Charlie Edwards, New York City College of Technology

Jody Rosen, New York City College of Technology

Maura A. Smale, New York City College of Technology

Jenna Spevack, New York City College of Technology[1]

Abstract

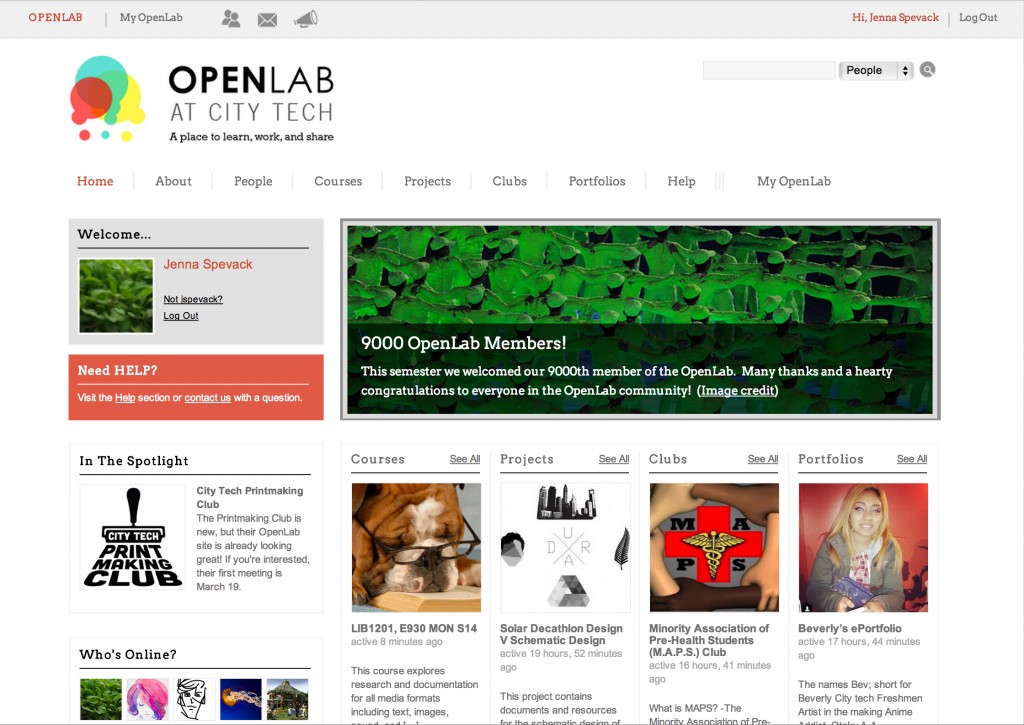

For the Fall 2011 semester, New York City College of Technology (City Tech) launched the OpenLab, an open digital platform for teaching, learning, and collaboration that everyone at the college—students, faculty, and staff—can join. Built by a City Tech-based team using the open source software WordPress and BuddyPress, it provides a space where members can connect with one another in an academic social network, create profiles and portfolios, and collaborate in courses, projects, and clubs, sharing their work with others at City Tech and beyond. As its name suggests, the OpenLab is both open on the web and a place for experimentation. It is also experimental itself, in its goals to increase student engagement and reduce fragmentation at a large, diverse, and sometimes impersonal commuter institution. What we have seen so far is promising: in only two years the OpenLab has already become an essential part of the life of the college with, at this writing, over 9,400 members. This article traces the path that led to the creation of the OpenLab, shares successes, challenges, and lessons learned along the way, and outlines future plans. We invite readers, and visitors to the OpenLab, to consider what creating such a space—open, shared, experimental, and democratic—might achieve at their own institutions.

The OpenLab in Context

Institutional challenges

City Tech is a senior college of the City University of New York (CUNY), the largest urban public university in the U.S. The college has gone through several transformations since its founding in 1946 as a trade school, most importantly when it joined the CUNY system in 1964 and when it became a senior college—awarding both Associate and Baccalaureate degrees—in 1983 (New York City College of Technology n.d.b). City Tech offers a wide range of professional and technical programs including engineering, computing, architectural and construction technologies, hospitality and tourism, communication design, and the allied health sciences, as well as a variety of general education and upper-level courses in the liberal arts and sciences.

Students at City Tech differ from the popular media image of the traditional American undergraduate in several important ways. There are no residence halls available at the college, and, like most CUNY undergraduates, the majority of City Tech students live in New York City with their parents, guardians, or other family members. The college is a majority-minority serving institution, with self-reported race/ethnicity at 34% Hispanic, 32% Black, 20% Asian/Pacific Islander, and 11% White students. Just over half of City Tech students report a household income of less than $30,000 per year, and just under half are in the first generation of their families to attend college. Like undergraduates at other commuter colleges, City Tech students often have responsibilities in addition to their studies; they may work part- or full-time, or provide care for children or other family members (CUNY Office of Institutional Research 2012, New York City College of Technology 2012).

Enrollment at the college has soared in recent years; by Fall 2012 the college enrolled over 16,000 undergraduate students, almost two-thirds of whom attend full-time (CUNY Office of Institutional Research 2012). While its location, in busy Downtown Brooklyn adjacent to the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges, facilitates easy access via public transportation, the density of the neighborhood constrains opportunities to enlarge the college campus. A much-needed new building is currently under construction, though its completion is not anticipated until Spring 2017. Meanwhile there is a lack of attractive, communal gathering space at City Tech: there are few lounges for students to use to socialize, relax, or study, no quadrangle or lawns, and only one small outdoor space.

City Tech’s student body, then, is constantly in motion between home, work, and school, with limited opportunities to make connections with and at the college—though such connections are key to student success.

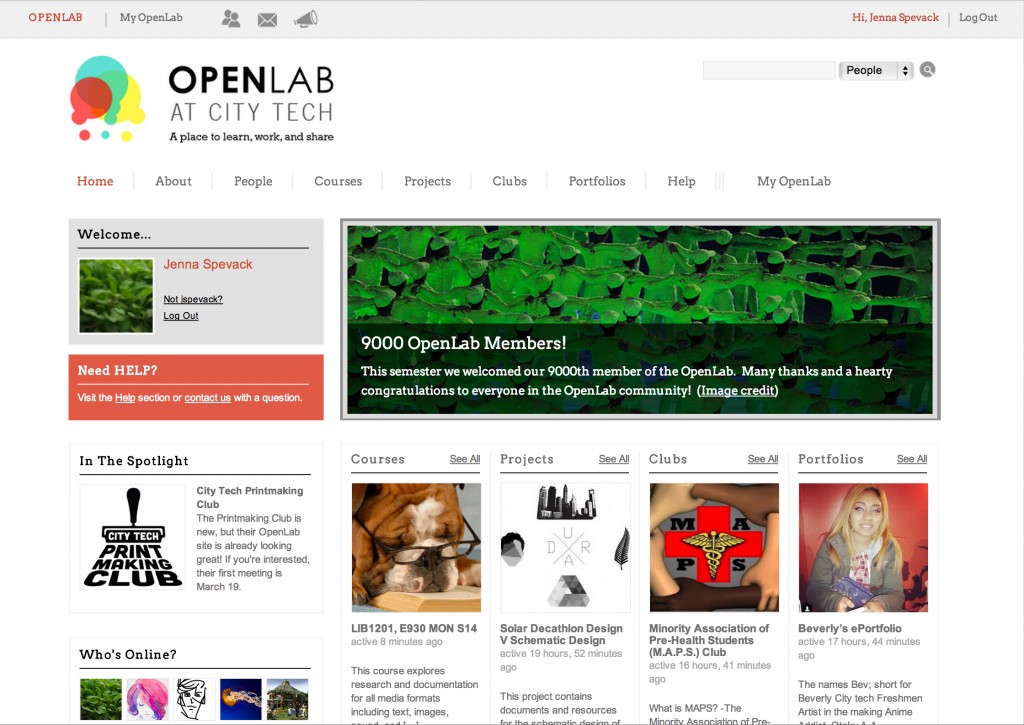

Figure 1. OpenLab Home Page (click for full-size image)

Figure 1. OpenLab Home Page (click for full-size image)

A living lab

The OpenLab is a major component of “A Living Laboratory: Revitalizing General Education for a Twenty-First Century College of Technology,” a five-year project (2010-2015) funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of Education’s Title V Strengthening Hispanic-Serving Institutions program.[2] The Living Lab project aims to improve student engagement, specifically by addressing the difficulties that students encounter in making connections between their required General Education courses and the highly specialized coursework in their majors, even as these courses function as gateways to their fields. The project seeks to collaborate with groups throughout the college to re-envision General Education across the disciplines by using City Tech’s Brooklyn waterfront location as a living laboratory, employing place-based learning and the hands-on modes familiar to our students in their majors to increase student achievement, measured by grades and persistence, retention, and graduation rates.

