Wikipedia has become a popular educational tool over the last two decades, especially in the fields of composition and writing studies. The online encyclopedia’s “anyone-can-edit” ethos emphasizes the collective production of informative writing for public audiences, and instructors have found that they can use it to teach students about writing processes such as citation, collaboration, drafting, editing, research, and revision, in addition to stressing topics such as audience, tone, and voice (Purdy 2009, 2010; Hood 2009; Vetter, McDowell, and Stewart 2019; Xing and Vetter 2020). Composition courses that use Wikipedia have thus begun to follow a similar pattern. Students examine Wikipedia’s history, examine the way its three content policies (Neutral point-of-view [NPOV], no original research, and verifiability) govern how entries are written and what research sources are cited, and discuss the advantages and limits of Wikipedia’s open and anonymous community of volunteer contributors. Then, as a final assignment, instructors often ask students to edit an existing Wikipedia entry or write their own. By contrast, instructors in fields like cultural studies, feminism, and postcolonialism foreground Wikipedia’s social inequalities by asking students to examine how its largely white and male volunteer editors have resulted in the regrettable lack of topics about women and people of color (Edwards 2015; Pratesi, Miller, and Sutton 2019; Rotramel, Parmer, and Oliveira 2019; Montez 2017; Koh and Risam n.d.). When they ask students to edit or write Wikipedia entries, these instructors also invite students to focus on minority groups or underrepresented topics, thus transforming the typical final assignment into one that mirrors the Edit-A-Thons hosted by activist groups like Art + Feminism.

The socially conscious concerns that instructors in cultural studies, feminism, and postcolonialism have raised are compelling because they foreground Wikipedia’s power dynamics. When constructing my own first-year undergraduate writing course at the University of Virginia, then, I sought to combine these concerns with the general approach instructors in composition and writing studies are using. In the Fall 2019 iteration of my course, my students learned about topics like collaborative writing and citation, in addition to examining academic and journalistic articles about the encyclopedia’s racial and gender inequalities. The unit concluded with a two-day Edit-A-Thon focused on African American culture and history. The results seemed fabulous: my brilliant students produced almost 20,000 words on Wikipedia, and created four new entries—one about Harlem’s Frederick Douglass Book Center and three about various anti-slavery periodicals.[1] In their reflection papers, many conveyed that Edit-A-Thons could help minority groups and topics acquire greater visibility, and argued that the encyclopedia’s online format accelerates and democratizes knowledge production.

Yet, as an instructor, I felt that I had failed to sufficiently emphasize how Wikipedia’s content policies also played a role in producing the encyclopedia’s social inequalities. Although I had devoted a few classes to those policies, the approaches I adapted for my unit from the composition and the cultural studies fields meant my students only learned how to adopt those policies—not how to critically interrogate them. The articles we read also obscured how these policies relate to the encyclopedia’s social inequalities because scholars and journalists often conceptualize such inequalities in terms of proportion, describing how there is more or less information about this particular race or that particular gender (Lapowsky 2015; Cassano 2015; Ford 2011; Graham 2011; John 2011). Naturally, then, that’s how our students learn to frame the issue, too—especially when the Edit-A-Thons we organize for them focus on adding (or subtracting) content, rather than investigating how Wikipedia’s inequalities also occur due to the way the encyclopedia governs language. Similar observations have been raised by feminist instructors like Leigh Gruwell, who has found that Wikipedia’s policies “exclude and silence feminist ways of knowing and writing” and argued that current pedagogical models have not yet found ways to invoke Wikipedia critically (Gruwell 2015).[2]

