Francesco Crocco, Borough of Manhattan Community College

A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. And when Humanity lands there, it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sail. Progress is the realisation of Utopias.

—Oscar Wilde

This essay describes an experiment with critical simulation—the pedagogical application of simulation to foster critical thinking. I theorize this technique in comparison to standard simulation pedagogies and point out some examples of existing simulations and games that achieve similar results. In order to model critical simulation pedagogy for post-secondary education, I describe one instance of this technique that occurred in an elective course on utopian literature I taught at the Borough of Manhattan Community College of The City University of New York, a bustling community college in downtown Manhattan with a majority African-American and Hispanic working-class student population. In the course, I assigned students to work in groups to design a multimedia brochure for an intentional community (i.e., a planned residential community that is a social experiment in utopian living).

During the semester, students worked in groups to draft pieces of the project in response to in-class “challenge” assignments that asked them to devise solutions to social, political, economic, and environmental problems. They then used this material to assemble brochures, which they presented to the class at the end of the semester. Throughout this process, students engaged course texts both as resources for invention and as artifacts for critical evaluation.

My hypothesis was that by turning students into active producers of utopia via a critical simulation they would be in a better position to meet course objectives, namely to learn the conventions of utopian discourse and to adopt a critical utopian frame for evaluating utopian texts and real-world phenomena. I evaluated my hypothesis by interrogating the finished products and analyzing debriefing surveys conducted at the end of the semester. The results suggest critical simulation is a promising technique that complements traditional forms of instruction and has much to offer instructors interested in promoting critical thinking, regardless of discipline. They also raise some interesting questions about the relationship between pedagogy, critical thinking, and social change.

Simulations and Learning

Simulations are simplified models of reality intended to teach specific learning objectives (Hertel and Millis 2002, 17). Advocates for simulation pedagogies tout their potential to motivate students, foster deep learning, achieve learning objectives, enable student-centered learning, and bridge disciplinary gaps (Hertel and Millis 2002, 1-14). As a pedagogical technique, simulations have the advantage of providing what James Gee calls situated meaning—the association of verbal instruction with “images, actions, experiences, or dialogue in a real or imagined world” that enrich learning (Gee 2007, 105). Gee observes that situated meaning provides an ideal environment for learning because

People learn (academic or non-academic) specialist languages and their concomitant ways of thinking best when they can tie the words and structures of those languages to experiences they have had—experiences with which they can build simulations to prepare themselves for action in the domains in which the specialist language is used (e.g. biology or video games). (Gee 2004, 4)

By modeling reality, simulations offer learners the ability to “tie the words and structures” of the new domains they are learning to “experiences they have had,” thereby consolidating and deepening their understanding of the new domain by embodying the new knowledge in lived experience.

Simulations have a long history of pedagogical application. The earliest educational uses of simulations focused on military training. These include the Chinese war game “Weihai” developed around 3000 BCE (which later became the Japanese game “Go”) and the sixth-century CE Indian war game “Chaturanga” (a precursor to Chess) (Gilliom 1974, 265). Modern military simulations emerged in 1798 with the introduction of large-scale battle simulations conducted by the Prussian army (Gilliom 1974, 265-66). In the twentieth-century, the U.S. military became a trendsetter in the field, and its wide-scale adoption of simulation and gaming technologies for training and recruitment facilitated the entry of these techniques into the corporate and educational sectors (Mead 2013).

Simulations began to garner significant support outside of the U.S. military in the 1950s. In 1956, members of the American Management Association traveled to the Naval War College and were so impressed by the Navy’s use of training simulations that they were inspired to produce the first widely used management game for corporate training. Boeing and several other companies responded by launching their own training simulations (Gilliom 1974, 266). By the 1960s, growing research and speculation on the benefits of educational simulations drew the attention of elementary and secondary school educators and administrators, who subsequently began to embrace the technique, first by adopting commercial simulations, later by designing their own (Gilliom 1974, 266-67). Then, by the early 1970s, post-secondary education began to follow suit with the adoption of simulations in business, political science, international relations, sociology, psychology, foreign language, and education programs (Gilliom 1974, 270-71).

Simulations and games also gained traction among writing and literature instructors in post-secondary education. Since at least the early 1970s, post-secondary teachers of English composition and literature have experimented with the use of simulations and games to optimize literacy skills and deepen understanding of course texts (Brewbaker 1972, 105). Lynn Q. Troyka produced the first full-length study of the topic with her doctoral dissertation, “A Study of the Effect of Simulation-Gaming on Expository Prose Competence of College Remedial English Composition Students” (New York University 1973), later published with co-author Jerold Nudelman as Taking Action: Writing, Reading, Speaking, and Listening through Simulation-Games (1975). The volume documents six simulations for the English classroom and provides materials to reproduce them. Troyka and Nudelman’s book has been followed by a significant number of studies that focus on the documentation, theorization, or evaluation of simulation- and game-based approaches to the teaching of writing and literature (Sloan 1978; Kroll 1986; McCann 1996; Saliés 2002, 2007; Nash 2007; Kovalik and Kovalik 2007; Colby and Colby 2008; Alexander 2009; Krause 2010; Colby, Johnson, and Colby 2013). These studies demonstrate the rich history and potential of simulations for the teaching of writing and literature specifically, and signal their value for post-secondary education generally.

Standard Simulation Versus Critical Simulation

In each instance discussed above—the military, corporate America, and (higher) education—simulations have been embraced for their uncanny ability to engage learners and situate meaning in ways that optimize the acquisition of a particular domain, be it military tactics, business practices, or discursive fields. These cases share a standard mode of simulation that I call simulation for social reproduction, in which the goal is to impart a certain specialized body of knowledge, methods, or terminology in order to assimilate the learner to an existing domain and thereby reproduce that domain. By participating in domain-based simulations, the learner comes to adopt what David Shaffer calls the epistemic frame of that domain—“the conventions of participation that individuals internalize when they become acculturated [to a domain]” (Shaffer 2005, n.p.). Simulation for social reproduction achieves its learning objectives when the learner has assimilated to the ways of thinking (i.e., the epistemic frame) intrinsic to the domain that is being modeled.

