Introduction

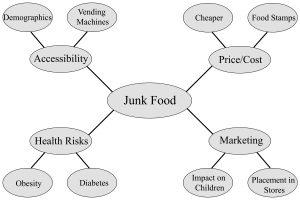

Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR) technologies are becoming more prevalent in educational settings. AR and VR have been used to facilitate and enhance students’ learning in almost all disciplines, including but not limited to science, engineering, medicine, psychology, and the humanities. For example, augmented reality games have been used to create a sense of authenticity in medical training (Rosenbaum, Klopfer, and Perry 2007). The use of AR and VR in the classroom instruction has shown positive impact on increasing motivation and improving students learning outcomes for specific tasks (Di Serio, Ibáñez, and Kloos 2013, Sharma, Agada, and Ruffin 2013). One such example of a pedagogical benefit and affordance of mixed realities is the capacity to resize or manipulate objects that would be too small or too large to study in a traditional setting. Other examples include the ability to integrate and overlay contextual information alongside visual cues. AR, VR, and archival resources support pedagogical models including constructivist learning, inquiry-based learning and game-based education. Given these factors, there is potential to explore AR and VR technologies as ideal conduits for enhancing student engagement within instructional programs of library archives and special collections.

Professionals in museums and other cultural heritage institutions employ these technologies to enhance their user experience with collections. Relevant examples from these allied fields explore the basis of coupling AR and VR with archival resources to democratize instruction and outreach programs. Preservation and security concerns confine the physical manifestations of archival materials to onsite, proctored reading rooms. Archival programs, when able, offer access to digitized, born-analog records to increase discovery and use, as well as protect materials from exposure to elements that speed deterioration. When presented online, both born-digital and analog archival materials may appear static, rigid, and unable to entice contemporary learners. AR and VR not only improve access to archival materials by reducing physical proximity and capability barriers to access, but also aid in the preservation of fragile materials. AR and VR technologies enhance the archival instruction experience beyond current practices of digital presentation. Curating an interactive environment with these technologies provides contextual meaning and additional information that is important to engage students during instruction and outreach initiatives. With AR and VR technologies, instructional experience outside of the archival reading room more closely mirrors the serendipitous, real-life encounters with archival resources.

Despite being mentioned together, AR and VR are different technologies and bring distinct possibilities to instruction and outreach with archival resources. As defined by Ronald Azuma (1997), AR integrates virtual and physical information, interacts with the environment in real time, and the content is displayed in three dimensions. VR, on the other hand, typically creates a virtual scene or recreates reality in a virtual environment to offer an immersive experience. At the Georgia Institute of Technology, a STEM-focused public university, librarians and archivists are exploring the potential for using AR and VR technologies to enhance outreach experiences and facilitate educational engagement with Georgia Tech archival materials. This article discusses the potential of employing these technological tools to help improve instruction and students’ engagement with Georgia Tech’s special collections.

New Pedagogies and Methods of Student Engagement at the Georgia Tech Library

The Computational Media program at Georgia Tech is a collaborative effort by the College of Computing and the School of Literature, Media, and Communication (LMC). Students in this program specialize in areas including interactive game design, human-computer interaction, digital arts, media theory, media history, and software design. One component of this program is providing students with an opportunity to focus on their research interests in an internship-style setting mentored by Georgia Tech faculty. Through these research-for-credit course sections, students are presented with a real technology-based challenge from a campus department. The students are given a semester or two to first research the issue and then prototype potential solutions. Student findings are summarized in a report or presentation that is assessed and graded by mentoring faculty. In many cases the students’ findings or outputs are incorporated into the departmental workflow and lead to new use cases, models of service, or further research.

The Georgia Tech Special Collections and Archives have a robust teaching and outreach program. Each year more than two thousand faculty, staff, and students use the archival resources to develop lesson plans, fulfill mission critical duties, and complete course assignments. Most of the archival materials are stored in an offsite storage facility, which provides a high-capacity, state-of-the-art space with ideal climate conditions but stifles on-demand access to most of the collections. Recall from the offsite facility can take up to forty-eight hours. By implementing AR and VR technologies with archival resources, users receive immediate access to the information they need.

In recent years, Georgia Tech librarians and archivists have been serving as mentors for students participating in these research sections. In the fall of 2017 and spring of 2018, one of these special topic courses had students working with the Georgia Tech Library Instruction program and the Data Visualization Lab on how VR could be used for teaching and learning. This class was designed to be exploratory and self-directed, presenting students with fairly broad learning objectives. Outside of having the basic framework for a small educational game built, the main learning objective of the class was for the students to be able to identify the main components of the VR design and development lifecycle through hands-on experience. Additionally, the cohort was to produce a report that included a directory of campus resources and tools necessary for these types of projects. Finally, they were to explain how someone using VR for educational purposes might assess the effectiveness of these methods.

