Making Reading Visible: Social Annotation with Lacuna in the Humanities Classroom

Emily Schneider, Stanford University

Stacy Hartman, Stanford University

with

Amir Eshel, Stanford University

Brian Johnsrud, Stanford University

Abstract

Reading, writing, and discussion are the most common—and, most would agree, the most valuable—components of a university-level humanities seminar. In humanities courses, all three activities can be conducted with a variety of digital and analog tools. Digital texts can create novel opportunities for teaching and learning, particularly when students’ reading activity is made visible to other members of the course. In this paper, we[1] introduce Lacuna, a web-based software platform which hosts digital course materials to be read and annotated socially. At Stanford, Lacuna has been collaboratively and iteratively designed to support the practices of critical reading and dialogue in humanities courses. After introducing the features of the platform in terms of these practices, we present a case study of an undergraduate comparative literature seminar, which, to date, represents the most intentional and highly integrated use of Lacuna. Drawing on ethnographic methods, we describe how the course instructors relied on the platform’s affordances to integrate students’ online activity into course planning and seminar discussions and activities. We also explore students’ experience of social annotation and social reading.

In our case study, we find that student annotations and writing on Lacuna give instructors more insight into students’ perspectives on texts and course materials. The visibility of shared annotations encourages students to take on a more active role as peer instructors and peer learners. Our paper closes with a discussion of the new responsibilities, workflows, and demands on self-reflection introduced by these altered relationships between course participants. We consider the benefits and challenges encountered in using Lacuna, which are likely to be shared by individuals using other learning technologies with similar goals and features. We also consider future directions for the enhancement of teaching and learning through the use of social reading and digital annotation.

Introduction

Though reports of the death of the book have been greatly exaggerated, reading and writing are increasingly taking place on screens (Baron 2015). Through these screens, we connect with each other and to the media-rich content of the Web. Within university courses, however, there remain open questions about appropriate tools for students to collaboratively and critically engage with—rather than just view or download—multimedia course materials. The most popular platforms and media are generic tools that are not specifically designed to support the learning goals of humanities or reading-intensive courses. If there were a platform designed specifically to support college-level reading, what features should it have? How would such a platform alter the teaching and learning opportunities in a college humanities course?

In this article, we introduce one such platform, Lacuna, and consider its impact on teaching and learning in a seminar-style literature course. Lacuna is a web-based software platform designed to support the development of college-level reading, writing, and critical thinking. Sociocultural educational theories locate learning in the behaviors and language of individuals as they become adept at participating in the practices of a particular community (Lave and Wenger 1991, Collins et al. 1991, Vygotsky 1980). In addition to providing access to educational content, learning technologies can be designed to make existing expert practices in the community more accessible to novices (Pea and Kurland 1987). In particular, the interactive features in a learning technology can be designed as an embodiment of expert behaviors—for example, the strategies that skilled readers use when they engage with texts, in both print and digital form.

The key example of an expert inquiry practice for our purposes is annotation. Annotation here refers to any kind of “marking up” of a print or digital text, including underlining, highlighting, writing comments in the margins, tagging sections of text with metadata, and so on. Annotation is a practice that may not come as naturally to college students as their instructors would hope. And even when students (and instructors) do engage in annotation, they may not be cognizant of how different kinds of inscribing practices on a text affect their learning.

On Lacuna, course syllabus materials are digitized and uploaded to the platform. These materials can be organized by topic, class date, and other metadata such as medium (text, video, or audio). When students and instructors open up materials, they can digitally annotate selections from any text. Annotation on Lacuna is a social as well as an individual practice, leveraging the participatory possibilities of web-based technologies (Jenkins 2009). Lacuna users can choose to share annotations with one another and hover over highlighted passages to reveal others’ comments or questions. Social annotation makes explicit and visible for students the broad array of annotation practices within an interpretive community such as a classroom and helps students co-create interpretations of texts. Students’ annotation activity on Lacuna is also made visible through a separate instructor dashboard, which helps instructors track engagement throughout the course (using D3.js dynamic javascript visualizations of annotation data). Finally, annotations can be connected across texts using the “Sewing Kit” in order to support intertextual analyses.

Since 2013, the technologists and researchers on the Lacuna team in the Poetic Media Lab have designed and developed the platform collaboratively with humanities instructors, based on the theories of learning and expert reading practices described in the following sections of this article. During this time, Lacuna has been used in over a dozen courses at Stanford and other universities, primarily in the humanities and social sciences. Across the courses, the primary authors of this article (Schneider and Hartman) have used ethnographic approaches, including classroom observations, student surveys and interviews with instructors and students, in order to understand the ways that Lacuna mediates relationships among course participants and course content.[2]

In this paper, our primary goal is to examine the shifts in pedagogical practices, and the related learning experiences, that are enabled by social annotation tools like Lacuna when in the hands of willing and engaged instructors. Learning takes place in a complex system of relationships, resources, and goals (Cole and Engestrom 1993, Greeno 1998). Across the courses which have used Lacuna, instructors have chosen to integrate the tool to various degrees. This was unsurprising, as decades of educational research have shown that introducing a new technology, no matter how well-designed, is an insufficient condition for change unless it is intentionally integrated it into pedagogical practices (Cuban 2001, Collins et al. 2004, Brown 1992, Sandoval 2014). In this paper, we present a case study of a course taught by Amir Eshel and Brian Johnsrud, the co-directors of the Lacuna project, which exemplifies the classroom dynamics that become possible when social annotation is woven into the fabric of the course. While Eshel and Johnsrud were the original designers and first users of Lacuna, they were not involved in the present analysis of their own teaching. Within the course examined in this study, we present the full spectrum of the teaching and learning experience, from the time instructors spend preparing for class to perspectives from the students.

A secondary goal in this paper is to introduce Lacuna to other practitioners and researchers who may be interested in using the tool. As a web-based educational software platform, Lacuna is licensed by Stanford University for free and open-access use. Lacuna is run on the content management system Drupal, and the Stanford Poetic Media Lab has made Lacuna available to download with an installation profile on GitHub. Like other learning management systems, such as edX or Moodle, colleges, universities, or other institutions need to sign an institutional agreement taking responsibility for their use of the software, and students and other users agree to the Terms of Use when creating an account. Lacuna is also an ongoing open-source development project. Collaborating universities, such as Dartmouth and Princeton, are currently building out their own features and contributing them to GitHub, so the platform has ongoing refinement based on code submissions from different partners.

Our final goal for this paper is to develop broader questions about and insights into social annotation practices that could apply not only to Lacuna but also to other, similar tools. We hope that some of these questions and insights will come from readers of this article who are themselves exploring the relationship of technology, pedagogy, and learning in the humanities. Our article opens by describing the design of Lacuna in great detail, and then uses a similarly detailed approach to analyze a specific use of Lacuna. In providing these “thick descriptions” (Geertz 1973) of both the technology and its use, we hope that our readers will have the opportunity to reflect on and compare their experiences, goals, and tools to ours. By so doing, we can increase our collective knowledge about the benefits and tradeoffs of social annotation in the humanities classroom, with implications for other reading-intensive courses beyond the humanities.

Annotation as an Individual and Social Practice

As a reader, annotation serves a very personal role—we make marks in the margin or between the lines as an extension of our reactions at the moment of encountering a text. Annotations are also part of our process in preparing to write a paper, a “scholarly primitive” which becomes a building block of our observations about texts (Unsworth 2000). Annotation is one of the central practices used for critical reading in an academic context, as we identify, interpret, and question the layers of meaning in a single text and across multiple texts (Flower 1990, Scholes 1985, Lee and Goldman 2015). In humanities and seminar-style courses, we hope that our students are actively reading by interacting with texts in this way. Focusing on specific parts of a work, and then articulating why the selected passage is interesting, important, or confusing, are essential steps for students in constructing their own understanding of a text (Bazerman 2010, McNamara et al. 2006). By externalizing their thought processes through annotations, it becomes more likely that students remember what they have read and gives them an artifact to work with later on.

