The InQ13 POOC: A Participatory Experiment in Open, Collaborative Teaching and Learning

Jessie Daniels, Hunter College, CUNY School of Public Health, and the Graduate Center, CUNY

Matthew K. Gold, City Tech and the Graduate Center, CUNY

with Stephanie M. Anderson, John Boy, Caitlin Cahill, Jen Jack Gieseking, Karen Gregory, Kristen Hackett, Fiona Lee, Wendy Luttrell, Amanda Matles, Edwin Mayorga, Wilneida Negrón, Shawn(ta) Smith, Polly Thistlethwaite, Zora Tucker

Abstract

This article offers a broad analysis of a POOC (“Participatory Open Online Course”) offered through the Graduate Center, CUNY in 2013. The large collaborative team of instructors, librarians, educational technologists, videographers, students, and project leaders reflects on the goals, aims, successes, and challenges of the experimental learning project. The graduate course, which sought to explore issues of participatory research, inequality and engaged uses of digital technology with and through the New York City neighborhood of East Harlem, set forth a unique model of connected learning that stands in contrast to the popular MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) model.

Overview

Introduction

In the spring semester of 2013, a collective of approximately twenty members of the Graduate Center of the City University of New York created a participatory, open, online course, or “POOC,” titled “Reassessing Inequality and Re-Imagining the 21st-Century: East Harlem Focus” or InQ13. The course was offered for credit as a graduate seminar through the Graduate Center and was open to anyone who wanted to take it through the online platform. Appearing at a moment when hundreds of thousands of students were enrolling for Massively Open Online Courses (or MOOCs) offered through platforms such as Coursera, Udacity, and EdX, InQ13 was notable as an attempt to openly share the usually cloistered experience of a graduate seminar (typically comprised of 10–12 students and an instructor) with a wider, public audience. Exploring various aspects of inequality in housing and education, the course emphasized community-based research in a dynamic New York neighborhood through a range of “knowledge streams” and interactive modalities.

Developing, designing, launching, and running the POOC was an enormous undertaking on every level. In this article, we provide a conceptual framework for a “participatory” open course and share thoughts about the challenges inherent in translating the ordinarily private world of the graduate seminar into a shared, public, online experience. This article provides an overview of the background, structure, and theoretical underpinnings of the course; a discussion of its connection to East Harlem as the site of inquiry and learning; and a brief exploration of how we might begin to assess the impact of such an experiment. Befitting a course that brought together a widely diverse range of perspectives, the article features a multivocal reflection by many of its participants, including faculty, students, project managers, librarians, web developers, educational technologists, videographers, and community members. This experiment in participatory learning is further contextualized by a podcast related to our course.

The Context of the POOC

In order to understand the development of InQ13, which launched in early 2013, it is important to appreciate the particular historical and political moment in which the course emerged. The term “MOOC” —an acronym for Massively Open Online Course—was coined by educational technologists Dave Cormier and George Siemens in 2008 to describe an innovative, and inherently participatory, open, online course (Cormier and Siemens, 2010). In the fall of 2011, Stanford University opened some of its computer science courses to the world through an online platform and found hundreds of thousands of students enrolling. At about the same time, venture capitalists began pouring millions of dollars into businesses such as Coursera hoping to find a revenue model in MOOCs (The Economist, 2013). As a result, MOOCs moved from niche discussions among educational technologists to coverage in The New York Times, which proclaimed 2012 “the year of the MOOC” (Pappano, 2012). When we began development of InQ13, there was no shortage of hyperbole about MOOCs. In perhaps the most egregious example of this hype, New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman extolled the revolutionary possibilities of MOOCs, saying, “Nothing has more potential to enable us to reimagine higher education than the massive open online course, or MOOC” (Friedman, 2013). As a number of scholars have pointed out, such claims about the revolutionary potential of MOOCs are not unique in the landscape of higher education but instead harken back to similar, even identical, claims to those made about educational television in the middle of the twentieth century (Picciano, 2014; Stewart, 2013). Still, we were intrigued by the potential of digital technologies for opening education.

Premised on extending the experience of traditional university courses to massive audiences, MOOCs have provoked an array of responses. Commentators who believe that higher education is in need of reform argue MOOCs offer a productively disruptive force to hidebound educational practices (Shirky, 2014). According to such arguments, the educational experiences offered at elite institutions can now be made available to students across the world, for free, thus making higher education possible for students who would not otherwise be able to afford it. Some critics of MOOCs often view them in the context of a higher education system that is being defunded, worrying that higher education administrators see, in MOOCs, possibilities for both revenue generation through increased enrollments and cost-cutting through reduced full-time faculty hires (Hall, 2013).

To date, most MOOCs have consisted of video lectures, sometimes accompanied by discussion forums and automated quizzes. Students are expected to absorb and repeat information delivered via video in ways that seem consonant with what Paulo Freire described as the banking model of education, where students are imagined as empty vessels into which the instructor deposits knowledge (Freire, 1993). Within the mostly one-way communication structure of the truly massive MOOCs, the interaction between faculty members and students is necessarily constrained due to the scale. While some MOOCs attempt to foster interaction between the professor and his (or her)[1] students, this has not met with much success (Bruffet et al., 2013, 187). There is little in the corporate MOOC model to recommend it as a vehicle for a graduate seminar, in which intimacy and sustained discussion, rather than massiveness and openness, are most prized. We coined the neologism of “POOC” —a participatory, open online course—to better capture the meaningful participation and co-production of knowledge that we hoped to achieve. Our participatory approach was layered and nested, bringing together two interlocking components: 1) direct engagement with specific readings, people, neighborhoods, and technologies (Cushman, 1999; Daniels, 2012; Gold, 2012; Rodriguez, 1996; Scanlon, 1993); and 2) collaborative rather than individually-oriented community-based research projects.

Studying Inequality

The course focus on inequality grew out of discussions among faculty at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York (CUNY) about how to bring together research about inequality across disciplinary boundaries and extend those conversations beyond the walls of the institution in ways that mattered within communities.[2] There was wide agreement that any effort should find a way to engage with the vibrancy of New York City and its history of struggle for social and economic justice, and thus reflect CUNY’s public educational mission to “educate the children of the whole people.” Among the questions we hoped the course would explore were: What does inequality look like in 2013? How might we imagine our future differently if we did so collectively, across a variety of disciplines and in conjunction with community-based partners? And, given our particular historical moment, how might the affordances of digital technologies augment the way we both research inequality and resist its corrosive effects?

