This Week in Digital Humanities and Pedagogy

June 10, 2015

Anne Donlon

This week: Thinking critically about textual studies, metaphors, and the relationship between DH and STEM Read more… This Week in Digital Humanities and Pedagogy

June 10, 2015

Anne Donlon

This week: Thinking critically about textual studies, metaphors, and the relationship between DH and STEM Read more… This Week in Digital Humanities and Pedagogy

The Cold War era (1940s–1980s) was a time of heavy building within the mainland United States. The construction of the interstate highway system, which in part began as a civil defense scheme, fueled the rapid decentralization of American cities and mass suburbanization. Large defense contracts spawned countless new science, engineering, and manufacturing facilities dedicated to defense-related research. The US federal government also built a considerable number of military bases. From the 1940s to the 1980s, there were nearly 200 military bases constructed in the mainland US (Chambless 1998, 102). Although more commonly remembered as a geopolitical and cultural event, the Cold War was also a significant moment in the history of American architecture and infrastructure. The Cold War unfolded through built space and transformed the US landscape.

A growing fascination among US policymakers with the idea of computer-mediated warfare and the dissolution of the USSR in the early 1990s altered the US government’s perceived needs in terms of keeping and maintaining defense-related property.1 By the last decade of the twentieth century, the US had lost its principal geopolitical rival, and civil defense seemed on the verge of virtualization. As a result, the 1990s saw a rapid reduction in the heavy building of the Cold War era, and much of the defense-related property built during the Cold War came to be re-conceptualized as unnecessary and surplus.2 To this end, the Department of Defense began actively selling off many Cold War–era properties to private land developers, a process that continues in the present day. The developers commonly demolish the properties or adapt them for new and unrelated purposes. Every day, more Cold War sites are torn down, demolished, and then re-built and reused—sometimes leaving little to no record of their existence.

Architects and planners commonly call this type of property re-development “adaptive reuse.” Other common examples of adaptive reuse include the conversion of power plants into art galleries, factories into residential lofts, and abandoned box stores into small clinics or hospitals. The practice of adaptive reuse has gained currency in the building and planning professions for several reasons: cost and time-saving possibilities that can be gleaned (but not always) from adapting an existing site for new purposes instead of building from scratch; a growing interest in sustainable building practices that conserve land and resources by mitigating new construction; and an attraction to the distinctive challenges that many adaptive reuse projects present to builders and planners who understand themselves to be in creative, problem-solving industries (Coffey 2004, 56-7; Shipley, Utz and Parsons 2006, 505-520; Hunter 2007, 10, 13-14). Adaptive reuse has been called an “art form with a cause” (Coffey 2004, 56). The practice often has an environmental, aesthetic, and economic politics to it.

In this essay, I borrow the term “adaptive re-use” and elaborate it into a digital humanities concept. My focus here is the Real Property Utilization and Disposal Website used by the General Services Administration (GSA) to sell off Cold War–era properties to private land developers. The GSA’s property disposal website allows potential buyers to browse through a wide variety of aging defense architecture. Visitors to the website can search for properties by state, property type, or region using simple dropdown menus (see Gallery 1). Visitors can also move through image galleries and obtain detailed property information.

Gallery 1. Screen captures from the GSA’s property disposal website. Accessed August 26, 2012.