With digital texts, annotations can be shared and made visible to other readers—annotation becomes a social act. While this may cause tensions with the personal nature of the annotation process, social annotation also opens up new channels for learning through dialogue and observation of others’ reading and interpretive practices. One hallmark of the humanities broadly, and seminar-style courses in particular, is the “dialogic” nature of the discussion: students are encouraged to explore multiple perspectives on contemporary issues and the texts under scrutiny (Bakhtin 1981, Morson 2004, Wegerif 2013). Each course member has the opportunity to use academic language and express their own ideas, leading to increasing command over new conceptual frameworks and allowing each student to participate more effectively in a “discourse community” (Graff 2008, Lave and Wenger 1991). The instructor guides negotiation between perspectives without insisting on consensus interpretations. Though there is little rigorous research on the impact of dialogic instruction in university courses, these principles have been associated with higher student performance in multiple large-scale studies of middle and high school language arts courses (Applebee et al, 2003, Nystrand 1997, Langer 1995).

With social annotation, dialogue moves from the classroom (or an online discussion forum) to the moment of reading itself. Multiple perspectives and voices become available on the text, both before the class meets and in subsequent re-readings of the texts. The visibility of these perspectives provides opportunities for students to engage productively with difference and reflect on their own practices. Through the dynamism of these differences emerges the co-construction of meaning, wherein the perspectives of each member, and the negotiations among these perspectives, contribute to a shared understanding of the meaning of the texts and topics under discussion (Morson 2004, Suthers 2006). A sense of my stance, my analyses, my strategies for dealing with difficult texts, can also become more salient in contradistinction to other visible stances (Gee 2015, Lee and Goldman 2015). The asynchronous nature of the online dialogue through annotations can also shift the dynamics of whose voices are heard within the discourse community of the class. Particularly when annotations are mandatory, even a typically quiet student or a non-native English speaker can use annotations to voice their perspective or to show to instructors that they are engaging deeply with texts and ideas.

Social annotation technologies like Lacuna have been an ongoing fascination of researchers and technology developers since networked computing became common in the 1990s. University classrooms were particularly fertile ground for experiments in social annotation, especially as computer science professors at the cutting edge of developing digital systems found themselves in the position of teaching undergraduates through traditional, non-digital means. For example, CoNote was an early social annotation platform developed over twenty years ago at Cornell (Davis and Huttenlocher 1995). Aspects of the interface design and students’ ability to access CoNote were, of course, a product of the time—annotations were only allowed on pre-specified locations in a document, and nearly half of the students used CoNote in a computer lab because their dorms were not yet wired for the Web. The anecdotal experience of these students, however, foreshadows our own design goals with Lacuna. Students successfully used CoNote annotations as a site of document-centered conversations and collaborations. Frequently, the students were able to help each other more quickly than the course assistants. Students also self-reported in surveys that they felt better about being confused about course topics because they could see through annotations that other students were also confused (Davis and Huttenlocher 1995, Gay et al. 1999). The major lesson from this early work is the potential for peer support and community-building when conversations are taking place on the text—at the site where work is actually being done—rather than through other means such a discussion forum. (See also van der Pol, Admiraal and Simons 2006 for an experiment demonstrating that discussions taking place through annotations tended to be more focused and topical, compared to the broad-ranging conversations on a course discussion forum).

Since the 1990s, a large number of social annotation tools have been developed, both as commercial ventures and as academic projects (e.g. Marshall 1998, Marshall and Brush 2004, Farzan and Brusilovsky 2008, Johnson, Archibald and Tenenbaum 2010, Zyton et al. 2012, Ambrosio et al. 2012, Gunawardena and Barr 2012, Mazzei et al. 2013; other systems, such as AnnotationStudio at MIT and MediaThread at Columbia University, have not published any peer-reviewed research on their platforms). Research conducted on these social annotation platforms has largely focused on the experiences of students or on reading comprehension outcomes tested through short reading and writing assignments. These results have ranged from positive to neutral (see Novak et al. 2012 for a meta-analysis), with major themes of students benefiting from one another’s perspectives, being motivated by annotating, and using annotations to guide their exam studying.

Other research has examined specific aspects of the social annotation dynamic in more detail. For example, Marshall and Brush (2004) examine the moment when an annotator chooses to share her annotation, finding that students chose to shared ten percent or less of the annotations that they made on each assignment. When students did choose to share their annotations, they often cleaned them up before making them public—transforming shorthand notes to self into full sentences that would be intelligible to others in the class. These moves demonstrate a level of self-consciousness about the other readers in the course as members of a group conversation. Of course, social norms for sharing online may well have shifted since the early 2000s when the study was conducted. Another key moment in social annotation is when a reader chooses to read someone else’s annotation. Wolfe (2000, 2002, 2008) ran multiple studies manipulating the annotations that students can see, with a focus on exploring the influence of positive or negative (critical) annotations. As would be expected, her subjects paid more attention to the annotated passages than the unannotated parts of the text. Moreover, with positive annotations or unannotated passages, students were more likely to focus on comprehending the text without questioning it. When faced with conflicting annotations on the same passage, however, students were more likely to work to develop their own evaluation of the statement in the text. The fact that annotations help prompt deeper responses to the reading was borne out in other studies on students’ writing from the annotated text. Freshman students who wrote essays based on an annotated text were more likely to seek to resolve contradictions in their essays, and less likely to simply summarize the text. In these studies, the presence and valence of annotations clearly altered students’ sensemaking processes and understanding of the texts.

Finally, from a pedagogical perspective, social annotations can open up new possibilities for instruction. While these possibilities are underrepresented in the prior literature, one exception is Blecking (2014), who used ClassroomSalon to teach a large-scale chemistry course. Her research reports that students’ annotations helped her and her teaching assistants diagnose student misconceptions and make instructional changes in response. In humanities courses where reading strategies are often an instructional goal, instructors can monitor students’ annotations in order to give direct feedback on students’ reading strategies and textual analysis. Instructors can, of course, also enter the dialogue on the text themselves, using annotations to guide students to specific points in the text. Additionally, social annotations can serve as an accountability mechanism for completing assigned reading in a timely fashion, because instructors will see students’ activity on the text and students will know that instructors can see this activity.

One might ask—as colleagues have asked us during talks about Lacuna—why there have been so many social annotation tools recently, and why we need another one. One major reason is that many of these tools have been used for STEM courses, with an emphasis on the question-answer interaction as students help each other comprehend concepts in the text. This type of interaction, with an emphasis on a single correct answer, lends itself to different interface interactions than the type of dialogic sensemaking in humanities courses. Even among tools that lent themselves to the goals of humanities courses, there appeared to be a lack of support for exploring intertextuality and synthesis. When the Poetic Media Lab first began designing Lacuna, there were no interfaces that allowed students to filter, order, sort, and group their annotations across multiple texts. Moreover, most existing digital annotation platforms did not have a way to conveniently make student activity throughout the course visible to instructors, as Lacuna’s instructor dashboard does. Finally, no platform that Lacuna’s initial design team surveyed included features that allowed students to write and publish work on the site. As discussed below, by including these features, Lacuna is designed to support an integrated reading and writing process, allowing students to sort, organize, and visualize their annotations, and then write and publish prose or media in the form of short responses or final papers, with a built-in automatic bibliography creator for materials hosted on the course site.

From a research perspective, prior work has included limited investigations about the day-to-day experiences of teaching with a social annotation platform, and connecting the experience of learners as a result of particular instructional decisions. Learning takes place in a complex system of relationships and resources (Cole and Engestrom 1993, Greeno 1998) and introducing new technologies can lead to unforeseen tensions as well as the expected opportunities. Understanding these dynamics in detail is vital for critically considering the possibilities and trade-offs in practice that social annotation platforms, like Lacuna, introduce. This is the goal of the empirical work presented in the “Teaching with Lacuna” and “Learning with Lacuna” sections, which follow after the in-depth introduction of the platform in the next section.

What Does Lacuna Look Like?

Lacuna is an online platform for social reading, writing, and annotation. Like Blackboard, Canvas, and other familiar learning management systems, Lacuna serves as a central organizing space for a course. Instead of hosting readings to be downloaded, however, Lacuna provides a set of shared texts and other media that students and instructors read and annotate together on a web-based interface.[3] In the vocabulary of software design, Lacuna has a number of “affordances,” platform features that create or constrain possibilities for interaction (Norman 1999). These affordances shape, though do not dictate, the central interactions of the digital learning process, namely learners’ interaction with content and interpersonal interactions among learners and instructors (Garrison, Anderson and Archer 1999; 2010).

