Introduction

Much has been written of what lies inside (and outside) the digital humanities (DH). A fitting example might be the annual Day of DH, when hundreds of “DHers” (digital humanists) write about what they do and how they define the field (see https://twitter.com/dayofdh). Read enough of their stories and certain themes and patterns may emerge, but difference and pluralism will abound. More formal attempts to define the field are not hard to find—there is an entire anthology devoted to the subject (Terras, Nyhan, and Vanhoutte 2013)—and others have approached DH by studying its locations (Zorich 2008; Prescott 2016), its members (Grandjean 2014a, 2014b, 2015), their communication patterns (Ross et al. 2011; Quan-Haase, Martin, and McCay-Peet 2015), conference submissions (Weingart 2016), and so forth.

A small but important subset of research looks at teaching and learning as a lens through which to view the field. Existing studies have examined course syllabi (Terras 2006; Spiro 2011) and the development of specific programs and curricula (Rockwell 1999; Siemens 2001; Sinclair 2001; Unsworth 2001; Unsworth and Butler 2001; Drucker, Unsworth, and Laue 2002; Sinclair & Gouglas 2002; McCarty 2012; Smith 2014). In addition, there are pedagogical discussions about what should be taught in DH (Hockey 1986, 2001; Mahony & Pierazzo 2002; Clement 2012) and its broader relationship to technology, the humanities, and higher education (Brier 2012; Liu 2012; Waltzer 2012).

This study adds to the literature on teaching and learning by presenting a survey of existing degree and certificate programs in DH. While these programs are only part of the activities that make up the broader world of DH, they provide a formal view of training in the field and, by extension, of the field itself. Additionally, they reflect the public face of DH at their institutions, both to potential students and to faculty and administrators outside of DH. By studying the requirements of these programs (especially required coursework), we explore the activities that make up DH, at least to the extent that they are systematically taught and represented to students during admissions and recruitment, as well as where DH programs position themselves within and across the subject boundaries of their institutions. These activities speak to broader skills and methods at play in DH, as well as some important silences. They also provide an empirical perspective on pedagogical debates, particularly the attention paid to theory and critical reflection

Background

Melissa Terras (2006) was the first to point to the utility of education studies in approaching the digital humanities (or what she then called “humanities computing”). In the broadest sense, Terras distinguishes between subjects, which are usually associated with academic departments and defined by “a set of core theories and techniques to be taught” (230), and disciplines, which lack departmental status yet still have their own identities, cultural attributes, communities of practice, heroes, idols, and mythology. After analyzing four university courses in humanities computing, Terras examines other aspects of the community such as its associations, journals, discussion groups, and conference submissions. She concludes that humanities computing is a discipline, although not yet a subject: “the community exists, and functions, and has found a way to continue disseminating its knowledge and encouraging others into the community without the institutionalization of the subject” (242). Terras notes that humanities computing scholars, lacking prescribed activities, have freedom in developing their own research and career paths. She remains curious, however, about the “hidden curriculum” of the field at a time when few formal programs yet existed.

Following Terras, Lisa Spiro (2011) takes up this study of the “hidden curriculum” by collecting and analyzing 134 English-language syllabi from DH courses offered between 2006–2011. While some of these courses were offered in DH departments (16, 11.9%), most were drawn from other disciplines, including English, history, media studies, interdisciplinary studies, library and information science, computer science, rhetoric and composition, visual studies, communication, anthropology, and philosophy. Classics, linguistics, and other languages were missing. Spiro analyzes the assignments, readings, media types, key concepts, and technologies covered in these courses, finding (among other things) that DH courses often link theory to practice; involve collaborative work on projects; engage in social media such as blogging or Twitter; focus not only on text but also on video, audio, images, games, maps, simulation, and 3D modeling; and reflect contemporary issues such as data and databases, openness and copyright, networks and networking, and interaction. Finally, Spiro presents a list of terms she expected to see more often in these syllabi, including “argument,” “statistics,” “programming,” “representation,” “interpretation,” “accessibility,” “sustainability,” and “algorithmic.”

These two studies form the broad picture of DH education. More recent studies have taken up DH teaching and learning within particular contexts, such as community colleges (McGrail 2016), colleges of liberal arts and science (Alexander & Davis 2012; Buurma & Levine 2016), graduate education (Selisker 2016), libraries (Rosenblum, et al., 2016; Varner 2016; Vedantham & Porter 2016) and library and information science education (Senchyne 2016), and the public sphere (Brennan 2016; Hsu 2016). These accounts stress common structural challenges and opportunities across these contexts. In particular, many underscore assumptions made about and within DH, including access to technology, institutional resources, and background literacies. In addition, many activities in these contexts fall outside of formal degrees and programs or even classroom learning, demonstrating the variety of spaces in which DH may be taught and trained.