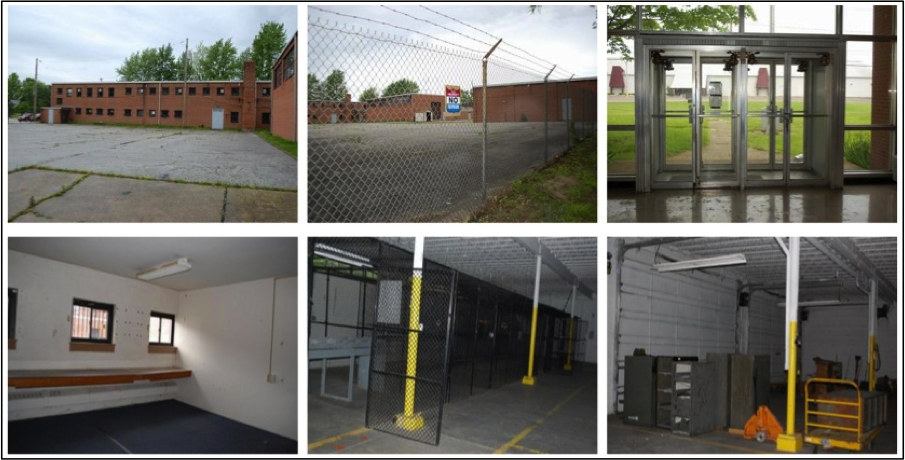

The website auctions everything from office buildings, bases, hospitals, test facilities, laboratories, garages, patrol stations, and warehouses to empty lots, silos, parking lots, and checkpoints. In doing so, the website inadvertently grants intimate access to Cold War–era buildings and built environments that were previously “Off Limits” to civilians, including students and scholars of Cold War history. For example, Figure 1 shows a former army reserve facility in suburban Cleveland that was initially built between 1958 and 1962. Vacated in 2008, the army facility was auctioned off through the GSA’s property disposal website in the spring of 2012. As is typical of the website’s design, prospective buyers were able to access a series of image galleries during the auction process in a manner that simulates a visit to the property in person.

Figure 1. Screen capture from the GSA’s property disposal website. Army reserve facility in Cleveland. Accessed August 26, 2012.

Although seemingly abandoned, the properties listed on the GSA’s property disposal website are often contested places with complicated individual histories. A good example can be found in the case of El Toro Marine Corps Base in Orange County, California. Opened in the 1940s, the federal government targeted the base for closure in the early 1990s. Local officials initially aimed to convert the base to a sizeable commercial airport. After generating considerable anti-airport activism, the project eventually unraveled when a series of ballot measures designated the land for non-aviation use.3 In 2005, a capital investment partnership led by Lennar Corporation acquired the entire El Toro lot through the GSA website with a combined winning bid of $650 million (USD). The initial redevelopment plans for the former military base included 3,500 new homes, 28,000 square meters of retail and office space, a research and development corporate office complex, a set of university branch campuses, a 45-hole private golf course, and a massive public park (Lennar Homes of California, Inc. 2005).4 As part of these re-development efforts, a San Diego recycling company contracted by Lennar and a local NGO dismantled many of the installation’s 1,200 buildings and structures—trucking the doors, floors, windows and wood to nearby Northern Mexico as part of a transnational development project (Rowe 2006).

In 2007, I went to Orange County to conduct fieldwork and to document El Toro’s disassembly (see Gallery 2). Within months of my fieldwork, most of the buildings were unrecognizable, stripped, or gone.

Gallery 2. The disassembly of El Toro Marine Base. Photographs by author.

In the following section of this essay, I shift my attention from documenting processes of physical disassembly to thinking about digital making and re-making. Specifically, I explore how the GSA property disposal website used to sell El Toro and similar properties might be used for teaching purposes despite its intended goal of serving private land developers. My claims are the following: (1) the GSA’s property disposal website provides unique and free Cold War content; (2) it functions like an authentic, albeit buggy, beta version of a digital archive documenting Cold War–era buildings and built environments. Therefore, (3) like the very properties the GSA website features, the website itself is open to “adaptive reuse” into a more properly functioning digital archive geared toward students and scholars of Cold War history.

Thematically, the content within the GSA’s website connects to much of the recent scholarship in Cold War studies, including work on Cold War ruins, work on Cold War geographies, work on elite, off-limits, and technical spaces, work on Cold War domestic environments, and comparative work on “imperial debris.”5 The website makes visible the physical leftovers of abstract geopolitics. Given the content of the website, my discussion here is largely aimed at instructors working in history, anthropology, and allied fields who incorporate digital humanities training into their classrooms. My larger goal, however, is to use this particular case to also expand the idea of “adaptive reuse.” To put forth a working definition: adaptive reuse involves having students assess other people’s digital tools and then work on modifying those tools into scholarly works, resources, or products. The adaptive reuse proposed here can be carried out in three separate steps.