This section introduces the reader to the affordances of Lacuna in terms of three central practices of humanities and seminar-style courses: critical reading, dialogue, and writing. Through literature reviews and conversations with our faculty collaborators, the project team identified critical reading, dialogue, and writing as vital to the humanities and thus a shared goal—explicit or implicit—of the majority of courses using Lacuna. As researchers and designers, framing the platform in terms of the major goals of the discipline helps us better understand what we might hope for in teaching and learning activities and learning outcomes.

Annotation as Critical Reading and Dialogue

As discussed above, annotation is one of the central practices that experts use for critical and active reading in an academic context. Research on the reading practices of faculty and graduate students has shown that these readers make arguments about the rhetorical and figurative form of texts, usually by connecting the text to other pieces of literature and theory. As they read, faculty and students annotate the text with observations about potential themes, building evidence across specific moments in the text (Lee and Goldman 2015, Levine and Horton 2015, Hillocks and Ludlow 1984). Learning technologies can be designed to embody expert practices in a way that makes those practices more accessible to novices (Pea and Kurland 1987), which is why annotation is central to the design of Lacuna.

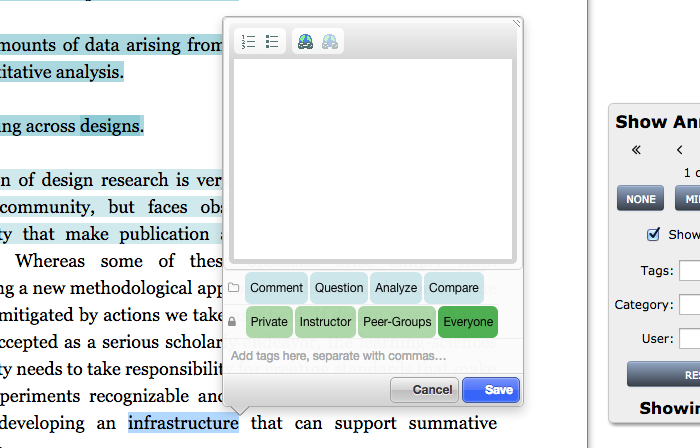

Figure 1 below shows the annotation prompt that appears when a reader on Lacuna highlights a passage.[4] Readers may choose to make a comment or to simply highlight the passage. Lacuna instructors frequently require students to produce a minimum number of written annotations per week towards their participation score in the course.

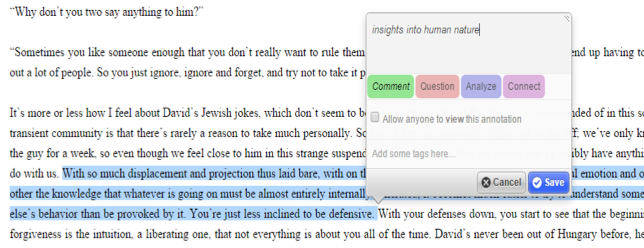

Lacuna gives students the option to keep their annotations private or share them with the class. When students choose to share their annotations, they are contributing to a form of online dialogue that can also be extended into the classroom (see figure 2). Readers can use the Annotation Filter to choose whether to see one another’s annotations. Faculty who use Lacuna often make note of students’ annotations and adapt their classroom instruction to meet students’ interests or struggles with texts. In the “Teaching with Lacuna” section, we will examine how this blurring of the line between the classroom and the online preparation space affected the experience of the instructors in preparing for and teaching one specific humanities seminar.

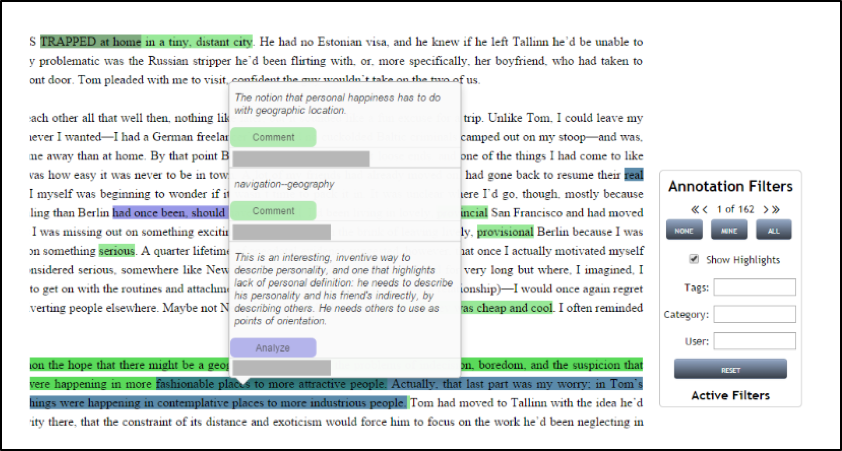

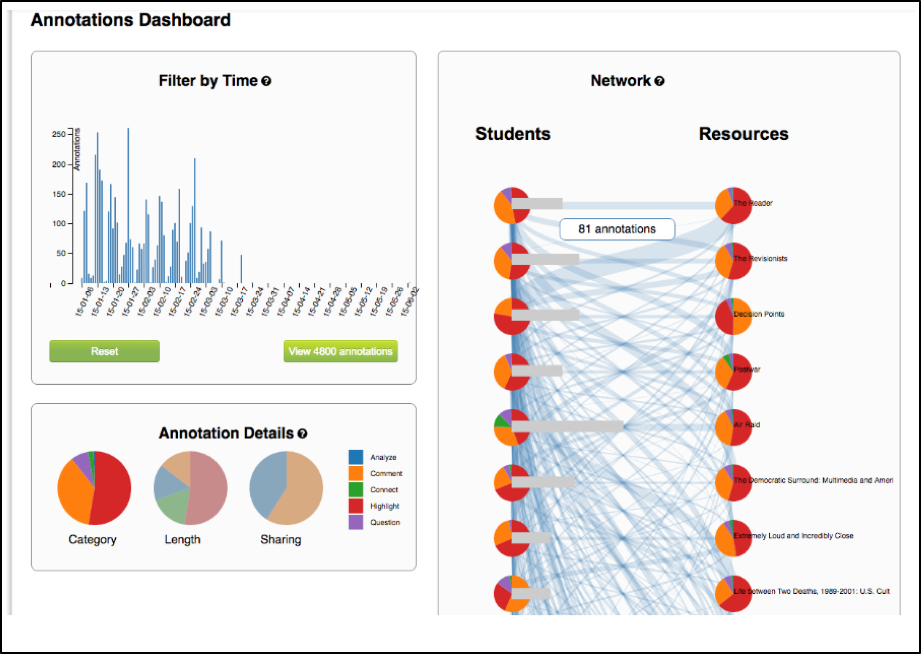

One of the features that sets Lacuna apart from other social annotation platforms is the “Annotation Dashboard,” which provides an aggregate visualization of students’ use of the platform (see figure 3). The dashboard is updated in real-time and is interactive to allow for multiple ways of viewing the annotation data. Currently, there are three different types of analysis offered by the dashboard. “Filter by Time” is a bar graph that illustrates the relative number of annotations made on any given day of the course. “Annotation Details” shows via pie chart how many of each category of annotation there are, how long the annotations are, and how many of them are shared versus private. Finally, “Network” is broken down further into “Resources” and “Students”; this section allows instructors to see how many annotations each resource received and by which students.

Figure 3: The Instructor Dashboard on Lacuna, showing student annotation activity throughout the Futurity course

Each of the dashboard visualizations interacts with all of the others. For example, clicking on a student name in the “Network” section causes only her data to appear in all three categories. We can then see which texts a student annotated most heavily, how many of her annotations were highlights and how many were comments or questions, and when she did the bulk of her highlighting. Clicking the “View annotations” button not only tells us how many annotations she made in total, it takes us to a table in which we can view all of them. The dashboard therefore makes it quite easy to see not only if students have met a required number of annotations, but also which texts they have found most worthy of annotation, whether students are highlighting or engaging through commenting/questioning, and when students tend to do their reading. As we will see shortly, having this information has a significant impact on the instructor’s experience of teaching the course.

