Kate Singer, Mount Holyoke College

Abstract

This essay discusses digital encoding both as a method of teaching close reading to undergraduates and as a technology that might help to reassess the terminology used in literary reading. Such praxis structured a textual encoding project designed for upper-level undergraduates who constructed an edition of “Laura’s Dream; or, the Moonlanders” by nineteenth-century poet Melesina Trench. The painstaking process of selecting bits of text and wrapping them with tags reframed reading as slow, iterative, and filled with formal choices. By using the Text Encoding Initiative’s broad-based humanities tag set, students reflected upon classical literary terms as well as TEI’s extensible vocabulary, considering how best to formalize an interpretive reading. Since most women poets of the period taught themselves poetics, Trench’s poem became a test case for whether alternate terminology might best describe her experimentation. Important discoveries included differences between the term “stanza” and TEI’s “line group” tag (<lg>), and between labeling figurative language with classical terms such as “metaphor” or with the “segment” tag, marking self-identified tropes threaded throughout the poem (<seg ana=“visuality”>). As they tagged and then color-coded their readings, students gained the editorial prowess and creativity to develop interpretive language beyond rote or prescriptive terminology.

Introduction: Undergraduate Encoding for Close Reading

Perhaps no ability is as valued in undergraduate English classrooms as close reading. Students are taught to identify critical features of a short poem so that they can describe a work of literature and, hopefully, tangle with a myriad of cultural artifacts in sophisticated ways. For many scholars trained in more recent methodologies sensitive to history, context, and the market factors that shape textual transmission, close reading still retains a modicum of ideological baggage from New Criticism. Approaches that focus exclusively on the ambiguities of a poem’s form, syntax, and the minutiae of language and may end up treating works of literature as art objects hermetically sealed from social context. Nonetheless, students who are taught to identify tone, diction, genre, word order, meter, or metaphorical patterns can conceivably apply critical vocabulary to forge an argument about a work’s significance. They acquire a method of procuring a text’s worthwhile meanings even as they gain purchase on reflective reasoning, analysis, and argumentation—hopefully with clarity, precision, and sound evidence.

So the argument goes, and many of us are still attempting to tout the relevance of such critical thinking skills for the job market and the life of the mind beyond the classroom. The digital encoding of texts may be of help in such efforts, offering one means of bridging academic and public acts of interpretation, even as it helps us think through the ways in which digital media are steadily altering our ways and means of reading. The now-pervasive practice of marking up texts with code is widely understood to bring to light the historical and “textual situation” of a piece of writing by way of contrast with our own digital milieu. Even more acutely, however, digital encoding can become a method of close reading that reimagines literary analysis as a wide-reaching group of skills including searching, sorting, and identifying different sorts of elements—those information-management skills so necessary in light of the ubiquity of reading in the digital age.

As a result, one growing trend in teaching with technology entails student projects that execute digital editions of scholarly works. Students are asked to transpose, encode, and present literature to their peers and to the world at large, learning literary editing while producing scholarly work. The premier technology for many humanists has become the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI), a delimited set of XML tags aimed at describing literary, historical, and other humanities documents, markup which is then transformed by other stylesheets to present online. While HTML allows users to encode mainly presentation details (how a browser should display paragraphs, fonts, or images), TEI allows the editor to layer descriptive or analytical meaning into a text’s digital documentation—paragraph and stanza structure, meter, bibliographic details, people and place names, manuscript alterations, and so forth—while leaving web presentation for later. Figure 1 demonstrates a simple TEI encoding of the first stanza of John Donne’s “The Progress of the Soul.”

For additional examples of more complex poetry encoding, see TEI By Example’s use of rhyme tags in Charles Algernon Swinburne’s “Sestina” and that site’s example of manuscript encoding in Emily Dickinson’s “Faith is a Fine Invention.” This site also provides numerous other examples of TEI prose and drama markup in action. Romantic Circle’s recent scholarly editions provide their TEI XML files for viewing, such as this Robert Southey letter, which serves as an instance of encoding for people and places, with such references identified via <ref> tags that allow multiple documents in the large archive to cross-reference people and place names.

Because the encoding process is a painstaking one of selecting and marking discreet pieces of text, then wrapping them with tags in pointy brackets, it offers—especially for undergraduates—a dynamic, hands-on method for self-conscious, unhurried reading. While TEI was created for the purposes of digital encoding and, by and large, for storing, editing, and curating textual documents, the practice of encoding effectively engages the encoder in a determinative act of reading. Students accomplish a sort of digital highlighting as they label, categorize, and sort various areas of the text, using a set of tags or terms that are both familiar and unfamiliar. Their decisions about which structures and information to tag very much determine what they value in a document—or at least what should be preserved and codified for other readers. This highly structured and rigorous process encourages readers to slow down and engage in iterative, self-reflexive interpretation (Buzzetti 2002). For this reason, encoding—and teaching encoding—might be a valuable pedagogical tool, to enhance “close reading” and, additionally, to refocus reading as method of evaluative labeling, categorization, and selection of discrete bits of text.

Even more provocatively, encoding can help us rethink the very labels and terms we use to read. Digital markup languages for the humanities such as TEI build a comprehensive language for description and analysis, furnishing a revised, wide-reaching vocabulary for describing texts. In doing so, such a language can help us reflect—and facilitate reflection—on the literary vocabularies we have inherited from New Critics and Classical rhetoricians, including the types of assumptions and ideologies such terminology may carry with it. One prominent example comes from TEI’s struggle with finding tags to mark figurative language. While the Guidelines provide standard tags for stanza structures, people and places, and meter, there is a paucity in the TEI for literary forms and figures of speech and thought—a lack that presents an important and interesting problem through which to reconsider the project of close reading. The TEI P5 Guidelines for verse end with this well-known and important caveat:

Elements such as <metaphor tenor=“…” vehicle=“…”> … </metaphor> might well suggest themselves; but given the problems of definition involved, and the great richness of modern metaphor theory, it is clear that any such format, if predefined by these Guidelines, would have seemed objectionable to some and excessively restrictive to many. (6.6)

In shying away from such restriction, this aspect of TEI might seem to limit the descriptive or analytical possibilities of XML, particularly for those literary scholars schooled in poetic and rhetorical terminology. What should editors do who want a more extensive, analytical language to mark up verse? Could—and should—critics use TEI’s robust categorizing and descriptive capabilities to help catalogue a text’s literary features? Given the richness of classical terminology and poetic labeling, it would seem as though the paucity of tags for poetry might be limiting in the kinds of ways that other types of tag sets—such as those for historical places and names or for manuscript editing—are not. Of course TEI’s opportunity for customizing or creating one’s own tags could easily provide an individual solution, though one that would not be as readily available to other users. To take another view, however, the TEI’s intentional swerve from traditional, specialized, poetic vocabulary presents perhaps an extremely powerful and valiant challenge to received literary terminology. Since TEI is, at heart, an analytical and descriptive language for the humanities, it might encourage us to rethink which labels, categories, and values are essential in contemporary literary criticism and which terms may be unhelpfully ideological in our efforts to analyze literary texts.

