Interactive Technology for More Critical Service-Learning?

Possibilities for Mentorship and Collaboration within an Online Platform for International Volunteering

Willy Oppenheim, Omprakash

Joe O’Shea, Florida State University

Steve Sclar, Omprakash EdGE

Abstract

International service-learning programs have rapidly expanded in higher education in recent years, but there has been little examination of the potential uses of interactive technology as a pedagogical tool within such programs. This paper explores a case study of an interactive digital platform intended to add more reflexivity and critical rigor to the learning that happens within international service-learning programs at colleges and universities. The digital platform under consideration, Omprakash EdGE (www.omprakash.org/edge), facilitates collaboration between students, international grassroots social impact organizations, and a team of mentors that supports students before, during, and after their international experiences. The authors represent both sides of a collaboration between Omprakash EdGE and a program at Florida State University which works to help students find affordable, ethical, and educational opportunities for international engagement. The paper begins with an overview of the troubled landscape of international service-learning within higher education, and an explanation of the authors’ rationale for collaborating to develop a new program model revolving around a digital platform. Then it discusses the ways in which the authors have sought to cultivate international learning experiences that are dialogical, reflexive, personal, and experiential, and it explains how a digital platform has been central to this effort by enabling students to build relationships with host organizations, engage in pre-departure training, and receive support from mentors. It then explains some of the challenges and successes the authors have encountered in their collaboration thus far, and concludes with reflections on the pedagogical constraints and possibilities for interactive technology within programs aiming to generate critical consciousness through international engagement.

I. Introduction

Within the broader trend of internationalization sweeping through colleges, universities, and even some high schools in the United States and elsewhere (Gacel-Avila 2005; Harris 2008), the phenomenon of international service-learning raises a number of interesting pedagogical and programmatic questions. As educational institutions in resource-rich countries (the so-called “Global North”) increasingly endorse opportunities for students to travel to resource-poor countries (the so-called “Global South” or “developing world”) to volunteer or intern in settings that include schools, clinics, orphanages, and community centers, what forms of student learning are they hoping to promote, and how do they assume that this learning actually unfolds? What are the ethical and pedagogical principles —if any—that inform the design and implementation of international service-learning programs?

It is well-established that young people are leaving their home countries to volunteer abroad at an unprecedented rate (Dolnicar and Randle 2007; Hartman et al. 2012; Mcbride and Lough 2010, 196; Ouma and Dimaras 2013). Some aspects of this trend are not new: its roots reach back at least as far as the founding of the United States Peace Corps in 1961 and the United Kingdom’s Voluntary Service Organisation (VSO) in 1958, and are entwined with older trends of faith-based international mission work. Yet regardless of these various historical precedents, researchers agree that the trend has spiked dramatically in recent decades, spurred on by both government programs and a huge range of program offerings in the private sector (Rieffel and Zalud 2006; Leigh 2011, 29). Recent data suggest that over 350,000 individuals aged 16–25 engage in some form of international volunteering each year (Jones 2005). Within the United States, tens of thousands of young people per annum volunteer through non-profit organizations such as churches and charities and through for-profit companies that chaperone group volunteer trips or “place” volunteers with foreign “community partners” (Rieffel and Zalud 2006). Recent reports estimate the value of this emergent “voluntourism” industry at anywhere from $150 million to over $1 billion per annum (Mintel 2008; Stein 2012).[1] Meanwhile, whether under the banner of creating global citizens, preparing students to compete in a global knowledge economy, or fostering intercultural competence, colleges and universities are seeking new partnerships, developing new programs, and mobilizing new discourses that all celebrate the value of immersive, non-traditional educational experiences in international settings. Within this context, programs that revolve around international service-learning have become increasingly popular, and such programs have been the subject of a considerable amount of recent academic research (e.g. Crabtree 2008; Green and Johnson 2014; Hartman et al. 2014).

Against this backdrop, academics and mainstream media outlets alike have recently put forth well-justified criticism of international volunteering (e.g. Biddle 2014; Hickel 2013; Zakaria 2014). Some authors (e.g. Ausland 2010) have usefully delineated between various forms of this phenomenon within and beyond universities—distinguishing, for example, between mission trips, slum tourism, middleman companies that “place” individual volunteers, and faculty-led group service trips. Many argue that the practice of sending untrained, unskilled young people into sensitive foreign contexts on short trips for the purpose of “serving” is a paternalistic impulse that smells of neocolonialism (e.g. Crossley 2012; Simpson 2004). At the same time, a growing body of peer-reviewed research has argued for the socially and personally transformative potential of student volunteering through university service-learning programs, especially when those programs take an explicitly critical stance and explicitly orient themselves towards the pursuit of social change (e.g. Crabtree 2008, 2013; Hartman and Kiely 2013; Mitchell 2008).

