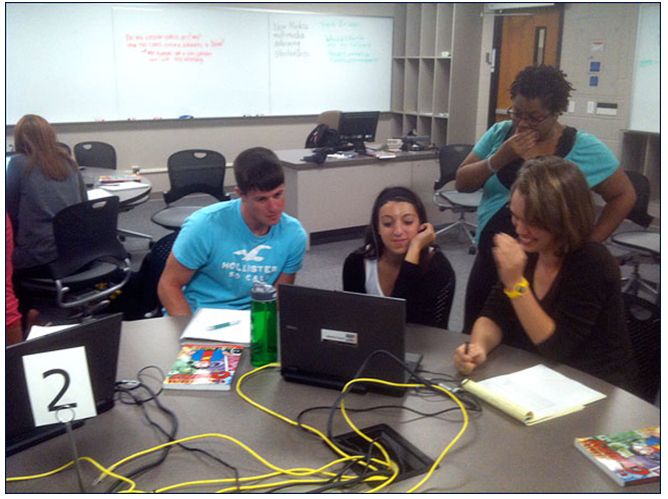

In Fall 2011, the course underwent further change, offered for the first time as an upper-level elective, cross-listed in the departments of English and Art. As an elective rather than a general education course, the class attracted students who already had an interest in new media research. Team-taught by Professor Jon Winet and graduate student Raquel Baker, the course also took advantage of the University of Iowa’s new TILE classrooms (figure 8), which facilitate technology-based, peer-to-peer learning through round tables, wall-to-wall white boards, and networked monitors and screens (figure 9). We anticipate that this cross-listed course will be offered annually in the future, and as some project leaders have taken positions in new institutions, we hope that it will provide a template for similar courses in other college communities.

Figure 8: TILE classroom. Photograph from The University of Iowa website.

Figure 9: Students with instructor Raquel Baker in TILE classroom, Fall 2011

Impact of “City of Lit” on Student Learning

Student reflections and evaluations during Fall 2010 and Spring 2011, along with a formal survey designed by the UCOL team in Spring 2011, identified strengths and weaknesses of our project. Student feedback suggests that the integration of literary research and analysis, new media and technology, and local community engagement provided valuable learning outcomes. As one student in the initial pilot course commented,

By starting this project, I found new ways of conducting research. These include things such as interviews with people who had a direct tie to the author, and also going to the University of Iowa archives to obtain new research. The project is very interesting because it focuses on a broad range of writing, such as the biography and the bibliography, and it showed me how to conduct a formal interview, along with using new types of technology.

In Spring 2011, we conducted a formal survey with the 38 participating students. The survey collected information concerning their multimedia skills before and after the class, their opinions toward the new class style and public scholarship, their self-evaluation of personal improvement in variety of areas, and their overall impression of the class. We also conducted a targeted evaluation on certain interface and usability issues.24 Data from the formal survey notes a high perceived impact on student learning.

According to our survey, the structure of the research assignment provided students enough room for flexibility and creativity (73.6% agreement), gave students ideas in directing and presenting their research (76.3% agreement), and taught students skills that they think are useful (71.0% agreement).

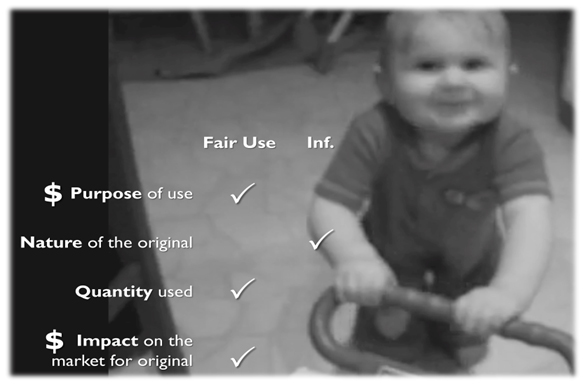

Students overwhelmingly agreed that they learned more by doing this type of assignment than by writing a traditional research paper (figure 10).

Figure 10: On questions “I learned more by doing this type of assignment than a traditional research paper” and “I prefer this kind of assignment to a traditional research paper”

Student surveys recommended that we provide future students with online video tutorials for in-class demonstrations, to make the rather technical process of creating multimedia content easier.

In addition to identifying development in digital literacies, the students also noted perceived improvement in personal growth, academic growth, civic engagement, research methods, writing skills, and speaking skills.

