Digital Literary Pedagogy: Teaching Technologies of Reading the Nineteenth-Century

Roger Whitson, Washington State University

Digital Literary Pedagogy: An Experiment in Process-Oriented Publishing

- Introduction & Timeline

- Digital Literary Pedagogy: Teaching Technologies of Reading the Nineteenth Century

- Practicing Collaboration in Process and Product: A Response to ‘Digital Literary Pedagogy’

Digital pedagogy is at a crossroads. Many humanist scholars have begun experimenting with digital technology and reporting those experiments on Twitter, in blogs, and in journals like The Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy. At the same time, our more traditional disciplinary structures limit the amount of critical reflection or pragmatic application those experiments have. Scholars in the field of Computers and Writing, Cheryl Ball for example, have criticized the digital humanities as being “uncritical of its teaching practices,” something she calls “paradoxical,” since DH is “mostly comprised of literary-critical scholars.” Yet these critics are unaware that their “discovery of teaching with technology is relatively new” (Ball 2013). Ball’s Spring 2013 “Logging On” column in Kairos calls most pedagogical sessions at the MLA, THATCamp, and HASTAC “boring,” especially since, unlike scholarly-article length pieces that situate themselves in a field, most digital humanities pieces on pedagogy have a “Here’s What I did in my Classroom” approach (Ball 2013). While I empathize with Ball’s argument that the digital humanities needs more critical reflections on technological pedagogy, I also think that her criticism is symptomatic of an academic institution that has not yet conceptualized the scholarly place for faster-paced conversations like those on blogs and Twitter.[1] Reports of classroom activities certainly have their place in the larger conversation about pedagogy, even if these conversations are not citing articles that have bearing on their understanding of digital practice. This article will show how a scholarly reflection based in actual classroom practice can provide an effective way of bridging Ball’s concerns with the experiences of actual students in my classroom, while doing so from the disciplinary standpoint of literary studies. My fundamental question: what can literary studies contribute to the interdisciplinary pedagogical issues surrounding digital media and online publication?

I decided to collaborate with JITP editors Kimon Keramidas and Amanda Licastro because I wanted to use the academic journal to drive questions of student publication and online participation in a literary studies course. Many DH-pedagogies emphasize the publication of student work. On his course websites, Brian Croxall regularly includes a section to his students titled “Why Blog?” and answers the question by arguing that “f we draw attention from the outside world, it will help us remember that college is not simply preparation for ‘the real world’ but that it is in fact a vital part of the ‘real’ world” (Croxall 2012). I agree with Croxall about the importance that students work have resonances beyond the classroom and the need for student work to make a difference. However much we publish student work online, the vast majority of that work is obscured by everything else that competes with it for reader attention. Most content produced on class websites goes unnoticed unless it is actively promoted by teachers or students, both of whom are often overworked or may not know the complexities of online communication. Posting a blog doesn’t have the same resonance as publishing a book did in the nineteenth century, and for this reason, we needed to explore in our course how editorial oversight might help to make work more noticeable.

I realized that The Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy was a perfect choice for finding editors that were invested in the idea of a professional writing environment, but who also understood that the meaning of “professional” was changing rapidly as social media forces journals to rethink their mission and purpose. The need to have an academic “weight” to the material produced by my students and, at the same time, my desire to embrace new forms of scholarly communication in the student’s projects drove my idea that student publication might require a new role for the editor. In many cases, editors are seen outside of the pedagogical process or part of teaching students to become better peer-reviewers.[2] If students published at all, they either created blogs (that might or might not be visited and commented upon by outside readers) or wrote essays that were never intended to have an outside audience. I wanted my students to have an audience and carefully craft their work to be received, retweeted, and reposted by that audience. What if, I thought, I could bring editors in on the process from the beginning? What if editors could help me co-teach the course?

The introduction of digital content, especially guided by a journal dedicated to digital teaching, can contextualize and revitalize the teaching of literary reading. I call this complementary approach digital literary pedagogy: using digital technology to extend what we do in a literary survey class. While this approach can work in other humanities disciplines, particularly courses that examine textuality from a historical viewpoint, I emphasize how literary studies is particularly suited for a pragmatic approach to editorially-guided instruction combined with historical perspectives on editorial apparatuses. My course interweaves the concerns of composition with literary studies: by using technology and cultural research, I argue, we can historicize the emergence of new practices associated with digital media. I’m focusing specifically on literary studies in this article for two reasons. First, literary studies courses are filled with students who have no idea why books from centuries past have any relation to their lived experience. Second, a social media ecology is emerging in front of us that begs critical reflection, and our students do not yet have the tools to know what they are doing when they sign up for a Facebook account or post a blog. A course reflecting on the kinds of “publics” emerging now is urgently needed, and literary studies can use the anxieties over writing and reading in the past as a touchstone to explore how anxieties over social media can be addressed today.