The authors of this paper represent a collaboration between the director of Florida State University’s Center for Undergraduate Research and Academic Engagement and the directors of Omprakash EdGE, a web platform that connects prospective volunteers with autonomous grassroots social impact organizations and provides intensive volunteer training and mentorship via an online classroom. We share many of the same concerns and hopes described above, but our aim here is not to restate the common refrain that “good intentions are not enough,” nor to offer another aspirational but abstract vision of what service-learning programs “should” achieve. Instead, we identify three common characteristics of service-learning programs that we find to be deeply troubling, and then explain our ongoing attempt to confront and improve upon these programmatic features via an innovative model that revolves around an interactive digital platform. By sharing the case study of our own experience, we aim to raise new questions about the educative capacity of interactive technology within the sphere of international service-learning, and to generate further debate and collaboration in this direction.

Our collaboration grew out of a shared concern that many, if not most, organizations in the business of selling or facilitating volunteer opportunities meet one or more of the following three conditions: 1) they act as a middleman; that is, they “place” volunteers with organizations or in communities from which they are distinctly separate; 2) they charge high fees for this service and more or less guarantee a placement to those who pay these fees; and 3) they promote their work by insisting that a) volunteers will be “making a difference” regardless of their background or qualifications, b) even a little bit of help is “better than nothing,” and therefore c) no significant pre-departure training or preparation is necessary (see Ausland 2010; Citrin 2011; Hartman et al. 2012). We contend that the convergence of these common program features is deleterious to student-volunteers and the organizations they purport to serve.

This paper centers on our attempt to develop an interactive digital platform that enables alternatives to these trends, and its central question is whether this model is indeed a viable one. Circling around this question are many others: If international service-learning is inherently a distance-based and loosely-defined educational experience, then how do we track learning, and what can be the role of technology in this tracking? How can a digital platform be used to remediate many of the broader problems of service-learning and ‘voluntourism’? How can an interactive digital classroom and mixed-media curricula be integrated toward that end? What role can a trained mentorship team play in facilitating learning before, during, and after students’ international trips? And most crucially, in a world characterized by stark inequalities, is it possible to use an interactive digital platform as a vehicle for critical pedagogy that sparks social and personal transformations?

In what follows, we attempt to answer these questions by sharing data and reflections from our own experience. We begin by elaborating our guiding pedagogical principles and then describing the online volunteer-matching platform, classroom, and mentorship system that are central to our program. Then we offer qualitative and quantitative data to illustrate some of the challenges and successes we have encountered thus far. We conclude by reflecting on the possibilities for interactive technology as an avenue towards more critical and transformative service-learning.

II. Programmatic Origins and Pedagogical Principles

Founded in 2004, Omprakash is an interactive digital platform that enables vetted international partner organizations to build profiles, post positions, and recruit volunteers. Prospective volunteers search and apply for positions posted by Omprakash partners, and partners have full autonomy to determine when and if they offer a particular position to a particular applicant. Volunteers pay for their own travel and in-country living expenses, but pay no program fee to Omprakash in exchange for the connective services offered by the Omprakash platform. In early 2012, Omprakash administrators launched Omprakash EdGE (Education through Global Engagement) as an attempt to actively confront the most problematic aspects of the service-learning industry described above: namely, that volunteers are often provided with little to no pre-departure training and mentorship, and that the learning half of “service-learning” is often a disconcerting grey area. The EdGE program couples volunteer trips with a 12-week pre-departure online classroom, a dedicated mentor, and a required field-based inquiry that culminates in a Capstone Project documenting local perspectives about the social issue(s) that the volunteer’s host organization is working to confront. The program is tuition-based, and one of the motivations for its design was to create sustainable, not-for-profit revenue to support the broader Omprakash platform. Omprakash sought university collaborators for the pilot year and found a strong partner in Florida State University (FSU).

In the fall of 2012, Omprakash and Florida State University’s Center for Undergraduate Research and Academic Engagement (CRE) partnered to create an FSU Global Scholars program (http://cre.fsu.edu/Students/Global-Scholars-Program) that would offer a combination of online training and immersive international volunteer opportunities to several dozen FSU students per year. A particular focus of the program is to recruit participants who are from low-income backgrounds and are first-generation college students, as this population is often underrepresented in these types of experiences and stands to benefit greatly (Finley and McNair 2013). In the first iteration (’12-’13 academic year), 37 students were selected to be Global Scholars by CRE administrators. These students each participated in the EdGE online classroom during the spring semester and then spent at least two months during the summer with one of Omprakash’s international partner organizations. In the second iteration (’13-’14 academic year), 28 students participated, and the online classroom was complemented with weekly in-person meetings among the Global Scholars on the FSU campus. At the time of writing, we are in the midst of the third iteration of the EdGE/Global Scholars collaboration, with 49 students involved.

Our work together has revolved around four pedagogical principles. First, we believe that the learning in international service-learning should be dialogical: learning should emerge via interactions with others and exploration of different perspectives, and various “truths” should be uncovered and interrogated in an ongoing process of exploration, rather than received as static “facts.” Second, learning should be reflexive: it should encourage students to reflect on their own positionality, to recognize and share their own biases, and to understand the process of learning about others as inextricable from a process of learning about selfhood and subjectivity. Third, learning should be personal, meaning that it should emerge through human relationships characterized by empathy, camaraderie, compassion, and humor. Finally, learning should be experiential, meaning that it should be grounded in empirical inquiry and exploration, and that students’ international experiences should recursively inform each other’s ongoing learning.