Students showed the most personal development in the following areas: persistence, personal responsibility in learning, problem solving, and understanding of local culture. Many of these qualities support student-driven learning, suggesting that interactive technology and student publication increases students’ personal responsibility and ownership in their education.

In addition, students self-identified as improving most in the following skills: archival research methods, primary research methods, bibliographic skills, clarity of writing, and abilities to communicate with peers. In addition to learning skills in new media, the students felt that they made significant improvements in more traditional skills (like literary research and citation) required for the general education course.

Students showed improvements but to a lesser degree in the following areas: online research methods, patience, and interest in literature.

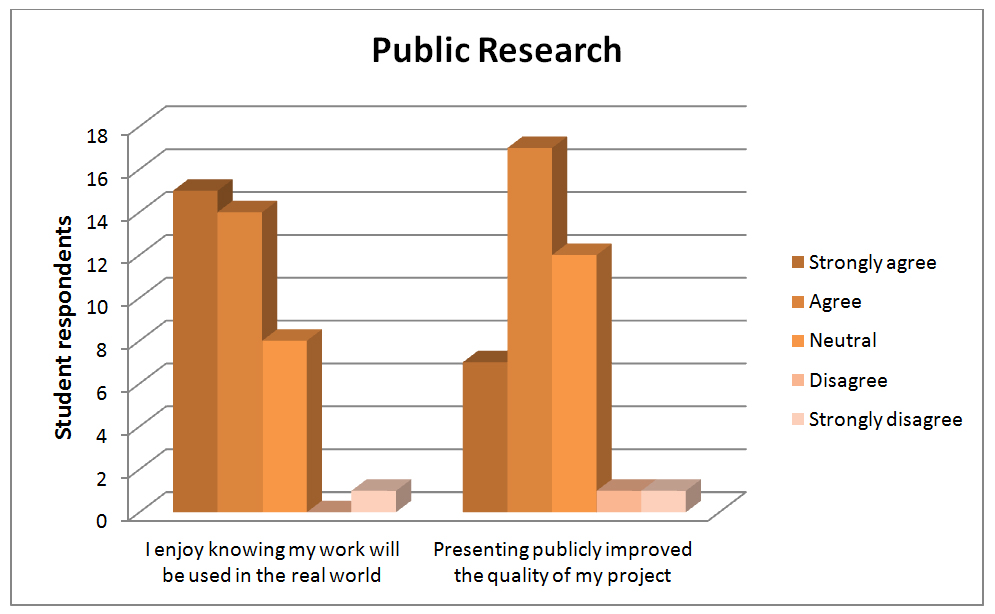

Figure 11: On questions “I enjoyed knowing my work will be published, read by the public, and used in the real world”, and “Did presenting your work to a public audience improve the quality of your project?”

Students found the public presentation to be a useful capstone, and they enjoyed meeting a real audience of their virtual publication. One student wrote, “It gave me confidence and pride in the work we’ve done.” Another student commented, “I thought the public presentation made the whole project feel more official.” Another student noted, “I’ve never presented to a group other than my class so it made it seem more professional.” To another, “It was exciting because it solidified the idea that we’re making something for the public.”

The public component of students’ research successfully created a sense of authenticity for their work, and students “enjoyed knowing their work would be published, read by the public, and used in the real world.” Students also agreed that presenting their work to a public audience, at the Iowa Authors Event, improved the quality of their project (figure 11).25

