Sixty years after her death, social justice activist and 1884 Oberlin College graduate Mary Church Terrell (1863–1954) stood at the center of a team of archivists, faculty, librarians, and students at her alma mater. Inspired by Terrell, we engaged in a series of collaborative projects that demonstrated the potential of digital history to rewrite dominant narratives and inspire activist interventions on our campus and beyond. Born to freed slaves in Memphis, Tennessee, Terrell fashioned an illustrious career as founding president of the National Association of Colored Women, charter member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and relentless leader in campaigns for women’s suffrage and racial equality. Although Terrell herself never encountered “digital humanities,” she became central to our cooperative work on the student-created web-published document projects that comprise Digitizing American Feminisms: Projects from Oberlin College, and she inspired further interventions for social justice on our campus and beyond. This “View from the Field” describes the collaborative digital archival assignment crafted for an Oberlin College history class and its afterlife, including the naming of Oberlin’s Main Library for Mary Church Terrell.

Our project originated in Fall 2012, when archivist Ken Grossi and Professor Carol Lasser attended a workshop on “Teaching the Archives,” sponsored by the Alliance to Advance Liberal Arts Colleges. Together, Ken and Carol designed an assignment for Carol’s history course on American feminisms in which students would transcribe items in the Oberlin College Archives and create “mini-editions”—small documentary projects presenting both digitized images and their transcriptions to make these materials widely available in digital form to public audiences. This assignment built on Carol’s earlier experiences helping students understand the relationship of past and present by creating “How Did Oberlin Women Students Draw on Their College Experience to Participate in Antebellum Social Movements, 1831-1861?” for the website Women and Social Movements in the United States, 1600-2000. In this assignment, Ken saw the opportunity to publicize and make widely available materials from lesser-known and underutilized but significant collections.

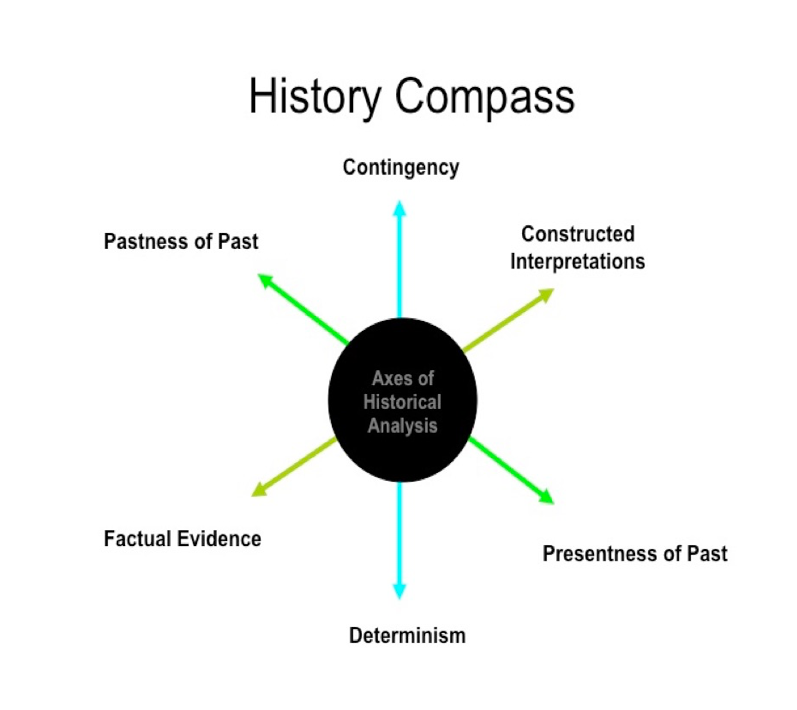

Archival research is the heart of Carol’s history pedagogy. She places the exploration of primary materials at the center of a “history compass,” which she asks students to use to develop their historical thinking. Specifically, the compass has three intersecting axes:

Axis “A” runs between seeming opposite reasons for why we study history: to recover the pastness of the past and to recognize the presentness of the past. Axis “B” connects the contrasting poles of historical causation: contingency, with its emphasis on free will and individual agency, and determinism, with its emphasis on the role played by forces beyond individuals’ control. Finally, axis “C” stretches between divergent methodological positions: the need for research in primary sources to locate evidence and establish historical facts and the need to construct historical interpretations in dialogue with other scholars. (Kornblith and Lasser 2009, 2–3).

Figure 1. Image of a “History Compass” with “Axes of Historical Analysis” at center and six spokes with arrows extending outward: “Contingency,” “Constructed Interpretations,” “Presentness of Past,” “Determinism,” “Factual Evidence,” and “Pastness of Past.”

