Introduction

In Radiant Textuality: Literature after the World Wide Web, Jerome McGann presents a fictional dialogue between two allegorical figures, “Pleasure” and “Instruction.” Instruction complains of the hypocrisy of teaching poetry, particularly in its “pretense to freedom of thought,” in which the “discussion” between teacher and students is often guided by the agenda of the teacher (McGann 2001, 33). In response, Pleasure suggests a return to Susan Sontag’s proposal in her famous essay “Against Interpretation” which calls for an “erotics of reading” through the act of recitation: “Let’s get back to the words, to the language—to the bodies of our thinking. I’m ‘against interpretation,’ I’m for recitation” (McGann 2001, 33). Here, rather than ask students to explain what they think the poem means (which, according to Pleasure, is often a guessing game about what the teacher wants to hear), the students spend most of their class time reading the poems out loud. By “performing” the poem through recitation, Pleasure explains, students manifest the poem’s formal arrangement in sound, “something like the way musicians interpret a piece of music by rendering the score” (McGann 2001, 31). As the first chapter of McGann’s book, which sets the stakes of his intervention, this dialogue demonstrates quite literally how form—“the words … language … bodies of our thinking”—matters in interpretation (2001, 33). By making the students complicit in its re-creation, Pleasure and Instruction finally agree, performing poetry is the best way to teach it.

The practice of recitation, of reading poetry out loud, is a time-honored hermeneutical engagement between the student and literature in print. It is widely deployed in English classrooms to scaffold the activity of close-reading, or the thoughtful, critical analysis of a text that builds from significant details or patterns toward meaning. This paper questions how teachers might facilitate this kind of close analysis in the digital age. If rendering a musical score is an apt analogy for reading printed poetry out loud, a suitable analogy for engaging with texts on a screen might be the act of looking through a microscope or a telescope, which drastically changes the viewer’s vantage of the textual object. According to some literary critics, however, the shift in perspective provided by electronic formats evacuates the reader’s critical encounter with text. Mark Hussey, one of the editors of the digital archive Woolf Online, warns that many digitization efforts run the risk of disenfranchising readers who are limited by the way they interact with texts on a screen. Hussey explains, “The activity of reading is altered when the embodied process of turning the page is replaced by swiping, clicking, searching, or typing” (Hussey 2016, 268). Though he appreciates the accessibility that digital archives (like Woolf Online) provide, other kinds of digital projects “require vigilant implementation to avoid the potentially reductive effects of readers becoming users” (264). Hussey’s concern that engaging with texts through a screen will make reading too easy is complemented by an alternative concern—that it will make things too difficult. Many instructors remain reluctant to incorporate tools that create steep learning curves for their students. According to the Pew Research Center, the worry over the “digital divide,” which has largely focused on access to technology (those who have versus those who have not), now includes a new metric, digital readiness (Horrigan 2016). As technology continues to proliferate, the question increasingly shifts to whether digital resources are sufficiently intuitive for learning. For instructors then, technological useability is a double-edged sword—either digital resources will be so user-friendly that they evacuate the demands of close-reading, or they will be too complex to offer pedagogical benefits.

One way instructors in English might grapple with the useability concern is to approach the digital interface itself as site for criticism. Offering their own telescope metaphor, Geoffrey Rockwell and Stephen Ramsay explain that digital projects and tools might function as “telescopes for the mind” (Rockwell and Ramsay 2012). By presenting information in a certain form, they explain, such projects make interventions on the act of seeing, and turn vision into a framework for theorizing. With digital archives and editions, for example, the display and appearance of the interface inflects the user’s interpretation of its contents. Such an interface might include an option for annotating the text and reading another’s annotations, or it may include a search bar that allows readers to search for keywords. These “social-reading” or “deep-searching” interfaces visually filter the textual object to both guide and provoke analysis on the text. Adopting Rockwell and Ramsay’s optical analogy, then, teachers might use digital resources for the way they change the way that readers “see” literary texts to reveal new hermeneutical possibilities.