Terms such as personification, synecdoche, or alliteration certainly can help readers to find observable, meaningful poetic patterns, but they do so by dictating specific figurative relations or sounds—designs often used by Roman rhetoricians as blueprints for invention and composition. Students who understand alliteration will look for repetitive consonant sounds at word beginnings and may even infer that such patterns occur elsewhere in the line. Alliteration and similar terms, however, do not necessarily encourage students to think more globally about all different sorts of sound patterns that may be more unique—and which may not have a term to identify their structure. Similarly, locating specific stanza forms, such as couplets, can blind the reader to more flexible or global formal experiments that combine couplets, quatrains, and other nebulous units into less recognizable structures. Finally, many figurative terms such as prosopopoeia (personification) presuppose a specific abstract relation, such as the representation of human characteristics in an animal or inanimate object. These connections likewise authorize very specific ways of reading the links between the literal and abstract (“being endowed with human characteristics”) rather than allowing the reader to identify the abstraction at hand (Shakespeare’s “teeming earth”), to understand the various concepts evoked (movement, excess, fecundity), and only then to build an understanding of how such a figuration might rethink ideas about what it means to be human. To put this another way, students looking for personification in a text may look for human characteristics narrowly defined—e.g., body parts or occasions when the inanimate becomes a person—rather than describing a figure’s human vitality on its own terms.

TEI’s broader language for poetic encoding, particularly when it comes to figurative language, may actually allow for greater creativity and ambiguity in marking poetic features, a tactic that can be quite liberating and helpful to students learning poetic vocabularies, concepts, and interpretive strategies. Students can learn to interrogate poetics terms and interpret texts in descriptive rather than prescriptive ways precisely because they do not automatically resort to classical literary terminology. In doing so, we can begin to see the potential for TEI to be used as an analytical tool in developing alternative poetic vocabularies and methodologies of reading.

What follows is a discussion of the experiments and debates about TEI as a descriptive, analytical language for poetic texts that occurred mainly during an undergraduate senior-level seminar on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century English women’s poetry. In order to plan the teaching of TEI to undergraduate literature students effectively, however, these queries also extended to discussions with colleagues in TEI seminars at Brown’s Women Writers Project as well as conversations with upper-level students, colleagues, librarians, and technologists at Mount Holyoke College and with humanists and digital humanists at other institutions. The basic digital venture was to have students build a TEI-encoded electronic edition of a poem by an obscure woman writer. I selected Melesina Trench’s “Laura’s Dream; or The Moonlanders” in part because, as a lunar voyage poem, its science fiction-like imagination of inhabitants on the moon prompted discussion about women and technology—helping the class to theorize both the imagination and language as early technologies. Moreover, the plot of the poem likewise allegorizes pertinent issues of pedagogy. Laura awakens from a fever-induced vision to tell her mother about her vision of the Moonlanders. While Laura’s mother dismisses these dreams as products of an over-heated brain, Laura’s allegories about the lunar beings reach toward truths culled by the young (who play with technology) and taught to an older generation. This view of technology and youthful experimentation was aimed at giving students a way to think about the process of using technology—both the ways they were being taught about it and the ways that they might instruct their teachers. Above all, students gained a new type of editorial agency that gave them permission to explore, alter, and retranslate the text for themselves and their peers.

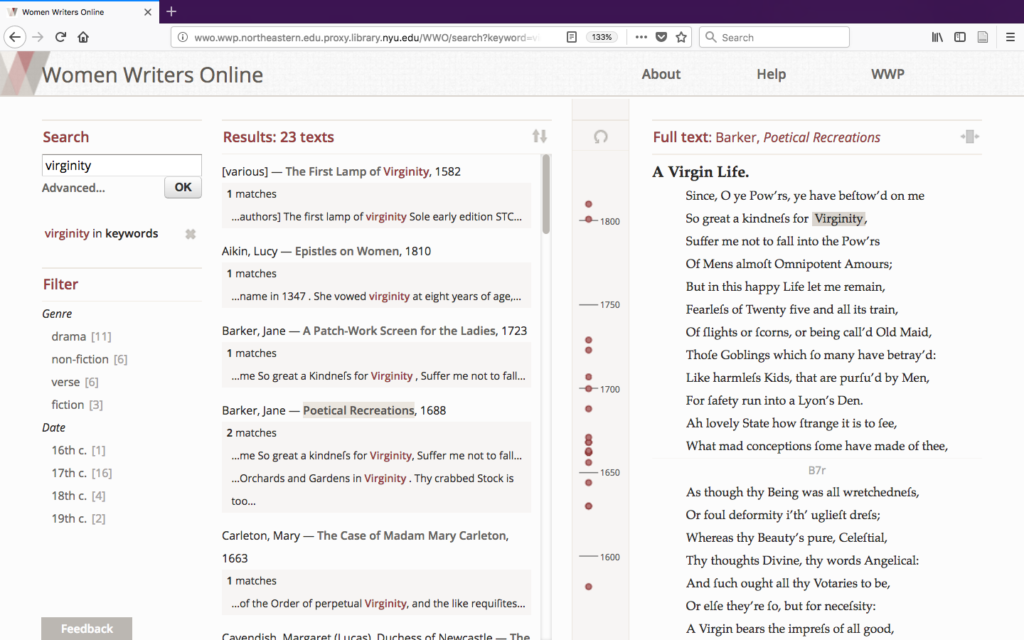

Additionally, the time period studied in the course—the Romantic century—specifically helped to promote questions about textuality and terminology. This period is now well known among scholars as one that included a print explosion, as the French Revolution and its aftermath spawned a prolific public debate in which women took a very vocal part. Women’s writing of this era, moreover, has had a intimate relationship with digital textuality in our own recent past. Over the past thirty years, new historicist scholars have boldly recovered much women’s writing from the archive, which has slowly, in bits and pieces, become part of syllabi, readers, and editions, if not the high Romantic canon of Wordsworth, Coleridge, Blake, Keats, Shelley, and Byron. Much of this large body of work was initially published electronically, and electronic texts often still supply important historical or standard editions of Romantic-era writing for scholars and students alike. To trace this institutional history, one need only mention a few well-known resources—Brown’s Women Writers Online, UC Davis’ British Women Romantic Poets or Romantic Circles’ editions of Anna Barbauld, Maria Jane Jewsbury, Felicia Hemans, and Mary Shelley. Much of this editorial work has aimed to reflect on both the historical contexts in which women were writing and the various print venues available to women—particularly those media and genres (such as gift books or weekly newspapers) that diverged from the standard, expensive volume published or printed by well-known establishments. The pervasive contextual approach is part and parcel of the new historical methodology that scholars used to rediscover women writers. The use of TEI with such scholarly editions, however, has the potential to help scholars of women’s writing intimately understand women writers’ styles, figurative propensities, and other technical aspects of their work that have been much less attended to—in part because of our dependence on classical rhetoric and literary terms. Many scholars have begun to look to “new formalism,” a methodology that melds New Critical concerns about form and style with New Historicism’s attention to history, politics, and market culture, in order to understand the historical and political implications inherent in forms and genres, especially the ideologies they carry with them. Scholarship on women’s poetry has just begun to pay attention to such concerns, and digital markup may be a tool to examine conscientiously both the structures and cultural contexts that make up women’s poetics.

For these reasons, scholarly questions about women’s poetics during this period seemed to intertwine intrinsically with questions about the encoding of poetry using TEI as an analytic language. When teaching canonical poets such as Shelley or Wordsworth, one would not think twice in using classical rhetoric or poetic terminology—such as personification, catachresis, or apostrophe—terminology that these authors were taught in English public schools through intimate knowledge of Greek and Latin. Certainly some women learned classical languages, yet many were autodidacts more versed in modern languages, and it stands to reason that they may have invented or played with poetic categories during such self-teaching. Thus when one begins to teach women’s poetry not merely as a piece of cultural history or cultural studies but as poetry in its own right, one wonders how such terminology intersected with women’s own understanding of their poetics. Much of our current thinking and use of poetic terminology developed through decades of reading that did not include much women’s writing, as Jerome McGann discusses in The Poetics of Sensibility. TEI’s own resistance to such vocabulary may, therefore, induce us to think about how we label different sorts of poetic moves or how we might redescribe women’s writing in ways more endemic to and descriptive of their actual practices.