We make no claim to the originality of these guiding principles—indeed, we readily acknowledge the extent to which our own work has drawn inspiration from the broader trends of constructivist epistemology and critical pedagogy, in particular the work of Paulo Freire (1970). Yet our unique challenge has been to apply these principles to the creation of interactive technology intended to facilitate and support international engagement. The next section provides further details about why and how we have attempted to do so.

III. The Omprakash EdGE Digital Platform: Rationale, Functionalities, and Possibilities

Rationale for Using Interactive Technology

The prominent role of interactive technology within the EdGE/Global Scholars program is a response to several key contextual points. The first contextual point is one of geography and logistics: a digital platform is the most obvious solution to the parallel challenges of enabling students to connect directly with potential host organizations around the world, and also enabling students to maintain contact with each other and to maintain some semblance of intellectual continuity before, during, and after their field positions. Likewise, the chronological flexibility of digital learning means that a wider range of students can find ways to integrate the EdGE pre-departure curriculum into busy schedules.

The second contextual point concerns program costs and accessibility to a diverse group of students: in contrast to chaperoned “voluntourism” trips, the Omprakash digital platform can operate at scale for relatively minimal overhead costs, and thus Omprakash experiences are financially accessible to students whose less-privileged backgrounds might render them unable to afford more expensive “voluntourism” trips.[2] The key difference is that Omprakash does not spend administrative resources on placing volunteers or chaperoning trips; instead, its digital platform allows individuals and organizations to connect organically and arrange their own plans via direct communication. Omprakash invests time and resources into the initial vetting of its partner organizations to ensure a degree of quality and reliability, but the ongoing vetting process is largely driven by users’ reviews of their experiences, and this is another example of the ways in which Omprakash has been able to expand and strengthen its network without incurring expenses that must be passed on to users.

The third contextual point concerns the institutional and bureaucratic inertia faced by administrators at FSU and many other universities: despite a genuine intent to integrate rigorous academic content with students’ international experiences, universities often lack the funding and institutional will to incentivize or allow faculty to teach accredited interdisciplinary courses that explicitly prepare students to approach international service-learning with intellectual seriousness (Crabtree 2013; Hartman and Kiely 2014). Against this contextual backdrop, it made sense for FSU’s CRE to use the Omprakash EdGE online platform instead of developing a new on-campus course.

Browsing and Applying for Volunteer / Internship Positions

Omprakash administrators developed their volunteer matching platform as a deliberate alternative to the dominant “placement” model in which middlemen restrict direct contact between volunteers and their host organizations prior to arrival, and volunteers are not required to apply for specific positions. The basic rationale for this platform is that it provides greater power and autonomy to host organizations that tend to be marginalized within the dominant “placement” model.

In the dominant model, middleman organizations have little incentive to allow for direct dialogue between volunteers and hosts, because doing so might allow the volunteer to sidestep the middleman and avoid paying the middleman’s fees. Consequently, host organizations possess little to no autonomy to determine which volunteers might (or might not) be a good fit for their organization’s needs, values, and specific position openings. Likewise, volunteers have limited to no opportunity to learn more about different potential hosts and decide which one might be the best fit for their specific skills and interests.

The Omprakash model reverses this pattern by empowering partner organizations with full autonomy to solicit applications for specific positions, and to accept or reject applicants as they see fit. In addition, this programmatic feature is also an important component of students’ learning experiences: by requiring students to apply for specific positions and communicate directly with Omprakash partners, Omprakash challenges the embedded paternalistic assumptions that NGOs working in resource-poor contexts are desperate for foreign help, and that “anyone can do it.”

The EdGE Classroom

Course content in the EdGE digital classroom is divided into separate weeks that are sequentially accessible. Weeks are clustered into thematic sections, and each week is oriented around a single essential question. For example, the theme of Weeks 1–3 is “Good Intentions and Unintended Consequences,” and the essential question of Week 1 is “What might be wrong with international volunteering?”

Each week is divided into three sections: Learn, Respond, and Browse. The Learn section (see Figure 1) of each week is further divided into slides in which Omprakash administrators arrange learning content: a reading excerpt, an embedded video, a photo collage, a public service announcement from the Omprakash narrator, or any combination of the above. At the base of each slide, students are able to write observations and browse the observations of their peers. The Learn section of each week contains anywhere from ten to twenty slides and is designed to require 1–2 hours to complete. Upon completing the Learn section of a given week, students enter the Respond section (see Figure 2) and submit a written reflection or recorded video to a prompt related to the week’s essential question and associated content. After submitting their weekly response, students enter the Browse section (see Figure 3), where they explore and comment upon the responses of their peers. The end result is three ways for students to interact with classroom content and each other on a weekly basis: observations in the Learn section, responses in the Respond section, and comments in the Browse section. All participants are notified with an email whenever their response receives a comment, and mentors are notified with an email whenever their mentees post an observation or response.