However, Rockwell and Ramsay are quick to point out that the opacity of technological processes presents an obstacle for assessing how such processes work. Their argument extends the concern about digital readiness in the classroom to one about critical potency of digital tools. When a digital tool’s construction is opaque to the user, who operates at several levels of remove from the underlying computational processes, it presents a paradox for practicing criticism: “The only way to have any purchase on the theoretical assumptions that underlie a tool would be to use that tool. Yet it is the purpose of the tool (and this is particularly the case with digital tools) to abstract the user away from the mechanisms that would facilitate that process” (Rockwell and Ramsay 2012). Here, the very technology that allows the scholar to “see” the object in a new way also prevents her from examining how this “visual” process works. The authors offer the example of a simple concordancing tool, which aggregates repeated words in a text into frequency lists. Although this word aggregator makes an implicit argument about the unity of a text and the author’s intentions, its underlying technology remains inaccessible to anybody using the interface (Rockwell and Ramsay 2012). It seems that, to be pedagogically effective, digital resources should be intuitive to use and offer insight into the technology used to create the resource. The question then becomes how one might experience the shift in perspective that a tool provides while accessing the underlying technical processes that power the tool. For close-reading instruction, then, the resource needs to present an intuitive interface that addresses its own construction.

This paper assesses digital projects in English for how they deploy critical interfaces for reading that make explicit both the formal qualities of the source text and the computational tools or methods that engage those formal qualities. I examine the fine line between critically inhibitive and critically productive interfaces of two very different digital projects: first, a full-text collection of transcribed writings, encoded for smooth search and online reading, and second, a text analysis tool that instantly visualizes textual data into graphs, charts, and lists. I will frame my discussion on the pedagogical benefits of each project with more of McGann’s speculations from Radiant Textuality about the potential of close and critical engagements with texts in online environments. McGann’s first point, implied by the dialogue between Pleasure and Instruction, is already assumed as my first criterion—that digital projects in English studies ought to explicitly engage the formal (and therefore embodied) qualities of literature, attending to what Sontag calls the “erotics of reading.” Additionally, his points about deformance, “quantum poetics,” and speculation (examined below), will situate my approach for using online resources in the teaching of close-reading. These points together suggest how an interface can model and activate textual form for literary criticism, presenting a “telescope for the mind” that offers glimpses into its underlying technological processes.

Toward a Quantum Poetics

McGann, who writes nearly 20 years before Rockwell and Ramsay, has a positive take on the issue of technological opacity. Rather than aim to understand how a digital tool works, McGann emphasizes how the tool unleashes meaning. The unique affordance of digital environments, according to McGann, is that they allow for numerable interventions upon the textual object. Just as reading poetry out loud “embodies” its formal qualities through vocal activity, so digitizing a text opens it up to various levels of formal manipulations. In the chapter “Deformance and Interpretation,” McGann and Lisa Samuels coin the term “deformative criticism,” which describes any activity that distorts, disorders, or re-assembles literary texts to discover new insights about its formal significance and meaning. They offer Emily Dickinson’s proposal of reading a poem backwards as a key example of deformative criticism. Here, “the critical and interpretive question is not ‘What does the poem mean?’ but ‘How do we release or expose this poem’s possibilities for meaning?” Active first and contemplative later, deformance aims to “disorder … one’s senses of the work,” estranging the reader from the familiarity of the text (McGann 2001, 108). By privileging performance over intellection, this method regards “theory” as secondary, demoting it to an afterthought of practice.

McGann’s proposed framework of deformance opens the text to new interpretive possibilities. In his chapter, “Visible and Invisible Books in N-Dimensional Space,” McGann speculates that engaging with texts on a computer could be as intimate a process as engaging with them on paper, but with more sophistication and efficiency. Readers may not only have a “handle” on the object, but also be able to manipulate and transform it in virtually infinite ways. Ideally, the tool should work alongside the reader’s intuition, as a “prosthetic extension of that demand for critical reflection,” by which the reader is able to feel her way through the text (McGann 2001, 18). The tool could also be equipped to process literature from a variety of perspectives, addressing the different qualities of the text that emerge during the reading process. McGann introduces the term “quantum poetics” to indicate the volatile potentiality for meaning contained in every element of a literary text. He explains that, “Aesthetic space is organized like quantum space, where the ‘identity’ of the elements making up the space are perceived to shift and change, even reverse themselves, when measures of attention move across discrete quantum levels” (McGann 2001, 183). The meaning of particular words in a literary text depends upon a multitude of factors, from antecedent readings and pathways through that text, to the significance of immanent elements such as typography and blank spaces, all of which the reader can only process a limited amount. In its potentiality, McGann asserts, “Every page, even a blank page … is n-dimensional” (2001, 184). Accordingly, digital tools could expose literature’s inherent potentialities by carving new paths across familiar texts. In this way, McGann argues for tools that facilitate tactile and intuitive engagements of texts within an environment that opens itself up to multiple dimensions of reading.

