BeardStair: A Student-Run Digital Humanities Project History, Fall 2011 to May 16, 2013

David T. Coad, University of California, Davis

Kelly Curtis, San Jose State University

Jonathan Cook, San Jose State University

Dr. Katherine D. Harris, San Jose State University, Faculty Advisor

with Valerie Cruz, Dylan Grozdanich, Randy Holaday, Amanda Kolstad, Alexander James Papoulias, Ilyssa Russ, Genevieve Sanvictores, Erik White

Figure 1. Header from first BeardStair Website

Abstract

In the current landscape of Digital Humanities and digital pedagogy, it is rare to see Master’s-level graduate students fully engaged in the process of building Digital Humanities projects, especially at large, underfunded public universities. The BeardStair Project is one such effort, housed at San Jose State University (SJSU). This article, conceived and written by graduate students on the BeardStair team, provides a detailed, reflective history of that work. It started when five rare Modernist books were left, anonymously, in San Jose State University’s library drop box, and were discovered by one of the four SJSU students who became the original BeardStair team. Working independently in a process of scholarly inquiry, with guidance from SJSU’s Digital Humanities scholar Dr. Katherine Harris, they began working on what they called the BeardStair Project—named for two of the books’ artists, Aubrey Beardsley and Alastair. Several semesters later, a spring 2013 course in modern approaches to literature, composed of eleven graduate students, set a research agenda of producing a scholarly digital edition of these rare books. This scholarly digital edition would be focused by the claim that “these books act as autonomous literary and artistic objects that can be valued for their merits outside, and in spite of, their original purpose as salable commodities.” The BeardStair Project is an ongoing experiment in the Digital Humanities, yielding unique implications for administrators, faculty, and students who are interested in building Digital Humanities projects and fostering collaborative digital pedagogies.Introduction to the BeardStair History

Beginning in the fall of 2011 as a loose yet focused and fruitful student collaboration, and extending through the spring semester of 2013 (with an open door to future instantiations), the BeardStair Project is a unique and collaborative student-run Digital Humanities project at a large, under-funded state university. This is a history of what happened in that project (especially in its second instantiation), with the goals of illustrating the immense value of Digital Humanities work in English and Humanities Departments, as well as the persistent progress that can be made at any institution when the Digital Humanities are embraced.