In discussing the Women Writers Project’s editorial policies, Julia Flanders (2006) writes, “Given that our expectations about meaning and the conventions for [a text’s] expression are based overwhelmingly on the textual tradition with which we are familiar, it seems theoretically important not to allow these expectations to ‘correct’ a dissenting text into conformity” (142). Though Flanders discusses the Project’s tendency toward very diplomatic transcriptions, something similar might be said about the desire to exempt women’s texts from conforming to descriptive vocabularies that literary scholars developed by and large without reference to those texts. While some women’s writing is clearly written within or in resistance to canonical writing—for example eighteenth-century Bluestockings (Curran 2010, 172-173)—other verse may be much further outside our poetic and terminological toolbox. While our first impulse might be to add TEI tags culled from language already available and adjudicated in classical models, the vacancy in the guidelines opens up important questions about poetic terminology, allowing individual students encoders to make meaningful, independent editorial choices. Self-reflexive use of TEI might help open a space of new historical reflection on the ideological import of categorizing and descriptive practices then and now.

It might be important to remember that literary scholars have used TEI to mark up many important electronic literary editions, and the tags they employ certainly shape those versions of literary texts, whether or not we can see such markup by browsing through editions on the web. The World of Dante website has thoroughly encoded people, places, creatures, deities, and structures, and a clickable reading interface allows readers to select such features to highlight within the reading text. This kind of encoding (and its dynamic interface) visibly highlights important facets of the verse, and it arguably focuses readers’ attention on The Divine Comedy as a collection of locations that house people and supernatural beings. Editions of letters, like the The Collected Letters of Robert Southey mentioned above, may choose to focus descriptive tagging on people and consequently privilege, perhaps rightly, the letters as a source of social and literary networks. Even more subtly, editors may select a means to highlight the intricate structures of texts beyond the level of the paragraph or the stanza. The Whitman Archive’s Encoding Guidelines for marking structure includes a discussion of how editors designate poetry, prose, and “mixed genre” within the archive’s wide variety of manuscript materials—generic distinctions that may offer theoretical insight into the generic complexity and interpretive possibilities of Whitman’s work. It would behoove us, then, to wield what Perry Willett (2004) identifies as a productive skepticism toward markup in two ways: first toward our own literary taxonomic tendencies and second toward those ideologies hidden in TEI’s vocabulary.

Since many encoding decisions lead to some degree of interpretation (as does much editing), some sectors of the digital humanities and tech-savvy literary communities have been reticent in using TEI to mark up even more blatantly interpretive attributes of text such as figurative language. James Cummings (2007), in his introduction to TEI in A Companion to Digital Literary Studies, canvasses this under-explored topic:

It is more unusual for someone to encode the interpretive understandings of passages and use the electronic version to retrieve an aggregation of these (Hockey 2000: 66-84). It is unclear whether this is a problem with TEI’s methods for indicating such aspects, the utility of encoding such interpretations, or the acceptance of such methodology by those conducting research with literature in a digital form (Hayles 2005: 94-6). (455-56)

Undergraduates with less codified attitudes towards poetic structures and methods of interpretation may provide a wonderful test group to explore the utility of interpretive coding. At the same time, a digital experience early in students’ careers might lead the way to greater acceptance of such digital-analytical ventures. It may be very helpful to teach the next generation of digital humanists to think through the boons and banes of formalizing interpretation at the very moment they are learning to define notions of text, interpretation, or markup. As McGann and Dino Buzzetti have argued,

Markup should not be thought of as introducing—as being able to introduce—a fixed and stable layer to the text. To approach textuality in this way is to approach it in illusion. Markup should be conceived, instead, as the expression of a highly reflexive act, a mapping of text back onto itself; as soon as a (marked) text is (re)marked, the metamarkings open themselves to indeterminacy. (Buzzetti and McGann 2006, par. 49)

Both markup and interface are needed to create an iterative experience for a specific set of users—users who may have trouble viewing the text as volatile. Whether or not one agrees to the extent of textual volatility McGann and Buzzetti propose, students sometimes have trouble conceiving of textual indeterminacy that can still be effectively analyzed and interpreted. Not only do we need to upend notions of textual stability, but we also need to help students learn how to identify and understand productive ambiguity involved with such a textual condition.

Dreaming Up a Workable Project

Because such a view of markup was taught within an undergraduate literature seminar without other digital humanities components, this section describes how the project and such ideas about terminology were framed. Specific conversations early in the semester aimed to contextualize and anticipate encoding as a self-reflexive editing and interpretive practice connected to other “analog” reading practices. First, we repeatedly used literary terminology in our close readings of poems but did so as a matter of speculation or argument by definition rather than merely regurgitating terms with a priori strict rules. For example, when discussing late eighteenth-century poet Charlotte Smith’s address to abstractions like sleep and solitude or to locations such as the South Downs, we would examine several terms at once, such as address, apostrophe, and exclamatory speech. I would remind students that not only were some of these terms created and used first to describe much older texts but that each poem might be redefining its terms in ways that would not necessarily adhere to normative models—historical or contemporary.

Second, we examined each poem’s contemporaneous textual situation as well as its contemporary iterations through editorial or digital culture. Many of Mary Robinson’s poems first appeared in newspapers and only later in volume form, a textual situation only sometimes made clear in digital or print editions. Similarly, Charlotte Smith’s sonnets went through multiple editions in her lifetime as she added poems to each edition, and we discussed how reading those poems both with and without that context altered our understanding of her seminal work. Most online editions did not gesture towards such a complicated and shifting environment for those poems, and students wondered what a digital edition that housed and cross-referenced many of the important iterations might look like. When we began to discuss Trench, we studied two electronic representations—PDFs of an 1816 volume and a basic digital transcription of “Laura’s Dream” available at English Poetry 1579-1830: Spenser and The Tradition Archive. That transcription is framed by an editorial column to the left of the text with several paragraphs of synopsis and information about the poem’s two contemporaneous reviews. Before these comments, however, there is a long blurb placing the poem into a very particular Spenserian context: “In the two-canto allegory of Laura’s Dream Melesina Trench presents a feminine revision of Paradise Lost drawing upon the imagery of Spenser’s Garden of Adonis and Milton’s ‘Il Penseroso’.” This representation of the text gave students the impression—before reading—that Trench was a minor Spenserian acolyte, without a reputation in her own right as the aristocratic diarist and member of the bon ton that she was. This editorial paratext, moreover, seems to substitute for other types of annotations, hyperlinks, or search capabilities that might enable other types of linkages—or encourage students to discover information for themselves. This frame helped to provoke a discussion about what assumptions student readers might bring to such a work and how even seemingly slight contextual materials had quite a powerful sway over the reader.

About six weeks into the semester, we entered into the back-end of the digital edition. I introduced TEI in two installments: first with a half-hour presentation that discussed digital editions and archives more generally, followed by a two-hour hands-on training to teach the encoding basics of TEI with the help of a student Tech Mentor and two tech-savvy librarians. Set up in a computer classroom, we walked each student through launching oXygen—an open-source XML editor—opening a pre-formatted XML document replete with an already populated header and two untagged stanzas of the poem. With the document open, students were guided through the document declarations and the header but not asked to replicate them. (These portions of the document contain instructions for browsers on the document’s status as an XML file and processing instructions as well as bibliographic information about the file and the literary text itself.) This method of introducing but then bracketing off such information for students resembles what Alex Gil and Chris Foster in their experimentation with teaching TEI at University of Virginia have called the “bottom-up model,” and it contrasts with many “top-down” TEI pedagogies that begin with encoding a document’s header and its larger structures before focusing on the text itself (Project Tango). It seemed important in this case to get students interacting with discrete pieces of the text as soon as possible, replicating the literature pedagogy of the seminar where students worked from the minutiae of the text outward. When they finally reckoned their markup with the larger structures of the entire text, they realized just how encoding—and the interpretive problems that arise—require an iterative process (McGann and Buzzetti 2006; Piez 2010).