This small group of students began analyzing how VR technologies could be used to showcase, enhance, and engage other undergraduates with the library’s special collections. Students were challenged to use immersive technologies to address the issue of accessibility for these unique resources. Approaching these issues through the lens of storytelling and experiential learning, the student team first conceptualized the narrative for an educational game that would introduce other students to items within Georgia Tech’s archival collection.

The class project was initially designed to be a component of the first-year experience program on campus. First year students would be introduced to library resources in a virtual setting and quizzed on these concepts through interaction with an avatar. After storyboarding their initial ideas, the students began with an environmental scan of campus resources, partners, and technologies necessary for completion of the project.

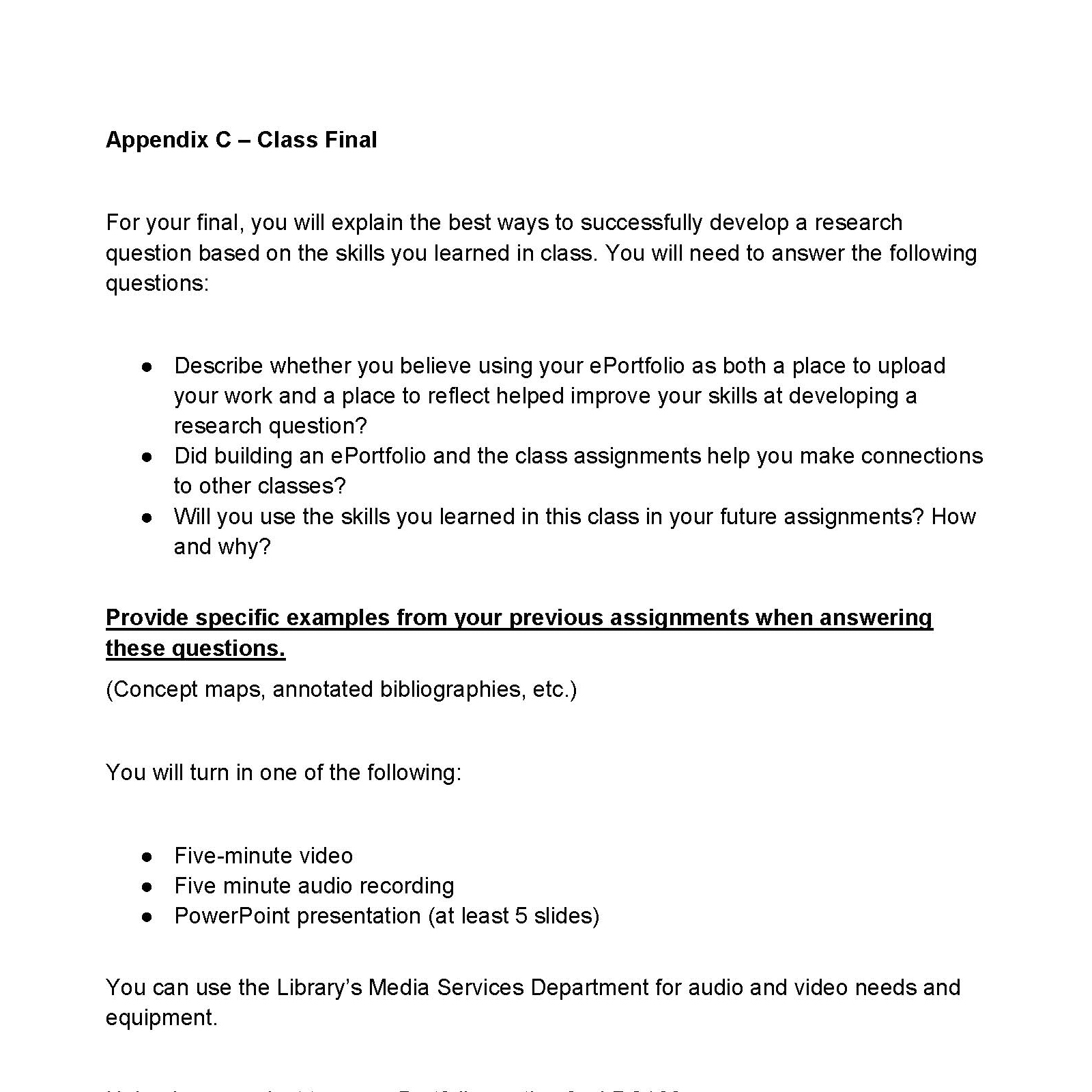

The cohort explored the campus invention studio and tools used for 3D scanning. The Artec Spider 3D scanner was the primary tool used for capturing three-dimensional images of artifacts from Georgia Tech’s special collections. This scanning process creates a three-dimensional representation of an object that can then be imported into Unity, a cross-platform game engine the class used for developing 3D content and compiling all contents to a VR game. Therefore, the scanning process was one of the first phases in the students’ project development. The three-dimensional scanning process alone was a major challenge. The 3D scanning process presented enough hurdles and issues for an entire semester’s worth of analysis and research.