Annotation as Part of the Writing Process

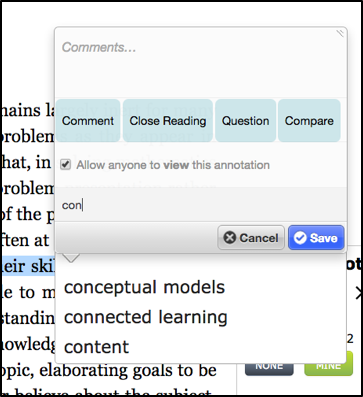

Lacuna also includes features that position the annotating and critical reading process as part of a longer-term project of understanding multiple texts or writing a paper about them. Reading in humanities courses is usually part of an integrated reading-and-writing process, where students produce their own texts about the texts they have read or about the issues raised in the texts (Biancarosa and Snow 2004, Graham and Herbert 2010). Expert readers look for patterns, mapping out a text and drawing explicit connections to other texts they have read (Snow 2002, Lee and Goldman 2015). In Lacuna, annotation metadata allows readers to tag and categorize their annotation as a visible record of the mapping and connection processes (see figure 4). For example, readers can tag annotations with a particular theme or topic (e.g “World War II”, “definition”). Lacuna readers can also categorize their annotations by the activity on the text (e.g. as a “Comment” or a “Question” or “Analysis”). Through these tags and categories, Lacuna readers begin to develop a structured characterization of the text. Tags on Lacuna can be suggested by students, or pre-specified by the instructor. By using both open and pre-specified tags, instructors can guide students’ reading while still allowing students to engage in personalized processes of intellectual discovery.

In addition to tags, critical reading in Lacuna is linked with the writing process through two features: Responses and the Sewing Kit. “Responses” are pieces of student writing shared on the Lacuna platform. Responses can be directly linked to the texts and annotations that they reference. Lacuna also lets students annotate Responses, allowing their work to be interacted with in the same way as the work of established authors that is hosted elsewhere on the site. Enabling student writing to be annotated and commented on also creates the ability for peer-review by other students or real-time feedback on student work by the instructor.

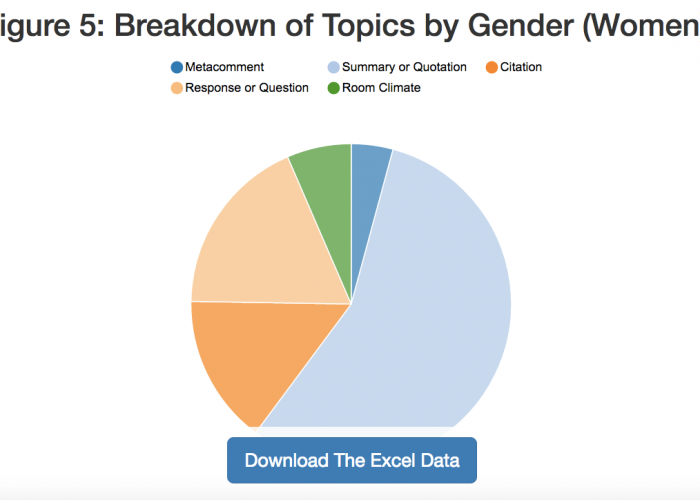

The Sewing Kit allows for the automatic aggregation and sorting of all annotations in one place. Students can explore the Sewing Kit based on tags or keywords and create collections, called “Threads,” of quotations organized by theme (see figure 5). Threads can be used by individual readers as a thought-space for initial analyses. They can also be developed collaboratively to compile passages and annotations from multiple readers that are relevant to a theme discussed by the class.

Figure 5: A Sewing Kit “Thread” from Futurity, in which multiple student annotations on one document have been collected around a single theme of “Memory.”

The Sewing Kit is one of the most unique features of Lacuna, with few equivalents in other digital annotation tools. From a pedagogical perspective, manipulating online texts in a way that makes the complementary nature of reading and writing visible can support increased metacognition about the relationship between reading, annotating, analysis, and writing. The usefulness of being able to sort and search annotations across many texts will be apparent to anyone who has ever had to organize a large amount of reading for a project. Moreover, the visibility of each of these steps on Lacuna can be used to assess students’ developing understanding of texts, as well as their skills in interpreting and arguing for a particular interpretation of a text.

The features of Lacuna were designed in accordance with the pedagogical ideals of the humanities classroom: close reading, the exchange of ideas through discussion, and analytical writing that is anchored in the text itself. It was the hope of the research and design team that Lacuna would encourage certain expert practices in student users. In the following section, we will provide an in-depth analysis of one use of the tool in a humanities seminar that was co-conducted by Lacuna Co-Directors Amir Eshel and Brian Johnsrud. In this analysis, we will consider in detail the impact of Lacuna on both faculty instructional practices and student learning.

Findings

This section presents two complementary perspectives on the integration of Lacuna into an upper-level literature course. First, we describe the faculty perspective and provide a snapshot of how social annotations can be integrated into a classroom discussion. Second, we describe the student experience, drawing on surveys and interviews with two students in the case study course.

Teaching with Lacuna

There is no single way to teach using Lacuna—or any social annotation tool, for that matter. Of the dozen or more instructors who have used the Lacuna at Stanford and other institutions, each has made his or her own instructional design choices about how deeply to integrate the platform into course activities. On the “light integration” end of the spectrum, some instructors used Lacuna as the equivalent of a course reader. In these classes, students were asked to read and annotate in the shared online space, but there were no clear expectations that they would interact with one another online through their annotations. There was also little acknowledgment of their online activities during class sessions. On the “deep integration” end of the spectrum, instructors read students’ annotations and responses in advance of class and integrated them into class discussion; in these courses, a minimum number of annotations per week were often expected and counted towards a participation score.

In this section, we will closely consider a “deep integration” course: “Futurity: Why the Past Matters”, co-taught by Amir Eshel and Brian Johnsrud, Co-Directors of Lacuna. The integration of Lacuna was evident both in how the instructors prepared for class and in activities and discussion during class. In many ways, “Futurity” exemplifies the ways in which social annotation tools like Lacuna can be intentionally used by instructors to create a more student-centered and learning-centered humanities seminar. By examining in detail the instructional and classroom experience in Futurity, we hope that our readers will have the opportunity to reflect on and compare their experiences, goals, and tools to ours.

The “Futurity” Course

“Futurity” is a comparative literature course deeply concerned with contemporary culture’s engagement with the past in order to imagine different futures. Focusing on specific historical moments of the last sixty years, the course topics explored the relationship between narrative, representation, interpretation, and agency. The course materials included fiction, non-fiction, film, television, and graphic novels[5], making use of Lacuna’s multimedia capabilities and allowing the class to consider how different media representations shape our understandings of the past.

Futurity was first taught using Lacuna in Winter 2014, using an early version of the platform. This article will focus on the 2015 iteration of the course, but it is worth noting that the 2014 version of Futurity played a crucial role in the development of Lacuna itself. Based on feedback from students, features which are often found in online and hybrid learning settings—a wiki and discussion forums—were eliminated in favor of discussion through annotation within the texts. The content of the course also shifted, based partially on the annotations left by students in 2014, which gave the faculty insight into which texts were most generative for discussion.

The 2015 course required 20 annotations per week from each student. This was reduced from the previous year’s requirements based on student feedback indicating that higher requirements led to annotating in order to get a good grade, rather than annotating as a way of increasing comprehension and engagement. The student population of the 2015 class was a small seminar, yet remarkable for its diversity of academic backgrounds and ages of students. Across 10 students, the course participants ranged from postdoctoral fellows in philosophy, to graduate students in comparative literature, to undergraduates in the interdisciplinary Science, Technology, and Society (STS) major, under which Futurity was cross-listed.

Integration of Lacuna into the “Futurity” Course

One of our key research questions was how the visibility of students’ reading with Lacuna changed instructor practices. For Eshel and Johnsrud, a simple yet powerful shift was the ease of ascertaining which students had done the reading and how well they had understood the texts—questions which, as many instructors know, can consume considerable classroom time and assessment work (such as reading quizzes or short reading response papers). With Lacuna, the instructors could easily see whether students had annotated and how they had reacted to the readings. This meant that preparing for a class session of Futurity was significantly different from preparing for courses that did not use Lacuna. In an interview, Eshel noted that it made “class preparation and [his]… intimate knowledge of [his] students” much easier, and that the experience of teaching was intensified. Both Johnsrud and Eshel emphasized that having their students’ thinking rendered visible by the platform ahead of time increased their own engagement with the course. Students also appeared to be more prepared for class. This resulted, according to Eshel, in a “quicker pace” and in conversation that was “more intense and more meaningful.” Based on students’ annotations and written responses to the reading, the instructors were able to immediately dive into lecture or discussion.