The Neighborhood of East Harlem

East Harlem is a neighborhood that has simultaneously fostered a vibrant, multi-ethnic tradition of citizen activism and borne the brunt of urban policies that generate inequality. Several of the people in the InQ13 collective had ties to East Harlem as residents, researchers, community activists and workers, so we began to discuss the possibility of locating the course there. In addition, CUNY had recently located a new campus in this neighborhood with the explicit goal of developing academic-community partnerships. These factors taken together—the unique history and present of East Harlem, the connection to the neighborhood from those in the InQ13 collective, and the new CUNY campus—provided a compelling case for situating the course in East Harlem. Thus, the original questions that framed the course were joined by another set of questions: Could a course such as this one “open” the new CUNY campus to the East Harlem community in innovative ways? Given the troubled relationship of university campuses to urban neighborhoods, could we forge different kinds of relationships? And, were there ways that the digital technologies used in the course could offer a platform that would be useful to community activists engaged in the struggle against the forces of inequality in East Harlem?

Given the limited amount of time the collective had to prepare the course and the complexity of staging the POOC, the process of forming in-depth engagements with community partners did not progress as far as we had initially hoped it would which will be further discussed (see Mayorga in “Perspectives” section). That said, the course served as a useful opening for future, ongoing efforts involving the East Harlem community at the uptown CUNY campus.

The Structure of the Course

The overall structure of the course was designed to serve multiple groups of learners: 1) traditionally enrolled students through the CUNY system, 2) online learners who wanted to participate, do assignments and complete the course, and 3) casual learners who wanted to drop in and participate as their schedule and desire for learning allowed.

In an effort to displace the MOOC model of a course led by a solitary, celebrity professor, each course session involved a guest lecturer or a panel of guests that served to highlight the collaborative nature of how knowledge is produced and activism is undertaken and sustained. Each session was both livestreamed for those who wanted to participate synchronously and then, several days later, a more polished video recording of the class session would be released and posted to the InQ13 course site for those who wanted to participate asynchronously. One of the ways we tried to build engagement with the East Harlem community into the structure of the course was to have class sessions that were also open community events at the uptown CUNY campus. Out of twelve regular sessions, four were held at the East Harlem campus and open to the public.

The course pivoted around leveraging digital technologies to enhance the skills and practices of community-based research; students were encouraged to work in partnership with community members in East Harlem. Students posted their completed assignments on the course blog at the InQ13 site. To facilitate group work, students could use the “groups” feature on the site to collaborate around specific projects. As designed, these groups were intended to foster connection between online-learners and CUNY-based learners, but this potential was not realized as fully as it could have been in the execution of the course. The faculty-provided feedback and grades on assignments were offered for CUNY-based learners, and the digital fellow provided this for the online learners (see Negrón in the “Perspectives” section below). At the end of the semester, students were invited to present their projects at a community event at La Casa Azul Bookstore in East Harlem (this was in addition to the four regular sessions held in the neighborhood).

Evaluating the Impact of the POOC

It is challenging to assess the impact of an experiment in graduate level education that took participatory learning as its chief goal. When the goal is for a course to be “massive,” the primary metric of evaluation is how many people registered for the course. With the POOC, this measure was not meaningful because participants were not required to register at the course site— a choice we made in our effort to open the course to as many different kinds of learners as possible. In its design and execution, the course allowed for multiple levels of participation, from Twitter users who joined conversations based on a Twitter hashtag (#InQ13), to those who watched the videos of the seminars or read some of the many open-access texts, to learners who created accounts and participated in group discussions on the course website.

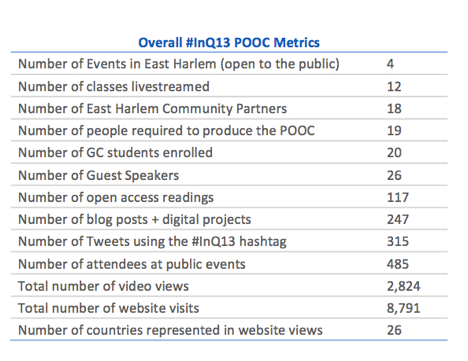

Figure 1. Evaluation Metrics of the POOC

Figure 1. Evaluation Metrics of the POOC

Part of the challenge of this experiment was the measurement of a broad spectrum of metrics meant to tap the distributed and participatory elements of the course (See Figure 1). For example, we were able to track the number of visits to the InQ13 course site during the semester, which totaled well over eight thousand (8,791). The videos garnered almost three thousand (2,824) views. While these numbers pale in comparison to the hundreds of thousands boasted by many MOOCs, these numbers represent a significant reach when compared to the usual reach of a typical graduate seminar that enrolls ten to twenty students.

Some of the emerging scholarship on evaluating MOOCs points to the importance of gauging student experience (Odom, 2013; Zutshi, O’Hare and Rodafinos, 2013). For the POOC, students contributed nearly two-hundred and fifty (250) individual blog posts and digital projects to the course site. A more in-depth qualitative analysis from the perspective of two students is included here (see Hackett and Tucker in the “Perspectives” section below).

Traditional measures of learning assessment are valuable, yet they often overlook the variety of learners and the wide range of their goals in engaging with such a course. Given the participatory nature of the course, one of the most relevant metrics is the number of people who attended the open events in East Harlem, which was nearly five hundred (485). As further testimony to the global potential of online learning, we found that people from twenty-six countries visited the course site or watched the videos. Discussions happened both in person and through the Twitter hashtag #InQ13 where over three hundred (315) updates about the course were shared.

We began the POOC with an emphasis on participatory pedagogy—on concrete interactions between a student community and a geographically specific urban community—all of which necessitated a model far removed from the sage-on-a-stage, “broadcast” teaching environments employed in most MOOCs. While MOOCs have spurred discussions about online courses extending the reach of higher education institutions (and, in the process, proffering new, more profitable business models for them), our experiences with InQ13 suggest that online courses that emphasize interaction between faculty, students, and broader communities beyond the traditional academy incur significant institutional and economic costs that rely on often hidden labor. The “Perspectives” section that follows is our effort to make legible this otherwise hidden labor.

PERSPECTIVES on the Participatory Open Online Course (POOC)

On the InQ13 website, our page about the collective lists nineteen different individuals who played a role in creating the course experience (http://inq13.gc.cuny.edu/the-inq13-collective). If MOOCs are imagined by administrators and venture capitalists to be a labor-saving, cost-cutting disruption for higher education, the POOC model was disruptive in another way. The POOC was, in reality, a job creation program, requiring significant investments of time, money, and labor to produce. Within the neoliberal context of devastating economic cuts to public higher education, this reversal of that trend points to an alternative model.[3] In the section that follows we offer insights from many of the people who were involved in producing the POOC and some lessons they draw from their particular roles and participation in the course.