Figure 1. Student using Artec 3D scanner in engineering lab to scan football helmet from Georgia Tech Archives

One problem facing the students was how to handle scanning complex textures and managing surface variations of the artifacts. Dark or shiny objects proved to be particularly time-consuming and problematic. For example, the students had hoped to use the archive’s prototype of the 1996 Olympic torch in their educational game but were not able to capture the texture information in a 3D scan. In some cases, objects can be greased with a developer spray which prepares the surface and creates an ideal environment for scanning, thus decreasing distortion. However, when it comes to working with rare or delicate artifacts such as the torch, these solutions are not an option. In hindsight, the librarians guiding the project determined that the 3D scanning process could and should have been a solo research project. Future iterations of this class will distill the research focus of the class into manageable components that can be built upon, combined, and eventually grown into a larger scope project over multiple semesters.

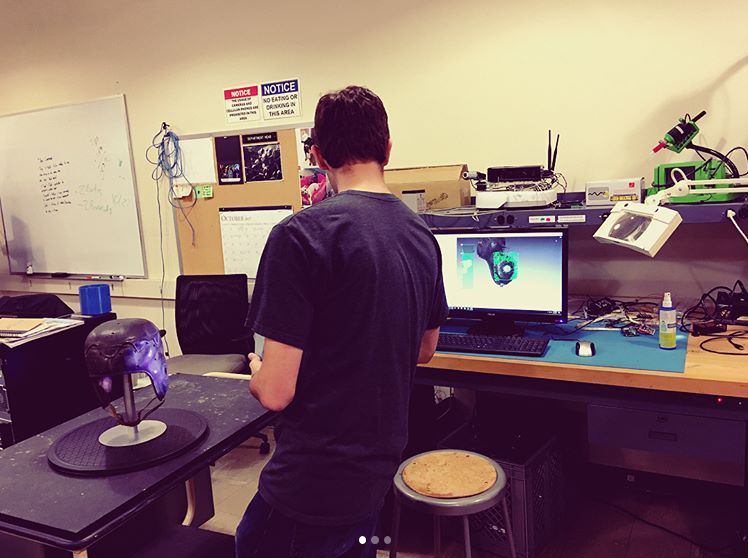

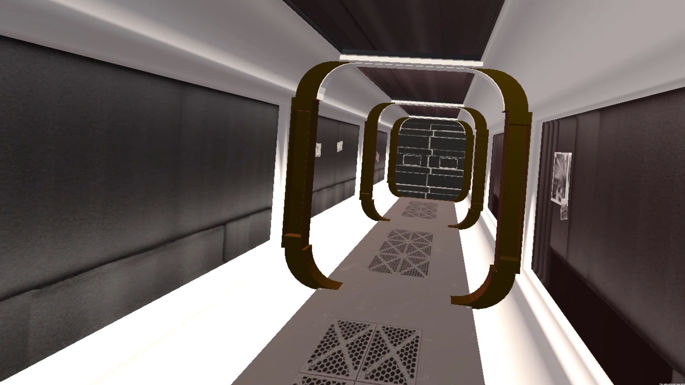

Given the large scope of the topic presented, students later modified their project design to function more as an interactive campus tour that included scanned photos of campus landmarks and some historical imagery from the library archives. This late stage modification was largely a result of the issues they encountered during the 3D scanning process. The 3D scanning and subsequent attempts to import the scanned objects into the development engine Unity proved to be extremely difficult. In an attempt to narrow the focus of their project, the students collectively changed the narrative of the game allowing them to use assets, such as the photographs, that were technologically easier to work with. The substitution of photographs instead of 3D scanned objects allowed the students to focus more of the development process as a whole rather than getting hung up on isolated yet critical problems that would prevent completion of the project.

Figure 5. Hallway in Georgia Tech Space Station Game showing images from the Georgia Tech Archives hanging on the wall, detail below.

