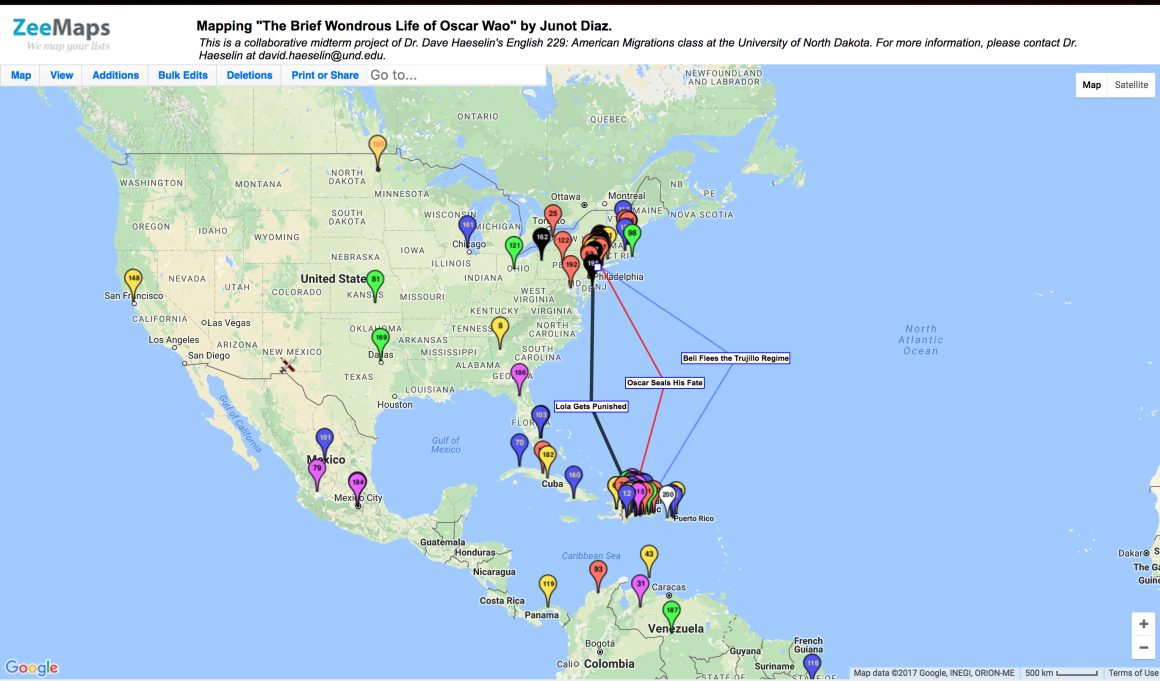

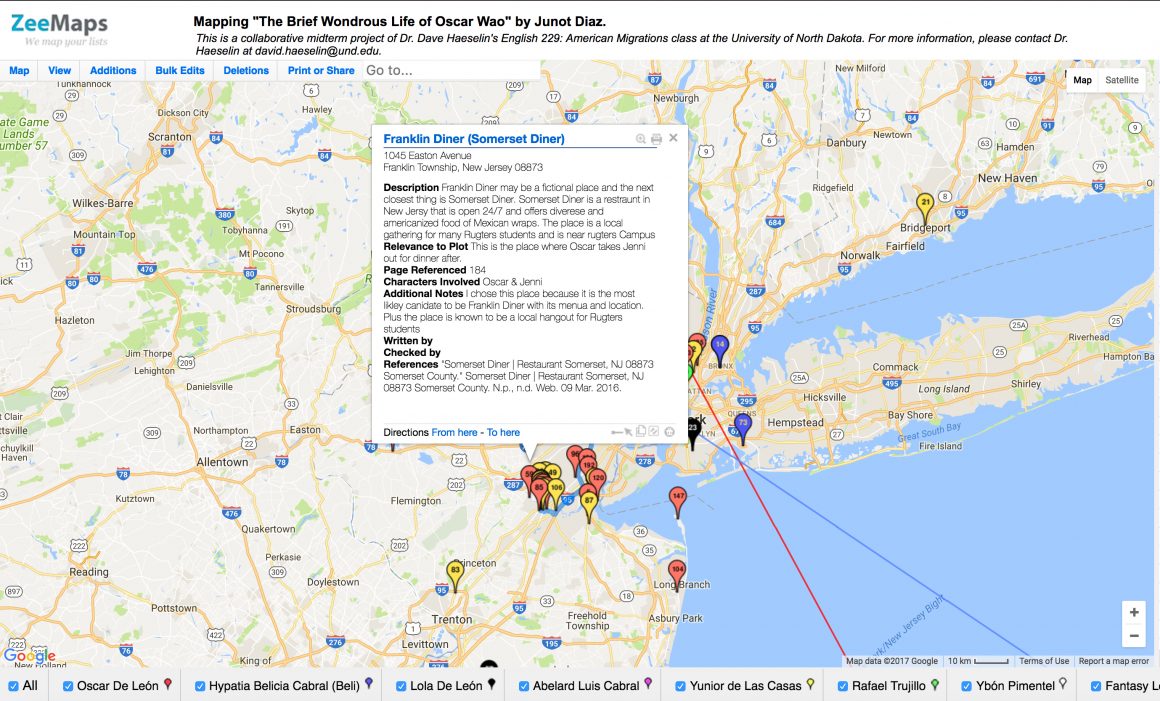

Introduction: Course Overview and Objectives

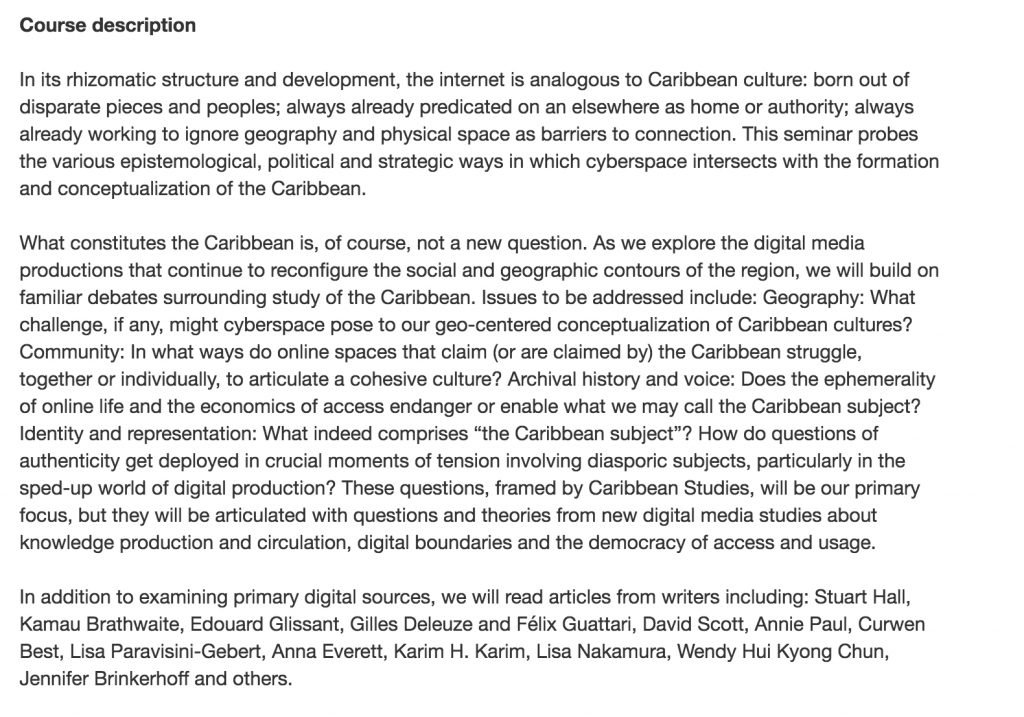

I teach a first-year, multimodal composition course at the Georgia Institute of Technology themed around interactions between animals and technology. I titled the course “Technocritters, or Animals and/as Technology.” Broadly, the course aims to develop students’ skills in multimodal communication (including written, visual, oral, nonverbal, and electronic communication) through an emphasis on process and rhetoric. As the second course in Georgia Tech’s two-semester first-year composition sequence, students should arrive in my course having been introduced to basic rhetorical concepts and strategies for effective communication. One of the “animals and/as technology” theme-related areas we study is the impact of new media on representations of animals. We ask questions such as: When and why does new media represent animals? How do the social media interfaces we use to access and share images of animals shape our understanding of them as food, pets, or pests?

