How the San of Southern Africa Used Digital Media as Educational and Political Tools

Philip Kreniske, The CUNY Graduate Center & Baruch College

Photography by Jesse Kipp, New York University

Abstract

The term San refers to the indigenous people of southern Africa, who for thousands of years lived a nomadic lifestyle, hunting and gathering for subsistence. Some contemporary San still subsist partially on food gathered from the bush. Many others have been pushed from their traditional lands and lifestyles and now struggle to subsist earning low wages in rural areas on the edges of cattle farms or urban areas working in factories and living on the fringes of informal settlements. In the past decade the San have begun to use new digital tools to document, communicate, and represent their values and struggles. This article focuses on how San people used digital technologies to generate educational texts by transcribing and web publishing traditional oral folktales and to inject their own perspectives into critical political debates. In each of these cases digital media enabled San people to realize explicit and implicit social and political agendas. This paper focuses on select digital representations of San people by San people and explores how these examples relate to larger issues of education and globalization in the region.

Introduction

Seminal scholarly work in the late 1950s portrayed the San people of Southern Africa as living the quintessential hunter-gatherer life—much as we might imagine our earliest ancestors to have done thousands of years ago. Today, there are about 100,000 San people, the majority of whom are spread across Namibia, Botswana and South Africa (Hays & Siegrühn 2005, 27). In each of these nations the San people have been economically, politically, and socially marginalized (Hays & Siegrühn 2005, 27; Hitchcock & Vinding 2004, 12-13, 19). Some contemporary San still live in remote villages throughout the Kalahari desert (Figure 1) and subsist partially on food gathered from the bush (Lee 2013, 218), while many others have been pushed from their traditional lands and lifestyles and now struggle to subsist earning low wages in rural areas on the edges of cattle farms or urban areas working in factories and living on the fringes of informal settlements (Susser 2009, 173).

Figure 1. A San Village in Nyae Nyae, Namibia

This article focuses on two ways that San people use digital technologies: first, to generate educational texts by transcribing and web publishing traditional oral folktales; and second, to inject their perspectives into political debates, as was the case when San bloggers wrote about issues of land rights and education. In each of these cases there were explicit and implicit social and political agendas that were realized through the use of narratives and digital media. Narrative is one of the oldest tools for sharing and creating knowledge (Bruner 1986, 3-44), and written narratives become physical manifestations of this knowledge. These works may indicate a new era of San activism in which San people create the educational agenda and write the historical narrative.

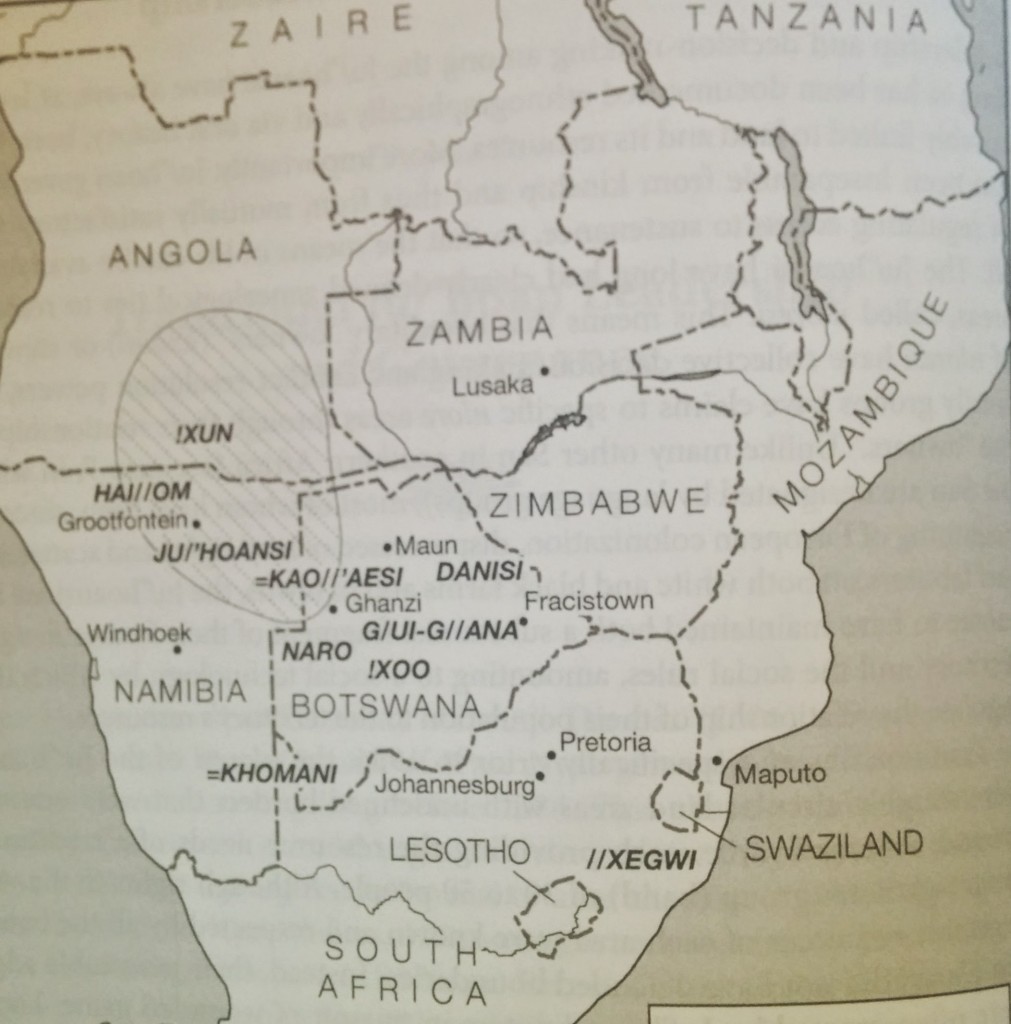

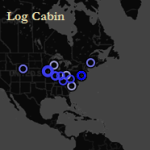

Historically the terms San, Khoisan, Bushmen, Basarwa, and Kwhe have all been used to refer to the diverse groups of indigenous southern African hunter-gatherers who speak related yet mutually unintelligible languages (Barnard 1992, 3-36; Suzman 2001a, 2, 55). Hitchcock, Ikeya, Biesele, and Lee (2006, 6) relate that at a meeting in Namibia in 1996, and reaffirmed at a meeting on Khoisan Identities and Cultural Heritage held in Cape Town in 1997, representatives of various San groups agreed that Khoisan be dropped in favor of two separate names, Khoe and San, and to allow the general term San to designate them externally. Furthermore, it was agreed that specific San group names, some of which are indicated in their general geographic region in Figure 2, should be employed for the various named social units (Hitchcock et al. 2006, 6). The current work focuses on the Ju|’hoansi in Namibia, the Naro in Botswana and the ǂKhomani in South Africa.

Figure 2. Map of San Groups by Region (Biesele and Hitchcock, 2011, p. 52).