Community Perspectives on the POOC

Community Engagement Fellow Edwin Mayorga

Our approach to community engagement drew on traditions of community-based research, where respectful collaboration with community is central to documenting the local and global dimensions of structural inequality. The commitment to centering community was intended to move us away from reproducing the often exploitative relationships between outside institutions and communities, setting up a number of challenges that we are still learning from. This sort of approach to community engagement is a timeintensive one, and one that was often at odds with the limited time frame for the launch of the POOC. Due to the experimental nature of the grant that funded this work, the POOC was conceived over the summer of 2012, launched in spring of 2013, but not fully staffed until late December – early January, 2013. Thus, building trusting relationships with community groups, effectively integrating community groups into course sessions, and connecting them with course students was a challenge that we did not always meet.

The strategy we used to engage community groups was to reach out to various organizations and host a community meeting. The initial community meeting, held at a restaurant in East Harlem, was small but productive. Following that, we worked to establish a relationship with the Center for Puerto Rican Studies (Centro). Centro’s place as a product of struggle, its long standing relationships to East Harlem, and its definitive archive of the Puerto Rican diaspora made it an ideal starting point for the course.

By the end of the course, we had much to be proud of with respect to our community engagement work. We were able to facilitate community-centered sessions at locations in East Harlem where researchers and activists who either live or work in East Harlem could speak to key issues affecting the community, such as education, housing, and gentrification. We were excited to see students who worked with various community-based organizations produce hundreds of knowledge streams in the forms of bibliographies, blogs, infographics, slides, visuals, and videos on issues of inequality both theoretical and specific to East Harlem, and open to any one to read, explore, and engage.

Still, there were a number of humbling setbacks. Most poignant were the critiques by community-connected scholars and participants about what they saw as reductive depictions of the community and the exploitative “parachuting in” of communityspeakers. We worked to address some of these important critiques by holding another community meeting, and reducing the number of organizations we worked with in order to ensure we maintained and nourished relationships with our project partners. To be sure, there was a need for more community-building work in the run-up to the course.

Upon reflection, our attempt to be both digitally and critically bifocal (paying attention to the local and the global— see, Weis and Fine, 2012) was ambitious and inadequately presented to community people. Creating a clear focus in partnership with communities is essential to future community-oriented POOCs. Most importantly, time (at least a year) and financial resources must be allotted to allow for the creation of well-considered opportunities to share and build across institutions, networks, and people.

The sustained work of community building can seem daunting, but it is central to providing a successful foundation for participatory social-justice education.

Faculty Perspectives on the POOC

Professors Caitlin Cahill and Wendy Luttrell

With a leap and a bound, together we held hands and dove head-first into InQ13 POOC. The course made history at the Graduate Center for it cross-listings across so many disciplines and programs (Urban Education, American Studies, Earth and Environmental Science, Psychology, Anthropology, Sociology, Geography, Women’s Studies, and Liberal Studies). We were not only aware of this cross-disciplinary breadth, but also the multiple groups and levels of learners as we developed graduate-level course readings and assignments. Our materials were posted on the public course platform so that all students could engage course materials and each other. Ensuring that these materials were open-access became a collective effort described below in more detail byPolly Thistlethwaite and Shawn(ta) Smith.

As instructors, we shared two goals: first, to frame the course as an inquiry into the links between public matters and private troubles (Mills 1959), or put differently, an inquiry into the structural inequalities and public policies that imbue our everyday lives. Our second goal was to marry community-based inquiry with digital technologies, in part to counter the no-placeness and too-smooth, ubiquitous, sanitized space of many online courses. We created a series of scaffolded graduate–level assignments for students to address how global restructuring takes shape in the everyday life struggles of a real place, engaging community-based research and digital technologies to learn and leverage change with East Harlem community partners.

Please turn off your cell phone

For the first assignment, students were asked to go to East Harlem without using any digital technologies. This felt like a bold move at a time when so much of our everyday experience is mediated by screens. We encouraged students simply to “be” in East Harlem, to draw upon their senses of smell, sight, sounds, touch, taste, and texture as they paid attention to and experienced their surroundings (Rheingold, 2012). As part of this assignment, we asked students to reflect upon their relationship to East Harlem and their positionality. For their final projects, students would experiment with at least three digital tools from a set of twelve categories (such as mapping, audio & soundscapes, and digital storytelling). But first, we needed to raise critical questions about the voyeuristic gaze of researchers engaging in working class communities of color. Through in-person and online discussions about personal experiences, readings, and the film Stranger with a Camera (2000), we began the course around questions of ethics, the politics of representation, and the meaning of community engagement. All of this was meant to prepare students to enter and engage East Harlem as a site of learning and activism, and tp set the tone for the explorations that followed.

On stage – off stage

Each week, the class met for two hours; during the first hour, we livestreamed video of a lecture or discussion as part of the public-facing course, and during the second hour, we met privately with the Graduate Center students. This was a key pedagogical move: we learned that the performativity of the POOC was intimidating for many involved, and so we were committed to maintaining dedicated face-to-face time each week with the Graduate Center students enrolled in the course. While some students were at ease in the online environment whether on camera, on the blog, or on Twitter, for others the public nature of working and learning was uncomfortable, even paralyzing. With hindsight, we wonder if this discomfort was even more pronounced after the sense-of-place exercise in East Harlem described above because it surfaced messy questions about insiders, outsiders, border-crossers, structural racism, anxiety, and attending to the necessary “speed bumps” of doing research where one must slow down and reflect before moving forward. This reflection was on-going and needed to be nurtured through multiple formats and spaces—weekly blog posts, class discussions on and off stage, one-on-one in-person conversations with students, meetings between students and community partners, and posts to a private online space where students could exchange views they didn’t want to share with a broader public.

Plurality of publics

Our experience builds out the pedagogical and ontological significance of acknowledging the plurality of publics. As Nancy Fraser (1996, 27) has suggested, the constitution of alternative public spaces, or counterpublics, function to expand the discursive space and realize “participatory parity,” in contrast to a single comprehensive public sphere. This was the promise of the POOC as we strove to create and hold different publics together. We believed in the productive tensions between digital technologies, community-based spaces and research, and the more intimate, reflective pedagogical spaces of the course. The course reflected these three dimensions in terms of format and ways one could participate. The community-based inquiry projects also placed emphasis upon using technology in exciting and interesting ways to feature the critical counterpublics of East Harlem and their emancipatory potential in addressing structural inequality and injustices. This was reflected in the variety of final projects, which focused on documenting contemporary and historical community spaces such as Mexican restaurants, Afro-Latina hair salons, alternative educational spaces, youth-led collective social justice movements (the Young Lords/ the Black Panthers), and the memories embedded in everyday spaces in El Barrio.

