Introduction

“The average lifespan of a webpage is 100 days.” This striking statistic has made its way into several popular magazine articles in the last few years. These articles, published in places like The Atlantic (LaFrance 2015) and The New Yorker (Lepore 2015) are alarmist in tone, but they do dispel the notion that the web is a place of permanence. The mourning period for Geocities may be over, but the recent shuttering of Storify, and Photobucket’s “breaking of the Internet” by blocking image links for thousands of users following a subscription restructuring (Notopoulos 2017) remind us that our content will not be available in perpetuity. Even the source of this statistic was hard to track down due to link rot.[1]

It was experiences similar to this one—the troublesome journey through dead links to verify a citation—that inspired the creation of a first-year undergraduate seminar on the topic of born-digital archives, as a way to engage students in the realities of accessing and constructing a historical record. One of the exciting outcomes of the popularity of digital humanities projects in the undergraduate classroom is the increased engagement with the material and staff of local archives and special collections. For college students born in the twenty-first century, these DH projects create a tangible connection with a past where letters, ledgers, and newspapers were the primary modes of mass communication and record keeping. But what about the artifacts of our time? We produce millions of records on a daily basis in the form of email, social media, and the detritus of a 24-hour news cycle. Will these records even survive 100 days? How will future scholars understand the twenty-first century world of fragmented, fragile, and ephemeral knowledge production and storage? What can creators do to ensure their content will survive as a record of their community? How do archivists adjust to a new paradigm where collecting decisions must be made in an instant? Digital archivists are starting to figure out how to handle the vast volumes of data at risk. Just as importantly, they are working to establish best practices for ethical collecting. Is anything on the web fair game for capture? Is it right to ignore robots.txt? For undergraduates, a course on born-digital archives can provide a critical window into understanding modern archival practices, as well as their own responsibilities as media producers and consumers.

This View from the Field will describe a first-year seminar titled “Born Digital,” taught by a university library faculty member within a digital humanities curricular initiative at Washington and Lee University.[2] Since this course was taught at the introductory level in a multi-disciplinary environment, its methods and assignments could be adapted to a variety of classes. The course embedded significant training in digital competencies and information literacy skills within a seminar on digital memory and archival theory. We began with reflective conversations on the experience of being a “digital native,” and then moved on to exploring the concepts and skills necessary to create a born-digital archive using the Archive-It platform.[3] This case study will share the lessons learned while adapting professional archival practices for an undergraduate audience.