Digital tools that “deform” text to reveal its quantum potential operate within a speculative mode of criticism. In his chapter, “Editing as a Theoretical Pursuit”, McGann explains how his development of a print edition of Lord Byron’s works and the digital edition of the Rossetti Archive influenced his thinking about the different critical possibilities between print and digital editions. Paper-based editions, according to McGann’s experience, are inadequate and limited, and newer editions often “feed upon and develop from [their] own blindness and incapacities” (McGann 2001, 81). By contrast, digital editions can be designed for complex, reflexive, and ongoing interactions between reader and text. Indeed, “[a]n edition is conceivable that might undertake as an essential part of its work a regular and disciplined analysis and critique of itself” (McGann 2001, 81). Here, McGann explains that, because transforming print text into electronic forms necessarily “deforms” the text, changing one’s view of the original materials, each act of building the edition calls its original purpose into question. McGann points out that his work on the Rossetti Archive brought him to repeatedly reconsider his earlier conception and goals, asserting that the “Rossetti Archive seemed more and more an instrument for imagining what we didn’t know” (2001, 82). The technical experience of editing electronic texts encourages the speculation on new potentialities about its presentation.

If the digital tool attends to a text’s form or the potentiality for formal manipulations, the result of interacting with it will always be unpredictable. In allowing the reader to “imagine what [she] do[esn’t] know” (McGann 2001, 18), deformative criticism relies on speculation, which implies a certain level of ignorance. The reader does not need to know where her deformative experiments will lead, nor does she need to understand the underlying computational processes that facilitate her experimentation. Instead, her focus ought to be on the present unfolding of the text (what Pleasure calls “recitation”) in the current unleashing of its quantum poetics. Thinking back to the telescope metaphor—as long as a telescope allows for experimentation, for switching in and out of focus, one need not break it open to see how it works. The reader’s ignorance here, if addressed thoughtfully, can be conducive to learning: free of the technical details about the text, she can focus on how the process of reading unleashes new meaning. As I begin to review of the following digital projects and tools, therefore, I will examine how the reader’s experience with the interface hinges on the balance between ignorance and discovery. My attention to the text’s current deformance, rather than an “ideal” or comprehensive version of the text, will suggest further ways that editions might fulfill their objectives or enhance the formal unities that are already evoked. What do these projects reveal about the “n-dimensional” qualities of their textual objects? How do their formal unities productively play on ignorance to lead readers to imagine what they don’t know? And how might the editors and developers enhance this revelatory process? My examination finds that the pedagogical benefits of digital resources stem from an interface that both makes explicit the text’s formal elements and encourages the reader to interact and experiment with these elements. In some cases, such benefits rely on the extent to which the projects engage not only with the source text, but with their own technical modeling.