What, then, might a pedagogical model that does invoke Wikipedia critically look like? I sought to respond to this question by creating a new learning goal for the Wikipedia unit in the Spring 2020 iteration of my course. This time around, I would continue to encourage my students to use Wikipedia’s content policies to deepen their understanding of the typical topics in a composition course, but I would also invite them to examine how those policies create—and then conceal—inequalities that occur at the linguistic level. In this particular unit, we concentrated on how various writers had used Wikipedia’s content policies to reinscribe white supremacy in an entry about UVa’s history. The unit concluded with an Edit-A-Thon where students conducted research on historical materials from UVa’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library to produce a Wikipedia page about the history of student activism at UVa. This approach did not yield the flashy, tweet-worthy results I saw in the Fall. But it is—to my mind—much more important, not only because it is influenced by postcolonial theorists such as Gayatri Spivak, who has demonstrated that neutrality or “objectivity” is impossible to achieve in language, but also because it prompted my students to discuss how language and politics shape, and are shaped by, each other. In the process, this approach also reminds instructors—especially in composition and writing studies—to recognize that it is impossible to teach writing decoupled from the politics of language. Indeed, Jiawei Xing and Matthew A. Vetter’s recent survey of 113 instructors who use Wikipedia in their classrooms reveals that they did so to develop their students’ digital communication, research, critical thinking, and writing skills, but only 40% of those instructors prompted their students to engage with the encyclopedia’s social inequalities as well (Xing and Vetter 2020). While the study’s participant pool is small and not all the instructors in that pool teach composition and writing courses, the results remain valuable because they suggest that current pedagogical models generally do not ask students to examine the social inequalities that Wikipedia’s content policies produce. This article therefore outlines an approach that I used to invite my students to explore the relationship between language and social inequalities on Wikipedia, with the hope that other instructors may improve upon, and then interweave, this approach into existing Wikipedia-based courses today.

Given that this introduction (and the argument that follows) stress a set of understudied issues in Wikipedia, however, my overall insistence that we should continue using Wikipedia in our classrooms may admittedly seem odd. Wouldn’t it make more sense, some might ask, to support those who have argued that we should stop using Wikipedia altogether? Perhaps—but I would have to be a fool to encourage my students to disavow an enormously popular online platform that is amassing knowledge at a faster rate than any other encyclopedia in history, averages roughly twenty billion views a month, and shows no signs of slowing down (“Wikimedia Statistics – All Wikis” n.d.). Like all large-scale projects, the encyclopedia contains problems—but, as instructors, we would do better to equip our students with the skills to address such problems when they arise. The pedagogical approach that I describe in this paper empowers our students to identify some problems directly embedded in Wikipedia’s linguistic structures, rather than studying demographic data about the encyclopedia alone. Only when these internal dynamics are grasped can the next generation then begin to truly reinvent one of the world’s most important platforms in the ways that they desire.

1. Wikipedia’s Neutrality Problem

Wikipedia’s three interdependent content policies—no original research, verifiability, and neutral point of view—are a rich opportunity for students to critically engage with the encyclopedia. Neutral point of view is the most non-negotiable policy of the three, and the Wikipedia community defines it as follows:

Neutral point of view (NPOV) … means representing fairly, proportionately, and, as far as possible, without editorial bias, all the significant views that have been published by reliable sources about the topic … [it means] carefully and critically analyzing a variety of reliable sources and then attempting to convey to the reader the information contained in them fairly, proportionally … including all verifiable points of view. (“Wikipedia: Neutral Point of View” 2020)