Visible annotations also changed the focus of class preparation. Johnsrud described his and Eshel’s process of preparing for class with Lacuna as akin to drawing a Venn diagram, where one circle represented the students’ interests, as evidenced by annotations and responses, and the other was the topics that the instructors wanted to cover. Johnsrud and Eshel generally tried to focus the class discussion and any lecture material on the overlapping area. This approach could be challenging, however, simply for logistical reasons: the students in Futurity were just as likely to complete their reading at the last minute as any other group of students, which meant that not all annotations could be incorporated into the discussion. Other Lacuna instructors have dealt with this by setting a reading deadline twenty-four hours before class. In terms of topics, sometimes students’ interests and questions diverged from the themes that Eshel and Johnsrud wanted to cover. Incorporating students’ perspectives thus required considerable flexibility from Johnsrud and Eshel, as well as a willingness to cede some control of the classroom discussion agenda to the students’ questions or interests as reflected in their annotations.

Examining students’ online work in advance of class sessions was a task primarily taken on by Johnsrud and the course’s teaching assistant (TA). The TA would send emails to Johnsrud and Eshel that included information such as “hot spots” in the reading (that is, places where students had annotated heavily), trouble spots where students had visibly struggled with the text, interesting annotations or responses for starting a conversation, and overall trends he observed in their annotations. The TA frequently used the Sewing Kit to aggregate the annotations of multiple students under themes relevant to the course content, such as “Agency” or “Memory.” This took about 2-4 hours each week (the course met for 1.5 hour sessions, twice a week). Both instructors noted in interviews that such an approach could be demanding without a teaching assistant.

Eshel and Johnsrud also used annotations to get to know their students as readers and thinkers. Johnsrud said, “After Week 1, I could tell you so much about each student, how they think, what they struggle with, what kind of level they are at, that had nothing to do with any class behavior.” In order to bridge online and offline dialogue, Johnsrud or Eshel often focused discussion on a “hot spot” in the text, addressing overall themes in students’ comments. At times, Eshel or Johnsrud would ask a student to expand verbally upon a particular annotation they had written before class. Eshel and Johnsrud generally let the students know ahead of time if they were going to be using one of their annotations to generate discussion, so that the student did not feel they were being cold-called and had time to prepare a few thoughts.

These practices and their pedagogical outcomes are illustrated particularly well by a class session that took place on during the 5th week of the 10-week quarter. For this class, students read a 1989 essay about the dissolution of Communism. Although Futurity was primarily a literature course, Eshel and Johnsrud often paired a literary text with a theoretical one and pushed students to place the two texts in dialogue with each other. For this class session, students annotated the essay 164 times, with just over half of the annotations (92) including comments (the remainder were highlights, which are a signal of engagement with the text, but engagement that may be less reflective than annotations). In their annotations, students took issue with the author’s ideas, particularly as they related to class and race in Western culture. The students’ disagreement with the author led to particularly rich annotations. Two examples of such annotations include:

“This seems completely outlandish and impractical. I disagree with Kojeve… how can he theorize on such a ‘universal homogenous state’ when all of history is speaking against such a utopia. If one can even call it that; isn’t it our differences and varying opinions which make the world fascinating? His theory seems impossible” (Jenna[6])

“This is a highly debatable and suspect statement. I wouldn’t say that US society is a class-less society. Granted its’ [sic] class structure is different from the class structure of, say, India. But there definitely is a class system, which many individuals do not even want to acknowledge. Consider a city like Baltimore and how even its city planning is based on a class categorization.” (Amanthi)

Prior to class, Johnsrud and Eshel had agreed upon certain annotations and themes that they wished to address. They spent the first twenty minutes on a mini-lecture contextualizing the importance of 1989 as a turning point in the end of the Cold War. They then gave students five minutes to look over their own annotations, re-clarify their thoughts about the text, and come up with a few points they wished to discuss. Ryan, a doctoral student, chose to focus on an annotation he had written in which he questioned the author’s phrase “the end of ideological evolution.” Ryan expanded upon his critique of the phrase in class, and Eshel pushed back, asking if an argument that is “wrong” or inaccurate can yet be a productive tool. There followed a discussion between Ryan and Eshel not only about the author’s ideas, but also about how to discuss a piece of criticism that might be at once useful and problematic. Eventually, Ryan welcomed James, an undergraduate in Comparative Literature, into the discussion by way of one of James’s annotations that he made before class, and which Ryan had viewed: “James had a great annotation about that,” Ryan said. James picked up the conversation from there. In this dialogue, both the instructors and the students had an awareness of one another’s online activity, which was elaborated upon during the in-person discussion. As many instructors of discussion-based courses know, one of the most difficult aspects of discussion can be encouraging students to respond to each other, and not solely to the instructor. In this case, Ryan’s awareness of his peers’ ideas prior to entering the classroom encouraged him to expand the conversation beyond his exchange with Eshel.

In addition to encouraging responses and dialogue among and between students, deliberate integration of online discussion into the classroom also appeared to have a democratizing effect. Later in the discussion, Eshel asked Amanthi, a doctoral student in comparative literature, to weigh in on the discussion. Drawing on her annotations, Amanthi neatly summarized her three main problems with the author’s argument about the notion of socioeconomic class. Eshel responded by contextualizing the author’s remarks in terms of the time the piece was written. Both instructors had wished to address the questions about class raised by Amanthi in her annotations, and they were able to do this by asking her to expand upon her online work. While the instructors may have been able to bring the topic into the discussion without looking to a student, doing so served to acknowledge the work the students did while reading and emphasize that the discussion was a dialogue between equals with valid perspectives.

This particular in-class discussion illustrates a few of the practices of integrating social annotations into the classroom. By using Lacuna as a window into students’ reading, Eshel and Johnsrud were able to pinpoint the exact places in the text that generated the most frustration, confusion, or disagreement in their students. While they were not necessarily surprised by students’ reactions to the text, as they had taught this essay previously to students who found it problematic, they were able to use specific criticisms, attached to individual claims and sentences on the text, as a springboard for discussion. To get the conversation rolling, the instructors were able to call on students they knew to have annotated heavily and thought deeply about the text. Those students were, in turn, able to manage the discussion themselves, such as when Ryan asked James to talk about his annotation. Students whose comments built on their annotations were often succinct and articulate, perhaps because they were better prepared to contribute than they would have otherwise been. Finally, the integration of students’ online ideas into the classroom had an equalizing effect; although both instructors had points they wished to raise, they were able to do so by calling on students who had themselves already raised those points in their annotations.

This Week 5 class session also demonstrates a type of negotiation that can take place between the students’ interests and the instructors’ instructional agenda in classes that integrate Lacuna into the classroom conversation. Throughout the conversation, the instructors attempted to steer the conversation away from the shortcomings of the essay and toward the reasons they had had the students read it. Eshel noted early on in the discussion that, “A text like this is nothing but a tool . . . a tool we use to do all kinds of other things.” Eshel stated explicitly that he wanted the students to consider whether the author might be wrong and productive at the same time. But it was clear, from both the students’ annotations and the ensuing discussion, that many of them were resistant to this perspective on the text. The instructors acknowledged and built upon the work that students had done already, thereby creating more authentic dialogue; but the students, being aware of how much work both they and their peers had already done on the text, appeared at times to be less willing to follow where an instructor might lead them. While students’ initial interpretations of a text may also be codified before class with a print text, there is a possibility that digital and social annotation may prime in students more fixed interpretations before class. This trade-off between guidance and discovery will be discussed more thoroughly in the concluding remarks.

Learning with Lacuna

From the foregoing analysis, it is clear that instructors can deliberately leverage students’ online activity with Lacuna to promote intellectual engagement and dialogue within their classrooms. What is the online reading experience like for students? Across surveys of students in Futurity and six other courses using Lacuna (N=45), digital annotation with Lacuna appears to have both benefits and drawbacks. Here, we briefly discuss student survey results before presenting an in-depth analysis of one-on-one interviews with students in the 2015 Futurity course.