Course Design and Framing

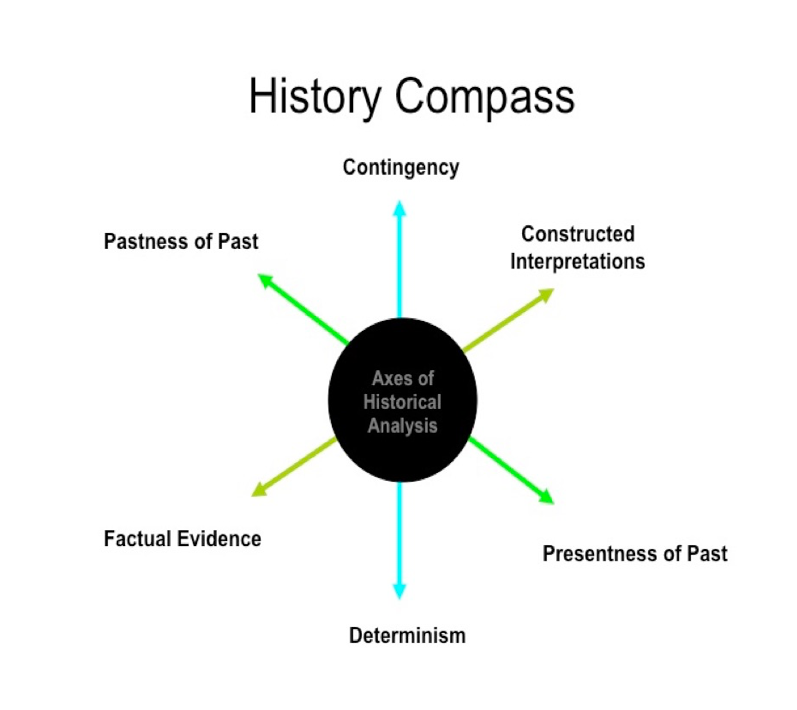

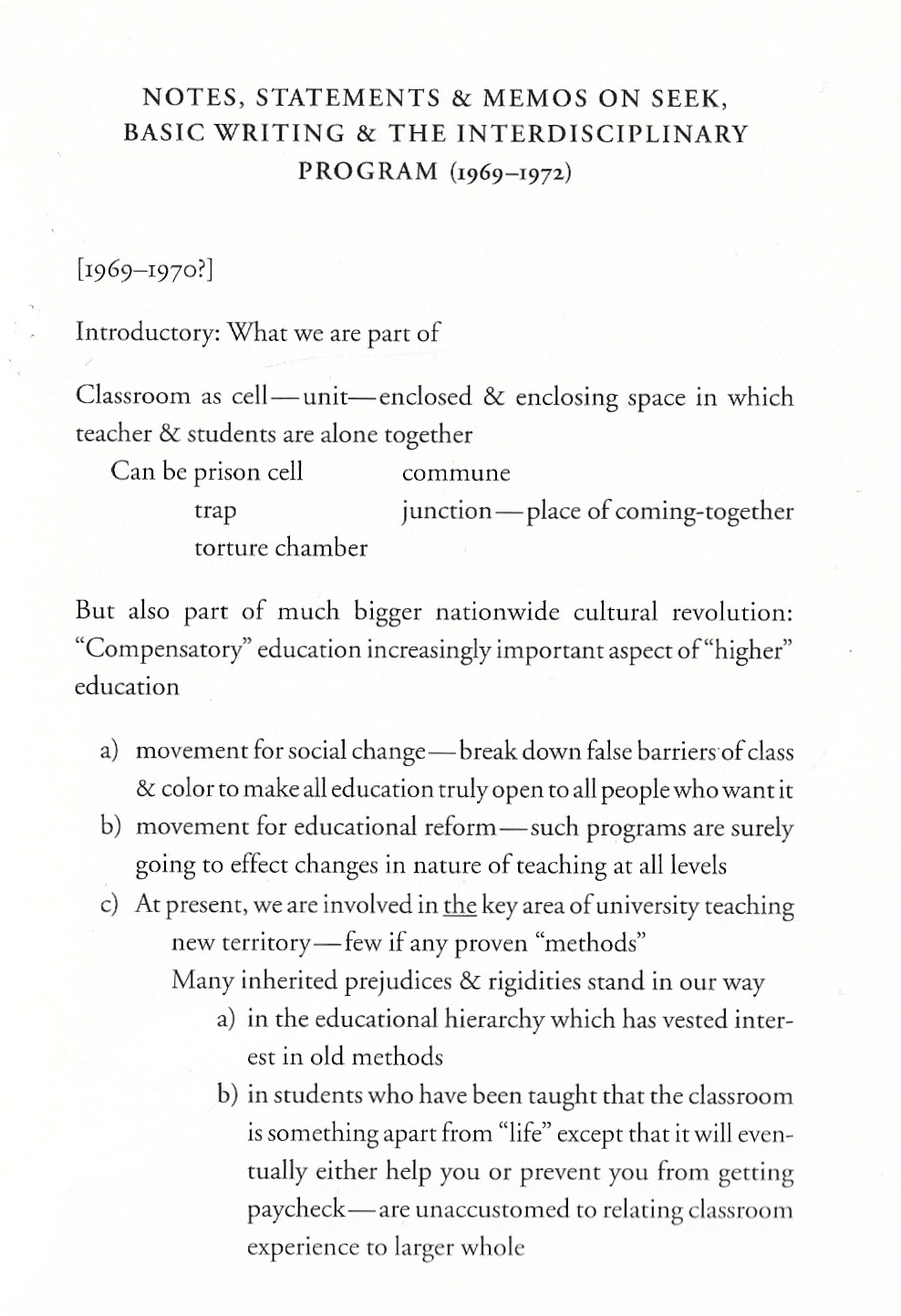

How do born-digital objects and records change the way we approach teaching? There is an abundance of literature on teaching with archival material and digital technologies. A search for model courses returns digital history courses similar to Shawn Graham’s “Crafting Digital History”[4] and graduate-level courses on digital preservation from library and information programs. Creating a seminar on born-digital archives required adapting these graduate-level models to an undergraduate audience unfamiliar with the professional and methodological practices of archivists and historians.

Because our course explored new territory, it was essential to find readings that exposed students to the rich scholarly conversation around archival principles without weighing them down with jargon. Several texts met these criteria and were instrumental in shaping the course. Abbey Smith Rumsey’s When We Are No More (2016) provides a high-level view of our relationship with information. From the ancient Greeks to the development of modern science, Rumsey contextualizes the modern information revolution for students who were born after the invention of Google and reminds us that “we have a lot of information from the past about how people have made these choices before” (Rumsey 2016, 7). For the nuts and bolts of digital preservation, we relied on Trevor Owens’s Theory and Craft of Digital Preservation (2017), available as a pre-print at the time of the course. Not only is Owens well respected in the digital preservation world, his writing is engaging and approachable for undergraduates. Owens’s purpose for the text, offering “a path for getting beyond the hyperbole and the anxiety of ‘the digital’ and establish[ing] a baseline of practice” (Owens 2017, 6) fit well with the goals of the course. Our final course text, The Web as History: Using Web