The residual impact of apartheid policies in South Africa and Namibia, and more recent policies in Botswana, manifests in low literacy rates and, concurrently, few economic opportunities for the San people in these regions (Suzman 2001a, 9-13; WIMSA 2005, 2008). However, as will be explored in more detail below, the effects of such policies against the San differ vastly depending on their geo-political circumstances. For example, the Ju|’hoansi in the Nyae Nyae region live in a fairly expansive and isolated area. This isolation has made it difficult for contemporary San in the Nyae Nyae to earn a formal education, but historically this isolation has also served as a protective mechanism against the most culturally devastating aspects of the apartheid era, and more recently as a buffer against the AIDS epidemic (Susser 2009, 171-199).

The San in Namibia

The region currently known as Namibia earned its independence in 1990. From 1915 to 1990 the region, then called South-West Africa, was a mandate of South Africa and as such was subject to South Africa’s apartheid policies, which discriminated against all people of color, but were particularly pernicious for the San. For example, while other ethnic groups were allotted “homelands,” a series of policies that culminated with the Odendaal Commission’s recommendations in 1968 denied land rights to all but 2 percent of the San people in Namibia (Suzman 2001b, 85). Similarly, the San were largely excluded from formal economic and educational opportunities. In the mid-1990s Namibia began to address and remediate the impact of residual apartheid policies on the San people. In a watershed moment in 1997 at The National Workshop on African Languages in Basic Education, the Honorable Minister of Basic Education and Culture, John Mutorwa, publicly acknowledged:

In our country before Independence was achieved African languages were developed on a piecemeal basis. The result was that some languages received more attention than others and some were hardly developed at all. For example, one marginalized group of Namibian citizens, namely the Bushmen or San people, received so little attention that no education was available for them in any language except Afrikaans (cited in Brock-Utne 1997, 248).

For the San people in Namibia the legacy of these Apartheid policies persists to the present day. Namibia is a multi-cultural state with 13 recognized languages, ranking seventh among African nations with literacy rates of 91 and 94 percent for men and women respectively (UNICEF 2007). These high national literacy rates fail to capture the disparities within the nation, however. Demographics aggregated on an ethno-linguistic basis indicate the San[1] have the lowest life expectancy, the lowest income levels, and the lowest education rates in Namibia (UNDP 1998). According to the Working Group of Indigenous Minorities in Southern Africa (WIMSA) Report (2007-08), “this figure is so low that if the Namibian San were representative of the country as a whole, Namibia would rank between the Central African Republic and Sierra Leone at number 178 of the 180 countries ranked around the world” (13). Though Namibia may boast relatively high literacy rates, the San are a nation within a nation who by explicit or implicit policies have been denied the chance to secure an education.

The Digital Landscape in Nyae Nyae

In 1998 the Nyae Nyae conservancy was established as an autonomous San region within Namibia through the combined efforts of the government of Namibia and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). These organizations cooperated with consultants, development workers and local people.[2] Located in northeastern Namibia along the Botswana border, the Nyae Nyae Conservancy spans 250 km of the Kalahari Desert. The majority of San in the Nyae Nyae are Ju|’hoansi and they maintain a somewhat traditional lifestyle, living in numerous small villages dispersed across the area and subsisting on a combination of food gathered from the bush, store bought food, and government food subsidies (Lee 2013, 218). Traditionally huts were constructed of wood and thatch—though contemporary structures often use a variety of materials, for instance in Figure 3 a plastic tarp serves as a makeshift wall.

Figure 3. A San family home in Tsumkwe, Namibia.

A series of solar and wind powered boreholes dotted across the region provides the main water supply (Biesele and Hitchcock 2013, 10, 47; Hitchcock and Vinding 2004, 13) and few huts have electric power sources. In general, electrical power is scarce, and sources that can generate power in this type of remote region such as solar panels (Figure 4), windmills, vehicles and diesel generators are rarely available to the San (Biesele and Hitchcock 2013, 47; Lee 2013, xxii).

Figure 4. Rig-up of a battery to operate lights and recharge phones, powered by solar panel. This is at a remote location Apl-pos, a Ju|’hoan village 12 km. west of Tsumkwe. Photo from Richard Lee’s personal collection.

Until recently, even Tsumkwe, the largest village and the municipal center for the region, had power for only 10 hours a day. In 2012 this changed as the Desert Research Foundation completed the Tsumkwe Energy project, installing a solar diesel hybrid energy supply system that provided power to the village for 24 hours a day (“ACP EU Tsumkwe,” n.d.; “Tsumkwe Energy” 2012). In the center of Tsumkwe, there are a series of concrete government constructed houses (Figure 5), a community center, and a primary and secondary school. The first public computers were introduced in 2008, when the Namibian Ministry of Education, with support from the Namibia Association of Norway (NAMAS), established the Captain Kxao Kxami Community Centre in Tsumkwe (“News” 2009). This center served as a local library and was equipped with a few computers connected to the Internet, which was a major accomplishment (Susser 2009, 197). However, in my experience there in 2010, the connection was quite slow and it took the better part of an hour to send a single email. These remain the only computers connected to the Internet for public use in Nyae Nyae.

Figure 5. Young man sits outside row of concrete houses in center of Tsumkwe, Namibia.

How then can the San learn and engage with digital technologies? Despite technological obstacles, some San people have embraced the limited opportunities to work with digital technologies such as word processing and blogging, using these tools as a means of thinking through local debates and documenting political struggles often related to land rights. Specific developments such as improved infrastructure, the community center with public computers and Internet access, and an activist digital education project suggest a sea change.

The Ju|’hoansi Transcription Group (JTG)

In 2002, Megan Biesele, an anthropologist and community organizer who has been working in the region since the 1970s, organized one such educational opportunity (Biesele 2009, i-vii; Biesele and Hitchcock 2013). The project focused on transcribing the recordings of Ju|’hoansi folktales and political meetings that Biesele and others had been compiling for the last four decades. Over a ten-year period, Biesele worked with approximately twenty multi-lingual Ju|’hoansi from Nyae Nyae and surrounding areas. Using laptops donated by Sony and Redbush Tea Company and solar panels donated by BP (by 2006 consistent electricity was available in Tsumkwe and the solar panels were no longer necessary), the team transcribed the recordings into both written English and Ju|’hoansi.

One of the main goals of this project was to create culturally relevant curricula for Ju|’hoansi San learners (Biesele and Hitchcock 2013). A lack of relevant curricula has emerged as one issue that may contribute to the high attrition rate of San learners from the local schools (see Figure 6; Gabototwe 2011; Kreniske 2011). Gabototwe described how in his twelve years of schooling in Botswana he learned about King Shaka and Nelson Mandela, “but not once did a teacher mention past accounts of any San community.” Another goal, according to Biesele and Hitchcock (2013), was to combine the new technology of word processing, the transcription software Elan, and audio files with the “old” technology of collaborative learning that was traditional among the Ju|’hoansi and other San” (240). As part of the project, Biesele, along with three assistants, Catherine Collett, Taesun Moon and Victoria Goodman, helped the 22 San translators learn basic computer literacy skills.