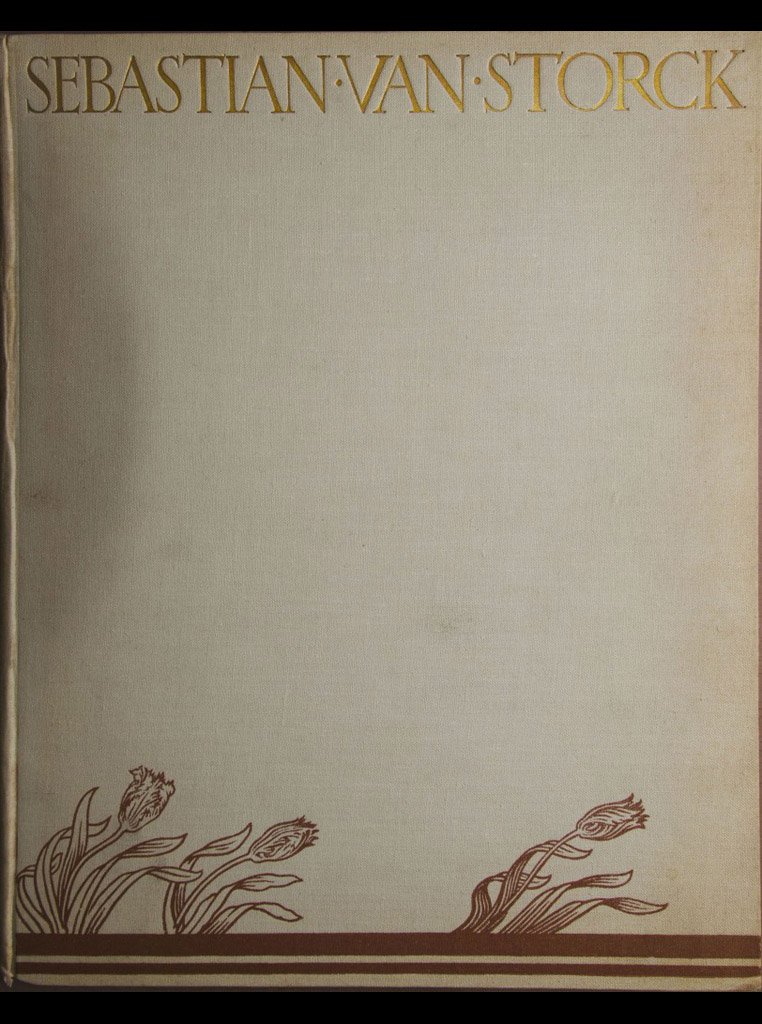

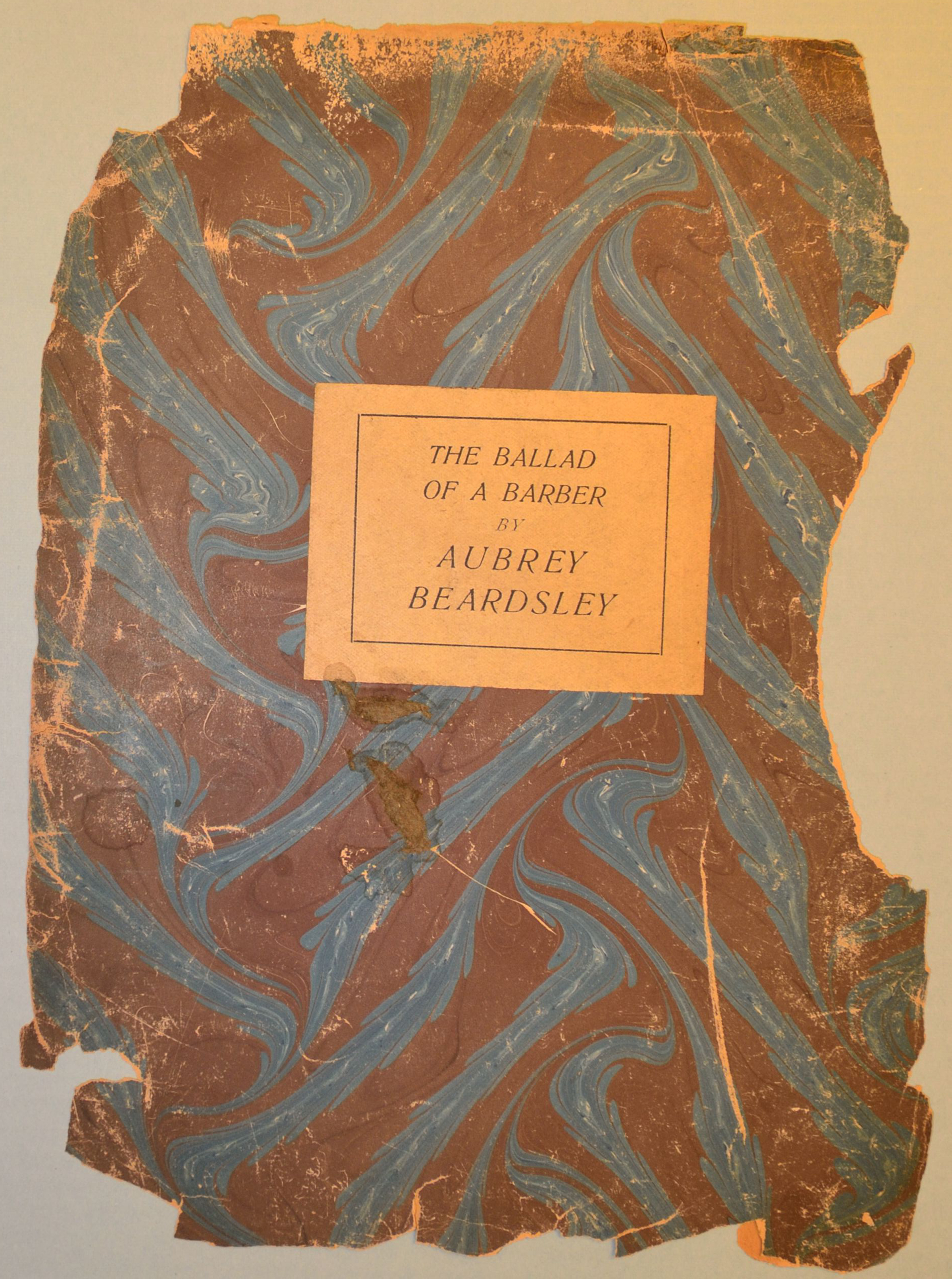

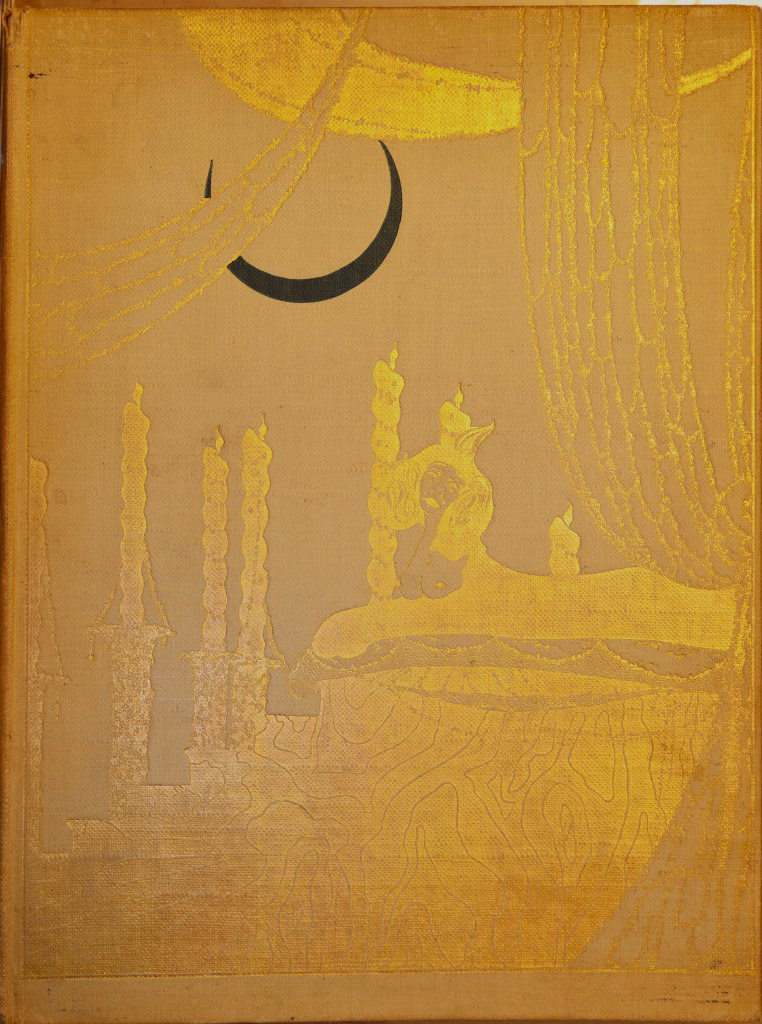

The original BeardStair participants began the project in Fall 2011 when five old, mysterious illustrated books were left by an unknown party in a book-return bin at the San Jose State University campus library. Jesus Espinoza, a student who worked at the SJSU library at the time, brought the books to Dr. Katherine Harris, whom he knew from an undergraduate Digital Humanities course offered in a prior semester, a course that also discussed the history of the book. After doing some initial research on the discovered books, Dr. Harris discovered that two of the books, being rare editions with original artwork, were potentially valuable. She felt compelled to get students involved in making a digital edition of these valuable, cultural, literary, and historical resources. Of the artifacts that were most compelling there was a 1920 edition of Oscar Wilde’s poem, The Sphinx, a dramatic monologue ripe with Wilde’s wit and eloquence. There was also Sebastian van Storck, Walter Pater’s 1927 tale of a nihilistic Dutchman who achieves a tragic redemption by sacrificing himself to save a child, which was beautifully illustrated by Alastair. Finally, there was the Aubrey Beardsley’s 1919 edition of The Ballad of a Barber, a poem in ballad form that focuses on man’s aesthetic limitations.

Dr. Harris tweeted and emailed some former students who she thought might be interested in exploring and presenting research about the books. Four student participants, including Jesus, accepted and got involved in what became the original BeardStair project. They began by independently researching the books, their authors, artists, interpretations, and histories. The mix of undergraduates, graduate students, and former students met once a month to report on their research findings, ask new questions about the books, and set research goals for the next meeting. Dr. Harris served as a kind of project manager and advisor, but primarily, the students were in control of the research agenda and the act of researching. Eventually, the group accumulated enough intriguing information to present their findings at conferences and competitions (THATCamp Pedagogy, Re:Humanities Conference, and the CSU Student Research Competition).

However, because of a lack of funding and support from the university, these original BeardStair participants ran out of steam. In an effort to continue the project and award students with tangible success with regard to the project, Dr. Harris received approval to offer a graduate-level Digital Humanities course. The result was one of the most collaborative and exciting learning experiences many of these students had ever had the opportunity of being involved in.

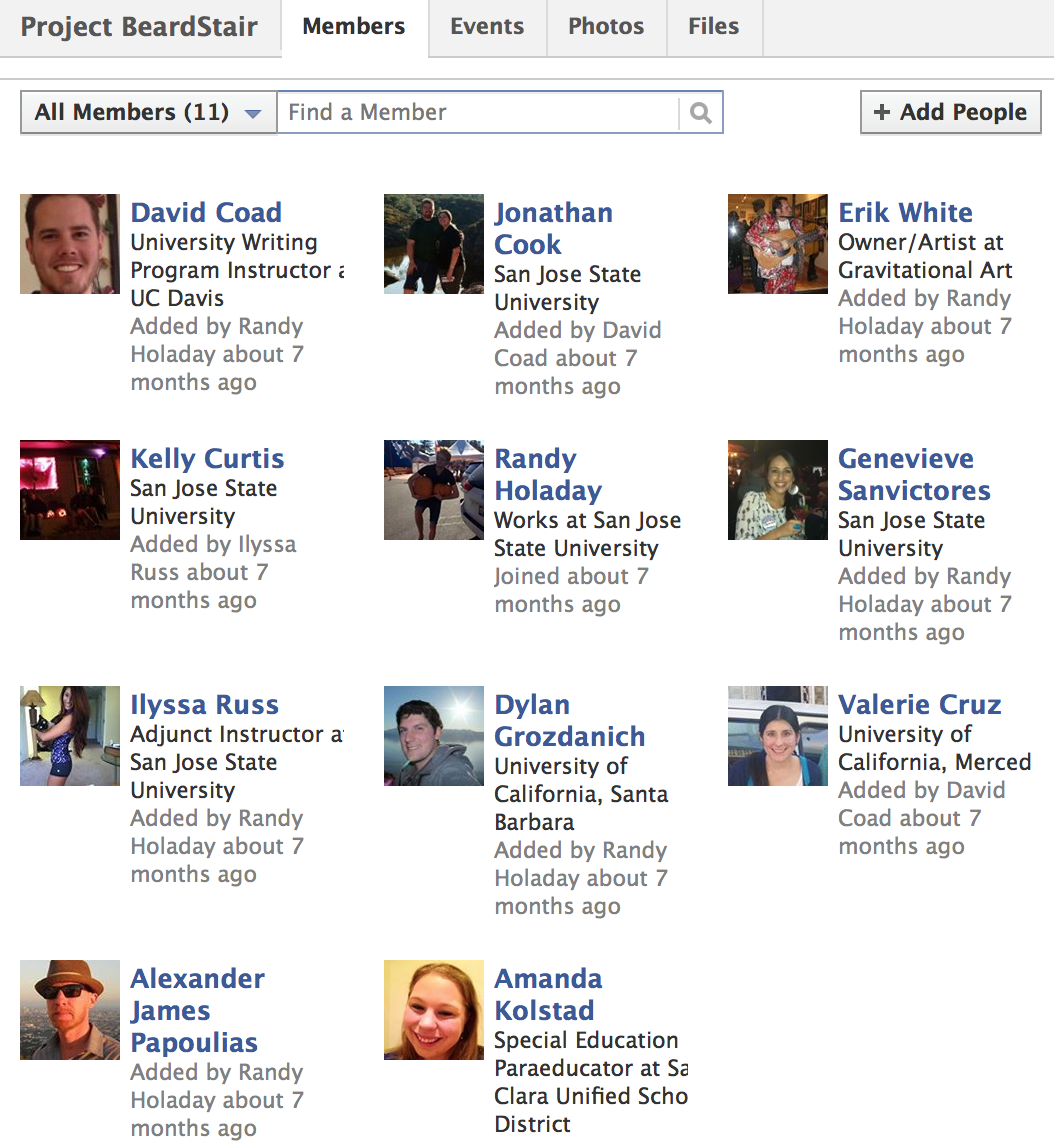

A seminar in modern approaches to literature was added to the course schedule, giving university credit to eleven graduate students who reviewed the original BeardStair participants’ work, set tasks and goals for the semester, read scholarly editing theory, engaged in Digital Humanities debates, and moved the Project toward its inevitable goal: to produce a digital scholarly edition of the works. In order to accomplish that goal, BeardStair participants had to be able to communicate effectively, and, after considering multiple options, in the classroom and out of the classroom, BeardStair decided to use a social media website, Facebook.

