Introduction

The faculty development OER workshop is one of the most important, yet little-researched, links in the chain of adoption of open resources on campus. Most of the models that exist acknowledge the importance of concept learning for instructors encountering terms such as OER, ZTC, and open pedagogy for the first time. Moreover, teaching faculty about best practices in fair use and Creative Commons licensing—a related field—has a trickle-down effect to undergraduates. One way to achieve familiarity with open education is through hands-on learning, where instructors model examining and converting course materials to open or zero-cost and abiding by U.S. copyright law.

The digital game-based module in this case study was created as an alternative to the traditional workshop, to meet the needs of instructors as observed after several years of an OER initiative. It gives the users an opportunity to be active participants in a multimedia narrative and provides them with the flexibility of an asynchronous, iterative assignment. It also bases itself in scenario-based learning—problem-centered instructional solutions, which complement and cement the more straightforward directional learning in the regular faculty workshop. And, as a program made with a relatively uncomplicated open-source tool, it provides an attractive use case for both faculty and students.

The OER Faculty Development Workshop: Going Digital, Going Multimodal

The workshop in OER for faculty has not yet emerged as a subject of research, although a few on-campus initiatives have presented their versions, explaining decisions around context and organization. At a base level, the class primarily focuses on certain topics germane to the field: what are open resources and open education in general, what is meant by zero textbook cost, how do open licenses work, why follow best practices when pursuing free content, and how do instructors follow accessibility guidelines. Practice activities involve faculty participants searching for materials to replace assigned readings or, if the initiative is grounded in goal-based learning, determining the course objectives and the kinds of resources required to meet them. More than a workshop, this scope of subjects suggests a training program designed for specialist-facilitated, hands-on learning. However, given the relative novelty of the twenty-year-old field, no set rules exist and no single model prevails.

Several teaching bodies have seized upon the potential of the OER workshop to be taught remotely. In 2017, the City University of New York (CUNY) was awarded a $4 million package as part of a Scale Up! OER grant “to establish, sustain and enhance new and ongoing OER initiatives throughout CUNY” (CUNY Libraries 2017). Most of the work of converting a class to open involves searching across multiple databases, and variable concerns arise depending on the instructor’s discipline. The nature of instruction, even at these online-optimized institutions, thus remains of necessity hybrid, combining asynchronous content delivery with a synchronous mode for live discussion and troubleshooting. The possibility to take such courses remotely and for free has added convenience and flexibility; their parallel emergence at public commuter colleges in the CUNY and the Washington State Community college systems has been no accident.

In 2017, Lehman College-CUNY Director of Online Learning Olena Zhadko and Susan Ko, Director of Faculty Development at the NYU School of Professional Studies, developed an asynchronous, online faculty OER workshop to be offered for a two-week period several times during the year. The mini-course, designed for incorporation into the Blackboard LMS, scaffolds understanding of OERs through a module-based system, based on a tripartite organization of defining, finding, and integrating OER, as well as a discussion forum. The learners are asked to think about how open fits into their teaching and articulate their rationale for selecting a specific OER. Their final project in the workshop consists of a list of course materials replaced by open or zero-cost equivalents, with justification and description of intended use: adoption, adaptation, or creation. The library department at Lehman College has an accompanying final assignment for hands-on practice, which tests participants’ ability to link to websites, images, and video, apply attribution, and choose Creative Commons licenses (Cohen 2018).

Simultaneously with Lehman, the Washington State Board for Technical and Community Colleges—the creator of the Open Attribution Builder—developed a free, self-paced course made up of ten modules, including one on accessibility and a reflection on “Why OER Matters.” The website likewise includes “Personal Journeys Using OER,” a series of videos by on-campus practitioners. This version appears less hands-on yet also more personal than Lehman’s, emphasizing the human element of course conversions. It co-exists in a face-to-face format, offered over a two-week period at set points throughout the academic year. These inroads in digital education have opened up the possibility of yet more interactive ways for faculty to engage with the material in concert with the existing learning structure.