Figure 6. 2D scanned archival images hanging on the hallway wall inside of Georgia Tech Space Station Game

The Georgia Tech Library’s role in these for-credit research classes presents a new pedagogical model where librarians and archivists drive the research on campus by taking an active partnering and mentoring role in student research. A year of working with the students in this capacity has informed how we approach the role of an academic library and the services provided. Redesigning traditional service points in a cutting-edge way highlights the mission of the Library NEXT project (http://librarynext.gatech.edu), which is looking to reevaluate and chart the course of the library’s place in the twenty-first century world. Library NEXT is not only a physical transformation and renovation of the Georgia Tech Library, but it is also a reimagining and reinvention of our library services. A large part of Library NEXT is making services more visible. A new data visualization lab, classrooms, and exhibit spaces in the renovated library highlight data modeling, educational programs, and archival services providing more transparent access. Virtual reality and multimedia labs in libraries are not uncommon on college campuses, but they are often self-directed or self-serve spaces without librarian and archivist led research or learning initiatives (Oliveira 2017, Moore et al. 2018). Georgia Tech Library faculty and staff are striving to break down these independent silos and passive spaces. This model also presents an opportunity for novel partnerships and collaboration between librarians, archivists, and technology specialists; each brings expertise to the endeavor and all work together to highlight and utilize special collections and resources while engaging our community.

Archivists work with a variety of campus partners to engage local community groups through outreach initiatives. Two times a year, the Georgia Tech Community Development Office hosts primary students from local school districts during a “Tech Discovery Day.” The archivists created sleuthing centers for visiting middle-school students to discover the history of Georgia Tech and have hands-on experience with primary source materials. The event was held in a building separate from the archives department. Had there been rain, the demonstration would have been canceled. The need to protect the rare and unique records from harm or deterioration supersedes any individual experience. Placing this demonstration in an AR or VR simulation will free the materials from the constraints of mother nature. For this particular audience, the digital simulations may also spark interest in “old stuff” presented in a novel fashion.

Video Player

The Educational Landscape of VR and AR in Archival and Allied Fields

VR and AR as Access Tools

AR and VR technologies have their respective advantages and disadvantages. VR is not attached to the actual artifacts or environments, which allows VR projects to be taken off-site as the hardware permits. However, current high-end VR devices demand specific set up configurations. Major VR devices in this category like Oculus Rift, HTC VIVE, and upcoming HTC VIVE Pro require costly gaming PC to drive high-quality graphic rendering. They also come with tethered heavy headsets and powered sensors as part of the device package. There have been portable mobile VR devices, such as Google Daydream VR, Google cardboard, and Samsung Gear VR, that enable phone VR experience if the graphic quality and room scaling are not the focus of the design. The upcoming Oculus Go sits between these two categories. Different options of VR devices open up opportunities to a variety of archival instructional designs.

AR design, on the other hand, relies on and interacts with the local environments to function. Because of this criteria, some archives-related AR projects only function in close proximity to the archival materials or environments with embedded trigger information, like GIS information or QR codes. AR enhances user experience through interacting with the physical environments. The advantage of AR for archives projects is that the hardware is easy to access, most times requiring only a smartphone, and that layers of information, including text, image, audio, video, 3D scanning, as well as virtual prototype, could be projected on physical objects to enrich and expand the learning experience. When it comes to application in archival materials, it is important to keep in mind these pros and cons to help make design decisions.

The potential for teaching and outreach with archival materials using AR and VR technologies is vast but requires collaboration with partners outside of the field. Tonia Sutherland suggests that “collaborating with scholars in fields such as the digital humanities and embracing new media technologies…create new possibilities for archivists to capture and preserve performance and other traditions, practices, and events” (2016, 393). A variety of AR and VR-facilitated projects have been done in archives-like environments, primarily at museums and cultural heritage sites for educational purposes. The projects detailed below serve as inspiration for the use of these technologies and applications in an archival setting.

Instruction with archival resources lends itself to hands on teaching pedagogies like constructivism and inquiry-based learning. Silvia Vong notes “special collections and archives have great potential to nurture students’ curiosity. Therefore, the use of a learning framework in that environment could transform it from just a physical space that houses books, papers, and objects to a place filled with discussion and interaction between students and teachers” (2016, 150). VR and AR technologies explore further the applications of these frameworks in advancing pedagogies of archival instruction by making the documents and artifacts relate to one another in a way that mirrors contemporary searching styles and information presentation.