Figure 6. Curricular materials for 8th and 10th grade respectively, Tsumkwe, Namibia.

Prior to this project there were no opportunities for San in the region to gain such computer skills. The participants were so motivated by the experience that over the course of the project the transcribers initiated a transcription group, in which they began to teach local San youth computer literacy skills. Biesele and Hitchcock detailed how upon learning of the project some of the most senior members of the community emerged from their more isolated villages and spent weeks helping the young transcribers decode aged audio files. The JTG bridged generations, creating a context of shared purpose where youth trainees, the relatively young transcribers, and the elderly members of the community generated a text that served as an archive of oral folktales and a useful tool for future Ju|’hoansi learners.

Culturally relevant texts are particularly useful for developing readers from underrepresented groups (Hale 2001, 111-152; Hillard 1992, 370-77; Lee 1995, 357-381; Lee 2012, 348-355). Students often struggle to connect and interpret traditional textbook materials that bear little relevance to their daily lives. The challenge becomes two-fold: a student must interpret the words and learn about the foreign context presented in the material. Relevant texts give learners the opportunity to call upon their semantic, procedural and conceptual understanding of the world, generally referred to as prior knowledge, to support their developing reading skills (Wolf 2008). For example, San students in Nyae Nyae have a rich understanding of the local flora and fauna. A text about local plants and animals would allow for these students to develop their reading skills while they draw on their past experiences and interpret the text. Considering the thirteen recognized languages in Namibia, providing each group of learners with culturally relevant materials is a great challenge. As noted earlier, the San are one group whose educational needs have been largely neglected. The compilation of Ju|’hoan folktales was created explicitly to meet this need, and is appropriately titled Ju|’haon Folktales: Transcriptions and English Translations: A Literacy Primer by and for Youth and Adults of the Ju|’hoan Community (Biesele 2009).

Furthermore, the compilation produced by the transcription project served as one of the few archival and historical records of Ju|’hoan folktales. The process of transcribing was an occasion for intergenerational communication, involving the development of young trainees’ computer literacy in collaboration with the elders’ unique language comprehension skills. In the print and web published text, traditional values of collaboration and practices of storytelling were integrated with digital literacy and community organizing to produce a tool for future educational and cultural purposes.

The published book itself is an impressive product, but perhaps the most important contribution of this community-based educational initiative was the intergenerational collaboration developed with and by the local participants and the genesis of a core group of skilled San people who continued to produce texts in varied digital and print media. At least one member of the JTG, Tsamkxao Fanni Cwi, continued working on Ju|’hoan – English translations. In collaboration with Kerry Jones, Cwi recently published the Ju|’hoan Children’s Picture Dictionary (2014), a culturally relevant text that Ju|’hoan can use to develop their literacy skills. The digital translation and word processing skills learned by these San people allowed them to take an active role in creating culturally relevant educational materials. In light of the years of exclusion from the educational system during the apartheid era, the creation of Ju|’hoansi educational texts stands as a major political statement and accomplishment. Both Fanni Cwi and another JTG member, Beesa Crystal Bo would also join the The Kalahari Peoples Network (KPN), a community-based educational initiative that grew into a rich tool for digital communication and community activism.

San Bloggers

Issues of San representation have long been a topic of academic interest and debate (Barnard, 2007; Hitchcock, et al. 2006, 1-7). In popular culture from films to websites the San people are typically exhibited in their traditional garb and in some cases even listed as attractions alongside exotic animals (Cooper 2013; “Extreme Namibia” 2013; “San in Kruger Park” n.d.; The Gods Must Be Crazy 1984). However, digital representations—like printed texts—authored by San people are scarce.

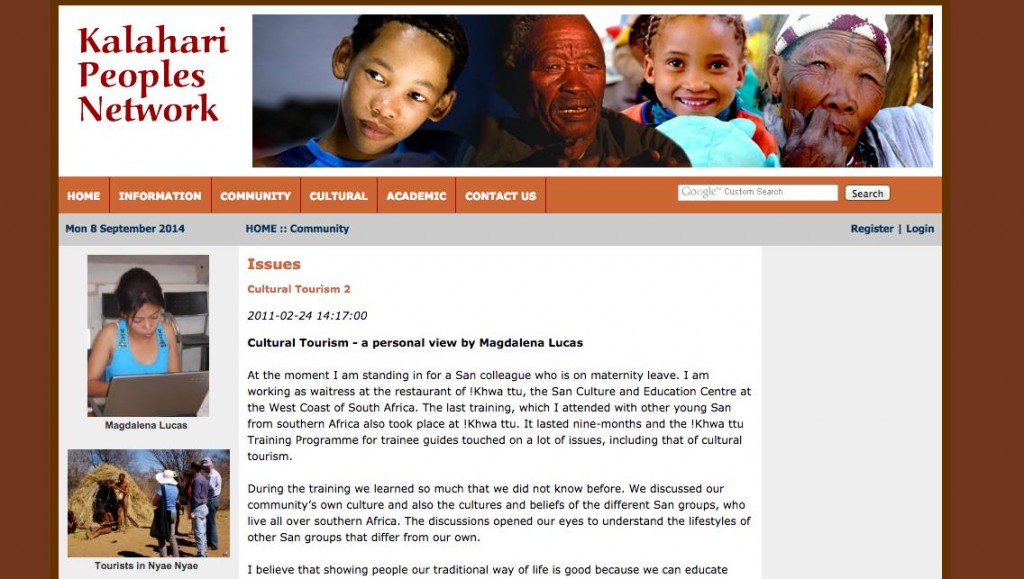

The KPN is a unique example of a site where San people wrote and posted their own perspectives on current issues and values. Founded in 2008 by a group of activists and academics affiliated with the Kalahari Peoples Fund (a small non-profit based in Austin, Texas and founded in the 1970’s), KPN’s mission was to provide a network for exchange of ideas and information between Kalahari communities and individuals across Southern Africa (“About” n.d.).

In 2011, KPN held a twelve-day course in !Khwa ttu, a San educational and cultural center near Cape Town. The word !Khwa ttu means water or water pan in the no longer spoken San language |Xam (Staehelin 2002). |Xam also provides the motto for the South African coat of arms, !ke e: /xarra//ke, literally meaning “diverse peoples unite” (Government Communication and Information System 2000; Figure 7). Interestingly, this motto might also be appropriate for !Khwa ttu and KPN, two organizations that worked to unify San people from across the region. Furthermore, both !Khwa ttu and KPN sought to empower San people with the technical skills to represent their own communities and values.

Figure 7. South African Coat of Arms.

Established through the combination of efforts by local San organizers and a small Swiss charitable organization, UBUNTU Foundation, !Khwa ttu’s mandate reads, “that we, the San, must gain control over our own image and presence in the tourism industry. We strive to acquire the skills for income generating activities and to be proactive in preventing exploitation of our less educated San relatives” (“Mission” n.d.). Considering that the San groups exist as disparate entities spread across southern Africa—many like the Ju|’hoansi in Nyae Nyae Namibia live in remote regions—this appears to be a weighty and possibly problematic task. For instance, it is unlikely that the Ju|’hoansi in Nyae Nyae Namibia would want the mainly ǂKhomani San in !Kwa ttu to intervene on their behalf. The KPN was founded in part to address such challenging issues and to develop a communication and support network run by San and for San people with representatives from a variety of groups.