Creating a New Mode for the OER Workshop at Baruch College

The Baruch College-CUNY Center for Teaching and Learning joined the OER initiative the same year as Lehman and created an in-person faculty seminar accompanied by a set of slides since made publicly available on the Center’s OER pedagogy site. Baruch’s seminar, conducted in a mix of presentation and workshop elements, features backward course design (What outcomes am I looking for? How will I measure if these outcomes have been achieved?) as well as choice of platform (mainly between the Blackboard LMS and the proprietary, though open, WordPress site Blogs@Baruch). The most recent addition to the topics covered in the workshop have been open-source digital tools (Hypothes.is, StoryMap JS, Timeline JS, Voyant, and Twine), which are simple to use and versatile enough to create OERs for both teaching demonstrations and final assignments, i.e. teacher- or student-led work.

In 2019, on the suggestion of Center for Teaching and Learning Director Allison Lehr Samuels, I began creating a future addition to the workshop. In the spirit of providing opportunities for faculty to educate themselves about OER and related topics, the game, like the slides, was to be made openly available on the TeachOER website and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license (CC-BY-SA). Four goals for this project had materialized: (a) showcasing one of the digital tools, (b) adding another mode to the regular workshop to cater to different kinds of learners, (c) creating a fully asynchronous engagement experience with the workshop, which could also serve as review material, and (d) incorporating recurrent questions that had come from workshop participants for the past three years of the OER initiative.

The technology to carry out these diverse functions had to align with the Center’s principles of using open-source tools to support interactive digital solutions whenever possible. The college had already delved into creating single-player digital training with the 2009 Interactive Guide to Producing Copyrighted Media, developed by Baruch’s Computing and Technology Center and Kognito Interactive, a paid tool used for health simulations, owned and managed by college alumni. The experience took the user through an interactive maze consisting of various copyright and fair-use related situations drawing on such resources as U.S. copyright law, copyright guidelines for CUNY libraries, and public domain information. While this work was produced before any of today’s more common open-source tools and predated the state grant-funded initiative by several years, the Baruch library’s concern for adhering to best practices in decisions around intellectual property has been behind much of its OER programming as well.

The ultimate decision to make the new OER faculty workshop model with Twine, a non-linear, interactive storytelling tool for making single-player games based on decision-making, was grounded in Baruch’s longtime support for classroom technology as well as the Center for Teaching and Learning’s embrace of game-based pedagogy. According to the Center’s team,

The prevailing theory is that games enhance and mobilize internal desires and motivations for learning…[W]hen the rules of a game are tailored around learning outcomes, students are self-motivated to learn in order to ‘win’. Role-playing games in particular have been shown to increase student engagement and motivation to read, enhance persuasive writing and speaking, and increase critical and analytical thinking. (Baruch College CTL 2020)

Pedagogy games have in fact been shown to support classroom learning and stimulate greater engagement from students (Clark 2016; Gross 2007; Hamari, Koivisto, and Sarsa 2014). Internationally renowned game designer Jane McGonigal points out the salutary effect of games on students who experience the “satisfactions of achievement and mastery" (McGonigal 2016, 231). And a 2012 study by the Mathematics Education Research Journal showed 93% of class time was spent on task when using game-based learning, compared to only 72% without it (Bragg 2012). As the anti-rote memorization approach, game-playing is directly associated with active learning and has been a part of a general pedagogical shift towards fostering creativity by working through challenges and coming up with innovative solutions (Cheka-Romero and Gómez 2018; Lameras et al. 2015).

The Baruch CTL, already experienced in active learning practices, therefore considered the gaming approach optimal for the dual task of creating an alternative mode for faculty instruction and modeling new teaching techniques. And, with the target audience being the college’s largely contingent and overextended faculty, the team’s hope was that this exercise’s immersive approach would provide a high engagement—as well as an edutainment—quotient.

Twine and Digital Pedagogy

“Games should be created by everyone” is a motto that Chris Klimas, the creator of Twine, abides by in his work (Klimas 2020). The award-winning, Baltimore-based web developer and game designer published his text-authoring tool in 2009. The target audience was writers, and the experience of creating with Twine was meant to resemble a brainstorming exercise. Paying tribute to this legacy, its home page, www.twinery.org, to this day represents a corkboard with multi-colored notes attached to it with pushpins—a working surface of inspiration.

