I came to explore the wreck.

The words are purposes.

The words are maps.

I came to see the damage that was done

and the treasures that prevail.

-Adrienne Rich, “Diving Into the Wreck”(2013, 22)

Figure 1. The image above shows a writing prompt created by a first year writing student at CUNY for the intra-classroom writing exchange between Brooklyn and Queens College.

“I came to explore the wreck,” Adrienne Rich begins her poem, and tumbles to the depths of her questions about efficacy—of speaking, writing, and teaching—during a time when student activists shut down campuses across the country, striking for antiracist education policies from curriculum design to admissions. When, as instructors of writing at Queens College and Brooklyn College, CUNY, we realized that we’d independently assigned our first-year writing classrooms selections from Rich’s recently published archive of teaching materials, we knew that beyond reading and analyzing her writing exercises, syllabi, or notes, our students would need to produce an archive of teaching materials of their own. We wondered, what could the process of recording and collecting their own work teach our students about the archive itself?

Designed as a collaboration between our students, ourselves, and Adrienne Rich’s teaching materials from Basic Writing at City College, we created an intra-classroom writing exchange in Spring 2018 which drew on the recent publication, ‘What We Are Part Of’: Teaching at CUNY: 1968-1974, (Parts I & II), published by Lost & Found: the CUNY Poetics Document Initiative in 2013. The project involved a total of forty-nine students, twenty-five at Queens and twenty-four at Brooklyn; half of the twenty-four Brooklyn College students were in CUNY’s SEEK (Search For Education, Elevation, and Knowledge) Program. Working simultaneously with other primary documents circulating during Adrienne Rich’s time at CUNY, our classes used digital file-sharing technology to eventually create an archive of their own writings. While discussing that no archive is ever complete–that any written record is a reconstruction of a lived context–we approached the archive as an evolving and contingent pedagogical map. Adrienne Rich’s poem “Diving Into the Wreck” was an important locus for this conversation because of the ways we were able to evoke the poem in the classroom as a living archive in a critically contingent digital space such as PennSound. Both classes listened to audio recordings hosted on UPenn’s poetry archive, giving students the chance to hear a recording of Adrienne Rich reading “Diving into the Wreck” at Stanford in the 1970s. The resonance of the poem’s themes in our own classrooms emphasized how the archive is kept alive and determined by the spaces in which it is contained. Ultimately, this allowed students to envision themselves as doing the work of both institutional critique and self archiving.

Tracing the Archive through CUNY’s History of Teacher & Student Activism

Lost & Found: the CUNY Poetics Document Initiative, published by the Center for the Humanities at The Graduate Center, CUNY, publishes “extra-poetic” material such as correspondence, journals, notes, transcriptions of letters and syllabi and pedagogical residue related to New American Poetry. Lost & Found “finds” the archive in sites which concretely include personal and institutional collections, raw materials gathered by editors, in interviews with living writers and selections from their material records, documents which circulate among poets, scholars, educators and fans, and in recirculated volumes which find their homes in collections, in libraries and in the classroom. More abstractly, the project locates the archive in person-to-person contact, verbal and non-quantifiable exchange, affective registers and especially in friendship.

The extent to which the classroom and the archive are considered together in the Lost & Found project cannot be understated. The publication collects pedagogical materials from a generation of poet educators teaching at CUNY in the 1960s and ‘70s. The Center for Humanities curates suggested groupings on their website for contemporary educators engaged in the building of syllabi for courses across CUNY and beyond with themed collections such as “Feminist Practice and Writing”; “Teaching Pedagogies/Methodologies”; “Resistance”; “Friendship and Politics”; “Radical Poetics”; “Queer Poetics,” and more.

Series IV’s “What We Are Part Of”: Teaching at CUNY: 1968-1974, Adrienne Rich (Parts I & II), collects the material traces of poet Adrienne Rich’s teachings at City College, and the series’ pedagogical focus continues with Series VII’s publication of investigations into other CUNY poets and educators: June Jordan: ‘Life Studies,’ 1966-1976, Audre Lorde: I teach myself in outline, Notes, Journals, Syllabi, & an Excerpt from Deotha, and Toni Cade Bambara: “Realizing the Dream of a Black University” & Other Writings (Parts I & II).