For a STEM-focused institution like Georgia Tech, many of the first-year students I encounter plan to study in fields that will require that they utilize existing technologies and engineer new interactive computer systems for both specialized and public audiences. Consequentially, a course themed partially around a rhetorical analysis of computer-mediated communication helps increase engagement in a course students widely regard as “required” but not desired. Further, digital literacy skills are increasingly essential for all first-year college students, particularly given the near-ubiquity of interactive technologies in students’ academic, workplace, and recreational lives. Even writing programs and composition courses that prioritize traditional genres of academic writing must take notice of the rapidly growing rhetorical influence of new media on students learning to write, read, and think in the twenty-first century.

Digital Literacy… with Animals

At the beginning of each section of this course, I take an informal survey to learn a little about students’ personal histories, including their personal experiences with animals. As a group, we establish students’ prior knowledge about animals as a baseline for their exploration of animals in new media. Such a baseline enables us to raise questions such as: To what extent do animals in new media challenge or reinforce my previous assumptions about how animals look, move, think, and feel? How can and should humans interact with them? What are animals “for”? Almost all students enter my courses having had experiences with animals typical for young adults from non-rural areas of America. That is, few have first-hand experience with animals beyond their family dog or cat. Between two and three students may have experience riding horses, hunting deer or small game animals, or tending to farmed animals. Nearly all students have visited at least one zoo or amusement park that displays captive animals. Several students (between 4-5 each semester out of 75) have worked with or are currently working with animals in a laboratory setting: always mice. Finally, very few students—roughly three out of 75 every semester—identify as vegetarian or vegan. Therefore, most students are familiar with animals as products for consumption, even though, by students’ own admission, they do not readily make the association between the sliced meat on their lunch plates and animals.[1]

After students identify their personal history with animals, I prompt them to consider how varied media forms affect their understanding of animals, particularly nonhuman behavior and appearance. Students are quick to admit to consuming new media texts—including memes, Instagram profiles, and videos—as a source of “information” about animals. At the time of this writing, dogs and puppies (or, per the language of doggolingo, “doggos” and “puppers”) enjoy wide popularity across social media platforms. Cats and kittens (including Grumpy Cat, Maru, and the many Lolcat variants)—a variety of companion animal once nearly synonymous with digital image virality—persist in students’ vocabulary. That said, some students go so far as to claim that internet cats are “outdated.” Such recognition on their part—internet trends come and go rapidly—is an important insight: it helps students recognize that patterns of representation—such as the once-ubiquitous new media portrayal of house cats as playful, erratic, and cute—are neither fixed nor inevitable. As Sarah Warren-Riley and Elise Verzosa Hurley suggest, even when it comes to cat memes, “Liking, sharing, or reposting a cute cat meme does result in advocating specific values and ideologies (regardless of whether the individual agrees with those values) and results in something (in this case, the reinforcement of Western values that cats are cute house pets)” (Warren-Riley and Hurley 2017). By asking students to consider the frequency with which certain animal behaviors are visually depicted and shared through new media, I want to encourage them to consider how pervasive but undertheorized texts like cat memes advance ideologically-laden understandings about the subjects those texts represent, such as which nonhuman species should be treated variously as “pets,” “pests,” or “food.”

Developing students’ digital literacy additionally requires that students consider how computer interfaces facilitate and constrain the actions they perform in digital environments. My use of the term “interface” refers to the programs (such as applications and software) and hardware (including a mouse, keyboard, and display screen) that enable interaction between computers and people (rendered through said interaction as “users” or, for video games, as “players”). When it comes to a rhetorical study of new media, students must consider not only the content of new media (the memes themselves), but also the means through which such content is disseminated (interfaces that include but are not limited to those of social media). Because the interfaces of social media make sharing content easy, for example, students are likely to consider the act of “liking,” “retweeting,” or “upvoting” a piece of internet content “mundane and routine” and, by extension, inconsequential (Warren-Riley and Hurley 2017). To challenge the notion that the act of sharing content online is meaningless, we might ask students: what is the relationship between the popularity of animal images on the internet and the ease with which we share those images?

The pervasive tendency for humans to project meaning onto animals’ often inscrutable behaviors and expressions works in tandem with the seeming effortlessness involved in sharing content on social media platforms. Joseph Anderton (2016) advocates for such a contextual assessment of internet memes, writing that the meme’s “ability to pervade privy groups cements non/human animals in facetious material and renders them vacuous figureheads subsidiary to human meanings” (142). That is, the represented animal, rather than the meme itself, is rendered vacuous by the form’s popularity across web platforms. Memed animals become flexible signifiers for a range of human expressions and desires, a flexibility that advances an understanding of animals as a kind of bare material upon which human meanings can be inscribed. Here, the ease of sharing content online encourages the proliferation of texts and genres with highly malleable semiotic potential.