The !Khwa ttu workshop and the subsequent KPN project sought to unite San from across the region and to serve as “a virtual space for networking and exchange of information among contemporary Kalahari communities and individuals…” and as a space for “San and other indigenous Kalahari dwellers to speak in their own voices to each other and to interested people outside their communities (“About” n.d.). As will be explored below, some of the KPN editors expanded their work beyond the San people, broadening their network and developing connections with international indigenous rights groups.

The immediate goal of the KPN training course was to identify and prepare ten San deputy editors from across the region (“Education” 2011). One editor, Jobe Gabototwe, would later blog about this formative experience, writing:

As a young boy growing up in the small village of Kedia in central Botswana I believed that my people, the San (also known as Basarwa or Bushmen) were only to be found in my country. All people coming from Namibia, I, and all around me, used to address as ‘Hereros.’ I was proven wrong when I enrolled in the !Khwa ttu Training Programme for Trainee Guides (2011).

Gabototwe noted that the attendees were San from different cultural, linguistic, and geographic regions including South Africa, Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Namibia.

A narrative analysis approach based on the methods of values analysis (Daiute 2004,111-135; Daiute 2014, 68-113; Ninkovic 2012) was used to examine over 30 blog posts written by two San deputy editors and consistent contributors, Magdelena Lucas and Job Morris. A values analysis is useful for exploring how narrators position themselves in relation to particular contexts. For example, Lucas often used her posts to express the value that earning an education was important especially for San people. Lucas’s position directly contests the position communicated by the apartheid state that expressed its values that education was not important for the San people through a series of discriminatory legislation. The analysis—explored in detail below—showed how Lucas and Morris used their blog posts to expound on the value of education and debate issues such as the displacement of San people and the uses of cultural tourism in their communities.

Both deputy editors wrote about their own life journeys and academic accomplishments. However, their emphases differed. While Lucas frequently described the personal importance of specific internships and educational accomplishments, Morris more often wrestled with issues of San leadership and the San peoples’ struggles with local and global interests and powers. Through their writing, these two San bloggers struggled to make sense of how they and their communities fit into the changing local and global context. Literary theorists (Berthoff & Stephens 1988; Emig 1977, 122-128; Fulwiler 1983, 122-133) and social scientists have shown how the act of writing is a tool for sense-making (Daiute & Nelson 1997, 207-216; Lucic 2013, 434-439). Sense-making often involves asking questions and working through complex dilemmas. For example, both Morris and Lucas used their writing to explore the positive and negative effects of cultural tourism for the San people. Through writing about this question, each blogger formulated a clearer position on the role they thought cultural tourism should play in their respective communities.

One way to make sense of questions is to talk about them. However, the spoken word is evanescent, while written words are thoughts manifested in physical space (Ong [1982] 2002, 77-114)—on paper or on a computer screen, or, if posted on the Internet, possibly on many screens. As compared to oral communication, reading the words in physical form, and therefore thinking about what one has written, makes the act of writing a distinct tool for sense-making. Writing requires high levels of cognitive and emotional effort, and it is in this process of sorting out how best to explain a set of thoughts or emotions to a specific audience that sense-making occurs. Furthermore, writing in an interactive medium like a blog allows for an active audience and such interaction has been shown to motivate writers (Boniel-Nissim & Barak 2011,333-341; Ducate & Lomicka 2008, 9-28; Sosnowy 2013, 80-86). Lucas and Morris were likely motivated by the potential to interact with a diverse audience as they used the blog to hone their positions and to simultaneously draw attention to key social, political and historical issues in their communities.

Their writings reflect both the similarities shared across San groups and also the different struggles each group faced. Lucas, a ǂKhomani, was born in Ashkam, a town in South Africa near the Botswana-Namibia border. For Lucas, education was of central importance and she demonstrated this by focusing her posts on telling the story of her own journey in contrast to that of her father’s experience during the apartheid regime. Whereas, Morris, a Naro from Botswana, blogged about issues of land rights focusing on large-scale displacement policies that have affected the San in Botswana for the past twenty years.

The history and current circumstances of the ǂKhomani San are quite different from those of the Ju|’hoansi in Nyae Nyae, who still speak their native language and subsist at least partially from food gathered from the bush. Lucas wrote that she learned Afrikaans as a first language and never learned her ancestral San language, N/u, because “farmers and old governments took our land and forbade us to use our own language” (Lucas 2011a, Figure 8).

Figure 8. Screenshot of “Cultural Tourism – a Personal View” By Magdalena Lucas.

The story of Lucas and her father reflects that of many ǂKhomani in South Africa who were kept from learning their native language and often denied the opportunity to attend formal schooling. These policies were so destructive that there are no surviving speakers of the N/u language (Barnard 1992, 88-90). In 1994, South Africa earned independence from the white minority, as voters in the first non-racial democratic elections selected the African National Congress (ANC) as the nation’s governing party. Although no San languages were included in the 11 official languages of South Africa, this massive political shift allowed for young San people, like Lucas, to be the first in their families to attend school and earn an education. Furthermore, initiatives such as those by KPN and the project at the resources center at !Khwa ttu provided Lucas with additional support as she developed her intellectual and technical skills.

To fully appreciate the importance of Lucas’s posts we need to consider not only the history of apartheid in southern Africa but also the continuing marginalization that the San people across the region endure (Suzman 2001b, 7-18, 38-40). Lucas’s (2010) story about her educational journey serves as an example of San resiliency in spite of a history of exclusion from formal educational institutions. Lucas described growing up with an alcoholic father who worked on a local “white” farm and a mother who valued education. Despite struggling to find basic necessities, Lucas persevered and graduated from grade 12. The post then shifts to the present, with Lucas expressing her excitement about being accepted into a nine-month training course at !Khwa ttu where she hoped to “learn about the past and the present of all the San groups that live in southern Africa.” In the final sentence of her post, Lucas wrote that she wanted “to use the knowledge and experience that she gained from the training wherever she will be lucky to get a job.” For Lucas, it was most important that this training lead to a job.

Over the nine-month tour guide training course Lucas posted about her experiences at !Khwa ttu and she also posted about the two-week Kalahari Peoples Network training mentioned above. In part through the connections and skills developed in these trainings Lucas landed a museum curator internship with Iziko Museums in Cape Town (Newsflash 2011-12). Following nearly two years of these trainings and internships, Lucas found herself again unemployed. Interestingly, she did not forsake the importance of education, but instead wrote a post titled Education is Power (2011b). In this post, Lucas initially acknowledged some of the financial obstacles stopping many San from enrolling in educational programs. She then launched into a detailed account of how her community had been battling for a civic project to install electricity and housing:

We also need educated San people to speak out for our rights as South African citizens; For example, we don’t have electricity on our farm. The people of Andriesvale in the southern Kalahari, where a lot of ǂKhomani families live, have told the municipality that they want houses. However, each year the municipality postpones the construction of houses. Each year, the government has given money for development but nothing has happened in our community. The community members wanted to know where the money went. Well, the municipality told us that it went back where it came from (Lucas 2011b).