The design of my fall 2012 course at Washington State University, ENGL 366: “The British Novel to 1900,” focused on providing a set of comparisons between two media revolutions: the expansion of middle-class reading and printing in the nineteenth century and the discourse surrounding digital media today. As William St. Clair recounts in The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period, novel-writing and reading during the nineteenth century were associated with a newly-literate middle class. The phenomenon of middle-class readers transformed the literary marketplace, since poetry and novels had different funding models. Whereas poetry was “supply pushed by authors and patrons,” “[n]ovels were demand-led by book purchasers, by commercial borrowers, and by readers” (St. Clair 2004, 176). The emergence of middle-class reading interfaces with a remarkable number of cultural issues defined by the period: the change in attitudes surrounding the literary merit of novels by different classes, the role of the novel in defining specific forms of subjectivity, and the rise of professional writing and editing. For me, the historical question of writing as a profession is particularly important for defining a literary studies whose historical content can help illuminate technology since, as Paul Fyfe has observed, “the entire production-reception complex of popular literature seemed unprecedented, unpredictable, and immense” in a similar way as digital content overwhelms contemporary users (2009, 2).

I found that it was helpful for students to understand, for example, that authors like Jane Austen and Edmund Burke incorporated anxieties about novel reading with much the same tone as Nicholas Carr uses when he asks “Is Google Making Us Stupid?”[3] Austen’s Northanger Abbey is famous for an ambivalent approach to novels and novel-reading. On the one hand, it was clear to my students that the heroine Catherine Morland’s obsession with Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho keeps her from reading Shakespeare and Milton, and thus memorizing lines that could be used to prove she is cultured and more able to attract rich suitors. My student Tyler Andrews noticed Austen’s criticism “that life can be the same as fiction, with danger around every corner” by emphasizing Catherine’s narration of her quite commonplace life. “Catherine,” Andrews observes, “mention[s] a robbery-free ride to Bath, and […] assume[s] the best in everyone” (Andrews 2012). On the other hand, my students found Austen’s famous rant against the literary critics of her day very compelling. In the section, Austen sees “almost a general wish of decrying the capacity and undervaluing the labor of the novelist, and of slighting the performances which have only genius, wit, and taste to recommend them. ‘I am no novel reader;’ ‘I seldom look into novels;’ ‘Do not imagine that I often read novels;’ ‘it is really very well for a novel,’ such is the common cant” (Austen 1903, 35-6). The students grew to understand how a social-realist approach to writing in the nineteenth century emerged out of Austen’s and other authors’ ambivalence toward novel-reading.[4] The relationship between this ambivalence and the development of the novel is made in the work of Richard Altick and Patrick Brantlinger, who formed the intellectual core of my course.[5]

Reading the Nineteenth Century Aloud

It was useful for me to complicate my students’ notions of reading with those from the critics and authors of the nineteenth century. Many critics have noted the period’s communal reading practices, including the public readings Dickens gave at the end of his life and the common practice of reading aloud to one’s family.[6] Charles Kent attended the readings and wrote about the audience’s breathlessness upon hearing Dickens’s voice “– the words he was about to speak being so thorough well remembered by the majority before their utterance that, often, the rippling of a smile over a thousand faces simultaneously anticipated the laughter which an instant afterwards greeted the words themselves when they were articulated” (Kent 1872, 20). We read Kent’s book Charles Dickens as a Reader along with Edward Cox’s 1878 guide to public reading, The Arts of Writing, Reading, and Speaking in Letters to a Law Student. Cox gives powerful and specific advice about topics as various as overcoming shyness when reading in front of an audience, affecting different voices and practicing different lines before a performance, and reading aloud when preparing for public speaking. He also examines acoustics, advising his readers to practice in the performance room before their event to make sure audiences can hear them. “If they [the audience] fail to do so,” Cox argues, “not only are the distant deprived of whatever pleasure you can give them, but there is sure to be restlessness among those who cannot hear which will disturb those of the audience within earshot and annoy you not a little” (Cox 1878, 183). The nineteenth-century readings by Kent and Cox inspired me to construct a project that asked my students to record oral reading performances of Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey on Soundcloud and write about the experience.[7] Soundcloud is like many online audio distribution applications, except that it makes collaboration between different members extremely easy. The application also assigns each sound a specific URL and has a variety of different widgets that can be used to embed the file into websites. I wanted to have the students thinking about the presence of sound and its resonance both in the nineteenth-century and as an emergent mode of composition within our own digital media space, particularly in the rise of commercial services like Audible and open source community projects like Librivox. Jeff Rice, in “The Making of ka-knowledge: Digital Aurality,” uses both Marshall McLuhan and The Beastie Boys to show how aural modes of composition are central in digital media. These aural modalities, for Rice, depend less on a literate notion of topos for organization and more on aural conventions like rhyme, tonality, rhythm, and voice (Rice 2006).[8] I knew that the knowledge my students would gain from performing the novels in question would be very different from the knowledge gained in an argumentative paper. As such, the book by Brian Cox provided both a historical source and a theoretical guide for our new practice. My students were asked to demonstrate their interpretation of each character in the tonality they used to perform them. Each student picked an individual chapter of the novel, and were encouraged to distinguish the narrator from each of the characters, possibly add music, then edit the recording. They translated the topos often encapsulated in a thesis statement and supporting arguments into the speed in which they read the lines, the surprise or sarcasm in their voice when they performed a character, and the music they used to imply the overall feeling of a scene.