Other accounts have drawn the deep picture of DH education by examining the development of programs and courses at specific institutions, such as McMaster University (Rockwell 1999), University of Virginia (Unsworth 2001; Unsworth and Butler 2001; Drucker, Unsworth, and Laue 2002), University of Alberta (Sinclair & Gouglas 2002), King’s College London (McCarty 2012), and Wilfrid Laurier University (Smith 2014), among others. Abstracts from “The Humanities Computing Curriculum / The Computing Curriculum in the Arts and Humanities” Conference in 2001 contain references to various institutions (Siemens 2001), as does a subsequent report on the conference (Sinclair 2001). Not surprisingly, these accounts often focus on the histories and peculiarities of each institution, a “localization” that Knight (2011) regards as necessary in DH.

Our study takes a program-based approach to studying teaching and learning in DH. While formal programs represent only a portion of the entire DH curricula, they are important in several respects: First, they reflect intentional groupings of courses, concepts, skills, methods, techniques, and so on. As such, they purport to represent the field in its broadest strokes rather than more specialized portions of it (with the exception of programs offered in specific areas, such as book history and DH). Second, these programs, under the aegis of awarding institutions and larger accrediting bodies, are responsible for declaring explicit learning outcomes of their graduates, often including required courses. These requirements form one picture of what all DHers are expected to know upon graduation (at a certain level), and this changing spectrum of competencies presumably reflects corresponding changes in the field over time. Third, formal DH programs organize teaching, research, and professional development in the field; they are channels through which material and symbolic capital flow, making them responsible, in no small part, for shaping the field itself. Finally, these programs, their requirements, and coursework are one way—perhaps the primary way—in which prospective students encounter the field and make choices about whether to enroll in a DH program and, if so, which one. These programs are also consulted by faculty and administrators developing new programs at their own institutions, both for common competencies and for distinguishing features of particular programs.

In addition to helping define the field, a study of formal DH programs also contributes to the dialogue around pedagogy in the field. Hockey, for example, has long wondered whether programming should be taught (1986) and asks, “How far can the need for analytical and critical thinking in the humanities be reconciled with the practical orientation of much work in humanities computing?” (2001). Also skeptical of mere technological skills, Simon Mahony and Elena Pierazzo (2002) argue for teaching methodologies or “ways of thinking” in DH. Tanya Clement examines multiliteracies in DH (e.g., critical thinking, commitment, community, and play), which help to push the field beyond “training” to “a pursuit that enables all students to ask valuable and productive questions that make for ‘a life worth living’” (2012, 372).

Others have called on DH to engage more fully in critical reflection, especially in relation to technology and the role of the humanities in higher education. Alan Liu notes that much DH work has failed to consider “the relation of the whole digital juggernaut to the new world order,” eschewing even clichéd topics such as “the digital divide,” “surveillance,” “privacy,” and “copyright” (2012, 491). Steve Brier (2012) points out that teaching and learning are an afterthought to many DHers, a lacuna that misses the radical potential of DH for transforming teaching and professional development. Luke Walzer (2012) observes that DH has done little to help protect and reconceptualize the role of the humanities in higher education, long under threat from austerity measures and perceived uselessness in the neoliberal academy (Mowitt 2012).

These and other concerns point to longstanding questions about the proper balance of technological skills and critical reflection in DH. While a study of existing DH programs cannot address the value of critical reflection, it can report on the presence (or absence) of such reflection in required coursework and program outcomes. Thus, it is part of a critical reflection on the field as it stands now, how it is taught to current students, and how such training will shape the future of the field. It can also speak to common learning experiences within DH (e.g., fieldwork, capstones), as well as disciplinary connections, particularly in program electives. These findings, together with our more general findings about DH activities, give pause to consider what is represented in, emphasized by, and omitted from the field at its most explicit levels of educational training.

Methods

This study involved collection of data about DH programs, coding descriptions of programs and courses using a controlled vocabulary, and analysis and visualization.