Women Writers Online

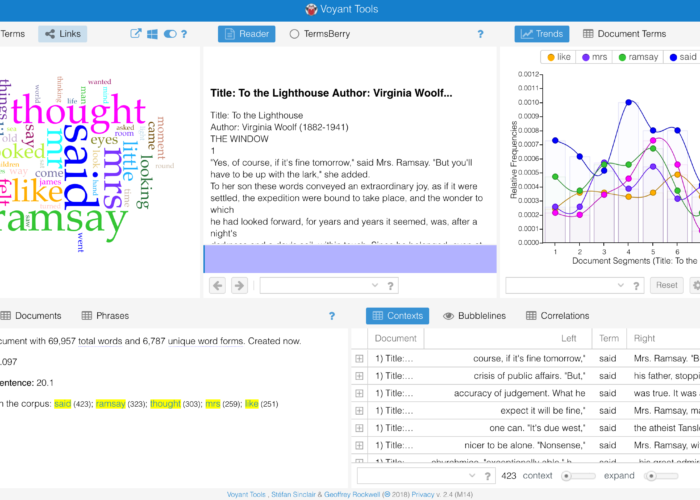

The first project is Women Writers Online (WWO), a digital archive by the “Women Writers Project,” which collects unfamiliar texts by underrepresented women writers between 1400 and 1850 (Women Writers Project 2016). Active for nearly 30 years, the project is maintained by Julia Flanders, Director of the Digital Scholarship Group at Northeastern University, and its senior programmer, Syd Bauman. In 2002, Flanders remarks that “Even now, most people—certainly most students—could name, if asked, only a handful of women writers active before 1830” (Flanders 2002, 50). WWO aims to correct this deficiency by offering hundreds of transcribed and encoded primary text documents, which users can search and read directly on their screens. WWO’s most impressive feature is this browsing interface that facilitates corpus navigation across various “panes” from the large textbase to the individual object (Figure 1). The “search pane” contains a search box and filters that allow the user to narrow results according to genre and date. The “results pane,” in the middle of the page, contains a list and timeline of the search results, which appear as full texts on the “text pane,” on the right side of the page. In moving from the left to the right side of the screen, the user progresses from keyword to specific text. This browsing interface allows her to sift through a large corpus in order to find something very specific.

Considering this search capability, the project’s most effective feature is its facilitation of discovery. Here, the handling of the search results, which eases the reader’s “zooming in” across results and chronology to the individual text, enacts the critical shift in perspective described by Rockwell and Ramsay’s telescope metaphor. Browsing through these search results engages the reader in online research that is smoother and more controlled than most academic or archival databases. To demonstrate the scholarly potential of the search functionality, a number of supplementary resources of the project operate alongside main website. Flanders asserts that,

The pedagogical aims of the Brown University Women Writers Project (WWP) go back to its very origins; at its core, the WWP aims to improve teaching. In a deeper sense, however, this attempt arises from a relocation of the ground of teaching. That is, the project attempts to make student work more like that of professionals in the field; it attempts, in short, to make learning more like research. (2002 49)

To “make student work more like that of professionals,” the WWP collects and publishes projects based on student research on WWO. It presents various “Exhibits” of work that supplement and contextualize the topics and texts in the database. These projects highlight fledging scholars’ engagement with the results of their searches, using the texts as a starting point for further research. Another resource, the “Lab,” is an “experimental area” for the WWP developers, where they can explore the encoded XML data in the form of visualizations. The resulting “prototypes” consist of graphs, diagrams, and maps of the texts, accompanied by a description of the original source, computational processes, and suggestions for further research. In one example that compares the ratio of male to female speakers in two seventeenth-century plays, the author explains that, “these at-a-glance comparisons can serve as the starting point … perhaps prompting questions about the different motives, audiences, and dramatic conventions shaping the two works” (“Visualizing Speakers in Drama by Gender” n.d.). The editors explain that some of these prototypes may eventually be incorporated into the functionality of the WWO website. (“WWO Lab” n.d.).

Despite these resources, the WWO interface misses an opportunity to fully engage its potential for discovery by obscuring its own encoding. The editorial statement emphasizes the source texts as static, informational objects: “We treat the text as a document more than as a work of literature … As a result, we do not emend the text or create critical or synthetic editions; each encoded text is a transcription of a particular physical object” (“Methodology for Transcription and Editing” n.d.). The editors further assert how the interface presents the various texts on an even level, resisting traditional organizational schemes. As Flanders and Jacqueline Wernimont point out, one of the major interventions of the project is the way it dissolves generic categories: “The WWO search tools bring into a single view texts that conventionally fall into political, literary, dramatic, and imperial history genres … generat[ing] a different, more intimate experience of boundaries and their constructedness” (Wernimont and Flanders 2010, 428–9). While this documentary and democratic approach for presenting texts facilitates the navigation from corpus to object, the interface might account for the relationships within the corpus in ways that further the project’s goal of resisting traditional categorization for its individual texts. Instead of presenting the archive according to a tree structure, which progresses from keyword to results to individual texts, the project might engage contextual information within the individual texts, reflecting a more complex network of information about them. To explore these contexts, the project ought to reveal some of the information encoded by the editors onto the text. Encoded information includes anything from descriptions of authors, cultural references, or key features of the text. For those who are unfamiliar with encoding, and particularly with TEI encoding (the method used by the WWP), it is a standard method for marking up texts in large-scale digitization projects in the humanities. By making explicit the underlying models that structure the individual texts, the interface would encourage the reader to sustain a deep reading within the primary document itself. Doing so would also allow the project to take full advantage of the extensive editorial work already begun by the WWP, who go through the long and arduous process of encoding a text for digitization.