Developing VR environments and AR tools to help instruct with archival materials entices students to reconsider the relevance of past events to current issues. Barbara Rockenbach writes “…students should be exposed to a learning environment in which they ‘deal with topics that will stimulate and open intellectual horizons and allow for opportunities for learning by inquiry in a collaborative environment” (2011, 299). The multidisciplinary nature of VR and AR projects using archival materials necessitates an environment where people with different skill sets work towards an end goal. Instructional faculty are also key stakeholders in this scenario. Again, Rockenbach recommends that “[i]nstead of contacting professors with a plan that sounds overly programmatic (a mistake made by librarians trying to shoehorn faculty needs into the strictures of the Information Literacy Competency Standards), we’ve had some success…by listening to faculty and trying to understand their specific objectives and suggesting some creative collaborations based on learning theory” (2011, 302). VR and AR systems using archival materials have a variety of lesson plan and learning objective crosswalks that can increase the usability of the archives by a broad audience.

Technology Applications

In the archival context, the use of new media technologies is a dream hoped for by many but obtained by only a few. Depending on size, budget, and distinction, archival repositories provide inconsistent virtual access to materials. Online descriptions of archival collections displayed by electronic finding aids give minimal awareness of archival content. A more robust digital presence displays actual archival materials at the item level (ie a letter, a photograph, or a map). This access is achieved through digitization projects or links to born-digital records. The potential of AR and VR technologies to create interactive digital experiences lies partly in its ability to empower students and teachers to access and use archival records. Duff and Haskel note that “[a]rchives need to embrace archival 2.0 programs that extend archival access and facilitate open-ended conversations with their communities if archival records are to be exposed to new contexts and new uses” (2015, 42). Archival institutions have been employing mobile apps, social media crowdsourcing, GIS interactives, and gamification projects to reach out to users on their own terms and stimulate virtual learning.

VR and AR technologies are less pervasive in archival instruction and outreach applications thus far. The US National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) launched a do-it-yourself augmented reality initiative in 2010 known as “History Happens Here”. The project is a low-tech contest where users snap a picture of an historic photo from the NARA holdings using its geotagged location to create a mash-up of past and present (NARA 2010). Remix techniques such as these are creative and provide a different type of access to archival records, but they do not meet the rigor of archival authenticity standards which can limit their usefulness in instructional settings. However, librarians and archivists guiding students through VR or AR interactions with archival materials may use this opportunity to discuss elements of information and archival literacy.

Major AR techniques detect target items based on location or trigger objects, such as images, artifacts or simple QR codes, and then project digital content on these items to improve user interaction and enhance their experience with the environments. The trigger object technique has been utilized with both real objects and in virtual reproductions, such as an image or drawing of an artifact. AR allows users to interact with an overlay of related digital content on top of physical objects. The Playing with the Artwork project applied such a design approach. Users first color digital representations of artwork without knowing anything about them. Then they go out on a scavenger hunt to find these pieces in the museum and compare their coloring with the actual artworks. When users point their app at a matching artwork, it triggers the app to display contextual information about that piece (Pucihars, Klijun, and Coulton 2016). The idea of learning while playing with technology is the highlight of this approach. The Playing with the Artwork project study proves effective among children.

In addition to the rich information AR adds for learners to understand the objects or environments, some designs break spatial boundaries by adding virtual avatars and thus bringing the interaction opportunities to users. Chen’s study designed a museum guidance system offering visitors the ability to interact with 3D scanned items at access points. Additionally, the access point provides contextual information about the artifact. If browsing triggers visitors’ interests, they will be guided to the location of the item within the museum (Chen, Chang, and Huang 2014). This helps visitors curate their own experience at the museum, leading them to the most relevant information for their interests before going to see the item in the exhibit. This prototype could be deployed in schools and other spaces to display educational content. Similar to museums, archives could benefit from such a mechanism for distilling information in a way that is relevant and approachable.

Another category of AR design integrates multimedia content with the actual artifact or environment and enables visitor-object interaction with AR control. One merit of this approach lies in exploring extra information about an object that is not visible to human eyes. The Revealing Flashlight project overlays 3D scanning and visualization of an object’s surface geometry. Users can use AR control to interact with the object and explore its properties by projecting the information of 3D layers instead of directly touching the objects (Ridel et al 2014). This design is of particular value for interacting with fragile materials with which the archives prohibit direct human contact for preservation purposes.

Different from AR, VR typically does not rely on actual objects or environments. Instead, it creates a virtual environment that replicates the reality and offers an immersive experience. The Virtual Experience on an Aircraft Carrier project in China creates a virtual flight experience where visitors interact with other players in the scene (Lu and Zhou 2016). Most VR initiatives to improve and enhance user experience with historical environments and artifacts are designed as games. In Spain, the PLAYHIST experiment used VR recreation of historical events with 3D artifact models to test users’ learning effectiveness through playing historical characters and reliving the historical moments (Aguirrezabal 2014).