One of the most exciting ideas was how the POOC might serve as a resource at two levels: at the local level, connecting with members of different East Harlem community efforts, and at a global level, connecting with historic Latino neighborhoods (Barrios) across the US and around the world. For example, how might the POOC serve as a resource for undocumented students in Georgia or Arizona where access to education has been denied? Or how might it help trace networks of Puerto Rican migration across the United States? These remain potentialities for future iterations of the course; in this first instance of the course, the most developed form of participation came out of the community-based partnerships students formed through face-to-face relationships where the thorny questions of outcomes, sustainability, and representation were negotiated over time and in relationship.

On the edge of knowing

When we started the class, we did not know what to expect. We were wary of the online neo-liberalization of higher education, especially at this particular political moment. Still, we were excited by the possibilities of participatory digital technologies to create bridges that connect the plurality of publics in more collaborative rather than exploitative ways (as evidenced in some of the amazing student projects). Critical questions of appropriation, labor, access, pedagogy, and privatization loom large in our minds. But what stays with us is best conveyed by the wise words excerpted from the blog of Sonia Sanchez, a student in the course who wrote about the world we inherit but want to reimagine, a world where “everything can be turned around and stamped with a barcode,” including education, housing, and space. As Sonia points out, we are surrounded by screens, by “a million little vacuums with bright screens” that make people “unaware they are standing next to each other.” We see InQ13 as part of a larger and much-needed process of connecting screens and souls in the service of social, economic, and educational equity, and justice.

Open Access and the POOC

Librarians Polly Thistlethwaite and Shawn(ta) Smith

Libraries have traditionally supported faculty with course reserve services, copyright advice, and scanning service to shepherd extension of licensed library content for exclusive use by a well-defined set of university-affiliated students. However, under current licensing models, this content can rarely be extended to the massive, unaffiliated, undefined, and unregistered body of MOOC enrollees without tempting lawsuits filed by publishers with deeppockets. Course content, usually in the form of books, book chapters, articles, and films, are not licensed to universities for open, online distribution.

Additionally, use of licensed content of any kind is arguably incongruent with a MOOC’s aim and purpose. Licensed content requires some form of reader authentication to regulate access. In contrast, open-access scholarship requires no registration or license. It is available to any reader, including students affiliated with a university and non-university students living and working in East Harlem. Linking interested students to the open reports, films, books, and articles reflecting work focused on inequality and East Harlem, the POOC’s open access course materials raise the profile and increase the impact of the academic, activist, and artist authors.

Authors featured in or engaged with the InQ13 POOC were generally eager to make their work open access. The Directory of Open Access Journals verified that several significant course readings were already “gold” open access, providing the widest possible audiences, and ready to be assigned for any course reading. The Centro Journal of the CUNY Center for Puerto Rican Studies, for example, is completely open access. Many of this journal’s authors were assigned by the POOC over several course modules.

Some journals allow self-archiving by authors. Self-archiving means that authors may post their own articles online at their professional website or institutional repositories. These types of journals are sometimes referred to as “green” open access. While author self-archiving is widely permitted by traditional academic journal publishers, the opportunity to self-archive is not at all ubiquitously exercised or understood by authors. Authors publishing in journals that are not completely open (known as “gold” open access), required both prompting and advice about how to put their work in open access contexts. Librarians supporting the POOC spent a great many hours checking the policies of journals using the SHERPA/RoMEO tool, and corresponding with course authors about how to make their scholarship available in open access repositories, accessible by any student in the course.

A few book publishers were willing to make traditionally published, print-based academic books open access, at least temporarily. The University of Minnesota Press, NYU Press, and University of California Press made copyright-restricted book chapters, and in one case an entire book openly available to accompany an author’s video-recorded guest lecture.

Publisher restrictions are not at all immediately obvious to authors or to faculty forming course reading lists. Librarians played a crucial role in supporting this open online course by identifying, promoting, and advising faculty and their publishers about open access self-archiving.

Coordination of the POOC

Project Manager Jen Jack Gieseking

Producing the POOC involved a multitude of staff that across the span of InQ13’s development, enactment, and follow up. In order to manage the project’s many moving parts,we set about outlining our goals, sketching out a plan to accomplish these aims, and making sure each contingent piece was ready in time for the next element. In the few weeks we had to plan, we also involved educational technologists to help us think through user experience (UX) and information architecture (IA). They also helped us conceptualize the educational technology functions and support needed for InQ13 to succeed. The next step then was to hire staff to develop this work based on our colleagues’ expertise.

Oversight and management involves a great deal of listening. As project manager, I was responsible for seeing each element of the project to completion. For instance, as each person asked me, who would handle the UX or IA, I would turn around and assign that element to the person who already had a great deal of insight into it. Our work as co-developers involved many check-ins before any final work was completed so that we could bring together concerns and questions.

My own position bridged these parallel teaching and learning processes. I was simultaneously a developer, teaching assistant, online user, videographer, educational technologist, and the primary technical and logistic support for the live event seminars. I sometimes appear in the course videos because I invited the guest speakers for those weeks, or because someone was needed to run the laptop. I live-tweeted class sessions, I enrolled in the course, and, more than anything, I learned.

Each step forward in managing the POOC involved a million little, delicate steps. As Amanda Matles and Stephanie M. Anderson describe below, placing cameras in the classroom was a complicated issue that took weeks of discussion to resolve. Edwin Mayorga sent hundreds of emails requesting meetings with activists in East Harlem and making inroads to connect students to community partners. Our WordPress and Commons In A Box developer, Raymond Hoh, handled difficult fixes overnight and expanded the ways the site and course could afford a collaborative space for students and InQ13 team alike. Like the class itself, the process of producing the POOC involved a great deal of teaching, learning and knowledge-sharing.

Website development & Instructional Technology

Educational Technologists Karen Gregory, John Boy, Fiona Lee

There is a familiar heroic narrative about the genesis of new products and services in the tech sector (including educational technology) that goes something like this: “We worked 100 hours a week, slept under our desks, ate cold pizza and drank stale beer so we could write code and ship our product on time—and we liked it!” Like most heroic narratives, this narrative is as revealing for what it leaves out as for what it includes. While building a product, service or online course certainly requires concocting abstractions in the form of code, we have to unpack what we mean by “coding” in this context (Miyake 2013).