Facebook afforded BeardStair participants some crucial advantages in developing the project. First, Facebook is free, and groups can be created that are accessible via invitation only. BeardStair participants used Facebook in exactly that way to great effect: creating a collaborative group; and circumventing faculty interference (after all, they felt it was truly their project) and other potential hijackers. Facebook, as a social media construct, proved invaluable to the development of BeardStair ideas; indeed, Facebook allowed for the free exchange of ideas in an area most of us were already very comfortable working in. Individuals that would not normally speak in a classroom setting posted to the group message board, ideas flowed more freely, and progress was made more efficiently. And, when the time came to decide what direction the BeardStair Project should travel, Facebook was a capable medium for genesis.

The BeardStair Project needed a foundation, a vantage point from which to engage the texts. Roland Barthes’s discussion of the plurality of texts in his essay, “From Work to Text,” was especially important in developing such a perspective. Barthes wrote that the text is “irreducible” and “accomplishes the very plural of meaning” and textual meaning is represented as “an explosion, a dissemination,” whereby the “plural of the Text depends…not on the ambiguity of its contents but on what might be called the stereographic plurality of its weave of signifiers” (Barthes 1978). This analysis became the basis for Project BeardStair’s interpretive perspective, for BeardStair participants did not simply want to extract meaning from the found texts, as if they were simply a precious resource to be harvested, but, rather, to examine the texts as a whole—as part of a continuum—as representative of their time and artistic/cultural milieu. In short, BeardStair wished to find Barthes’s “weave of signifiers” throughout the artifacts, to sense these connections as a unified tapestry that might, with new light, elucidate an overlooked period of literary history.

Naturally, Barthes’s ruminations were quite complementary with regard to the BeardStair paradigm of collaboration. The reason for this was no coincidence, as BeardStair was, and is, deeply indebted to the core tenets of Digital Humanities studies as indicated in Dr. Harris’s (2013) recent article, “Play, Collaborate, Break, Build, Share: ‘Screwing Around’ in Digital Pedagogy, The Debate to Define Digital Humanities…Again.” Chiefly, the BeardStair participants employed collaboration, the willingness to explore multiple interpretations, and, equally important, a right to fail in the name of progress. There was always an essential need for fluidity in the BeardStair project—controlled, cohesive, cogent, yes, but absolutely fluid and adaptable. Digital Humanities is the only humanities field that affords that kind of freedom. Yet, even with freedom comes the inevitable burden of choice.

The BeardStair Project needed a medium with which to engage its audience. BeardStair wrestled with the idea of the “text,” vast as it was. Barthes provided a theoretical background, but there remained the issue of presentation from classroom conception to audience consumption. BeardStair had to choose between a digital archive of its texts or something more. The BeardStair participants’ understood that while a digital archive preserves and displays the material items along with secondary sources that relate to the items, they lack several fundamental elements, including the ability to include other scholars’ ideas in the discussion and to make an actual argument about the materials, which BeardStair participants found essential when it came to defining their project.

In their search for a method of defining the project that would include the fundamental elements they wanted to present, they confronted, in a different arena, the age-old question: what is a “text”? BeardStair considered displaying the texts online with findings and research, but that approach ignored the crucial, argumentative properties that BeardStair members thought important. BeardStair participants felt that if texts were merely collected, reproduced, and digitally stored, then the archival properties would not give the project the ability to develop a thesis and make an argument regarding the books’ intrinsic and extrinsic values.

The BeardStair participants acknowledged that by virtue of being archived, there would be an inherent argument about the books’ intellectual value. Whether one physically or digitally presents a text in an archive, one is making an argument about that text’s relevancy, importance, genre, and historical context. Yet an archive ostensibly grants an immense power of interpretation to archivist(s). BeardStair students were not convinced of such a strictly archival stance as such a position alienates the author from the historical context of the text, proposing that it may be manipulated for different purposes or motives from the original author’s intentions. In other words, the BeardStair project is motivated by the idea of disseminating the power of interpretation of value to a broader authorship that extends beyond the participants themselves.

Students who participated in the BeardStair project, in keeping with the spirit of Digital Humanities and collaborative efforts towards projects and arguments, wanted to utilize an approach that satisfied the efforts of the project while embracing the academic community and the public at large. Thus, BeardStair students decided to produce a scholarly edition. With a scholarly edition BeardStair participants were free to posit an argument without the risk of alienating or dismissing dissenting opinions. The scholarly edition functions much like an open forum—like any article of scholarship—in that it demands conversation, agreement or dissension aside. While the digital archive is honed and bent by the will of an individual, represented as truth, the scholarly edition represents the acceptance of plurality and the possibility for a true dialectic.

The BeardStair project is, fundamentally, constructed to be inclusive of the world at large. In support of such lofty goals, the project now has a working website, a digital mark-up protocol (TEI) for the text of an entire book, critical essays on all the books and artists, a project rationale (aforementioned), and a thesis that argues the value of the books’ place in the Modernist era.

As the semester progressed, BeardStair participants recognized a need for a Digital Humanities lab at SJSU and crafted a funding proposal highlighting the production needs for a project of BeardStair’s scope. Such projects are the realization of the potential of Digital Humanities studies and are essential to its survival, especially from an institutional/academic standpoint. BeardStair members are amazed and proud with what they have accomplished without funding support. The inclusion of a designated DH space could only bode well for future instantiations of the BeardStair Project.

The following is a complete project history of BeardStair to date. Much of the information here is drawn from blog posts on the class website, “The BeardStair Project: A Graduate-Student Driven Digital Project” (Coad et al. 2013). Here, in this boiled-down history, readers can immerse themselves in the origins of the Project and join the journey of the Spring 2013 collaborators. We’ve chosen to present the history in a chronological timeline so that others can read about successes and failures, and most importantly, engage with the process of creating an elaborate Digital Humanities project. It is the sincere hope of all of the BeardStair members, past and present, that readers of this piece will be inspired by what they read, our absolute commitment to collaboration, our fraternity of scholarship; we, BeardStairs, hope that the world—both academically inclined or otherwise moved by curiosity—will share in the joy of our labors, the successes and the failures we’ve had. It is our wish that this interactive history, full of images and links to course schedule and blogs, will inspire similar projects and adventures—that others might join us down the rabbit hole.

Project History

Early September 2011 Jesus Espinoza finds five rare books, not SJSU library property, left anonymously in the library return bin and flips through the profusely-illustrated pages. The images and the books’ quality remind him of an Honors Colloquium that he had taken with SJSU Digital Humanities and book history scholar, Dr. Katherine D. Harris. He brings the books to Dr. Harris and she determines the books’ handmade paper and uncut pages signal valuable book history. These books are original editions, yet far from pristine. Some are in better shape than others, but all show some signs of decay. However, the physical attributes of these books indicate the potential for valuable literary and historical examination relating to the method in which they were produced. Jesus immediately begins crafting a research project around these found books. Dr. Harris, Jesus, Colette Hayes (MLIS School of Library and Information Science student), Doll Piccotto (MA English), and Pollyanna Macchiano (BA English) form a volunteer research group that meets off-campus monthly. They discuss the books and uncover their mysterious past. The group decides the lavish color illustrations by artists Aubrey Beardsley and Baron Hans Henning Voigt (known simply as Alistair), should dominate the project. They decide to call their group, “BeardStair.” The group dreams of preliminary goals, the first of which is to exhibit the books in King Library Special Collections. The second is to construct a peer-reviewed digital edition, supported and maintained by the library and a scholarly community.

The Original BeardStair participants spend four months delving into every facet of the works – from their mysterious dumping into the SJSU library bin to the collective importance of Modernist artists’ books. The project beginnings are shared in detail at the blogging site, BeardStair.wordpress.com and in a fairmatter.com blog post called “Giving Students the Keys: Digital Projects” by Katherine D. Harris.

November 28, 2011 The “Student Driven Project: BeardStair” blog post at triproftri is acknowledged as an Editor’s Choice for Digital Humanities Now. BeardStair participants are inspired to find out that the Digital Humanities community is watching their pedagogical experiment.

February 23, 2012 Pollyanna Macchiano gives a presentation on BeardStair called “The Underground Voice in Digital Humanities” at THATCamp Pedagogy. The Digital Humanities community has begun to notice the BeardStair Project as a multilayered experiment in both old books and new ways of engaging with the humanities.