Devin Truchard was particularly good at dramatizing the different voices of the novel, powerfully affecting the naïve enthusiasm of Catherine, the gruff arrogance of John Thorpe, and the anxious loneliness of Mrs. Tilney. The voice he used for the narrator was low, and seemed a little more appropriate for an action movie than an Austen story. It worked well to highlight the darker tones of the novel, as well as Austen’s mocking attitude toward the Gothic. In his written reflection, Truchard writes revealingly about his struggle to differentiate characters with tonality: “Being able to swap to multiple female voices is something I have never tried before.” Truchard continues, “Being able to get at least one feminine voice was trouble enough, but applying a second voice was almost the death of me. I eventually decided to differentiate the two voices by how much strain I put in them” (Truchard 2012). It was quite interesting to see how using an audio project forced my students to write essays about the novel in ways that were unusual to them. Many of the written responses read more like Cox’s how-to manual, rather than the simple response they were accustomed to producing in most literature classes. They needed to know motivation, character, and plot in order to reproduce the characters in a compelling way, but they could not talk about these elements of the novel without mentioning how they impacted the aural elements of the character’s voices in the recording.

Jenna Walter, by contrast, did little to distinguish the voices of the characters, but she added extremely effective music and was clearly quite enthusiastic about the process. She also did a wonderful job syncing the tone of her narrator’s voice with the accompanying music. The connection between her voice and the music is particularly acute when she gets to Catherine’s “desponding tone,” upon noticing that the day might bring rain in Chapter 11 (Walter 2012). The full strings Walter added in the beginning are quickly replaced by a simple piano playing softly, underscoring the delicacy of the “few specks of rain” Catherine sees and the slight depression she feels when she thinks that no one will visit the pump room that day: the center of social activity at the beginning of Northanger Abbey. Walter’s voice betrays a more sincere approach to the novel than Truchard, and perhaps delineates a gender distinction in my class’s reception of its topic. Whereas the men in the course tended to see the conflicts of the novel as inconsequential and somewhat satirical, the women often either empathized with Catherine’s plight or were extremely harsh in their reactions. Walter compares Catherine’s despondence in the novel in which she “may not sleep well […] from all her crying” to “the Twilight series when Edward leaves Bella and she spends half the book in a fetal position, in a majorly depressed state of silence, or a seriously suicidal state.” Given that Walter describes Bella and Catherine as “overreact[ing] to their boy problems,” you can see that she takes the novel much more personally than Truchard seems to with his pseudo-mocking tone (Walter 2012).

The discussions emerging out of this project were often more interesting than the projects themselves. Students connected the physical experience of reproducing voices to gender issues and imagined their own subjectivity in relation to the male and female characters in the novel. Inasmuch as Truchard distinguished different female voices by using different amounts of “strain,” Emeri-Erin Callahan over-emphasized the arrogant masculinity of Mr. Thorpe as a way of articulating his difference from the female characters. Callahan describes “lower[ing] my voice, and [speaking] in a very short and direct manner. I wanted it to feel like he was aggressively asserting himself with every sentence he spoke” (Callahan 2012). She recounts in detail the way she varied the rapidity of her reading to create this effect. “I noticed that he [Thorpe] drove his attention away for a moment onto Mrs. Allen,” Callahan recounts, “asking how she was, and then voiced an additional question about the ball the night before, but before she could even respond he had already turned his focus onto Catherine telling her to hurry up” (Callahan 2012). The darker side of Mr. Thorpe’s dominance is much more pronounced in Callahan’s recording than the mock masculine tone used in Truchard or the sincere yet ultimately judgmental approach by Walter. Callahan “convey[ed] this act [Thorpe’s domination] by making the portion addressed to Mrs. Allen rushed and quiet before I immediately leapt back into talking to Catherine, as though my speech to Mrs. Allen never happened” (Callahan 2012). Callahan made it clear that she understood how speech could be used as a weapon, and she inserts this awareness into the texture of her recording.