In addition to the time and energy that went into building the web infrastructure (setting up pages, categories, widgets etc.), there was a lot of discussion—online and in person—about course goals, envisioning what kind of work course participants would do and how they would use the site. In other words, the work of building the website was not just coding in the limited sense of creating and manipulating computer algorithms. It was also thinking, talking, debating, questioning, and imagining.

In this section, we will reflect our involvement, as graduate students, instructors and educational technologists, in building the POOC and highlight three forms of labor that are likely to be missed in the usual narrative: pedagogical practice, aesthetic imagination, and the accumulated labor of the “code base.”

We Came as Teachers

Perhaps the first thing to stress when considering the hidden labor of the website is that those of us who came together to create the site had already taught for several years. We did not come to this task as simply as “builders” or “coders,” but as educators, scholars, and Instructional Technologists. Each member of the site team was able to bring to bear several years of classroom experience, as well as experience collaborating with faculty across disciplines to design and implement “hybrid” assignments. This means that we not only had experience with what “works,” but also with what can fail, despite the designers’ (or teachers’) intentions.

The challenge of creating this particular course site was not only a challenge of designing a functional site to accommodate the coordination and logistics of the site (such as to create space for blogging or posting media artifacts), but also to lay out the site to structure, facilitate, and implement the course goals and intentions.

The Labor of Imagination & Design

In considering the question of labor, we cannot overlook the role the imagination played. Creating the POOC site was an act of giving form or realizing the ideas, goals, and desires for the course. If the POOC was to be a space for communication and conversation among participants, the challenge of this site was to imagine how to design a space that could foster community, across a series of mediated spaces and through the thoughtful use of the tools at hand, including WordPress and the Commons In A Box platform. At the same time, given that we were building the website for participants rather than for users, we had to re-imagine what “user experience” means. This required building a website that was not only functional, well organized and easy to navigate. The website also had to be designed in a way that encouraged participants to contribute their own ideas and goals for the course, and that was flexible enough to meet the course’s changing needs. To do so, we had to use our imagination to anticipate the perceptions and responses of participants, but in a way that remained open to their imagination of how they approached the course. In other words, the work of building the website did not just happen at the beginning, in anticipation of the start of the semester; it was an ongoing process of reflection and maintenance that involved engaging with participants’ needs.

The Political Economy of Service Provision

Another case in which we need to broaden our understanding of the kinds of labor coding entails is with regard to the tools or “code base” we worked with. Software products such as WordPress, BuddyPress, and the CUNY-developed Commons In A Box suite are not just abstractions all the way down; rather, they, too, are accumulations of people’s imaginative and creative work. To say that simply we built on or leveraged existing code bases is to reify this and to blot out the political economy of free and open source software (FOSS) development. While the FOSS world is often seen as the epitome of the “sharing economy” it also intersects in some ways with broader labor regimes. “FOSS development, with its flexible labor force, global extent, reliance on technological advances, valuation of knowledge, and production of intangibles, has fully embraced the modern knowledge economy” (Chopra and Dexter 2007, 20).

The Challenges of Videography

Videographers Amanda Matles and Stephanie M. Anderson

As doctoral candidates in the Critical Social Personality Psychology program, Geography program, and Videography Fellows at the Graduate Center, we entered the InQ13 POOC collaboration well acquainted with the nuances of using video in academic settings. The task in the POOC, though—to livestream, capture, and immediately publish the video recordings of the various classes online—presented a number of ethical, technical, and logistical challenges unique to participatory open online courses. Often, the introduction of camera equipment into any social space changes the dynamics and feelings of participants. While some students were comfortable having their likenesses seen by a mostly anonymous online audience, others expressed concerns, and anxieties. Thus, in order to achieve an intimate feel for online participants, consent from all students was needed. This tension of consent was compounded by the video crew’s presence in the midst of intimate group discussions. The feeling of embeddedness for online viewers sometimes came at the risk of vulnerability for graduate students, instructors, and speakers.

Working within the instantaneous time-space of participatory open online courses, the transmission of pedagogical material in video form—available in real time or overnight—is actually the result of professional A/V and computer set-ups and many invisible hours of planning and labor. Each location and unique class structure required specific A/V design. Because there were multiple presenters, audiences, rooms, and auditoriums, we needed not only a hardwire Ethernet connection in each location, but also flexibility and breadth in audio recording equipment. InQ13 used a two-person crew: one person operated the camera while the other live-mixed the audio, monitored the livestream, and received and reacted to feedback from other POOC collaborators watching the stream online. Additionally, an entire video postproduction process occurred within the 24 hours following each class. This included the addition of unique title cards and lower thirds for each speaker, sound mixing, exporting, file compression, and uploading new videos to the blog. Furthermore, long-format HD video files are extremely bulky, and can be slow to work with. Once edited, the file for a one-hour course usually takes at least 2 hours to export, then must be further compressed for internet streaming. The entire process could take up to 12 hours. A dedicated hard drive with at least 2TB storage and at least a 7200 rpm processor was needed to produce one semester of the POOC.

As videographers, we had to continually negotiate between what our ideals were and what was practically achievable given the opportunities and limitations involved in the InQ13 POOC. To integrate online POOC student participation and learning through the InQ13 site, it was vital that access to online course videos was timely. This availability allowed students writing weekly assignments and participating in blog conversations could torefer to the video archive at any time and as many times as needed. Online video provides learners with valuable repetition and open access.

The Labor of Supporting Students

Digital Fellow Wilneida Negrón

In the early planning stages of the POOC, the team identified the need for a Digital Fellow who could provide support in integrating technology and pedagogy to foster an active learning environment that would challenge students to think critically about inequality and the technologies they would be utilizing. The literature on best practices for online instruction increasingly emphasizes a focus on interactive, skillful use of technology, and a clear understanding of both technical and interpersonal expectations (Tremblay 2006, 96). The technology and participatory features of the POOC involved an online web platform, social media, and digital media technologies, the use of which bridged online and face-to-face learning contexts. This required me to partake in various roles as a facilitator, community-builder, instructional manager, coach, and moderator. While the fluidity of my role precluded, to some extent, clear parameters and role definitions, it also allowed for a kind of “distributed constructionism” (Resnick, 1996), a key building block to the formation of knowledge-building communities.