Data Collection

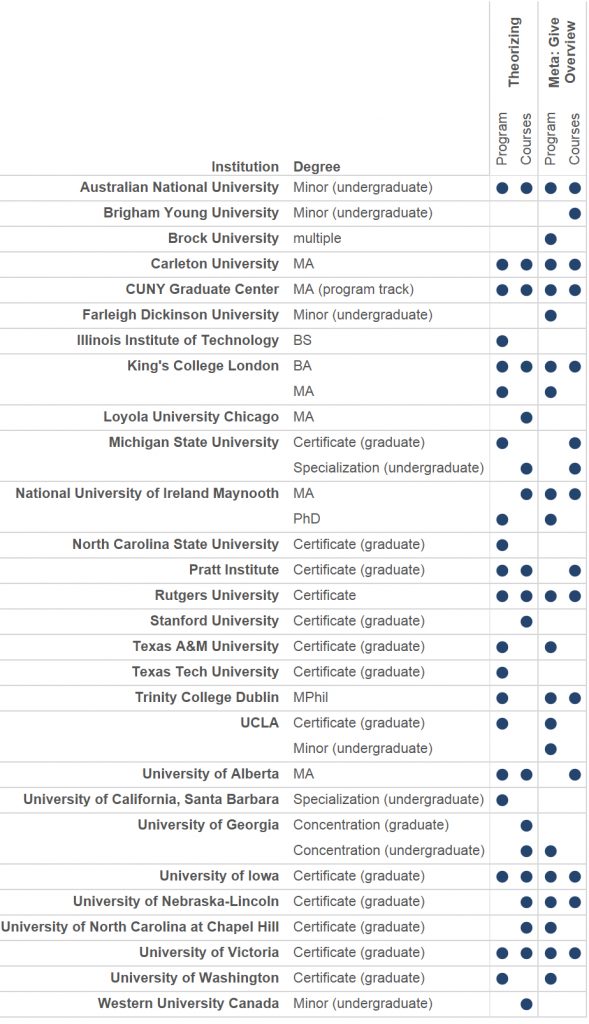

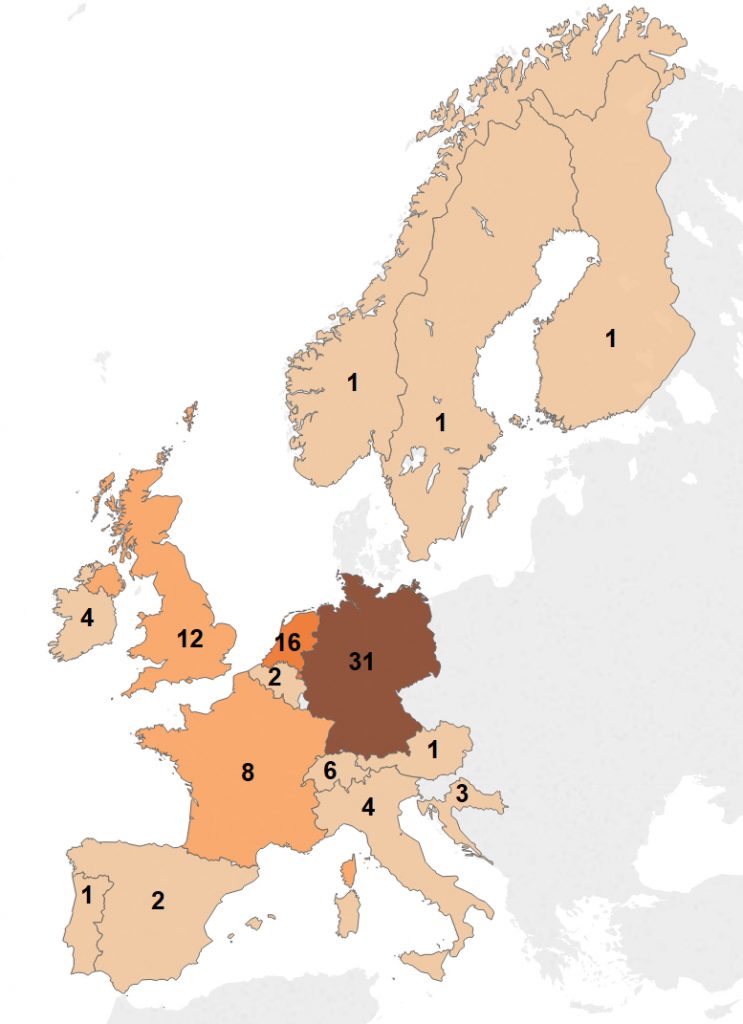

We compiled a list of 37 DH programs active in 2015 (see Appendix A), drawn from listings in the field (UCLA Center for Digital Humanities 2015; Clement 2015), background literature, and web searches (e.g., “digital humanities masters”). In addition to degrees and certificates, we included minors and concentrations that have formal requirements and coursework, since these programs can be seen as co-issuing degrees with major areas of study and as inflecting those areas in significant ways. We did not include digital arts or emerging media programs in which humanities content was not the central focus of inquiry. In a few cases, the listings or literature mentioned programs that could not be found online, but we determined that these instances were not extant programs—some were initiatives or centers misdescribed, others were programs in planning or simply collections of courses with no formal requirements—and thus fell outside the scope of this study. We also asked for the names of additional programs at a conference presentation, in personal emails, and on Twitter. Because our sources and searches are all English-language, the list of programs we collected are all programs taught in Anglophone countries. This limits what we can say about global DH.

For each program, we made a PDF of the webpage on which its description appears, along with a plain text file of the description. We recorded the URL of each program and information about its title; description; institution; school, division, or department; level (graduate or undergraduate); type (degree or otherwise); year founded; curriculum (total credits, number and list of required and elective courses); and references to independent research, fieldwork, and final deliverables. After identifying any required courses for each program, we looked up descriptions of those courses in the institution’s course catalog and recorded them in a spreadsheet.

