Introduction

In the mid-twentieth century, a new approach to research and instruction surrounding the history of the book emerged, which advocated for a hands-on mode of inquiry complementing the traditional work performed in a reading room.[1] The bibliographical press movement, as it came to be known, demonstrated that first-hand experience with the tools and methods of, say, an Elizabethan pressroom allowed researchers to put into practice the book history they theorized. In recent decades, the movement’s continued success has hinged largely upon access to appropriate equipment with which students and researchers can conduct these experiential experiments. The reality today is that many more would like to offer an immersive approach to book history pedagogy than have the proper equipment to do so. However, with the proliferation of affordable 3D technologies and advancements in digital library distribution, there is a new opportunity to democratize and significantly enhance access to this and other forms of instruction. This paper reports on efforts of the 3Dhotbed project (3D-printed History of the Book Education) to build a community-populated repository of open-access, 3D-printable teaching tools for those engaging in bibliographical instruction and research. Following a brief analysis of how the project has evolved from decades of application in book history-related instruction, the paper will outline 3Dhotbed’s work toward establishing a community 3D data repository and fostering a community of practice. Beyond the realm of book history, these findings will be relevant to those developing projects using 3D technologies, or anyone working on a digital project that relies upon workflows distributed among partners at many institutions.

An Overview of the Bibliographical Press Movement

A crucial element in the expansion of bibliography during the last century was the advent of the bibliographical press movement. Defined by one of its key proponents, Philip Gaskell, as “a workshop or laboratory which is carried on chiefly for the purpose of demonstrating and investigating the printing techniques of the past by means of setting type by hand, and of printing from it on a simple press,” these pedagogical experiments have provided an ideal environment for scholars seeking to understand the printed texts they study (Gaskell 1965, 1). The movement appeared in the wake of a call-to-action made in 1913 by R. B. McKerrow, which has served as a refrain for book historians over the last century: “It would, I think, be an excellent thing if all who propose to edit an Elizabethan work from contemporary printed texts could be set to compose a sheet or two in as exact facsimile as possible of some Elizabethan octavo or quarto, and to print it on a press constructed on the Elizabethan model” (McKerrow 1913, 220). As he postulated, with even a rudimentary experiential lesson in historic printing, students “would have constantly and clearly before their minds all the processes through which the matter of the work before them has passed, from its first being written down by the pen of its author to its appearance in the finished volume, and would know when and how mistakes are likely to arise” (McKerrow 1913, 220). It would be some twenty years before McKerrow’s course of study was brought to fruition with the establishment of a bibliographical press by Hugh Smith at University College, London in 1934. By 1964, at least twenty-five such presses had been established across three continents (Gaskell 1965, 7–13).

In practice, the work McKerrow’s successors have embarked upon with these bibliographical presses has served to further both pedagogy and research. The hands-on approach encourages students to internalize the processes, forging an intimate knowledge of them that better informs subsequent analysis of texts. In the past several decades, experiential learning theorists have confirmed Gaskell’s adage that “there is no better way of recognizing and understanding [printers’] mistakes than that of making them oneself” (Gaskell 1965, 3). As Sydney Shep has written:

By applying technical knowledge to the creation of works which challenge the relationship between structure and meaning, form and function, sequentiality and process, text and reader, students achieve not only a profound understanding of nature and behaviour of the materials they are handling, but an awareness of the interrelationship of book production methods and their interpretive consequences. (Shep 2006, 39–40)

The continued proliferation of these bibliographical presses stands as a testament to the efficacy of an experiential approach that focuses on the process to better understand the product of printing. This presswork has formalized a methodology through which book historians have established and tested hypotheses regarding how books were printed in the hand-press period. Indeed, much of the foundational work done during the twentieth century to investigate the history of the book relied upon the reverse engineering of historical methods in bibliographical press environments (Shep 2006, 39). However, such advances have not come without significant logistical obstacles. Notably, the acquisition of proper equipment has been a perennial challenge for those wishing to take up this work.