The OpenLab was conceived as a key element of the Living Lab project that would both support the Living Lab’s goals and seek to address these larger institutional challenges of disconnection and fragmentation by strengthening the college’s social and intellectual fabric. As an open digital platform the OpenLab can make the college curriculum visible to City Tech students, and encourage them to make connections among their strengths, interests, and goals. The OpenLab creates avenues for community members in different classes, departments, and schools to connect with one another. It offers a virtual place for students, faculty, and staff to meet and work and an opportunity to strengthen the college community unfettered by the limitations of our physical plant. The OpenLab provides virtually through its online platform what the City Tech campus cannot always provide physically: a beautiful, inspiring space for communities to gather and grow.

Why Open? Why Lab?

The name OpenLab speaks to two important and pervasive themes of this initiative. Its open nature fosters community and connection. Unlike closed online systems such as Blackboard, the learning management system available throughout CUNY, the OpenLab allows members across the college to communicate with one another and the world outside City Tech. OpenLab membership is available to everyone at City Tech through a simple registration process. Members can see what other members are doing, as can visitors from outside of the City Tech community. Such openness has great potential. This open-by-default design provides greater transparency for students looking to see what goes on in other courses, offering them a unique insight into their choices for registration and choosing a focus or major. Faculty members can benefit from the innovative pedagogies their colleagues employ, and can see not merely which courses their students have enrolled in but also what they study in those classes. Staff members can get a glimpse into course activities that would not otherwise be accessible to them. For all members, the possibility of observing and participating in curricular, co-curricular, and extracurricular activity is an exciting prospect, one that is only possible because the system is open.

As a college of technology, City Tech uses throughout its curriculum a laboratory model that is both familiar to and successful for its students. The OpenLab fosters the kind of learning espoused in the City Tech mission statement, developing both intellectual curiosity and practical experience in career fields by creating active, hands-on, and process-oriented experiences. In so doing it pairs with the college’s educational goals for the students to apply problem-solving skills to their work in their professions and develop communication skills (New York City College of Technology n.d.a), fostering intellectual curiosity and practical experience in career fields. All members of the OpenLab—students, faculty, and staff alike—benefit from the opportunities for experimentation available to them through use of the tools it provides: blogging capabilities, collaborative documents, shared discussions, and the ability to integrate external tools easily and seamlessly. By using WordPress for content creation, OpenLab members gain valuable experience with software they will likely encounter again, whether for work or in their own extracurricular pursuits. We encourage students specifically—and all OpenLab members in general—to take advantage of the expertise they can develop in using WordPress, and to promote it as a skill when they move on from City Tech.

The OpenLab, in adopting the open source software WordPress and BuddyPress as its foundation, joins a worldwide laboratory of open source design and development. In creating the OpenLab, the team has been fortunate to build on the experiments and experiences of others at City Tech, CUNY, and beyond who have implemented WordPress and BuddyPress as open pedagogical tools over the past decade. The open digital platform that the OpenLab is most similar to is the CUNY Academic Commons, an academic social network launched in 2009 that connects faculty, staff, and graduate students across all 24 campuses of CUNY (the team has recently released the Commons In A Box, which puts a full-featured WordPress and BuddyPress implementation within reach for any institution). The OpenLab team also counts as inspiration UMW Blogs, built at the University of Mary Washington by Jim Groom and his team, and the University of British Columbia’s WordPress installation spearheaded by Brian Lamb. We have learned from WordPress projects at other CUNY colleges as well, including Baruch College’s Blogs@Baruch, Macaulay Honors College’s and York College’s student ePortfolio platforms, and Queens College’s undergraduate writing initiative. In building the OpenLab as a place for community at City Tech, then, we are proud to join a community of educators and technologists dedicated to opening education through the use of free and open source software and a commitment to open pedagogical practices.

The OpenLab in Theory

In addition to the strong lineage of inspiring open source projects that paved the way for the OpenLab, the project has theoretical grounding centered on the idea of student engagement as critical to ensuring that students are successful in their college careers (Kuh et al. 2007, xi). Certain pedagogical and social practices contribute to and bolster student engagement; these include frequent interaction between students and faculty, especially outside of class time, both academic and social interaction with peers, feedback received from faculty in a timely manner, and “time on task”—the amount of time students spend on their academic work (Kuh et al. 2007, 43). Further, a strong engagement with the college community may be especially important for commuter students such as those at City Tech, who spend less time on campus than do undergraduates at residential colleges (Krause 2007, 29).

Research also indicates that technological interventions like the OpenLab have the potential to strengthen student engagement at commuter institutions (Krause 2007, Kinzie et al. 2008). The OpenLab offers a platform for faculty-student and student-student interaction in courses and extracurricular activities, as well as multiple avenues for faculty and peer feedback on student work in a variety of media. Since the OpenLab is a web-based platform, the ability to accomplish coursework while off-campus may also increase the amount of time that students spend on their academic work. With the multiple responsibilities that our students navigate throughout their days in addition to their coursework, the opportunities for 24-hour, off-campus access to the OpenLab may be especially beneficial.

The OpenLab can also have an impact on student engagement beyond flexible access to coursework. Recent data collected for the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE), which samples over one million students at hundreds of four-year colleges and universities about their participation in programs and activities for learning and professional development, reveals that engagement rose among “[f]irst-year students who frequently used social media to interact with peers, learn about campus events and opportunities, and interact with faculty and advisors” (National Survey of Student Engagement 2012, 18). While the NSSE asked students about proprietary social media platforms, this finding corresponds with the observations of those working with open academic social networks. Matthew K. Gold, for example, notes that these platforms provide multiple pathways for connection via what he terms “low-stakes engagement”: “Students may visit the course site because they receive a friend request from a fellow student, and in visiting the site, they may quickly respond to a status update, contribute a link to a group, respond to a forum post, send a private message, or update their own status” (Gold 2011, 70-1). These academic social networks provide multiple avenues to attract students into a course, and in doing so can strengthen their ties to the college community.

The OpenLab can foster opportunities for our students to work and study together, to encourage each other, and to support each other’s success, which is far less likely when students do not know or feel connected to one another. Beyond this, though, as Gold and Otte report in their discussion of the CUNY Academic Commons, faculty and staff members too can similarly benefit from working with a platform that encourages collaboration, a networked structure that encourages interdisciplinary, intercollegial, and nonhierarchical conversations (2011, 10). Such a structure, however, does not come about automatically when WordPress is installed; rather, it is the result of conscious design choices made with community-building in mind.

Design of Place: Structure and Features

Customizing for community

The OpenLab and much of its user-created content is open and visible to the public, allowing prospective members and site visitors to browse and comment. Although only members of the City Tech community can join the site and actively create content, the site structure and home page content feed invite visitors to experience the dynamic learning environment and community that is not always visible on the physical campus.

BuddyPress, the open source social networking software integrated into the OpenLab’s WordPress Multisite installation, allows us to define a virtual place that supports City Tech’s community-building needs and provides the infrastructure necessary for an active, high-impact, connected learning environment. It offers social networking features like activity streams, member profiles, group and site creation, discussion, and collaborative document editing, and is at the core of sibling sites such as the CUNY Academic Commons. BuddyPress powers one of the most distinctive features of the Commons, its home page, which highlights recent activity by members, groups, and blogs, and gives visitors an instant snapshot of the vibrant Commons community. This integration of members and their activity, and the collaboration and cross-pollination it fosters, inspired the OpenLab’s home page design and organization.