This example of the “Chemistry Cat” meme demonstrates how cultural values and assumptions inform animal memes. For example, the cat’s white fur resembles a white lab coat, her glasses serve as a cultural signifier of intelligence, and her bow tie implies the traditional representation of men as scientists.

Teachers of digital literacy and rhetoric are therefore faced with a two-part challenge. First, students must learn to recognize how new media representations, such as the cat in the cat meme, reinforce variable—that is, both prevailing and niche—cultural values. Second, students must learn to recognize and consider how the interfaces that enable the circulation and popularization of certain representations are themselves built to encourage and facilitate a particular set of user actions. Asking students to consider how interfaces encourage, facilitate, or reward certain user actions and behaviors enables them to perceive interfaces as rhetorical. The range of social media platforms that students interact with every day can serve as a reliable starting place for students to begin this process of recognition. I have found, for example, that students are quick to recognize how social media platforms encourage users’ public affirmation of posted content (via the “like” function on Instagram) as well as the broader sharing of that content (such as “retweets” on Twitter).

Students’ examination of how they interact with computer interfaces should not and cannot end with a consideration of social media, however. Computer interfaces endeavor to conceal their function as rhetorical texts, that is, their own status as persuasive tools that influence user behavior. As Lori Emerson (2014) underscores, “interfaces themselves and therefore their constraints are becoming ever more difficult to perceive” as contemporary technology seduces us with feats that seem at once “wondrous” and magical (x). To be sure, the range of interfaces with which students interact on a daily basis are varied and quickly changing. Many college students own at least one if not multiple personal computers (including laptops, tablets, and smartphones) for both academic and recreational use, and their experience of those interfaces—except, perhaps, when they fail to work seamlessly—are likely to go largely without much or any critical inspection. Teena Carnegie (2009) argues that teachers and students of writing must learn to talk about the often invisible or “natural”-seeming work of interfaces (166). For Carnegie, as interfaces work continually to engage the audience through interaction, they create “higher levels of acceptance in the user,” acceptance that leads to the increased invisibility of the interface itself (171). In consequence, increasingly taken-for-granted interfaces make users more susceptible to persuasion and more likely to “accept the messages contained within the content, to continue to use a particular site, or to perform certain actions” (171-2). To my mind, that interfaces both render themselves invisible and dispose users to accept messages make the study of the rhetorical work of interfaces essential to developing students’ digital literacy.

Why Video Essays?

A video essay project like the one I assign in my multimodal composition courses presents not only an opportunity for students to practice strategies of analysis and argumentation, but also the opportunity to reflect on how software interfaces ask them to behave. Like written essays, video essays should make a clear argument. Additionally, video essay creators must consider how audible and visual registers reinforce, elaborate on, conflict with, or distract viewers from the essay’s argument. Therefore, successful video essays take seriously how the combination of moving images, still images, oral narration, and a revised, written script can work together to facilitate audience comprehension. Moreover, assigning students a video essay project provides one way for them to practice composing in all of the modes of communication.

As a form, video essays are particularly popular as an emergent form of film criticism. Rather than rely on written descriptions or even screenshots of filmic features, film critics increasingly turn to video essays for their ability to present for analysis the complex visual and nonverbal features in films, features that include lighting, shot design, sound, and costume. To show students the wide range of approaches to video essay design that critics take, I offer them writer Conor Bateman’s “The Video Essay as Art: 11 Ways to Make a Video Essay,” a brief, introductory text useful for its discussion of varied video essay forms as the vlog, scene breakdown, and desktop video. Then, to demonstrate how digital media critics have turned to the video essay for the purposes of making arguments supported by visual evidence and gameplay analysis, I refer to Anita Sarkeesian’s series “Tropes vs Women in Video Games” on the website Feminist Frequency.

