Seven years ago, while reading the powerful and beautiful memoir Close to the Knives, I saw the author’s name pop up in the news. I was not sure how to pronounce it, but I definitely recognized it: Wojnarowicz. I was familiar only with his written work at the time, but I knew enough to understand the issues at play in the headlines accruing with each new Google News search: controversy, censorship, religion. Little did I know when I decided that this would be the topic of my senior seminar research in art history as an undergraduate that this was an echo of the Culture Wars twenty-some years earlier.

David Wojnarowicz (1954–1992) was a man of many talents. In addition to being a writer, Wojnarowicz was a visual artist, filmmaker, and musician who was active in New York City’s Lower East Side during the 1980s (McCormick 1984, 18–19). With the AIDS crisis escalating in the city, and many of his own friends, loved ones, and peers falling ill and dying, Wojnarowicz received his own diagnosis in spring of 1988, just six months after losing his friend and mentor Peter Hujar (Carr 2012, 391). After seeing his lover suffer from the disease—and ultimately die of AIDS-related complications—Wojnarowicz began exploring the pains and anxieties tied to loss and his own diagnosis through his art. He eventually stated, “Everything I made, I made for Peter” (Carr 2012, 179). The last few years of his life, Wojnarowicz was able to synthesize aspects of his private and public life to produce some of the most poignant work of his career amidst the Culture Wars. Before Wojnarowicz died of AIDS-related complications in 1992, he was challenged by a number of conservative groups that attempted to silence or distort his voice and art. I learned all of this as I followed the events unfolding in 2010 surrounding the removal of Wojnarowicz’s video A Fire in My Belly (1986–87) from the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery exhibition HIDE/SEEK: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture and read more on the artist himself.[1]

The process of researching and writing for this undergraduate capstone project was unlike any other academic work I had done previously. Instead of going to the library and checking out books and searching JSTOR as I had learned to do, I was Googling different keyword combinations and reading online comment sections. In some ways it felt very rudimentary, yet that was where the story was unfolding. I have since returned to these resources and looked at Twitter posts starting on November 30, 2010 containing the name “Wojnarowicz.” I knew that these events would later be looked at by art historians, cultural theorists, and politicians since the controversies that developed around Wojnarowicz’s work in 1989 and 1990 were touchstones for his career and the Culture Wars during the AIDS crisis.[2]

Yet one can glean only so much from mass media outlets, the blogosphere, and social media during a time of social and cultural upheaval. Knowing that I wanted to learn more about Wojnarowicz’s work and life beyond the published materials available and the shouting match of publicized controversies, I decided to head to New York City. Leaving my quiet, rural, liberal arts bubble, I found myself in Manhattan for the first time trying to navigate Chelsea in order to find an exhibition called Spirituality: Works by David Wojnarowicz, 1979-1990 at P∙P∙O∙W Gallery, which manages the David Wojnarowicz Estate. For me, this exhibition was a revelation and an affirmation that I was on the correct path with my research and writing. I was able to speak with a few people at the opening who had known the artist, experienced the world he lived in, and survived. These scattered conversations were glimpses into the past as well as an insight into the worldview of artists from the period. Everything I had been reading online hinted at the depth of Wojnarowicz’s work but failed to explore it fully before moving on to important but tangential issues. Moreover, from talking to people at the opening, I sensed the chaos of the 1980s in New York City and realized how poignant and concise Wojnarowicz’s work was back then—and remains today.

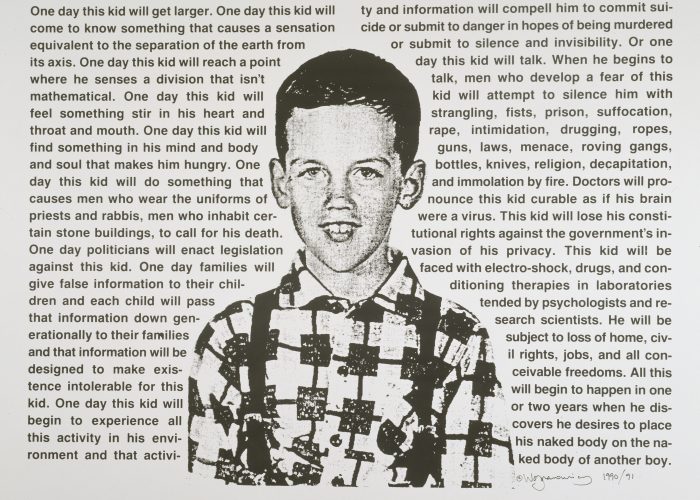

I lingered in New York for a few days attempting to soak up the atmosphere of the city that had helped shape who Wojnarowicz was. Eventually, I stumbled into the Whitney Museum of American Art and encountered Untitled (One Day, This Kid…) (1990). This powerful self-portrait depicts Wojnarowicz as a child surrounded by text describing difference, discrimination, fear, and the violence directed toward the young homosexual boy. Leaving the city, I returned to school full of passion to finish my project. Unbeknownst to me at the time, Fales Library and Special Collections at NYU held The David Wojnarowicz Papers, an unbelievably rich and complex collection of the artist’s journals, photographs, and objects.