In this statement, Lucas argued that had there been more educated community members they could have articulated the town’s position and this project would not have been abandoned. “Yes,” she continued, “We are living far away in the Kalahari but that doesn’t mean that the world can ignore us. We need our own lawyers, teachers and our representatives at the municipalities. It’s about time that we, the San take on challenges and change our circumstances.” Lucas described how the lack of advocacy allowed the local government to ignore the needs of her community. She understood that for this public project to recommence there needed to be educated San people who could fight the legal battles and voice their position at the municipal level.

Many of the barriers to San securing an education are related to decades of systematic oppression. There are also tensions between the San people’s traditional lifestyle and the current logistical realities of schooling. Lucas, for example, described spending much of her childhood living in a dormitory near the Ashkam primary school and then moving 90km further away to her secondary school in Rietfontein. Lucas’s story highlights the differences between her context and that of other San groups like the Ju|’hoansi in Nyae Nyae, Namibia. In Nyae Nyae, tensions between traditional lifestyles and the logistical demands of schooling are even more pronounced. Limited transportation is an issue of critical concern to many local residents (Hays 2002, 132; Kreniske 2011).

Many villages can only be reached using four-wheel drive vehicles, as throughout the Nyae Nyae only a few roads are paved and there is no formal public transportation system. Hardly any San have access to vehicles and therefore hitchhiking and walking are the only options. These circumstances are challenging enough for an average adult, but for a child traveling hundreds of kilometers from their village to their school, the lack of transport is often an insurmountable obstacle. These obstacles force children to choose between living with their families and boarding at school. Researchers have documented some of the struggles that San people face in earning an education (Biesele & Hitchcock 2013, 233-44; Kreniske 2011; Hays 2002, 123-139). However, Lucas’s posts present a first-hand account of the struggles that many San face as they attempt to earn a formal education.

Perhaps Lucas could and would have written about these issues in print. However, there is something special about writing in digital media and specifically posting on the Internet that inspires individuals to inject themselves into public debates, as Yochai Benkler has argued. According to Benkler:

Individuals become less passive, and thus more engaged observers of social spaces that could potentially become subjects for political conversation; they become more engaged participants in the debates about their observations. The various formats of the networked public sphere provide anyone with an outlet to speak, to inquire, to investigate, without need to access the resources of a major media organization (Benkler 2006, 11).

For Lucas the outlet was the KPN blog, and her posts about earning an education functioned as social and political acts. The KPN blog provided a medium for Lucas to enter a conversation that has long revolved around San peoples’ inability to earn an education that rarely included San voices. Her story provides a narrative that counters this negative perception of the San. With her posts Lucas makes a political statement and shows how San can succeed within the current educational system in spite of the many obstacles they may face.

Morris, a Naro San who grew up in D’Kar Botswana, also used his blog posts to engage in social and political debates. In one post, Morris directly addressed cultural tourism by weighing the pros and cons of practices such as dressing in traditional garb and showing tourists the traditional way of life (2011a). Morris argued that in some ways cultural tourism encouraged San people to remember their traditional ways and counter what he described as “cultural pollution,” which occurs when San people adopt a “foreign/western way of life” (Morris 2011a, Figure 9). However, he noted the economic returns from cultural tourism were minimal. Further, Morris explained that the problem with cultural tourism was that it distracts young people from pursuing other potentially rewarding career paths. He wrote that cultural tourism “diverts the young people from school and distracts them from a better future. It creates only seasonal means of employment and has no job security, no health care, low benefits and no protective organization.” Morris worried that cultural tourism too often exploited the San—promising only minor compensation and few broader benefits. Morris explained that the San still value and respect their traditional culture, but that they “do not live a traditional lifestyle on a daily basis.”

Figure 9. Screenshot of “Cultural Tourism – Good or Bad?” By Job Morris.

A related post by Morris revolved around destruction of the environment and the displacement of the San from their traditional lands. Morris wrote: “Mother Earth is a source of life for the San and their very existence as a people is embedded in how they survive in that land…[and] for other people to take away their precious land is more like killing the San.”

This statement may appear to be figurative, however according to Lee (2013, 218) it is literally true. Lee described how contemporary San in the Nyae Nyae still forage nearly half of their sustenance from the Kalahari, and that without these natural sources many San would live in complete destitution, facing near starvation. In his post, Morris also connected the figurative and emotional with the practical uses of the land by describing the practice of foraging for tubers. After digging up a tuber the San rebury the root so the tuber can grow again “and be a resource to others as well.” Morris used this post to illustrate one way that contemporary San still subsist on foods foraged from the bush using traditional practices.

Given the continued importance of foraging for food, a critical struggle for many San groups across the region, from the early twentieth century to the present moment, concerns challenges to their land rights. At times these challenges arrived in the form of military force (Suzman, 2001a), political mandates (“Bushmen” n.d.), or in a less dramatic, but still destructive guise, as cattle herding squatters (Odendaal 2013). Morris used a number of blog posts to call for regional leadership structures that he and his fellow San could organize with the goal of securing San land rights in Southern Africa. One similar value shared across many San groups is an egalitarian—and to an outsider enigmatic—leadership system (Lee 2013, 121-124). Morris described this leadership system as “everyone can lead but not anyone can lead” (2012a). He then described his experiences with leadership and the decision making process. A leader:

[…] invites his people around the fire and they establish dialogue about the matters that have aroused in the clan/community. Around the fire, the leader invites his people to talk about the things that should be done and it is where healing takes place. He invites them to touch upon their joys and sorrows and around the fire, they tell stories. These are the folklores or tails that have been passed on to them by the generations before them and they can be seen on the rock art that has existed through many lifetimes.

This post illustrates the tensions between the similarities and the distinct cultural practices of different San groups. Morris is attempting to marshal the images of rock art to support a narrative of unified San identity. Notably, only the San of South Africa have a history of creating rock art. As Morris described, many San groups did traditionally use similar leadership systems that emphasized egalitarian community-based discussions and decision-making that some scholars have referred to as direct democracy (Biesele & Hitchcock 2013). With this and other posts Morris attempted to amalgamate the San people into a unified political force. For Morris, the project of a unified San identity extended well beyond the proverbial campfire.