Figure 1. Cropped screenshot of a slide within the Learn section of last year’s EdGE/Global Scholars classroom.

EdGE Mentorship

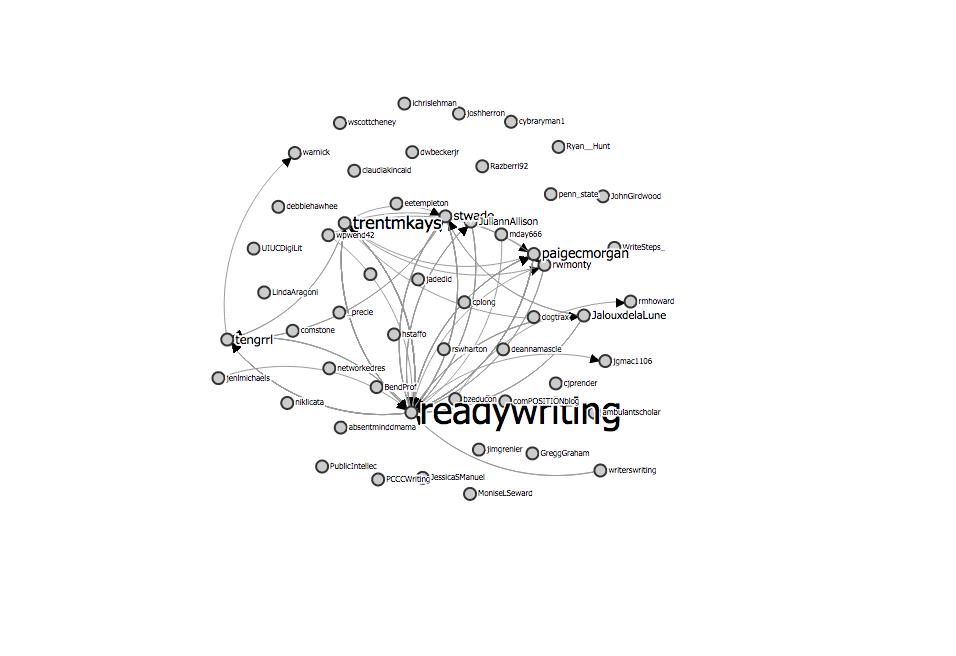

In contrast to a typical Massive Open Online Course (MOOC), we sought to ensure that student experiences within our online classroom would involve a significant degree of personalized mentorship and instruction. With this in mind, Omprakash administrators solicited applications and built a team of EdGE Mentors who would work with FSU Global Scholars as they worked through the EdGE online classroom. The EdGE Mentor team is comprised mostly of graduate students and young professionals with deep experience as researchers and practitioners in fields such as international development, public health, gender studies, and anthropology. EdGE Mentors are geographically dispersed—the current team of seventeen Mentors is spread across locations including Atlanta, Berlin, New York, Oxford, Quito, Port au Prince, and Toronto—but collaborate with students and with each other via the EdGE digital classroom. For each cycle of the Global Scholars program, each mentor is matched with a handful of mentees and is expected to maintain contact with his or her mentees before, during, and after the mentees’ field positions. Mentors are compensated on a per-student basis.

The mentorship team has multiple nodes of contact with mentees. Firstly, mentors make themselves available to mentees via email and video calls. As students progress through the online coursework, mentors schedule “office hours” with their mentees, usually via Skype or Google+. Omprakash administrators request that mentors hold office hours at least four times throughout the 12-week pre-departure classroom, and mentors use this time to answer questions and build personal rapport with their mentees. Secondly, within the classroom itself, mentors are engaged in almost exactly the same way as their mentees: each week, mentors write observations, responses, and comments. Within the Browse section, mentors are required to provide a substantial comment to each of their mentees’ responses. Mentors are welcome to provide comments to any student, even if the student is not one of their designated mentees. While these comments are public to all users, the online platform also affords mentors the opportunity to send private weekly feedback to their mentees.

Blended Learning

Upon acceptance into the Global Scholars program, students are enrolled in a one-credit, pass-fail course during the spring semester. The on-campus course is facilitated by CRE administrators and meets weekly. These meetings are usually devoted to answering logistical questions and giving students time to discuss content encountered in the EdGE classroom thus far. These meetings constitute a key feature of the collaboration between Omprakash EdGE and the CRE: while the EdGE digital classroom provides space in which students can explore content and discuss with mentors and each other, the weekly on-campus meetings add another layer of personal interaction to the experience.

EdGE Curriculum and Capstone Projects

Rooted in Paulo Freire’s notion of conscientization (“raising critical consciousness”), the EdGE curriculum is designed to help students move beyond the superficial urge to ‘help others,’ and to work towards more holistic and reflexive understandings of the intersecting contexts in which they and their host partners are situated. The curriculum begins by challenging students to reflect upon the intentions and assumptions that underlie their desires to volunteer abroad. It dedicates a week to deconstructing the catch-all term “culture.” Another week is devoted to exploring the complexities of conflicting local interest groups and power dynamics that are often obscured by overly-romanticized notions of “helping the community.” Three weeks explore intersections of social, economic, and environmental inequality, and thereby help students locate themselves and their host organizations in relation to global configurations of power. The latter part of the curriculum teaches research methods—particularly the tools of ethnographic observation and community-based participatory research (CBPR)—so that students can complete observer-activist Capstone Projects which document the roots of a complex social issue and are meant to be shared with all members of the Omprakash network as well as other audiences back home.