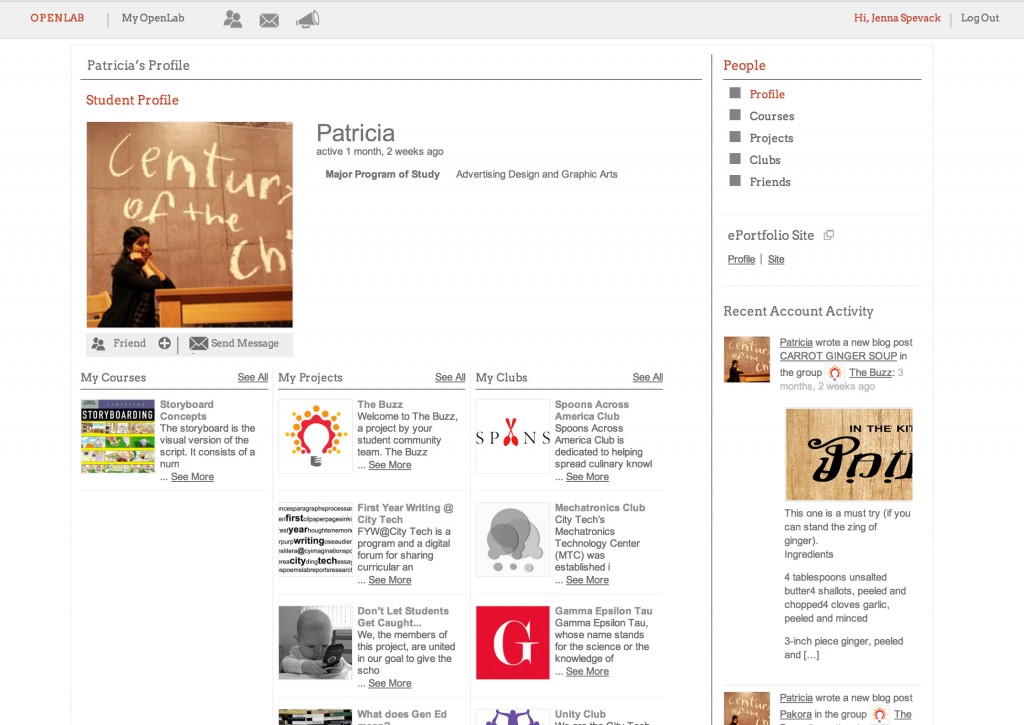

Figure 2. OpenLab “Group” configuration: Courses, Projects, Clubs, and Portfolios

Figure 2. OpenLab “Group” configuration: Courses, Projects, Clubs, and Portfolios

There are, however, significant differences between the OpenLab and its sibling installations. The biggest modification, implemented in partnership with our consulting developers, was to customize BuddyPress and subdivide its default “Group” configuration into several discrete types, Courses, Projects, Clubs, and Portfolios:

- Projects on the OpenLab can range from student research projects and collaborations to college committees to grant-funded academic journals, and can be created by individual or multiple members.

- Clubs allow any member of the College community to grow an online space related to a particular social or academic interest.

- Courses are set up to offer faculty members the tools to facilitate class collaborations, engage students in meaningful peer-to-peer learning, and provide a digital repository for course documents.

- Portfolios are an extension of the College’s student ePortfolio initiative and allow for personal portfolio development for all OpenLab members, including faculty and staff. The member Portfolio is a WordPress or external site linked to the member Profile page. Members are encouraged to use the site to present their teaching, academic, or creative work.

These appear prominently in the navigation, along with People, the OpenLab’s directory of members. This organizational architecture supports usability and navigational aesthetics and facilitates group creation, interaction, and findability by separating groups into defined areas of focus that are familiar to our college community. This important customization helps to communicate a clear path for visitors and offers a foothold for members less experienced in open, collaborative systems.

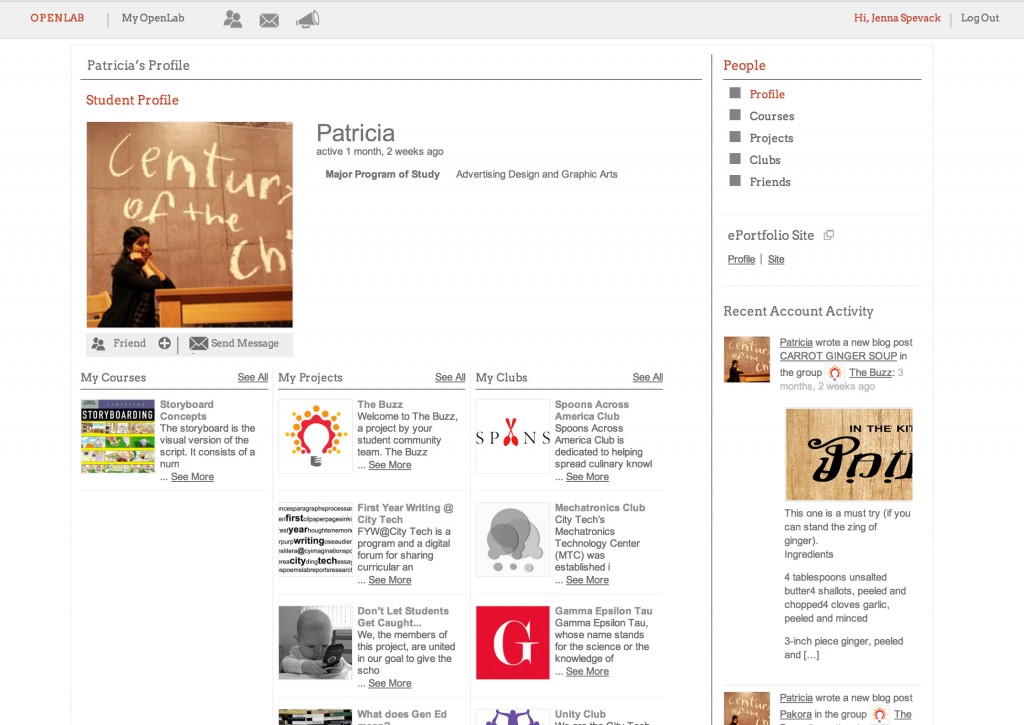

Figure 3. OpenLab People Page

Figure 3. OpenLab People Page

The People section of the OpenLab brings together all our members—students, faculty, and staff—and provides access to their Profiles. Any member of the campus community with a City Tech email address may sign up and create a Profile on the OpenLab.[3] The member Profile presents the member’s academic interests, department or area of study, and contact information, as well as recent activity on the OpenLab including posts, comments, and discussion topics. Profile visitors can view the Projects, Clubs, and Courses that the member participates in, allowing them to make connections with others who have similar interests and providing opportunities to share learning, social, and research experiences with the greater OpenLab community. The member Profile also allows for a pseudonymous display name and allows the member to choose the information they share with others. Use of pseudonyms allows members to protect their identities without compromising the public nature of the OpenLab. We believe that giving members control over their self-presentation is an essential component of any open platform.

Figure 4. OpenLab Member Profile

Figure 4. OpenLab Member Profile

The benefit of the OpenLab’s customized navigational sections is that it gives new or prospective members a place to start: browsing these general areas guides the member who might be interested in joining a campus club or seeing an example of a member Portfolio. Although not all groups on the OpenLab are public, those that are present the most recent data on the group Profile page. Although the OpenLab encourages openness, it also supports a range of fine-grained privacy options that enable groups to have public or private spaces as desired, and even a combination of the two. Each group Profile, similar to the member Profile, displays recent posts, discussions, collaborative document activity, group membership, and a link to the group’s associated WordPress site.