As an archivist, Ken carefully preselected collections with diverse, accessible, and engaging materials, and flagged points of interest. For example, in the Frances Walker-Slocum Papers, he showed students the program for her pathbreaking 1976 piano recital of African American music at Oberlin. Ken also shared the courtship letter Ruth Alexander wrote to her future first husband describing her efforts to capture a porcupine on film, which enticed students to pursue a project on this multi-dimensional woman of extraordinary drive. Another team took great interest in an 1860 letter from Jamaica written by single missionary Lucy Woodcock to her brother. This focused engagement with specific documents was crucial given the time limits of the busy semester, during which students were also exploring the many interwoven narratives of American feminisms.

The archival assignment was broken into several parts to scaffold the learning goals that develop students’ historical thinking. Each student was assigned to a research team to produce their “mini-edition” based on a particular collection in the Oberlin College Archives. Composed of three students, each team skimmed collections in a special archival session at the beginning of the term and identified their preferred collection. Each individual was responsible for transcribing 500–2,000 words from a particular document or series of documents, which entailed slow, careful reading. In addition, each student produced a heading for their document(s) with identifying information (creator, date, place, type of document), and a 150–300 word introductory note underscoring the importance of context. Every document required appropriate annotations to identify elements that might be new to readers. Each team also cooperatively produced an introduction to their mini-edition, about 500–1,500 words in length, explaining the project’s overall significance and demonstrating their ability to interpret the past. Finally, each group had to produce a bibliography, which highlighted how present interpretations are built on past constructions. Grappling with unfamiliar people, phrases, and ideas, students learned to analyze the distance between past and present.

After Ken conducted an introductory session on archival research methods, students returned regularly to the archives to receive further one-on-one assistance in navigating their collection and related resources. They learned to use finding guides, identify sources and citations for footnotes, and manage digital versions of scanned archival documents. Many students made particular use of the special Monday evening hours at the archives, scheduled to accommodate their hectic days.

Ken and Carol noted appreciatively that students improved their efforts when their assignments could be read by a general audience far beyond their classroom. Yet, while excellent, the completed student projects did not always meet the standards for digital publications on a scholarly website. To improve the quality of these mini-editions, Ken and Carol used local Mellon grants targeted at digital projects plus important supplements from Oberlin College to hire trios of student assistants, primarily recruited from the class, in the summers of 2015 and 2016. As the student assistants improved the quality of these digital mini-editions by incorporating new documents, additional visuals, and even sound recordings, they refined their historical thinking skills and developed editorial expertise. One student focused on the digital layout of our project, eventually guiding us toward the use of WordPress, preferred for its appearance and functionality, especially the ease with which Word documents could be migrated to its platform.

Through their work on Digitizing American Feminisms, the student assistants refined their historical analysis skills. For example, one team of student assistants curated and analyzed the correspondence between antebellum Oberlin African American alumna Lucy Stanton Day and the American Missionary Association. In the correspondence, Day and the association members debated her suitability to serve them at the end of the Civil War. The team of students teased meaning out of cryptic exchanges and came to appreciate the vocabulary of the past on its own terms (Hoak et al. 2015). Another group of students analyzed the courtship letters between early Oberlin students James H Fairchild and Mary Kellogg. The students were horrified by sentences revealing abolitionists’ unreflective participation in racialized culture. Through their analysis of these letters, the students grappled with language and context, eventually coming to terms with the distance between—and proximity of— past and present (Kummer-Landau et al. 2015). The students focusing on Frances Walker Slocum, Oberlin’s first tenured female faculty member of color, pointed out the heartbreaking contradiction that she was shunned by other women teaching in the conservatory, even as the Women’s Movement came into its own (Kummer-Landau et al. 2016).

In February 2015, Oberlin students Sarah Minion, Natalia Shevin, and Michaela Fouad connected past and present through their work on Mary Church Terrell, applying her quest for social justice to current struggles. As Natalia and Sarah later reflected,

Four months before we began our research, in November 2014, prosecutors in Ferguson, Missouri, had chosen not to indict Officer Darren Wilson for the murder of Mike Brown, which reignited national Black Lives Matter protests. On our campus, Black students made myriad demands on the College (Stocker 2014). As we joined protests in Oberlin and Cleveland, we were also making our way through Terrell’s then-modest materials in the Oberlin College Archives. Almost immediately, we saw how experiences of racism like those we now witnessed at school and in national headlines had, in earlier times, motivated Terrell’s life-long pursuit of a more just world, especially for African American women. Discovering, selecting, transcribing, and digitizing Terrell’s papers at the Oberlin College Archives brought her with us into the present at a critical moment. Terrell became for us at once a testament to the ambitious spirit of Oberlin and a guide for who we must strive to be as students, administrators, faculty, staff, and alumni.