Archives to Understand the Past and Present (Brügger and Schroeder 2017), was essential for modeling the way scholars make meaning from born-digital archives. Ian Milligan’s chapter, “Welcome to the web: The online community of Geocities during the early years of the World Wide Web,” contextualizes Geocities in its time and provides examples of computational approaches to web archives (Brügger and Schroeder 2017).

The learning objectives for the course, listed below, drew from overlapping frameworks.

- Students will learn and be able to apply the principles of archival theory and practice.

- Students will think critically about the use and creation of digital records in their own lives and communities.

- Students will analyze “born digital” archives through the lens of their chosen discipline(s).

- Students will practice methods for collecting and preserving born-digital archives by conducting their own digital preservation project.

These objectives gesture toward the established digital humanities learning outcomes from A Short Guide to the Digital_Humanities[5] (Burdick et al. 2012), adopted by our curricular initiative. These outcomes emphasize the ability to assess information technologies and practice design thinking. The Association of College and Research Libraries’ Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education served as this course’s backbone (Association of College and Research Libraries 2015).[6] Students were asked to think critically about information in every assignment. From writing an annotated bibliography to creating metadata for their web archive, students moved from savvy information consumers to thoughtful information producers. The lab exercises drew from Bryn Mawr’s Digital Competencies initiative and framework. Students developed “digital survival skills” like file structure navigation, troubleshooting, and digital writing and publishing skills like HTML and CSS (Bryn Mawr College n.d.).