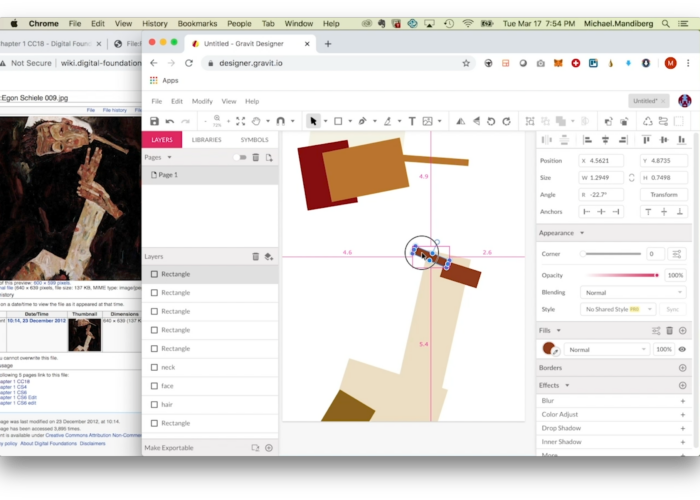

Passages in Twine’s editor interface appear in a simple, visual flowchart, a map of text nodes connected by arrows, to be filled out, then moved and rearranged at will. The starting point is a single node, and new ones are made when a user encloses the name of another passage in double brackets to continue the story. The scripting does not require any programming experience, although basic HTML skills are needed to change the style sheet and embed images, audio, and video. These technical features add up to a flexible, user-friendly tool with a low barrier to uptake, as well as quick connection capabilities due to its text-based nature. Scholar Anastasia Salter (2016) explains that an additional strength of Twine is its deregulated publication process, meaning that games can be distributed as quickly as they are created—unlike most products of subscription-based gaming websites, which go through an extensive review process before they can go live. This affordance of the open-source tool has also encouraged a greater immediacy and unselfconsciousness of the products made with it, as will be discussed later.

The main vehicle for moving through a Twine game has traditionally been the decision made by the user at the end of each passage between two or three options, each leading to a different fork in the narrative (occasionally, for the purposes of simply proceeding with the story, there may be just one choice). The origins of this decision-tree setup can be traced to “Choose Your Own Adventure,” a series of interactive fiction created in the 1970s by Edward Packard. Klimas (2020) fondly remembers devouring the CYOA books during regular visits to the public library and, later on, trying to “repurpose the genre for something more adult.” A manual on Twine for which Klimas served as the technical editor has recommendations for strong character arcs and narrative devices such as gifts and secret powers (Ford 2016). The author, who envisioned games like Dungeons and Dragons in book form, has since seen his stripped-down writing tool take on a superhero’s cloak—many of those using Twine build role-playing games that feature fighting fantasies. Another influence was hypertext in early Macs and the culture of object-oriented programming in graphical environments.

In a surprising development, yet one that its creator has heartily welcomed, the indie gaming community originally put Twine on the map in 2012–13, crafting a whole body of “vignette” stories with messages that are often unsettling or subversive. In a field dominated by males, its association with female voices and the experience of queer and marginalized groups has lasted to this day (Harvey 2014). Titles made with Twine range from the offbeat Cat Petting Simulator to 2014’s The Depression Quest, a work initially controversial for its very existence as a “game” yet now hailed for raising awareness of clinical depression by including crossed-out “non-choices”—regular actions impossible for someone afflicted with the condition. Salter (2016) refers to this feature as “metaphors of limitations” and praises the power of Twine’s economy of means as helpful for conveying emotion and raising awareness of mental health issues. (She also stresses that it is one of the few vehicles for games with non-mainstream/taboo subjects.)