In particular, revealing the TEI would enhance the activity of close-reading within the individual texts. Considering the project’s aim to recover women’s writing, it ought to attend to how the intellectual and technical labor that comes with creating such a resource determines a reader’s engagement with that resource. Because the encoding work for WWO is inaccessible behind a clean interface, readers cannot know the many of the key features about the source text. Drawing attention to the encoding (which remains completely obscure to the casual user), would inform how modeling these texts for digital formats implicitly affects meaning-making. For example, using TEI, editors “tag” the structural, renditional, and conceptual elements of text, including elements such as paragraphs breaks, emendations, and personal or cultural references. In an editorial statement on the WWP website, the editors explain that “A single encoded transcription can be used to produce many different forms of output, and in a sense many different ‘editions.’ The current presentation of these texts represents one of these possible editions” (“Display Conventions for the Women Writers Online Interface” n.d.). The editors assert that this presentation prioritizes “readability,” and as such, suppresses many elements in the visual output which are originally encoded into the text:

In general, we have tried to present the information needed to grasp the visual language of the text—font shifts, alignment, and so forth—in a way which will also provide flexibility for an effective and consistent display on the web. The display you see in WWO represents some aspects of the source text fairly closely (such as capitalization and italics) but regularizes or suppresses others. (“Display Conventions for the Women Writers Online Interface” n.d.)

Besides “printed page numbers and most forme work,” the exact nature of the suppressed elements remain obscure to the reader (“How to Use the WWO Interface” n.d.). The editors do not fully account for them in their editorial statements, nor do they make publicly available any of the XML files that describe the encoding. These files likely contain various elements would bear on interpretation and thus would be of use for close-reading activities. In fact, in a 2013 article for this journal, Kate Singer demonstrates how TEI can be used to teach close-reading to undergraduates. Her students’ painstaking work in tagging elements such as metaphor “reframe[s] reading as slow, iterative, and filled with formal choices” (Singer 2013). In modeling textual elements, encoding makes explicit the ways that digitizing and editing a text instills a specific reading or interpretation of that text. Speaking on TEI projects more general, Singer points out that, “Because XML encoding often hides itself from view, TEI editions can give students a type of double-blind reading, where they can see a supposedly transparent document and then examine the editing and marking underneath” (Singer 2013). By revealing some of this underlying encoding work, WWO would more effectively facilitate an engagement with what McGann calls a text’s “quantum poetics.” The search function of the interface would unravel new avenues for discovery within the individual texts in the corpus.