The Soundcloud assignment was effective in my course because it highlighted a practice that was common in the nineteenth century, yet used digital technology to bring that practice into the present. Most of the students understood that reading for a computer recorder was quite different than reading for a live audience, but they also learned the importance of going back to old nineteenth century texts for advice. It showed them how critical interpretation could make a tangible difference in how a text is performed. Mark Sample has argued that having students read aloud in class allows them to “become voices in the classroom, authorities in the classroom, empowered to speak both during the reading, and even more critically, after the reading” (Sample 2011). I agree, but I also wanted to show my students how the practice of reading silently emerged only relatively recently. It is important to engage multiple modes of student engagement when dealing with a subject often seen by them as distant and dry. Asking them to incorporate their interpretations directly into a vocal reading practice empowers students to see how criticism can have a practical application in performance.

Editing the Nineteenth Century

I designed the Soundcloud assignment and the blog posts to get students creating as much multimodal content as possible that engaged with the readings of the course. We would then collaborate with Amanda and Kimon to promote the best content, design it as effectively for online users as possible, and create a final site that effectively presented the work of the semester. The readings of the semester shifted from issues of writing and reading to economic and editorial concerns. I found this portion of the course an opportune time to introduce students to the editorial and design practices of bookmakers during the nineteenth century.[9] We investigated Alexis Weedon’s argument about how print runs were initially based upon tokens of 250 that were used to mark the hourly rate owed to the two men who set up the press and ran the copies. “The print run was calculated as the number of such ‘tokens’ rather than by estimating sales,” Wheedon argues, “a practice that was wasteful and clearly untenable in the more competitive 1830s when steam printing challenged the old system” (Wheedon 2003, 12). Of course, such methods were also tied to the economic triumph of the novel as the literary form of the bourgeoisie, as we noted earlier with the work of William St. Clair and Patrick Ballinger. How might we reconsider design choices today if we understood that such choices are shaped by technological and historical affordances? I agree with Kristin Arola when she says that teachers “must (re)engage ourselves and our students with the rhetoric of the interface and thus the rhetoric of design” (Arola 2010, 7). This means, for me, that we should not only have students rhetorically analyze the assumptions of content management sites like WordPress and Drupal, but they also need to know how these assumptions work in a larger historical and cultural frame.[10] My final project would be framed around students editing the content produced during the semester and collaborating with real editors from JITP to make the work publishable. I wrote Sarah Ruth Jacobs of JITP in April 2012 to see if the journal would be interested in rethinking the role of student publication in the class, as well as reconceptualizing the role of the editor in teaching. In my email, I said that:

I’d like to incorporate editors from the journal into the final project. This may mean a session or two where editors Skype in and talk about scholarly editing, what it means, and how to make a “website” publishable. It may mean that we all (myself, editors, and the students) brainstorm during one of those sessions about what it means to publish a website. I’d like to use the project to reimagine the role of the scholarly publication in digital pedagogy – to see editors as part of a collaborative teaching experience. This in itself could be something we could both write about in a separate article, linked perhaps to the website, about having students publish and the role of the peer-reviewed journal in that process. I wanted to see if JITP would be interested in seeing this process as an opportunity for a different type of collaboration and work through what that may mean for my role as a teacher and your role as a publisher. (Whitson 2012)

The response from Sarah, Kimon, and Amanda was positive. Amanda responded that she wanted my perspective as a teacher to be a major part of what was finally produced.

[A]s we are focused on pedagogy, we would like this project to be framed by a narrative in order to reveal the process that led to the final product. We are envisioning a more “meta” submission that would include reflections from both you and your students and perhaps Kimon and me [Amanda]. The reason we are so interested in this proposal is because of its experimental nature, therefore we want to remain true to that goal throughout the creation and in the final deliverable. (Licastro 2012)

We met subsequently on Google Hangout and decided to have the editors virtually attend the class twice. The first meeting would introduce the journal and talk about some larger issues regarding editing and online publication. The final meeting would have students present their blog posts and projects and get pointed critiques by the editors, as well as give the students a chance to reflect on their experiences throughout the semester.

The first hangout meeting went quite well. Students were introduced to the ways Twitter, Facebook, and other social media are changing the methods scholars use to communicate to one another. We discussed how JITP occupied a middle-space between traditional scholarly publications and blogs. They also previewed their thoughts about the final project, where I asked them to curate blog posts produced throughout the semester, picking four of them for the final website. I asked the students to create at least one post per week, based upon a modified version of Mark Sample’s blogging assignment from his Spring 2011 graphic novel class (Sample 2013). That assignment divided students into four groups, and each group had a different stated purpose to their blogging. First Readers would post questions to the week’s reading by Monday night; Responders would respond to questions from the first readers and post their own by Wednesday night; Searchers would find some interesting resource on the web that related to class and discuss its relevance; finally, the Weekly Roundup group would bring the week to a close by reflecting on discussions happening in class and online. We had been producing posts since the first week of class, so by the later weeks we had quite a pool to choose from. Instead of grading them myself, I wanted the students to start practicing their own editorial skills, think about what makes online content successful, and pick out the best examples that fit those criteria from our class.