Structure and Assignments

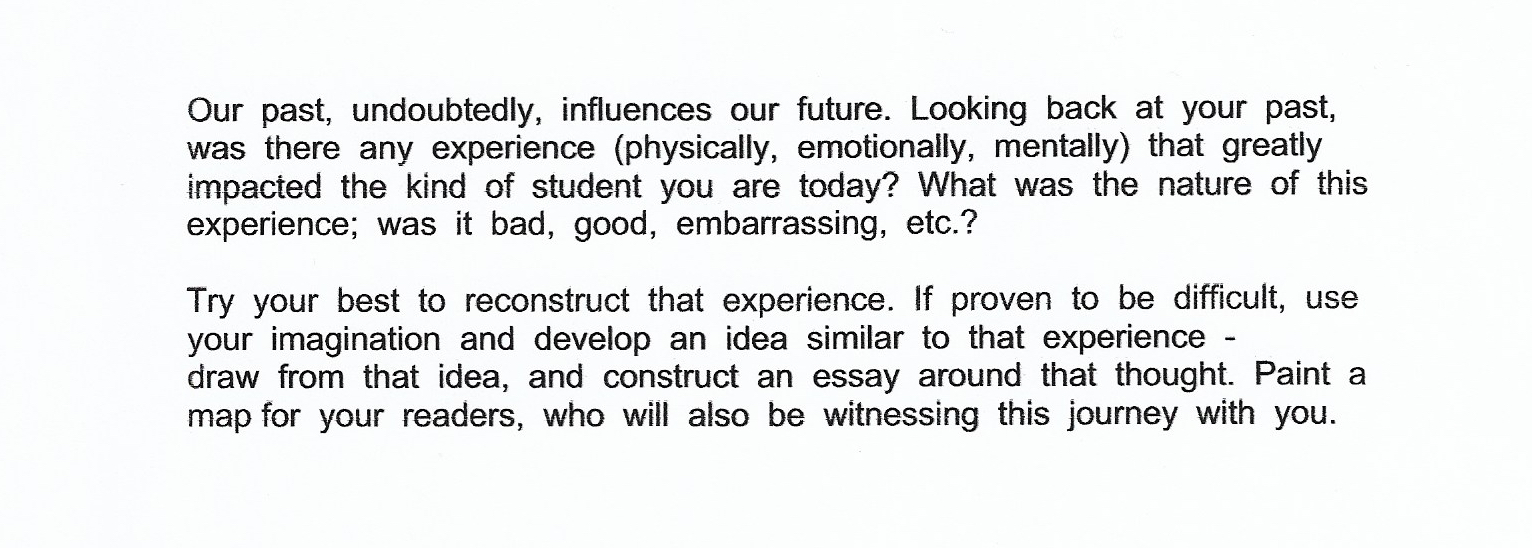

This course[7] took place during a twelve-week term in the winter of 2018. We met for ninety minutes twice a week and divided the week into discussion and lab days. Thematically, the course began with three weeks of introductions to the major concepts of the course: the idea of the “digital native,” collective memory, record keeping, and archives as institutions. The first assignment was a personal essay on these concepts and provided an initial indication of students’ comprehension and writing ability. Starting with this framing gave students an opportunity to share personal information and ultimately created a strong sense of community within the class.

In week four, we transitioned out of the personal sphere with a visit to the university library’s Special Collections and Archives department. After an introduction to the unit and its operations, students formed small groups and selected from a small pool of manuscript collections. For the second assignment, students unpacked each collection to learn about its creator, context, and provenance. The hands-on experience with archival sources readied them to consider individual archival principles like original order and respect des fonds (the idea that archival records should be grouped by creator). We even discussed the role and resources of the Special Collections and Archives department within our institutional context.