While Twine has largely flown under the radar, the darling of a niche creative community, greater exposure has recently come to it from popular artistic culture—and, to some extent, the educational environment. The new-media artist Porpentine Charity Heartscape, whose unsettling, subversive games are made largely with the tool, had her works, With Those We Love Alive and howling dogs, featured in the 2017 Whitney Biennial (Klimas 2017). The following year, Charlie Brooker, the creator of the interactive Netflix film Black Mirror: Bandersnatch (2018) announced that its hundred-plus page script was written entirely in Twine (Aggarwal 2019). Around the same time, instructors began discussing their own teaching projects made with the tool and posting assignments made for humanities courses on the open web (McGrath 2019) (McCall 2017, 2019) although the practice remains limited to select classes by the enthusiastic few.

Salter credits Twine’s orientation toward the agency of the main character and lack of a peer-reviewed publishing model with its rising prominence: “Compared to the intensive team-based productions of 2D and 3D games, text-based games continue to offer a space for individual production.” In an industry known for technological extravagance, Twine is the plucky underdog that can achieve inspired—and pedagogically sound—results within a surprising economy of means.

The Baruch Twine Game: Scenario-Based Learning in a “CYOA” Format

According to its reviewers, Twine’s greatest affordance is that it deepens understanding and engagement through exploring alternatives. The Old Régime and the OER Revolution game also aims to mimic the branching, decision-making process of selecting the materials for a class: why and how should faculty abide by best practices? What are the consequences and trade-offs of certain decisions one makes in choosing freely distributed over proprietary copies—for legal repercussions, plain peace of mind, pedagogical freedom? And, more generally, why should instructors care about these issues if they do not yet teach with open resources? The title, juxtaposing “the old ways” and the “OER turn,” alludes to the main character’s specialization: in the game, “you” are a professor of French history. Yet more broadly, it references the pedagogical transformation involved in switching to open resources, which cover a wide range of mediums and modalities and involve not just a replacement of materials but also an examination of the way one teaches.

The decision that launches the game is not to teach in the usual way, as the introduction says of the main character:

You have always struggled with how unsatisfactory and expensive textbooks on the subject are…Given that your students come from so many diverse and international backgrounds, you wish there were some texts that talked more at length about their histories. (Tsan 2020)

As explained in a footnote, the prototype for this hero is Helmut Loeffler, a professor in the History Department of Queensborough Community College, CUNY, who authored a text, Introduction to Ancient Civilizations (2015), with a small grant, creating a book that understandably eschewed timelines, charts, or illustrations (Loeffler 2019). The non-fiction aspect of this “origin story” of the interactive fiction game was intentional, since the overarching goal of any faculty OER workshop is to inspire by actual example.

The Old Régime and the OER Revolution game follows Scenario-Based Learning (SBL), a popular instructional strategy in online training. In this approach, facilitators use situations close to ones that might come up and introduce applicable problems, to which the participants try to figure out the answers. Because SBL is grounded in the premise of applicability for the learners, the role-playing game aspect of many Twine products does not apply here. There are no magic friends, secret weapons or helpful gifts picked up, and the experience stays in the realm of the believable. (However, more than one aside, such as the French history professor’s waxing eloquent over a War and Peace passage she is choosing for her open syllabus, or the character of a curmudgeonly faculty member determined to resist the incursions of OER content, have been included for the purposes of levity or edutainment).

The single-player Old Régime game was designed to be non-competitive and low-stakes, a “game” in the sense of an adventure rather than a quest that results in “winning” or “losing.” In this sense, it is inspired by Jane McGonigal’s assertion that “good game developers know that the emotional experience itself is the reward” (McGonigal 2011, 244). Like most Twine tutorials created for learning and instruction, it follows the simple mode of SBL, “used to validate the learner’s recall and basic comprehension” and “good for basic problem solving” (Pandey 2018). In a similar vein, a Twine game recently made at Hostos Community College, CUNY, “encourages college-level English Language Learners to practice grammar concepts as they play the game narrative” (Lyons and Lundberg 2018). Making the wrong choice of several options sends the user back to do the exercise again until they get it right and can proceed with a visit to the Metropolitan College of Art (Met)—a relatable exercise for Hostos ELL students who frequently go to the real-world Met on field trips. The Old Régime aims for a more branching narrative, since, due to variations in the availability and permissions of course material, the choices taken by an instructor can only sometimes be classified in the right or wrong category.