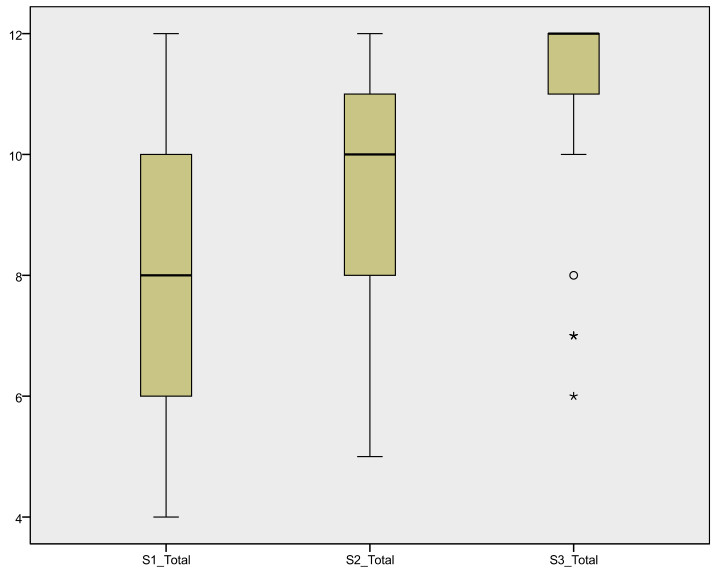

I tasked three students to survey the rest of the class about editorial criteria. The results of their survey found that clarity, content, evidence, and credentials were what most (55%) of the students saw as important criteria. Leech, Champion, and Martin excerpted some of the written responses to the survey in their presentation.

One group noted, “essays must be clear in order for readers to understand, otherwise they will lose interest and have no additional motive to finish reading the piece. If an author does not use evidence to support his/her claims, they lose credibility.” Another group came to a similar conclusion, arguing that “clarity and evidence work to organize the content into a readable form and support the validity of the essay. Credentials further support the author of the essay, which allow the audience to take the author seriously” (“JITP Form” 2012). The students did not choose the same criteria I would, but I feel the exercise gave them the opportunity to see how their thoughts about good work could be put into practice when choosing content to display on the site.

Students then chose the five submissions that best exemplified the determined criteria, and wrote short answers discussing how the submission fit. One student discussing Anne Boothman’s post noted that her piece was “fresh,” that it left “readers thinking and questioning their own feelings about the book’s ending,” and that it cited research to “support her claim” and “her academic opinion.” Another post by Bryant Goetz “demonstrated going beyond the given text and discussing sources that were used in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.” The author of Goetz’s review “thought it was pretty interesting how he linked to Wikipedia right in his article, demonstrating how online writing can reference other sources in different ways than essay writing.” In addition to Goetz and Boothman’s posts, the students picked Colleen Stuckey’s “The Modern Sherlock,” Deven Tokuno’s “Gossip Girl Jane Austen Style,” and Jenna Walter’s “Mary Braddon Drew Inspiration from Her Own Life?” I found that the posts were picked for very different reasons. Deven Tokuno’s analyzed the parallels between Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey and the television program Gossip Girl, which fascinated several of the students who followed the show. Anne Boothman’s was favored because it included a good bit of research into the history of madness in the nineteenth century. Students appreciated the contemporary tone of Tokuno’s, while enjoying the applied research of historical documents in Boothman’s.

Surprisingly, the students seemed more interested in the written blog posts than any of the SoundCloud projects completed during the semester. None of the SoundCloud projects were promoted to the final website. In my mind, despite the large amount of time we spent in class discussing the historical differences between written, aural, visual, and non-verbal modalities, many of the students were uncomfortable articulating specific reasons for picking one non-textual artifact over another. The student reaction may be related to the relative lack of educational infrastructure at WSU devoted to analyzing and producing multimodal content in an academic or professional setting. Individual programs highlight multimodal writing, like the 355 course in our Digital Technology and Culture major titled “Multimodal Authoring: Exploring New Rhetorics,” but there are few resources for scholars or students outside of these courses who want to explore multimodality.[11] WSU has a University-wide “Junior Writing Program” that acts as “a mid-career diagnostic to determine if your writing abilities are ready to handle the challenges of your Writing-In-The-Major (M) courses and other upper division courses that assign writing” (“Junior Writing Portfolio” 2013). The program has been remarkably successful in encouraging writing across different majors, but is only now starting to conceptualize how multimodal and digital forms of writing might fit into its requirements. This has effects on many teachers who might otherwise assign multimodal projects, because such projects would not count in the current portfolio guidelines. The effects of student unease in my course underscores the fact that students in different regions of the country have very different needs when it comes to multimodal literacy, and simply giving them the chance to produce multimodal content in one course may not be enough if other courses and programs on campus continue to be dominated by print assumptions about communication. We spent some time reflecting on how this unexpected consequence put into relief our own historical context, that this same course might look very different five or ten years in the future.