Thanks to screen-capture software (including free tools such as Open Broadcaster Software), students can record particular moments of interaction between themselves and software interfaces for later use in video essay arguments. After recording, students can review their documented interactions and analyze them. To be clear, the aspect of the video essay project that requires students to record their interactions is, to my mind, essential. The process of recording footage for the video essay and then constructing an argument using that footage asks students to critically assess how software interfaces incline them to behave in particular (and variously circumscribed) ways. The process of recording, reviewing, and analyzing also has the effect of making students more interface-savvy. That is, after recording their actions in one interface, they may become more likely to reflect on how their actions in other systems could undergo similar analysis.

Why Video Games?

Video games as persuasive texts lend themselves well to student analysis of the often hidden rhetorical implications of software interfaces. More explicitly than the social media interfaces mentioned above, video games as software ask players to behave according to a set of rules or constraints in order to advance or “win.” Relevant to the “animals and/as technology” theme of my course, video games present strong arguments for how players should interact with and, by extension, regard the animals they encounter within game worlds. In response, I ask students to explore how players can interact with animals in games as a means to uncover the implicit or explicit arguments video games make about human-animal relationships. For example, students raise questions such as: what forms of interaction between humans and animals does the game afford me, the player? How easy does the game make it for the player to facilitate that interaction? Is the interaction sustained, or brief? What is that animal’s function in relationship to the player and/or to the game’s narrative? Is the player required to kill or otherwise manipulate the animal to proceed with the game? Can the player mount the animal and use it as a form of transportation or to enhance the player-character’s mobility? Can the player take the role of an animal by guiding it in the first person (as in simulator games)? When the player assumes the role of an animal, what abilities does the animal have? Do the rules of the game change when a player inhabits the role of an animal?

These questions encourage students to consider how the interactive possibilities between player and virtual animals reproduce or challenge pre-existing assumptions about animals in industrialized societies. As Adam Brown and Deb Waterhouse-Watson (2016) remind us, “To varying degrees (but always to some extent), human beings learn about other animals through the symbolic status attributed to them through cultural products, and this frequently involves the naturalization of anthropocentrism.” Anthropocentrism, or the human tendency to privilege the wants and needs of Homo sapiens above the wants and needs of all other forms of life, certainly informs the design of many video games. However, playing video games does not always necessitate that players passively accept anthropocentric interactions with animals as an inevitable requirement for play. With his concept of “procedural rhetoric,” Ian Bogost provides a precise term for how video games encourage (while often allowing for degrees of freedom to resist) a particular manner of interaction between player and game world. For Bogost, “video games can make claims about the world. But when they do so, they do it not with oral speech, nor in writing, nor even with images. Rather, video games make argument with processes. Procedural rhetoric is the practice of effective persuasion and expression using processes” (Bogost 2008, 125). Processes comprise the rule-based systems by which games as computer software unfold as well as the rules that constrain the actions of players. Asking about the “rules of the game” or how and why a game constrains and incentivizes player interactions with particular game features attunes students to the ways games-as-interfaces construct rhetorical arguments.

Scaffolding Game Analysis

Before we begin playing games and analyzing the arguments they make, I provide students with an illustrative model of academic video game criticism: Gary Walsh’s (2014) article “Taming the Monster: Violence, Spectacle, and the Virtual Animal.” By seeing video game criticism in action, students recognize that their video essay projects can contribute to a visible, existing conversation in humanities disciplines. Walsh argues that “videogames create a space in which virtually anyone can commit acts of violence without being registered as such,” that video games be read as opportunities for players to subject animals to violence and to read their own actions as strictly entertainment (22). Many students initially resist Walsh’s argument. Their inclination is to dismiss the implications of game processes that reward violent interactions with nonhuman animals, suggesting instead that games are unworthy of the careful scrutiny provided more transparently rhetorical texts. Indeed, the phrase “But it’s just a game” circulates during the session we consider Walsh’s work. Working through Walsh’s essay, I urge students to examine their reluctance to 1) read video games as argumentative, and 2) consider their actions as players as participating in an argument constructed by interface with a set of game rules. With students, I ask: why does the pleasure we take in video games’ fantasy spaces preclude a critical examination of the way games rely on existing ideologies and ways of interacting between humans and animals?