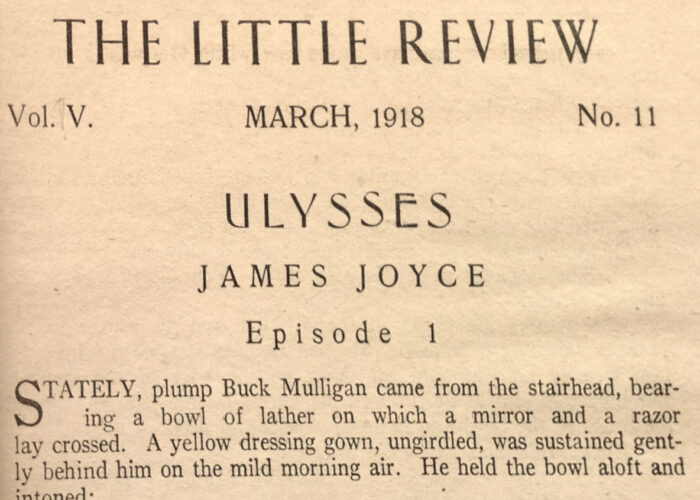

Brief guidelines like “avoid stating opinions as facts” and “prefer nonjudgmental language” (“Wikipedia: Neutral Point of View” 2020) follow this definition. My students in both semesters fixated on these points and the overall importance of eschewing “editorial bias” when engaging with NPOV for the first time—and for good reason. A writing style that seems to promise fact alone is particularly alluring to a generation who has grown up on fake news and photoshopped Instagram bodies. It is no surprise, then, that my students responded enthusiastically to the first writing exercise I assigned, which asks them to pick a quotidian object and describe it from what they understood to be a neutral point of view as defined by Wikipedia. The resulting pieces were well-written. When I ran my eyes over careful descriptions about lamps, pillows, and stuffed animals, I glimpsed what Purdy and the composition studies cadre have asserted: that writing for Wikipedia does, indeed, provoke students to write clearly and concisely, and pay closer attention to grammar and syntax.

Afterwards, however, I asked my students to consider the other part of NPOV’s definition: that the writer should proportionally articulate multiple perspectives about a topic (“Wikipedia: Neutral Point of View” 2020). A Wikipedia entry about our planet, for example, would include fringe theories claiming the Earth is flat—but a writer practicing NPOV would presumably ensure that these claims do not carry what Wikipedians describe as “undue weight” over the scientific sources which demonstrate that the Earth is round. Interestingly, the Wikipedia community’s weighing rhetoric associates the NPOV policy with the archetypal symbol of justice: the scales. Wikipedians do not merely summarize information. By adopting NPOV, they appear to summarize information in the fairest way. They weigh out different perspectives and, like Lady Justice, their insistence on avoiding editorial bias seems to ensure that they, too, are metaphorically “blindfolded” to maintain impartiality.

Yet, my students and I saw how NPOV’s “weighing” process, and Wikipedia’s broader claims to neutrality, quickly unraveled when we compared a Wikipedia entry to another scholarly text about the same subject. Comparing and contrasting texts is a standard pedagogical strategy, but the exercise—when raised in relation to Wikipedia—is often used to emphasize how encyclopedic language differs from fiction, news, or other writing genres, rather than provoking a critical engagement with Wikipedia’s content policies. In my Spring 2020 course, then, I shifted the purpose of this exercise. This time around, we compared and contrasted two documents—UVa’s Wikipedia page and Lisa Woolfork’s “‘This Class of Persons’: When UVa’s White Supremacist Past Meets Its Future”—to study the limits of Wikipedia’s NPOV policy.

Both documents construct two very different narratives to describe UVa’s history. My students and I discovered that their differences are most obvious when they discuss why Thomas Jefferson established UVa in Charlottesville, and the role that enslaved labor played in constructing the university:

| Wikipedia | Woolfork |

|---|---|

| In 1817, three Presidents (Jefferson, James Monroe, and James Madison) and Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court John Marshall joined 24 other dignitaries at a meeting held in the Mountain Top Tavern at Rockfish Gap. After some deliberation, they selected nearby Charlottesville as the site of the new University of Virginia. [24]. (“University of Virginia” 2020) | On August 1, 1818, the commissioners for the University of Virginia met at a tavern in the Rockfish Gap on the Blue Ridge. The assembled men had been charged to write a proposal … also known as the Rockfish Gap Report. … The commissioners were also committed to finding the ideal geographical location for this undertaking [the university]. Three choices were identified as the most propitious venues: Lexington in Rockbridge County, Staunton in Augusta County, and Central College (Charlottesville) in Albemarle County. … The deciding factor that led the commissioners to choose Albemarle County as the site for the university was exclusively its proximity to white people. The commissioners observed, “It was the degree of the centrality to the white population of the state which alone then constituted the important point of comparison between these places: and the board … are of the opinion that the central point of the white population of the state is nearer to the central college….” (Woolfork 2018, 99–100) |

| Like many of its peers, the university owned slaves who helped build the campus. They also served students and professors. The university’s first classes met on March 7, 1825. (“University of Virginia” 2020) | For the first fifty years of its existence, the university relied on enslaved labor in a variety of positions. In addition, enslaved workers were tasked to serve students personally. … Jefferson believed that allowing students to bring their personal slaves to college would be a corrosive influence. … [F]aculty members, however, and the university itself owned or leased enslaved people. (Woolfork 2018, 101) |