The final part of the project asked students to create their own WordPress website designed to display the best blog posts, summarize the themes of the course, and discuss the major assignments. Students were divided into groups that worked on editing the chosen blog posts, writing an overview of the course, composing a piece on the themes and projects covered in the course, and designing the site itself. Students had to be able to articulate just how historical knowledge can impact current ideas and decisions, and they needed to be able to also present the case for learning about reading controversies in the nineteenth century. For example, the novel Frankenstein clearly associates a literary education with bestowing a certain amount of power on the titular scientist Victor Frankenstein. Students wondered whether literature would play such a central part if Frankenstein were written today. Of course, you only have to look at the reception of the character in film and television for the past hundred years to see that the association between the novel’s veneration of literary tradition and its attitude toward scientific innovation has been largely removed from the story.

The last meeting with the JITP editors allowed my students to connect several of these questions to the larger issues in scholarly communication that concern the journal. Kimon and Amanda asked the design group why they didn’t incorporate more multimodal content. While the site design had a clean interface and visual cues that recalled my own site for the course, it relied largely on the written content that we produced over the semester. The designers did not create video or audio interviews with the authors chosen by the class, nor did they really spend much time considering what kinds of visual images could enhance the content in the posts. The editors also asked the students how collaborative forms of writing were integrated into the process of constructing the site. Much of the site content not devoted to posts or projects was collaboratively written in groups. The students found that the variation between individual and collaborative writing to reflect the writing situations they expected to encounter after graduating from college and getting a job. In all, the suggestions by Kimon and Amanda reflected what might occur in a multimodal composition course: design elements, writing processes, and rhetorical strategies informed much of the early conversation.

The final discussion between the editors and Anne Boothman, however, added a new dimension that was more clearly associated with the literary content of the course. As I mentioned earlier, Boothman had written a piece on the history of madness in the nineteenth century, with special attention paid to Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret. The editors were pleased that her writing led to research in WSU’s library surrounding the questions her reflections had provoked. Was madness always understood in the same way? Amanda’s questions regarding the visual representation of madness were particularly useful for the student and caused her to think more closely about the performance of madness in Braddon’s novel. For me, this conversation showed just how questions of communication and composition can quickly turn into fascinating reflections on culture and subjectivity. If, for example, Lady Audley had acted mad in accordance with the cultural understanding of insanity during Braddon’s lifetime, does this performance allow her to get away with murder? Audley’s performance of madness quickly opens questions regarding gender, the criminal system, even the history of sanity itself.

The Literary in Digital Literary Studies

Boothman’s contribution to the final talk with the JITP editors illustrates just how much digital pedagogy can learn from literary studies. Despite the new methodologies for analyzing texts that the digital humanities have developed, like distant reading and topic modeling, DH itself has little to say about the role of technology in shaping the lives of people throughout history. Students still need to understand how technologies like the novel impacted women, how the rise of women as professional writers challenged what people thought the novel could do, and how novels written by women inspired wider social movements that forever changed the world. And many of the historical issues encountered in a course like the one I designed have analogues in cultural situations students encounter today. For instance, Digital Book World reported on September 6, 2012 that Amazon Publishing Group is looking to market a new set of serialized novels. According to Jason Ashlock, these novels would be “like the serials of publishing generations past, readers can encounter a work of fiction in installments. In classic Dickensian fashion, the long story is fragmented and sold in episodes. A consumer pays one price one time, and each installment is delivered upon its release” (Ashlock 2012). The reference to Dickens is a powerful one, especially if read by students who just finished a twelve-week project reading Oliver Twist from the version of Bentley’s Miscellany found online (Bentley’s Miscellany 1837). Literary studies can show students how history, technology, and marketing collide to bring about a new narrative experience (that may not be so new).

My students also learned quite a bit about the process of writing, editing, and publishing, yet they did so from a perspective that made them aware of the cultural and technological changes which brought about many of the practices used in publishing today. Historicizing reading is important because it shows just how contingent many of our practices can be, while always also illustrating why they were used in the first place. Most importantly to me, however, the emphasis in my course on both the digital and the literary gave my students a sense of historicity that subverted the digital utopianism and apocalypticism so prevalent in our culture today. Students who are used to seeing their teachers lament the rise of Facebook are often shocked to see that something as seemingly innocent as the novel once inspired a similar amount of vitriol. As digital pedagogy can be used to introduce students to new modalities of communication and new skills that are transferrable to different kinds of career opportunities, so can literary studies give students in digital classrooms the ability to critically and historically analyze the culture emerging around them. For all of these reasons, and many others, we need more teachers in literary studies who are willing to experiment with new methodologies, embrace different forms of technology, and write critically reflective articles sharing their teaching with the rest of the discipline.