When we pored over Terrell’s files, we noticed, stuck between her letters and manuscripts, the business card of Russell Thomas Edwards, a lobbyist in Washington D. C. While Edwards and his relationship to Terrell remain unclear, the phrase he composed in jaunty, deliberate script across the front of his card became our inspiration for understanding Terrell’s tenacity: “You can’t keep her out.” It served both as a warning to all who attempted to silence Terrell in her relentless challenges to institutional barriers that obstructed the advancement of African Americans and women, and as an acknowledgement of her accomplishments in doing exactly that. It spoke to the many ways in which Terrell seized access to the very institutions that tried to keep her—and her commitment to racial and gender justice—out.

In an effort to replicate for our readers our own experiences in the physical archive we used Edwards’ words to title our mini-edition (Fouad et al. 2015). We drew documents from different boxes and different collections to tell our story of Terrell’s confrontation with Oberlin College administrations, as well as with local and federal policy-making agencies. We explored the flexibility of the digital space to construct a coherent narrative from disparate documents, allowing us to highlight Terrell’s simultaneously compassionate and critical relationship to her alma mater. Terrell honored the place that Oberlin College occupied in her own life story and in abolitionist history, but, at the same time, held administrators accountable for its subsequent “back-sliding” on racial justice (Terrell 1914). To allow readers to see this for themselves, we transcribed each document in our project in full. Yet we acknowledge our influence on the narrative through our selection, interpretation, and authoring of introductions to the documents.

We hope her life and words, presented in our digital exhibit, will continue to inform bold progress at Oberlin College and to inspire us as we strive to be active alumni and citizens.

Sarah and Natalia continue to honor Terrell’s legacy—to be unyielding and courageous in the necessary work for social justice.

Their digital work had yet further repercussions on our campus. In a remarkable twist of fate, just after the completion of this class project, Alison Parker, professor of history at the College at Brockport, SUNY, at work on her scholarly biography of Mary Church Terrell, reached out to connect Oberlin students and faculty with Terrell’s heirs Raymond and Jean Langston. In her conversations with the Langstons, Parker emphasized the importance of Terrell’s archives to students, faculty, and staff at Oberlin, and the Langstons chose to donate a number of Terrell’s papers, which remained in their possession. This gift then inspired collaboration between Oberlin’s Africana Studies Program, chaired by Professor Pam Brooks, and the Gender, Sexuality and Feminist Studies Program, which Carol then chaired, resulting in a Spring 2016 conference entitled “Complicated Relationships: Mary Church Terrell’s Legacy for 21st Century Activists.”[1] Joined by the Departments of History and Comparative American Studies, the Library, the Alumni Association, the Oberlin Alumni Association Of African Ancestry, and others, this celebration of the “homecoming” of Terrell’s papers brought together scholars, students, and alumni to explore our histories and our futures. Thinking with Mary Church Terrell, the conference pondered how she could help us understand engagement, respectability, and activism in the digital age. We asked what Terrell’s synthesis of pragmatic and strategic approaches to advancing civil rights and suffrage could teach us about approaching social justice work today.

Mary Church Terrell lingers on the Oberlin campus. In July 2016, newly appointed Director of Libraries Alexia Hudson-Ward could not understand why, as she arranged her books in her spacious office, one volume, Mary Church Terrell’s autobiography, A Colored Woman in a White World, kept tumbling off her shelves. As Oberlin’s first African American and second woman library director, Alexia was deeply impacted by Terrell’s 1896 admonition to pursue “the acquisition of knowledge and…the cultivation of those virtues which make for good” (Terrell 1898, 8). Soon Alexia learned of a movement on campus to honor Terrell’s legacy by renaming the Main Library after her. To her great joy—and with support of the president, key administrators, students, and faculty—the board of trustees voted to approve the Mary Church Terrell Main Library.

In preparation, Oberlin’s librarians rolled out a further digital initiative, Mary Church Terrell: An Original Oberlin Activist. Raymond and Jean Langston gifted additional Terrell papers to the archives during the naming ceremony. Considered together, these collaborative efforts to recover the voices and visions of former Oberlin activists underscore how digital technologies can help shape historical memory.