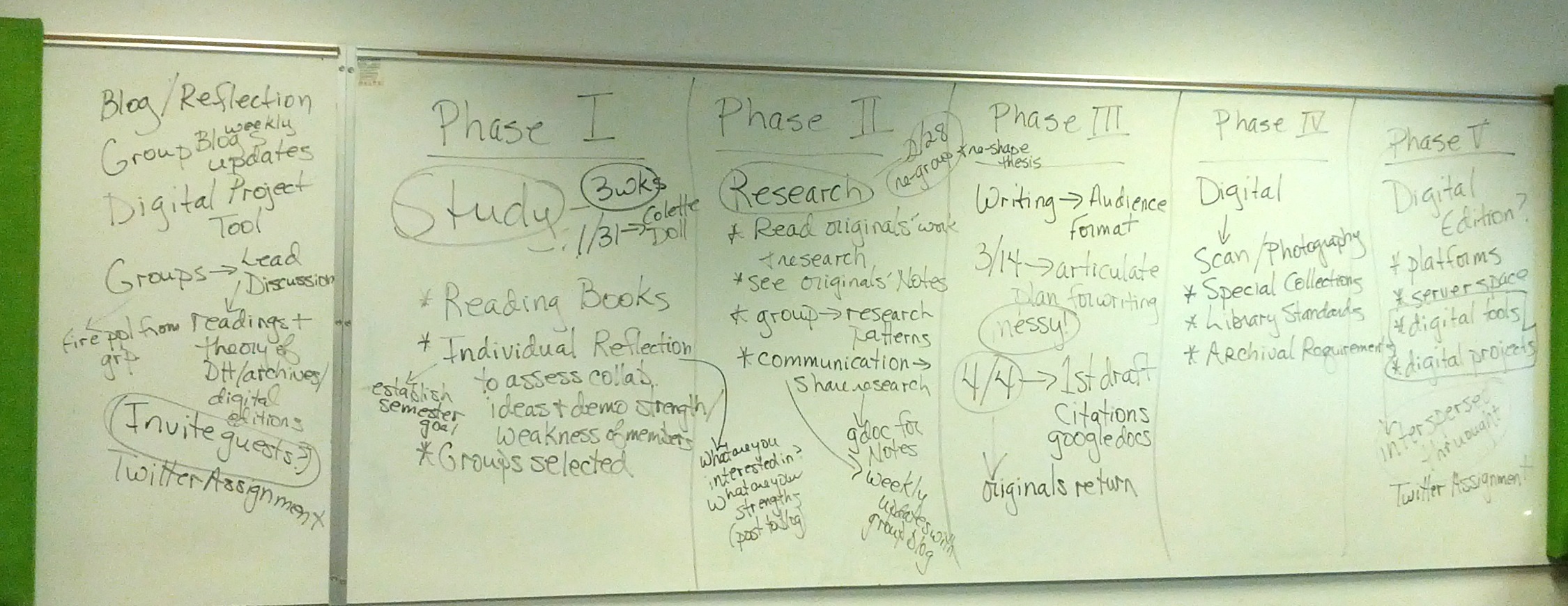

January 24, 2013: Phase Zero of English 204 Begins

Phase Zero marks the continuation of the BeardStair Project by SJSU M.A. and M.F.A. students in a classroom setting. Dr. Harris opens with the caveat that this is a collaborative learning environment and the group is encouraged to think outside of traditional humanities, collaborate, and embrace failure. To start, some assignments are posted to the blog site and the schedule of phases (a step-by-step plan of the collaborative work we want to accomplish throughout the semester, adhering to a set of codified student learning objectives introduced by Dr. Harris at the outset of English 204) is developed with the enthusiasm of meeting key semester objectives: By the conclusion of the course, we will have added to BeardStair Project and will (ideally) submit it for review by NINES, a peer-review entity for nineteenth-century digital projects. In essence, students will immerse themselves in the burgeoning field of Digital Humanities in order to contribute to a real-world scholarly publication. Working within a set of core student learning objectives (SLOs), the English 204 group sets out to accomplish goals by first conceding a few truisms, borrowed from Professor Matthew Kirschenbaum’s English 668k course website at the University of Maryland, which states that not all questions would have been answered; not all texts would have been read; all avenues of experimentation would not be exhausted; and the entirety of Digital Humanities would not be explored. The inception of BeardStair embraces Kirschenbaum’s SLOs, but the execution of BeardStair, in its current form, is reflective of Dr. Harris’ English 204 SLOs in that the group functions as a collaborative unit with a final, multimodal project being created at semester’s end. Above all else, Project BeardStair was/is an experiment, with all respect and reverence given equally to success and failure.

Figure 5 “What We Did On Our First Day” Schedule of Phases

January 31, 2013 Phase One Begins, Research

The class discusses the definition of Digital Humanities, the essence of collaboration, and catches up on where the original BeardStair participants left off. They are introduced to the physical books and divide into two groups–the Technical Group and the Literary Group–with the objective of covering all project phases. Each group creates its own private Facebook group page for efficient communication, brainstorming, and sharing documents. These Facebook groups become instrumental in organizing, sharing ideas, posting documents, and keeping group members accountable. Facebook will become the single most effective method of collaboration the BeardStair teams use.

Figure 6. Tech Group Facebook Page

February 7, 2013 Team members continue to read and research the theory of Digital Humanities and what it means to do DH. They come to understand that the Digital Humanities involves the use of digital tools to represent material items and the secondary resources that discuss them. It’s determined that each week both Lit and Tech groups will prepare a blog post to share our process and document progress. The Lit Group’s initial action is to familiarize themselves with the Project, both the books and the research conducted by the original BeardStair members. They process this material into summaries so that, moving forward, research can be done without requiring use of the physical books. The Tech Group reviews several digital archives to discover positive qualities of functioning projects similar to BeardStair. These digital archives, however, appear to only present the primary materials and secondary documents and do not make a community argument about the value of the texts, something BeardStair participants believe is important to their project.

February 14, 2013 The class continues discussion on digital publications and determines that the category of publication the Project best fits into is “digital scholarly edition.” All class members write an individual blog on the “anxiety about sustainability, project management, productive unease, scholarly editing, or building.” Meanwhile everyone thinks seriously about how to define the BeardStair Project. The main question is: Are we creating a digital scholarly edition or a digital archive? They determine that digital scholarly edition best fits the Project type because they aim to present the materials, make an argument about their value, and allow scholars from the broader community to comment and make their own summations of the works, either in agreement or disagreement with BeardStairs’. A digital archive would meet the first two goals of sharing the works and secondary sources about the works, but it would not allow for input from outside the project members, which seems to go against the original values of the participants. The Tech Group begins “articulating a structure for our digital project” and creates GoogleDrive documents that contain features the Project should include. They consider using a timeline to articulate the project using Dipity.com. After looking into whether their books already have digital editions, and not finding any, they are reaffirmed in the value of this project. They consider working with The Internet Archive to house the digital editions. They also research metadata and advocate creating metadata for the Project. The Lit Group publishes materials to the class’s private Google drive, including summaries of each book, brief contexts, descriptive bibliographies, and the start of an annotated bibliography. Here, the group shifts from gathering and understanding the Project as it had been left by the original BeardStair participants into new areas of research guided by the class’s interests: publishing houses, materials, and the artist Alastair.