Listening to Campus Voices

The OpenLab team follows an iterative approach to design and development, the standard open source software methodology. After releasing a version of the site, we listen for feedback from members and observe how they embrace or ignore new features. Critical here is the work of the OpenLab’s Community Team.[4] All are advanced graduate students with expertise in both the technical and pedagogic aspects of using open source platforms in an educational context. Some of their work takes place behind the scenes: testing site updates, reporting bugs, evaluating and recommending plugins and themes, and developing the OpenLab’s Help content. They are also the friendly faces of the OpenLab, answering members’ questions via email and online, running workshops, visiting classrooms and offices, and maintaining open channels of communication between the OpenLab’s members and the rest of the team.

This community-minded method of development accepts the unpredictability of member needs and behaviors and allows the OpenLab to evolve as the community grows and develops. Following are several examples in which member requests and actions have translated directly into exciting new functionality and have greatly improved the design of the OpenLab as place to learn, work, and share.

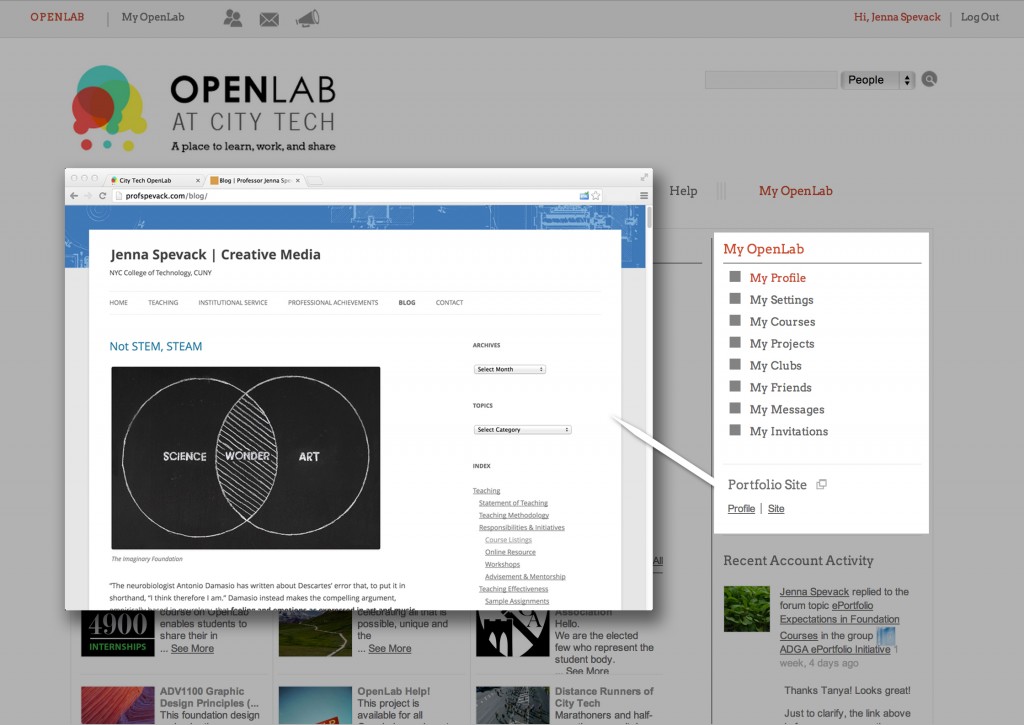

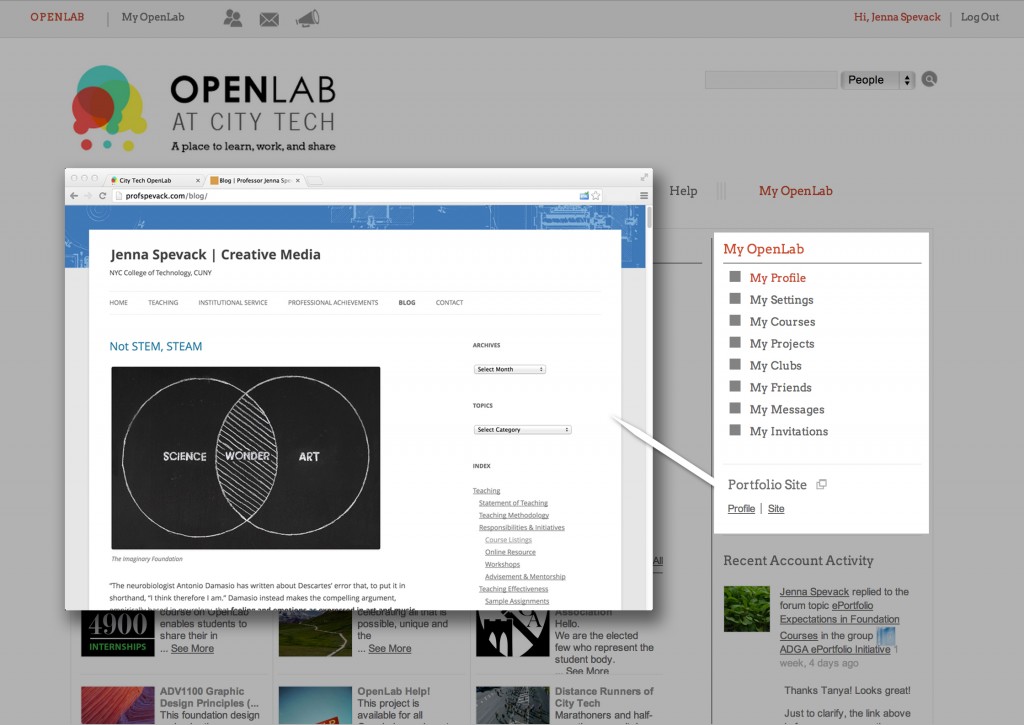

My OpenLab

In the early releases of the OpenLab, its navigation and usability needed significant enhancement. Members repeatedly requested easier access to their personal settings and dashboards. A simple name, My OpenLab, was adopted for the member’s logged-in state, which was identified in headings and dropdown menus. My OpenLab makes the member’s content more readily available and improves overall usability, but also conveys a sense of place and ownership.

Figure 5. My OpenLab navigation, Portfolio integration, external site linking

Figure 5. My OpenLab navigation, Portfolio integration, external site linking

External site linking

The ability to link a WordPress site to a group is available in BuddyPress, but this functionality did not extend to sites outside the OpenLab’s network. Many faculty members, some students, and a few campus clubs had however already developed web sites and were hesitant to start a site on the OpenLab if it meant recreating their sites there. Customizing the OpenLab’s BuddyPress install with the ability to link an external site to a group’s Profile now allows members with sites on other platforms to become part of the OpenLab community space, making this externally hosted content visible in activity feeds and on the home page. This seemingly small customization is actually a powerful intervention that simultaneously promotes member agency and inclusion. It allows the OpenLab to support those who are committed to maintaining a “domain of their own” (more formally, a “personal cyberinfrastructure,” Campbell 2009). We see this as particularly important for encouraging OpenLab participation among adjunct faculty, who may have their own independent teaching sites to accommodate their teaching on a number of campuses.

Cloning courses

As the number of courses on the OpenLab continued to grow, to over 600 current and past courses by the spring of 2014, it was clear that faculty needed tools to replicate their previous course structures, rather than starting from scratch. One key feature of the OpenLab is that course content remains available after the course ends; consequently, it was important to develop an alternative so faculty members would not empty courses for reuse by deleting past student data. This BuddyPress customization now offers faculty the opportunity to clone a course and establishes a best practice of maintaining an archive of past OpenLab courses available for student and department reference.

Portfolio integration

When the OpenLab was initially developed, the college was also looking for a new platform to host its student ePortfolios. The OpenLab was able to provide a home for this project, incorporating student ePortfolios into the site structure. A year later an initiative was launched to digitize faculty teaching portfolios and, once again, the OpenLab was the obvious place to turn. In response, we now offer all members of the college community the opportunity to create an online Portfolio, linked to the individual member’s Profile. Student ePortfolios, faculty teaching portfolios, and staff professional portfolios can now all be found together in the Portfolios section of the OpenLab. Through such design choices, the OpenLab becomes not only a solution to a logistical problem but a place for sharing, since students, faculty, and staff can see and learn from one another’s work.