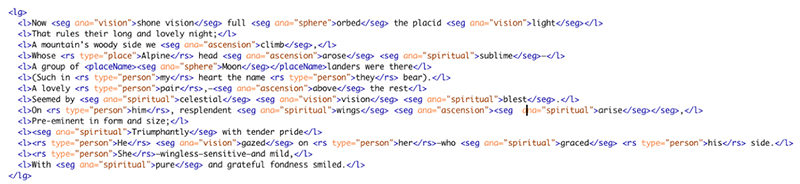

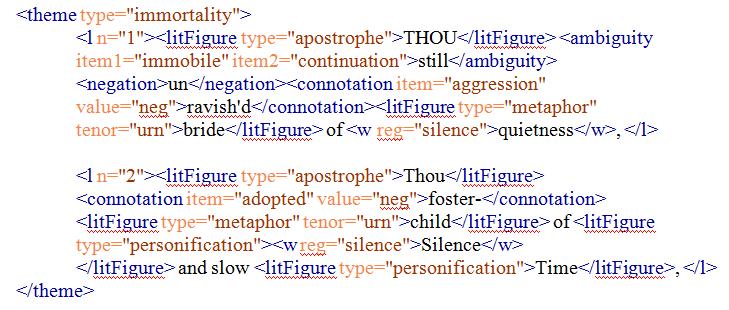

To tackle the intricacies of tagging, I mirrored on a large screen what students had on their own computers. We moved through the following elements, each of which they would use in their group projects: <lg> (“line group”, the TEI term for stanza), <l> (“line”), <placeName> (places with proper names), <rs type=“place”> (places without proper names), <persName> (people with proper names), <rs type=“person”> (people without proper names), ending with <seg ana=“…”> (the segment tag <seg> selects a specific piece of text, here associated with an editor’s choice of analysis, specified by the attribute, ana=“…”). We used this last tag for tropes, or figurative language that threaded or repeated throughout the poem, for example <seg ana=“vision”> or <seg ana=“affect”>. This tag became the most important of the project, since it allowed students the most freedom to select words or phrases and then label tropological categories without resorting to classical terms such as metaphor.

Figure 2. Sample encoding by group 3, using <lg>, <l>, <placeName, <rs type=”place”>, <rs type=”person”>, and <seg> tags.

Following this session, students were given the assignment sheet for their digital project along with directions to the necessary documents, which had been uploaded to folders for each group on our class website. The assignment largely replicated the in-class TEI tutorial but with a new and longer passage of about sixty lines. Students were placed in groups of three and asked to encode the following: 1) lines and line groups; 2) people and places (real, fictional, and mythological) both with and without proper names; and 3) between one to three analytical strings (<seg@ana>) that seemed especially significant to their group of lines. At the suggestion of members of Brown’s seminar on contextual encoding, I assigned the same set of lines to two groups each, so that we could compare and contrast how these line groups were encoded. Students were also given a CSS stylesheet that would allow them to color-code their tags, particularly the figurative tropes, so that we could visualize their encoding at the project’s end. Finally, they were to write up a short project report, analyzing what they had learned about the poem from encoding that they did not know before from simply reading it. The grading of the project would be three-fold, based on accuracy of the encoding, creativity, and their written reflections about TEI and poetics.

In hindsight, there were several adjustments that would have helped to teach TEI more efficaciously. Students often began coding with errors, forgetting, for example, the difference between <persName>, used for proper names, and <rs type=“person”> for other references to people, despite the cheat sheets given for reference. I was able to catch some of these coding errors because two groups voluntarily came to my office hours to ask other questions about their tagging. In response, I segmented about twenty minutes of class time the week before the projects were due to review some of these errors, but I was not able to catch everything. The next time I teach this project, I will make sure to have a more hefty review session, perhaps where groups workshop their coding during the seminar, allowing students to teach each other valid coding and to raise questions about particular, tricky examples that would benefit the entire class. Alternately, I might have a review lesson or two where we code another piece of a different poem, to give them another application for the coding concepts. For example, students might complete a short encoding exercise on one day focusing on tagging people, personifications, apostrophes, and so forth and spend another day marking up metaphors, similes, and related figures.

Part of the trouble, I realized, was that most of the groups did not often meet with our Tech Mentor, a senior English major who was not part of the class but who was helping with the TEI portion of the project. Students either felt they already understood the material or felt their expertise was equal to the mentor’s. If I used a Tech Mentor again, she would need to be a more visible and integral part of the class project. Ideally, I would have her help to introduce the TEI materials and perhaps serve as a project manager, not simply as a student with office hours in the computer lab.

Finally some students, at the end of the project, wanted more power to manipulate and change their own CSS documents. Originally, I had scheduled for us to do this together in class, once students had finished their encoding, but many students asked that they be able to change color coding as they developed and experimented with different markup schemes—requesting a truly iterative process. As a consequence, I made time before the project was due to show them how to change various aspects of their CSS and how to upload their documents into the proper directory structure so they could view changes to the text’s color and layout as they made them.

Formalizing Figurative Ambiguity & Conceptual Mapping

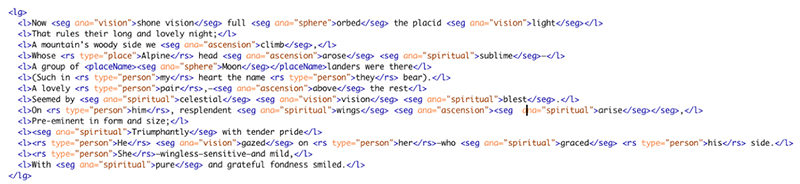

Figure 3. Sample stanzas of encoding by groups 1 and 2, using tags. The website flashes small, mouse-over labels for the first instance of the descriptive tag.

Above are two short samples of a stanza encoded by two different groups. Encoding done by all four groups is available on The Melesina Trench Student Edition site; visualizations discussed later in the paper can be viewed separately: stanzas by group 1, group 2, group 3 and group 4.

The project results spawned two interlocking questions for student encoders. How much literary data should editors formalize by tagging it for a readership of their (student) peers, and what is the best vocabulary to do so? Rather than move toward a more taxonomic approach to interpretive tagging than currently exits in the TEI Guidelines, the expansiveness of tags such as <seg@ana> and <lg> fueled student creativity and introspection about poetic categories and vocabularies. As Cummings (2007) writes, “What might jar slightly is the notion of a text’s ambiguity that informs most of New Critical thought; it is inconceivable from such a theoretical position that a text might have a single incontrovertible meaning or indeed structure” (458). If TEI users have been less interested in interpretive than editorial markup, perhaps it is because TEI appears to read both structure and meaning too definitively into a text that should be a resource or open set of data for any scholar to interpret at will. Yet, this may be more the fault of our blindness to the ways in which markup may act not as formalizing structures but can mark, instead, moments of textual instability, suggestiveness, or ambiguity. This method would pinpoint moments of figuration that educe both semantic or non-semantic abstraction. Certain TEI tags, precisely because of their ambiguity, became generative in such a way.