Figure 1. David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (One Day This Kid…), 1990. Photostat, 30 ¾ x 41 inches. Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P·P·O·W, New York. ©Estate of David Wojnarowicz

A year later, in 2012, I eagerly awaited the opportunity to read Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz by Cynthia Carr. Thinking that I had written a thorough and carefully researched paper on Wojnarowicz for my senior seminar project, I was skeptical that I would learn anything I did not already know. I had fancied myself a writer and expert on Wojnarowicz, but after about twenty pages, I realized I was wrong. Carr’s biography is stunningly beautiful. Not only is it supported by astoundingly thorough research, Carr shared the world in which Wojnarowicz lived and knew things I could never have dreamed of discovering through research alone. The richness of this book cannot be understated, and ultimately I knew I needed to visit Fales Library to explore the David Wojnarowicz Papers.

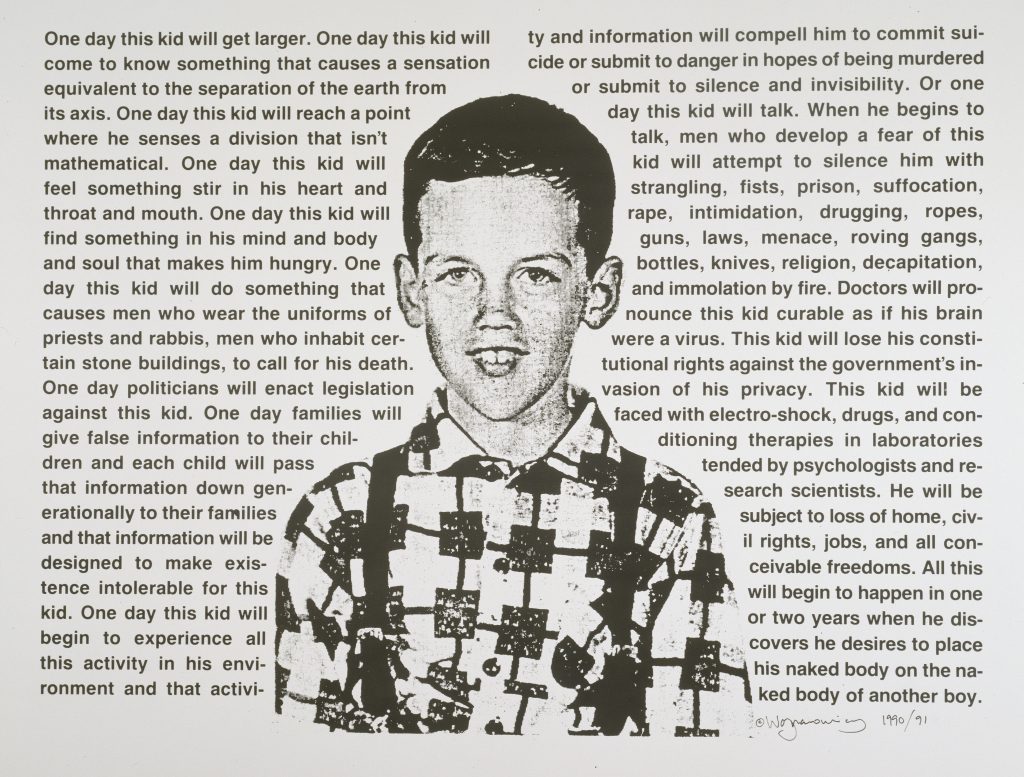

It would be another year before I returned to New York, but in 2013, Fales Library completed digitally scanning Wojnarowicz’s journals and made them available online. As I perused the documentation, I realized once again that I had no idea who Wojnarowicz really was as a person. I certainly knew things about him and could talk for extended lengths of time about his work, but I started considering new aspects of the artist’s life beyond where and when Wojnarowicz dated his journal entries. For example, where in Berlin and at what time of day on January 8, 1984 did he complete the entry “I leave down the road feeling slightly sad but good at last—removed from the handcuffs of taste and dictation of critics—free to make anything or nothing”?[3] Did he close the notebook emphatically and take a large sip of coffee thinking of his career as an artist? Alternatively, did he roll back over and go to sleep? With Wojnarowicz’s journals, I could piece together some of Carr’s insights more clearly than when I first read her account of Wojnarowicz’s life and career, but there was even more life present in these journals than even she could condense into a 600+ page biography.