These examples demonstrate our efforts to work toward a method of inclusionary innovation that encourages meaningful growth. We rely on member input to make the OpenLab the best it can be, with the aim of creating an inspiring, supportive gathering place that everyone at City Tech can share. The OpenLab’s designers strive to support this aim through compelling visual design that reflects well-considered information architecture and usability heuristics. Visitors and members alike regularly praise the OpenLab for its beautiful design. This is a tribute to the efforts not only of the current team but of the (now former) City Tech students who worked on the OpenLab’s original look and feel. Their design vision supports the hope that creating a beautiful place for learning, sharing, and belonging will foster community engagement and increase retention both within the OpenLab and at City Tech.

The OpenLab in Practice

Since the first semester of its use in beta, the OpenLab’s ambitious goals continue to be fulfilled in practice. The member-generated content of the OpenLab is a testament to the value of openness and of the laboratory model, and makes evident the OpenLab’s contribution to the college community. Examples of the benefits of the open, shared, democratic, and experimental avenues abound on the OpenLab.

Open

Charting new territory with a site on the OpenLab is a great opportunity for anyone interested in making content more visible. The OpenLab can offer a new and very real audience for that work because of its open nature. The openness of the platform encourages browsing through the shared materials, both in formal and informal ways—exemplified by a student who asked our Community Team why some courses were available for her to see whereas others required membership. She was following some of the courses in her major that she had not yet taken, or had taken with different professors, found reading these course sites a valuable resource, and began conversing with the faculty member to expand her education further.

Some courses assign what this student did voluntarily: to draw on the OpenLab’s openness as a source for learning. For example, a professor asked his Introduction to Poetry students to explore the OpenLab and to comment on materials on other courses’ sites. This not only challenged students to move beyond the comfort of their class’s community, but also reminded others that the OpenLab is open for this kind of cross-pollination. An English Composition professor asked students to examine other members’ avatars and report back about how they perceived members based on their avatars. This served the course as an introduction both to visual literacy and to the construction of an online persona. Another faculty member in Restorative Dentistry used the fact that the OpenLab is readily available to non-members by inviting colleagues from an international professional organization in the field of restorative dentistry to view his students’ work and comment on it. Here, students were exposed to an audience beyond the college, professionals with expertise to benefit their growth in the field.

Courses are not the only venues to benefit from being open. The needs of various college committees and organizations have been met by sharing information on the OpenLab. These additions have not been top-down, but rather reflect the community’s adoption of this much-needed place to collaborate. For instance, the college-wide Assessment Committee, in an effort to increase transparency and inform and involve more of the community, established an OpenLab Project that includes reports from the most recent assessment cycle for all participating departments. College Council has had a public site on a college server but is now developing its OpenLab presence. Committees that are open to all college faculty members might wonder what added value there could be in sharing their materials in the open forum of the OpenLab, rather than just with its voluntary members. In both of these examples, the openness of the site matters because the sites are part of the network, not hidden away from their potential audiences. Unlike stand-alone sites, the networked nature of OpenLab sites creates a broader audience for the work of these committees and organizations. Not only can faculty and staff members benefit from seeing what other committees are doing, but students as well can begin to see a clearer picture of the college, its infrastructure, and its concerns.

Shared

Community building is a central component of the OpenLab, creating venues for shared spaces in courses, among courses, and across the college. Learning Communities are a natural fit for the shared spaces of the OpenLab. These communities enroll a cohort of students in two or three courses that collaborate on a shared project or consider overlapping themes. In one of the first learning communities on the OpenLab, two professors in Hospitality Management and one in English connected their courses using the OpenLab via custom menus that seamlessly linked students from one course to the next. This connection fostered the sense that all three faculty members collaborated to create this more dynamic, more engaging experience for these first-year students. In another Learning Community, professors from Humanities and English similarly linked courses using custom menus in that first semester, and then subsequently began sharing their space in one Course site to facilitate their community’s joint project, a place-based endeavor that drew on semester-long projects that culminated in a virtual walking tour. This tour used various external technologies as it collated students’ on-site speech videos by embedding them in a shared Google map that was itself embedded on the shared OpenLab site.

The open nature of the platform can easily facilitate the development of unofficial learning communities. One instance came when two math professors joined efforts when each taught a section of the same course in the same time slot. They shared one OpenLab site for students to exchange reflections on their joint field trip, a walk across the Brooklyn Bridge to provide the basis for mathematical calculations, and even booked a larger classroom for one class session to accommodate both classes in a discussion of the results from their joint field trip. Other faculty members have experimented with unofficial learning communities, such as one bringing together a hybrid section with a fully online section of the same course. The opportunity to communicate and collaborate with other students is so important for the otherwise disconnected online students; pairing them with students who do have the chance to get to know each other face-to-face enhances the learning experience overall among the members of the created community.

Experimental

With the capability to expand educational opportunities through incorporating multimedia components into posts and pages, the OpenLab fosters the hands-on, active learning so many in our community strive to integrate into their courses. The availability of spaces to contribute content in a variety of media on the OpenLab can inspire disciplines not traditionally thought of as visual to make use of the site’s capability to incorporate images and videos, or those not typically considered writing-intensive to include expository blog-posts or collaborative-document assignments. In one math course on the OpenLab, students were asked to reflect on the term infinity both in its colloquial usage and as a mathematical term. To further support their understanding of these definitions, students were asked to relay a story about when they first learned about the term, and to incorporate a photograph that encapsulated the meaning. Writing, visual literacy, and a sense of play became vital skills to complete this math assignment, a great example of how the OpenLab creates a place for creative expression and innovative pedagogy.

In an Introduction to Hospitality Management course, students were asked to consider Brooklyn as the site of tourism. Imagining they were each the concierge in a boutique hotel in Brooklyn, students were asked to develop videos that guests would watch to pique their interest in a nearby location. Students could creatively cast their videos, considering not only the details of a location, but also the intended audience of the video and how they would want to represent the location to the clientele. This project took advantage of YouTube as a resource for storing videos that were then easily embedded into posts. It also identified for students their role and their audience, and offered a creative medium for students to consider the role of the concierge, and to experiment with place-based learning in a field-specific way.