Step 1. The first step of any adaptive reuse project should likely be assessment. The assessment process can be structured as an in-class, group activity or as an individual assignment. Assessment involves asking students to think about the following: What content or services does the digital tool in question currently provide to, or perform for, its users? What features would need to be added, modified, or removed to make the digital tool in question recognizable and functional as an academic entity? In the case of the Real Property Utilization and Disposal Website, the website freely provides original content by inadvertently exhibiting some of the built spaces in which the everyday work of the Cold War happened—capturing the moment just before many of those spaces are sold, redeveloped, and possibly lost from the records. However, the designers of the GSA website organized its search features with property buyers and investors in mind, not students and scholars of Cold War history. In fact, the GSA’s website categorizes each property by its current zoning status and future possible uses (e.g. commercial, industrial, residential), not by its past uses, and certainly not by its potential academic value. Moreover, the Cold War–era properties are mixed together on the website with other surplus government real estate, like old lighthouses and post offices. There are currently no filters that allow users to view only the Cold War–era buildings and built environments. In addition, the GSA website does not currently archive its auctions. Visitors to the website can only view ongoing and upcoming auctions; they cannot access records for properties that were previously sold. These types of observations are what students might draw out during the assessment process. In this particular case, much of the content featured on the GSA’s website has obvious academic value but the design of the website makes that content difficult to use and share for academic purposes.

Step 2. The second step of this adaptive reuse project would be to have students work on adapting the digital tool in question. Depending on the technical proficiency of the students and equipment availability, students might produce mock-ups on paper, write proposals, create wireframes, or actually take up the challenge of adapting the tool for academic use. In the case of the Real Property Utilization and Disposal Website, the work required to turn the website into a functional digital archive geared toward students and scholars of Cold War history might include the following: cataloguing properties based on their past use instead of current zoning status; creating new search features predicated on scholarly terms and interests; building filters for the properties to prevent unrelated government real estate from being intermixed with the Cold War–era buildings and built environments; developing a means to archive the website’s content; developing a means to allow visitors to comment on properties or to create their own image and data galleries; making space for interpretive essays, discussion, or commentary; addressing the stewardship and preservation issues when it comes to digital content; or adding a bibliography that directly connects the website to recent scholarship in Cold War studies—to offer just a few examples.

Step 3. The third step of this particular adaptive reuse project would be to have students present their work and to reflect upon the creative challenges that are specific to adaptation. If the students produced mock-ups or proposals, they can still demonstrate technical proficiencies by addressing how those ideas might be implemented, and by discussing feasibility. If students actually took up the challenge of adapting the tool in question for academic use, the opportunity to present their adaptation(s)—be it one small component or a complete and working tool redesign—affords them the opportunity to explain their initial plans, to outline the work completed, and to generate observations about working in, through, and upon decisions and designs previously made by others. Students might also be asked to consider whether adaptive reuse has a politics to it when performed within the context of the digital humanities. Beyond the skill-building aspects of this type of assignment, might it too be an “art form with a cause” that has aesthetic, environmental, or economic stakes?

Because the purpose of the GSA’s property disposal website is to aid the US federal government in the process of auctioning off surplus properties, it is designed to suit the needs of potential property buyers. It therefore allows visitors to move through image galleries and obtain detailed property information. But the GSA website can also be re-envisioned as an incomplete digital archive, and rediscovered as a potential site for scholarly and pedagogical projects. As such, like the very properties the GSA website features, the website itself is open to adaptive reuse.