Coding and Intercoder Agreement

To analyze the topics covered by programs and required courses, we applied the Taxonomy of Digital Research Activities in the Humanities (TaDiRAH 2014a), which attempts to capture the “scholarly primitives” of the field (Perkins et al. 2014). Unsworth (2000) describes these primitives as “basic functions common to scholarly activities across disciplines, over time, and independent of theoretical orientation,” obvious enough to be “self-understood,” and his preliminary list includes ‘Discovering’, ‘Annotating’, ‘Comparing’, ‘Referring’, ‘Sampling’, ‘Illustrating’, and ‘Representing’.

We doubt that any word—or classification system—works in this way. Language is always a reflection of culture and society, and with that comes questions of power, discipline/ing, and field background. Moreover, term meaning shifts over time and across locations. Nevertheless, we believe classification schema can be useful in organizing and analyzing information, and that is the spirit in which we employ TaDiRAH here.

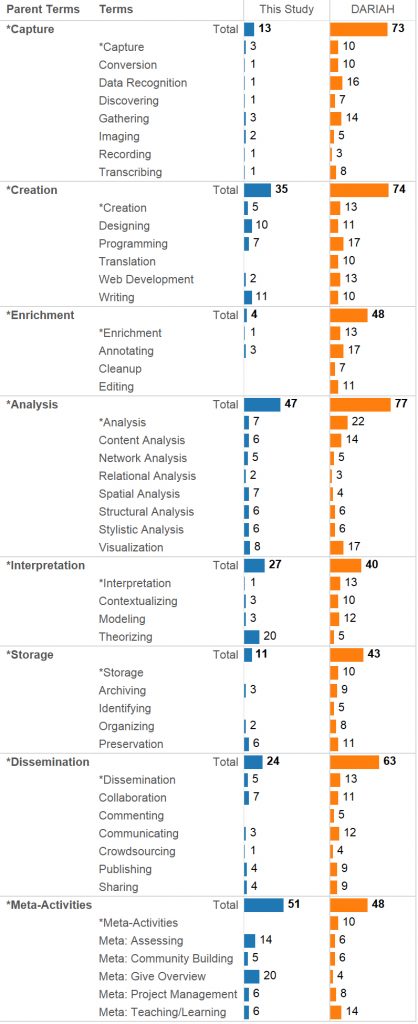

TaDiRAH is one of several classification schema in DH and is itself based on three prior sources: the arts-humanities.net taxonomy of DH projects, tools, centers, and other resources; the categories and tags originally used by the DiRT (Digital Research Tools) Directory (2014); and headings from “Doing Digital Humanities,” a Zotero bibliography of DH literature (2014) created by the Digital Research Infrastructure for Arts and Humanities (DARIAH). The TaDiRAH version used in this study (v. 0.5.1) also included two rounds of community feedback and subsequent revisions (Dombrowski and Perkins 2014). TaDiRAH’s controlled vocabulary terms are arranged into three broad categories: activities, objects, and techniques. Only activities terms were used in this study because the other terms lack definitions, making them subject to greater variance in interpretation. TaDiRAH contains forty activities terms organized into eight parent terms (‘Capture’, ‘Creation’, ‘Enrichment’, ‘Analysis’, ‘Interpretation’, ‘Storage’, ‘Dissemination’, and ‘Meta-Activities’).