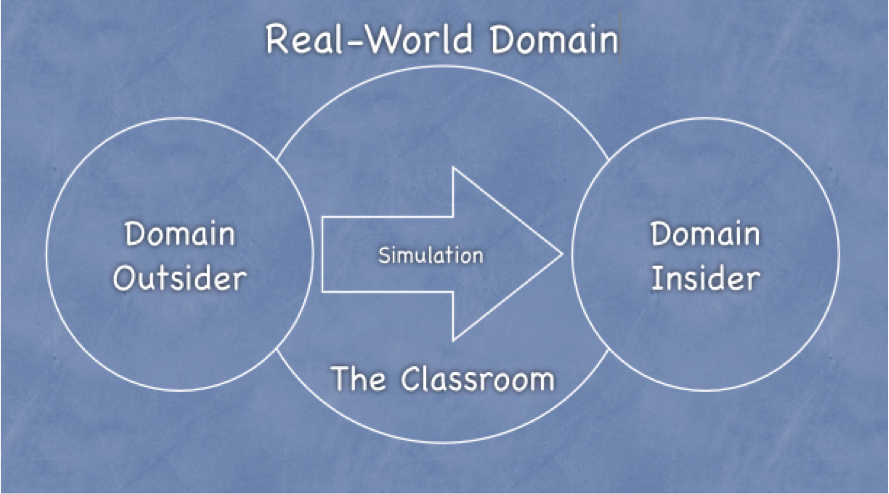

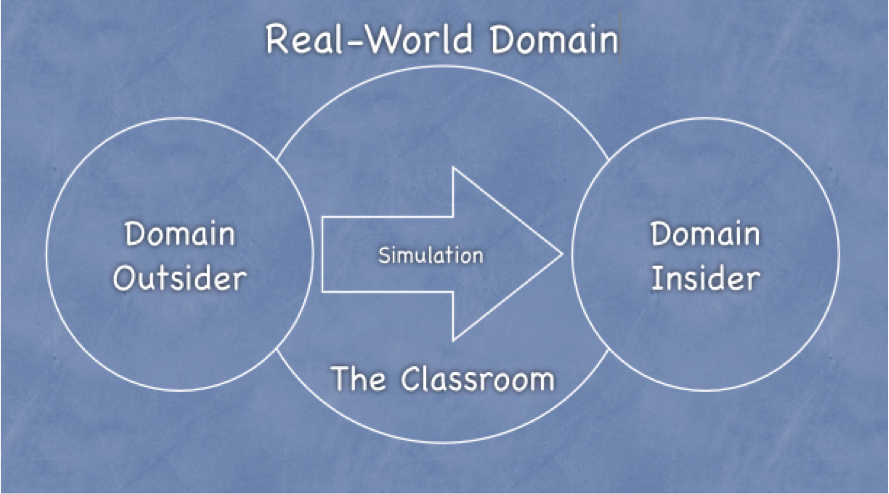

Figure 1. Simulation for Social Reproduction

In the standard simulation for social reproduction, then, simulation is used to bridge the classroom “sandbox” and the real-world domain (see Figure 1). By situating meaning in the classroom, the simulation facilitates transition from domain “outsider” to “insider,” thereby assimilating the learner to an existing domain and the social order to which it belongs.

Simulation for social reproduction can be highly desirable, especially in cases where mastering a domain carries life and death consequences, such as in the use of flight simulators to safely and effectively train the next generation of pilots. Yet, while the engaging and immersive meaning-making environments at the heart of standard simulations may excel at drawing in and assimilating learners to a new domain, by the same token they make it difficult for learners to think critically about those domains, a process that requires distance and defamiliarization. Ira Shor defines critical thinking as:

habits of thought, reading, writing, and speaking which go beneath surface meaning, first impressions, dominant myths, official pronouncements, traditional clichés, received wisdom, and mere opinions, to understand the deep meaning, root causes, social context, ideology, and personal consequences of any action, event, object, process, organization, experience, text, subject matter, policy, mass media, or discourse. (Shor 1992, 129)

Because critical thinking seeks not only to understand but to evaluate domains, a new method of simulation must be devised that poses the subject matter of the new domain not as a body of knowledge to be assimilated and mastered, but as a problem to be analyzed and solved. In this way, the learner can adopt “habits of thought” that make it possible for one to “understand the deep meaning” of the new domain and make critical evaluations.

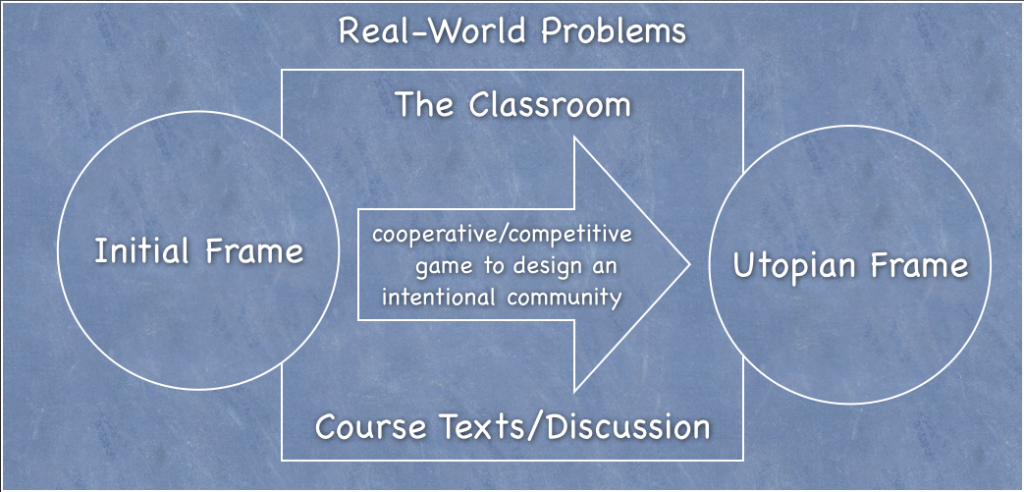

This new kind of simulation, what I call critical simulation, is one approach to practicing critical gaming pedagogy, a model I theorized elsewhere as a technique for using simulation and gaming “to promote critical thinking about hegemonic ideas or institutions rather than to propagate them” (Crocco 2011, 29). Essentially, conventional uses of simulation and gaming for education, which are often promoted as alternatives to the traditional factory model of education, in fact, upgrade this model for a twenty-first century high-tech economy—effectively delivering the factory model 2.0 (Crocco 2011, 29). This complicity with the traditional aims of schooling is evident in the distinction between standard and critical simulation. Whereas the goal of standard simulation is to use simplified models of reality to assimilate the learner as efficiently and effectively as possible into the domain being simulated, critical simulation resists the ideological closure of assimilation by presenting models of reality that defamiliarize the domain in question and pose it as a problem to be investigated and resolved. If successful, the critical simulation will produce cognitive dissonance between one’s pre-conceived notions about a domain and the new experiences generated by the simulation; this opens up a space for critical reflection and analysis. Consequently, instead of moving the learner from a domain outsider to an insider, the critical simulation moves the learner from an uncritical point-of-view to a critical point-of-view about that domain (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. A critical simulation.

While this theorization of critical simulation is new, there are many instances of simulations and games in secondary and post-secondary education that operate like critical simulations. The list of applicable simulations and games includes those designed to challenge economic policies by raising awareness about the effects of social inequality (Schulzke 2013; Norris 2013; Ansoms and Greenen 2012; Fisher 2012; Crocco 2011; Dundes and Harlow 2005; Thatcher and Robinson 1990), address the lack of civic engagement (Bernstein and Meizlish 2003; Raphael et al. 2010) and empathy (Bachen, Hernández-Ramos, and Raphael 2012; Barak et al. 1987), explore the problem of climate change (Sterman et al. 2014; Lee et al. 2013), question urban planning models in light of sustainability concerns (Gaber 2007; Torres and Macedo 2000), re-enact and problematize history (McCall 2011; see also the Barnard College Reacting to the Past series), and teach critical methods for approaching the social sciences (Simpson and Elias 2011; Martin 1979). In seeking to design so-called “games for change,” activists, NGOs, and state agencies have also developed critical simulations. These games and simulations situate the player in contexts where adversity or moral quandaries lead to a re-examination of held beliefs or prevailing logics, thereby moving the player toward a new, more critical understanding of the subject matter. For instance, in the video game 3rd World Farmer, players simulate the experience of a farmer in a developing nation in order to unsettle preconceptions about the etiology of third-world poverty and make explicit its relation to centers of power in the first world. The McDonald’s Video Game puts players at the helm of this transnational corporation and requires them to resolve moral quandaries in which they must weigh profit margins against workers rights, consumer health, and environmental protection. By factoring in these externalized costs of doing business, players can challenge the conventional business ethics and decisions that typical management simulations tend to normalize. These examples demonstrate how critical simulations situate learning within models of reality in ways that problematize rather than preserve established domains or hegemonic beliefs.