For most of the students surveyed, annotation was a familiar strategy which they used frequently, according to self-reported habits. When asked about their goals in annotating, students largely described using annotations to meet a particular goal, such as when they did not understand something as they were reading or to return to at a later point. They also used highlighting and underlining to mark parts of the text that they wanted to remember or which simply seemed notable for their language. When it came to the physical experience of reading and annotating, it is worth noting that over half of the students surveyed expressed a preference for reading on paper, citing eyestrain and the freedom to make multiple types of marks (such as lines, circles, or arrows) as the main benefits. But when comparing Lacuna to other digital reading experiences, students remarked favorably upon the ease of annotating, particularly in contrast with the poorly-scanned PDFs that they had encountered in other courses. They also appreciated the organizational benefit of all-in-one access to online texts.

It was social annotation, however, that emerged through the surveys as the most salient aspect of Lacuna, compared to both paper and digital reading environments. In open text responses describing their experiences, students reported an appreciation of the opportunity to hear one another’s perspectives and learn from one another as well as from the instructor. This was particularly true for less advanced students in courses such as Futurity, which included graduate students along with both major and non-major undergraduates. Students described that seeing others’ annotations drew attention to particular aspects of the text, clarifying aspects of the writing or helping them see what questions would be useful to ask of the text. In a course similar to Futurity, where the instructor frequently brought students’ annotations into class, several students commented appreciatively on the “continuity” between reading before class and the subsequent class discussion.

Survey respondents also emphasized that timing matters when it comes to the social experience. For example, one student said he was usually the first to read and comment, so he didn’t have the opportunity to experience others’ annotation unless he took the time to return to the text after class. On the flip side, one student honestly shared that he appreciated others’ annotations drawing attention to aspects of the text when he was reading last-minute before class. Multiple students preferred exploring others’ comments on a second read-through of the text, rather than the first, so they would have the chance to form their own impressions of the text. The annotation filter in Lacuna facilitates these modes of reading, allowing students and faculty to choose whether to see no annotations; only their own annotations; selected users’ annotations; or annotations from everyone in the course. (See figure 2, above.)

Surveys can provide a high-level perspective on the experience of a group, but interviews accompanied by work products—in this case, annotations on Lacuna—are a powerful research tool for going more deeply into the nuances of an experience. Reflecting the emphasis on social annotation in the surveys, the following section draws on interviews with two students in Futurity, “Jenna” and “Allegra,” in order to explore the processes by which social annotation creates opportunities for peer learning. Jenna and Allegra were selected to be interviewed as part of a larger research project looking across multiple courses using Lacuna. Based on recommendations of faculty and their observed levels of platform and classroom engagement, we felt that Jenna and Allegra were representative of students who were highly engaged with the course and the platform.

Exploring Social Annotation from the Student Perspective

Jenna and Allegra were both seniors at the time they were interviewed. As humanities majors, Jenna and Allegra were experienced annotators, building on years of instruction in high school and use of annotation in previous undergraduate courses. With Lacuna, however, they each noted that the platform allowed them to annotate more extensively than they were accustomed to doing on paper. The “endless” virtual margin and the speed of typing meant that for both students, the material features of the platform augmented aspects of a pre-existing individual practice. Even more salient, however, were the ways that the platform created a stronger sense of community and new opportunities for social learning. Jenna eloquently expressed the connection to other course participants that the platform enabled her to feel: “It’s like all of our head space is kind of in the same area. […] I’ll just be like oh, this is what Amanthi was thinking when she read this part. How interesting, it’s a Sunday afternoon and we’re both reading this. […] It’s like there is constant fluidity, between when I’m in class and outside of class.” Just as the instructors sought to connect online and offline activity, students like Jenna were making these connections themselves.

The collegial nature of the course community appeared to be a crucial element for supporting peer learning. “I have learned just as much from my peers in the course as [from] my instructors,” Jenna noted at two different points in her interview. She described social reading as an additive process, where her own understanding of the text was enhanced by the perspectives of others: “That’s the beauty of it. It’s because we have all of these minds bringing together these very fragmented understandings of the text. Then it just only adds to yours.” Pointing to examples from the course, Jenna clarified that these “understandings” can be references—to a film or to a Bible passage, for example—as well as interpretative statements. Moreover, each of these understandings, including her own, is incomplete – “fragmented” across multiple annotations and across multiple minds. Together, however, they represent a more complete understanding of the text than a single reader would be able to generate by herself.

Unpacking the social annotation process that enables this more complete understanding, however, reveals multiple opportunities for an individual to engage socially, or alternatively, remain solitary in their interpretive process. As explored in the Marshall and Brush (2004) research, the first decision in social annotation whether to share at all. For some students this appears to be a more sensitive issue than for others, with concerns about looking stupid—or, as expressed by some graduate students in surveys and informal conversations, the fear of not looking sufficiently clever and impressive. But as the quarter progressed in Futurity, sharing was the norm, rather than the exception. This was due in part to the default setting of “public” on annotations, which meant that students needed to check a box to intentionally opt out of sharing each time they hit “save” on an annotation. Over time, students also had more practice exposing their opinions without negative feedback. Another incentive may have been the instructors’ use of annotations and students’ written responses in the classroom discussion. As Allegra noted, “It definitely feels good [when they mention my annotations in class]. They acknowledged that you did a good job […] and they also teach the class, like, in accordance to some extent with what you said about the text, which is also really cool.”

Other reasons that students shared their annotations were because they “didn’t care” (Jenna) if someone saw what they wrote—perhaps a typical perspective from the social media generation —or if they had a specific audience in mind. In particular, our interviewees looked for opportunities to provide new information that would enhance the reading experiences of their peers. Allegra explained that she was far more likely to annotate rather than highlight if she was pointing out something that was not “obvious” in the text, such as references to outside texts or events: “[W]ith the Mrs. Dalloway annotation, for example […] I felt the need to point that out to people who might not have made that connection.” Allegra exhibits a relatively high level of awareness of what her peers are likely to know, as well as what kinds of insights count as novel rather than rudimentary. Jenna framed her contributions in a slightly more personal and conversational way. In her interview, she gave examples of annotations that felt important for her to make public on texts that she “disagreed with,” noting that she “really want[ed] people to know” about this opinion so it would “add something to the class discussion.”

The second aspect of social annotation is choosing to read others’ annotations. In the interviews, it became clear that in the dialogue taking place through social annotation, not all utterances are necessarily “heard” by others. If the student is reading early in the week or in the hour before class, there will be a different version of the text with different amounts of annotations available. Moreover, the annotations which are at the time of reading available can be shown or hidden using filters on the text. Then, even if the reader chooses to show annotations with the filter, it is up to that reader to read any particular annotation by hovering over the text to show the annotation. Finally, once an annotation is read, the reader may choose to reply to it or make another note in parallel—or, they can simply notice what the other annotator has written and then move on, rather than actively engaging with it. Each annotator has their own preferences about this, which may also vary by text. Describing their approaches generally, our interviewees had slightly different perspectives. Jenna reads others’ annotations when she gets “curious about what other people wrote on a given page, […] I try to do that pretty often.” Allegra said that she “always makes sure to click ‘all annotations’ [on the filters], when I’m reading so I can see what people have said already. That often informs the way I look at things in the text.” From these students’ experience, it is not clear whether different strategies for reading others’ annotations would be more or less effective for different kinds of texts, or for interpretive practices with different goals.