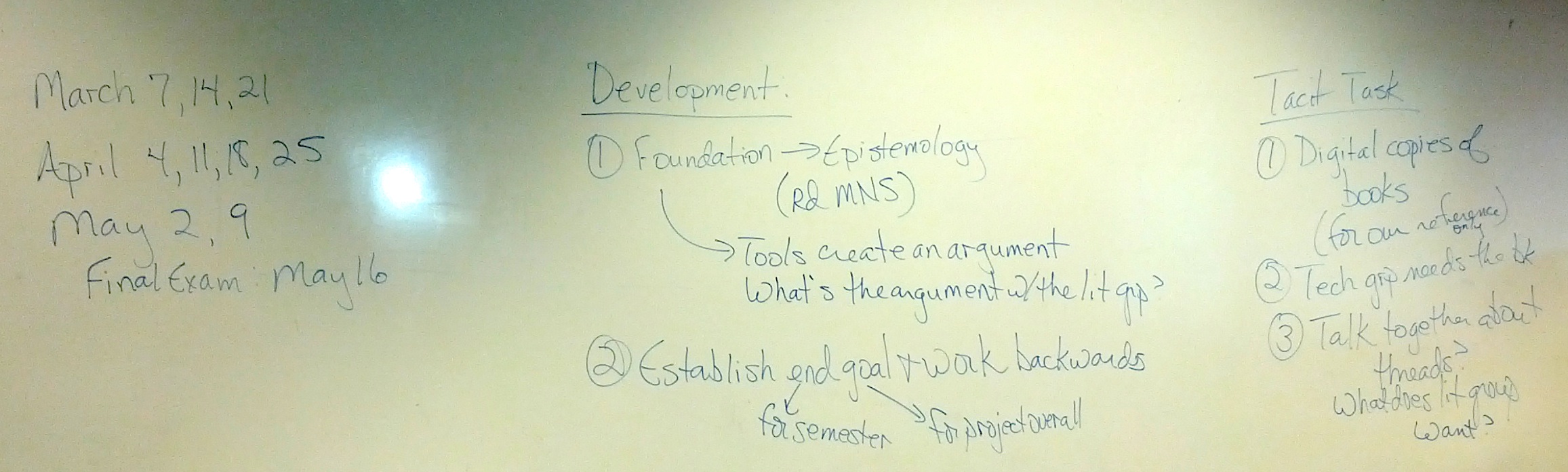

February 28, 2013 Phase Two Begins, Development

The class discusses mark-up and sustainability and discusses goals for the Development Phase. The group acknowledges the need for a thread between the books, a thread that can be explored in research and could be presented for publication. It is determined the class wants to get the Project online by the end of the semester, but they also see a need to present an argument rather than a haphazard publication of the materials. Following research leads Dr. Harris discovered through Twitter, the Lit Group decides the BeardStair books are actually part of the livres d’artistes genre, as defined in Johanna Drucker’s book, The Century of Artists’ Books (1995). The discovery’s significance is twofold: it begins to make cohesive each member’s different area of research, and the collaborative nature of livres d’artistes lines up nicely with the collaborative nature of the BeardStair Project, connecting the literary aspects to the larger discussions about Digital Humanities which seems to circle a debate about where the emphasis of DH should lie: on digital tools, or the people that use them? The Literary Group provides the first sketches the Project’s structure based on their research about livres d’artiste books. The Tech group researches mark-up and the Text Encoding Initiative. TEI is XML streamlined and requires knowledge of coding. It also has its own set of guidelines that requires assimilation of new rules and standards. The Tech Group determines that implementing TEI will require either an immense investment of time, or outsourcing, which would be problematic because it would cause us to lose control over the Project’s argument. This discussion of TEI leads the BeardStair participants to think about how they are going to define “text,” and what we want to accomplish with the texts we have. They look for advice and an understanding of “text” to James Cummings’s “The Text Encoding Initiative and the Study of Literature” (2008) and an article by Stephen Ramsay and Geoffrey Rockwell, “Developing Things: Notes toward an Epistemology of Building in the Digital Humanities” (2012) and come to the conclusion that “text” acknowledges a continuum of works that share connections. Essentially, this is how they explain how BeardStair is linking the disparate textual volumes they have used.

Figure 7. Loose Sketch of Development Phase

March 7, 2013 In the spirit of collaborative group work, they complete their first peer evaluations using the Association of American Colleges and Universities’ online Teamwork Value Rubric. Completing evaluations of one another’s work leads to a focused group assessment of how well the Lit Group is functioning. The result is a reinvigoration of collaborative effort, individual accountability, and renewed group dynamics after the group had struggled to cooperate. During this class meeting, the BeardStair participants discuss “epistemology” and “hermeneutics” in an ongoing effort to determine “What is our argument?” They brainstorm and establish goals for the entire Project, and determine what can be completed in the remainder of the college semester. They also discuss a possible structure for the Project argument.

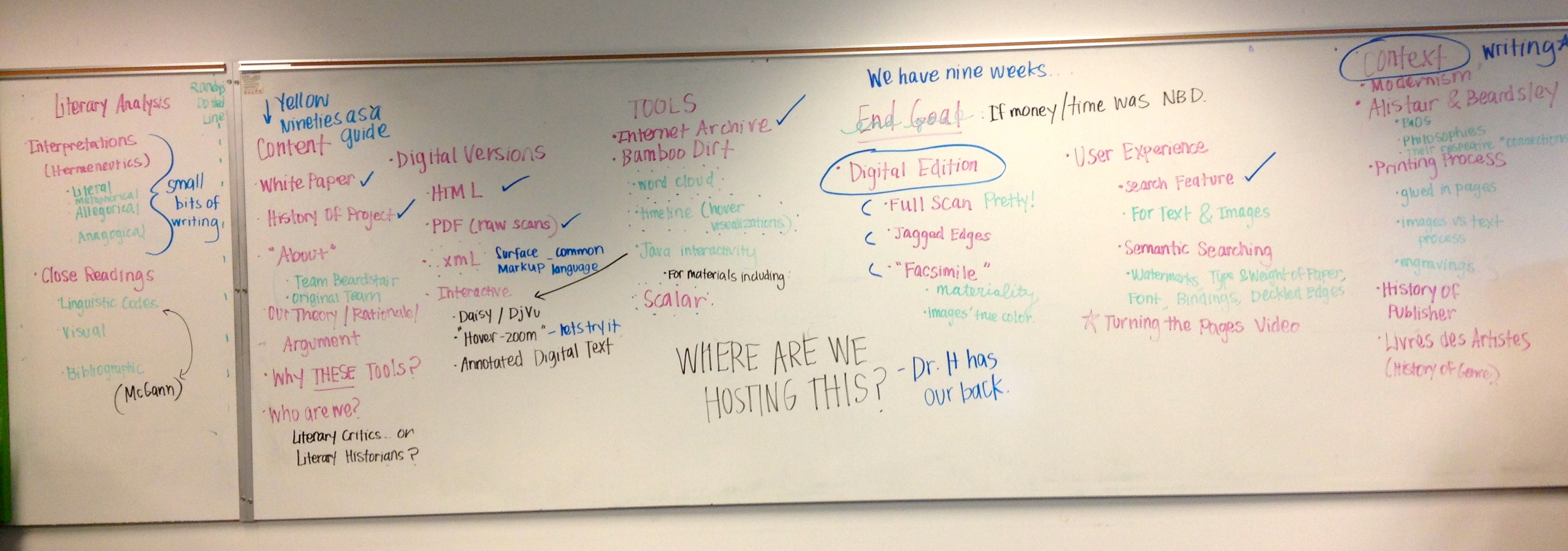

Figure 8. BeardStair Website Dreaming… If time and money were no object.

The Tech Group works on two prototypes for the audience interface. One is an e-book style presentation, and the other is an html presentation. They continue to research TEI and markup and consider how much is realistic to include in this project considering the timeline. BeardStair participants are interested in the concept of the text as an “artifact.” The quality and production of the books is of interest as well, which seems to imply that the Tech group and Lit group are on the same page regarding the “material” thread. The Tech Group is reminded that the quality of BeardStair images must represent the materiality of the books. The Tech Group reviews The Omeka project developed by the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University and the Scalar project developed by the Alliance for Networking Visual Culture at the University of Southern California and find that the open-source scholarly publication projects offer a possible publication venue for BeardStair.

March 14, 2013 Phase Three Begins, Building

The BeardStair participants have been discussing what type of argument to make by asking questions about what they want the public to get out of their experience with the books. They ask, What do these books say? What does BeardStair want them to say? They determine that they would prefer a peer-reviewed publishing platform, but there is debate about whether the group will be able to pull together all the writings and materials in time for peer review. The group discusses using Scholarly Editing as the publication site. There is still ongoing discussion and inquiry about using Omeka or Scalar as publishing platforms. The Lit Group produces the first formal drafts of the context for the webpage and posts them to the Google Drive Master Documents folder. This brings about unanticipated questions of style and formatting. Members of the group also start thinking about the theoretical framework for the Project, mainly surrounding questions about the significance of the artwork present in the “commercial” livres d’artistes. The Tech Group is still working on a scanned version of the books and is determined to provide a facsimile showing the jagged edges and watermarks. They work to find the appropriate medium in which to convey these images, but the digital files for the Project are huge, the data is immense, and time is limited. BeardStair has made some progress in terms of types of digital tools and the kind of digital interactivity they want. They determined they need an HTML version and a PDF version of all books. One Tech Group member is learning XML/TEI markup, so it is possible that they could include an XML version by the end of the semester. They hope to include a flipbook viewer like DjVU or Daisy. They are also considering including a forum that allows viewers to post comments and ideas.