To give students practice formulating critical questions about games’ rhetorical choices while also thinking about how games ask them to behave as players, I require students to play a series of free-to-play games that involve animals. Asking students to play a set of preselected games prior to their in-depth interrogation of a single game for their video essays serves two important instructional purposes. First, these games help familiarize students with common video game genre conventions. One represents a “casual game”; another lets us explore the conventions of the “first-person shooter.” By introducing students to some of the basic video game genres, even students relatively unfamiliar with game genre conventions can draw on their experiences playing these free games as a foundation for the more sustained rhetorical analysis of game conventions and rules that they undertake soon afterward. Second, I select the initial games students play because of the illustrative way each game represents animals. Rather than offer complex representations, these games are simple both in terms of controls and argument, making them excellent starting points for a more in-depth interrogation of how games make claims about animals.

For example, one of the free games I ask students to play, Linksolutions’ Pets Fun House, represents a “casual” game in which players assume the role of a new pet shop manager. Pets Fun House asks players to feed, water, and clean up after an expanding collection of dogs and cats with the objective of selling those pets to impatient shop customers. As the game proceeds, players’ in-game profits can purchase increasingly larger shop facilities and a wider range of dog and cat breeds to exchange for additional profits. After playing Pets Fun House, I can reliably anticipate that students will respond eagerly to the question: “What argument does this game make about animals?” That is, after playing the game, students identify, at minimum, that 1) Pets Fun House reduces animals to commodities, and 2) Pets Fun House simplifies the needs of companion species, the player needing only to click once per creature to alleviate hunger, thirst, and waste (the three needs that must be satisfied to successfully prepare the animals for sale).

In another of the free games I require students play, DroidCool.com’s Deer Hunter 3D (2015), students become acquainted with the genre of the first-person hunting simulator. In this game, players must shoot an increasing number of deer before time runs out in order to proceed to the next level. Each deer in the game looks and behaves identically to every other deer: they pace across the screen and remain blissfully unaware of the player’s approach. The game’s simplified representation of deer appearance and behavior prompts students to identify that this game promotes the idea that animals are repetitive, instinctual machines. Further, since the player must slay as many deer as possible within a narrowing time frame in order to proceed to the next level, students quickly see how the game’s deer have a single purpose: to “die.” The game portrays its animals not only as machinic obstacles to overcome, but also as morally and physically simple to eradicate. Here, the simplicity of the game’s interface—point and click to shoot without the need to reload or take cover in features of the landscape—implies that the act of killing deer is both easy and straightforward and, consequently, does not require player reflection. As we saw with animal memes, the ease with which video games as interfaces can make an action possible—here, the ease with which Deer Hunter 3D makes it possible for a player to kill deer—is instructive for students as they consider the rhetorical work of interfaces in general.

Work and Play: The Video Essay Project

For the image-based version of the video essay project assignment sheet, please click here.

For a text-only version of the assignment sheet, please click here.

The student artifacts included below comprise a representative sample of the video essay projects students submitted during the past two semesters of this course. Briefly, this project requires students collaborate in groups of 4-5 members each and choose a Steam-based video game to analyze from a list of games I briefly pre-screen for cost and content. Assigning a game available through Steam, a game distribution platform for personal computers, streamlines the requirement that students record their gameplay. Additionally, I tell students that their video essays should not “review” their chosen game. Rather, their video essays should analyze the game’s rhetoric and make an argument about how the game represents animals.

Importantly, I require that students compose their video essay projects for a public audience: students must upload their completed video essays to YouTube and list them as “public.” This requirement has two important pedagogical benefits. First, composing for a public audience allows students to become active knowledge producers, not simply passive consumers. That is, public video essays enable students to contribute their voices, interests, and, by the end of the process of analysis, expertise to an existing network of positions and ideas. Second, I find that students not only produce better work when composing for outside-the-class audiences, but also make more connections between the work we do in the classroom and communication practices in the “real world” when required to produce public-facing work. They see how the work of rhetorical analysis, for example, can influence and inform others. Centrally, a public-facing project teaches students a fundamental concept like the rhetorical situation by providing them a “real” audience to persuade.[2]

Finally, this project requires students to draft and revise a rough script and storyboard for their essays. Their script organizes the scope and structure of students’ voice-over narrations; it also emphasizes the importance of clear, succinct writing in projects that seem at first glance to prioritize visual and electronic modes of communication. Indeed, assigning a multimodal project like a video essay does not alleviate or dismiss the need for students to consider how and why certain “moves” in their persuasive texts become rhetorically effective. For example, student-produced video essays like Essay I on Giant Squid Studios’ 2016 game Abzû present widely-recognized indicators of an effective argument, such as discussion of counterexamples. In addition to the students’ discussion of counterexamples, Essay I demonstrates students’ attention to how the game’s mechanics (or rule-based systems) affect how players think about the role of animals in the game. Against their primary argument that the game promotes a “genuine connection” between player and virtual animals, students analyzed how the inclusion of the mechanic of “riding” animals (see between 4:23 and 5:00 in Essay I) violates said connection. They explain:

By latching on to these creatures, you can take control of their actions and use their bodies to your own benefit…The animal gives up its autonomy…establishing a hierarchical relationship…By riding these creatures, you create temporary and superficial bonds that disappear once you let go.