In discussing what made a “good” annotation, Jenna and Allegra generally focused on the informational content and novelty of the annotation. As an example of a beneficial annotation, Allegra pointed to an annotation on Ian McEwan’s novel Saturday, in which Jason had noted that McEwan is “orientalizing” the word “jihad,” creating distance between the reader and Arabic culture. “That wasn’t something I had thought about,” she explained. Jason’s interpretation added another lens for Allegra to analyze the work being done by the text and the choices made by the author. Even though the annotation was not addressed directly to her, it was another perspective that she could build on in her own interpretation of the text. Sometimes, however, Jenna and Allegra did not view other students’ annotations were not as particularly useful. For example, Allegra described somewhat disparagingly the “pointless,” single-word annotations that some students made, which were a reaction to the text without adding specific analytical detail. Jenna exhibited a similar response to “obvious” annotations, describing “a couple of times where people have been, like, this is a recurring trope, and I’m like…yeah. You didn’t need to tell me that.” Nearly in the same breath, however, both Allegra and Jenna acknowledged that others in the class could have benefited from the annotations that they did not find personally useful at the time. Jenna noted, for example, “Maybe for other people, they didn’t think of that as a trope […] So, it could definitely help someone else.” The unique knowledge and interests of each annotator, who are each readers of one another’s annotations, means that it may be difficult to find annotations that are useful to all readers—a challenge not unique to social annotation but shared with all annotated editions of texts.

With these examples, a vital aspect of social annotation becomes evident: the act of annotating has multiple goals and as a result, there are multiple ways to understand whether annotation is a productive utterance in the online discourse community. Social annotation is a way of reading simultaneously for oneself and for the community. The individual reader, traditionally ensconced in a paper book, thinks entirely of himself. With social annotation, a diverse audience emerges—an audience including an instructor who is in a position of evaluation and other students who can be “told” new information. Moreover, both instructors and students are fellow participants in a dialogue which can be carried out in class as well as online. Finally, the reader is also an audience member herself, for the performances of others in her class. The mental model of the activity of social annotation, then, is multifaceted, requiring a level of self-awareness (and other-awareness) significantly beyond that of being a private reader.

Concluding Remarks

By equipping learners to engage individually and collectively with texts across media, Lacuna and other social annotation platforms are designed to encourage critical thinking and sensemaking, skills which are at the core of disciplinary work in the humanities and vital to 21st-century citizenship. Critical reading has long been a hallmark of the humanities and a skill which the traditional seminar has sought to foster in its students; however, the practice itself has often been all but invisible to instructors. By transforming reading into an activity that is done socially, rather than in solitude, Lacuna created a bridge between the physical classroom and online reading space in Futurity.

Social annotation in the Futurity course allowed the instructors to get to know their students better and to incorporate student perspectives more fully into the dialogue of the course. By glimpsing their peers’ interpretations of a text during class preparation, students were able to start engaging in dialogue before they entered the classroom. They became more comfortable with one another and had increased opportunities to learn from each other as well as from the professor, developing a multi-faceted perspective on texts. These changes in instructor and peer learning practices appear to have created strong student investment in the course and more authentic dialogue during class discussions. The social annotation affordances of Lacuna rendered students’ reading visible to instructors and other students, and thus expanded the dialogic space of the course.

But dialogue isn’t always easy. Social annotation appears to create new demands on students and instructors alike to negotiate one another’s perspectives and reflect on the goals of their participation and practices. For students, this negotiation and self-reflection largely takes place during reading. Encountering a chorus of voices on a text means that these voices must be sorted through, accepted, questioned, or ignored. Being a member of that chorus means constantly choosing whether to sing or be silent. These choices build on skills that students have likely have developed through in-person discussions, as well as pre-existing solitary reading strategies, but combines them in new ways. In educational research, this type of self-monitoring and intentional use of resources is known as “self-regulation” (e.g. Bandura 1991, Schunk and Zimmerman 1994). Self-regulation is a relatively sophisticated set of competencies, which must be taught, practiced, and discussed. Similarly, social annotation is an activity which will likely function best when self-reflection about the practice is encouraged and there are ongoing conversations in a course about how to best engage in it.

Instructors working with social annotation tools like Lacuna are presented with the opportunity to incorporate students’ interests and struggles with texts into teaching, which can include the potentially discomfiting need to cede to the students some measure of control. Even if faculty are comfortable with this, it highlights the tension that must be negotiated between the desire to allow students the space for intellectual discovery and the desire to guide their learning along a pre-specified path. While the tension between student-led discovery and instructor-led guidance is present to some degree in any seminar, pedagogical opportunities to support discovery are heightened by the ways that Lacuna makes reading practices and student voices more visible on the text itself. To balance these goals, instructors who use Lacuna, or similar software which emphasizes student perspectives, would be well-served to reflect on their desired learning outcomes for the class and adjust their use of the platform accordingly. Such self-reflection is also useful when considering how much time an instructor wishes to spend combing through student annotations for use in the classroom; student annotations are effectively an additional text that an instructor needs to prepare each week, and the learning goals of a specific course will dictate how much time an instructor will wish to spend preparing that text.

Generally, the influence of Lacuna on the course dynamics of Futurity appeared to be positive. We observed and heard about high levels of student preparedness, active reading habits, and deep engagement in course topics among both students and instructors. While these changes were certainly shaped by the design and affordances of the platform, they cannot be regarded as given for all users of Lacuna or other social annotation tools. It is likely no coincidence that, of the dozen or so courses that have utilized Lacuna in recent years, the course with the deepest integration of the platform was the only one in which Lacuna was used two years in a row. The lessons learned from the first year of teaching were critical in shaping both the technological changes made to the Lacuna platform and the ways that Eshel and Johnsrud chose to leverage the platform when they taught the course again the following year. This illustrates the importance of intentionality, reflection, and iteration in both the design of the platform and instructors’ use of it—lessons which go beyond Lacuna and social annotation tools to learning technologies broadly. For designers, it is essential to think of instructional technologies as dynamic, rather than static; they must adjust to the pedagogical needs and goals of instructors. Instructors, in turn, must carefully consider how best to use a platform to achieve their goals. Thoughtful and reflective design of the technology, and thoughtful and reflective use of the tool in the classroom, are equally important to achieving a deep level of pedagogical impact.

Future Directions

Our case study has surfaced themes of authority, agency, and new forms of relationships in courses where technology makes student activity visible to instructors. We plan to investigate these themes further as we continue to research and develop the Lacuna platform and engage with researchers investigating comparable learning technologies. While the current study focused on classroom dynamics, a vital question that needs further consideration is the specific way in which student learning is influenced by the pedagogical moves that Lacuna enables. To pursue this avenue of research, we are in the process of developing rubrics for characterizing the reading strategies expressed in online annotations. Using annotations as evidence of critical reading and dialogic practices is an opportunity that is relatively unique to digital learning environments which capture traces of student activity. These data provide critical insights into student thinking, both on an individual and collective level, and can be used as a type of formative assessment for tracking learning over time (Thille et al. 2014).

At Stanford, Lacuna continues to be used for seminar-style courses similar to Futurity, as well as in courses in other departments and larger, lecture-style courses. Lacuna is also being used at a variety of other universities—visit www.lacunastories.com for a full list of our collaborators. Each of these collaborators are doing exciting work to make the platform their own. We are particularly pleased to be supporting local community college instructors who teach composition, as well as reading and writing courses at the basic skills level. In these partnerships, we are building on the insights from this case study and other unpublished case studies and observations. For example, we encourage active reflection about annotation practices and goals. This includes strategies for gradually increasing the level of integration of Lacuna into homework assignments and classroom activities, in order to give both instructors and students the opportunity to adjust their habits.

In our current research and partnerships, we continue to iteratively refine the design of Lacuna, while building our theoretical conceptions of the co-creation of meaning through social annotations. Throughout this work, we seek to support learning and instructional practices in a way that balances the strengths of participatory digital media with the strengths of in-person human interactions.

Notes

[1] Note about authorship and affiliation: This paper presents a case study of a course taught by Amir Eshel and Brian Johnsrud, the co-directors of the Lacuna project in the Poetic Media Lab. While Eshel and Johnsrud were the original designers and first users of Lacuna, they were not involved in the present analysis of their own teaching. Rather, all interviews, surveys, and classroom observations—as well as the subsequent analysis of that qualitative data—were conducted exclusively by the primary authors (Schneider and Hartman). As members of the Poetic Media Lab, Schneider and Hartman are participant-observers who have served as instructional designers to help instructors plan their courses and have analyzed research data to contribute to the ongoing improvement of the platform. This level of involvement is typical for researchers in the “design-based research” paradigm of the learning sciences (Brown 1992, Collins et al. 2004, Sandoval 2014). Some level of bias is inherent in participating in and observing a project at the same time. Nevertheless, in any form of participant-observation, it is always the hope that any considerations that may be overlooked due to close proximity is more than compensated for by the first-hand observations of practice that such inquiry affords.