In the volume we introduced to our CUNY classrooms, we discussed how the notes, syllabi, and writing assignments created by Adrienne Rich exist not only as a record of poetic inquiry and pedagogical theory that Rich engaged with while teaching at City College, but also as a testament to the relationships formed through Rich’s commitment to deploying the “classroom” as a performative space in which writing, protest, and embodied action intersected. In designing an assignment sequence of our own, we noted the contingency inherent to the notion of the “classroom” for Rich: with classes closed frequently during the period due to student strikes and institutional flux, letters exchanged in the mail and individual meetings off-campus became the learning environments for Rich’s composition students.

(Dis)Locating the Classroom

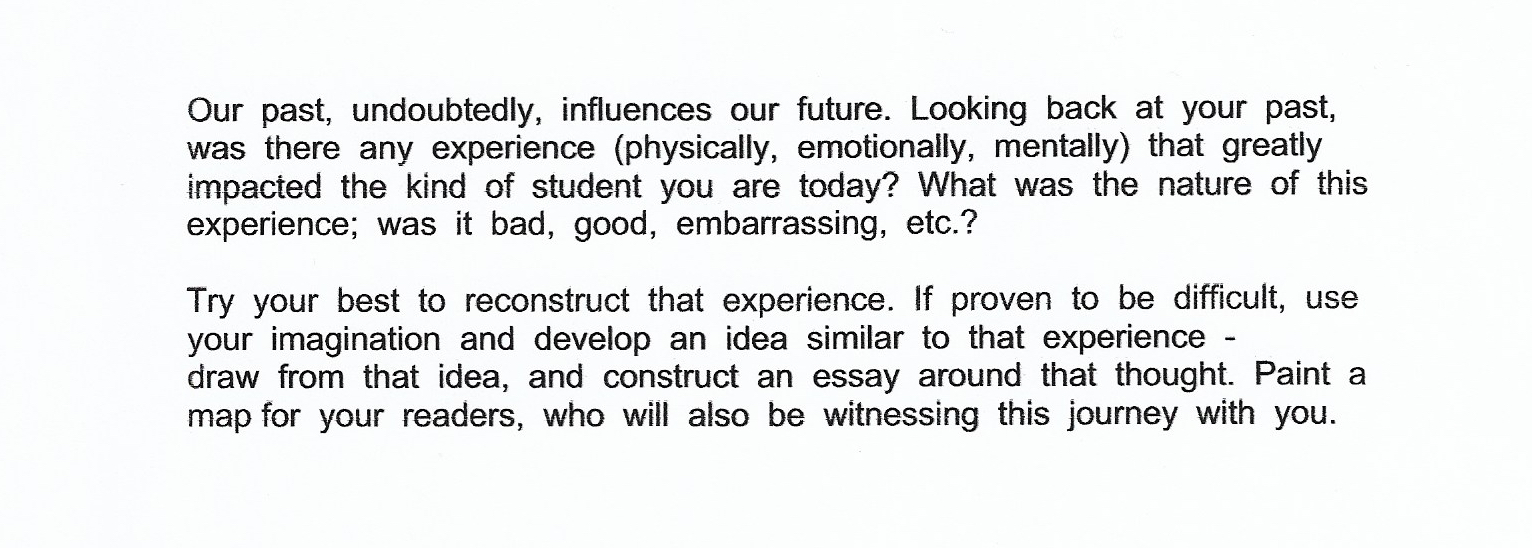

The ontological designation that comes with naming helps us understand that Rich often called the classroom into being through an act of naming alone: to declare an exchange a “classroom” makes it so, whether in a basement cafeteria or by way of the U.S. Postal Service. In fact, where Rich locates the classroom is as important as how and where she dislocates it, for to her the classroom is also “cell–unit–enclosed & enclosing space in which teacher & students are alone together / Can be a prison cell / commune / trap / junction–place of coming-together / torture chamber”(Rich 2013, vol. 1, 15). In our own writing exchange, the use of file-sharing technology facilitated the exchange of student writing outside and between our two classrooms. Each classroom was able to create a folder of student work in Dropbox that functioned as an online dossier. So while our classrooms were separated across two different physical campuses, our students’ works were collected in this temporary digital classroom.