Monitoring and Evaluation

The Omprakash digital platform allows Omprakash administrators to easily track each student’s observations, responses, and comments throughout the duration of the twelve-week pre-departure curriculum, and to qualitatively assess how a given student’s understandings seem to shift (or not shift) over time. Likewise, the platform also allows Omprakash administrators, EdGE Mentors, and FSU administrators to easily answer quantitative questions such as which pieces of classroom content elicit the most student responses, which mentors have the most consistent back and forth dialogue with their mentees, and how trends in classroom participation vary between students with differing background characteristics.

To supplement these data sources, we also administer surveys to our students on a periodic basis. Students complete a pre- and post- survey that builds upon established survey instruments, such as the Global Perspectives Inventory (https://gpi.central.edu/) and the College Senior Survey (HERI), and also includes original questions and constructs. In addition, students offer qualitative feedback and reflections on the quality of our program via surveys administered at the midpoint and conclusion of the pre-departure curriculum and upon returning home from their field positions. Finally, Omprakash administrators also solicit feedback from Omprakash partners about the contributions of each student-volunteer.

All of this is to say that we have managed to accumulate abundant data reflecting student experiences within our program. However, we will be the first to acknowledge that conducting meaningful analysis of this data is much more challenging than simply collecting it. In the next section, we attempt to draw some inferences from the various forms of data we have collected thus far.

IV. What We’ve Learned—Challenges and Successes

Having provided an explanation of the roots and structure of our program and collaboration, we now offer a deeper analysis of the challenges and successes we have encountered during our collaboration thus far. We focus on three core aspects of our digital platform: the volunteer matching system, the EdGE classroom, and the remote mentorship model.

Matching Volunteers and Partner Organizations

By requiring potential volunteers to apply for positions, establish dialogue, and build rapport with potential host organizations before they leave home, we encourage a bridging of the real and imagined gulfs that separate the two parties. In addition to reducing our administrative burden and thus making our program more affordable and accessible to students from a wide range of backgrounds, this aspect of our program actualizes a key dimension of our ethos: by allowing volunteers and hosts to engage autonomously, exchange information freely, and establish a preliminary relationship, we enact a preventive strategy to discourage distorted relations, perverse incentive structures and perpetuated biases.

Omprakash has been refining this aspect of its platform for a decade, and the platform has facilitated thousands of fruitful collaborations between volunteers and partner organizations. However, our experience with this platform has also uncovered some troubling ironies related to digitally-based dialogue and collaboration. To state the obvious: technologies intended to connect people do not always result in increased connectedness or in successful collaborations. Prospective volunteers can be very fickle when communicating with partners: in many cases, they delay in answering emails; they forget about scheduled meetings—whether due to time zone confusion or other distractions—and they express themselves in casual, lackadaisical terms which partners sometimes interpret as immature or unprofessional. Given that Omprakash partners are real organizations confronting real social issues and are not pop-up projects that exist only to facilitate feel-good volunteer experiences, this sort of digital interaction with prospective volunteers can be disconcerting or even offensive.

Omprakash prides itself on its commitment to providing an alternative to the dominant “placement” model, and collaborators at FSU and other universities share this commitment. However, at times it seems as though some students would be much more comfortable if Omprakash would just “place” them on a volunteer trip and save them the trouble of needing to browse real organizations and apply for specific positions. Likewise, some parents and university administrators balk at the lack of “on-site supervision” within the Omprakash model. Of course, all partners provide their own “on-site supervision,” but it seems that the embedded concerns of some parents and administrators will not be soothed unless supervision comes in the form of a well-credentialed American or European chaperone. The Omprakash digital platform is meant to facilitate direct collaboration between diverse people and organizations, but some prospective volunteers, parents, and university administrators seem that to prefer paying a high premium for a guaranteed “placement” rather than grapple with the complexities and uncertainties of building relationships with locally-run social impact organizations that may or may not actually want their help. The irony here is that volunteering abroad is ostensibly a process of collaboration, but many prospective volunteers seem intimidated by the fundamentally collaborative ethos that underpins the Omprakash platform and would prefer crisply packaged “voluntourism” products designed for mass consumption.

The EdGE Classroom

On the whole, FSU Global Scholars have interacted deeply and positively with the Omprakash EdGE online classroom. There was marked improvement in the level of engagement from the first year of the program (’12–’13) to the second (’13–’14). We attribute this to two main factors. First, FSU administrators facilitated on-campus weekly meetings in the second iteration of the program. Providing this structure seemed to help spur participation. Second, Omprakash administrators gave the EdGE curriculum a thorough makeover before the second year based on feedback from first year students. Omprakash administrators added a great deal of new content, removed content that had not resonated, and developed new tactics for structuring the material in the Learn section. For example, in the first year only one piece of content (reading, video, etc.) was put onto each slide, which meant that some weeks had over 20 slides. In the second year, to whatever extent possible, slides were crafted to deliver a specific message and multiple pieces of content were arranged on a single slide to tell that story.