While The Old Régime does not frequently correct the user’s choices, it has built-in capabilities for addressing decisions that may result in an impasse. If the answer is blatantly incorrect (“copy a 1992 book in its entirety and distribute the PDF to your class”) or fraught (“embed the YouTube link to a culinary video directly in your course website”), it leads to an “explainer”—a tactic common to Twine narratives where the user can explore links embedded within the body of the text for extra information and then go back to the main narrative. The explainers used in the game align almost exactly with the principal concepts being communicated: OER, zero-cost materials, saving money on textbooks, copyright/fair use doctrine, Creative Commons licenses, and open pedagogy (see Figure 2). Since the premise is that participants go through this experience to learn rather than be tested on their knowledge, the game aims to take them through the real-life consequences of certain actions. For instance, one storyline explains that, in a rare case, you may receive a DMCA (Digital Millennium Copyright Act) notice to take down illegal digital content, and another shows how always having a rationale for why you are obeying the fair use doctrine in a specific case might save trouble and keep you on the right side of copyright law.

Scenario-based learning is often explained in the context of scaffolding the skills being taught to the learners (Clark and Mayer 2012). As the cognitive psychologist Jerome Bruner, who first coined the term while inspired by Lev Vygotsky’s Zone of Promixal Development theory, has posited, the goal here is to provide a series of instructional techniques and support to increase the learner’s understanding, with the end result of increased independence (Wood, Bruner, and Ross 1976). The Old Régime begins with an explanation of the main concepts in the open community, then goes on to offer the user the choice of working through a trio of syllabi types: (a) a traditional list of copyrighted resources, (b) a set of zero-cost multimedia resources, some of them of questionable provenance, and (c) a non-traditional syllabus focused on assignment creation, i.e. open pedagogy (a section paying tribute to recent developments and publications in the field). The issues within escalate in terms of complexity, from questions such as “Can I distribute a PDF I got off the Internet?” to “What digital tools can students use to create multimedia assignments?” While faculty can choose which syllabus to start with, depending on their interests and background, as well as go back and forth between the syllabi, there is a natural progression built into the game from less to more open permissions.

Although most Twine games are text-based, with visuals, if any, used for illustrative purposes, the images, audio, and video in The Old Régime serve an integral purpose: to demonstrate the variety of resources—and issues—a faculty member might come across in their OER course-conversion journey. One page, for instance, features a poster for the Andrzej Wajda-directed film Danton (1983) on Wikipedia, discussed in the game as an example of a fair-use argument (according to the Wikimedia Foundation, the commercial poster had to be used on the website since it was the only available visual of the film). Even on pages where the image cited is not directly related to an argument over openness, the purpose of including it is to reinforce correct attribution practices—each picture in the game comes from Wikimedia Commons and carries either a public domain or a Creative Commons license. A visualized broken link message reinforces a discussion of permanence, and a video from the New York Times’ cooking section is embedded next to a paragraph about the potential dangers of “link rot.”

In recognition of the range of curricular decisions available to faculty, the game is signposted throughout with a system of symbols that explain to the learner whether they are being told about a resource that is fully open (green O—“this resource can be used, modified and redistributed freely”), open with restrictions (yellow O—“look out for restrictions on modification and/or redistribution”), and zero textbook cost (yellow Z—“look out for restrictions on use, modification and/or redistribution”). This iconography was originally developed by CTL staff member Pamela Thielman to classify the teaching materials posted on the TeachOER website, as well as to appeal to audiovisual learners, in a sustained commitment to multimodality.