Voyant Tools

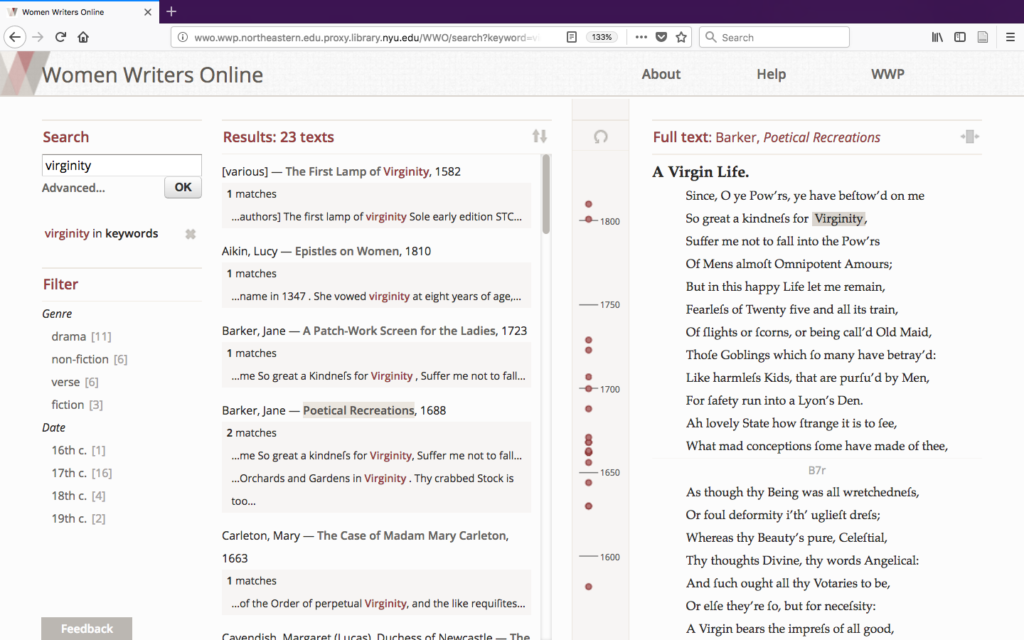

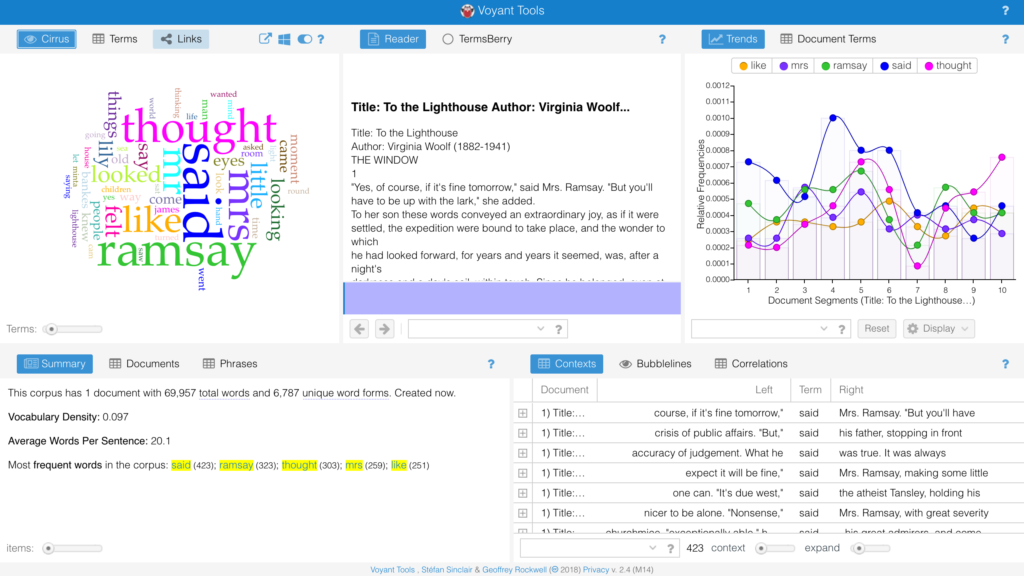

Diverging significantly from archival forms, Voyant Tools is a web-based application that facilitates text analysis in real time, in the form of instant, dynamic visualizations of textual data (Rockwell and Sinclair 2016b). Developed by Geoffrey Rockwell and Stéfan Sinclair, both humanities professors, this website offers a powerful, open-source tool that processes text into a variety of visualizations on word frequencies, contexts, and networks. In keeping with the free and open principles of software development, Voyant Tools synthesizes software from existing open-source libraries, and the final product has affinities with older text exploration and analysis projects developed by Rockwell and Sinclair, Hyperpo and TAPoRware, respectively. Voyant also offers extensive documentation, including a statement of design principles, tutorials for major features, individual descriptions of each tool, and directions for how to export and reference work. The major principles included in the design statement are “scalability,” to facilitate large corpus sizes and processing speed, “ubiquity,” for quick and convenient integration, and “referenceability,” to encourage attribution and incorporation of the tool in scholarly work (Rockwell and Sinclair 2016a). In keeping with open-source principles, the project is “extensible,” allowing for the addition of new tools as well as the adaptation of existing ones (Rockwell and Sinclair 2016a). Overall, Voyant shows a concern not only for functionality and ease of use, but also for placing the tool within a larger critical conversation and developmental trajectory in textual analytical methods.

However, the tool’s primary interface on the homepage obscures this documentation to encourage immediate experimentation with the tool. The link to the documentation is small and understated, tucked beneath the blank text box that takes up the center of the page, along with a bright blue button that reads “Reveal.” The design of the interface thus reinforces McGann, Rockwell, and Ramsay’s insistence on praxis as a hermeneutic. This prioritization of the text box prompts exploration, where users are invited to jump in without fully knowing how the tool functions. Additionally, a banner across the top of the page reads “see through your text,” heralding the mysterious results of computational text-analysis. In leveraging the user’s ignorance about how the tool works (through complex javascript code), the interface draws her attention toward the possibility for seeing text in a new way. The Voyant developers explain that the tool ideally functions within a larger hermeneutical process: “We feel strongly that text analysis tools can represent a significant contributor to digital research, whether they were used to help confirm hunches or to lead the researcher into completely unanticipated realms” (Rockwell and Sinclair 2016a). Through an interface that catapults the user onto a page of near-instant visualizations of the text, the intricate workings of the tool fade beneath its dazzling effects.