Adaptive reuse projects like the one proposed in this essay offer the potential to scaffold digital humanities training by adding new levels of challenge and practice. Given that many digital humanities projects being developed in the present day will age and thus require, over time, episodic retooling, “adaptive reuse” also has the potential to grow as a digital humanities concept from a level of practice, as described and proposed here, to a specialized area of design knowledge, skill, and expertise. Adapting other people’s digital tools can be a key part of the process of learning how to make one’s own. It might also become the very thing that helps sustain the digital humanities over time by mitigating obsolescence, conserving resources, and creating the possibility for new types of tool aesthetics, layerings, and politics.

Barboza, Tony. 2012. “Orange County’s Planned Great Park a Victim of Hard Times.” Los Angeles Times, October 27. Accessed November 1, 2012. latimes.com/news/local/la-me-great-park-20121027,0,6001604.story

Castillo, Greg. 2010. Cold War on the Home Front: The Soft Power of Midcentury Design. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. OCLC 351318481.

Chambless, Timothy M. 1998. “Pro-Defense, Pro-Growth, and Anti-Communism: Cold War Politics in the American West.” In The Cold War American West, edited by Kevin Fernlund. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press. OCLC 39069512.

Coffey, Daniel P. 2004. “Adaptive Re-use.” Contract 46: 56-57. ISSN 1530-6224.

Farish, Matthew. 2010. The Contours of America’s Cold War. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. OCLC 617508692.

Gray, Chris H. 2003. “Posthuman Soldiers in Postmodern War.” Body & Society 9: 215-226. OCLC 438108206.

Hunter, Pam. 2007. “Saving Time and Money with Adaptive Re-use Projects.” Design Cost Data 51: 10, 13-14. http://www.dcd.com/insights/insights_jf_2007.html.

Kaiser, David. 2004. “The Postwar Suburbanization of American Physics.” American Quarterly 56: 851-888. OCLC 608755840.

Komska, Yuliya. 2011. “Ruins of the Cold War.” New German Critique 38: 155-180. OCLC 701896732.

Krasner, Leonard. 2002. Internet for Activists: A Hands-on Guide to Internet Tactics Field-tested in the Fight Against Building El Toro Airport. San Jose, CA: Writers Club Press. OCLC 53891514.

Lennar Homes of California, Inc. 2005. “Lennar and LNR Place Winning $650 Million Bid for All Four Parcels of El Toro Marine Base, California.” News Release, February 17.

Lockwood, David E. and George Siehl. 2004. Military Base Closures: A Historical Review from 1988 to 1995. Washington D.C.: Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress.

Masco, Joseph. 2006. Nuclear Borderlands: The Manhattan Project in Post-Cold War New Mexico. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. OCLC 61151373.

———. 2008. “‘Survival is Your Business’: Engineering Ruins and Affect in Nuclear America.” Cultural Anthropology 23: 361-398. OCLC 438095863.

O’Mara, Margaret Pugh. 2006. “Uncovering the City in the Suburb: Cold War Politics, Scientific Elites, and High-Tech Spaces.” In The New Suburban History, edited by Kevin M. Kruse and Thomas J. Sugrue. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. OCLC 62090790.

Rowe, Jeff. 2006. “Habitat for Humanity Salvaging Building Materials at El Toro.” Orange County Register, August 10. http://www.ocregister.com/news/old-36671-habitat-buildings.html.

Shipley, Robert, Steve Utz, and Michael Parsons. 2006. “Does Adaptive Reuse Pay? A Study of the Business of Building Renovation in Ontario, Canada.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 12: 505-520. OCLC 366072723.

Stoler, Ann Laura. 2008. “Imperial Debris: Reflections on Ruins and Ruinations.” Cultural Anthropology 23: 191-219. OCLC 438095852.

About the Author

Brian Beaton is an Assistant Professor at the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Information Sciences. His research and teaching interests include science and technology studies (STS), archives, social and cultural theory, information workplaces, design, public and applied history, scholarly communication, digital humanities, and public policy.

Notes