While contemplating the poem’s form, for example, we examined the difference between labeling pieces of poems as “line groups” rather than more specifically as stanzas, couplets, quatrains, or tercets. Noting that we could, if we wanted, designate an <lg type=“stanza”> or even use the “type” attribute to specifically describe the stanza such as <lg type=“couplet”>, we discussed what benefits were allotted to us if we thought of stanzas as line groups. “Laura’s Dream” uses stanzas of varied lengths, as does much other women’s poetry of the period. While Trench seems to be working from an eighteenth-century model of heroic couplets, she nonetheless groups stanzas of irregular lengths into chunks that seem amorphous, as they are built from couplets, quatrains, and other clusters of lines with alternating rhyme. The more general TEI term “line group” supplied us with a better or more flexibly descriptive language for these chunks of verse, as an interstitial form that Trench uses. In this way, the TEI vocabulary might enable a helpful reconsideration of codified stanzaic units in other, similar poems, enabling students to find moments of experimentation as well as codification. This kind of encoding may open the way toward discovering in women’s writing other types of micro-forms or more nebulous poetic structures previously invisible to eyes looking for quatrains, sonnets, or Spenserian stanzas.

Similarly, rather than gravitating to figures of personification and debating how and why something like “Genius” was personified in “Laura’s Dream,” students became more interested in discussing the difference between proper names (and places) such as “Arno,” “Greece,” “Laura,” or “Apollo,” and those more general entities without specific names, such as “valley” or “Lady Fame.” In the project reflection one group commented, “We especially noticed that there was only one ‘proper’ name and one ‘proper’ place throughout our entire fifty lines. This was surprising in light of the fact Aurelio and Laura’s adventure introduced them to many new creatures and locations. ‘Improper’ people and places were also sparsely dispersed throughout the poem.” This distinction helped students navigate the dreamscape of the poem in ways that emphasized its figural dimension. Rather than viewing the poem as an allegory that simultaneously and consistently operated in two places—Laura’s home, where she kept ill, and the moon, where she dreamed, the varying levels of referentiality mapped by the TEI elements across the poem revealed the “valleys” and “peaks” of the text where figural qualities of space and place, vision and imagination were heightened or intermixed. In a sense, the use of <rs> (used for people and places that did not have proper names) began to infect the more literal tags with hints of figuration. At the very least, these tags suggested how previously ignored phrases or words, such as “hidden recesses” or “flowing rivers,” might be potent with abstract meaning. While students considered the idea of the poem as a database of names and identifiers or women’s roles (what some text encoders have called an “ography”), the less visible people and places within the poem heightened their awareness of what sorts of literal (biographical, topical) information often gets attention in women’s writing (and perhaps encoding) as opposed to the more “improper,” abstract, and visionary people, places, and objects.

We held a comparable discussion regarding TEI’s more ambiguously descriptive language for figures of speech and thought. The <seg> tag, i.e., “segment,” can tag any length of text and, in doing so, resists the privileging of word, line, or lemma. As Susan Hockey once wrote, “There is no obvious unit of language” (Hockey 2000; McGann 2004). Rather than focusing on individual words or syntactical units, students instead roved the text for moments or nodes of figurative thickness where the poem seemed to move beyond the literal, without having to worry about how to match such moments to prescriptive classical structures.

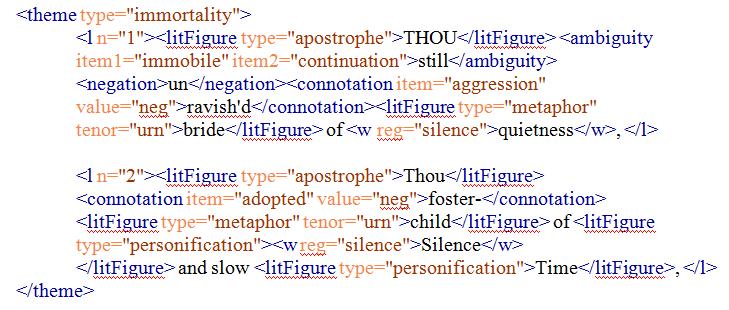

By way of a counter-example, we looked at the extended tag sets for sound, meter, tropology, and syntax that were at the time attached to the Poetry Visualization Tool and are now associated with Manish Chaturvedi, Gerald Gannod, Laura Mandell, Helen Armstrong, and Eric Hodgson’s tool called Myopia: A Visualization Tool in Support of Close Reading. This interface brilliantly employs four different customized tag sets that then enable users to visualize patterns in the poems, cross-referencing these different dimensions of reading. What follows are the first two lines of the tropological encoding of John Keats’ “Ode on a Grecian Urn”:

Fig. 4 TEI of “Ode to a Grecian Urn.”

There is much to say about this customized encoding, most obvious being the creation of <litFigure> tags with associated types. One might notice that the <litFigure> of metaphor takes a tenor attribute yet leaves the vehicle a bit less formalized, opening up the metaphorical transport for interpretation or readerly description. Even more alluring are the <ambiguity> and <connotation> tags with associated attributes. While <ambiguity> signals a word that might have several meanings or ideas in terms suggested by William Empson’s seminal New Critical work, Seven Types of Ambiguity, <connotation> encourages readers to label figurative or tonal meaning beyond a word’s literal denotation. Both tags allow the editor to formalize interpretations of nebulous and often subjective meanings.

In some ways, as suggested earlier, replicating standard terminology seems a missed opportunity to reconceptualize our approaches to poetic structures—particularly in an age when representations of structures may shift as they become computerized data. Rather than coding for specific literary figures, <seg@ana> encouraged students to find concepts and abstractions that circulate throughout a given text. While student groups did label each trope once they had identified it (e.g., <seg ana=“ascension”>), this labeling offered them the creativity to describe and define the type of abstraction—and how it operated in the text—on their own terms. Here was one group’s response to the procedure of figurative tagging, as they narrated it in their project reflection:

Our initial debate came when deciding how to word our tags. The first theme we chose was “decay,” but we had difficulty deciding if that also meant “dirt-related” imagery. We were unable to include as many words as we had initially wanted, so we revised our choices for tags. “Decay” became “morbidity” in order to more accurately describe the themes observed. “Dirty” became its own tag, and evolved first to “earthy” and then to “earth” so we could include all organic imagery. “Dirty” fit under “earth,” so we felt as if we were not losing anything in altering the tag. Rather, we were able to extend the theme. “Movement” as a tag did not ever change in wording, but we did debate over specific cases in which we wanted to use the tag. We had trouble deciding whether “movement” meant only physical motion, or if it included past actions or descriptive terms that implied motion.

The <seg> element often entailed ambiguating—rather than disambiguating—pieces of text, and it frequently provoked debate about how to do both at the same time. More acutely, coding in this manner helped students to work more readily on the abstract plane of analysis, moving beyond “theme” to discover language’s play with various levels of abstraction. Encoding enabled them to grapple with larger semantic issues without leaving the text proper and falling into universal generalizations. Most importantly, it did not freeze meaning so much as encouraged students to toy with tying the literal to the abstract in exploratory ways. The more generalized segment analysis challenged students to pinpoint where abstraction happens in a poem’s figurative terrain and then to map how attendant concepts mutate through a given passage.

There was something to segment tagging that was pleasurable and generative, even more than “analog” close reading. Students very much understood that they were reproducing their version of the text, and their readings took on an independence and intellectual verve due to such a sense of editorial responsibility. As one student commented, “It is really thought-provoking to contemplate how an encoding exercise such as this one is an act of appropriation, on the part of the encoder, in attempting to determine both what the poet wanted to emphasize and what the reader will, ultimately, extract from the encoded rendition of the poem; we are reshaping the reading experience in the author’s absence.”