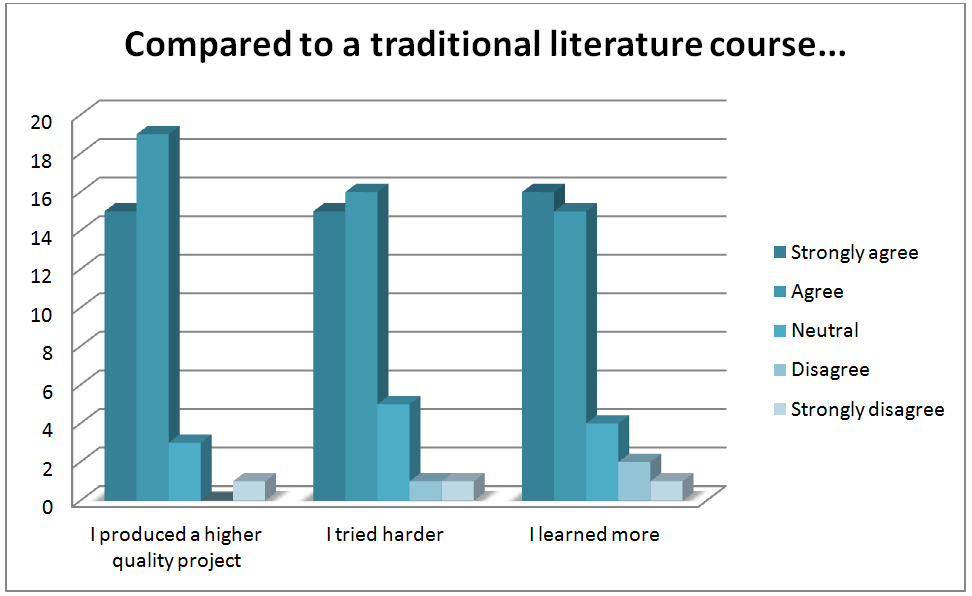

Students said that they produced a higher-quality project than they would have done in a traditional literature classroom, and they tried harder on this project than they would have in a traditional literature classroom. And finally, students felt that they learned more in this class than they would have in a traditional literature classroom (figure 12).

Figure 12: On questions “I produced a higher-quality project than I would have in a traditional literature classroom”, “I tried harder on this project than I would have in a traditional literature classroom”, and “I learned more in this class than I would have in traditional literature classroom”

Overall, our research shows that this project positively impacted students’ perceived learning and motivation. Their reflections also suggest that, in addition to improved skills and motivation, the project was also a transformative experience for many students. “[I am] very glad I took this class,” said one student, “because I can use stuff I learned in the real world.” Through their collaborative multimedia research and publication, students felt more engaged and invested in their community, but also in their own learning.The UCOL project serves as an exemplar at The University of Iowa and in the field of digital humanities and new media, illustrating how traditional scholars can participate in engaged digital humanities research, facilitating intercollegiate collaboration at the highest levels of creative research and practice.

Bibliography

Al-Khatib, Hayat. “How Has Pedagogy Changed in a Digital Age? ICT Supported Learning: Dialogic Forums in Project Work.” European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, no. 2 (2009). http://www.eurodl.org/?p=current&rticle=374&article=382. ISSN 1027-5207.

Baird, Derek E., and Mercedes Fisher. “Neomillennial User Experience Design Strategies: Utilizing Social Networking Media to Support‘ Always on’ Learning Styles.” Journal of Educational Technology Systems 34, no. 1 (2005): 5–32. doi:10.2190/6WMW-47L0-M81Q-12G1.

Beauchamp, Gary, and Steve Kennewell. “Interactivity in the Classroom and Its Impact on Learning.” Computers & Education 54, no. 3 (April 2010): 759-766. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2009.09.033.

Bullock, Shawn Michael. “Teaching 2.0: (re)learning to Teach Online.” Interactive Technology and Smart Education 8, no. 2 (June 14, 2011): 94-105. doi:10.1108/17415651111141812.

Cochrane, Thomas, and Roger Bateman. “Smartphones Give You Wings: Pedagogical Affordances of Mobile Web 2.0.” Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 26, no. 1 (2010): 1-14. ISSN 1449-3098.

Damron, Danny, and Jonathan Mott. “Creating an Interactive Classroom: Enhancing Student Engagement and Learning in Political Science Courses.” Journal of Political Science Education 1, no. 3 (2005): 367-383. doi:10.1080/15512160500261228.

Davidson, Cathy N, and David Theo Goldberg. The Future of Thinking: Learning Institutions in a Digital Age. The MIT Press, 2010. ISBN 9780262513746.

Doughty, Sally, Kerry Francksen, Michael Huxley, and Martin Leach. “Technological Enhancements in the Teaching and Learning of Reflective and Creative Practice in Dance.” Research in Dance Education 9, no. 2 (2008): 129-146. doi:10.1080/14647890802088041.

Joe Fassler at Iowa Author’s Event, 2011. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OvJMW-0wxYA&feature=youtube_gdata_player.

Mannion, Lance. “Interview with Lance Mannion1.” Interview by Jessica McCarthy and Wei Ren. Online posting, March 31, 2011. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-5A-uwcJk04.

———. “Interview with Lance Mannion2.” Interview by Jessica McCarthy and Wei Ren. Online posting, April 1, 2011. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ki8pZtzwDzg&feature=youtube_gdata_player.