Why Use Critical Simulation for Teaching Utopia?

I decided to employ the methods of critical simulation in my course on utopian literature for several reasons. For one thing, both share an emphasis on critical thinking. In Lectures on Ideology and Utopia (1986), the philosopher Paul Ricoeur observes that utopias are vital for the critique of ideology:

This is my conviction: the only way to get out of the circularity in which ideologies engulf us is to assume a utopia, declare it, and judge an ideology on this basis. Because the absolute onlooker is impossible, then it is someone within the process itself who takes the responsibility for judgment. (Ricoeur 1986, 172-73)

If utopia can be described as a “space of hope” that inspires “social dreaming” (Sargent 2010, 5) and nourishes “the desire for a better way of being” (Levitas 1990, 198), Ricoeur adds that it is also, and as importantly, a “space of criticism” that provides a critical vantage on ideology. This parallelism between critical thinking and utopia raises two important conclusions about teaching utopia with simulation. For one thing, since utopia is fundamentally concerned with teaching critical habits of mind—both about other domains and its own—it cannot be paired with standard simulations, which mainly achieve the goal of training and assimilation rather than critical reflection and analysis. Secondly, because the utopian frame—the knowledge, methods, and terminology that comprise utopian discourse—is consonant with critical habits of mind, the experience of deploying critical simulation in a utopian classroom will, paradoxically, have the added effect of achieving the rather orthodox goal of the standard simulation, i.e., specialized training in an epistemic frame, in this case the utopian frame.

In addition to posing critiques of what is, critical simulations and utopias also share in common the desire to imagine alternative configurations for what could be. Ernst Bloch captures this dialectic between critique and creativity by describing utopian thought as “anticipatory consciousness,” the “Not-Yet-Conscious” that “wants to look far into the distance … in order to penetrate the darkness so near” (Bloch 1986, 1:11-12). Scholars have attempted to articulate a “utopian pedagogy” to promote this critical/creative consciousness, noting that whereas the purpose of education is typically “to produce social subjects for the perpetuation of the neoliberal order,” the goal of utopian pedagogy should be “to foster experiments in thinking and action that lead us away from that order” and “point us towards…‘the coming communities’” (Coté, Day, and De Peuter 2007, 14-15, italics in the original). Different strategies have been proposed to achieve the goals of utopian pedagogy. In the tradition of critical pedagogy, for instance, a high value is placed on the relations of power in the classroom. By replacing the one-way “banking model” of education (in which information is “deposited” into students’ heads and “withdrawn” for tests) with a democratic classroom in which power is decentered, authority is shared, and decisions about curriculum are negotiated (Freire 2002; Shor 1996), critical pedagogy models utopia in the present. On the other hand, even if such a democratic space could be constructed within an otherwise hierarchical educational institution the result may be what Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis call a miniutopia—an ephemeral classroom utopia that leaves students “lacking a political understanding of their predicament” (Bowles and Gintis 1976, 255). Consequently, Nichole Stanford suggests that, by neglecting to teach students how to apply the democratic processes of the classroom to real-life circumstances, miniutopian pedagogies “can wind up reifying existing social conditions in the same way that traditional pedagogy does,” either by promoting escapism or leaving students to blame themselves for their inability to assimilate successfully (Stanford 2012, 7-8). What is missing from most utopian models, including critical pedagogy, is the simulation of change or transition from the old social structure to the new. Alternatively, Stanford proposes using the classroom as a “safe house” in which students get to practice how to critique, negotiate, and change society by problem-posing real-world conflicts, beginning with organizing to negotiate changes with the representative authority, the teacher (Stanford 2012, 10). Critical simulation combines elements from both of these approaches: it imagines utopia in the present by decentering the classroom with interactive experiences in which students learn by making decisions and evaluating outcomes, and these experiences involve practicing how to negotiate real-world problems and devise alternatives to the status quo. The difference between problem-posing in social reproduction simulation and critical simulation lies in what is allowed to be a problem: like the safe house model that invites students to change their real circumstances, critical simulation poses current power structures as the problem.

Finally, critical simulations and utopia resemble each other because utopia is itself a kind of critical simulation. In “How to Play Utopia,” Michael Holquist compares chess to utopia, suggesting that “the comparison of chess to battle is roughly parallel to the relationship which obtains between utopia and society” (Holquist 1968, 107). Both, he argues, are simulations that present simplified models of reality—the battlefield and the polis—in which players have the opportunity to replay history and speculate different outcomes. Where the chess player may re-enact historical battles using specialized chess sets carved to resemble particular armies and eras, the player of utopia replays social evolution to produce different kinds of civilizations. In this process, “The irreversibility of history is stemmed, and outcomes determined by the contingency of actual experience, can, in utopia, be reversed in the freedom of the utopist’s imagination… Utopia is play with ideas” (Holquist 1968, 119). Viewed in this manner as a kind of grand simulation, an elaborate “what if” in which authors “play with ideas” in order to imagine different social outcomes, utopias operate like critical simulations: both involve critical thinking, decision-making, and speculation about possible futures.

Designing a Critical Simulation for Teaching Utopia

If utopia is itself an exercise in critical simulation, one in which authors design alternative futures that critique and inspire, what better way for students to learn about utopia than by imitating this process? Students in my course would become designers of utopia, and in doing so they would practice the critical habits of mind intrinsic to the utopian frame and situate their understanding of utopian texts within an embodied experience of utopian design. While a design-based approach to teaching language and literature is not new—it was famously promulgated by the New London Group (of which James Gee was a member) as a pedagogy for multiliteracy (Cazden et al. 1996), this application in a utopian literature course provides a case study for how such a method might work to situate meaning using the techniques of critical simulation.

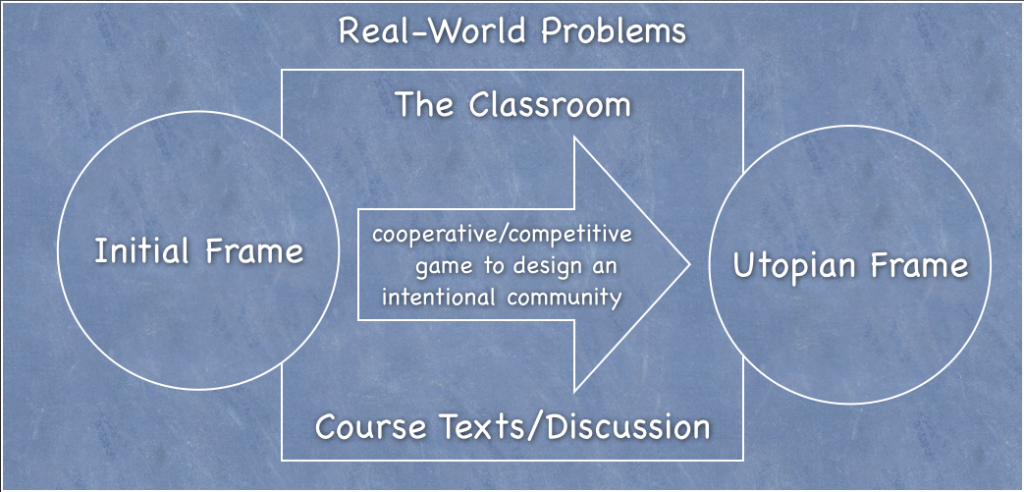

Figure 3. A critical simulation for a utopian literature course.