Writing in the early twentieth century, Philip Gaskell described how he relied on the charity of his colleagues at the Cambridge University Press, who lent him their castoff equipment to start his operations. However, these two nineteenth-century iron hand-presses differed significantly from those used in the Elizabethan period. Gaskell acknowledges, “Ideally we should try to imitate the ways of the hand-press period as closely as we can, and the establishments which have built replicas of old common presses are certainly nearest to that ideal” (Gaskell 1965, 3). Modern iron hand-presses such as those given to him mimicked the operations of an Elizabethan common press well enough to foster an understanding of early printing, so long as one understood the historical concessions being made.

Concerns regarding how to procure the right equipment pervaded the early decades of the bibliographical press movement. In his article advocating for an experiential approach, Gaskell included a census of current bibliographical presses and took pains to list the equipment each held, paying particular attention to the make and model of the press and how it was acquired (Gaskell 1965, 7–13). Notably, only one of these was fashioned before the nineteenth century, with most dating to the late nineteenth or early twentieth centuries. Today, even locating latter-day printing equipment proves to be a struggle. Steven Escar Smith has commented upon the increasing difficulty of doing so as the printing industry continues to evolve, adding that “the scarcity and age of surviving tools and equipment, especially in regard to the hand press period, makes them too precious for student use” (Smith 2006, 35). This being the case, one must resort to custom fabrication in order to facilitate the kind of hands-on experiential learning that Gaskell and his colleagues advocated. In today’s market, where securing even a few cases of type can be prohibitively expensive for many instructors, such a prospect is a nonstarter. In order for the bibliographical press movement to grow and expand in the twenty-first century, an updated approach must be adopted.

New Solutions for Old Problems: 3D Technologies in Book History Instruction

The 3Dhotbed project was devised to alleviate the difficulties that would-be instructors in book history encounter when trying to develop experiential learning curricula. Using a complement of 3D scanning and modelling techniques, this multi-institutional collaboration has created highly accurate, 3D-printable replicas that are freely available for download from an online repository. The project is positioned as a confluence of book history, maker culture, and the digital humanities, and is grounded by core values such as openness, transparency, and collaboration (Spiro 2012). Succinctly put, the project proposes (a) the same methods that made the bibliographical press movement successful in the instruction of early modern western printing can and should be applied more broadly throughout the expanding discipline of book history; and (b) 3D technologies, distributed via a digital library platform, are ideal for providing open access to the tools that can promote this pedagogy on a global scale.

Extending the practice of relying upon custom fabrication to build multi-faceted collections of book history teaching tools, we envision a future for bibliographical instruction that embraces additive manufacturing to create hands-on teaching opportunities. The project aspires to continue the spirit of the bibliographical press movement, which was marked by experimentation as inquiry and a commitment to experiential learning, within burgeoning digital spaces. By leveraging the sustainable, open-access digital library at the University of North Texas (UNT), the project democratizes access to a growing body of 3D-printable teaching tools and the knowledge they engender beyond often isolated and institutionally-bound physical classrooms. Ultimately, 3Dhotbed envisions an international bibliographic community whose members not only benefit from the availability and replicability of these tools, but also contribute their own datasets and teaching aids to the project.

3Dhotbed: From Product to Project

The 3Dhotbed team’s initial goal was developing a typecasting toolkit to teach the punch-matrix system for producing moveable metal type. The team captured 3D scans of working replicas from the collection of the Book History Workshop at Texas A&M University as the basis for the toolkit’s design. The workshop’s own wood-and-metal replicas were painstakingly fabricated by experts in analytical bibliography and early modern material culture, and have been used in hands-on typographical instruction for almost two decades.

Successfully developing the typecasting toolkit was an iterative process that included scanning, processing, and modeling the exemplar wood-and-metal replicas into functional 3D-printable tools.[2] The resulting toolkit served as a proof-of-concept, not only for the creation and use of 3D tools in hands-on book history instruction, but also for the formation of an active community of practice invested in their use and further development (Jacobs, McIntosh, and O’Sullivan 2018). Since being launched in the summer of 2017, the 3Dhotbed collection has been used more than 3,100 times at institutions across the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom.