Students took this self-reflexive method of iterative, renditional reading and mapped it onto to their “analog” reading of texts during the remainder of the course. While several students in their course evaluations mentioned their heightened comfort and skill with reading poetry, it was students’ final papers that revealed how the analytical habits learned in TEI encoding transferred to their reading practices with print texts. These final papers were written only a few weeks after students finished the TEI assignment, and we spent half of the final seminar discussing the results of these projects, while the other half was devoted to students presenting the initial findings of their final papers. Students were given free rein to write any sort of fifteen-page paper they liked that would build a substantial argument about one of the poets or a group of poems studied during the semester. The most palpable internal evidence that students were engaged in digital-style close reading was the complete lack of block quotes in all except one of the papers. Students were truly selecting bits of the text, then proceeding to define their poetic value in distinctive ways, even when making global claims. For example, one paper discussing Madame de Staël’s representations of various nationalities in her novel Corinne, focused exclusively on descriptions of the character’s physical and emotional characteristics. This reader, however, did not dwell on more obvious features but spent time with illustrations of characters’ hair, particularly the difference between Italian Corinne’s “beautiful black hair” and her half-sister’s English blond locks, “light as air.” The reader went on to make a particularly astute analysis of the simile—as well as the reason for the English hair being tagged with a simile while the Italian hair garnered only straight description. Perhaps many good English students might perform an interpretation responsive to the figuration of physical features, especially in a course on gender and poetics. At the same time, the student was especially attentive to the comparative instances of figuration and its lack—the different levels of figurative play within a single passage.

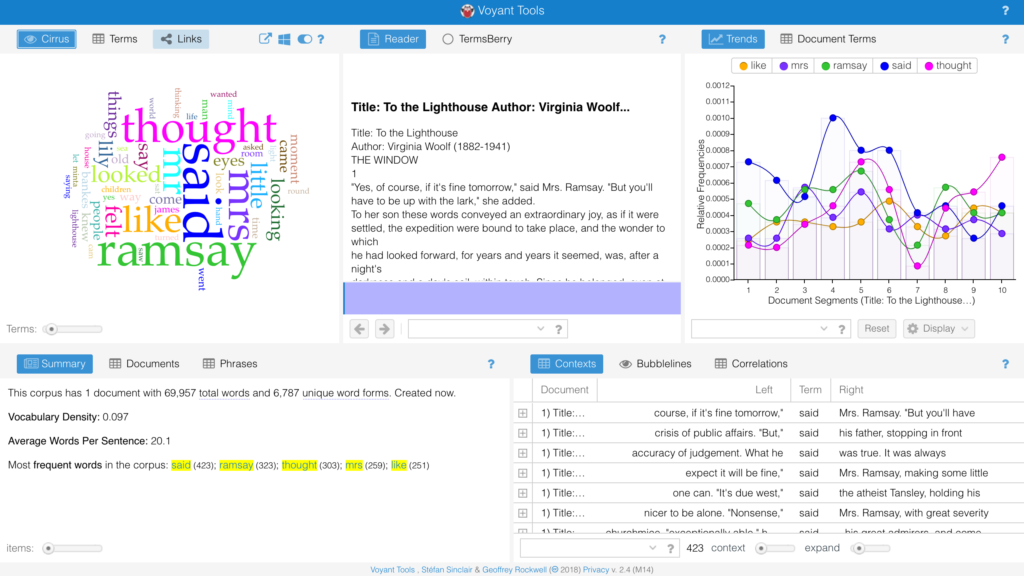

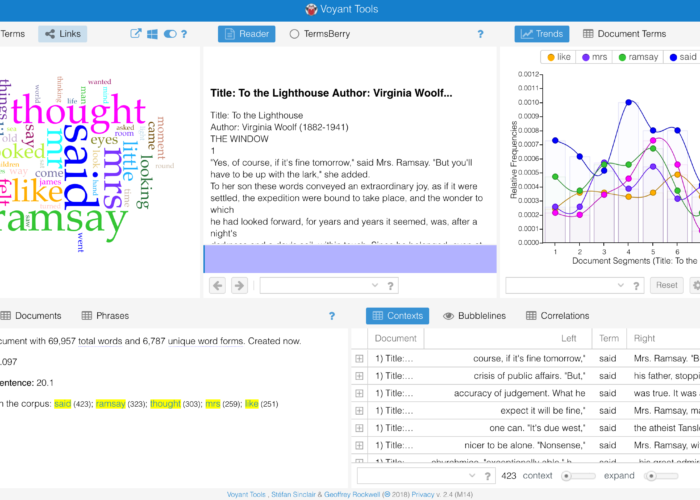

This particular consideration for figurative language and its trends throughout a poem presented itself even more strikingly in the scope and tendency of the students’ main arguments and interpretive techniques. Almost all of them chose make an assertion about the prevalence of one or more tropes in a particular author’s body of work. Some students used the word “trope” specifically in their thesis statements, while others employed such figurative concepts to sculpt and organize their analyses. (A Voyant word frequency analysis of the student papers as a corpus revealed that “trope” was the top technical term throughout the papers, used nearly as frequently as the word “poem.”) For example, one student working on the myth of the desperate poet in Mary Robinson and Letitia Landon’s poems argued, “Robinson and Landon create women of modern myth in sentimental poetry through tropes of voice, beauty and the performative.” Two students wrote about Elizabeth Barrett Browning with varying approaches to the language of maternity. One constructed the following thesis: “By using the trope of maternity, Barrett Browning gives audiences something perhaps more accessible with which to identify than slavery in order to nail home her belief that slavery is a crime.” The second came to an alternate interpretive conclusion because she identified the trope in a different way—as “motherhood”—emphasizing the figurative crux to be about feminine subjectivity rather than an existential or moral issue: “By exploring the trope of motherhood through varying lenses of naturalness, Browning rejects the uniformity of maternal conduct and allows for the construction of a feminine self outside the scope of a traditional, patriarchal role.” A student who wrote on Melesina Trench considered a shift in tropes throughout “The Moonlanders,” though quite separate from those discussed in class or through the TEI projects: “By replacing the traditional Romantic trope of the woman’s song with the woman’s dream vision, Trench offers a speculative fiction of a society void of institutionalized patriarchies in which nature can sing for itself and woman, though she lacks wings.” In one final example, another student used her paper to take on the Herculean task of questioning how we might define masculine versus feminine tropes during the Romantic period, cycling through multiple examples from multiple authors.

These papers employed the looser term “trope” learned during the TEI project without any prompting by me. They did so to cull figurative patterns for interpretation, often cross-referencing one trope with another to find correlations, associations, differences, and ambiguities between and among them. For example, the first paper on Barrett Browning sought to reveal how slavery and maternity worked together to create a certain moral affect, while the second looked at the multiple iterations of motherhood in differing amounts of tension with patriarchal roles for women. The paper on “The Moonlanders” similarly claimed that Trench rejected a traditional trope of song—which we had discussed in other women writers during the semester—and substituted the trope of dream vision to distance the poem from notions of institutional and patriarchal dominance. These students were invested in identifying figurative trends, their relations to each other, and the interpretive reasons why they trended together. Dueling notions of a single trope or the changing emphasis among multiple tropes helped students to articulate fluidity and ambiguity toward a particular concept within the span of a poem or an author’s body of work.

To be sure, some of these tropes might appear to be standard topics or representations often found in women’s writing, e.g., maternity, childhood, notions of femininity and masculinity, nature, death, and affect. The resort to classical or standard tropes in these papers might be read as student resistance to the more ambiguous or fluid tagging. The use of terms like “apostrophe” or even concepts such as “the gaze” reveals that some students certainly need or prefer more rigid, defined terminology. Moreover, not every poem may call for the qualities that “The Moonlanders” evoked, and students may have been sensitive to the need for more formalized structures or vocabulary in some poems while others required more ambiguous, fluid vocabularies.