The post-course evaluation completed by 82% (23/28) of the 2013-2014 Global Scholars provides a clearer snapshot of students’ experience in the online classroom. Only one student disagreed with the statement “I found the classroom intuitive to navigate,” and all students agreed that “the classroom was well-organized.” Nineteen of 23 (83%) students agreed that the weekly content was “stimulating” and 20 (87%) agreed that “the flow of the course from week to week was logical.” Nineteen (83%) agreed with the statement “I valued the opportunity to engage with peers and mentors in the weekly forums.” In response to a request for general feedback, one student wrote:

I liked how it had a curriculum set up that consisted of a learning, responding, and browsing stage. It really makes me feel engaged with my peers and administration. I liked how it felt like we were in a live class. It was enjoyable to learn things online at our own pace.

With regard to self-reported learning in this evaluation, 100% of students agreed with the statement “I am a better prepared international volunteer because of this course” (of which 14 (61%) “strongly” agreed). This is encouraging, but even more encouraging is the overwhelmingly positive written feedback, such as:

I really loved how Omprakash opened my eyes to a whole new world of international aid, public health, anthropology, and research that I’ve never known about.

This program changes your perspective on international volunteering and issues like no other. It helps you reevaluate any prejudices and biases you may not even be aware you have, and learn how to best be an informed and engaged intern. It gives you extremely valuable resources and a network of people to help along the way.

I’m sure that if I were left to my own devices, I would have been more likely to literally wait until possibly even now to START preparing. It made me consider a lot of things that I wouldn’t have considered, and throughout taught me several things I will use over the course of my volunteering experience.

IT was the absolute BEST program I could ever recommend to anyone looking to volunteer abroad. It was the most eye opening experience of my undergraduate experience.

It is exciting to find students expressing this level of appreciation for a web-based learning platform. The final quoted comment reads like a typical testimonial about a ‘life-changing’ experience in another country, and thus is all the more fascinating given that it was written weeks before the volunteer even left home.

Feedback like this makes us confident about the depth of learning that occurs in our online classroom, but we still see a great deal of room for improvement. The structure of our Learn section requires students to click through each slide, but it is difficult to gauge how carefully or carelessly students are engaging with weekly content unless they submit observations or responses that blatantly demonstrate a lack of understanding. Such instances are not rare and are certainly disheartening, but it is worth noting that the student tendencies of taking shortcuts and skimming are hardly problems unique to digital learning environments.

One of the most common critiques about digital learning is the high rate of attrition, estimated to be 93.5% for MOOCs such as Coursera (Jordan 2014). In this credit-bearing collaboration, we do not face this problem. If Global Scholars do not participate in the EdGE classroom, they will fail a course that appears on their FSU transcripts. But because it is a pass-fail course, our challenge is making sure that students are doing more than the bare minimum to pass.

Online Mentorship

EdGE Mentors are a crucial component of our effort to ensure that our online classroom is dialogical, reflexive, and personal. Our expectation that mentors provide thoughtful comments on each of their mentees’ weekly responses is the cornerstone of our strategy to ignite dialogue in the weekly forums. In ideal circumstances, every student’s weekly response will garner comments from his mentor and peers. In reality however, most but not all responses in any given weekly forum will spur this level of dialogue.

At the conclusion of the most recent Global Scholars session, we reviewed each mentor’s engagement with his or her mentees and provided substantial quantitative and qualitative feedback to each mentor. We analyzed mentor engagement and coded it according to seven possible categories: supportive, i.e. “This is a great post”; affirmative, i.e. “I liked when you said…”; follow-up, i.e. “How would you explain…?”; own opinion, i.e. “My perspective on this is…”; personal anecdote, i.e. “When I was in grad school…”; refer-to-material, i.e. “Freire would say…”; for-further-reading, i.e. “Check out this article about…”. This coding system allowed us to identify major trends in each mentor’s style of engagement. For example, one mentor’s evaluation reads that 93% of her comments were ‘supportive’ and ‘follow-up,’ while 40% were ‘affirmative’ and 7% were ‘own opinion.’ In addition, 27% of her comments resulted in a ‘back and forth’ (student responds to her comment at least once).

We believe our mentorship system is one of the most vital aspects of the EdGE program. It provides the personal touch that keeps students honest and involved. In the post-course evaluation mentioned earlier, all 23 respondents agreed that their mentor “makes himself/herself available to answer my questions”; 21 (91%) agreed that their mentor was “helpful” (two were neutral), and 20 (87%) agreed that their mentor “provided good comments on my weekly responses.” Nineteen (83%) Global Scholars agreed that mentorship was a “very valuable” aspect of EdGE and “plan to maintain communication with my mentor during and after my field position” (the remaining four were neutral to both questions).