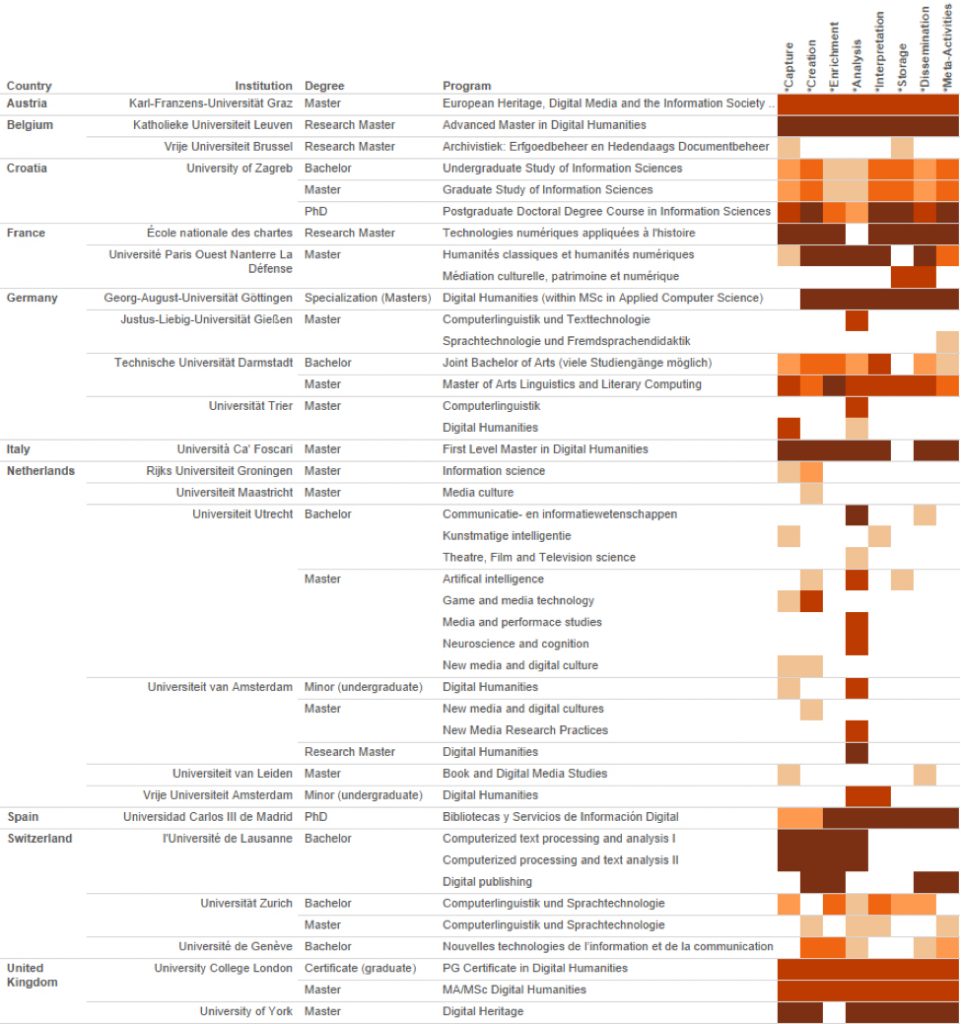

TaDiRAH was built in conversation with a similar project at DARIAH called the Network for Digital Methods in the Arts and Humanities (NeDiMAH) and later incorporated into that project (2015). NeDiMAH’s Methods Ontology (NeMO) contains 160 activities terms organized into five broad categories (‘Acquiring’, ‘Communicating’, ‘Conceiving’, ‘Processing’, ‘Seeking’) and is often more granular than TaDiRAH (e.g., ‘Curating’, ‘Emulating’, ‘Migrating’, ‘Storing’, and ‘Versioning’ rather than simply ‘Preservation’). While NeMO may have other applications, we believe it is too large to be used in this study. There are many cases in which programs or even course descriptions are not as detailed as NeMO in their language, and even the forty-eight TaDiRAH terms proved difficult to apply because of their number and complexity. In addition, TaDiRAH has been applied in DARIAH’s DH Course Registry of European programs, permitting some comparisons between those programs and the ones studied here.

In this study, a term was applied to a program/course description whenever explicit evidence was found that students completing the program or course would be guaranteed to undertake the activities explicitly described in that term’s definition. In other words, we coded for minimum competencies that someone would have after completing a program or course. The narrowest term was applied whenever possible, and multiple terms could be applied to the same description (and, in most cases, were). For example, a reference to book digitization would be coded as ‘Imaging’:

Imaging refers to the capture of texts, images, artefacts or spatial formations using optical means of capture. Imaging can be made in 2D or 3D, using various means (light, laser, infrared, ultrasound). Imaging usually does not lead to the identification of discrete semantic or structural units in the data, such as words or musical notes, which is something DataRecognition accomplishes. Imaging also includes scanning and digital photography.

If there was further mention of OCR (optical character recognition), that would be coded as ‘DataRecognition’ and so on. To take another example, a reference to visualization and other forms of analysis would be coded both as ‘Visualization’ and as its parent term, ‘Analysis’, if no more specific child terms could be identified.

In some cases, descriptions would provide a broad list of activities happening somewhere across a program or course but not guaranteed for all students completing that program or course (e.g., “Through our practicum component, students can acquire hands-on experience with innovative tools for the computational analysis of cultural texts, and gain exposure to new methods for analyzing social movements and communities enabled by new media networks.”). In these cases, we looked for further evidence before applying a term to that description.

Students may also acquire specialty in a variety of areas, but this study is focused on what is learned in common by any student who completes a specific DH program or course; as such, we coded only cases of requirements and common experiences. For the same reason, we coded only required courses, not electives. Finally, we coded programs and required courses separately to analyze whether there was any difference in stated activities at these two levels.

To test intercoder agreement, we selected three program descriptions at random and applied TaDiRAH terms to each. In only a handful of cases did all three of us agree on our term assignments. We attribute this low level of agreement to the large number of activities terms in TaDiRAH, the complexity of program/course descriptions, questions of scope (whether to use a broader or narrower term), and general vagueness. For example, a program description might allude to work with texts at some point, yet not explicitly state text analysis until later, only once, when it is embedded in a list of other examples (e.g., GIS, text mining, network analysis), with a reference to sentiment analysis elsewhere. Since texts could involve digitization, publishing, or other activities, we would not code ‘Text analysis’ immediately, and we would only code it if students would were be guaranteed exposure to this such methods in the program. To complicate matters further, there is no single term for text analysis in TaDiRAH—it spans across four (‘Content analysis’, ‘Relational analysis’, ‘Structural analysis’, and ‘Stylistic analysis’)—and one coder might apply all four terms, another only some, and the third might use the parent term ‘Analysis’, which also includes spatial analysis, network analysis, and visualization.