The critical simulation I designed took the form of a semester-long cooperative / competitive game in which five teams of students designed intentional communities—actually existing social experiments in utopian living. Students developed the designs for their communities through a semester-long iterative process that involved engaging with course texts to prepare solutions to a list of contemporary social problems. They assembled this work into a multimedia digital brochure for an intentional community that each team presented to the class at the end of the semester, which provided a gratifying sense of closure to the course. The classroom thus became a sandbox for utopia: students simulated the experience of designing utopia, and this experience helped them move from using an uncritical initial frame to a critical utopian frame while simultaneously moving them away from being outsiders to becoming insiders in the discourse by providing opportunities to engage course texts and concepts (see Figure 3).

This semester-long process of utopian design was stoked by periodic “challenges”—in-class assignments that followed discussions of course texts in which the class collectively problem-posed some aspect of society criticized in that week’s reading material, and then worked in teams to develop innovative solutions. The challenge themes isolated different components of the conceptual work required to produce an intentional community: (1) the distribution of work and resources; (2) gender roles; (3) education and healthcare; (4) spirituality and well being; (5) government, freedom, and international relations; (6) consumption and waste management; (7) energy and environment; and (8) urban and suburban planning. In the spirit of Ernst Bloch’s conception of the “not yet,” each challenge began with a critique of what is and followed with a discussion of what could or should be. The course texts provided useful resources for this process by modeling utopian critiques and alternatives, but also by furnishing raw material for the students’ designs. The texts included selections from Plato’s Republic, Thomas More’s Utopia, Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward, Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland, George Orwell’s 1984, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, Harlan Ellison’s “‘Repent Harlequin,’ Said the Ticktockman,” Ernest Callenbach’s Ecotopia, and Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower. I also assigned students to read about intentional communities past and present. They read about Charles Fourier’s phalanxes, Robert Owen’s cooperatives, Icarian communes, Brook Farm, the Oneida Community, Shaker villages, and contemporary intentional communities. To round out the course material, students examined urban and suburban planning blueprints, such as Ebenezer Howard’s “Garden City of Tomorrow,” and viewed clips from several documentary films that addressed social and environmental concerns.

While the design process constituted a single, semester-long critical simulation, each individual challenge was the equivalent of a mini-critical simulation that targeted a specific issue in order to provoke awareness and inspire creative alternatives. Through this process, the domains under consideration—e.g., economics, ecology, urban and suburban planning, etc.—were reframed as problems to be solved rather than as normative discourses to be learned and internalized. While the course texts initially served as touchstones for utopian critique and storehouses of fresh ideas, as students became empowered utopian producers in their own right they began to question the texts and treat them as much as codifications of ideology as the domains they scrutinized. At the conclusion of each challenge round, the teams would present their work, provide constructive feedback for revision, and select the most innovative design, after which I would award nominal prizes. They recorded their work on a group blog, which simultaneously functioned as a drafting site for the final digital brochure, a forum for instructor feedback, and a communication hub for the team. This multi-stage, design-based critical simulation enhanced rather than displaced the more traditional pedagogical methods used in the course, such as reading, writing, and discussion. It also integrated the major learning outcomes for the course—reading comprehension, critical analysis, and intellectual production—into a single, unified process.

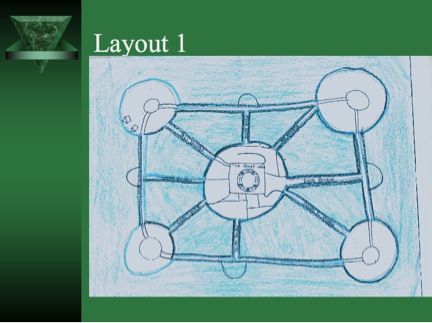

The digital brochures assembled from the raw material of the challenge assignments were required to have four parts: (a) a common mission statement outlining the history, goals and purpose of the community; (b) a description of a typical day in the life of the community; (c) a visual blueprint for a town, village, or city in the community; and, since it was a brochure after all, (d) information about how to join the community. The final products took the form of colorful slideshows, PDFs, and websites. The components for these brochures were copied in part from the Fellowship for Intentional Community website, a promotional catalog of ongoing experiments in “practical” utopias that students were asked to peruse at one point in the semester. Since the website included mission statements, photographs, and contact information for each listing, we used it as a model for the students’ digital brochures.

While the intentional communities website provided a handy model for the students’ projects, it was not my only or even primary motivation for having students design their final projects as digital brochures. This decision hinged on other factors, as well. I chose mass media and marketing genres for this assignment because the goal of “selling” utopia to an audience and recruiting utopians resonates with the persuasive thrust of utopian literature. From Plato’s Republic to More’s Utopia to Callenbach’s Ecotopia and beyond, one finds a common pattern in which the author, through the intermediation of critical or skeptical narrators and interlocutors, attempts to persuade the reader that a better world is possible. This does not necessarily imply that the author has (or even wants) a blueprint for utopia, but it does make persuasion an explicit part of the bargain. Thus, in the same way that a brochure is rhetorically intentioned to sell a product, utopian literature is often rhetorically intentioned to sell an idea—about how one should live or not live. Of course, adopting the format of the brochure—a product so keyed to capitalist commodification and consumerism—for utopian discourse—which is decidedly anti-capitalist—may seem paradoxical. But a crucial part of critical simulation is challenging students to imagine ways to transition from one social system to another; in this scenario, they appropriate existing capitalist tools to launch anti-capitalist structures. Finally, I decided to use a digital format for the brochures because it offered the most versatile tools for taking the different media the students had drafted in the challenge assignments and assembling them into a single document. This material included text, images from the web, sound bites, video clips, photographs, and even hand drawings (one challenge required students to draw a resource map for their community). The final product was a virtual bricolage of a semester’s worth of crafting in the service of utopian social dreaming.

Welcome to Utopias!

The students presented five brochures for intentional communities at the end of the semester: Halo, a tourism and export-based island resort; Vacileeco Palati, a high-tech new-Atlantean commune; Northern Green, a secessionist eco-commune; Guavaland, an agrarian autarky with sprinkles of futuristic technology; and Phoenix, a back-to-nature libertarian community of individual producers. These unique designs display a wealth of critical engagement with contemporary issues and course texts, as well as a keen sense of adaptation and invention. While there is some interesting overlap between the designs, there are also many key differences. In the paragraphs that follow, I provide an overview of each intentional community using snippets of text and images from the brochures. I also highlight where and how the projects engage with course material and problem-pose aspects of contemporary society, thereby meeting my objectives for this application of critical simulation.