Figure 2. Scan #7 from Box: 1 Folder: 17, “1984: Berlin, journal fragment” (1984), The David Wojnarowicz Papers; MSS 092; Box 1, Folder 17; Fales Library & Special Collections, New York University

Although I had been thinking about graduate school since completing my undergraduate studies, it was not until that summer that I began applying. I knew that I wanted to continue my education in art history, but I also felt that it would be beneficial to pair that knowledge with some technical skills. Library school was the most attractive option, and I received an acceptance letter from Pratt Institute in New York to enter their dual-master’s program in the History of Art and Design and Library and Information Science.

When I began the program in the fall of 2014, I did not intend to continue my academic research on Wojnarowicz, but I made plans to visit Fales Library to see the David Wojnarowicz Papers in person since I had been following their endeavors for the past three years. I eventually visited the collection and was able to study objects and documents I had only encountered in photographs or descriptions of Wojnarowicz’s work. The decision to come to Pratt was based on both a desire to study in a big city and the notion that art history and the rapidly developing digital world were bound to intersect in profound ways.

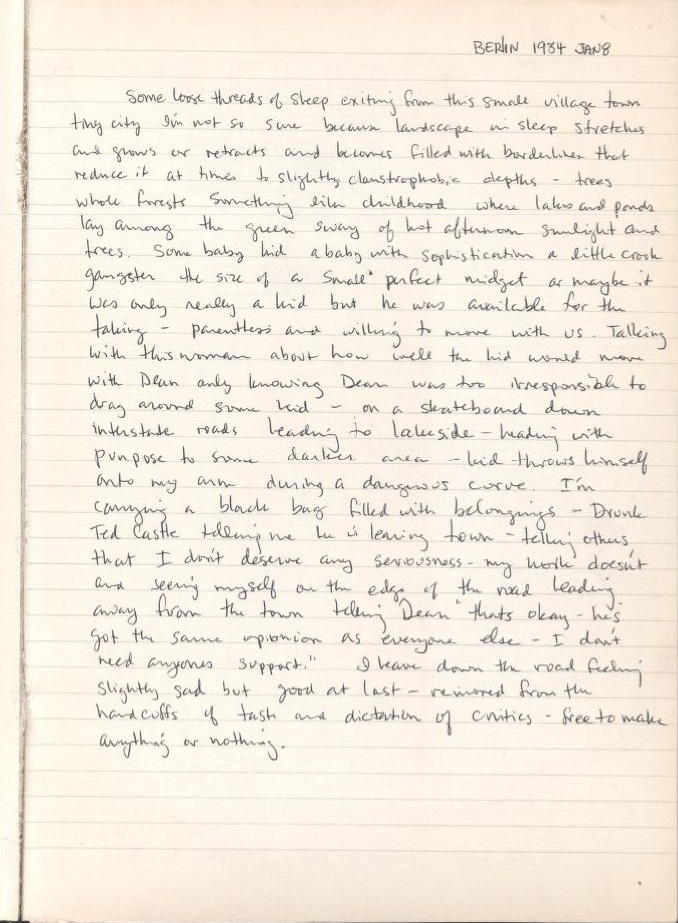

By the spring of 2016, I was taking a course titled “Installation Art: Design and Change” that would lead me to my thesis research on the installation and ephemeral art created by Wojnarowicz. The primary function of my thesis was to describe and collect documentation on this aspect of the artist’s creative output since many of these projects and works no longer exist. Believing that Wojnarowicz’s installations were emblematic of his biography, corpus, and culture, I began organizing my research. In an attempt to catalog and quantify Wojnarowicz’s intricate installations from photographs, exhibition checklists, and journal entries, I created an Omeka website that acted as a hierarchical collection management system (CMS) for the installations (Collection Level) and the objects therein (Item Level) assembled by Wojnarowicz throughout several periods in his career as an artist (Exhibit Level). Using an online platform was a way for me not only to organize my research but also to share it with others. This was by no means a “digital art history” project, but rather a digital tool that would help facilitate my analysis and interpretation of this aspect of Wojnarowicz’s work.