Reflections and Potential Applications

The Old Régime and the OER Revolution game had its planned launch during the Spring 2021 semester OER faculty development workshop, running remotely for the first time with two sections of fourteen participants in total. Due to other priorities that emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic, this initiative did not involve gathering feedback on the game. Moreover, the small sample size has made it difficult to draw causal inferences between game playing and seminar completion. Nonetheless, the anecdotal evidence from having faculty participants play the game—for many, their first encounter with the topic of open-source education—has been positive. The number of questions and points of confusion that the seminar leaders get—especially about OER vs. ZTC and where to look for open-source images—has lessened significantly. One area that needed clarification from a number of seminar participants is the meaning of a Creative Commons license and the mechanism for creating one. This observation is being used to create an update (i.e. a sub-scenario) to the game that focuses specifically on these questions.

Because of the comparative ease of screen sharing and the availability of virtual help, Baruch’s CTL has launched a concomitant initiative to encourage faculty to create their own assignments made with open-source tools. Despite the predictable roadblocks to this effort in pandemic times, it has met with success so far: several faculty members have authored interactive course resources predicated on input from students, which they are currently using to teach their classes. Twine has not featured among their chosen platforms so far, most likely because it still enjoys less visibility on an institutional level and is also perceived as a “more involved” and time-consuming choice. Knight Lab tools, which do not require CSS stylesheet language, especially StoryMap JS, are currently a bigger draw among Baruch instructors. Although more hands-on tutorials are needed to dispel the understandable hesitation many faculty members still feel about creating their own resources, the ensemble of these efforts has gradually led to a greater engagement with, and appreciation of, OER on campus.

Feedback on the game from instructional designers and Baruch faculty who playtested the game during the 2020 Baruch OER Faculty Showcase, featured in Figures 7–9, has been used to edit the current version for greater clarity and playability. A more robust set of instructions is being created and guidelines for helping players navigate through all three scenarios developed. Moreover, the game developer has set up an apparatus with learning objectives and specific questions to better target faculty engagement. A “how we made it” section and detailed instructions for making one’s own basic Twine resource will eventually accompany the game: information on where to find tutorials, what some examples with the best interactivity/greatest emotional impact are, and how the game can be hosted with campus technology. Such a content-based approach in the supplementary material means to combine subject expertise and instructional design, taking its example from openly published resources on making history simulation games and brainstorming creative writing with Twine (McCall 2016, 2017, and 2019; McGrath 2019). More educational solutions—using Twine for process modeling in entrepreneurship classes, to consider alternate plot twists in literature, or to follow scientific processes—are being considered.

These efforts are taking place alongside promising developments in Twine itself. Emily Christina Murphy and Lai-Tze Fan have announced they are assembling EnTwine: A Critical and Creative Companion to Teaching with Twine, a proposed companion to the new and invaluable Twining: Critical and Creative Approaches to Hypertext Narratives (2021) by Anastasia Salter and Stuart Moulthrop, with the latter published on Amherst College Press’s OER platform. In the past year, Chris Klimas has also released a new story format, Chapbook, which makes it easier to work with multimedia and create and play mobile-friendly games (The Old Régime was written in the default format, Harlowe, authored by Leon Arnott). As stated in a presentation to the Interactive Fiction Technology Foundation’s annual event, NarraScope, the Twine team hopes to add a collaborative authorship function in the future (Klimas 2019), making the tool a natural choice not just for assignment creation, but also for in-class work, either in the face-in-face or asynchronous format.

Conclusion

Instructional designers, pedagogy specialists, and librarians who wish to create their own faculty workshop for teaching about open resources are encouraged to think about building both asynchronous and interactive content into their programming. The changing content of the open education field highlights the importance of providing materials in flexible ways that permit add-ons and variations. Easy-to-use open-source tools constitute a convenient and pedagogically sound resource for the faculty workshop. Twine, with its decision-tree setup and built-in interactivity, presents one possible solution to faculty handling their scenario-based learning independently and remotely alongside other face-to-face or synchronous modalities and asynchronous discussions. The other affordance of “teaching OER with OERs” is the example it provides to faculty who might introduce tools such as Twine to their own classes, creating assignments and perpetuating a culture of best practices in online publishing. The ongoing improvements in the technology suggest that gaming pedagogy can indeed become the vehicle for teaching about openness while promoting active learning and student initiative. However, a concerted initiative that combines instructional design and subject-specific pedagogy is needed to make this vision a reality.