Figure 4. Halo cover image.

Halo is a tropical island paradise catering to the promises and pleasures of the resort industry (see Figure 4). The brochure flaunts, “Everyday feels like you’re on vacation.” Halo’s geography evokes More’s island of Utopus with its familiar crescent shape (see Figure 5 below), but here the similarities end. High-rise resort buildings, private bungalows, and cruise ships dot the coasts, providing a major source of revenue for the island. This revenue is distributed equitably among all citizens and ensures an ever-increasing quality of life for the entire community. In return, citizens are required to work eight hours a day and participate in town hall meetings where decisions are made by consensus. Haloans value diversity, yet discourage religion because “such ideologies … promote sexism, racism, and other common inequalities.” They also value a stress-free lifestyle and “strive to eliminate the factor of anomie that is often found within your typical western societies.”

Figure 5. A map of Halo.

Halo’s design is clearly influenced by the meme of an island utopia first established by More’s seminal text. But its emphasis on leisure—both in terms of its clever marketing scheme and its economy—draws upon different sources. In this respect, Halo finds inspiration in Thoreau’s Walden and Ellison’s “‘Repent Harlequin’,” texts that challenge the self-destructive effects of undue busyness and mindless consumerism. In this regard, Halo’s rejection of the stressful, multi-tasking, productivity-obsessed, and acquisitive lifestyle of Western consumer society constitutes its most poignant social critique. Yet, it achieves this critical distance not by copying the escapist or subversive logics of Thoreau and Ellison’s texts, respectively, but by embracing and transmogrifying the commodity logic of the globalized leisure economy. Halo is only tenable because it complies with the circuit of work and leisure that sustains the dizzying rhythm of life in modern society. Yet, it tempers its participation in this status-quo macro-economy with a micro-economy that stresses communal forms of decision-making and equitable resource distribution. Its scheme is based on the socialization of that which already exists—namely the tourist-based export economies shaped by trans-national capital and International Monetary Fund policies to service weary laborers from the more affluent nations.

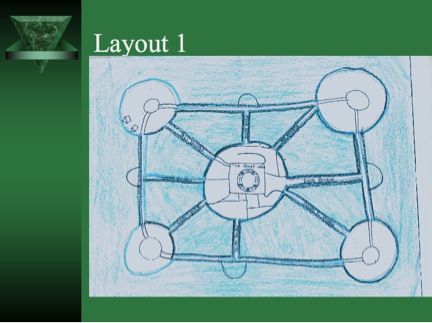

Figure 6. A diagram of Vacileeco Palati.

Part Baconian new Atlantis, part Jules Verne science fiction, Vacileeco Palati (Greek for “underwater kingdom”) is an underwater, self-propelled domed city consisting of a central forum ringed by dormitories, utilities, and farms, and navigable by trains and walking paths (see Figure 6). The city was designed to solve the twin problems of overpopulation and resource depletion by taking to the oceans in search of new resources. The inventive Palatians place a premium on discovering and circulating knowledge, and thus prefer to recruit scientists and artists. They are a communal society where all citizens are guaranteed employment, education, and healthcare, while private property and money are banned. The work week alternates between urban and agricultural labor. The political system rewards hard work with leadership roles, and the highest governing body is the “Board of the Wise.”

Vacileeco Palati is an interesting hybrid of concepts from several course texts, and also draws from Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis, which was not a course text. As a floating island, Vacileeco Palati is an interesting spin on More’s Utopus and Bacon’s Bensalem. It shares with More’s Utopia, Bacon’s New Atlantis, and Plato’s Republic a preference for knowledge and learning. The moneyless, communist economy constitutes a sharp break from modern capitalist societies and coheres with the rejection of money and private property in More, Plato, and Bellamy. In terms of the political system, the practice of rewarding hard work with leadership roles resembles Bellamy’s plan for an “industrial army” in Looking Backward, while the idea of the “Board of the Wise” recalls Plato’s “guardians” and Bacon’s “Salomon’s House.” The rotation of the workweek between urban and agricultural labor is an interesting adaptation of More’s seasonal work rotations. Meanwhile, the ringed layout of the city bears more than a passing resemblance to Howard’s “Garden City of Tomorrow.” Finally, the threatening backdrop of overpopulation and resource depletion recalls the warnings of Callenbach’s Ecotopia and Butler’s Parable of the Sower. Overall, this resourceful, hybrid design demonstrates a critical rejection of the individualism, acquisitiveness, and resource-depleting tendencies of capitalist society. Its alternative, though inspired by course texts, borrows and innovates what is desirable, rejects what is not.

Figure 7. Northern Green cover page.

Northern Californian Coastal Community, Northern Green for short, is a sovereign country founded in the year 2025 in a part of California that seceded from the United States. The mission of this eco-commune is to achieve an “ecologically sustainable, off-grid powered existence.” This central pre-occupation with sustainability is thematically expressed in the layout and imagery of its brochure (see Figure 7). To realize its mission, the Greens limit their population to 200,000, rely on renewable energy, and grow everything they need. The Greens are communitarian and democratic. Everyone is expected to work, resources are owned in common, and wealth is equally distributed using a credit card system.

The line of influence from a single course text is perhaps most pronounced with Northern Green. The placement, history, “green” ethos, and marketing aesthetic suggest a community that is clearly inspired by Callenbach’s Ecotopia and its critique of an ecologically and psychologically unsustainable industrial society. Ecotopia is similarly located on the western coast of the former United States, having seceded from the Union over various environmental and political concerns, and professing an equally “green” sensibility. Both utopias reject industrialism, consumerism, alienating urban metropolises, and the concept of infinite growth that propels capitalist societies. And yet, there are also significant differences between them. Northern Green rejects key elements of Ecotopia, such as its emphasis on decentralized, small crafts production, and the continuation of racial segregation. Rather than slavishly imitate Ecotopia, Northern Green turns to other course texts for inspiration. The equal credit system recalls the credit system from Looking Backward, while the idea of garden cities references Howard’s early designs for suburbia.

Figure 8. Guavaland’s Myspace page.

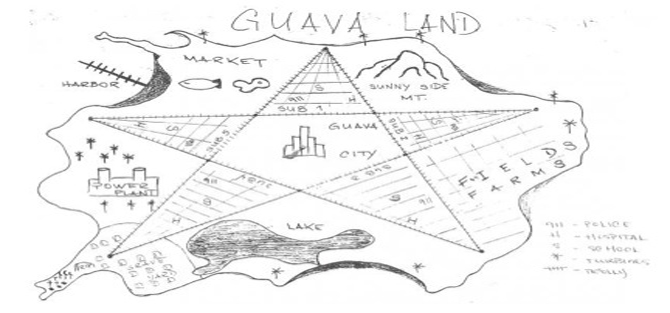

The tropical island utopia, Guavaland, is as hip as its Myspace page. This inventive team of utopian engineers decided to advertise their community on Myspace, where visitors are greeted by automated steel pan music and lush, tropical images (see Figure 8). Guavaland blends natural beauty with technological sophistication, boasting a futuristic steel-and-glass metropolis bursting out of a pristine jungle. Guavaland is a commonwealth comprised of five villages and a central city, Guava City, which form a pentagram design (see Figure 9). Wind turbines ring the coastline and trolley lines connect each village. The Guavalanders value cooperation over individualism and enjoy free education and healthcare. Their major industry is agriculture and they believe in “natural living.” They seek “hardworking men and women” who “are willing to make sacrifices for the good of the community” and who “are ready and willing to leave the fast-paced life behind and enjoy the splendor of the easy-going life.”