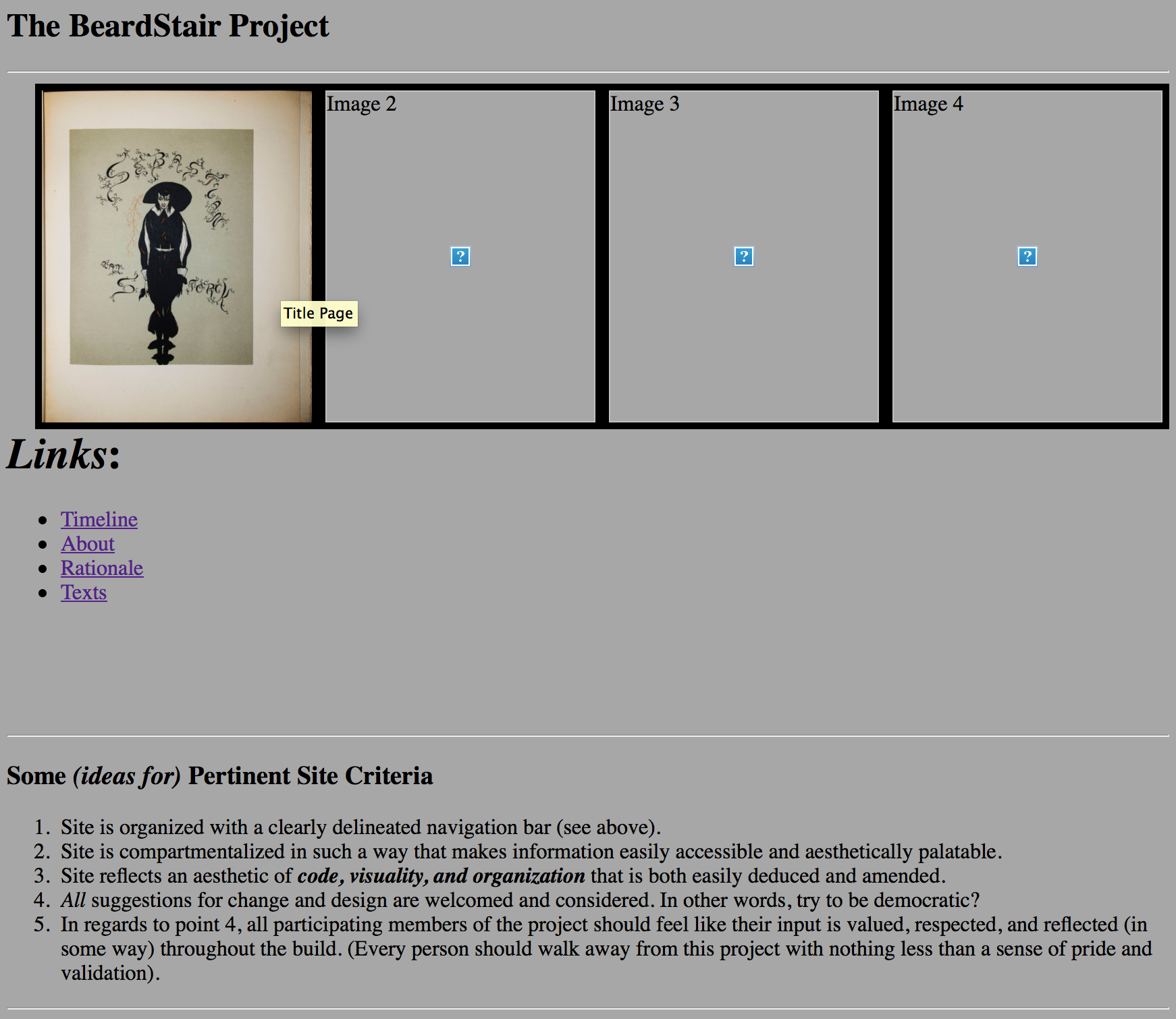

March 21, 2013 The group chooses a project historian to document successes and opportunities for the project’s About page. BeardStair participants are getting serious about avenues for online publication. Scholarly Editing has responded that they accept projects submitted with multiple authors or strict limitation on images. Lit Group has been in contact with Scalar to get advice on the use of Scalar as the BeardStair platform. It is unknown when Scalar will be available to the public. The Literary Group settles on Modern Language Association as a standard method of citation. This week also begins the editing stage. Each individual in the Lit Group shifts the focus away from his or her own writing to the writing of other group members. This also brings the focus of the Lit Group more to the end product, creating questions of scope, specificity, and breadth of research. The larger class asks the Lit Group to begin thinking about a thesis for the Project, which they are resistant to doing because they don’t feel research is complete yet. The Tech Group questions how much server space the digital edition will require and grapples with finding a host. The group leans towards Scalar, but still questions if they have enough hands or time to add detailed metadata. The project is still struggling with the large size of images required for publication. A mock-up of the website is developed for class discussion and review, and refreshes the class’s excitement and enthusiasm about the project. The Literary Group completes all formal drafts of contextual writing that both presents their research on the authors and illustrators related to the BeardStair Project and examines the value of artists’ books of the Modern period.

Figure 9. BeardStair.com Mock Up

April 4, 2013 The Tech Group chooses a new team leader to give another member the opportunity to have that responsibility. The BeardStair participants are now three weeks into what they had originally estimated would be the “building” phase of the Project. At its April 4th meeting, a small gathering of collaborators discusses the first draft of the Project rationale and the first draft of a Project history. This is a milestone in the Project because both groups felt directionless without a thesis to argue and move forward with. The group decides to look into creating a Kickstarter campaign to fund the Project, but at this point, one member buys server space to host the website because he sees the need to push forward. The Project tried to avoid this common Do-It-Yourself approach to the Digital Humanities, but funding opportunities are limited.

April 11, 2013 After much deliberation and collaboration BeardStair settles on a Project thesis: “We claim that these books act as autonomous literary and artistic objects that can be valued for their merits outside, and in spite of, their monetary direction.” This argument, that the books have intrinsic value, is a rebuttal to Johanna Drucker’s (2005) ideas about the genre that argue such artists’ books were only of commercial value. BeardStair will continue working on a Project rationale with the developing thesis in mind. Over the next week, they will also explore Omeka and its potential as a platform for the BeardStair Project online. BeardStair buys a domain name and some server space for the website www.beardstair.com. The group had discussed creating incentives for contributors who would donate to BeardStair Project through Kickstarter, such as early releases or expanded access. However, because BeardStair participants want the project to be freely accessible to all and have no intention of creating competition between outside contributors, but would rather increase collaborative efforts from the greater community, they decide against seeking funding through Kickstarter. Instead, they discuss putting a “donation” button on the web page to help recoup some of its out-of-pocket costs due to lack of departmental and university funding for Digital Humanities. Several BeardStair team members are continuing to learn TEI, though it’s a struggle. They try to gauge the amount of time it might take to create TEI for all the books’ content. The discussion turns to “big picture” ideas, particularly the lack of university funding for Digital Humanities. Dr. Harris proposes that team members work on a funding proposal for a DH center at SJSU. The proposal will need to touch on space, materials, and funding support needed for such a center. As importantly the proposal will need to address questions such as: Why have such a center? How would it enhance our education? How would a DH center help with the completion of a project like BeardStair? The BeardStair class also reorganizes the teams to reflect the new work-groups needed: TEI, Project History, Omeka Group, and Funding Proposal. The role of the BeardStair historians is determined as one that formulates a readable work that points to significant conclusions about the project’s process. The historian is not so much concerned with whether BeardStair meets its goals but more with the milestones that changed the process and evolution of the project. The team looks at several ways to share their history: a narrative, an interactive timeline, or a scholarly essay. Thinking realistically about the time left in the semester, the team settles on an interactive timeline with short narratives to elaborate on team milestones.