The initial phase of the class consisted of helping students and professors navigate around the multimodal nature of the POOC (see Kress, 2003) and evaluate any barriers or enablers when participating and using technology for content-creation, collaborating, and knowledge-building (Vázquez-Abad et al 2004, 239;Preece 2000, 152; Richardson 2006, 52). Since it was imperative that the students be able to utilize digital technologies, I conducted two short surveys, one completed in class and one completed online, which gauged the digital skills of students and their interest in a variety of digital tools they might use during the semester.

A majority of POOC students were interested in using Zotero, Flickr, and archiving-based projects for the class. This reflects what students already felt comfortable with, as many noted that the digital tools they most had experience with were Zotero and Flickr.

The majority of students expressed an interested in archiving but had no experience with it. Animation and information filters were the only two technologies that none of the students had experience in.

Although studies in computer-supported collaborative learning frequently under-expose the interaction between students and technology (Overdijk and van Diggelen, 2006, 5), my experience as a Digital Fellow revealed how essential this perspective is for identifying additional instruction and support needed. For example, through these assessments, I learned of the varying levels of digital media literacy among the students: some students were proficient and had been using digital technologies in their work and professional life, while others had no experience in digital technologies and/or limited use of social media. I sought to address these issues through individual and group instruction and through the creation of online groups and forums, which promoted peer-to-peer learning and problem solving.

As a Digital Fellow, I had to be prepared to negotiate the students’ own views about how they wanted to use digital technologies and their social media profiles. I could not assume, for instance, that all students would be at ease using these technologies, or that the asynchronous conversations between the graduate seminar students and the wider community of POOC students would go smoothly. Some students expressed early concerns about their privacy and seemed hesitant to use their public social media profiles in conjunction with the class. These kinds of moments provided challenges to the POOC’s objective of fostering transformative and open dialogue among students, but they were challenges that were met collaboratively by the InQ13 team.

Student Perspectives on the POOC: In the Physical Classroom

Student Kristen Hackett

Prior to taking the course I had a Facebook account as my sole scholar-activist digital outlet. Within the first couple of weeks I had set up an account with Twitter and Skype, had begun building a personal website, and was becoming an experienced blogger through my weekly contributions to the course blog. Further, within the first two months we had an assignment that required us to use three of the twelve knowledge streams suggested by the course in our community-based research projects, which ultimately entailed trying out many more than three before settling on which would be most useful (these along with instructions for use can be found at: http://inq13.gc.cuny.edu/knowledge-streams/).

In the course I used digital technologies to facilitate communication and collaboration with other classmates (both GC- and community-based), my professors, the distant guest lecturers, the extensive digital support staff, and community partners and organizations in East Harlem who were cruising the website or Twitter hashtag (#InQ13). In a broader sense, technology was used as an avenue to communicate to others and spread awareness about social justice—blurring the boundaries between community and academy and incorporating and implicating each in the other—and about our research projects, which were predicated on the importance of this cause. In this vein, Twitter was a useful tool for positioning our work among other similar works and related information by using targeted hashtags such as #communityresearch, #eastharlem, or #inequality. Furthermore, Twitter was important for driving others back to the site to learn more about the course and our cause by using the hashtag #InQ13 with each tweet.

On a level specific to my situation as a doctoral student, the emphasis on technology was useful in thinking about how I can expand the way I think about my scholarship and myself as a scholar. A specific question that has repeatedly come to mind during my graduate study is why journal articles and written prose are deemed the best (and often the only) mode of communication of our ideas. By introducing new tools of digital communication into my lexicon I could rethink or reimagine how I could communicate my research, in what form, from what platform, and to whom. For example, being able to incorporate Flickr photos into my blogs brings my words and thoughts to life in a way that is not achievable in a journal articles where images, and colored images in particular, are often not accepted. Additionally posting a short article to my webpage as a blog filled with photos and free of academic jargon, and then tweeting it to relevant yet potentially distant communities using hashtags allows me to share my work with others who I previously was not able to reach using traditional academic channels of sharing and publishing. In sum, the emphasis on these new and emerging technologies forced me to reconsider who my audience and co-researchers could, should, and might be and what forms that research could take.

Admittedly, given the highly supported environment we were in and the impending deadlines for assignments that required some kind of digital technology use, getting over our varying degrees of digital technology phobia occurred more rapidly and readily than others might expect. We had a few impromptu support group-like sessions in the beginning of the semester. At these sessions students voiced their fears of publishing online and putting their thoughts out there right away and/or their technical fears regarding actual use of a digital technology. Many of us didn’t have accounts for these different technologies and hadn’t engaged them before so our fears likely stemmed from a nagging anxiety about stepping into new territory.

For the former fear, some class time was carved out to talk, share, and support one another—and it helped that many of us were having the same concerns. When they were fears connected to lack of technical knowledge, we were referred to workshops in the library, or we could meet one on one with our digital technology support staff member or one of the librarians. In my own experience, my concerns were more along the lines of the latter, and while workshops and one-on-one sessions can be helpful in getting started, honestly a lot of my knowledge has come from doing and from playing around with the different technologies (for example, from building websites, from tweeting and using hashtags, and talking @ others on Twitter). Doing so alleviated the fear and increased the comfort of use as well as taught me how to use the different tools, technically speaking.

I also realized that part of my increased use of these digital technology tools was just knowing they existed. Furthermore, thinking about these tools in the context of rigorous academic research, and in a group that condoned and encouraged their use for that purpose, was new to me and reoriented my approach to these technologies in new ways—as tools. The focus of the course was not just on using these digital technologies, but using them as scholars and as scholar activists in pursuit of community-based research, and it was helpful that other respected scholars (our professors) and our academy were encouraging it.

Since the closing of the course I have proceeded to emphasize the use of digital technologies in my own scholarship and in the scholarship endeavors of research groups I work with. I have focused my efforts on Twitter and website and Facebook page creation at the moment. I think of the latter two in a geographical sense, as a way of creating a virtual place or home for me and my work, or the work of a research team. One can find my current research projects and interests, publications and presentations, and approaches to teaching. Further, they can get a sense of my networks by following links to the page of my research team or the Graduate Center, or the Environmental Psychology subprogram.

While my use seems to be growing, and I am finding the tools helpful, there are many digital tools from the course and in general that I’m not engaging. But I don’t think that’s the point. It is helpful just to know they are there, to be on the lookout for more as they develop, and to consider how they may enhance a project, make it more accessible or carry its messages further.