Figure 9. A map of Guavaland.

Guavaland is similar to Halo in its rejection of the “fast-paced life” that plagues many modern industrial and post-industrial societies. However, it rejects becoming inscribed within the globalized economics of the commodified leisure industry that Halo occupies. It embraces, instead, an agrarian economy that emphasizes self-sufficiency, natural living, and renewable resources. In these respects, Guavaland bears more than a passing resemblance to Ecotopia. But it also borrows from other sources. For instance, the commonwealth system and communitarian values evoke More’s Utopia, while the pentagram layout of its suburban villages is a novel interpretation of Howard’s garden city design. The science-fiction feel and look of Guava City seems misplaced in this communitarian eco-village. But it also promises that nature and technology can successfully co-exist.

Figure 10. Phoenix rising.

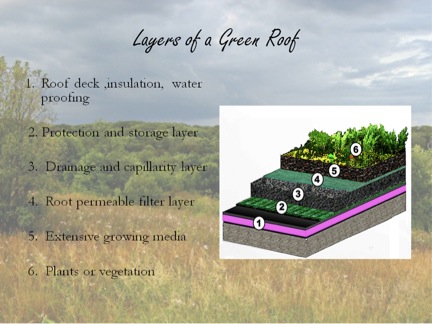

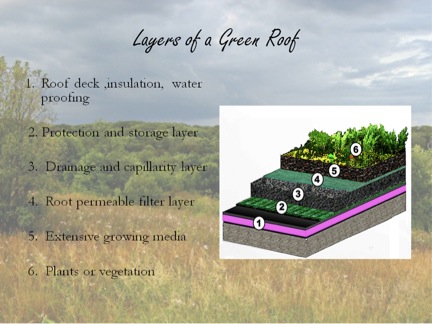

Phoenix’s fiery phoenix imagery says it all (see Figure 10). It is a community of survivors intent on rebuilding human civilization after the predations of modern industrial society unleashed a tsunami of global climate change, famine, pandemic, and war. The brochure features a quote from Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Emile (1762) that neatly sums up Phoenix’s philosophy: “It is in man’s heart that the life of nature’s spectacle exists; to see it one must feel it.” The quote encapsulates Phoenix’s rejection of modern industrial society in favor of a back-to-nature approach to life that favors sustainability and personal freedom. The Phoenixans are a libertarian society with communal traditions and a commitment to lo-tech (there is no electricity), environmentally friendly technologies. Each citizen is an individual freeholder who pursues a trade and barters for other goods and services. The society is governed by a council of elders and all citizens are expected to obey a central constitution called the “Code of Conduct,” which includes laws prohibiting violence and intolerance, regulations for “green roofs” (see Figure 11), protections for the right to free education and healthcare, and the requirement that each citizen donate 20 percent of their labor to the community.

Figure 11. Green roofs are mandatory for all Phoenixian domiciles. This design is intended to provide several benefits: it extends the lifespan of the roof, provides food, purifies the air, and increases biodiversity.

Phoenix differs from the other intentional communities in the depth of its origin narrative. After the collapse of civilization into bloodthirsty bands of nomads and scavengers, an oracle-like woman named Themis brought together a rag-tag group of survivors and resettled what is now North Manitou Island in Lake Michigan (now transformed by global warming into a temperate environment), renaming it “Avani” (Sanskrit for “Earth”). In 2059, they founded the community of Phoenix to symbolize the fact that they were “rising from the ashes of their predecessors.” Three generations later, Phoenix numbers 500 members and growing.

Phoenix’s design incorporates elements from several course texts. The emphasis on green technologies and barter economies suggests a clear line of influence from Callenbach’s Ecotopia, while the council of elders is reminiscent of the respect accorded to elders in Gilman’s Herland. Yet, the most striking similarity is with Butler’s Parable of the Sower. The Parable is similarly a post-apocalyptic tale about the trials and tribulations of a rag-tag bunch of survivors who must brave a “Mad Max”-like landscape to arrive at a safe haven where they can start over. The oracular Themis, whose name is taken from the Greek goddess of law and order valued above all for her good counsel, is an allusion to Butler’s spunky prophet-like protagonist, Lauren Olamina, who leads these survivors and inspires them with her new religion, Earthseed. In the end, they found a community, Acorn, in the Parable of the Sower, which promises to be the seed of a new society. Similarly, the back-to-nature vision of the oracle Themis attracts followers who eventually come together to plant the seed of a new society, Phoenix. Both narratives are examples of what Lyman Tower Sargent has called critical dystopia, a vision that “holds out hope that the dystopia can be overcome and replaced with a eutopia” (Sargent 2001, 222). Phoenix thus combines an apocalyptic vision that critiques what is wrong with contemporary society—from our overreliance on fossil fuels to our exploitative relationships with the Earth and each other—while pointing the way to a compassionate alternative.

Debriefing Utopia

I decided to follow up the students’ final presentations with an exit survey to have them debrief about their experience with the critical simulation. I asked the students: Did it help you to improve your understanding of course material? Did your idea of utopia change after taking this course? Not everyone completed the survey, but the responses I did receive suggest the critical simulation was a successful “fourth leg” to the more traditional pedagogical elements of literature courses, namely reading, writing, and discussion, which were also utilized by this course.

The responses to the first question—whether the critical simulation improved one’s understanding of the course material—were positive and fairly uniform in nature. One student responded:

By putting ourselves as planners of our utopia and facing the challenges posed by the professor, I was able to change my mindset into actually thinking about how I would change the world and then this was contrasted by the authors’ ideas on how to change the world. It is definitely a key part of the class, and the discussions within my group allowed me to better understand everything and to get different views.

Another stated:

The group project was very effective for helping to understand what we were supposed to get out of this course. The reason why it was so effective was due to the fact that we had to put ourselves in the realm that these authors were to attain our understanding of how complicated and visionary it is to have to design a utopia.

The comments highlight the benefits of situated learning that all simulations provide. By putting themselves “in the realm” of the authors they were reading, the critical simulation afforded them a better understanding of the conventions and complexities of utopian thought and production.

The second question—whether the course altered students’ visions of utopia—really got to the core of what I hoped to accomplish with the critical simulation. If one goal of utopia is “the education of desire” (Thompson 1977, 791), then by measuring how much a student’s thinking about utopia had changed from his or her initial conception of it at the beginning of the semester, I would be able to appraise how well the critical simulation had provoked a critical re-examination of the domains (e.g., government, economy, ecology, etc.) and themes (e.g., justice, equality, harmony, etc.) that are the central pre-occupation of utopian desire.

Unfortunately, the responses to this question were varied and inconclusive. One student reported a high degree of change: “I came to understand that it is through individual mindfulness that a utopian society is found. That differs from my initial idea of just communality. Utopia is only possible if every member of the society is actively involved in changing it or creating it.” On the other hand, another student reported little or no change: “I seem to be very consistent when it comes to what my initial thoughts of my utopia were and what [it] came out to be.” A third student had a mixed reaction: “[My view of utopia] didn’t change that much, it more so evolved into something much richer and more specific.”