Figure 2. Image from Adrienne Rich, “What We are Part Of”: Teaching at CUNY: 1968-1974 ed. Iemanjá Brown, Stefania Heim, erica kaufman, Kristin Moriah, Conor Tomás Reed, Talia Shalev and Wendy Tronrud, (Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative Series IV, 2013), 15.

In a memo on SEEK from 1969 or 1970 (exact date unknown), Rich goes on to suggest that the classroom is “also part of much bigger nationwide cultural revolution,” elaborated as such

a. movement for social change–break down false barriers of class & color to

make all education truly open to all people who want it b. movement for educational reform–such programs are surely going to effect changes in nature of teaching at all levels […]. (Rich 2013, vol. 1, 15).

To locate the classroom in the exchange between teacher and student and simultaneously in the nationwide cultural revolution is to bring politics to the classroom and the classroom to the world. Rich knew that to teach in the classroom was to engage the world from close proximity, a paradox because such engagement allowed her to tap into much more far-reaching social and political engagements than she’d found through poetry alone.

CUNY Students and the Archive

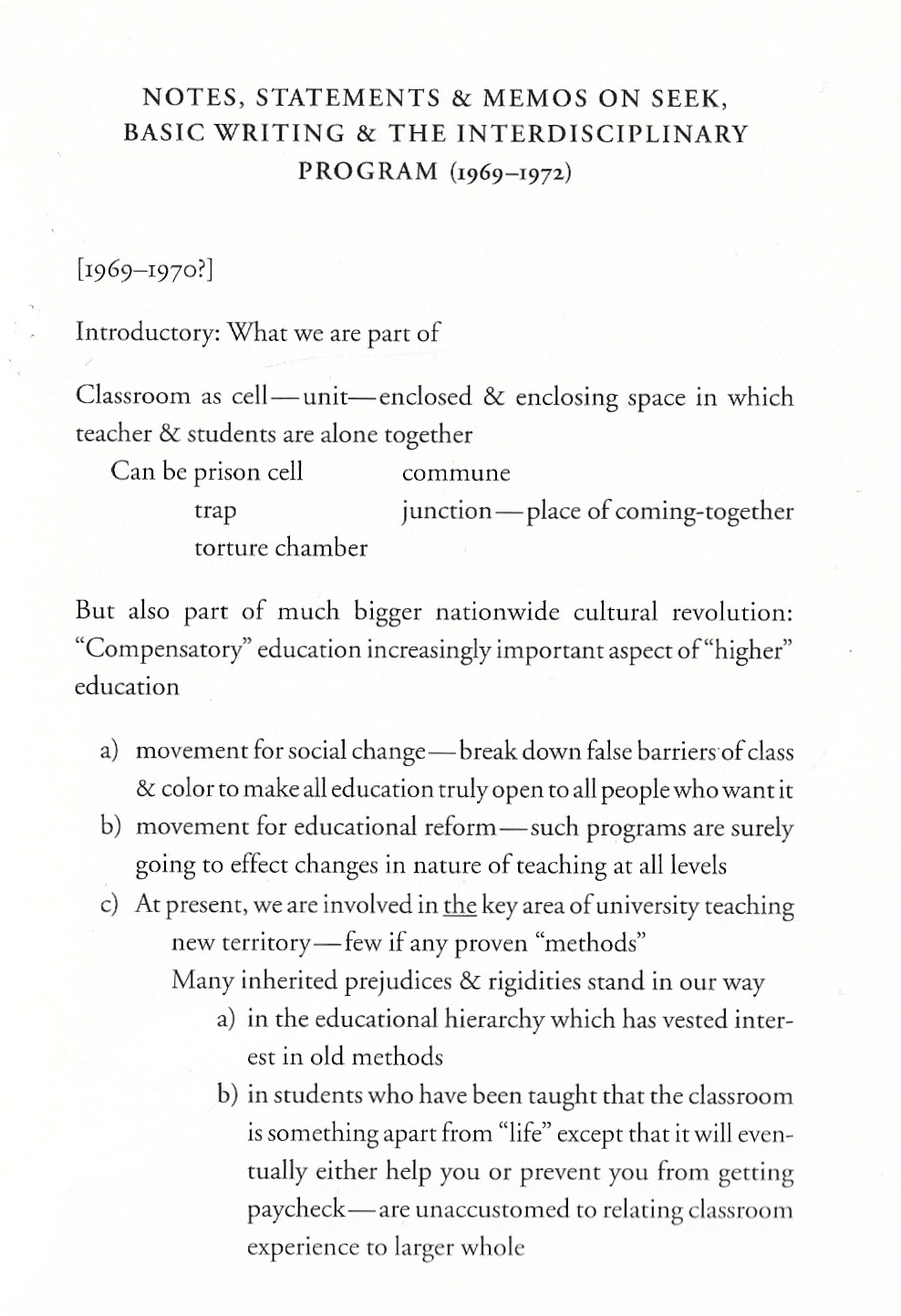

Focusing on Rich’s Writing Exercises, the first written component of the assignment sequence asked students to respond to a “Dream Course” exercise in which Rich prompted her students with the following:

Figure 3. Image from Adrienne Rich, “What We are Part Of”: Teaching at CUNY: 1968-1974 ed. Iemanjá Brown, Stefania Heim, erica kaufman, Kristin Moriah, Conor Tomás Reed, Talia Shalev, and Wendy Tronrud, (Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative Series IV, 2013), 7–8.