In developing the first toolkit, the project illustrated the potential pedagogical impact of harnessing maker culture to advance the study of material culture. As Dale Dougherty, founder of Make magazine, framed the term, a “maker” is someone deeply invested in do-it-yourself (DIY) activities, who engages creatively with the physicality of an object and thinks critically about the ideas that have informed it. It is a definition that places a maker as being more akin to a tinkerer than an inventor (Dougherty 2012, 11–14). As a tool designed for classroom use, the first 3Dhotbed toolkit includes several distinct pieces, which the end-user must interpret, physically assemble, and enact in order to fully understand. Inspired by the maker movement, this personal engagement with the design and mechanical operations of tools of the fifteenth century, as mediated through those of the twenty-first century, encourages a student to actively construct their knowledge of the punch-matrix system (Sheridan et al. 2014, 507).

The team members immediately implemented the typecasting toolkit into curricula across their respective institutions. At the University of North Texas, Jacobs partnered with Dr. Dahlia Porter to incorporate hands-on book history instruction into a graduate level course focusing on bibliography and historical research methods. The required readings introduced students to the theoretical processes of type design, typecasting, typesetting, imposition, and hand-press printing, but many struggled to connect those processes to the resulting physical texts they were assigned to analyze prior to their visit. In a post-instruction survey of the visit, Dr. Porter stated, “It is only when students model the processes themselves that they fully understand the relationship between the technical aspects of book making and the book in its final, printed and bound form.” At Texas A&M University, where an experiential book history program was already established, O’Sullivan incorporated the typecasting toolkit in support of more ad-hoc educational outreach, such as informal instruction and community events. Doing so allowed detailed bibliographic instruction to be brought into spaces where it might not otherwise appear, illustrating the immediate benefits of portability and adaptability provided by using 3D models outside a pressroom environment.

From the outset, 3Dhotbed was envisioned as a community resource, and the team has repeatedly solicited feedback and guidance from end-users. For example, the team hosted a Book History Maker Fair in 2016, attracting a varied group of students, faculty, and community members. Attendees widely reported that handling these tools was helpful in crafting their understanding of historical printing practices, and expressed an eagerness to attend similar events in the future. Following the project’s official debut at the RBMS Conference in summer 2017, instructors contacted the team to discuss how they were successfully incorporating the typecasting toolkits in their book history classrooms and offered ideas for additional tools to be developed.[3] Simultaneously, scholars involved in similar work reached out to the team with datasets they had generated, hoping to make them publicly available for teaching and research (see Figure 2). This international group of scholars, students, and special collections librarians offered innovative use cases, additional content, and suggestions regarding areas in which to grow, which encouraged the team to develop the 3Dhotbed project from a stand-alone toolkit into a multi-faceted digital collection.

A key feature of this second phase is the involvement of this community—not only in the reception and use of 3Dhotbed tools, but in their creation and description as well. These continuing endeavors have developed into networked and peer-led learning experiences. In moving to this community-acquisition model, the project draws from a wider selection of available artifacts to digitize and include, as well as a broader array of expertise in the history of the book. Moving toward such a model also created an opportunity for the project to benefit from the perspective of independent designers, book history enthusiasts, and makers who work outside the academy.

The success of this distributed model depends on three things: the utilization of a trusted digital library for the data, the development of logical workflows with clear directives for ingesting and describing community-generated data, and considerations for responsibly stewarding datasets of collections owned by partner institutions. Rather than create an unsustainable, purpose-built repository to host the datasets, 3Dhotbed leverages the existing supported system at UNT Libraries. This digital library encourages community partnerships and has a successful history of facilitating distributed workflows for thorough content description (McIntosh, Mangum, and Phillips 2017). The team built upon this existing structure and developed additional tools to facilitate varying levels of collaboration. This model enables the 3Dhotbed project to explore new partnerships within the international bibliographic community while promising sustainability and open access.