Morris’s posts reflected the work he was doing to actively share the story of the San people in international forums. Morris seemed to understand the power of presenting a unified San identity as he attempted to organize regional leadership and develop connections with international indigenous rights activists. In D’Kar, Morris collaborated primarily with the Kuru Family of Organizations which supported him as he blogged and submitted proposals to international conferences. In 2011, Morris presented the case of the San of Botswana to the 10th United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) in New York. Morris used the forum and his subsequent blog post to focus on issues of forceful relocation in Botswana, writing:

Numerous San communities were relocated from their Ancestral Lands as in the recent CKGR (Central Kalahari Game Reserve) case. Some San were forced to move in the name of Development and some died in the name of development. There in CKGR, because of the forced relocation, their livelihood, culture and values are slowly diminishing. They have a small land for a vast number of people. (2011b)

Morris then called attention to Botswana’s refusal to ratify ILO Convention 169, which would officially eliminate the colonialist doctrine of discovery (Lee 2012), and in the words of Morris, “give us our right to own land that we have traditionally occupied from time immemorial and protect our languages, cultures, and heritage. This to us is development” (2011b). Lucas and Morris both envisioned educated San voicing their respective struggles in local and international forums. With his speech at the UN, Morris took a leadership role on a global stage for the rights of San people and also for indigenous people across the globe. Morris concluded by calling on other “indigenous Peoples who have made it” to “empower us, show us, guide us, strengthen us, motivate us and increase our capacities based on your experiences so that we can become more than just how other societies perceive us, but also people who are sustainable and independent.” As Morris delivered this closing statement he seemed acutely aware of the international audience of indigenous people and activists. Sharing the story of the San, and specifically those who were relocated from the CKGR in Botswana, certainly drew international attention to issues of San land rights. Gaining this attention was the product of efforts by Morris and by Kuru and others who supported him along his journey.

However, there was an inherent tension between Morris’s depiction of the campfire community meeting and his solo presentation at the UN. Where in his speech was there room for egalitarian discussion that he previously noted as a key characteristic of San decision-making and leadership? In theory the KPN was founded in an attempt to create a network for San people and activists throughout southern Africa to communicate. Morris’s posts on the KPN blog had the potential to function as a space for discussion, with interested San people from across the region commenting on his ideas for action or perhaps contributing to, or even editing the script for his speech.

Despite his prolific posting and international speeches, Morris received few comments on his posts, and the comments he did receive were rarely written by fellow San. One reply to Morris’s UN address was posted by Eugene Skeef, a South African born percussionist and activist residing in the UK since the 1980s, who wrote, “Thanks for a very moving account. We all need to pull together to realize the vision of your statement.”[3] In general, comments on the KPN site were limited, with Morris and Jobe Gabototwe being the most active commenters—often adding positive comments to fellow bloggers’ posts.

Based on the mission statement, the intended audience of the KPN blog was other San people, academics, activists, and policymakers interested in indigenous issues. Likely reasons for the lack of comments from other San people include the aforementioned relative isolation of many San communities, combined with the lack of material means such as computers and reliable Internet connections. Additionally, the long history of exclusion from traditional educational systems and resulting low literacy rates precluded many San people from participating in any written media.

Another possible factor leading to the low number of comments on the KPN was that the blog required users to login or register to leave a comment. No doubt this login requirement was intended to limit advertisers and other web crawlers who take advantage of many blogs’ comment sections as a space to promote unrelated products and sites. In my experience as an administrator for a number of blogs, the majority of comments are often from advertisers, and legitimate comments are relatively rare. Requiring a login can discourage the aforementioned ne’er-do-wells but may also limit contributions from potential casual commenters and less savvy Internet users. While academics and activists posted some comments, there were no comments posted by San people, aside from the comments posted by San deputy editors like Morris, Lucas, and Gabototwe. The lack of comments makes it difficult to determine who was in fact reading the KPN blog.[4] Despite the few comments, or the larger question of determining who reads what on any particular website, the content produced on KPN remains a valuable resource for academics, activists, and policymakers.

Over the two years that Morris and Lucas posted on KPN, they, along with the other deputy editors, created a rich database of folk stories, testimonials, and archival records both for San people and by San people. The act of blogging may have encouraged them to “observe the social environments through new eyes—the eyes of someone who could actually inject a thought, a criticism, or a concern into the public debate” (Benkler 2006, 11). Using their blog posts, Lucas and Morris worked through challenging issues and formulated critical positions on controversial topics such as the value of and access to an education, the pros and cons of cultural tourism, and the large-scale displacement of San peoples in Botswana. At least in part, it was through his blogging that Morris nurtured his leadership skills and honed the positions that he would eventually present at the United Nations. But even before Morris arrived at the UN, his words could reach activists across the globe. Writing online made the KPN bloggers’ work accessible to anyone with an Internet connection. As Daiute (2013) notes, “the digital world makes conflicts, inequalities, and abuses worldwide visible to all with access not only to personal computers but also to public displays, news and conversation” (65). These bloggers created an active network for documenting their experiences and critiquing the policies of the regional states.

The site remains a rich resource featuring opinions from San people depicting their understanding of local and global issues, although in 2012 KPN’s funding dried up and the site is presently an inactive archive. If we understand blogging as a key aspect of Lucas’s and Morris’s development as community activists and global advocates, then it seems imperative to continue to support San bloggers. KPF, the agency that founded KPN, remains open to donations for similar initiatives. One such initiative could be to follow Morris’s recommendation and work with San people to establish a sustainable and independent site where San people could continue to develop as activists while sharing their struggles and triumphs in coordinating future projects.

Concluding Thoughts

The Kalahari is a harsh environment for humans to live: water is scarce; nubby plants dot a sandy landscape that seems to extend for infinity; animals—some of them large and dangerous—migrate over great distances; while the temperature fluctuates from freezing at night to sweltering during the day. In spite of these apparent ecological challenges, the San people, using their expansive knowledge of the environment, have thrived on this land for thousands of years. In recent decades, the increasing interconnectedness of the global and the local, in part due to technological advances, has presented new challenges and opportunities for the San. Like many across the globe, the San have begun to use new digital tools to document, communicate, and represent their values and struggles.

In Nyae Nyae, the Ju|’hoansi Transcription Group created one of the first published works of San folktales. In this project, the San combined the traditional practice of storytelling with computer literacy and transcribing tools. The project bridged generational gaps as older community members were called in to help decipher some of the recordings and younger San became apprentices to the trained transcribers—learning basic computer literacy skills along the way. The digital tools enabled a grass roots team of linguists and locals to create a desperately needed culturally relevant text. The book, also published on the web, is not only an archive of stories that might otherwise have been lost to future generations, but also a relevant pedagogical tool that can be leveraged to support developing Ju|’hoansi readers. The work illustrates a growing sense of the value of education for and within the Ju|’hoansi community.

Similarly, the KPN blog was often used as a forum to discuss the impediments to, and to tout the importance of earning an education for San people across the region. The blog was also a space for the deputy editors to work through concepts of leadership and articulate their perspectives on community issues, such as the struggles against international diamond corporations which, with the help of the government of Botswana, pushed many San from their lands. After years of legal battles the San have begun to return to their lands in Botswana, but this conflict is far from resolved, nor are such conflicts isolated to Botswana. In 2010 in Namibia, Herero crossed the border from Botswana and settled on San owned lands in Nyae Nyae Conservancy (Biesele 2010). In part because the local San have little political influence, they have not been able to extradite these illegal squatters who strain the areas’ already limited water, land, and educational resources. By using digital tools, like the KPN blog, in combination with speeches at international conferences and legal battles at home, the San have been able to push back and gain some recognition of their land rights.