This piece of analysis demonstrates the thoughtful associations that students developing digital literacy skills can establish between game interfaces and game arguments. Specifically, students here articulate their perception of a link between the interface-afforded opportunity to “ride” animals in the game and the “hierarchical relationship” between human character and nonhuman animal such a rule implies.

In Clip I, students explain how Might and Delight’s 2013 game Shelter restricts player movement to incline players to think about the badger cubs placed in their care. This clip shows not only students’ rhetorical awareness (insofar as they address audience members directly by telling them which visual features of their gameplay footage to pay attention to), but also their astute attention to the relationship between the rules of the game and how those rules persuade players to feel a certain way: in this case, to invest emotionally in the badger cubs.

Many of the most effective multimodal arguments take seriously what a given medium affords in terms of opportunities for persuasion. Throughout Essay II, students use a combination of gameplay footage, video, and overlaid graphics to enhance their argument about how the visual and mechanical simplicity of Chris Chung’s 2013 game Catlateral Damage creates a fantasy of carefree nonhuman embodiment for the player. A particularly rich example takes place during 3:39 and 4:25 of Essay II. Here, students demonstrate their understanding that showing an image of a “cockroach” and “spider” followed by a series of clips of house cats provides a visceral visual reminder that we very often value the lives of (cute) animals over others. Such a difference in species’ implicit value, students claim, is central to the lack of a death mechanic in Catlateral Damage, a game they claim is largely about causing destruction with no fear of consequences.

As a final example, Essay III demonstrates students’ recognition that games can make culturally-specific arguments. Throughout Essay III, students analyzed how developer Upper One Games translated interactions between indigenous Iñupiaq culture and nonhuman animals into the game interface of Never Alone (2014). Students saw such translation occur through what they termed the “equal but different” representation of the game’s human and fox protagonists. From 5:35 to 6:59, Essay III provides a particularly astute analysis of how game mechanics can construct one argument while a game’s narrative can construct another, contradictory argument.

Despite the success of many of the video essays I received, issues that teachers of persuasive writing will be familiar with still persisted in some cases. For example, some essays did not provide sufficient evidence to support students’ claims. In other essays, students failed to articulate a clear and straightforward argument. Moreover, it is worth pointing out the ample hardware and software resources available to students at Georgia Tech as they play their games, record their footage and narration, and edit their essays. I recognize that such resources are far from universally available. Even with these challenges in mind, I am encouraged by the work students have accomplished in these video essays, and I will continue to adapt this project to help students analyze other forms of interactive technology in the future.

Reflection and Conclusion

Looking back at the results of the informal survey I administer to assess students’ familiarity with animals, I am impressed by the wide range of interpretations students developed in their video essays, interpretations unlikely to have emerged from attempts to simply apply their prior knowledge of human-animal relationships. Richard Colby, Matthew S. S. Johnson, and Rebekah Shultz Colby (2013) suggest that video games constitute “exemplar multimodal texts, aligning word, image, and sound with rules and operations constrained by computer technologies but composed by teams of writers, designers, and artists to persuade and entertain” (4). Even so, after analyzing survey data of texts selected by writing teachers for use in writing courses, Johnson and Richard Colby (2013) found that “video games are…neglected as texts to be analyzed” despite statistics that show “the sheer number of gamers and the magnitude of the game industry” (87). By bringing video games into the first-year composition classroom, I witnessed students moving away from their initial impulse to regard everyday texts as innocent and undeserving of critical inspection. An overwhelming majority of essays showed students performing thoughtful, in-depth analyses of texts with rhetorical content that once seemed invisible. As regards nonhuman animals, too, an examination of video games may train students to consider their acts of “interfacing” with animals both virtual and actual as worthy of curiosity and reflection, especially if a particular form of interaction seems only natural.