Even these supposedly standard tropes, nonetheless, were atomized throughout the span of the papers into more complex or original designations. In this way, many papers exhibited the sort of iterative thinking that TEI encoding encouraged when students were asked to both identify tropes and then name (and rename) them in individual, unique ways. This sort of reading became apparent during moments in the papers where students would scrutinize, reassess, and redefine a term in multiple and unconventional ways. One student who used classical terminology, for instance, began with several claims about the relationship between affect and apostrophes to nature, using apostrophe as her major culling point. The argument developed, however, in increasingly interesting and individual ways such that, by the paper’s end, the reader had established for herself distinct terms of analysis including physical and emotional distance, emotional chaos, and emotional void. These last two terms organized the major part of the paper in a language that was the reader’s own and that allowed her to draw her own conclusions about the nature of address and how it worked to shape affect in the poem.

Another such case was a paper on Charlotte Smith’s “Beachy Head” that chose to take Lyn Hejinian’s term “open text” and modify it to “open voice” to document the specific figurative relationship between the eponymous coastal cliff’s open landscape and its ability to produce androgynous language with multiple meanings. Here gendered tonality was cross-referenced with the tropic tendencies of language describing both nature and history. Again, what was unique about the paper was that it not only fashioned a new term from an older one, but that it did so to elucidate comparative figurative trends and flexible concepts running through a poem.

The result of such tendencies in analysis was a particular attention to language, figuration, and especially the iterative creation of self-defined vocabularies to describe tropic trends. These papers were exceedingly strong on the analysis of significant linguistic tendencies. The emphasis on particularities and correlations that TEI emphasizes—correlative reading—did not, however, necessarily provide a ready mechanism for synthesis or cumulative interpretation. While final papers tended to dwell on the particulars of poems, some tended to be less strong on overall, synthetic arguments, and they struggled to link multiple tropes or trends into a singular argument about the work. For my purposes, I was comfortable with this unevenness because the observations themselves were fiercely interpretive, if not always global. Even though we did discuss the organization of longer papers in class, for the most part, these papers reflected the course’s distinct focus on generative analysis and strategies of reading that encouraged the creative selection and identification of dense poetic moments.

The Final Read: Generative Visualizations of Interpretive Coding

Figure 5. Sample visualizations of encoding by groups 1 and 2. For encoding & trope tags, see Figures 2 and 3.

The final piece of our attention focused on an undergraduate user-friendly visualization to help reproduce and interpret students’ analytical markup for both this seminar and others in the future. During the TEI hands-on demonstration in class, we used a CSS stylesheet along with oXygen’s “Open in browser” button to demonstrate how the CSS would transform the tagged XML document. Since cascading stylesheets assign fonts, colors, and spacing to individual tags, we chose it as a method of display that students would be able to learn and manipulate without too much difficulty. As mentioned above, students were especially gunning for the point at which they could transform their underlying encoding to “the real edition.” The disjunction between the encoding “signified” or genotype and the transformed document “signifier” or phenotype presented some important practical and theoretical issues (Buzzetti 2002). Students began to ask why TEI-encoded websites didn’t always have a button or function to display encoding to savvy readers, as another type of annotation or editorial self-awareness.

Our stylesheet had been written not only to display the verse in a clean format, but to highlight with distinct colors the contextual place and name tags as well as each of the <seg@ana> strings, enabling students to visualize figurative patterns across lines or verses and to augment the analysis of structures across traditional formal structures (McGann 2004). After doing so, they most frequently noticed the conjunction of certain tropes. For example, one group argued that the trope “religion is always within a line that is also tagged for emotion or male dominance.” A second group encoding the same passage, however, tagged similar phrases and lines with the tropes “spirituality,” “spheres,” and “ascension.” This comparative approach suggested a diametrically opposite reading based on their triangulation of three different tropes—a type of spirituality that enabled female transcendence rather than an institutional religion that codified masculine dominance and feminine affect. If nothing else, the clear encoding and representation of such markup revealed to students how two different readings could obtain equal validity.

At this point we compared our visualizations to other attempts to highlight themes and contextual encoding done by the Virtual Humanities Lab and Vika Zafrin’s Roland hypertext. These sites employ either colored sticky notes appearing on the margins with thematic and encoding information or, in the case of Roland, a clickable list of themes that highlights encoded lines in the poem. Unlike these verbal references, the purely sensory color-coding of the “Laura’s Dream” CSS (without overt reference to the trope name) established a non-verbal interpretive layer rather than another linguistic boundary. Even though students knew the colors were keyed to semantic categories, the visual rendering often momentarily lost its verbal reference and, in doing so, encouraged redefinitions and reinterpretations of a given trope. When we looked at visualizations projected on the classroom screen, we began to question how to encode something as slippery as affect—whether affect was, after all, a stable category or whether it was better to isolate various types of feelings, sensations, and desires into various categories. Different groups had keyed different shades of purple to melancholy and morbidity, and visualizing their similarity raised important questions about how to categorize, differentiate, and interrelate such close nineteenth-century tropes. This procedure seemed especially important for literature students who can be quick to assume they understand the definitions of historical trends such as sentiment, sensibility, or the Victorian cult of death.

In our discussions of visualizations, my students began to dream of an interface that allowed them to bring our class’s particular collections of text and commentary to bear on a primary text, one with the ability to then permit future classes to render their own versions in the space of the same edition. While tools like NINES offer the functionality of a digital collection, students envisioned a tool that could digitally “highlight” pieces of text, save these alterations, yet still leave the original open and blank for others’ readings. Because XML encoding often hides itself from view, TEI editions can give students a type of double-blind reading, where they can see a supposedly transparent document and then examine the editing and marking underneath. Moreover, since collections of texts and especially important passages change from class to class even with the same course, teaching editions might be built over and over again, by each class, compiling a reading database. This type of textual situation, using a relatively small text in a specific setting, might create one instance of a text with a computable repository of multiple, successive, yet interrelated student readings of a poem.

The students’ interest in interface and design, by the end of the project, revealed that they were thinking carefully about both authorial and editorial choices, including the coding decisions that compose the production of digital editions and other texts for the web. Their imaginary wish list of possibilities largely revolved around what kinds of functionality they might dream up for the next iteration of the digital edition. At the same time, students appeared to have a greater appreciation for the complexities of even the most simple looking web page. Rather than scoffing at the static nature of some web pages, as they did when we first began to look at various digital editions of Romantic period women writers, they were both more judicious and discerning as to the various intents and audiences of specific sites. Moreover, where many of them initially voiced a strong dislike of editions with too much editorial information, in particular revolting against texts with hyperlinks that were too directive in providing them with a particular interpretation, they came to see such sites as one type of edition among many. While at the end of the course we did not have time to discuss the editorial prerogatives of particular sites or digital editions, students did come away with the notion that the web and its texts can be added to and altered by its users—given the right skills. Thus, their most powerful response was to feel as though they now could help to create their own reading experiences—based on their own contrasting needs and choices. Several students went on to learn other digital tools (such as Dreamweaver, Photoshop, and additional XML), and others mentioned feeling more prepared to engage with the internet on their own terms and with an understanding of how sites might be constructed under the hood.