Figure 10. BeardStair.com

Figure 10. BeardStair.com

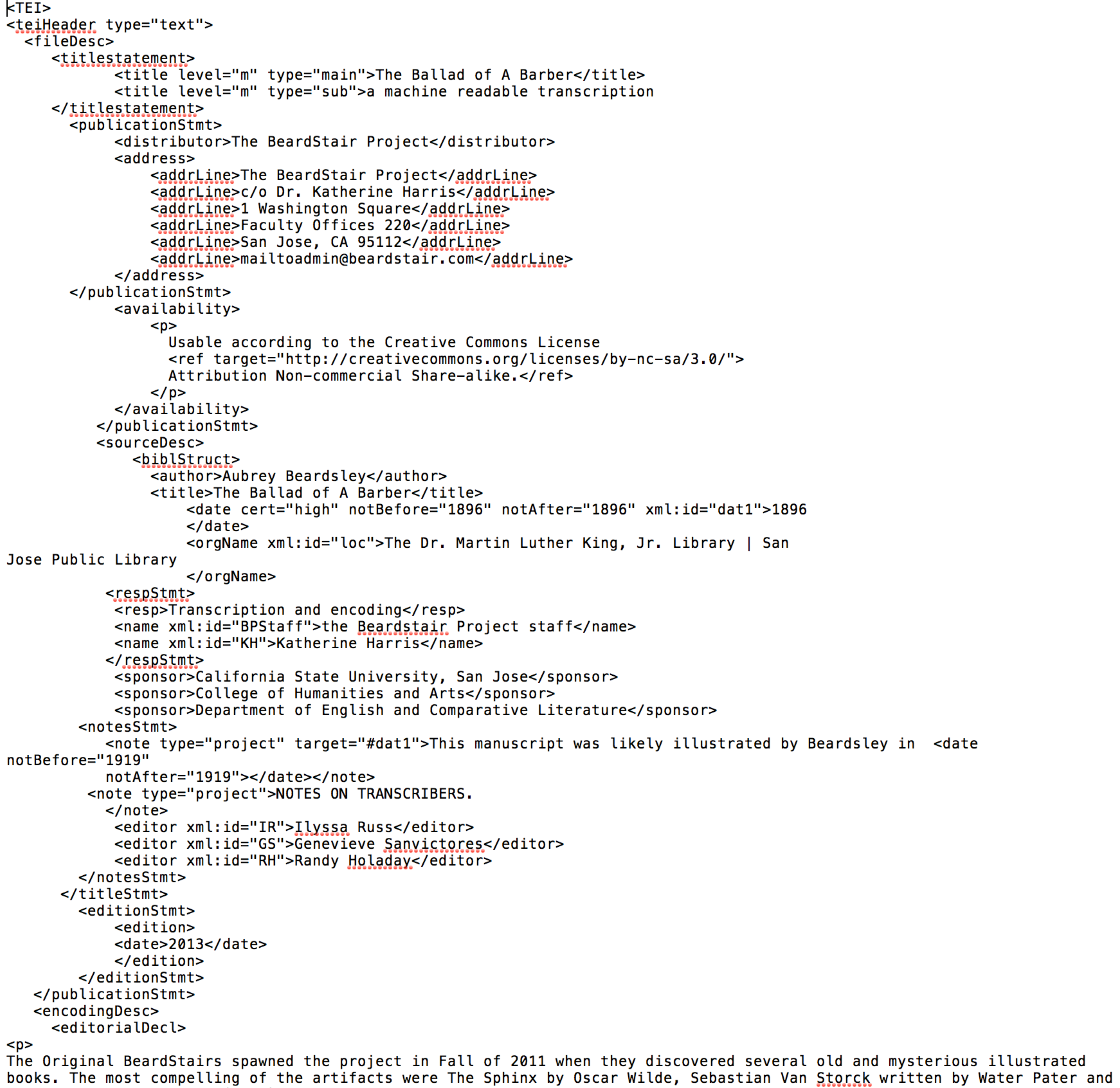

April 18, 2013 Each group continues development of their sub-areas of BeardStair. TEI mark-up for the title page and header of Ballad of a Barber is completed and the TEI goal for the end of the semester is to create a header for each book and complete all TEI markup for Ballad of a Barber. The Project Historians comb through class notes, blog posts, and the class’s weekly schedule, along with reaching out to the original BeardStair team, to produce a cohesive history of the project. It is decided that at the second-to-last meeting, the group will discuss publishing on pedagogy in a scholarly journal. The funding group continues work on a draft of the funding proposal letter, and has contacted Costal Carolina University to ask for advice about creating a small lab. This week, the funding proposal group has shared an outline of its draft with the team in its blog post and asks for input and suggestions regarding goals and specifics.

Figure 11. Ballad of the Barber TEI Header

Figure 12. The BeardStair To-Do List for Week 10 of 14 for the Spring Semester

April 25, 2013 The week begins with a discussion on the Team Rubric Evaluations each member will complete for all class members at the end of the semester. Also the BeardStair participants are asked to prepare a blog post for the final week of class addressing skills–both hard and soft–learned in the class. The funding group creates a spec-list for a potential Digital Humanities center, using its own Incubator Classroom and other DH centers as examples. The Omeka group arrives at an adequate solution to the problem it has had with pictures, and can now represent the photographed texts in their entirety as PDF documents. Omeka–a free open-source platform that appears to have a large and dedicated enough following that it should remain supported for some time–looks viable, and the group has hosting space ready. Implementation should require incorporating BeardStair’s aesthetic and functional ideas into the Omeka site. The historians have settled on using a timeline with short narratives as the format. This should be a concise and navigable way to highlight project milestones. Dr. Harris has been diligent about recording weekly events, decisions, and discussion topics; and the groups have also been consistent about posting blog entries that we have been drawing from to write the project history. The TEI group continues with its learning tutorials. They are eager to learn the text encoding protocol, but admit progress is slower than they had hoped it would be. Their hope is that they will each be operating on the same level of proficiency soon, and will be able to reach their semester goals.

May 2, 2013 Phase Four Begins, Publication

Original BeardStair founding member, Jesus Espinoza, joins the team for the meeting, and hears a presentation about the semester’s activities. The historians share their latest draft and ask for the group’s input. The group sees a mockup of the BeardStair’s Omeka site. There is a draft of the project rationale, and the group is asked to review and provide feedback during the coming week. The meeting concludes with some things to think about: What will the next instantiation of this group do? Where does the next team pick up the BeardStair Project, and where will they take it? The TEI group uses several new tutorials (www.codeacademy.com and www.w3schools.com) and reports learning has become easier, though the TEI process is still time-consuming. The header for Ballad of a Barber is done, and coding of the text is underway. TEI headers for The Sphinx and Sebastian van Stork will follow. The funding proposal group drafts several proposal letters for various audiences. They work to revise the funding letter to the SJSU Humanities and Arts dean and identify and revise it for specific audiences, such as national grant making organizations. They ponder how to communicate the exciting possibilities of a SJSU Digital Humanities center and how to articulate the purposes of the DH Center.

May 9, 2013, Last Meeting of Spring 2013 The team is required to revisit the idea of “done” and reads the Digital Humanities Quarterly essay “Published Yet Never Done” (Brown et al. 2009). Regardless, the BeardStair team members cram to meet goals and deadlines before the end of the semester. They review the written documents on all books, check the Omeka mock-up and read and comment on the Project Rationale. The TEI group brings the headers for each book and a complete mark-up of Ballad of the Barber will be ready by the conclusion of the course. The Funding Group has a strong draft of the funding proposal and a final draft of the Project History will be ready by May 16 for the faculty advisor’s comments. The group is still thinking about sending one TEI book with documentation to Scholarly Editing. Also, each BeardStair team member is privately working on a Team Value Rubric for one another to assess each individual’s contributions to the Project and effectiveness as collaborators. Everyone has been working on a To-Do list for the next installment of BeardStair so the torch can be passed efficiently and the goals of the original BeardStair participants and this graduate class stay in sight.

Conclusion

The BeardStair Project started with the discovery of five old, rare books in the San Jose State University Library. Who dropped them in the returns box? Are they valuable? What are Artists’ books anyway? The new, impromptu custodians of the books dubbed themselves BeardStair and their curiosity quickly grew into a passion. They wanted to know everything they could about the books as soon as possible. To support that passion, they developed a set of informal values surrounding their exploration. Those values–deep respect for the books and an enthusiasm to share them with the greater community–have been passed from one iteration of the BeardStair Project to the next. The exploration of Modernism, the livres d’artistes genre and the desire to illuminate the works for the academic community is nothing new to the School of Humanities. What is emerging in the school, and what the original BeardStair participants naturally found in themselves, is the desire to make the works accessible to all, online, for free, in a live discussion. This passion for sharing the books’ intrinsic and extrinsic value has become the most important aspect of Digital Humanities for the BeardStair participants. The BeardStair Project itself had a rocky and intermittent start. Originally, the team performed informal research and met for dinners to discuss findings. After months of what their adviser referred to as “down the rabbit hole” enthusiasm, the team of volunteers found that for the project to meet the goals they had set based on their values, the project would need more nurturing than they could give. They simply didn’t have the labor power, technological resources, funding, or university backing to get the books onto the web and out to the world. This under-resourcing problem seemed to point to possible approach to the Digital Humanities that could result in the completion and continued growth of projects: collaboration.

When the Spring 2013 graduate class took over BeardStair in January, they had more technology (though still, a full service DH lab remains a dream), they had almost three times as many people working collectively, and they had some, albeit minimal, university backing. (SJSU provided an incubator classroom and granted course units toward individual Master’s degrees.) Several aspects of working collectively quickly became essential to the new team. They developed project phases and To-Do lists to keep them moving toward their goals. They assigned strong leaders and used technology to communicate regularly and to hold themselves accountable for individual deadlines. They used teamwork rubrics as a way of getting and giving feedback to their peers. The collaboration itself was a powerful tool for moving forward with BeardStair, but perhaps the most important value the team developed was unabashed creativity which was unencumbered by the fear of failure and the fear of incompletion. Letting go of the long-held belief that one must finish a project to be successful allowed the team to create new ideas of expression and take the presentation of the books on a new path, a path that better represents the value of the books themselves. While the Spring 2013 team did not accomplish every one of their goals for the semester, they did learn to see that BeardStair, as a Digital Humanities project, is an organic, living thing. The team finished their semester with a To-Do list that enabled them to pass the torch to the next generation of members who hopefully will develop their own values, creativity, and goals for the project. Additionally, from the university perspective, the Spring 2013 graduate-level Digital Humanities class was a success.

While there may be few tangible products generated by the class, it’s clear by looking at the project history that each of the San Jose State University English Department student learning objectives was met. Students gained a more complete understanding of the Modernist period and the literature it generated. They completed significant amounts of research and produced critical write-ups of their findings that will be posted online with the project. Also, they were very prolific with the written word and their own interpretations of Digital Humanities through their weekly blog posts. Dr. Katherine Harris blogs extensively on the SLOs in relation to the conclusion of the 2013 BeardStair Project class in her fairmatter.com blog post called “BeardStair.” From the perspective of the students who participated in the Spring 2013 Digital Humanities class at SJSU, the class offered learning opportunities beyond the English Department student learning objectives. Collaboration, resolving conflicts with peers, spearheading projects without the overt influence of a faculty adviser, and giving new meaning to the essence of what it means to “finish” a project, were among the skills learned in the BeardStair class. These skills are applicable in both academia and the greater working world. Each student who participated, and whomever will participate in the future, in projects like BeardStair knows the value of the Digital Humanities and what they offer in the university setting.