Bibliography

2011 Course Catalog. 2011. Pullman: Washington State University. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://catalog.wsu.edu/Catalog/PDF_Catalogs/Complete_Catalog_2011-12.pdf

Altick, Richard D.1957.The English Common Reader; a Social History of the Mass Reading Public, 1800-1900. Chicago: University of Chicago. OCLC 1626990.

Andrews, Tyler. “Is Catherine Commonplace, or More Relatable as a Character?” 19th Century Novel: Technologies of Reading. 29 August. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://www.rogerwhitson.net/britnovel2012/2012/08/29/is-catherine-commonplace-or-more-relatable-as-a-character/

Arola, Kristin. 2010. “The Design of Web 2.0: The Rise of the Template, The Fall of Design.” Computers and Composition 27: 4-14. OCLC: 535533696 Ashlock,

Allen. Jason. 2012 “Amazon’s Best News Has Nothing to Do With Devices.” Digital Book World. 6 September. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://www.digitalbookworld.com/2012/amazons-best-news-has-nothing-to-do-with-devices/

Austen, Jane. Northanger Abbey. 1903. Little, Brown, and Company: Boston. OCLC: 2814721.

Ball, Cheryl. 2013. “Editorial Pedagogy Pt. 1: A Professional Philosophy.” Hybrid Pedagogy: A Digital Journal of Learning, Teaching, and Technology. 04 Nov. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://www.hybridpedagogy.com/Journal/files/Editorial_Pedagogy_1.html

Ball, Cheryl. 2013. “Editorial Pedagogy Pt. 2: Developing Authors.” Hybrid Pedagogy: A Digital Journal of Learning, Teaching, and Technology. 27 November. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://www.hybridpedagogy.com/Journal/files/Developing_Authors.html

Ball, Cheryl. 2013. “Editorial Pedagogy Pt. 3: Developing Editors and Designers.” Hybrid Pedagogy: A Digital Journal of Learning, Teaching, and Technology. 11 February. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://www.hybridpedagogy.com/Journal/files/Developing_Editors.html

Ball, Cheryl. 2013. “Logging On.” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy 17.2. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/17.2/index.html

Bentley’s Miscellany. 1837. Archive.org. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://archive.org/details/bentleysmiscell07unkngoog

Boothman, Anne. 2012. “Madness as a Literary Device.” The 19th Century British Novel. 5 December. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://www.rogerwhitson.net/19thcenturyreading/madness-as-a-literary-device/

Brantlinger, Patrick. 1998. The Reading Lesson: The Threat of Mass Literacy in Nineteenth Century British Fiction. Bloomington: Indiana UP. OCLC: 44964643.

Callahan, Emeri-Erin. 2012. “Audacity Reading and Blog.” 19th Century British Novel: Technologies of Reading. 15 September. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://www.rogerwhitson.net/britnovel2012/2012/09/15/audacity-reading-and-blog/

Carr, Nicholas. 2008. “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” The Atlantic. 01 July. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2008/07/is-google-making-us-stupid/306868/

Cook, Susan. 2013. “The Reading Project.” Journal of Victorian Culture Online. 25 June. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://myblogs.informa.com/jvc/2013/06/25/the-reading-project/

Cox, Edward W. 1863. The Arts of Writing, Reading and Speaking in Letters to a Law Student. London: J. Crockford. OCLC: 60718779.

Croxall, Brian. 2012. “Why Blog?” briancroxall.net. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://www.briancroxall.net/dh/why-blog/

Details for DTC 355 Fall 2013, WSU Online. 2013. Pullman: Washington State University. Accessed September 30, 2013. http://schedules.wsu.edu/List/DDP/20133/DTC/355/01

Fister, Barbara. 2012. “Serial Scholarship: Blogging as Traditional Academic Practice.” Inside Higher Ed. 12 July. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/library-babel-fish/serial-scholarship-blogging-traditional-academic-practice

Fitzpatrick, Kathleen. 2013. “Blogs as Serial Scholarship.” Planned Obsolescence. 12 July. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://www.plannedobsolescence.net/blog/blogs-as-serialized-scholarship/

Fitzpatrick, Kathleen. 2013. “The Unpopular.” Planned Obsolescence. 07 July. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://www.plannedobsolescence.net/blog/the-unpopular/

Fitzpatrick. Kathleen. 2013. “Unpopular Seriality.” Planned Obsolescence. 17 June. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://www.plannedobsolescence.net/blog/unpopular-seriality/

Fyfe, Paul. 2011. “Digital Pedagogy Unplugged.” Digital Humanities Quarterly 5.3. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/5/3/000106/000106.html

Fyfe, Paul. 2009. “2008 Van Arsdel Prize Graduate Student Essay: The Random Selection of Victorian New Media.” Victorian Periodicals Review 42.1. OCLC: 428457485.