Voyant therefore resembles, in the words of Rockwell and Ramsay, a “‘telescope for the mind’ that presents texts in a new light” (Rockwell and Ramsay 2012). In doing so, however, the tool also subjects itself to accusations of what Dennis Tenen calls “blind instrumentalism”; Tenen asserts that “tool[s] can only serve as a vehicle for methodology. Insight resides in the logic within” (Tenen 2016). To clarify what he means, Tenen offers his own telescope metaphor, which resurrects the familiar problem of opacity as a barrier to critical thinking. Tenen supposes that a group of astronomers use a telescope without fully understanding how it works. Due to their ignorance, they fail to notice that it is broken, and can only reveal faulty images of the heavens, which the astronomers take as fact. He concludes: “To avoid receiving wondrous pictures from broken telescopes … we must learn to disassemble our instruments and to gain access to their innermost meaning-making apparatus” (Tenen 2016). According to Tenen, the user must understand the workings of the tool in order to learn from it. Those who do not understand how a tool functions remain disempowered, reduced to the motions of the tool. They resemble something like Hussey’s readers of digital texts—critically limited by the vacuous activities of clicking and swiping.

However, in the case of Voyant, the attention to technical inner-workings actually precludes the subtle and embodied interaction with the tool. Tenen’s warning about “blind instrumentalism” might be followed by McGann’s point about the critical value of ignorance, which can actually propel the user toward more complex and insightful meditations. We may thus revise Tenen’s telescope metaphor: though a broken telescope might mislead the viewer as to the location of the stars, the process of using it could reveal something about the workings of light. In this sense, the significance of the telescope is not what it does to the viewer’s perspective, but how it engages the user in process of discovery (Rockwell and Ramsay 2012). One of the most compelling benefits of Voyant is how it defamiliarizes habits of reading, particularly close-reading. Compared to the WWO interface, Voyant more directly facilitates reading as a meaning-making activity that relies on formal manipulations of text. As soon as the user uploads the text onto the site, she can interact with the visualizations by moving, adding, or deleting elements as she pleases. Reading then becomes a modeling activity, which engages the user in a sustained act of formal experimentation—the digital equivalent of Pleasure and Instruction’s “reading out loud” as a pedagogical strategy. Here, Voyant assists close-reading by drawing attention to the formal elements of the text as a foundation for critical analysis.

Conclusions

For those who really want to learn about the inner workings of the tool, they can always refer to the extensive documentation. But for those who want to experiment right away, the obscurity of computational methods opens a space for critical interventions, in which experimentation resembles something akin to criticism. My examination of Women Writers Online and Voyant Tools suggests that the most effective tools can make productive use of the user’s unfamiliarity with technology, as long as these tools thoughtfully deploy their underlying technical process to engage the formal qualities of the text at hand. For digital projects in English studies, there is a fine line between obscuring and harnessing the technical construction of these resources, which relies on the extent to which these projects use their interfaces to address textual form. In the case of WWO, offering access to the encoding models would enhance the already robust interface to engage the implicit formal qualities of the digitized text. Voyant, by contrast, builds its critical interventions directly into the deployment of a highly sensitive and easy to use interface. The differences between the two projects present a space for teachers to consider the effects of inhibitive and productive interfaces in the English classroom.

In particular, teachers need to be clear about the formal aspects of literature that they want to teach. In assessing whether the interface stifles or engages these aspects, they might look to the ways that it evokes technical modeling or active experimentation as methods for close-reading text. In some cases, they might approach technological opacity as an opportunity for learning about textual form. Accordingly, they ought to consider questions that might not immediately occur to an English instructor: What level of comfort or knowledge with technology is necessary for their students? Do students need to see (or gain some exposure to) the encoding/coding that underlies the reading surface? How might this exposure change traditional close-reading pedagogy? I offer two suggestions, seemingly contradictory. First, by seeing the code—having access to both the linguistic form of the text and its theoretical and technical underpinnings—the students gain purchase over the structures that determine meaning-making. This method relies on modeling. Second, by not seeing the code, students harness their own ignorance as a condition for learning, an ignorance that propels them toward the new and unforeseen. This method relies on experimentation, and like modeling, it hinges on the close attention to textual detail. After all, as Pleasure and Instruction remind us, human beings can only consciously process one thing at a time. Reading poetry out loud works well as a pedagogical strategy because it forces the student to focus her attention on her present, unfolding path through the text. Why engage digital interfaces to do the same?