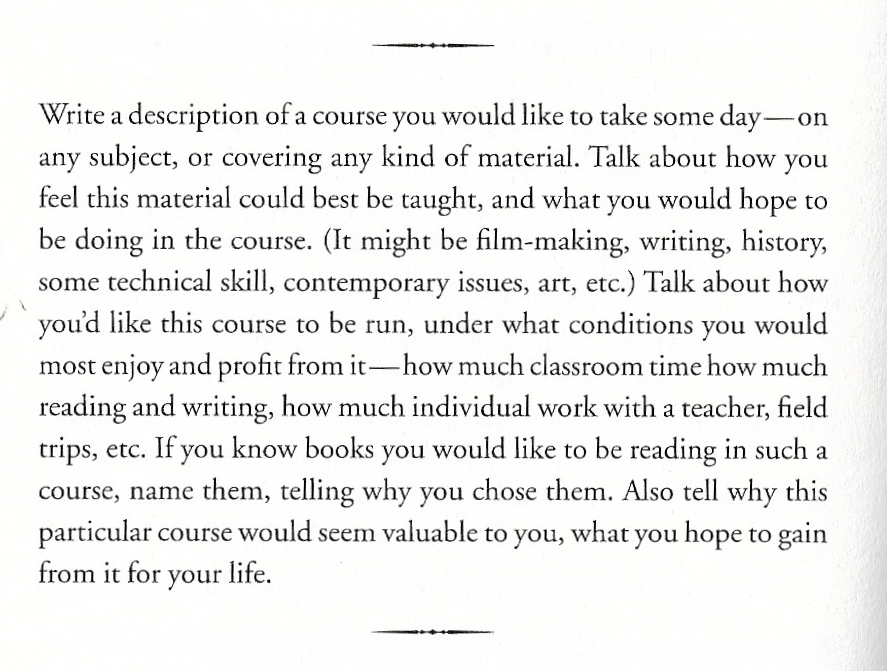

This first part of the assignment sequence asks students to put themselves in Rich’s classroom and imagine how the stakes of writing changed when the campus was transformed by protests. Our students were asked to read the “5 Demands” distributed in 1969 by a group of Black and Puerto Rican students at City College asking for equal representation and anti-racist admissions processes, as well as flyers, pamphlets, and notes that circulated across CUNY. Some of these materials can be found in the CUNY Digital History Archive, an online archive that collects digitized materials from CUNY’s history beginning in 1847 with the creation of the Free Academy in New York City and continuing to the present moment. To help students conceptualize their relationship to wider CUNY history, the CDHA offers a rich entry into the history of CUNY’s infrastructure, policies, and impact as a public institution, a history that implicates each student and determines their experience of education in the present. For instance, in order to access the “5 Demands,” students had to locate a link titled the “Creation of CUNY–Open Admissions Struggle” from a longer timeline, which ushered them to a page presenting wider archival materials from the late 1960s (oral histories, articles from student newspapers, and faculty memos). The CDHA’s Project History, which we also explored in the classroom setting, emphasizes that the CHDA emerged out of “gaps in the knowledge of CUNY faculty, students, staff, and alumni about that history,” a mission that resonated with our class’ focus on the archive as a means of generating engagement in the present with activism in the past.