Figure 3. Untitled (Burning Child) Installation (1984), The David Wojnarowicz Papers; MSS 092; Box 80, Slide Box 48; Fales Library & Special Collections, New York University

I soon became aware that a project related to my thesis work was developing at NYU. The NYU project, known as the Artist Archives Initiative (AAI), shared some similarities to my own work, but was being executed on a far grander scale. Using the fabulously rich collection in the David Wojnarowicz Papers, a team led by Deena Engel, Marvin Taylor, and Glenn Wharton was undertaking the task of creating an interdisciplinary digital resource for scholars, curators, and conservators of Wojnarowicz’s work (Wharton, Engel, and Taylor 2016, 241–47). Having a finding aid is essential for a large collection like The David Wojnarowicz Papers and creating an HTML and single-webpage version allows for easier searching. However, this project went far beyond simple digitization. By populating this Wiki-based platform with data, text, images, audio, and newly created content, Fales was not only creating a tool that facilitated scholarly research but also providing a space for dialogue and contributions from the community. This was an ambitious project in digital art history that provided new pathways and models for academic research. After reaching out to the organizers, I joined the project as a researcher/student worker and was granted access to the David Wojnarowicz Knowledge Base prior to its launch in April 2017.

While consulting the finding aid for the David Wojnarowicz Papers, I requested materials for my thesis research, carefully taking detailed notes to make recommendations to the AAI team. I knew as well as anyone in today’s increasingly digital world that the user experience (UX) was almost as important as the content. In addition to subject research and content organization, I provided the AAI team feedback on the functionality and intuitiveness of the Knowledge Base. Not only would this resource be scalable and grow the more scholars used it, it could also provide a model for other organizations seeking to develop similar projects.

Although the notion that digital art history might replace the old ways of researching and learning about art and artists through direct experience and time spent in libraries persists, I would argue that we can rule out that possibility. Digital art history will never be a solution to all of the problems inherent in researching and speculating about the artist’s intent, meaning, and purpose in creating their art. Nor will it replace the individual achievements of scholars producing original interpretations. Rather, digital art history is one tool among many that we must use with respect, always acknowledging its limitations. With the technology and resources available to us today, we enjoy ever more opportunities to access material instantly regardless of geographic borders or traditional academic hierarchies. The necessity to sit quietly with a work of art in addition to careful consultation of related documents and resources is still paramount. We as art historians, curators, and conservators do not want to fall into the illusion that because we saw something online, or gathered new evidence from a digital algorithm, we know the “truth.” That being said, there are new opportunities and methodologies we can develop alongside these digitized resources. The David Wojnarowicz Knowledge Base and the Artist Archives Initiative at NYU are more than datasets, yet they are not traditional art-historical interpretations of an artist or their work. This is an endeavor in digital art history that grants access to digitized information and images while providing pathways for research and outlines frameworks for education. Computational tools and analytic techniques can be leveraged to our advantage. Collaboration and information sharing on a public yet vetted platform reflects the strengths and appeal of the internet. These are the first steps into digital art history, but it is up to us where we take our research and resources in the field of digital art history and what innovations we produce therein.