In 1994, the National Science Foundation (NSF) implemented a grant program called the Digital Libraries Initiative. Through this program and cooperation with the National Initiative for Networked Cultural Heritage (NINCH), the NSF sought ways technology could address needs in the humanities fields. The Virtual Vaudeville Prototype received funding through the Phase II cycle of the Digital Libraries Initiative to explore ways “to use digital technology to address a problem fundamental to performance scholarship and pedagogy: how to represent and communicate the phenomenon of live performance (Sutherland 2016, 393). Project manager, David Saltz a performance scholar at the University of Georgia headed a national team of computer scientists, 3D modelers and animators, professional actors, and subject matter historians. The group set out to create “an archives of experience” that could recreate a dynamic sense of place with on-stage, backstage and audience activity presented in an interactive virtual environment (Saltz 2001). The prototype as written was not fully attained due to time and funding limitations and the work silos created by different institutional teams. The Virtual Vaudeville Prototype launched in 2004 and was last updated in 2005. It has since gone dormant, but the animations are available through YouTube.

VR, AR, and Archives: Techniques, Applications and Hurdles

VR creates a labyrinth of possible connections and deep explorations when incorporating archival materials in teaching and outreach settings. Total immersion allows for documents, photographs, drawings, and other artifacts to be understood in context (Craig and Georgieva 2017). The objects that tell the story of a person’s life or a business’ creative output are seen in a more organic than hierarchical order. For instance, the scrapbooks of H. Wayne Patterson, class of 1912, provide a snapshot of what student life on the Georgia Tech campus was like in the early 20th century. Combining historic documents, photographs, audio, and visual materials into a VR project would allow students to walk through a virtual timeline, learn about major changes in Georgia Tech policy, solve equations with a slide rule, and get a sports lesson from legendary Coach John Heisman. Through such an experience different audiences see the evolution of the school and community.

VR immersive qualities are ideal for instruction of technical and detailed lessons. When combined with archival records, solutions to current challenges could be tried without fear of failure. The Guggenheim Building at Georgia Tech houses a wind tunnel used to test numerous products including fighter planes, radar antennae, and the soil scoop arm for NASA’s Curiosity Mars Rover. Since the wind tunnel’s initial construction in 1929, the station has undergone several modifications and upgrades to keep up with the technology. Using blueprints, drawings, and photographs of the iterations of the wind tunnel system, aerospace engineers are able to see the building blocks of their current tool. Incorporating these records into a virtual reality environment would allow current aerospace engineers to peel back the layers of information. This illustration also has the effect of transforming archival materials into an interactive game allowing for meaningful connections with a non-traditional audience.

With its advantage of interacting with the physical environment, AR technologies could be applied to archival materials to facilitate instruction and student engagement in various projects. The virtual-real interactive capacity of AR enables loading multiple attributes including surface geometry, inside structure, and extra metadata. With AR, users can explore attributes that are not visible to them in traditional archival display and instruction. One possible application is to scan archival records documenting the 1996 Summer Olympic Games hosted in Atlanta with a number of events held on Georgia Tech’s campus. Currently, archives users cannot interact with some items for preservation purposes, like Olympic hats and shirts. This barrier prevents them from gaining an experience beyond just seeing these items. In an AR design, the hats and shirts could be reproduced with 3D scanning. Users would be able to pick them up and put them on virtually during archival instruction without damaging the originals. AR-facilitated interactions could change archival instruction from traditional lecture to more active learning.

In addition to enhancing user experience in an instruction setting, AR also brings archival experience out of a restricted space into a larger community. One possible application would be to scan historical images around campus. These images could be embedded at their original location based on the geo-information in metadata. Students and visitors could use an AR phone app to find these images around campus, read the history and compare the change of campus over time. This design not only breaks the physical boundary of archival materials, but more importantly, it also reaches out to a community that typically would not come into the archives to explore the collection. The enriched information and interactive experience of AR engages users and students in the classroom to learn about archival materials and inspires deeper and wider discussions.

AR and VR present a wide array of potential educational uses. However, compared to these hypothetical scenarios, there have been few applications of these technologies in archival settings or even in the college classroom environment (Johnson, Adams, and Cummins 2012). This disparity between the hypotheticals and the implementation is typical of early adoption with new technologies but also speaks to the steep learning curve and technological support necessary to develop these kinds of projects. Such hurdles include having access to necessary computing power such as gaming computers with high-end video cards and the high cost of 3D scanners. For effective implementation of educational methods utilizing technology, instructors need assurance it can enhance the learning experience. Without more practical examples in place, educators will be unable to develop a conceptual framework for how best to integrate AR or VR and archival resources.