Community-Generated Data in Theory

The twenty-first century has witnessed a boom in the development and use of 3D technologies across both public and private sectors. In 2014, Erica Rosenfeld Halverson and Kimberly M. Sheridan pointed to the makerspace.com directory as listing more than 100 makerspaces worldwide, citing this as an indicator of the maker movement’s expansion (Halverson and Sheridan 2014, 503). As of this writing, only six years later, the same directory now lists nearly ten times that figure.[4] With this massive growth in available resources has also come a great expansion in the types of projects and products incorporating 3D technologies and similar maker tools. In some cases, the focus of activities taking place in a makerspace is upon the making itself, with the end-product being only incidental—the relic of a constructive process and physical expression of more abstract ideas (Ratto 2011; Hertz 2016). In others, however, the process is driven toward a specific goal, an end-product that might possess future research, instruction, or commercial value. Such activities include custom fabrication, prototyping, and 3D digitization. In these instances, where the deliverable could be considered a work of enduring value, particular attention must be given not only to the design and manufacturing of the product, but also to its metadata and sustainable long-term storage (Boyer et al. 2017).

In the humanities, where 3D projects have begun to proliferate, we must develop methodologies to guide work of enduring value to ensure its rigor and validity. As in any digitization project, it is important to understand what information has been lost between the original artifact and the resulting 3D model when incorporating it into research and instruction. The field of book history is well prepared to utilize 3D models, as scholars in the discipline have regularly turned to functional replicas to inform their inquiry where precise historical artifacts were not available (Gaskell 1965, 1–2; Samuelson and Morrow 2015, 90–95).

The 3Dhotbed team strives for full transparency in this regard, communicating where concessions to historical accuracy have been made, and attending in particular to the anticipated learning outcomes of each dataset. For instance, the 3Dhotbed typecasting teaching toolkit cannot be used to cast molten metal type when 3D printed from plastic polymers, but is nevertheless effective in communicating the mechanics of how a punch, matrix, and hand-mould may be used to produce multiple identical pieces of movable type.

These decisions are an integral part of producing a detailed 3D model. Most are inconspicuous, but cumulatively they have a real impact on the finished product. Understanding where and how these decisions are made has been one significant outcome of this project. With the progression toward a collaborative model, there is a communal responsibility to make informed recommendations as to how the scanning or modelling ought to be carried out, ensuring a consistent level of quality across the digital assets ingested into the repository. Likewise, it is essential that those who download, print, and use future replicas are able to evaluate historical concessions for themselves. An analogous concern is encountered by anyone conducting research with a microfilmed or digitized copy of a book or newspaper (Correa 2017, 178). These surrogates provide much of a book’s content (e.g. the printed text), but they cannot convey all of the information contained therein (e.g. bibliographical features such as watermarks or fore-edge paintings)—a fact that has limited their utility to book historians.

By contrast, 3D models can enter a repository as complex objects accompanied by supplemental files and other forms of metadata. Through these we have the ability—and the ethical responsibility—to contextualize the digital surrogate with full catalog descriptions, details regarding the scanning and post-processing, and photographic documentation of the original artifact (Manžuch 2017, 9–10). To facilitate the fabrication and use of 3Dhotbed models, information on how best to 3D print these tools is included within the metadata. For example, woodblock facsimiles require a granularity in printing not afforded through fused deposition modeling, or FDM, printers (the most common 3D printer type among hobbyists and publicly available makerspaces). Rather, these tools are better served by resin printing, a process that is suited to the production of finely detailed models. By identifying the appropriate 3D printing process, these supplemental data help mitigate frustration and wasted resources on the part of the end-user.

Community-Generated Data in Production

Expanding the collection to include data contributed from a broader community of practice is the ideal way to continue the original mission of the 3Dhotbed project. By including objects from a variety of international printing traditions, the collection encourages the study of the book over the course of millennia beyond its history in western Europe. Doing so also affords the opportunity to include a more diverse range of expertise for the contribution of metadata, scholarship, and teaching materials in concert with the data itself. However, in expanding the repository, it was imperative the team institute workflows to ensure this phase of the project adhered to the same principles of transparency and accuracy for both data and metadata. Thus, this phase of the project signals a shift from 3Dhotbed acting solely as content generator to content curator as well.