Goetz, Bryant. 2012. “Are We All a Modern Prometheus?” The 19th Century British Novel. 5 December. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://www.rogerwhitson.net/19thcenturyreading/are-we-all-a-modern-prometheus/

“JITP Form Results.” 2012. Email to Roger Whitson. 30 December.

“Junior Writing Portfolio.” 2013. Washington State University. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://universitycollege.wsu.edu/units/writingprogram/units/writingassessment/juniorwritingportfolio/guidelines/index.html

Kent, Charles. 1872. Charles Dickens as a Reader. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott. OCLC: 4820273.

Lane, Maggie. 1995. Jane Austen and Food. London: Hambledon. OCLC: 32087496.

Licastro, Amanda. 2012. “Re: Question about Possible Publication Idea.” E-mail to Roger Whitson. 14 May.

McCormack, Emily. 2012. “To Read or Not To Read?” 19th Century Novel: Technologies of Reading. 29 August. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://www.rogerwhitson.net/britnovel2012/2012/08/29/to-read-or-not-to-read/

Morrison, Robert and Daniel S. Roberts. 2013. Romanticism and Blackwood’s Magazine. London, Palgrave. OCLC: 811729078.

Rice, Jeff. 2006. “The Making of ka-knowledge: Digital Aurality.” Computers and Composition 23: 266-279. OCLC: 442994478.

Rubery, Matthew. 2009. “Victorian Literature Out Loud: Digital Audio Resources for the Classroom.” Journal of Victorian Culture 14.1: 134-9. OCLC: 378506896.

Sample, Mark. 2013. “Guidelines.” ENGL 300 The Graphic Novel. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://samplereality.com/gmu/engl300/guidelines-2

Sample, Mark. 2011. “On Reading Aloud in the Classroom.” Samplereality. 14 Sept. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://www.samplereality.com/2011/09/14/on-reading-aloud-in-the-classroom/

Sample, Mark. 2012. “Serial Concentration is Deep Concentration.” Samplereality. 12 February. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://www.samplereality.com/2012/02/12/serial-concentration/

St. Clair, William. 2004. The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge UP. OCLC: 53886917.

Stuckey, Colleen. 2012. “Modern Sherlock.” The 19th Century British Novel. 5 December. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://www.rogerwhitson.net/19thcenturyreading/modern-sherlock/

Tokuno, Deven. 2012. “Gossip Girl, Jane Austen Style.” The 19th Century British Novel. 5 December. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://www.rogerwhitson.net/19thcenturyreading/gossip-girl-jane-austen-style/

Truchard, Devin. 2012. “Project 1: Reading Aloud, Chapter 14.” 19th Century British Novel: Technologies of Reading. 15 September. http://www.rogerwhitson.net/britnovel2012/2012/09/15/project-1-reading-aloud-chapter-14/

Walter, Jenna. 2012. “Mary Elizabeth Braddon Drew Inspiration From Her Own Life?” The 19th Century British Novel. 5 December. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://www.rogerwhitson.net/19thcenturyreading/mary-braddon-drew-inspiration-from-her-own-life/

Walter, Jenna. 2012. “Project 1: Chapter 11 – Northanger Abbey Recording.” 19th Century British Novel: Technologies of Reading. 15 September. Accessed September 30, 2013: http://www.rogerwhitson.net/britnovel2012/2012/09/15/project-1-chapter-11-northanger-abbey-recording/

Wheedon, Alexis. 2013. Victorian Publishing: The Economies of Book Production for a Mass Market. Burlington: Ashgate. OCLC: 51022630.

Whitson, Roger. 2012. “Question about Possible Publication Idea.” E-mail to Sarah Ruth Jacobs.

[8] Rice sees the dislocation of topos in aural composition as its contribution to digital pedagogy:

What makes ka-knowledge valuable to any type of writing pedagogy concerned with technology and communication, is how it moves attention away from the dominant topos-themes of knowledge acquisition in terms of power (either empowerment or resistance to power structures) or the still prevalent topos concept of literacy. Ka-knowledge is the digital rhetorical practice of assemblage. Whether it is used for empowering the subject or forging a political or cultural position or acquiring financial stability and professional success is not relevant (though any one of these points may occur). What is important is the recognition of a different method of forming ideas and presenting such ideas. (Rice 2006, 277-8)