Other hurdles librarians and archivists will need to address are long-term support, infrastructure, and preservation. This may be one of the more daunting aspects of working with AR and VR presently. However, archivists working with librarians are poised to address this issue as they regularly work to assist users with access to outdated media, digital repositories, and historical documents, while preserving access over time. As mentioned earlier, even with sizable funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF) and multiple institutions involved in development, Virtual Vaudeville went dormant and is no longer supported (Sutherland 2016). Long term preservation, access, and support need to be addressed early in the development process. This includes adequate publication platforms for these types of projects. Without a robust plan for sustainability and thorough documentation outlining how a project will be maintained moving forward, any changes in personnel or organizational adjustments could derail these technology-rich projects.

Unique to archival collections are issues related to donor privacy and the validity of historical records or artifacts. With AR and VR as a channel for user interaction in the archives, there is the potential to radically change the context in which an artifact or document is presented. This aspect opens discussion around authenticity in information sources and the role technology plays in disrupting. The importance of exact replication hinges on the design intention of the AR or VR project. If the end goal of the project is engagement and enticement of new users with the archival materials, then dependency on the virtual item as the absolute authority is unnecessary. However, in a VR or AR project that intends to contribute to scholarly research, the virtual representation of the archival object must capture all of the information content conveyed in the physical resource.

Even then, in the material transformation, digital surrogates cannot completely convey the aura of the physical resource or replace the original artifact. Walter Benjamin’s theory regarding mass reproductions of original art works in his 1935 essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction is relevant when grappling with the concept of authenticity in reproductions of original materials in VR/AR environments. Benjamin writes, “The presence of the original is the prerequisite to the concept of authenticity…The situations into which the product of mechanical reproduction can be brought may not touch the actual work of art, yet the quality of its presence is always depreciated” (1968, 3-4). A replica of an original object is at best a mirrored representation, but it lacks the presence of the original that extends from its creative context and subsequent journey. Therefore, the reproduction is of lesser value than the original item. Interacting with a reproduction of an original object is not the complete experience for researchers, but where it lacks aura, duplications provide increased access to the object.

This article does not judge the socio-economic ramifications of reproducing archival resources but suggests that the reproduction should be specifically presented as such to promote transparency of the information object. Librarians and archivists in instructor roles may use the topic of reproductions in the archives to discuss scholarly interpretation and analysis of original sources. The authenticity of the rendered copy in virtual or augmented reality supports the development of information and archival literacy. For example, the Association of College Research Libraries’ Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education instructs the information literate student to “use research tools and indicators of authority to determine the credibility of sources, understanding the elements that might temper this credibility” (American Library Association 2015). The additional VR or AR access point to the archival record encourages discoverability. The student may then do a comparison of the physical object to the digital surrogate if and when the project demands that verification.

Applications of VR and AR with archival materials come with need to evaluate donor consent to these types of uses, copyright restrictions, and other sensitivities before including the materials in outreach and instruction efforts. Duff and Haskel note how “Eliminating all control, or opening up the archives to all uses, may not be appropriate or acceptable when dealing with sensitive records that can distress, dismay or impinge on a person’s most private moments” (2015, 54). To this end the collective archival thought is barely brewing and there will be a need for revised policy or statement of principles to help guide archivists through the new realities of teaching, outreach, and instruction with VR and AR tools. Ultimately, using these types of technologies will “engage more participants and more collaborators, but archivists will need to consider how these changes will affect their archives” (Duff and Haskel 2015, 55).

Future State Applications

Archivists and Librarians at the Georgia Tech Library are sensitive to the known hurdles and challenges to instruction with AR and VR technologies. To achieve long-term success, our future implementation of AR and VR project design takes consideration of available resources and parses the process into manageable components. Campus partners fill gaps and create a wide base of support for and use of the instruction designs.

Digital preservation, rapidly changing media, and ongoing technological support is a universal problem in a number of industries and educational fields. This issue spills over into potential scenarios and uses for VR and AR with archival materials. Georgia Tech Library recognizes the need to address this overarching challenge by designing and prototyping smart solutions with multidisciplinary partners. Librarians with functional expertise provide specialized technical skills and instructional design. Tonia Sutherland proposes that virtual reality technologies play a role not only in capturing the essence of archival materials but also in redressing silences in the archival record. The promulgation of VR and AR arenas using primary source materials explores the past and itself becomes a record of enduring value. Archivists play a significant role in guiding sustainable design of such projects, not only from a short-term service perspective but also with an eye towards creating new archival collections. With the guidance of Library Next’s project goals, the stage is set for librarians and archivists to explore radical, cutting edge service changes for teaching and engaging users in innovative ways.