V. Using Interactive Technology to Raise Critical Consciousness?

Interactive technology and service-learning are both on the rise within higher education, but there is little reason to assume that either will be a driver of social change rather than social reproduction. Despite the hype about egalitarianism and democratization that surrounds emergent digital learning platforms, we worry that the implementation and evaluation of such technologies are sometimes directed towards the goals of increasing efficiency and profit margins at the expense of student learning and transformation. Likewise, despite the buzzwords of global citizenship and collaborative partnerships that surround the proliferation of service-learning programs, we worry that many such programs lack substantive pedagogical vision and are oriented around placement models and paternalistic narratives that are intrinsically disempowering to those they purport to serve (Baillie Smith and Laurie 2011). The authors of this paper have sought to integrate the two trends of interactive technology and service-learning with the explicit aim of going beyond the buzzwords to cultivate critical inquiry and authentic collaboration in pursuit of social change. Our pedagogical vision derives from Freire’s notion of ‘raising critical consciousness’: a conviction that ‘knowing the world’ through dialogue and reflection is the first step towards creating change. The question, then, is whether or not such a vision can be actualized through an interactive digital platform—or at all.

It is surely too early to attempt any conclusive answer to this question, but the case study offered in this paper suggests that interactive technology might indeed be a useful tool for facilitating the sort of learning and collaboration that “critical service-learning” would seem to require. Further research should investigate not just what students are learning via the digital platform, but also how they translate this learning into their work on the ground while volunteering abroad and into the rest of their lives upon returning home.

Acknowledgements

Willy and Steve would like to thank the Omprakash EdGE Mentorship team, without which this article would not exist: Alex Frye, Eric Dietrich, Kalie Lasiter, Emily Hedin, Mayme Lefurgey, Miyuki Baker, Kit Dobyns, Shelby Rogala, Anabel Sanchez, Laura Stahnke, Matt Smith, Barclay Martin, Nathan Kennedy, Meredith Smith, Devi Lockwood, Nina Hall and Mary Jean Chan. W&S would also like to thank Lacey Worel for making sure the Omprakash trains run on time and Sonu Mahan and Adarsh Kumar for being brilliant web developers who can turn stale mockups into truly interactive technology. Finally, W&S would like to thank the other half of this great collaboration: Joe, Latika Young and Kim Reid. Joe would also like to thank Latika and Kim for making sure the FSU Global Scholars program runs so well.

Bibliography

Ausland, Aaron. 2010. Poverty Tourism Taxonomy 2.0. From <http://stayingfortea.org/2010/08/27/poverty-tourism-taxonomy-2-0/>. Accessed 31 May, 2014.

Baillie Smith, Matt, and Nina Laurie. 2011. “International volunteering and development: global citizenship and neoliberal professionalisation today.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 36 (4). OCLC 751323473.

Biddle, Pipa. 2013. The Problem with Little White Girls (and Boys): Why I Stopped Being a Voluntourist. From <http://pippabiddle.com/2014/02/18/the-problem-with-little-white-girls-and-boys/>. Accessed 31 May, 2014.

Citrin, David M. 2011. “Paul Farmer made me do it”: a qualitative study of short-term medical volunteer work in remote Nepal. Thesis (M.P.H.), University of Washington. OCLC 755939202.

Crabtree, Robbin D. 2008. “Theoretical Foundations for International Service-Learning.” Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning. 15 (1): 18-36. OCLC 425540415.

Crabtree, Robbin D. 2013. “The Intended and Unintended Consequences of International Service-Learning.” Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement. 17 (2): 43-66. OCLC 854574208.

Crossley E. 2012. “Poor but Happy: Volunteer Tourists’ Encounters with Poverty.” Tourism Geographies. 14 (2): 235-253. OCLC 792841012.

Dolnicar, S., and M. Randle. 2007. The international volunteering market: market segments and competitive relations. International Journal for Non-Profit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 12(4), 350-370. OCLC 826185553.

Finley, Ashley P., and Tia McNair. 2013. Assessing underserved students’ engagement in high-impact practices. OCLC 872625428.

Freire, Paulo. 1970. Pedagogy of the oppressed. [New York]: Herder and Herder. OCLC 103959.

Gacel-Avila, Jocelyne. 2005. “The Internationalisation of Higher Education: A Paradigm for Global Citizenry.” Journal of Studies in International Education 9 (2): 121-136. OCLC 424733796.

Green, Patrick, and Matthew Johnson, eds. 2014. Crossing Boundaries: Tensions and Transformation in international service-learning. Sterling, VA: Stylus. OCLC 877554267.

Harris, Suzy. 2008. “Internationalising the University.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 40 (2): 346-357. OCLC 4633544389.

Hartman, Eric, Richard C. Kiely, Jessica Friedrichs, and Judith V. Boettcher. 2013. Building a Better World The Pedagogy and Practice of Ethical Global Service Learning. Stylus Pub Llc. OCLC 866938358.

Hartman, Eric, Cody Morris Paris, and Brandon Blache-Cohen. 2012. “Tourism and transparency: navigating ethical risks in volunteerism with fair trade learning.” Africa Insight 42 (2): 157-168. OCLC 853073233.