Student Perspectives on the POOC: In the Online Classroom

Student Zora Tucker

This course was valuable to me in several distinct but interdependent capacities: I am a graduate student at another institution, a public school teacher, and a self-identified movement activist. As a graduate student in a program in Arizona designed for people who live and work elsewhere, it was a windfall to find this course to use for my self-designed program in Critical Geography at Prescott College. It is rare that I am able to find collegial relationships in this rather isolated process, and the multiple modalities available to me—webcasts, Twitter, and the capacity to come into the CUNY Graduate Center for the open sessions—were all excellent for the development of my independent scholarship. I was able to see and converse with scholar-activists I had known only through writing, such as Michelle Fine and Maria Torres. This format allowed me to engage the course with varying intensities at different times in my schedule.

When I took this course, I was looking for teaching work as a new arrival to NYC while simultaneously doing research on charter schools and public space for my graduate work. This course gave me the ability to get a sense of the landscape of public schooling in relation to space in East Harlem, and to think through my emergent understanding of the state of public schooling in this city. My learning in these two areas came primarily from paying attention to people on Twitter, following them if our interests converged, and engaging with the work of other students posted on the class website. This happened fluidly, through a process that allowed my research interests to converge and weave together in a positive feedback loop that sustained my understanding of my new home, my academic critiques, and my ambition to work as a teacher in New York City.

This course was wellaligned with my movement philosophy of using academic space as a forum for broadcasting voices that are not always amplified in the halls of power. No one lives in the abstraction of neoliberalism; we all find our ways through the minutiae of its day-to-day realities. This course made space for this truth in multiple ways, but I will write here about two. First, the community forums created in InQ13 paired academic writing, which so often veers into the abstract and untenable, with the concrete analysis of those who do the work of living in and through sites of academic analysis. Second, the website itself was visible to people outside of the class, so I could share my posts and posts of other scholars—and even the structure of the website itself—with my former students, my colleagues, and anyone who might be interested in either the format or the content (or both) of this course. I had two colleagues at the college where I used to teach using my blog posts in their work with undergraduates.

In conclusion, s a person who came to this course through a friend who recommended it through Facebook, and as someone who participated in it primarily through the website and Twitter and shared it through social media—my experience of this POOC—a was holistically educational and useful beyond the expectations that I initially had of the experience.

Conclusion

We, the collective of the InQ13 POOC, shared what we learned while conducting this experiment in participatory, open education in the classroom, online, and among East Harlem community partners. As this essay suggests, and as the archived course website reveals, the InQ13 POOC was a valuable experience, not least of all because it offered an alternative to MOOCs at a crucial moment of their ascendance in the popular imagination. The InQ13 POOC provided a vision of digitally augmented learning that prizes openness, community-building, and participatory action above massiveness of scale. While this attempt to create an innovative model of what opening education could be sometimes resulted in messy struggles with the complex social, political, and economic issues related to inequality—not the least of which is the inequality between academics and community-partners—the POOC nevertheless reimagined what higher education might be if we took seriously the idea of “opening” education. Graduate education can and should engage with the possibilities to open education that MOOCs offer. But it must do so through thoughtful models, conceptualized with social justice in mind, and with an awareness of the labor, solidarity, and collectivity required behind the scenes. We proffer the InQ13 experiment in particular, and the idea of the POOC more generally, as one possible path for others considering future experiments in open education.

Bibliography

Bruff, Derek O., Douglas H. Fisher, Kathryn E. McEwen, and Blaine E. Smith. 2013. “Wrapping a MOOC: Student perceptions of an experiment in blended learning.” MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching 9 (2): 187–199. Accessed November 5, 2013. http://jolt.merlot.org/vol9no2/bruff_0613.htm. OCLC 61227223.

Chopra, Samir and Dexter, Scott D. 2007. Decoding Liberation: The Promise of Free and Open Source Software. New York: Routledge. OCLC 81150603.

Cook-Sather, Alison. 2013. “Unrolling Roles in Techno-Pedagogy: Toward New Forms of Collaboration in Traditional College Settings.” Innovative Higher Education 26, no. 2 : 121-139. OCLC 425562481.

Cormier, Dave and George Seimens. 2010. “The Open Course: Through the Open Door–Open Courses as Research, Learning, and Engagement.” Educause Review 45, no. 4 : 30-39. http://www.educause.edu/ero/article/through-open-door-open-courses-research-learning-and-engagement

Cushman, Ellen. 1999. “The public intellectual, service learning, and activist research.” College English: 328-336. OCLC 1564053.

Daniels, Jessie. 2012. “Digital Video: Engaging Students in Critical Media Literacy and Community Activism.” Explorations in Media Ecology, Volume 10 (1-2): 137-147. OCLC 49673845.

(The) Economist. 2013. “Higher Education: Attack of the MOOCs.” July 20, 2013. The Economist. Accessed July 23, 2013. http://www.economist.com/news/business/21582001-army-new-online-courses-scaring-wits-out-traditional-universities-can-they. OCLC 1081684.

Fraser, Nancy. 1996. “Social Justice in the Age of Identity Politics: Redistribution, Recognition, and Participation.” Paper presented at The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, Stanford University April 30–May 2. Accessed November 10, 2013. http://tannerlectures.utah.edu/_documents/a-to-z/f/Fraser98.pdf. OCLC 45732525.

Freire, Paulo. 1993. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum. OCLC 43929806.

Friedman, Thomas. 2013. “Revolution Hits the Universities.” The New York Times, January 26. Accessed January 26, 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/27/opinion/sunday/friedman-revolution-hits-the-universities.html. OCLC 1645522.

Gold, Matthew K. 2012. ” Looking for Whitman: A Multi-Campus Experiment in Digital Pedagogy.” Digital Humanities Pedagogy: Practices, Principles and Politics, ed. Brett D. Hirsch. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers. OCLC 827239433.

Graham, Charles Ray. 2006. “Blended learning systems: Definition, current trends, and future directions.” In Handbook of blended learning: Global perspectives, local designs edited by Curtis Jay Bonk and Charles Ray Graham, 3–21. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer. OCLC 60776550.

Hall, Richard. 2012. “For a Critique of MOOCs/Whatever and the Restructuring of the University.” Accessed May 12, 2013.

http://www.richard-hall.org/2012/12/05/for-a-critique-of-moocswhatever-and-the-restructuring-of-the-university/.

Kress, Gunther R. 2003. Literacy in the new media age. London: RoutledgeFalmer. OCLC 50527771.

Mills, Charles Wright. 1959. The Sociological Imagination. USA: Oxford University Press. OCLC 165883.

Miyake, Keith. “All that is Digital Melts into Code.” 2013. GC Digital Fellows Blog. October 25. Accessed October 25 2013. https://digitalfellows.commons.gc.cuny.edu/2013/10/25/all-that-is-digital-melts-into-code/.