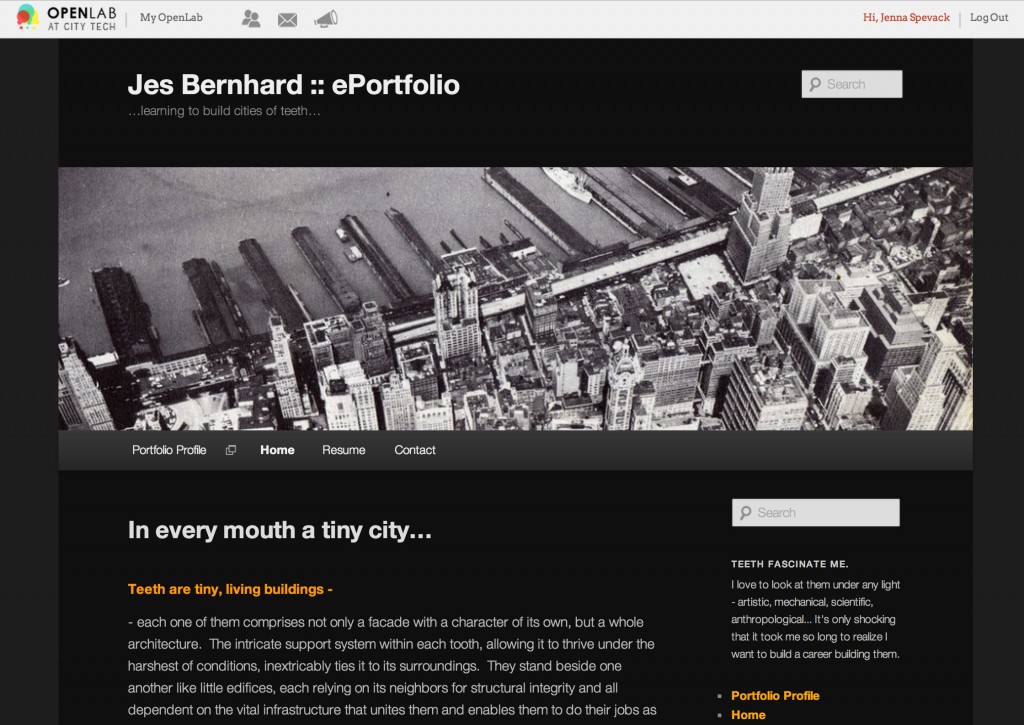

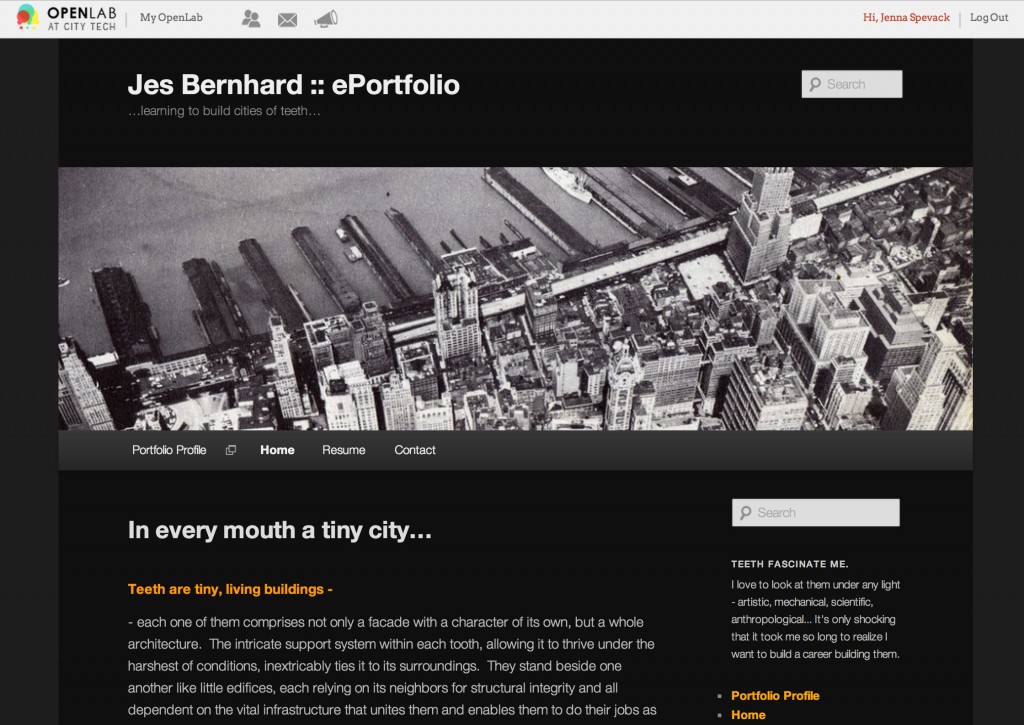

In each of these examples, students had opportunities to use openly available digital tools and to transfer knowledge and skills from their college experience to work in their disciplines. Faculty members could continue to cover course content while expanding their pedagogical practices and affording students additional avenues for experimentation and creative expression. One student took on this challenge independently, conceiving of her ePortfolio not merely as a way to record her achievements in Restorative Dentistry but also as a customizable, thoughtful reflection of her approach to her field. Using the extended metaphor of a city to describe the mouth full of teeth, she showcased her dedication to her work and her interest in experimenting both in the lab and in her representation of that work.

Figure 6. Student ePortfolio: Restorative Dentistry

Figure 6. Student ePortfolio: Restorative Dentistry

Democratic

All members have the ability to create Projects, Clubs, and Portfolios—only faculty can create Courses, which is the only difference in permissions among the types of members—and to read or actively participate on public sites throughout the OpenLab. This means that in addition to officially sanctioned committees and clubs, there are numerous unofficial, unchartered, or even previously unformed groups coalescing in OpenLab Projects and Clubs. In a recent survey of OpenLab Clubs, the Community Team found that more were unchartered than officially City Tech-sanctioned, indicating that the OpenLab has given a place for students—and all members—to gather around common interests regardless of official support. Thus, in addition to the notable presence of the Student Government Association and the City Tech newspaper, there are also unchartered clubs such as Anime Gaming Underground, or the Mobile Application Developers. We are eager to provide support—both technical and community-building—for these ventures to become fully realized.

Projects such as the First Year Writing and Developmental Writing Resource Archive, which offer resources for faculty teaching the college’s sequence of composition courses and developmental writing, respectively, encourage full-time and adjunct faculty to join, share, and benefit from the wealth of resources that have been compiled. Providing opportunities for full-time and adjunct faculty members to share space and resources has been one of our main goals for the OpenLab, making it a space for all to get involved, regardless of rank or position. Many new projects are being developed to collate materials for faculty working on a given course or initiative, and to share discussion space to collaborate on the issues at the heart of that endeavor. These spaces open the conversation to adjunct faculty, creating avenues for their involvement that have not existed before. OpenLab workshops also create such shared spaces, since they provide support for faculty and staff, full-time and part-time alike, and can facilitate collaboration across and among departments and offices. As part of the Title V grant, adjunct faculty members receive a stipend to participate in OpenLab workshops; this further facilitates their inclusion in the OpenLab.

The OpenLab in Progress

These are just a few examples of the kind of work that the OpenLab enables; every day visitors to the site can find more. It has been exciting to see how the OpenLab’s members have grasped its potential for connection and collaboration, openness, sharing, and community-building. But of course technologies do not determine outcomes. Indeed, as Gold and Otte note in their discussion of the CUNY Academic Commons, any intervention in the mode and means of social interaction—and perhaps especially in education—is potentially disruptive and destabilizing (Gold and Otte 2010, 10). Inevitably, then, with all the OpenLab’s successes, there have been challenges along the way. Below are three of these and the approaches taken to address them.

Growing pains, growing community

The first challenge has actually been the OpenLab’s success: its dramatic rate of adoption. As the Living Lab’s external evaluator noted, the project’s original usage target (1,000 active members by the end of the grant) quickly looked “quaint.” Such vertiginous growth naturally brought technical concerns: with the site rapidly becoming essential to many of its members, we hardened its infrastructure for reliability and have recently optimized the database to ensure it can support this rate of growth for years to come. The biggest impact, though, has been experiential—a site with thousands of members simply feels different, and the individual members and the work they create can easily be lost in the sheer volume of activity and content. If we fail to attend to the affective dimension of site use, we could find ourselves simply replicating online the problems of disconnection and fragmentation that the OpenLab hopes to address.

Early in the development process, we made adjustments to the site design to showcase member content more effectively and make it more readily findable: the home page now shows the four most recently active groups of each type (Courses, Projects, Clubs, and Portfolios), and search and filtering capabilities have been added. Another important addition to the home page is the “In the Spotlight” section, which allows us to call attention to a different example of the exceptional work on the OpenLab each week. Members have reported their excitement at having their work recognized so prominently; when we featured the Restorative Dentistry student’s ePortfolio described above, its author responded that this appreciation of her work had not only provided encouragement but also “made it something real” for her, “something that a living person actually looked at and read (as opposed to an odd exercise similar to jotting things down, folding them into paper airplanes, and launching them into the cybervoid)” (Jes Bernhard, pers. comm.). We are planning other ways to celebrate member contributions and enable all members to participate in the selection process.