Hartman, Eric, and Richard Kiely. 2014. “A Critical Global Citizenship.” In Green, Patrick, and Matthew Johnson. Crossing boundaries: tension and transformation in international service-learning. OCLC 877554267.

Hickel, Jason. 2013. “The ‘Real Experience’ industry: Student development projects and the depoliticisation of poverty.” Learning and Teaching 6 (2): 11-32. OCLC 5528846526.

Jones, A. 2005. Assessing international youth service programmes in two low income countries. Voluntary Action: The Journal of the Institute for Volunteering Research 7 (2): 87-100. OCLC 658807900.

Jordan, Katy. 2014. “Initial trends in enrolment and completion of massive open online courses.” The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning 15(1). OCLC 5602810303.

Leigh, R. 2011. State of the World’s Volunteerism Report. United Nations Development Programme. OCLC 779540815.

McBride, A., and Lough, B. 2010. “Access to International Volunteering.” Nonprofit Management & Leadership 21 (2): 195-208. OCLC 680823597.

Mintel. 2008. Volunteer Tourism – International. London: Mintel International Group Limited.

Mitchell, Tania D. 2008. “Traditional vs. Critical Service-Learning: Engaging the Literature to Differentiate Two Models.” Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning 14 (2): 50-65. OCLC 425540125.

Ouma, B., and H. Dimaras. 2013. “Views from the global south: exploring how student volunteers from the global north can achieve sustainable impact in global health.” Globalization and Health 9 (32): 1-6. OCLC 855505685.

Rieffel, L., and S. Zalud. 2006. International Volunteering: Smart Power. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution. OCLC 70134511.

Simpson, Kate. 2004. “‘Doing development’: the gap year, volunteer-tourists and a popular practice of development.” Journal of International Development 16 (5): 681-692. OCLC 5156622715.

Stein, N. 2012. “Is 2012 the year of the volunteer tourist?” From <http://www.travelmole.com/news_feature.php?news_id=1151074>. Accessed 31 May 2014.

Zakaria, Rafia. 2014. “The White Tourist’s Burden.” Al Jazeera, 21 April 2014.

[1] The neologism “voluntourism,” though lacking a precise definition, is generally used in a pejorative manner to describe programs that combine volunteering with tourism. Throughout this essay, we use the terms “service-learning,” “volunteering,” and “voluntourism” somewhat interchangeably—not because we are unaware that many commentators have attempted to delineate between them, but rather because we believe that such delineations often obscure more than they illuminate, and that our criticisms and suggestions are applicable to programs that fall into all of these categories as well as the grey area between them.

[2] To offer one example of the sort of high-cost “voluntourism” program against which we work to offer an alternative: an organization branding itself as “the gold standard of global engagement” sells ten-day trips to Uganda under the slogan of “short term trips; long term impact.” Customers pay a program fee of $1,990 plus airfare, and travel in groups of at least eight. In contrast, a student participating in Omprakash EdGE and working with an Omprakash partner in Uganda for sixty days would pay a total of roughly $1,350 plus airfare ($750 for the EdGE program fee, and $10 per day in country), and would receive pre-departure training and mentorship that is unavailable in the typical “voluntourism” model.

About the Authors

Willy Oppenheim is the founder and Executive Director of Omprakash, a web-based nonprofit that connects volunteers, interns and donors directly with social impact organizations in over 40 countries. Willy received a BA from Bowdoin College, where he completed a self-designed major in religion, education and anthropology. In 2009, he received a Rhodes Scholarship and is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in education from the University of Oxford. As an educator and educational researcher, Willy has worked in classrooms in the United States, India, Pakistan and China, and in the wilderness as an instructor for the National Outdoor Leadership School. For over 10 years, Willy has been working through Omprakash to transform the field of international service-learning to make it more affordable, more ethical, and more educational for everyone involved.

Joe O’Shea serves as the Director of Florida State University’s Center for Undergraduate Research and Academic Engagement and is an adjunct faculty member in the Department of Philosophy. He received a BA in philosophy and social science from Florida State University, where he served as the student body president and a university trustee. A Truman and Rhodes Scholar, he has a master’s degree in comparative social policy and a Ph.D. in education from the University of Oxford. Joe has been involved with developing education and health-care initiatives in communities in the United States and Sub-Saharan Africa. His research and publications are primarily focused on the civic and moral development of people, and his recent book, Gap Year: How Delaying College Changes People in Ways the World Needs, was published by Johns Hopkins University Press. Joe serves on the board of the American Gap Association and as an elected Councilor for the Council on Undergraduate Research, the leading national organization for the promotion of undergraduate research and scholarship.

Steve Sclar is the co-founder and Program Director for Omprakash EdGE (Education through Global Engagement). Steve received a BBA from the College of William & Mary, where he majored in Marketing and Environmental Science. He is finishing up an MPH in the Global Environmental Health department at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health. Previous volunteer or work experience in Tibet, Ghana and Iceland led Steve to his current role for Omprakash.