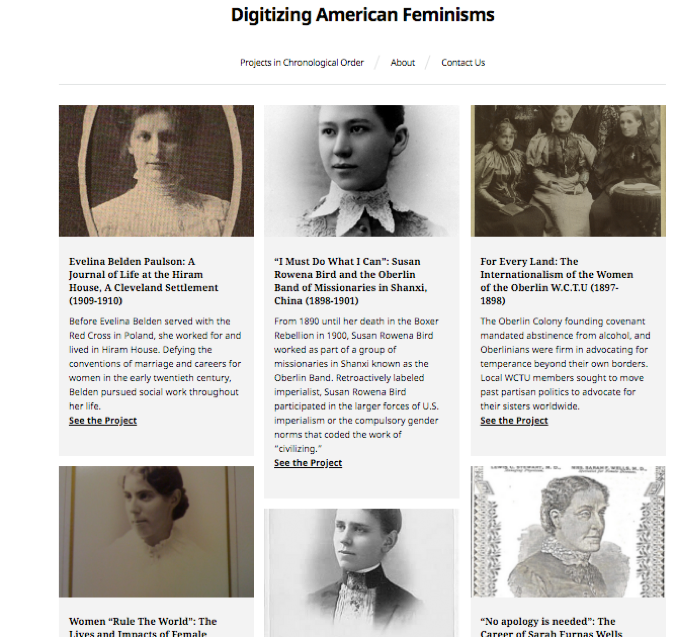

After week seven, we devoted each week to discussing one aspect of the records management lifecycle—appraisal, acquisition, arrangement and description, access, and outreach. Students worked toward their final project through a series of assignments: an annotated bibliography of existing born-digital collections and scholarly articles on a potential topic, a proposal for their born-digital collection, a process log, a short presentation, and a final reflection. Their final project was conducted through an educational partnership with Archive-It, a web archiving service. For a fee, we received 15GB of space in an Archive-It account and a live training session from an Archive-It staff member. Students selected ten websites on a topic of their choosing, from NFL protests to cryptocurrency.[8] They crawled each of their URLs to create a snapshot that would be preserved by the Internet Archive. The process log was the primary graded product to ensure that platform difficulties did not unevenly affect students.

Labs and Technical Skills

Throughout the course, we held a series of lab days to learn the technical skills necessary for the web archiving project. Lab days were relaxed and instructions were available on the course website so students could work at their own pace. Grouping students by operating system helped with peer-to-peer problem solving when technical errors occurred. On the first day, we built simple websites with HTML and CSS—essential languages for troubleshooting captured websites in Archive-It. Another lab session focused on the command line, using existing tutorials like “The Command Line Crash Course (Shaw n.d.).[9] This skill came in useful when a guest speaker led a workshop on Twarc, a command line tool for capturing social media data (specifically Twitter), created by Documenting the Now.[10] One of the most engaging lab days was spent making glitch art to complement our discussion of file fixity in digital objects. We modified images and audio by opening the files in a text editor and scrambling the content to demonstrate the fragility of digital files.

All of the labs contributed to improving computer and web literacies. Despite their reputation as digital natives, most of the first-year students did not know much about how the web worked. Working with HTML or the command line was an exciting look behind the curtain. Not only did the labs improve specific skills, they helped students become comfortable learning and troubleshooting digital tools.

Results

Students successfully achieved the goals of this course. The primary challenge from the instructor’s point of view was translating professional concepts to a first-year audience. The projects and lab activities were essential in bringing archival principles to life. The opportunity to work with manuscript collections was a highlight for many students and let them experience the realities of archival work. By using the Archive-It platform, students created something that would live beyond them and the bounds of the course. Working with their own topic was both exciting and challenging. It created a strong level of investment, but required explicit training in generating an appropriate research agenda.

Overall, most students easily met the first two learning objectives of learning archival principles and thinking critically about their own digital footprint. Student performance was uneven regarding the more analytical objectives, such as analyzing existing born-digital archives and creating their own collection. Project-based assignments were new to these first-year students, as was the emphasis on process over product. Student evaluations were positive, with most citing the value of learning about an underrepresented field and gaining a new perspective. However, from the instructor perspective, the best method of assessment would be to track the information literacy practices of the students throughout their college career. As the digital humanities curriculum initiative transitions into a digital culture and information minor, hopefully this type of assessment will be possible.

Conclusion

A course centered on archival research, whatever form it may take, is an ideal vehicle for teaching a range of scholarly practices and content areas. It is important for current students to be able to assess and understand the digital content they consume and produce every day. A course on born-digital archives opens the possibilities beyond specific manuscript collections or institutional records to anything on the web. Students held a range of opinions on the trustworthiness of the government and private institutions as preservers of the cultural record, but they all recognized the value in taking ownership of your data and preventing gaps and biases in collections. Their reflections consistently mentioned the importance of community-created and -controlled archives. Hopefully this case study inspires other instructors to make use of born-digital archives in their teaching.