Marquis Childs by Ryan & Heather, 2011. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3xo3QpCvhh4&feature=youtube_gdata_player.

Mathews, James M. “Using a Studio-based Pedagogy to Engage Students in the Design of Mobile-based Media.” English Teaching: Practice and Critique 9, no. 1 (2010): 87–102. ISSN 1175-8708.

Radosevich, David J., and Patricia Kahn. “Using Tablet Technology and Recording Software to Enhance Pedagogy.” Innovate Journal of Online Education 2, no. 6 (2006): 7. ISSN 1552-3233.

Schaffhauser, Dian. “Which Came First–The Technology or the Pedagogy?” THE Journal 36, no. 8 (2009): 6. ISSN 0192-592X.

Yeh, Hui-Chin, and Yu-Fen Yang. “Prospective Teachers’ Insights Towards Scaffolding Students’ Writing Processes Through Teacher–student Role Reversal in an Online System.” Educational Technology Research and Development 59, no. 3 (October 7, 2010): 351-368. doi:10.1007/s11423-010-9170-5.

Zhao, Ruijie. “Weaving Web 2.0 and the Writing Process with Feminist Pedagogy”. Thesis, Bowling Green State University, 2010. http://etd.ohiolink.edu/view.cgi?acc_num=bgsu1276676479.

About the Authors

Bridget Draxler is a first-year assistant professor and director of an interdisciplinary writing program at Monmouth College, a liberal arts college in Monmouth, IL. Her current role at the college allows her to support student speaking and writing skills by developing public digital humanities initiatives within the college’s core curriculum. As a graduate student at the University of Iowa, she developed a course in Iowa literature as part of The University of Iowa UCOL Mobile Application Development Team.

Haowei Hsieh is Assistant Professor in the School of Library and Information Science at The University of Iowa. He leads the database design group for The University of Iowa UNESCO City of Literature Mobile Application Development Team. He works closely with the Graduate Informatics program at the University of Iowa for his interdisciplinary work that studies the interaction between people, information, and machines.

Nikki Dudley is a recent graduate of the University of Iowa School of Library and Information Sciences and current researcher in the Digital Studio for Public Humanities. Her recent work has included database development for The University of Iowa UNESCO City of Literature Mobile Application Development Team. Among her research interests are data visualization and designing web interfaces for digital collection content creation.

Jon Winet is a New Media artist and researcher. In August 2011 he was appointed director of The University of Iowa Digital Studio for the Public Humanities (DSPH). He also directs the University of Iowa UNESCO City of Literature Mobile Application Development Team and the Experimental Wing of the University of Iowa Virtual Writing University. He is an Associate Professor of Intermedia in the University of Iowa’s School of Art and Art History, as well as a member of the faculty of International Programs.

Additional UCOL members include James Cremer, Lauren Haldeman, Dat Nguyen, Peter Likarish, and Raquel Baker.

Notes

- Additional UCOL members include James Cremer, Lauren Haldeman, Dat Nguyen, Peter Likarish, and Raquel Baker. ↩

- The Virtual Writing University (http://www.writinguniversity.org/) is an initiative that brings together The University of Iowa’s many writing programs. In addition to campus partners, the UCOL team also works closely with the Iowa City UNESCO City of Literature organization (http://cityofliteratureusa.org/). ↩

- At the time of our original launch, iOS was the market leader for mobile apps. With the growth of the Android market, we are developing an Android version of the app. The iOS app can be downloaded from http://itunes.apple.com/us/app/the-iowa-city-unesco-city/id396516495?mt=8. ↩

- Projected launch: spring 2012 ↩

- Currently in beta: http://dsph.uiowa.edu/vwu/ucol/mobile/ ↩

- In “Everyday Creativity as Civic Engagement: A Cultural Citizenship View of New Media,” Burgess, Foth, and Klaebe argue that new media opens possibilities for “community-building potential.” 2006, 1, http://eprints.qut.edu.au/5056/. They cite Joke Hermes’ definition of cultural citizenship: “the process of bonding and community building, and reflection on that bonding, that is implied in partaking of the text-related practices of reading, consuming, celebrating and criticizing offered in the realm of (popular) culture” (quoted in Burgess, Foth & Klaebe, 4). Although Hermes’ definition does not explicitly consider digital technology, the authors suggest that new media will be a critical tool in the future of cultural citizenship both inside and outside the classroom. ↩