Appendix: Blog Notes on Collaboration from the 2013 BeardStair Participants

The Excitement of BeardStair by David Coad

“From when I first asked Dr. Harris to explain what her Digital Humanities class would be like, to the first day of class, I entered this class with a great excitement to build something digital in a working, collaborative environment. When we got to working, I got a little lost some weeks, not seeing the big picture, and thus, not knowing the best way to contribute to it. However, as I pushed forward, I found that working collaboratively in a (sometimes confusing, but) always rewarding environment, I found that working with others to make a digital argument was something that I wish I had the experience of much earlier in my academic career.”

Reflexion by Jonathan Cook

“I have a sense of accomplishment; I feel proud of what I have done. Perhaps more important than that, I am proud of those with whom I have collaborated, and, with what they—we collectively—have accomplished, I am content to have found myself in the midst of a such an agreeable lot, as they were willing to push me as much as I was willing to push back. The result, no matter how far removed from the ideal, is far more gratifying than any exam or composition exercise or recitation of tired ideas could be.”

Reflections on Building a Digital Project by Valerie Cruz

“It is my hope that the next group to take up the BeardStair Project will be able to gain funding and complete the digital scholarly edition that we have started. Although, we were able to put an edition online; it does not have all of the digital aspects that we would have liked to get our thesis fully across. I also hope that future classes will be able to do similar projects on other texts once this one is finished, and that they would possibly be able to do projects in collaboration with other departments within the Humanities.”

Personal Reflection and the Argument Against ‘Get ‘Er Done’ by Kelly Curtis

“There is one major difference with this class than my other classes as SJSU. In my other three classes this semester, I’m turning in something that is done. I’ve done the research, the writing, the proofreading, and I’m done – here ya go – goodbye. In Digital Humanities we did all the work, research, writing, proofing, and there’s more to go. This Project will never be done, because it’s digital. It’s a mold-able modality.

“But, with projects like BeardStair, I would like to see the word ‘failure’ eventually work its way out of the language. I understand it’s there to protect students from anxiety should they not reach all their goals. It’s the same reason we called our dreams ‘dreams’ and goals ‘goals,’ but we’re not failures because we only accomplished so many of the tasks on our list, nor are the Original BeardStair participants because they didn’t get the Project to take flight. In fact, we, as are they, are part of something bigger. They we’re the spark, we were the problem solvers, and the next installment of BeardStair Project, well, they’ll refine and continue. They’ll take the Project in their own direction.”

BeardStair Reflection by Dylan Grozdanich

“Well, here we are at the ‘end’ of our BeardStair Project. It’s been an interesting and slightly frustrating ride for me on a personal level. The most obvious frustration has been the idea of the ‘final project.’ We never had a final format for our research and have not implemented a template anywhere at the moment. It’s slightly annoying on some level. This though has been the way the Project has gone.”

Reflecting on a DH Course by Randy Holaday

“From this class, I learned that the perspective of a Digital Humanist necessitates advanced understanding of a piece of literature, and thus becomes part of that ‘range of theoretical frameworks’ us graduate students are expected to understand and utilize…Digital Humanities is a different framework for understanding literature. For example, our work with creating mark-up language for the digital editions of the BeardStair books creates and translates our unique argument to an audience far more diverse than a classroom.”

Reflection by Amanda Kolstad

“My experience with collaboration had previously been limited to undergraduate “group projects” which usually ended with me doing the majority of the work. So, I walked into a huge challenge; this class was collaborative and technological, so I tried to let go of control and tried to just ‘let it happen.’ … I struggled… I struggled a lot… Because I was so used to working alone, and only being accountable to myself, I decided ‘not to bother my group until I found something worth sharing.’ This was not a successful choice. Without communication about my process and progress, my group was left believing that I wasn’t contributing. This was perhaps my biggest challenge with the course; I had to learn to communicate, even if I felt like I had nothing to report.

“My group struggled at our mid-semester check-in. We were struggling with the collaborative elements and communication, and tensions were running high… After some difficult and honest conversations, the Literary Research group redoubled our efforts. We checked in weekly, even if we didn’t have much to report. We divided tasks, but we also worked in partners to edit each other’s work. We shared research, we established a Facebook group; in short we moved our relationships with each other out of the class room and into our real lives.”

Some (Almost) Final Thoughts on the BeardStair Project by Alexander Papoulias

“Certainly, our whole semester has been about creating a thesis argument and using the research we’ve done to support it. What made the first half of the semester so nerve-wracking for us perfectionists, was doing research and writing before the thesis was formulated, and not knowing to what end we were researching and writing. That’s where patience with the process comes in. Flying blind for a while, and trusting that the quality of the team and its work will yield something valuable.”

Reflecting on BardStair by Ilyssa Russ

“Many of the other reflections talk about the process, but I guess I want to talk about the emotional “letting-go” I sort of feel. It’s hard to give this Project up, especially when you’ve invested so much of your time and energy into FIGURING OUT something completely foreign from the start. I’m hoping future BeardStairs can feel the same passion about this Project as our group did.”

Personal Reflection by Genevieve Sanvictores

“While the course definitely examined the question of how the humanities can embrace technology, I think that first and foremost it has been an experiment in collaboration. In many of my other graduate seminars research is done privately and papers are produced in solitude. While students often share their paper proposals and results in class, the work is left entirely up to the individual student.

“One thing that I have to say was difficult (yet rewarding) was dealing with failure. We initially had grand dreams for our project. We wanted to produce a digital scholarly edition that would razzle and dazzle. Then reality hit. Not only did we face time constraints, but we also faced challenges with funding, sustainability and lack of technical skills. We had to find a way to embrace not being able to finish, which I think, is a very difficult concept for a graduate student to accept.”

Figure 13. Spring 2013 BeardStair Members

Bibliography

Beardsley, Aubrey. 1919. The Ballad of a Barber. H. Princeton, NJ: Schiele. OCLC 11178111 Barthes, Roland. 1978. “From Work to Text.” Image-Music-Text. New York: Hill and Wang. 155-64. OCLC 53211219

Brown, Susan, Patricia Clements, Isobel Grundy, Stan Ruecker, Jeffery Antoniuk, and Sharon Balazs. 2009. “Published Yet Never Done: The Tension Between Projection and Completion in Digital Humanities Research.” Digital Humanities Quarterly 3 (2). Accessed October 18, 2013. http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/3/2/000040/000040.html

Coad, David, Jonathan Cook, Valerie Cruz, Kelly Curtis, Dylan Grozdanich, Randy Holaday, Amanda Kolstad, Alexander James Papoulias, Ilyssa Russ, Genevieve Sanvictores, and Erik White. Faculty Advisor Katherine Harris. 2013. “The BeardStair Project.” Accessed May 16, 2013. beardstair.wordpress.com.

Cummings, James. 2008. “The Text Encoding Initiative and the Study of Literature.” In A Companion to Digital Literacy Studies, edited by Susan Schreibman and Ray Siemens. Oxford: Blackwell. OCLC 259753413.

Drucker, Johanna. 1995. The Century of Artists’ Books. New York City: Granary Books. OCLC 33826276.

Harris, Katherine. 2013. “Play, Collaborate, Break, Build, Share: ‘Screwing Around’ in Digital Pedagogy, The Debate to Define Digital Humanities… Again.” Polymath: An Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences Journal 3 (3): 1-26. Accessed September 28, 2013. https://ojcs.siue.edu/ojs/index.php/polymath/article/viewFile/2853/884

Ramsay, Stephen and Geoffrey Rockwell. 2012. “Developing Things: Notes toward an Epistemology of Building in the Digital Humanities.” In Debates in the Digital Humanities, edited by Matthew K. Gold. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press). OCLC 759909869.

Pater, Walter. 1927. Sebastian Van Storck. London: John Lane. OCLC 2362195. Wilde, Oscar. 1920. The Sphinx. London: John Lane. OLCL 5777162.

About the Authors

David T. Coad is a PhD student at UC Davis in Education with an emphasis in Writing, Rhetoric, and Composition Studies. He is interested in multimodal rhetoric, social media, and writing pedagogy. David graduated from San Jose State University with an MA in English, where he was grateful to get to work on the BeardStair team, and has recently been published in <i>Kairos</i> and presented at CCCC.

Kelly Curtis will receive a Masters in Fine Arts in Creative Writing from San Jose State University in December 2013. Her interest in the Digital Humanities lies with collaborative authorship, exploring new methods of presenting ideas and materials, and creating open source projects that are available to the broader community. She is currently seeking publication for her first novel and opportunities to collaborate on projects with other writers.

Jonathan Cook is currently working on his MFA in creative writing at San Jose State University. His areas of interest include Post-Structuralism, Deconstruction, Hermeneutics, and Existentialism—especially from thinkers like Barthes, Derrida, Camus, and Sartre.