Bibliography

Aguirrezabal, Pablo, Rosa Peral, Ainhoa Pérez, and Sara Sillaurren. 2014. “Designing history learning games for museums: an alternative approach for visitors’ engagement.” In Proceedings of the 2014 Virtual Reality International Conference, 6. ACM.

American Library Association. 2015. “Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education.” February 9, 2015. http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

Azuma, Ronald T. 1997. “A survey of augmented reality.” Presence: Teleoperators & Virtual Environments 6, no. 4: 355-385.

Benjamin, Walter, and Hannah Arendt. 1968. Illuminations. New York: Schocken Books.

Chen, Chia-Yen, Bao Rong Chang, and Po-Sen Huang. 2014. “Multimedia augmented reality information system for museum guidance.” Personal and ubiquitous computing 18, no. 2: 315-322.

Čopič Pucihar, Klen, Matjaž Kljun, and Paul Coulton. 2016. “Playing with the artworks: engaging with art through an augmented reality game.” In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1842-1848. ACM.

Craig, Emory, and Maya Georgieva. 2017. “VR and AR: Transforming Learning and Scholarship in the Humanities and Social Sciences” Educause Review . Accessed June 1, 2018. https://er.educause.edu/blogs/2017/10/vr-and-ar-transforming-learning-and-scholarship-in-the-humanities-and-social-sciences.

Di Serio, Ángela, María Blanca Ibáñez, and Carlos Delgado Kloos. 2013. “Impact of an augmented reality system on students’ motivation for a visual art course.” Computers & Education 68: 586-596.

Duff, Wendy M., and Jessica Haskell. 2015. “New Uses for Old Records: A Rhizomatic Approach to Archival Access.” The American Archivist 78, no. 1: 38-58.

Johnson, Larry, Samantha Adams, and Malcolm Cummins. 2012. “NMC Horizon Report: 2012 K–12 Edition (Austin, TX: New Media Consortium).”

Lu, Li, and Ji Zhou. 2016. “Virtual Reality Technology Based Developmental Designs of Multiplayer-Interaction-Supporting Exhibits of Science Museums: Taking the Exhibit of “Virtual Experience on an Aircraft Carrier” in China Science and Technology Museum as an Example.” VRCAI ’16 Proceedings of the 15th ACM SIGGRAPH Conference on Virtual-Reality Continuum and Its Applications in Industry, no. 1: 409-412.

Moore, Michael T., Tania P. Bardyn, Adam Garrett, Deric Ruhl, and Gili Meerovitch. 2018. “Virtual Reality in Academic Health Sciences Libraries: A Primer.”

National Archives. 2010. “See History in Your Reality: A New Flickr Photo Project!,” NARAtions: The Blog of the United States National Archives. Entry posted October 7, 2010. https://narations.blogs.archives.gov/2010/10/07/see-history-in-your-reality-a-new-flickr-photo-project/.

National Science Foundation, UGA Research Foundation. 2018. “The Virtual Vaudeville Project.” About Virtual Vaudeville. Virtual Vaudeville. Last accessed June 5, 2018. http://www.virtualvaudeville.com/info.htm.

Oliveira, Silas M. 2017. “Trends in Academic Library Space: From book boxes to learning commons.” Open Information Science2, (1): 59-74.

Ridel, Brett, Patrick Reuter, Jeremy Laviole, Nicolas Mellado, Nadine Couture, and Xavier

Granier. 2014. “The revealing flashlight: Interactive spatial augmented reality for detail exploration of cultural heritage artifacts.” Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage (JOCCH) 7, no. 2: 6.

Rockenbach, Barbara. 2011. “Archives, undergraduates, and inquiry-based learning: Case studies from Yale University Library.” The American Archivist 74, no. 1: 297-311.

Rosenbaum, Eric, Eric Klopfer, and Judy Perry. 2007. “On location learning: Authentic applied science with networked augmented realities.” Journal of Science Education and Technology 16, no. 1: 31-45.

Saltz, David. 2001. “A live Performance Simulation System: Virtual Vaudeville: Project Summary.” National Science Foundation Grant Proposal.

Sharma, Sharad, Ruth Agada, and Jeff Ruffin. 2013. “Virtual reality classroom as a constructivist approach.” In Southeastcon, 2013 Proceedings of IEEE, pp. 1-5.

Sutherland, Tonia. 2016. “From (Archival) Page to (Virtual) Stage: The Virtual Vaudeville Prototype.” The American Archivist 79, no. 2: 392-416.

Vong, Silvia. 2017. “A Constructivist Approach for Introducing Undergraduate Students to Special Collections and Archival Research.” RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage 17, no. 2: 148-171.