Facilitated by digital tools, the transcription group created culturally relevant texts and the San bloggers developed critical social and political commentary. However, it remains to be seen what the lasting effects of these projects will be. A series of questions remain unanswered: Will the Ju|’hoan Children’s dictionary be the last work translated, or will it be just the second in a litany of educational texts? Does the lack of comments on the KPN blog by other San mean that the work of the KPN bloggers went largely unnoticed? Or does the number of comments written by the KPN deputy editors indicate that San people—when they can get access—will embrace digital tools and use them to develop cohesive inter and intra group activist networks? What is known is that these works suggest a great potential for the uses of digital technology by underrepresented peoples, and stand as rare examples of texts—digital or print—about San, by San, and for the San. Especially for people like the San who have been represented and misrepresented in innumerable ways, writing about their values and struggles is a political act, and the San bloggers used their posts to construct a powerful new narrative for the San of the modern era.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Richard Lee and Megan Biesele for their support in the field and their comments on the manuscript.

Bibliography

Barnard, Alan. 1992. Hunters and Herders of Southern Africa: A Comparative Ethnography of the Khoisan Peoples. New York: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 842642433.

Barnard, Alan. 2007. Anthropology and the Bushman. Oxford: Berg. OCLC 560526388.

Benkler, Yochai. 2006. The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom. New Haven: Yale University Press. OCLC 61881089.

Berthoff, Ann E., and James Stephens. 1988. Forming, Thinking, Writing. Portsmouth: Boynton/Cook Publishers. OCLC 17983445.

Bruner, Jerome. 1986. Actual Minds, Possible Worlds. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. OCLC 12946633.

Biesele, Megan. 2009. Ju|’hoan folktales: transcriptions and English translations: A Literacy Primer by and for the Youth and Adults of the Ju|’hoan community. Bloomington, Indiana: Trafford Pub. OCLC 515127452.

Biesele, Megan. 2010, November. San Leadership in Nyae Nyae, Namibia, and the Pastoral Invasions of 1991 and 2009. Paper presented at the meeting of American Anthropological Association, New Orleans, LA.

Biesele, Megan, and Robert K. Hitchcock. 2013. The Ju|’hoan San of Nyae Nyae and Namibian Independence: Development, Democracy, and Indigenous Voices in Southern Africa. New York: Berghahn Books. OCLC 609529125.

Boniel-Nissim, Meyran, and Azy Barak. 2013. “The Therapeutic Value of Adolescents’ Blogging About Social–Emotional Difficulties.” Psychological Services. 10 (3): 333-341. OCLC 4815019024.

Brock-Utne, Birgit. 1997. “The Language Question in Namibian Schools”. International Review of Education/Internationale Zeitschrift Fuer Erziehungswissenschaft/Revue Internationale De L’Education. 43 (2-3): 241-60. ISSN 0020-8566.

Cooper, Chloe. 2013. “A Kalahari Bushman Experience at Haina Lodge.” Africa Geographic (blog). http://blog.africageographic.com/africa-geographic-blog/people/a-kalahari-bushmen-experience-at-haina-lodge/ (accessed March 15, 2014).

Cwi, T. F. and K.L. Jones, 2014. Ju|’hoan Children’s Picture Dictionary: Tsumkwe Dialect. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press. OCLC 871319304.

Daiute, Colette. 2004. “Creative use of Cultural Genres.” In C. Daiute & C. Lightfoot (Eds.) Narrative Analysis: Studying the Development of Individuals in Society, 111 – 135. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. OCLC 52559098.

Ibid. 2013. “Educational Uses of the Digital World for Human Development.” Learning Landscapes. 6(2): 63-83.

Ibid. (2014). Narrative Inquiry: A Dynamic Approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. OCLC 835373980.

Daiute, Colette, and Katherine Nelson. 1997. “Making Sense of the Sense-Making Function of Narrative Evaluation.” Journal of Narrative and Life History. 7 (1/4): 207-216. OCLC 200360718.

Desert Research Foundation of Namibia. “ACP EU Tsumkwe Energy.” http://drfn.org.na/projects/energy/tsumkwe/ (accessed October 10, 2014).

Ducate, Lara C., and Lara L. Lomicka. 2008. “Adventures in the Blogosphere: from Blog Readers to Blog Writers.” Computer Assisted Language Learning. 21 (1): 9-28. OCLC 4901605147.

Emig, Janet. 1977. Writing as a Mode of Learning. College Composition and Communication. 28 (2): 122-128. OCLC 425033720.

Gabototwe, Jobe. 2011. “The |Xam and the San youth of today.” Kalahari Peoples Network (blog). http://www.kalaharipeoples.net/article.php?i=307&c=8 (accessed August 28, 2014).

Hale, Janice E. 2001. Learning While Black: Creating Educational Excellence for African American Children, 111-152. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. OCLC 45821018.

Lee, Richard B. 2013. The Dobe Ju|’hoansi. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. OCLC 801223566.

Fulwiler, Toby. 1983. “Why We Teach Writing in the First Place.” fforum.4(2): 122-133. Retrieved from http://comppile.org/archives/fforum/fforum4(2).htm (accessed 9/18/2014).

Hathaway, Jay. 2014. “NPR Pulled a Brilliant April Fools’ Prank On People Who Don’t Read.” Gawker. http://gawker.com/npr-pulled-a-brilliant-april-fools-prank-on-people-who-1557745710 (accessed April 4, 2014).

Government Communications and Information System. 2000. “The National Coat of Arms.” South African National Symbols and Heritage. http://www.sahistory.org.za/national-coat-arms (Accessed August 22, 2014)

Hays, Jennifer. 2002. “‘We should learn as we go ahead’: Finding the way forward for Nyae Nyae Village Schools Project.” Perspectives in Education, 20 (1): 123-139. OCLC 775995239.

Hays, Jennifer, and Amanda Siegrühn. 2005. “Education and the San of Southern Africa.” Indigenous Affairs. (1): 26-34. OCLC 775150286.

Hilliard, Asa G., III. 1992. “Behavioral Style, Culture, and Teaching and Learning.” Journal of Negro Education. 61 (3): 370-77. OCLC 425478076.

Hitchcock, Robert K., and Diana Vinding. 2004. Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in Southern Africa. Copenhagen: IWGIA. OCLC 57255814.

Kalahari Peoples Network. “About the Site.” http://www.kalaharipeoples.net/about.php (accessed February 12, 2014).

Ibid. 2011. “Education: Kalahari Peoples Network Workshop.” http://www.kalaharipeoples.net/article.php?i=301&c=26 (accessed February 12, 2014).

Kreniske, Philip. 2011. “Education in Nyae Nyae.” Kalahari Peoples Network (blog). http://www.kalaharipeoples.net/article.php?i=278&c=26 (accessed March 1, 2014).