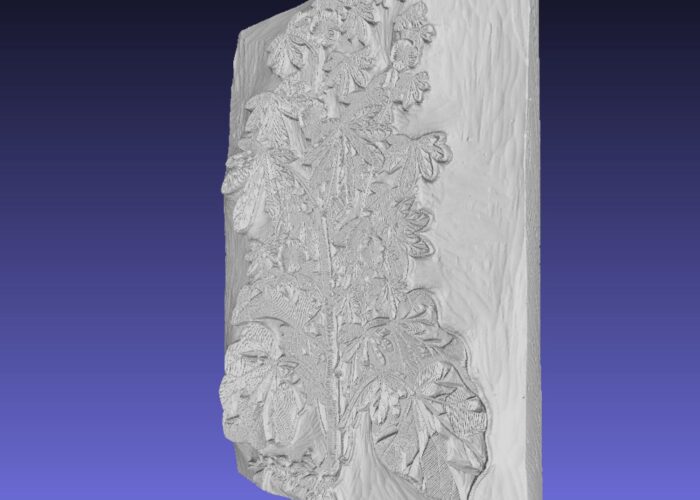

This shift introduced unanticipated hurdles not encountered in previous additions to the 3Dhotbed collection. While some were specific to the objects themselves, other broader issues were the byproduct of putting a community model into production. These included describing uncataloged and/or foreign language materials and managing the institutional relationships that come with hosting others’ data. The first community-generated teaching tool added to the 3Dhotbed project illustrates some of these challenges. Like the typecasting toolkit, it was fashioned in response to a distinct pedagogical demand. While developing the curriculum for a history class covering Qing history through Manchu sources at UCLA, Devin Fitzgerald (an instructor in the English Department) contacted UCLA Library Special Collections staff to arrange a class visit. During their visit, University Archivist Heather Briston introduced the group to a complete set of thirty-six xylographic woodblocks carved during the eighteenth century to print miracle stories, or texts based on the ancient Buddhist Diamond Sutra. Due to their age and fragility, the Diamond Sutra blocks are no longer suitable for inking and printing. In response to the instructor’s desire to facilitate a hands-on learning experience for his students, Coordinator of Scholarly Innovation Technologies Doug Daniels led a project in the UCLA Lux Lab to digitize all thirty-six blocks and create high-quality, resin-printed facsimiles that could be inked and printed to recreate the original text. Working with Fitzgerald and Daniels, the 3Dhotbed team ingested one of these digitized blocks into the UNT Digital Library as a tool for those in the broader community interested in studying and teaching xylography and eastern printing practices (Daniels 2017).

Like many items from complex artifactual collections, the Diamond Sutra woodblock had not yet been cataloged by its home institution, due in part to a foreign language barrier. This limited the 3Dhotbed team’s ability to mine existing metadata to describe the derivative 3D model. However, in collaboration with the instructor, a specialist in both European and East Asian bibliography, the woodblock data was described in both English and Chinese. The addition of the Diamond Sutra woodblock model into the growing corpus of the 3Dhotbed project is an exciting development, as it enhances access to educational tools that help decenter the often anglophonic focus of book history instruction. Developing a system for community-generated description in which scholars are encouraged to describe foreign-language materials is central to developing an international bibliographic community of practice. Additionally, the project’s website supplements the digital collection and creates a space where scholars can host valuable pedagogical materials to help contextualize the teaching tools within multiple fields of study.[5]

Integrating the Diamond Sutra woodblock into the collection also helped refine workflows that will be necessary for taking on larger partnerships in the future. For example, the team realized that community-generated data necessitates community-generated description. Facilitated by the infrastructure already in place in the UNT Digital Library, 3Dhotbed provides two methods for description via distributed workflows, allowing content generators to provide detailed metadata for objects within their area of expertise. These two methods are the direct-access description approach used for larger, more complex projects and a mediated description approach for smaller projects.