Even after reviewing these examples and the definitions of specific TaDiRAH terms, we could not reach a high level of intercoder agreement. However, we did find comparing our term assignments to be useful, and we were able to reach consensus in discussion. Based on this experience, we decided that each of us would code every program/course description and then discuss our codings together until we reached a final agreement. Before starting our preliminary codings, we discussed our understanding of each TaDiRAH term (in case it had not come up already in the exercise). We reviewed our preliminary codings using a visualization showing whether one, two, or three coders applied a term to a program/course description. In an effort to reduce bias, especially framing effects (cognitive biases that result from the order in which information is presented), the visualization did not display who had coded which terms. If two coders agreed on a term, they explained their codings to the third and all three came to an agreement. If only one coder applied a term, the other two explained why they did not code for that term and all three came to an agreement. Put another way, we considered every term that anyone applied, and we considered it under the presumption that it would be applied until proven otherwise. Frequently, our discussions involved pointing to specific locations in the program/course descriptions and referencing TaDiRAH definitions or notes from previous meetings when interpretations were discussed.

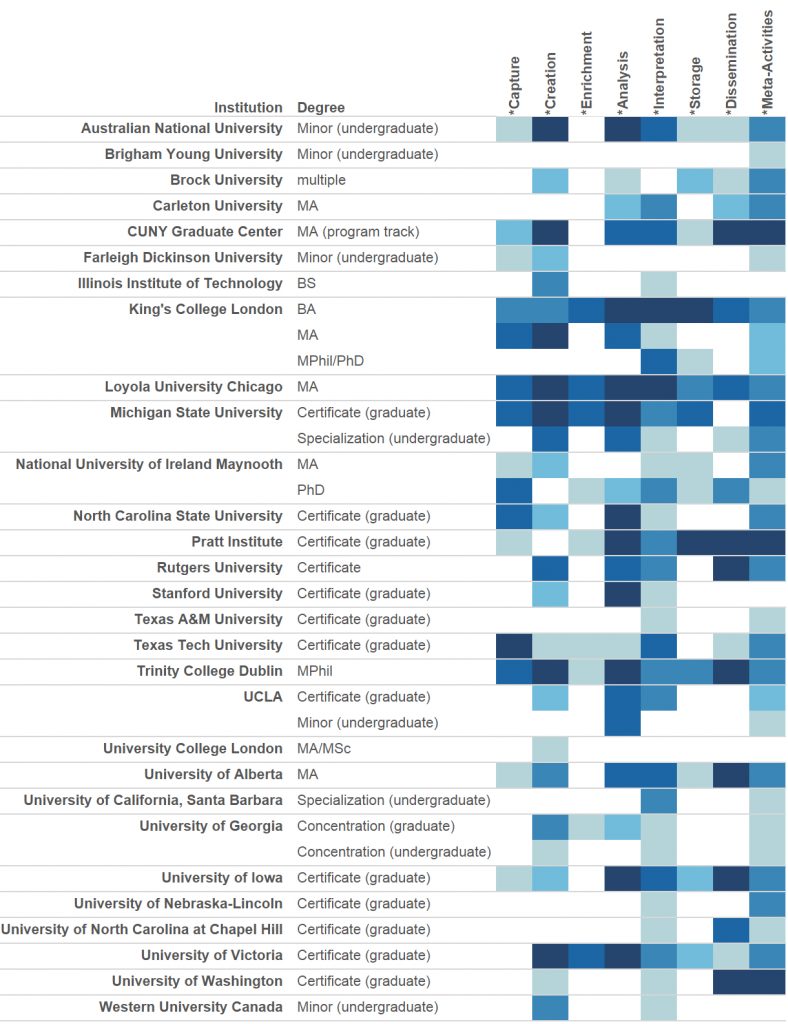

In analyzing our final codings, we used absolute term frequencies (the number of times a term was applied in general) and weighted frequencies (a proxy for relative frequency and here a measure of individual programs and courses). To compute weighted frequencies, each of the eight parent terms were given a weight of 1, which was divided equally among their subterms. For example, the parent term ‘Dissemination’ has six subterms, so each of those were assigned an equal weight of one-sixth, whereas ‘Enrichment’ has three subterms, each assigned a weight of one-third. These weights were summed by area to show how much of an area (relatively speaking) is represented in program/course descriptions, regardless of area size. If all the subterms in an area are present, that entire area is present—just as it would be if we had applied only the broader term in the first place. These weighted frequencies are used only where programs are displayed individually.