Evident in the above is the interplay between software and social. A social network should not be conflated with community;[5] building a sense of community among OpenLab members is an ongoing process that requires conscious and intentional individual and collective effort. The Community Team plays an important role here in helping members feel welcome on the site. With such a large member population, though, the Community Team cannot interact with everyone—members must create community by and for themselves. And they are. Many members complete public profiles and make “friend” connections. New faculty have set up a private space where they can share their experiences, ask questions, and discuss concerns. Faculty members continue to use the OpenLab to share ideas and resources, and discuss best practices with colleagues; adjunct faculty, who often find themselves marginalized at their institutions, are joining these conversations. Important student-facing administrative offices—Veterans Affairs, for instance—see the OpenLab’s potential for giving the students they serve a space of their own to communicate. Students have created initial presences on the site for key organizations and informal interest groups, too.

We believe, though, that there is more we can do to foster community on the site. We will be working to understand, through quantitative and qualitative approaches, how the OpenLab’s members (especially its less vocal members) use and experience the site, what works and does not work for them. We will be creating ways to bring members together on the OpenLab for shared activities—including, simply, fun.

A place for students

We are particularly interested in understanding the perspectives of one key group: students. Students make up the majority of OpenLab members (over 90% at this writing). However, despite the success of Courses on the OpenLab, the wide array of individual and group Projects created by students for their coursework, and strong adoption of student ePortfolios, we have yet to see widespread adoption of the site for extracurricular activities. There are many external factors that undoubtedly influence student use of the OpenLab. In addition to the time and space constraints we know affect City Tech students, another factor that may have an impact on their voluntary use of the OpenLab is access to technology. Although many own or have access to their own computers, tablets, or smartphones and Internet access from off-campus, others do not, and must rely on shared computers in their homes or at the college. As enrollment has risen, campus computer labs, like the campus overall, strain to accommodate the increasing number of students who wish to use them (Smale and Regalado, 2011). Thus, students may not always be able to access the OpenLab at a time and location that is convenient for them and conducive to using the OpenLab for extracurricular reasons. Additionally, while there are convincing arguments for using the OpenLab rather than closed, proprietary platforms, students may see Facebook or other social networks as more appropriate for co-curricular and extracurricular activities since they already socialize there.

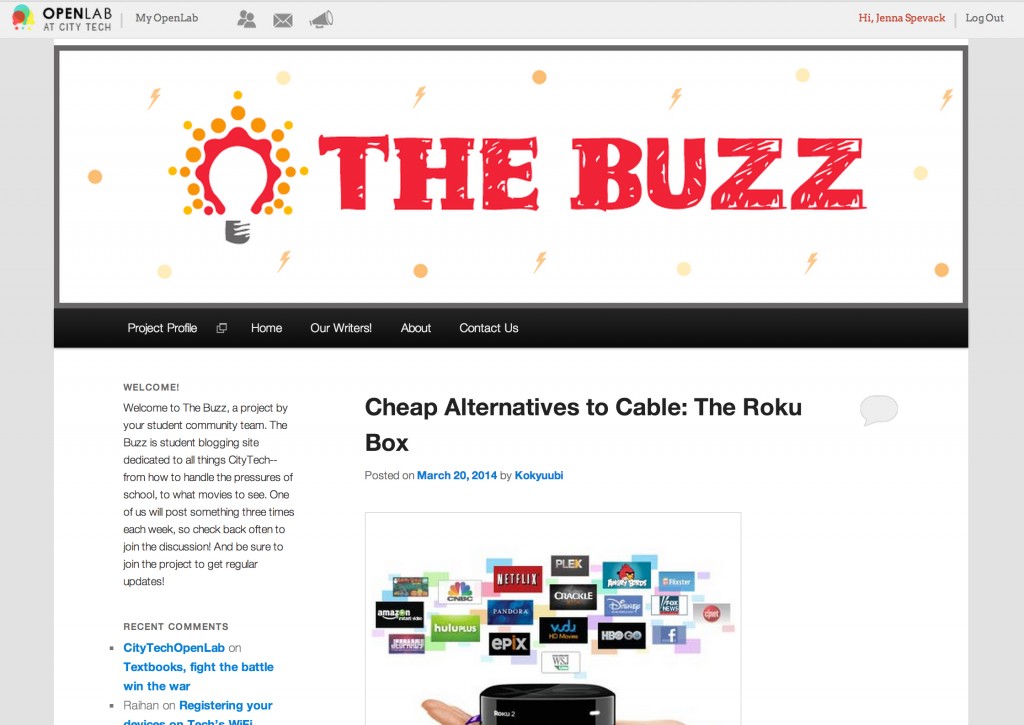

We have no desire to construct a “creepy treehouse” to lure in students (see Gold 2011 for a discussion of this term [73-4]), but are concerned to help them understand that the OpenLab enables them to create places of their own, and that they can be co-creators of the OpenLab itself by participating in our collaborative development process. In response, we are making concerted efforts to engage City Tech’s students beyond the classroom. We have recently recruited a group of Student Community Team members who contribute regularly to a site they have named “The Buzz,” and are looking to expand the team to continue to provide dynamic content by and for our student population. Student team members have also begun working with our Community Team to conduct proactive outreach to student clubs and other organizations and provide them with help and guidance on incorporating the OpenLab into their activities. We hope that these efforts will encourage deeper integration of the OpenLab into student life at City Tech.

Figure 7. Student Community Team Blog “The Buzz.”

Figure 7. Student Community Team Blog “The Buzz.”

Understanding the OpenLab

We are deeply committed to the OpenLab as a democratic space where students, full-time and adjunct faculty, and staff are equally welcome and valued, a space that they own and which is shaped by their needs, that encourages openness, connection, and experimentation while respecting its members’ privacy and their right to share, hide, create, or delete their work as they see fit. We have found, however, that conveying this vision requires continued work. Although many members have been with us for months or even years, each semester brings new students and faculty to City Tech and new members to the OpenLab. This means that, just as we explain the site’s features and functionality to new members, we must also seek to convey the aims and ethos of the project. Some members regard the site as another Blackboard or Facebook and complain that its features are lacking in comparison. We explain that their missions could not be more different—that Blackboard is a learning management system primarily focused on courses whereas the OpenLab is a space that anyone at City Tech can use (and that the platforms can readily co-exist). In regards to Facebook, we might observe that our efforts to build a social network at City Tech are ultimately aimed at improving student outcomes, not monetizing their data.

Members can certainly use the OpenLab without knowing or perhaps even endorsing its underlying argument. Accustomed to working with closed, rigid, and proprietary products over which they have little control, many people are not likely to expect educational and social media software to be open, flexible, and dedicated to enhancing their agency. We have learned, though, that the lack of a shared understanding of the project can limit its potential. For instance, if faculty members do not know the pedagogic benefits of the OpenLab’s open and collaborative features, they are less likely to use them; students will be reluctant to provide feedback if they have no expectation that their concerns will be heard and acted on; adjunct faculty may not join an open interest group if it is unclear that it is truly open to all.

Finding effective ways to build this shared understanding, then, is critical to our outreach activities. We have created a brainstorming game that faculty members can use to generate assignments that employ the affordances of open platforms such as the OpenLab to support specific learning objectives. This game has been used for City Tech professional development, and we have run interactive sessions at conferences to further promote open digital pedagogical practices. We are continuing to enhance the OpenLab’s Help content, and we have established an Open Pedagogy Project as a place to discuss and share best practice examples of OpenLab usage—explicitly articulating the project’s goals and guiding principles in spaces such as this allows us to hone them and debate them with the OpenLab’s members, and challenges us all to live up to them.

Sharing the OpenLab: at City Tech and with you

Each new semester allows us to revisit, revise, and improve. Not only our development approach but our entire project process is iterative, so the next few years promise to be as eventful as the last. We will continue to evolve the OpenLab in response to member feedback. A generative platform generates ideas; members are constantly coming up with new ways to use the site. One recent and exciting request is to provide support for alumni mentoring of current students. Additionally, the student team has come up with important suggestions that could help build community on the site, such as highlighting members with similar interests and mutual friends. Finally, like any active development project, we have a laundry list of improvements, large and small, that would benefit the OpenLab’s members.