The direct access description approach leverages the partnership model already implemented by the UNT Digital Library. UNT Digital Projects staff create metadata editor accounts for individuals and institutions submitting data. The describers then have access, either pre- or post-ingestion, to edit the individual records for items uploaded to the collections under their purview through the UNT Digital Library metadata editor platform. The editing interface was built in-house and includes embedded metadata input guidelines as well as various examples to guide standards-compliant data formatting. The editing platform’s low barrier of entry eases the training required for new metadata creators, and makes it flexible for use by partners with varying backgrounds in description. Additionally, users are able to update descriptions continuously, meaning partners can add additional description based on future cataloging projects or other developing knowledge about an item.

Despite its low barrier of entry, partners still require some base-level training in order to provide standards-compliant description in the metadata editing platform. The 3Dhotbed project required a workaround for ad-hoc partnerships, which led to developing a mediated description approach for smaller scale and discrete datasets. The project team replicates the required fields necessary for standards-compliant description into a Google document along with guidelines and examples that mimic the metadata editing platform. Project partners populate the document with descriptive information for their 3D data, often with guidance from the project team. The project team then formats the metadata as needed for compliance, then ingests the metadata together with the data for the object itself into the digital library.

These foundations offer numerous possibilities for small- and large-scale partnerships with individual content generators as well as institutions. Flexible workflows provide multiple modes of entry for potential partners, scaffolding the iterative steps from acquisition to description, and enable various levels of investment depending on the nature of the project. Additionally, both approaches ensure item description adheres to the metadata standards required for all items ingested into the UNT Digital Library, regardless of format.

With the possibility of varying levels of collaboration comes the added challenge of managing relationships with varied partners. The team anticipated the potential sensitivity of hosting data generated by other makers, which may duplicate digital collections held in other repositories. Fortunately, this is another area in which the 3Dhotbed project benefits from the existing infrastructure in place within the UNT Digital Library and its partner site, the Portal to Texas History. The Portal models itself as a “gateway … to primary source materials” and provides access to collections and data from hundreds of content partners to provide “a vibrant, growing collection of resources” (Portal, n.d.). It mitigates conflict over attribution by establishing clear ownership and credit for each hosted item. The growth of the 3Dhotbed project into a community-generated resource hinges upon carefully navigating these relationships with our core principles of openness, transparency, and collaboration.

The Bibliographical Maker Movement

With the aid of twenty-first century tools and digital library infrastructure, the 3Dhotbed project creates broad and open access to the previously rarified opportunity to work with models of the tools and materials used in historical book production. Moreover, the future success of 3Dhotbed is not solely based on the volume, diversity, or rarity of individual items, but also on the ability of the platform to put these items in conversation. Distributed workflows facilitate the creation of an innovative scholarly portal, which inspired a community around book history instruction in digital spaces while also making possible new facets of original research around these aggregated materials. As this collection of teaching toolkits continues to grow, the analytical practices set forth in the mid-twentieth century are expanded and refined. With the inclusion of a wider array of objects and tools, this bibliographical maker movement reflects the global reach of book history as a discipline. The project strives not only to make examples of these global book traditions more readily available, but also to enable diversity in experiential book history instruction. The Diamond Sutra woodblock now hosted in the digital repository provides users the opportunity to view a full 3D-scan of the original woodblock and download the data necessary to 3D print a facsimile. By virtue of its inclusion in the 3Dhotbed project, the Diamond Sutra is accompanied by a video demonstrating the processes of carving, inking, and printing woodblocks in various time periods, further enhancing the data’s potential as a teaching tool.[6]

In moving toward a community-led project in the second phase, 3Dhotbed has sought mutual investment from the international bibliographic community in developing and expanding a growing corpus of datasets to facilitate their diverse research. In addition to affordably fabricated teaching tools, the 3Dhotbed project will now include high-resolution 3D models of various typographical and technical collections items related to book history, contributed by these new members of our community. As the repository continues to grow, it will digitally collect and preserve 3D models of tools and collections items that are physically distributed across the globe. Thus, the 3Dhotbed project will become a valuable research portal in its own right—a total greater than the sum of its parts that will facilitate research and instruction across institutions and between disciplines to further our understanding of global book history.