- Derek E. Baird and Mercedes Fisher, “Neomillennial User Experience Design Strategies: Utilizing Social Networking Media to Support‘ Always on’ Learning Styles,” Journal of Educational Technology Systems 34, no. 1 (2005): 5–32. ↩

- Hui-Chin Yeh and Yu-Fen Yang, “Prospective Teachers’ Insights Towards Scaffolding Students’ Writing Processes Through Teacher–student Role Reversal in an Online System,” Educational Technology Research and Development 59, no. 3 (October 7, 2010): 351-368. ↩

- Ruijie Zhao, “Weaving Web 2.0 and the Writing Process with Feminist Pedagogy” (thesis, Bowling Green State University, 2010), http://etd.ohiolink.edu/view.cgi?acc_num=bgsu1276676479. Even technophiles acknowledge skepticism that technology is valuable in the classroom for its own sake; critics emphasize the necessity of demonstrating student learning beyond new digital literacies. See Dian Schaffhauser, “Which Came First–The Technology or the Pedagogy?,” THE Journal 36, no. 8 (2009): 6; Shawn Michael Bullock, “Teaching 2.0: (re)learning to Teach Online,” Interactive Technology and Smart Education 8, no. 2 (June 14, 2011): 94-105; Hayat Al-Khatib, “How Has Pedagogy Changed in a Digital Age? ICT Supported Learning: Dialogic Forums in Project Work,” European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, no. 2 (2009), http://www.eurodl.org/?p=current&rticle=374&article=382. ↩

- Danny Damron and Jonathan Mott, “Creating an Interactive Classroom: Enhancing Student Engagement and Learning in Political Science Courses,” Journal of Political Science Education 1, no. 3 (2005): 367-383. ↩

- Sally Doughty et al., “Technological Enhancements in the Teaching and Learning of Reflective and Creative Practice in Dance,” Research in Dance Education 9, no. 2 (2008): 129-146. ↩

- Baird and Fisher, “Neomillennial User Experience Design Strategies.” ↩

- Gary Beauchamp and Steve Kennewell, “Interactivity in the Classroom and Its Impact on Learning,” Computers & Education 54, no. 3 (April 2010): 759-766. ↩

- David J. Radosevich and Patricia Kahn, “Using Tablet Technology and Recording Software to Enhance Pedagogy,” Innovate Journal of Online Education 2, no. 6 (2006): 7. ↩

- Thomas Cochrane and Roger Bateman, “Smartphones Give You Wings: Pedagogical Affordances of Mobile Web 2.0,” Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 26, no. 1 (2010): 1-14. ↩

- James M. Mathews, “Using a Studio-based Pedagogy to Engage Students in the Design of Mobile-based Media,” English Teaching: Practice and Critique 9, no. 1 (2010): 87–102. ↩

- The distinctive features of the mobile app, then, inform not only the structure but also the content of the collection. ↩

- For an example of a student interview, see Lance Mannion, “Interview with Lance Mannion1,” interview by Jessica McCarthy and Wei Ren, online posting, March 31, 2011, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-5A-uwcJk04; Lance Mannion, “Interview with Lance Mannion2,” interview by Jessica McCarthy and Wei Ren, online posting, April 1, 2011, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ki8pZtzwDzg&feature=youtube_gdata_player. ↩

- Student content is still currently being edited, but much of this content is already included in the current version of the “City of Lit” app. ↩

- You can view the course syllabus for Spring 2011, the first iteration of “City of Lit” as a semester-length project, at the following link https://docs.google.com/document/d/1uxtXjgB4OiSlogb7Px_zVu6jASpfA9HRsA6OHnyQPEQ/edit. ↩

- Pecha-kucha is an experimental PowerPoint presentation form. Pecha-kuchas, six minutes and forty seconds in length, consist of twenty slides, each shown for twenty seconds. ↩

- http://cityofliteratureusa.org/node/131. For an example of a student presentation at the Iowa Authors Event, see Marquis Childs by Ryan & Heather, 2011, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3xo3QpCvhh4&feature=youtube_gdata_player. ↩

- For an example of an local author reading at the Iowa Authors Event, see Joe Fassler at Iowa Author’s Event, 2011, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OvJMW-0wxYA&feature=youtube_gdata_player. ↩

- The survey was conducted by the research team and not by the instructor, with IRB approval. The instructor received results after all information was collected and grades were finalized. ↩

- These presentations allowed students an opportunity to describe the process, rather than the product, of their research, reflecting on what they learned and how they learned it. ↩