Kruger Park. “San.” http://www.krugerpark.co.za/africa_bushmen.html (accessed March 1, 2014).

ǂ Khomani San. “History of the San.” http://www.khomanisan.com/about-us/ (accessed March 3, 2014).

!Khwa ttu. “Newsflash: Summer 2011/12.” http://www.khwattu.org/engage/newsletter/dec-and-jan-2011-2012/?id=109 (accessed March 10, 2014).

Lee, Carol D. 1995. “Signifying as a Scaffold for Literary Interpretation.” Journal of Black Psychology. 21 (4): 357-381. OCLC 197886943.

Ibid. 2012. “Conceptualizing Cultural and Racialized Process in Learning.” Human Development. 55 (5-6): 348-355. OCLC 4939164484.

Lee, Richard B. 2013. The Dobe Ju|’hoansi, Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. OCLC 801223566.

Ibid. 2012. “Historic day for the San.” The Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa. http://www.osisa.org/indigenous-peoples/regional/historic-day-san (accessed March 5, 2014).

Lee, Richard, B., Robert Hitchcock and Megan Biesele. 2002. “Foragers to First Peoples: The Kalahari San Today.” Cultural Survival Quarterly 26.1.

Lucas, Magdalena. 2010. “New Writing: Life is Worth Living…” Kalahari Peoples Network (blog). http://www.kalaharipeoples.net/article.php?i=201&c=10 (accessed March 15, 2014).

Ibid. 2011a. “Cultural Tourism – a Personal View.” Kalahari Peoples Network (blog). http://www.kalaharipeoples.net/article.php?i=276&c=8 (accessed March 15, 2014).

Ibid. 2011b. “Education is Power.” Kalahari Peoples Network (blog). http://www.kalaharipeoples.net/article.php?i=292&c=8 (accessed March 15, 2014).

Lucić, Luka. 2013. “Use of evaluative devices by youth for sense-making of culturally diverse interpersonal interactions”. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 37 (4): 434-449. OCLC 5108856615.

Morris, Job. 2011a. “Cultural Tourism—good or bad?.” Kalahari Peoples Network (blog). http://www.kalaharipeoples.net/article.php?i=275&c=8 (accessed March 15, 2014).

Ibid. 2011b. “Statement of San issues at UN.” Kalahari Peoples Network (blog). http://www.kalaharipeoples.net/article.php?i=290&c=8 (accessed March 15, 2014).

Ibid. 2012. “Leadership of the San.” Kalahari Peoples Network (blog). http://www.kalaharipeoples.net/article.php?i=355&c=8 (accessed March 15, 2014).

News. “News: Captain Kxao Kxami Community Centre, Tsumkwe”. August, 2009. http://www.kalaharipeoples.net/article.php?i=139&c=6 (accessed August 27, 2014).

Namibia Tourism Board. “Extreme Namibia—The World’s First People.” http://stories.namibiatourism.com.na/blog/bid/266317/EXTREME-NAMIBIA-The-World-s-First-People (accessed March 15, 2014).

Ninkovic, M. 2012. Changing the Subject: Human Resource Management in Post

Socialist Workplaces. PhD Diss. The Graduate Center, City University of New York.

Odendaal, Willems. 2013. “Land Laws Failing the San.” The Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa. http://www.osisa.org/fr/indigenous-peoples/blog/land-laws-failing-san (accessed March 5, 2014).

Ong, Walter J. [1982] 2002. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. London: Routledge. OCLC 49874897.

Simpson, John. 2011. “The Kalahari Bushmen are Home Again.” The Guardian, December 13. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2011/dec/13/kalahari-bushmen-home-again-botswana-diamonds (accessed March 15, 2014).

Sosnowy, Collette. 2013. Blogging Chronic Illness and Negotiating Patient-hood: Online Narratives of Women with MS. PhD diss. Graduate Center, City University of New York. OCLC 868831972.

Staehelin, Irene. 2002. “!Khwa ttu: San Culture & Education Centre.” Cultural Survival Quarterly, Spring. https://www.culturalsurvival.org/ourpublications/csq/article/khwa-ttu-san-culture-education-centre (accessed August 22, 2014).

Susser, Ida. 2009. AIDS, Sex, and Culture: Global Politics and Survival in Southern Africa. Chichester, West Sussex, U.K.: Wiley-Blackwell. OCLC 244598965.

Survival International. “Bushmen.” http://www.survivalinternational.org/tribes/bushmen (accessed February 27, 2014).

Suzman, James. 2001a. Regional Assessment of the Status of the San in Southern Africa. Windhoek: Legal Assistance Centre, Report no. 1. OCLC 50630191.

Ibid. 2001b. Regional Assessment of the Status of the San in Southern Africa. Windhoek: Legal Assistance Centre, Report no. 5. OCLC 50630191.

Tsumkwe Energy Project. 2012. “Tsunkwe Energy.” http://www.tsumkweenergy.org/overview/ (accessed October 3, 2014).

UNICEF. 2009. The State of the World’s Children: Special Edition. New York, NY: United Nations Children’s Fund. OCLC 670238348.

United Nations Development Programme. 1998. Namibia Human Development Report 1998.

Windhoek: UNDP. OCLC 47075453.

Wolf, Maryanne, and Catherine J. Stoodley. 2008. Proust and the squid: The story and science of the reading brain. New York: Harper Perennial. OCLC 191932021.

Working Group of Indigenous Minorities in Southern Africa. 2005. Working Group of Indigenous Minorities in Southern Africa (WIMSA): report on activities April 2004 to March 2005. Windhoek: WIMSA. OCLC 69992992.

Ibid. 2008. Working Group of Indigenous Minorities in Southern Africa (WIMSA): report on activities April 2007 to March 2008. Windhoek: WIMSA.

[1] There are at least 10 distinct San populations in Namibia, the largest five in order are Hai//om, Ju|’hoansi, !Xun, Kwhe, Naro, and =Au//eisi (Biesele & Hitchcock 2011, 6)

[2] For a more complete history of these events see Biesele & Hitchcock, 2011, 198-227.

[3] Skeef confirmed he wrote this comment via personal communication to the author on September 19, 2014.

[4] National Public Radio (NPR) demonstrated with a recent April Fools’ Day prank that many people comment on articles they have not actually read, and therefore the number of comments on any web article is not necessarily equal to the number of people who actually read a particular article (Hathaway 2014).

About the Author and Photographer

Philip Kreniske is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Human Development Psychology Program at the Graduate Center and a Writing Fellow at Baruch College. He is an editor for theSociety for the Teaching of Psychology Graduate Student Teaching Association (GSTA) blog and he maintains a personal blog on OpenCUNY. Philip’s research focuses on the intersection of technology and education with a particular emphasis on expressive writing in digital contexts. His dissertation explores how diverse college freshmen used interactive writing media as a tool to reflect on their transition to college and what difference this made in terms of their social relational writing and academic achievement.

Jesse Kipp is a travel writer,photographer, and videographer, with a master’s degree in journalism from NYU.