Key for the project’s relationship with the college is the idea that members can work with the OpenLab, not just on the OpenLab. In other words, an open platform, built by and for City Tech, offers opportunities for collaboration, participation, and co-creation that are unthinkable with closed, proprietary software solutions. For example, the OpenLab creates rich possibilities for curricular integration across a wide range of disciplines. We have already developed an internship program in partnership with our consulting developers and City Tech’s Advertising Design and Graphic Arts department that has given students real-world experience in documenting and enhancing the OpenLab. We can imagine other synergies: students in City Tech’s new professional and technical writing major could create Help content that would be read by thousands of people; classes in web development could create plugins for the OpenLab and thus for the BuddyPress and WordPress communities; students in education fields could analyze and learn from best practices they find on the site. Thus, in addition to reaching out to student organizations, we are also working with academic and administrative departments, other grant-funded projects, committees, and so on, to help them explore what the OpenLab can mean for their work.

Looking beyond City Tech, we are also committed to sharing both what we have built and what we have learned along the way in creating, using, supporting, and sustaining the OpenLab. We have begun that process here, and welcome questions and comments. We have identified discrete items of OpenLab functionality that can be packaged as software plugins for release within the scope of the current grant funding. Our plans for future development include contributions that will benefit the wider WordPress and BuddyPress communities. Most excitingly, we are seeking to partner with others to make the OpenLab’s key features—such as, for instance, our customizations of BuddyPress group functionality—freely available to all.

The OpenLab has joined other dynamic initiatives in offering members opportunities for opening education. With the strength of this experience behind us, we close with a challenge. Free and open source software is proven, robust, and sustainable. A community of practice freely shares recommendations and advice, and the OpenLab team benefits from and seeks to give back to this growing and generous group. Every day the OpenLab provides a living demonstration of what students, faculty, and staff can achieve with an open platform that is built for community. Members across the college have seized the opportunities that the OpenLab provides to create open and shared spaces, to experiment and innovate, and have provided innumerable examples of the benefits of using and contributing to an open platform. We ask readers, and visitors to the OpenLab, to imagine what the use of open digital tools can do to strengthen their communities. The tools to open education are already at hand.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all members of the OpenLab team, present and past, for their contributions to the project. We are grateful to the OpenLab’s many supporters at City Tech, including all our colleagues in the Living Lab initiative. Finally, our deepest thanks go to the OpenLab’s members—without whom, of course, the site would be an empty shell. The OpenLab is enabled by “A Living Laboratory: Revitalizing General Education for a 21st-Century College of Technology” (2010-2015), a $3.1 million project funded by the U. S. Department of Education under its Strengthening Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSI) Title V Program.

Bibliography

Campbell, Gardner. 2009. “A Personal Cyberinfrastructure.” EDUCAUSE Review 44 (5): 58-9. Accessed October 20, 2013, http://www.educause.edu/ero/article/personal-cyberinfrastructure. OCLC 42937303.

CUNY Office of Institutional Research. 2012. “2012 Student Experience Survey.” Accessed October 20, 2013, http://www.cuny.edu/about/administration/offices/ira/ir/surveys/student/SES2010FinalReport.pdf.

Gold, Matthew K. 2011. “Beyond Friending: BuddyPress and the Social, Networked, Open-Source Classroom.” In Learning Through Digital Media Experiments in Technology and Pedagogy, edited by R. Trebor Scholtz, 69–77. New York: Institute for Distributed Creativity. Accessed October 20, 2013, http://learningthroughdigitalmedia.net/beyond-friending-buddypress-and-the-social-networked-open-source-classroom.

Gold, Matthew, and George Otte. 2011. “The CUNY Academic Commons: Fostering Faculty Use of the Social Web.” On the Horizon 19 (1): 24–32. OCLC 39502849.

Gorges, Boone B. 2012. “Sowing the Seeds.” Teleogistic. Accessed October 20, 2013, http://teleogistic.net/2012/03/sowing-the-seeds/.

Kinzie, Jillian, Robert Gonyea, Rick Shoup, and George D. Kuh. 2008. “Promoting Persistence and Success of Underrepresented Students: Lessons for Teaching and Learning.” New Directions for Teaching and Learning (115): 21–38. OCLC 6541567.

Krause, Kerri-Lee D. 2007. “Social Involvement and Commuter Students: The First-Year Student Voice.” Journal of The First-Year Experience & Students in Transition 19 (1): 27–45. OCLC 40245359.

Kuh, George D., Jillian Kinzie, Jennifer A. Buckley, Brian K. Bridges, and John C. Hayek. 2007. Piecing Together the Student Success Puzzle: Research, Propositions, and Recommendations. ASHE Higher Education Report v. 32, no. 5. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. OCLC 123013011.

National Survey of Student Engagement. 2012. “Promoting Student Learning and Institutional Improvement: Lessons from NSSE at 13”. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research. Accessed October 20, 2013, http://nsse.iub.edu/html/annual_results.cfm.

New York City College of Technology. n.d.a. “About City Tech: Consumer Information.” Accessed October 20, 2013, http://www.citytech.cuny.edu/aboutus/consumer_info.shtml.

———. n.d.b. “About City Tech: Heritage & History.” Accessed October 20, 2013, http://www.citytech.cuny.edu/aboutus/heritage_history.shtml.

———. 2012. “Facts 2012-2013.” Accessed October 20, 2013, http://www.citytech.cuny.edu/files/aboutus/facts.pdf.

Smale, Maura A., and Mariana Regalado. 2011. “‘Sometimes I Type Papers on My Cell Phone:’ Mobile Digital Technologies and CUNY Students.” Paper presented at MobilityShifts: An International Future of Learning Summit, The New School, New York, New York, October 10-16. Accessed October 20, 2013, https://ushep.commons.gc.cuny.edu/results/.

[1]The OpenLab is the work of many hands, as will be evident here and the Credits page shows. The “we” used in this article thus seeks to represent not only the authors but the entire OpenLab team.

[2]The Living Lab includes three activities in addition to the creation of the OpenLab: conducting a faculty development seminar focused on using place-based learning and high-impact educational practices to infuse general education into courses; integrating the assessment of general education student learning outcomes across the curriculum; and building an endowment for the Brooklyn Waterfront Research Center. More information is available on the Living Lab project site.

[3]A valid City Tech email account is required to register with the site. Members retain access to their accounts during periods of inactivity and even after leaving City Tech; we believe members should have agency in controlling the content they have created on the site.

[4]Note that the Community Team concept is borrowed from the CUNY Academic Commons. We also benefit from the OpenLab’s other sibling installations in that our team members gained their experience by working with several of these initiatives. Additional support for students and ePortfolios is provided by the college’s Student Help Desk and ePortfolio teams.

[5] Boone Gorges, one of the lead developers of BuddyPress and a member of our team, has also made this observation (2012).

About the Authors

Charlie Edwards is Program Manager of the “Living Laboratory” initiative at NYC College of Technology, CUNY. After twenty years in commercial IT, she is now also a graduate student in the English PhD and Interactive Technology & Pedagogy Certificate programs at The Graduate Center, CUNY, with research interests in the Digital Humanities and Victorian popular fiction. She can be reached at cedwards@citytech.cuny.edu.

Jody Rosen is an Assistant Professor of English and OpenLab Co-Director at NYC College of Technology, CUNY. Her research focuses on communication-intensive instructional practices in the classroom and in professional development, as well as representations of gender and sexuality in early twentieth century Anglo-American literature. She can be reached at jrrosen@citytech.cuny.edu.

Maura Smale is Associate Professor/Coordinator of Library Instruction and OpenLab Institutionalization Lead at NYC College of Technology, CUNY. Her research interests include undergraduate academic culture, game-based learning, open access publishing, and critical information literacy. She can be reached at msmale@citytech.cuny.edu.

Jenna Spevack is Associate Professor of Creative Media and OpenLab Co-Director at NYC College of Technology, CUNY. As an artist, designer, and educator, her projects and practices explore how interactions with and connections to ecological systems support resilience in the shifting natural-social-political landscapes. She can be reached at jspevack@citytech.cuny.edu.