Odom, Laddie. 2013. “A SWOT Analysis of The Potential Impact of MOOCs.” In World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications, vol. 2013, no. 1: 611-621. OCLC 5497569520.

Orner, M. 1992. “Interrupting the calls for student voice in liberatory education: A feminist poststructralist perspective.” Luke, C. and G. J. (eds.). Feminisms and critical pedagogy. New York: Routledge. OCLC 24906839.

Overdijk, Maarten and Wouter van Diggelen. 2006. Technology Appropriation in Face-to-Face Collaborative Learning. Workshop at First European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning, Crete, Greece, October 1–4. Accessed November 16, 2013. http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-213/ECTEL06WKS.pdf. OCLC 770966463.

Palloff, Reena M., & Pratt, Keith. 1999. Building learning communities in cyberspace: Effective strategies for the online classroom. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. OCLC 40444568.

Parr, Chris. 2013. “MOOC Creators Criticise Courses’ Lack of Creativity.” Times Higher Education. October 17. Accessed May 8, 2014. http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/news/mooc-creators-criticise-courses-lack-of-creativity/2008180.fullarticle. OCLC 232121645.

Picciano, Anthony. 2014. “The Hype, the Backlash, and the Future of MOOCs,” pp.6-9, University Outlook. February. Accessed May 12, 2014. http://universityoutlook.com/archives.

Powazek, Derek M. 2002. Design for community: The art of connecting real people in virtual places. Indianapolis, IN: Pearson Technology Group. OCLC 47945525.

Preece, Jenny. 2000. Online communities: Designing usability and supporting sociability. Chichester, UK: Willey. OCLC 43701690.

Tremblay, Remi. 2006. “Best Practices” and Collaborative Software in Online Teaching. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 7(1). http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/309/486. OCLC 424760690.

Resnick, M. 1996. Distributed constructionism. The proceedings of the international conference on learning sciences. Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education. Northwestern University. OCLC 84739865.

Rheingold, Howard. Net Smart: How to Thrive Online. MIT Press. Cambridge, MA, 2012. OCLC 803357230.

Richardson, Will. 2006. Blogs, wikis, podcasts, and other powerful web tools for classrooms. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. OCLC 62326782.

Rodriguez, Cheryrl. 1996. “African American anthropology and the pedagogy of activist community research.” Anthropology & Education Quarterly 27, no. 3: 414-431. OCLC 5153400850.

Sanchez, Sonia. “More than panem et circenses.” 2013. Reassessing Inequality and Reimagining the 21st Century. April 18. Accessed November 5, 2013. http://InQ13.gc.cuny.edu/more-than-panem-et-circenses/.

Scanlon, Jennifer. 1993. “Keeping Our Activist Selves Alive in the Classroom: Feminist Pedagogy and Political Activism.” Feminist Teacher, 8-14. OCLC 424819999.

Stewart, Bonnie. 2013. “Massiveness+ Openness= New Literacies of Participation?.” Journal of Online Learning & Teaching 9.2. Accessed May 12, 2014. http://jolt.merlot.org/vol9no2/stewart_bonnie_0613.htm. OCLC 502566421.

Straumheim, Carl. 2013. “Masculine Open Online Courses.” Inside Higher Ed, September 3. Accessed November 5, 2013. http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/09/03/more-female-professors-experiment-moocs-men-still-dominate. OCLC 721351944.

Vázquez-Abad, Jesus, Nancy Brousseau, Guillermina Waldegg C, Mylène Vézina, Alicia Martínez D, Janet Paul de Verjovsky. 2004. “Fostering Distributed Science Learning through Collaborative Technologies.” Journal of Science Education and Technology, 13(1): 227–232. OCLC 425946303.

Vázquez-Abad, Jesus, Nancy Brousseau, Guillermina Waldegg C, Mylène Vézina, Alicia Martínez Dorado, Janet Paul de Verjovsky, Enna Carvajal, Maria Luisa Guzman. 2005. “An Approach to Distributed Collaborative Science Learning in a Multicultural Setting.” Paper presented at the Seventh International Conference on Computer Based Learning in Science, Zilina, Germany, July 2–6. Accessed November 13, 2013. http://cblis.utc.sk/cblis-cd-old/2003/3.PartB/Papers/Science_Ed/Learning_Teaching/Vazquez.pdf

Weis, Lois and Michelle Fine. 2012. “Critical Bifocality and Circuits of Privilege: Expanding Critical Ethnographic Theory and Design.” Harvard Educational Review 82(2): 173–201. OCLC 815792737.

Zutshi, Samar, Sheena O’Hare, and Angelos Rodafinos. “Experiences in MOOCs: The Perspective of Students.” American Journal of Distance Education 27, no. 4 (2013): 218-227. OCLC 5602810621.

[1] Most high-profile MOOCs have featured men as instructors; the POOC was co-led by two women. For more on the gender imbalance in MOOCs, see Straumheim 2013.

[2] This initial conversation included Michelle Fine, Steven Brier and Michael Fabricant and was made possible by the Advanced Research Collaborative (ARC), under the thoughtful leadership of Don Robotham (Anthropology).

[3] The POOC was made possible by funding from the Ford Foundation.

About the Authors

Jessie Daniels is Professor of Public Health, Psychology, and Sociology at Hunter College, CUNY School of Public Health, and the Graduate Center, CUNY. She has published several books, including Cyber Racism (2009) and White Lies (1997), along with dozens of articles. She leads the JustPublics@365 project.

Matthew K. Gold is Associate Professor of English and Digital Humanities at City Tech and the Graduate Center, CUNY, where he serves as Advisor to the Provost for Digital Initiatives. He is editor of Debates in the Digital Humanities (2012) and served as Co-PI on the JustPublics@365 project during its first year.

Co-Authors from the InQ13 Collective:

Stephanie M. Anderson

(Graduate Center, CUNY)John Boy

(Graduate Center, CUNY)Caitlin Cahill

(Pratt Institute)Jen Jack Gieseking

(Bowdoin College)Karen Gregory

(Graduate Center, CUNY)Kristen Hackett

(Graduate Center, CUNY)Fiona Lee

(Graduate Center, CUNY)Wendy Luttrell

(Graduate Center, CUNY)Amanda Matles

(Graduate Center, CUNY)Edwin Mayorga

(Swarthmore College)Wilneida Negrón

(Graduate Center, CUNY)Shawn(ta) Smith

(Graduate Center, CUNY)Polly Thistlethwaite

(Graduate Center, CUNY)Zora Tucker

(Prescott College)