Nevertheless, when these responses are viewed holistically in conjunction with the overall enthusiasm with which the students participated in the semester-long critical simulation and the depth of thinking in the final brochures they produced, I think this experiment with critical simulation speaks in favor of its incorporation within the set of go-to pedagogical techniques available to those of us interested in promoting critical thinking in our classes. I don’t think this addition will fundamentally change how we teach. Rather, if I may paraphrase my student, I think it will help us to evolve our practice into something “much richer and more specific.”

That said, in reflecting critically on my own praxis and how I might revise it the next time around, I think an interesting and necessary turn-of-the-screw would be to have students conclude the semester by writing critical reflections on their own utopias in which they interrogate, as I did above, their engagement with social themes and course material. This would involve asking them to speculate on the possible dystopian tendencies and outcomes intrinsic to their utopian designs and to the practice of utopia generally. Is utopia an inflexible blueprint for an ideal state that ultimately leads to totalitarianism as some critics have asserted (Popper 1994), or is it fundamentally a “principle of hope” without which humanity is lost (Bloch 1986)? This reflective assignment may help to prod those students who registered little or no change from their initial frame to critically re-examine their held beliefs and venture new ones.

Yet, my most pressing concern has less to do with the shortcomings of this experiment with critical simulation than with its successes. What happens to those students who succeed in critically re-examining the real-world domains they are ostensibly being prepared to occupy once they leave the university? How does a student actualize his or her new utopian desires once the semester is over and the classroom is exited? This paradox was keenly felt by one student, who responded in the survey, “Maybe one day I can change the world with my ideas and arguments. Until then, I’ll just continue on with my education and continue to dream of the future.”

The student’s comment points to the problem of agency that arises when simulation inside the classroom does not lead to comfortable assimilation outside the classroom, but instead provokes utopian “social dreaming” that arouses the sweet yet unsettling “desire for a better way of being.” The perceived disconnect between what is desired and what is possible risks producing the “miniutopia” that Bowles and Gintis and Stanford warn against. Yet, if my critical simulation created a miniutopia, the problem, in this case, is not so much that it left students “lacking a political understanding of their predicament” as Bowles and Gintis fear, but that the students lack a ready-made outlet for transformative practice with which to apply the political understanding actually garnered from the experience of simulating utopia. As a result, the risk of critical simulation is that the newfound utopian desire it produces may remain confined to the utopian no-place of learning, where it is subject to indefinite deferral and deformation.

This experiment with critical simulation raises a number of important discoveries and questions for educators interested in teaching critical thinking in any discipline. It demonstrates that critical simulations are engaging activities with the potential to situate meaning in ways that foster students’ critical thinking while enhancing comprehension of course material. As such, they provide a valuable supplement to standard teaching practices, such as reading, writing, and discussion. Though they require significant forethought, iteration, and time to develop, and sometimes result in minor setbacks as evidenced by my failure to incorporate specialized roles, these requirements and difficulties are true for effective teaching strategies in general and should not deter one from investigating this option. Furthermore, the replay factor alone may more than account for the initial investment of time and effort. Although the problem of where to channel the unsettling utopian desire for change unleashed by this technique remains open, it also highlights a challenge facing all educators interested in teaching critical thinking: how to bridge the divide between the space of practice and social dreaming carefully cultivated in the classroom, and the space of praxis and social change that awaits outside. In the end, I am content to have raised the utopian itch. For if, as Oscar Wilde famously proclaimed, “Progress is the realisation of Utopias,” then by simulating utopia with my students I have at least prepared them to decide what should come next.

Bibliography

Alexander, Jonathan. 2009. “Gaming, Student Literacies, and the Composition Classroom: Some Possibilities for Transformation.” College Composition and Communication 61 (1): 35-63. OCLC 5104742867.

Ansoms, An and Sara Greenen. 2012. “BUILDING TIES IN A STRATIFIED SOCIETY: A Social Networking Simulation Game.” Simulation & Gaming 43 (5): 673-85. OCLC 869959620.

Bachen, Christine M., Pedro F. Hernández-Ramos, and Chad Raphael. 2012. “Simulating REAL LIVES: Promoting Global Empathy and Interest in Learning through Simulation Games.” Simulation & Gaming 43 (4): 437-60. OCLC 811568172.

Barak, Azy, Cathy Engle, Liora Katzir, and William A. Fisher. 1987. “Increasing the Level of Empathic Understanding by Means of a Game.” Simulation & Gaming 18 (4): 458-70. OCLC 4651870131.

Bernstein, Jeffrey L. and Deborah S. Meizlish. 2003. “Becoming Congress: A Longitudinal Study of the Civic Engagement Implications of a Classroom Simulation.” Simulation & Gaming 34 (2): 198-219. OCLC 437644078.

Bloch, Ernst. 1986. The Principle of Hope. 3 vols. Translated by Neville Plaice, Stephen Plaice, and Paul Knight. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. OCLC 742568955.

Bowles, Samuel and Herbert Gintis. 1976. Schooling in Capitalist America: Education Reform and the Contradictions of Economic Life. New York: Basic Books. OCLC 1602016.

Brewbaker, James M. 1972. “Simulation Games and the English Teacher.” The English Journal 61 (1): 104-09, 112. OCLC 1329259.

Cazden, Courtney, Bill Cope, Norman Fairclough, Jim Gee, Mary Kalantzis, Gunther Kress, Allan Luke, Carmen Luke, Sarah Michaels, and Martin Nakata. 1996. “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures.” Harvard Educational Review 66 (1): 60-92. OCLC 425954250.

Colby, Rebekah Shultz and Richard Colby. 2008. “A Pedagogy of Play: Integrating Computer Games into the Writing Classroom.” Computers and Composition 25: 300-12. OCLC 280989052.

Colby, Richard, Matthew S. S. Johnson, and Rebekah Shultz Colby, eds. 2013. Rhetoric/Composition/Play through Video Games: Reshaping Theory and Practice of Writing. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. OCLC 818732780.

Coté, Mark, Richard J.F. Day, and Greig de Peuter. 2007. “Introduction: What is Utopian Pedagogy?” In Utopian Pedagogy: Radical Experiments against Neoliberal Globalization, edited by Mark Coté, Richard J.F. Day, and Greig de Peuter, 3-19. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. OCLC 63125382.

Crocco, Francesco. 2011. “Critical Gaming Pedagogy.” Radical Teacher 91 (Fall): 26-41. OCLC 755910754.

Dundes, Lauren and Roxanna Harlow. 2005. “Illustrating the Nature of Social Inequality with the Simulation Star Power.” Teaching Sociology 33: 32-43. OCLC 662695047.

Fisher, Edith M. 2008. “USA Stratified Monopoly: A Simulation Game about Social Class Stratification.” Teaching Sociology 36: 272-82. OCLC 662692592.

Freire, Paulo. 2002. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum. OCLC 43929806.

Gaber, John. 2007. “Simulating Planning: SimCity as a Pedagogical Tool.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 27: 113-21. OCLC 4652701608.

Gee, James P. 2004. Situated Language and Learning: A Critique of Traditional Schooling. New York: Routledge. OCLC 56026684.