Figure 4. Unknown, “Five Demands,” CUNY Digital History Archive, accessed September 26, 2018, http://cdha.cuny.edu/items/show/6952.

The next component of the assignment sequence had students compose their own writing prompts to be exchanged through the same Dropbox folder with a student at a different campus. Giving students the option to use the Dream Course they designed as inspiration for their exercise, we randomly assigned partners to students at Queens and Brooklyn Colleges. Two weeks later, after our students received their completed assignments, each class discussed their initial reactions to their partners’ responses and to the assignment sequence more broadly. Finally, our students reflected on their experience on their own and turned in a portfolio of the whole exchange, including a final reflection essay.

Documenting the Present

The exchange took place in a dialogic space in which students used their own assignment to deepen their understanding of Adrienne Rich’s pedagogy as emerging out of a moment when students were calling their education into question. After discussing the “5 Demands,” current Brooklyn and Queens students prompted their partners to speak about contemporary debates including discussions around tuition-free higher education. One student wrote to his partner:

In asking each other to use writing as means of interrogating the wider education system in their current moment, these students performed—and, in turn, affirmed—continuities between the historical conditions of Rich’s archive and the present moment. Linking student activism in the late 1960s to debates around Free Tuition at CUNY in early 2018, another student used the assignment to prompt questions about education and access:

Adrienne Rich’s Writing Exercises are opportunities for “reflection and action,” each assignment prompting students to tease out a “relationship to his [her/their] world, to his identity, to his sense of time and space, his trust in and suspicion of others, his ways of identifying others” (Rich 2013, vol. 1, 30) By designing their own writing prompts and then documenting the unfolding of an epistolary exchange, students came to a new way of conceiving of how participants in a classroom can build, envision, and also leave a record of the work that can move beyond the space and time of a single classroom.

Remarking on the experience of working with partners they have never met in person, a student at Brooklyn College observed that the structure of the assignment performs the process of community building and activism: “[The exchange] could be seen as a performance from Adrienne Rich’s notes on teaching…it could resemble the strike from the 70s and us having to always engage even with students we have not interacted with.” During the university-wide strike, solidarity meant connecting students from different CUNY institutions through a circulation of flyers, memos, and other written material; community was created through shared embodied demonstrations and exchanges across CUNY’s disparate campuses. As this student points out, this project forged connections between students from Queens and Brooklyn, which helped students feel embedded in CUNY, a public university comprised of twenty-five campuses across New York City’s five boroughs. Now as the complexity of our students’ exchange is embodied in—and reduced to—a folder of written documents, our students experienced how the archive is always incomplete in so far as it is only a fragment of a dynamic and living context; furthermore, the archive is always changing as it is part of an ongoing dialogue between the moment of its creation and the work it inspires today.

Next Steps

When we envision future iterations of this assignment, we realize we as instructors need to account for how the habits and codes we used to relate to students influenced the structure of the exchange. As one student suggests, allowing students to contact each other on their own terms—rather than through the instructors—would emphasize the importance of writing for one another rather than depending on the instructors’ authority. Beyond putting students in direct contact with one another in both public and private platforms for exchange, we conceptualize a means of engaging a wider public by collaborating more directly with existing digital platforms such as Lost & Found, CDHA, and PennSound. Since these public archives served as key pedagogical material and framing devices for students, we envision the next steps of this project as not just engaging with but contributing to their form and content. Projects that allow students to engage with the historical record through a practice of self-archiving challenge us to restructure existing hierarchies and rethink where and how learning takes place. By envisioning a type of study rooted in investigating and enacting the process of building an archive, this project produces an immaterial space within the university where students shift the power and become the interlocutors for each other.

It is in this not-yet-mediated space of connectivity and exchange that we were able to honor and continue the work of CUNY’s student-activists; it is here that we can build new archives of learning in and beyond the classroom, to “reexamine all that we’ve been doing, try untested things, put ourselves on the line, be willing to take risks” (Rich 2013, vol. 1, 16).