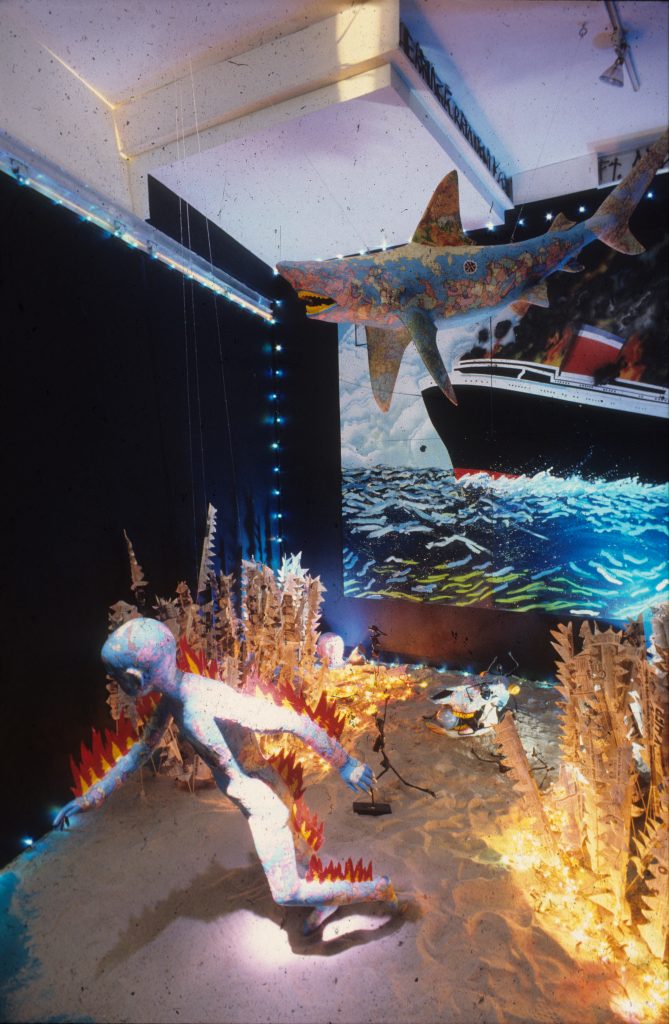

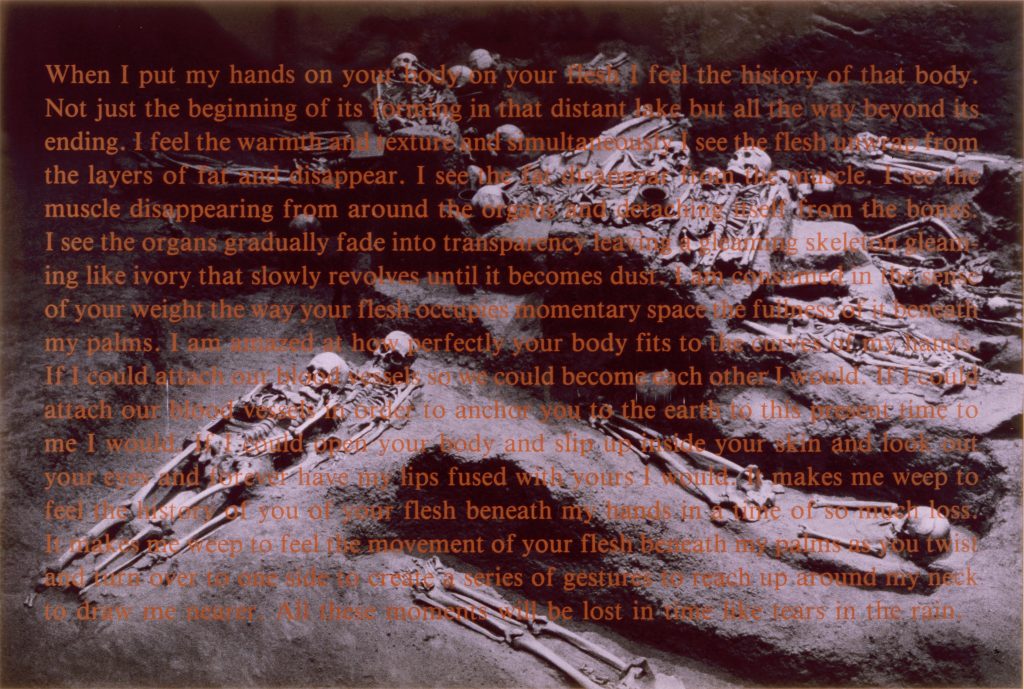

When I put my hands on your body on your flesh I feel the history of that body. Not just the beginning of its forming in that distant lake but all the way beyond its ending. I feel the warmth and texture and simultaneously I see the flesh unwrap from the layers of fat and disappear. I see the fat disappear from the muscle. I see the muscle disappearing from around the organs and detaching itself from the bones. I see the organs gradually fade into transparency leaving a gleaming skeleton gleaming like ivory that slowly resolves until it becomes dust. I am consumed in the sense of your weight the way your flesh occupies momentary space the fullness of it beneath my palms. I am amazed at how perfectly your body fits to the curves of my hands. If I could attach our blood vessels so we could become each other I would. If I could attach our blood vessels in order to anchor you to the earth to this present time I would. If I could open up your body and slip inside your skin and look out your eyes and forever have my lips fused with yours I would. It makes me weep to feel the history of your flesh beneath my hands in a time of so much loss. It makes me weep to feel the movement of your flesh beneath my palms as you twist and turn over to one side to create a series of gestures to reach up around my neck to draw me nearer. All these memories will be lost in time like tears in the rain.

Figure 4. David Wojnarowicz, When I Put My Hands On Your Body, 1990. Gelatin silver print and silk screened text on museum board, 26 x 38 inches. Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P∙P∙O∙W, New York ©Estate of David Wojnarowicz