—. 2007. What Video Games Have to Teach Us About Learning and Literacy. Rev. ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. OCLC 172569526.

Gilliom, M. Eugene. 1974. “Trends in Simulation.” The High School Journal 57 (7): 265-72. OCLC 10517405.

Hertel, John P. and Barbara J. Millis. 2002. Using Simulations to Promote Learning in Higher Education. Sterling, VA: Stylus. OCLC 56609659.

Holquist, Michael. 1968. “How to Play Utopia.” Yale French Studies 41: 106-23. OCLC 1770272.

Kovalik, Doina L. and Ludovik M. Kovalik. 2007. “Language Simulations: The Blending Space for Writing and Critical Thinking.” Simulation & Gaming 38 (3): 310-22. OCLC 611132545.

Krause, Tim. 2010. “Using Simulation to Teach Project Management in the Professional Writing Classroom.” The Writing Instructor. Accessed February 4, 2014. http://www.writinginstructor.com/krause. OCLC 662675048.

Kroll, Barry M. 1986. “Explaining How to Play a Game: The Development of Informative Writing Skills.” Written Communication 3 (2): 195-218. OCLC 425403333.

Lee, Joey J., Pinar Ceyhan, William Jordan-Cooley, and Woonhee Sung. 2013. “GREENIFY: A Real-World Action Game for Climate Change Education.” Simulation & Gaming 44 (2-3): 349-65. OCLC 4948331468.

Levitas, Ruth. 1990. The Concept of Utopia. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse UP. OCLC 21975950.

Martin, David S. 1979. “Five Simulation Games in the Social Sciences.” Simulation & Gaming 10 (3): 331-49. OCLC 41552194.

Mead, Corey. 2013. War Play: Video Games and the Future of Armed Conflict. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. OCLC 828890722.

McCall, Jeremiah. 2011. Gaming the Past: Using Video Games to Teach Secondary History. New York: Routledge. OCLC 654316727.

McCann, Thomas M. 1996. “A Pioneer Simulation for Writing and for the Study of Literature.” The English Journal 85 (3): 62-67. OCLC 425949308.

Nash, Gail. 2007. “Conference Simulation in an English Composition Course.” Simulation & Gaming 38 (3): 332-43. OCLC 639027147.

Norris, Dawn R. 2013. “Beat the Bourgeoisie: A Social Class Inequality and Mobility Simulation Game.” Teaching Sociology 41 (4): 334-45. OCLC 5128212527.

Popper, Karl. 1994. The Open Society and Its Enemies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. OCLC 177688.

Raphael, Chad, Christine Bachen, Kathleen M. Lynn, Jessica Baldwin-Philippi, and Kristen A. McKee. 2010. “Games for Civic Learning: A Conceptual Framework and Agenda for Research and Design.” Games and Culture 5 (2): 199-235. OCLC 615277608.

Ricoeur, Paul. 1986. Lectures on Ideology and Utopia. Edited by George H. Taylor. New York: Columbia UP. OCLC 13357978.

Saliés, Tânia Gastão. 2002. “Simulation/Gaming in the EAP Writing Class: Benefits and Drawbacks.” Simulation & Gaming 33 (3): 316-29. OCLC 425758225.

—. 2007. “Reflections on the GUN CONTROL Simulation: Pedagogical Implications for EAP Writing Classes.” Simulation & Gaming 38 (4): 569-80. OCLC 611132505.

Sargent, Lyman T. 2001. “US Eutopias in the 1980s and 1990s: Self-Fashioning in a World of Multiple Identities.” In Utopianism/Literary Utopias and National Cultural Identities: A Comparative Perspective, edited by Paola Spinozzi, 221-32. Bologna: COTEPRA/University of Bologna. OCLC 494699098.

—. 2010. Utopianism: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford UP. OCLC 624411960.

Schulzke, Marcus. 2013. “Using Video Games to Think about Distributive Justice.” Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy 2: 1-19. Accessed February 4, 2014. https://jitp.commons.gc.cuny.edu/using-video-games-to-think-about-distributive-justice/.

Shaffer, David W. 2005. “Epistemic Games.” Innovate 1 (6): n.p. Accessed May 5, 2015. http://www.taqniyat.com/cms_pdf/Epistemic_Games.pdf. OCLC 593833847.

Shor, Ira. 1992. Empowering Education: Critical Teaching for Social Change. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. OCLC 25412216.

—. 1996. When Students Have Power: Negotiating Authority in a Critical Pedagogy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. OCLC 34558888.

Simpson, Joseph M. and Vicky L. Elias. 2011. “Choices and Chances: The Sociology Role-playing Game—The Sociological Imagination in Practice.” Teaching Sociology 39 (1) 42-56. OCLC 5544663062.

Sloan, Gary. 1978. “Writing as Game.” The English Journal 67 (8): 44-47. OCLC 425888001.

Stanford, Nichole. E. 2012. “Teaching Toward Utopia: Complainstorming and the Pitfalls of Utopian Education.” Unpublished paper, 1-15.

Sterman, John, Travis Franck, Thomas Fiddaman, Andrew Jones, Stephanie McCauley, Philip Rice, Elizabeth Sawin, Lori Siegel, and Juliette N. Rooney-Varga. 2014. “WORLD CLIMATE: A Role-Play Simulation of Climate Negotiations.” Simulation & Gaming January 9, 2014: 1-35. Accessed February 4, 2014. doi: 10.1177/1046878113514935. OCLC 5525873867.

Thatcher, Donald C. and M. June Robinson. 1990. “The Unemployment Game.” Simulation & Gaming 21 (3): 284-90. OCLC 20550385.

Thompson, E.P. 1977. William Morris: Romantic to Revolutionary. New York: Pantheon Books. OCLC 2967708.

Torres, Maruja and Joseli Macedo. 2000. “Learning Sustainable Development with a New Simulation Game.” Simulation & Gaming 31 (1): 119-26. OCLC 358567532.

Troyka, Lynn Quitman and Jerrold Nudelman. 1975. Taking Action: Writing, Reading, Speaking, and Listening through Simulation-Games. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. OCLC 1093551.

Troyka, Lynn Quitman. 1974. A Study of the Effects of Simulation-gaming on Expository Prose Competence of College Remedial English Composition Students. Doctoral dissertation, New York University, New York. OCLC 5665947.

Wilde, Oscar. 1910. The Soul of Man Under Socialism. Boston: John W. Luce. OCLC 5430379.

About the Author

Dr. Francesco Crocco is an Associate Professor at Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC) of The City University of New York (CUNY). He received his Ph.D. in English from the CUNY Graduate Center and has published several articles and a book on British Romantic poetry and nationalism. His recent scholarship focuses on game-based learning, gamification, and utopian studies. With funding from a Title V grant, he co-designed Levelfly, a gamified learning management system and social network that was piloted at BMCC. He is currently a PI on an NSF-funded project to develop a video-game-based curriculum to improve math remediation for STEM majors. His forthcoming publications include an edited volume on the broad cultural impact of role-playing games and articles theorizing representations of work and play in utopian and dystopian literature and films. Dr. Crocco is also the co-founder of the CUNY Games Network and coordinator of the CUNY Games Festival, an annual national conference on game-based learning in higher education.