It might be easy to ask whether using highlighters and a hard copy of a poem would give the same results as digital close reading—and without the energy expenditure of setting up a TEI project. There are, however, a number of arguments in favor of such entry-level digitization. The Trench project taught students a very basic sort of encoding, introducing them to the idea of texts (or poems) as data but with familiar coordinates, based as it was upon close reading. It empowered upper-level students working in groups on questions of interpretation and meaning (Blackwell and Martin 2009), rescripting the scene of reading as a collaborative, social, and descriptive one rather than something more hermetic, fixed, and prescriptive. The physical, hands-on nature of a project where students literally rebuilt pieces of a poem and painstakingly marked it by hand resonated with them in ways that “analogue” reading did not. More dramatically, the broad-based “humanities language” of TEI enabled students to question, historicize, and reconsider the poetic terminology we use to describe poems. The expansive nature of its very language—in terms like “line group” or “segment analysis”—may pave the way for students and scholars to locate within women’s writing less formalized structures and figurative pathways previously unnoticed. What these forms and figures amount to, I would argue, are pieces of women’s conceptual thinking, which TEI can now equip us to trace and map. This kind of interpretive markup may, finally, give us some inkling of how TEI might be used as an analytical tool for smaller-scale, case-based projects perfect for undergraduates as they learn to parse and categorize their own textual situations.

Bibliography

Blackwell, Christopher and Martin, Thomas R. 2009. “Technology, Collaboration, and Undergraduate Research.” Digital Humanities Quarterly 3.1. Accessed February 27, 2011, http://digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/3/1/000024/000024.html.

Burnard, Lou and C. M. Sperberg-McQueen. “TEI Lite: Encoding for Interchange: An Introduction to the TEI.” Final Revised Edition for TEI P5. Text Encoding Intiative. Accessed March 24, 2013. http://www.tei-c.org/release/doc/tei-p5-exemplars/html/tei_lite.doc.html.

Buzzetti, Dino and Jerome McGann. 2006. “Critical Editing in a Digital Horizon.” In Electronic Textual Editing, edited by Lou Burnard, Katherine O’Brien O’Keeffe, and John Unsworth, 53-73. New York: The Modern Language Association of America. Accessed April 24, 2013, http://www.tei-c.org/About/Archive_new/ETE/Preview/mcgann.xml. OCLC 62134738.

Buzzetti, Dino. 2002. “Digital Representation and the Text Model.” New Literary History 33.1: 61-88. OCLC 4637615635.

Cummings, James. 2007. “The Text Encoding Initiative and the Study of Literature.” In A Companion to Digital Literary Studies, edited by Ray Siemens and Susan Schreibman, 451-476. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. OCLC 81150483.

Curran, Stuart. 2010. “Women Readers, Women Writers.” In The Cambridge Companion to British Romanticism, edited by Stuart Curran. 2nd edition. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010. OCLC 25410010.

Digital Humanities Questions and Answers. “Can you do TEI with students, for close reading?” Association for Computing in the Humanities. Accessed February 27, 2011. http://digitalhumanities.org/answers/topic/tei-encoding-for-close-reading.

Fairer, David. 2009. Organising Poetry: The Coleridge Circle, 1790-1798. New York: Oxford University Press. OCLC 294886679 ISBN: 978019929616.

Flanders, Julia. 2006. “The Women Writers Project: A Digital Anthology.” In Electronic Textual Editing, edited by Lou Burnard, Katherine O’Brien O’Keeffe, and John Unsworth, 138-149. New York: The Modern Language Association of America. OCLC 62134738.

Hockey, Susan. 2000. Electronic Texts in the Humanities: Principles and Practice. New York: Oxford University Press. OCLC 45485006.

“Laura’s Dream; or, The Moonlanders.” Spenser and the Tradition: English Poetry 1579-1830, edited by. David Hill Radcliffe. Accessed September 19, 2012. http://spenserians.cath.vt.edu/TextRecord.php?action=GET&textsid=37330.

McGann, Jerome. 2004. “Marking Texts of Many Dimensions.” In A Companion to Digital Humanities, edited by Ray Siemens, Susan Schreibman, and John Unsworth. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. Accessed February 28, 2011. http://www.digitalhumanities.org/companion/view?docId=blackwell/9781405103213/9781405103213.xml&chunk.id=ss1-3-4. OCLC 54500326.

—. 1998. The Poetics of Sensibility. New York, Oxford University Press. OCLC 830989291.

Melesina Trench Student Edition, edited by Kate Singer. Accessed July 15, 2012. http://www.mtholyoke.edu/courses/ksinger/trench/student_projects.html.

Myopia: A Visualization Tool in Support of Close Reading, edited by Manish Chaturvedi, Gerald Gannod, Laura Mandell, Helen Armstrong, and Eric Hodgson. Accessed July 15, 2012. http://www.users.muohio.edu/chaturm/MovieHost.html.

Piez, Wendell. 2010. “Towards Hermeneutic Markup.” Digital Humanities 2010 Conference, King’s College London. Accessed February 28, 2011. http://www.piez.org/wendell/papers/dh2010/index.html.

Poetry Visualization Tool, edited by Laura Mandell. Accessed February 28, 2011. http://wiki.tei-c.org/index.php/PoetryVisualizationTool.

Project Tango. University of Virginia. Accessed February 26, 2011. http://uvatango.wordpress.com/2010/08/28/introducing-project-tango-2/.

Robinson, Daniel. 2011. The Poetry of Mary Robinson: Form and Fame. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. OCLC 658811982.

Rudy, Jason. 2009. Electric Meters: Victorian Physiological Poetics. Athens, Ohio: Ohio State University Press. OCLC 286479053.

Schwartz, Barry and Kenneth Sharpe. 2010. Practical Wisdom: The Right Way to Do the Right Thing. New York: Riverhead Hardcover. OCLC 646111798.

Southey, Robert. The Collected Letters of Robert Southey. Part I: 1791-1797. Letter 2. Ed. Lynda Pratt. Romantic Circles. Accessed March 24, 2013. http://www.rc.umd.edu/editions/southey_letters/Part_One/XML/letterEEd.26.2.xml

TEI Consortium. 2012. TEI P5: Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange, edited by Lou Burnard and Syd Bauman. Version 2.1.0. Last updated June 17. N.p.: TEI Consortium. http://www.tei-c.org/release/doc/tei-p5-doc/en/html/index.html.

Van den Branden, Ron, Melissa Terras, and Edward Vanhoutte. TEI by Example. Accessed March 24, 2013. http://www.teibyexample.org

Virtual Humanities Lab. Brown University. Accessed February 26, 2011. http://www.brown.edu/Departments/Italian_Studies/vhl_new/.

The Walt Whitman Archive. Eds. Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price. Center for Digital Research in the Humanities, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Accessed March 24, 2013. http://www.whitmanarchive.org/

Willett, Perry. 2004. “Electronic Texts: Audiences and Purposes.” In A Companion to Digital Humanities, edited by Ray Siemens, Susan Schreibman, and John Unsworth. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. Accessed February 28, 2011. http://www.digitalhumanities.org/companion/view?docId=blackwell/9781405103213/9781405103213.xml&chunk.id=ss1-3-6. OCLC 54500326.

World of Dante, edited by Deborah Parker. University of Virginia. Accessed February 27, 2011. http://www.worldofdante.org/.

Zafrin, Vika. RolandHT. Dissertation. Accessed February 26, 2011. http://rolandht.org/.

About the Author

Kate Singer is an Assistant Professor in the English Department at Mount Holyoke College. She is the Pedagogies Editor at Romantic Circles and the editor of the student edition of Melesina Trench’s The Moonlanders. She has published articles on Percy Shelley and Maria Jane Jewsbury and is currently at work on a book entitled Against Sensibility: British Women Poets, Romantic Vacancy, and Skepticism.