Initially, we had thought about comparing differences in stated activities between programs and required courses. While we found some variations (e.g., a program would be coded for one area of activities but not its courses and vice versa), we also noticed cases in which the language used to describe programs was too vague to code for activities that were borne out in required course descriptions. For this reason and to be as inclusive as possible with our relatively conservative codings, we compared program and course data simultaneously in our final analysis. Future studies may address the way in which program descriptions connect to particular coursework, and articulating such connections may help reveal the ways in which DH is taught (in terms of pedagogy) rather than only its formal structure (as presented here).

Analysis and Visualization

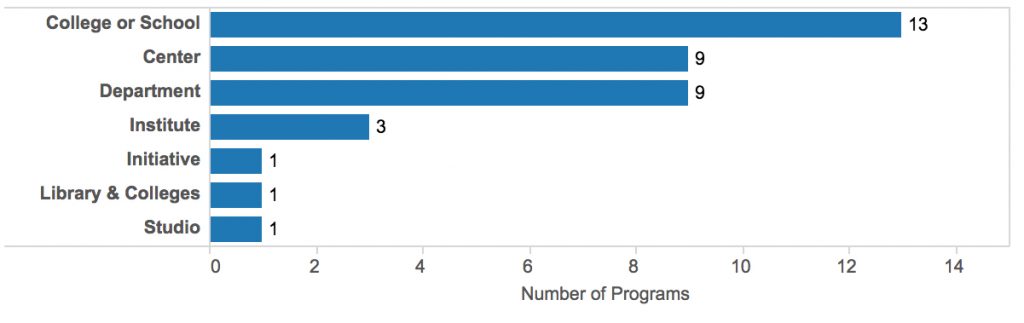

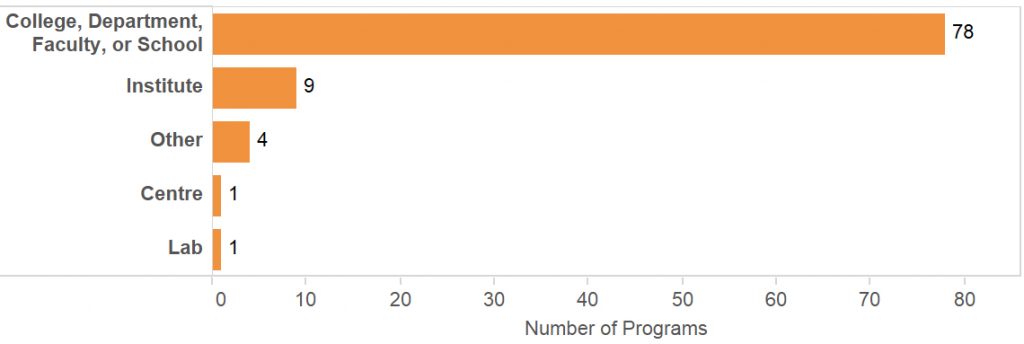

In analyzing program data, we examined the overall character of each program (its title), its structure (whether it grants degrees and, if so, at what level), special requirements (independent study, final deliverables, fieldwork), and its location, both in terms of institutional structure (e.g., departments, labs, centers) and discipline(s). We intended to analyze more thoroughly the number of required courses as compared to electives, the variety of choice students have in electives, and the range of departments in which electives are offered. These comparisons proved difficult: even within an American context, institutions vary in their credit hours and the formality of their requirements (e.g., choosing from a menu of specific electives, as opposed to any course from a department or “with permission”). These inconsistencies multiply greatly in an international context, and so we did not undertake a quantitative study of the number or range of required and elective courses.

Program data and codings were visualized using the free software Tableau Public. All images included in this article are available in a public workbook at https://public.tableau.com/views/DigitalHumanitiesProgramsSurvey/Combined. As we discuss in the final section, we are also building a public-facing version of the data and visualizations, which may be updated by members of the DH community. Thus, the data presented here can and should change over time, making these results only a snapshot of DH in some locations at the present.

Anglophone Programs

The number of DH programs in Anglophone countries has risen sharply over time, beginning in 1991 and growing steadily by several programs each year since 2008 (see Figure 1). This growth speaks to increased capacity in the field, not just by means of centers, journals, conferences, and other professional infrastructure, but also through formal education. Since 2008, there has been a steady addition of several programs each year, and based on informal observation since our data collection ended, we believe this trend continues.

Program Titles

Most of the programs in our collected data (22, 59%) are titled simply “Digital Humanities,” along with a few variations, such as “Book History and Digital Humanities” and “Digital Humanities Research” (see Figure 2). A handful of programs are named for particular areas of DH or related topics (e.g., “Digital Culture,” “Public Scholarship”), and only a fraction (3 programs, 8%) are called “Humanities Computing.” We did not investigate changes in program names over time, although this might be worthwhile in the future.