[2] Please see note 1 above on authorship and affiliation to learn more about the participant-observer relationships of Schneider, Hartman, Eshel, and Johnsrud to the analyses presented in this paper.

[3] The site can also be used for films, videos, audio, and images. The vast majority of media in the course syllabi of our faculty reflect, however, the traditional focus of the academy on written texts. To reflect this trend and maintain clarity in our writing, we will use the term “reading” throughout the paper. But when we say “reading,” note that these claims may be equally important for viewing, listening, etc.

[4] Figure 1 and other screenshots in the paper are from the version of Lacuna used in the case study course described in this paper. The most recent version of Lacuna refines the privacy settings for annotations to allow readers to only share their annotations with an instructor or to share annotations with a specific group of peers, in addition to keeping annotations private or sharing them with the entire class. These changes were made in response to feedback from students and instructors who wanted more fine-grained control over who could see their annotations.

[5] A common question about Lacuna is the copyright status of materials. Lacuna supports the uploading of any digitized course or syllabus material, such as text, images, video, or audio files. As with any Learning Management System (LMS)—such as Canvas, Blackboard, edX, etc.—instructors are responsible for the copyright status of materials they upload. With each upload, instructors are asked to indicate the copyright status of the material, such as open access, Creative Commons, limited copyright for educational purposes, etc. Because the platform has secure logins limited to students enrolled in courses, instructors at Stanford have had a good deal of success getting free or reduced copyright fees for course materials that do not fall under fair use for educational purposes. Publishers seem particularly accepting to digitized materials on Lacuna because they are not easily downloaded and disseminated as PDFs, which is the way that many other LMSs deliver content.

[6] All student names in this article are pseudonyms.

Bibliography

Ambrosio, Frank, William Garr, Eddie Maloney and Theresa Schlafly. 2012. “MyDante: An Online Environment for Collaborative and Contemplative Reading,” Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy, no. 1.

Applebee, Arthur N., Judith A. Langer, Martin Nystrand, and Adam Gamoran. 2003. “Discussion-based approaches to developing understanding: Classroom instruction and student performance in middle and high school English.” American Educational Research Journal 40, no. 3: 685-730.

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. 1981. The dialogic imagination: Four essays by MM Bakhtin (M. Holquist, Ed.; C. Emerson & M. Holquist, Trans.).

Bandura, Albert. 1991. “Social cognitive theory of self-regulation.” Organizational behavior and human decision processes 50, no. 2: 248-287.

Baron, Naomi S. 2015. Words onscreen: The fate of reading in a digital world. Oxford University Press.

Bazerman, Charles. 2010. The Informed Writer: Using Sources in the Disciplines, 5th Edition. Fort Collins: The WAC Clearinghouse.

Biancarosa, Gina, and Catherine E. Snow. 2004. Reading next: A vision for action and research in middle and high school literacy. Alliance for Excellent Education.

Brown, Ann L. 1992. “Design experiments: Theoretical and methodological challenges in creating complex interventions in classroom settings.” The Journal of the Learning Sciences 2, no. 2: 141-178.

Cole, Michael, and Yrjö Engeström. 1993. “A cultural-historical approach to distributed cognition.” Distributed cognitions: Psychological and educational considerations, 1-46.

Collins, Allan, John Seely Brown, and Ann Holum. 1991. “Cognitive apprenticeship: Making thinking visible.” American educator 15, no. 3: 6-11.

Collins, Allan, Diana Joseph, and Katerine Bielaczyc. 2004. “Design research: Theoretical and methodological issues.” The Journal of the Learning Sciences 13, no. 1: 15-42.

Cuban, Larry. 2009. Oversold and underused: Computers in the classroom. Harvard University Press.

Davis, James R., and Daniel P. Huttenlocher. 1995. “Shared annotation for cooperative learning.” In The first international conference on Computer Support for Collaborative Learning, pp. 84-88. L. Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Farzan, Rosta, and Peter Brusilovsky. 2008. “AnnotatEd: A social navigation and annotation service for web-based educational resources.” New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia 14, no. 1: 3-32.

Flower, Linda. 1990. “Introduction: Studying cognition in context.” Reading-to-write: Exploring a cognitive and social process, 3-32.

Garrison, D. Randy, Terry Anderson, and Walter Archer. 1999. “Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education.” The Internet and Higher Education 2, no. 2: 87-105.

Garrison, D. Randy, Terry Anderson, and Walter Archer. 2010. “The first decade of the community of inquiry framework: A retrospective.” The Internet and Higher Education 13, no. 1: 5-9.

Gay, Geri, Amanda Sturgill, Wendy Martin, and Daniel Huttenlocher. 1999. “Document‐centered Peer Collaborations: An Exploration of the Educational Uses of Networked Communication Technologies.” Journal of Computer‐Mediated Communication 4, no. 3.

Gee, James Paul. 2015. Literacy and Education. Routledge.

Graff, Gerald. 2008. Clueless in academe: How schooling obscures the life of the mind. Yale University Press.

Graham, Steve, and Michael Hebert. 2010. Writing to read: Evidence for how writing can improve reading: A report from Carnegie Corporation of New York. Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Greeno, James G. 1998. The situativity of knowing, learning, and research. American psychologist, 53 no. 1: 5-10.

Gunawardena, Ananda and John Barr. 2012. “Classroom salon: a tool for social collaboration.” In Proceedings of the 43rd ACM technical symposium on Computer Science Education, pp. 197-202. ACM.

Hillocks, George, and Larry H. Ludlow. 1984. “A taxonomy of skills in reading and interpreting fiction.” American Educational Research Journal 21, no. 1: 7-24.

Jenkins, Henry. 2009. Confronting the challenges of participatory culture: Media education for the 21st century. MIT Press.

Johnson, Tristan E., Thomas N. Archibald, and Gershon Tenenbaum. 2010. “Individual and team annotation effects on students’ reading comprehension, critical thinking, and meta-cognitive skills.” Computers in Human Behavior 26, no. 6: 1496-1507.

Langer, Judith A. 1995. Envisioning Literature: Literary Understanding and Literature Instruction. New York: Teachers College Press.

Lave, Jean, and Etienne Wenger. 1991. Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge university press.

Lee, Carol D., and Susan R. Goldman. 2015. “Assessing literary reasoning: Text and task complexities.” Theory Into Practice just-accepted.

Levine, Sarah, and William Horton. 2015. “Helping High School Students Read Like Experts: Affective Evaluation, Salience, and Literary Interpretation.” Cognition and Instruction 33, no. 2: 125-153.

Marshall, Catherine C. and AJ Bernheim Brush. 2004. “Exploring the relationship between personal and public annotations.” In Digital Libraries, 2004. Proceedings of the 2004 Joint ACM/IEEE Conference on, pp. 349-357. IEEE.

Mazzei, Andrea, Jan Blom, Louis Gomez, and Pierre Dillenbourg. 2013. “Shared annotations: the social side of exam preparation.” In Scaling up Learning for Sustained Impact, pp. 205-218. Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

McNamara, Danielle S., Tenaha P. O’Reilly, Rachel M. Best, and Yasuhiro Ozuru. 2006. “Improving adolescent students’ reading comprehension with iSTART.” Journal of Educational Computing Research 34, no. 2: 147-171.

Morson, Gary Saul. 2004. “The process of ideological becoming.” Bakhtinian perspectives on language, literacy, and learning, 317-331.

Norman, Donald A. 1999. “Affordance, conventions, and design.” Interactions 6, no. 3: 38-43.

Nystrand, Martin. 1997. Opening Dialogue: Understanding the Dynamics of Language and Learning In the English Classroom. New York: Teachers College Press.

Pea, Roy D., and D. Midian Kurland. 1987. “Cognitive technologies for writing.” Review of research in education, 277-326.

Sandoval, William. 2014. “Conjecture mapping: An approach to systematic educational design research.” Journal of the Learning Sciences 23, no. 1: 18-36.

Scholes, Robert E. 1985. Textual power: Literary theory and the teaching of English. Yale University Press.

Schunk, Dale H., and Barry J. Zimmerman. 1994. Self-regulation of learning and performance: Issues and educational applications. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.