Structure

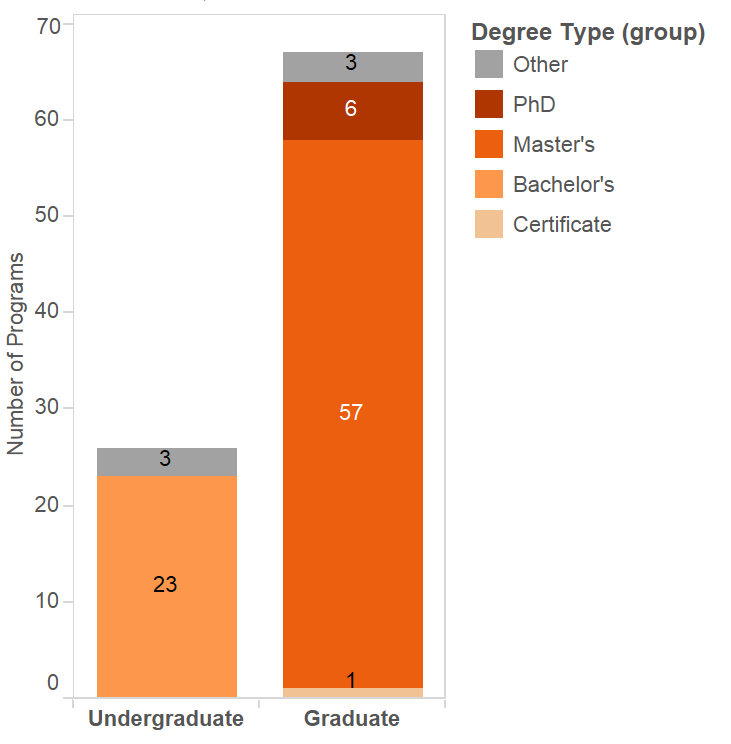

Less than half of DH programs in our collected data grant degrees: some at the level of bachelor’s (8%), most at the level of master’s (22%), and some at the doctoral (8%) level (Figure 3). The majority of DH programs are certificates, minors, specializations, and concentrations—certificates being much more common at the graduate level and nearly one-third of all programs in our collected data. The handful of doctoral programs are all located in the UK and Ireland.

In addition to degree-granting status, we also examined special requirements for the 37 DH programs in our study. Half of those programs require some form of independent research (see Figure 4). All doctoral programs require such research; most master’s programs do as well. Again, we only looked for cases of explicit requirements; it seems likely that research of some variety is conducted within all the programs analyzed here. However, we focus this study on explicit statements of academic activity in order to separate the assumptions of practitioners of DH about its activities from what appears in public-facing descriptions of the field.

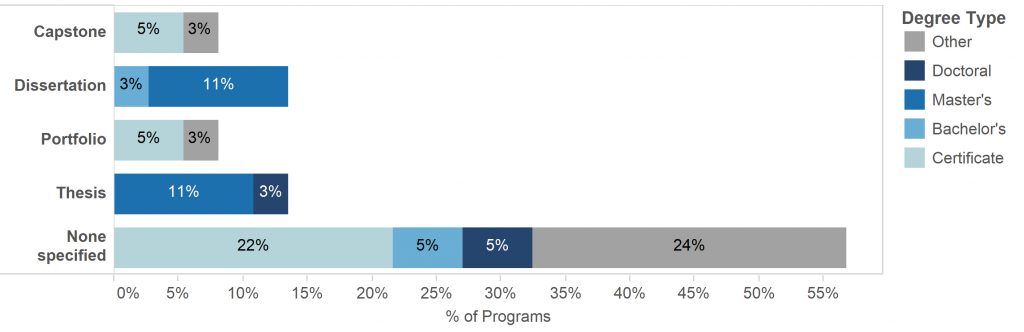

Half of DH programs in our collected data require a final deliverable, referred to variously as a capstone, dissertation, portfolio, or thesis (see Figure 5). Again, discrepancies between written and unwritten expectations in degree programs abound—and are certainly not limited to DH—and some programs may have not explicitly stated this requirement, so deliverables may be undercounted. That said, most graduate programs require some kind of final deliverable, and most undergraduate and non-degree-granting programs (e.g., minors, specializations) do not.

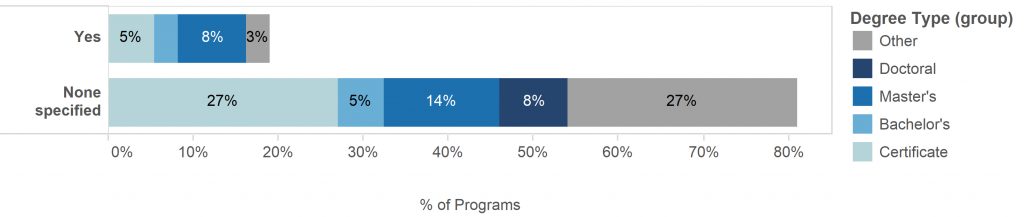

Finally, about one-quarter of programs require fieldwork, often in the form of an internship (see Figure 6). This fieldwork requirement is spread across degree types and levels.