Table 1. Comparison of Wikipedia and Woolfork on why Thomas Jefferson established UVa in Charlottesville, and the role that enslaved labor played in constructing the university

Although the two Wikipedia extracts “avoid stating opinions as facts,” they expose how NPOV’s requirement that a writer weigh out different perspectives to represent all views “fairly, proportionately, and, as far as possible” is precisely where neutrality breaks down. In the first pair of extracts, the Wikipedia entry gives scant information about why Jefferson selected Charlottesville. Woolfork’s research, however, outlines that what contributors summarized as “some deliberation” was, in fact, a discussion about locating the university in a predominantly white area. The Wikipedia entry cites source number 24 to support the summary, but the link leads to a Shenandoah National Park guide that highlights Rockfish Gap’s location, instead of providing information about the meeting. Woolfork’s article, by contrast, carefully peruses the Rockfish Gap Report, which was produced in that meeting.

One could argue, as one of my students did, that perhaps Wikipedia’s contributors had not thought to investigate why Jefferson chose Charlottesville, and therefore did not know of the Rockfish Gap Report’s existence—and that is precisely the point. The Wikipedia entry’s inclusion of all three Presidents and the Chief Justice suggests that, when “weighing” different sources and pursuing a range of perspectives about the university’s history, previous contributors decided—whether knowingly or unconsciously—that describing who was at the meeting was a more important viewpoint. They fleshed out a particular strand of detail that would cement the university’s links to American nationalism, rather than inquire how and why Charlottesville was chosen. An entry that looks comprehensive, balanced, well-cited, and “neutral,” then, inevitably prioritizes certain types of information based on the information and the lines of inquiry its contributors choose to expand upon.

The second pair of extracts continue to reveal the fractures in the NPOV policy. Although Woolfork’s research reveals that the university used enslaved labor for the first 50 years, the only time the 10,000-word Wikipedia entry mentions slavery is buried within the three sentences I copied above, which undercuts NPOV’s claims to proportionality. Moreover, the first sentence carefully frames the university’s previous ownership of slaves as usual practice (“like many of its peers”). It is revealing that the sentence does not gaze, as it has done for the majority of the paragraph where this extract is located, on UVa alone—but expands outward to include all universities when conveying this specific fact about slavery. Interestingly, these facts about enslaved labor also come before the sentence about the university’s first day of classes. This means that the entry, which has so far proceeded in chronological fashion, suddenly experiences a temporal warp. It places the reader within the swing of the university’s academic life when it conveys that students and professors benefitted from enslaved labor, only to pull the reader backwards to the first day of classes in the next sentence, as though it were resetting the clock.

I want to stress that the purpose of this exercise was not to examine whether Woolfork’s article is “better” or “truer” than the Wikipedia entry, nor was it an opportunity to undercut the writers of either piece. Rather, the more complex concept my students grappled with was how the article and the entry demonstrate why the true/false—or neutral/biased—binaries that Wikipedia’s content policies rely on are themselves flawed. One could argue that both pieces about UVa are “true,” but the point is that they are slanted differently. The Wikipedia entry falls along an exclusively white axis, while Woolfork’s piece falls along multiple axes—Black and white—and demonstrates how both are actually intertwined due to the university’s reliance on enslaved labor. From a pedagogical standpoint, then, this exercise pushed my students in two areas often unexplored in Wikipedia assignments.

First, it demonstrated to my students that although phrases like “editorial bias” in Wikipedia’s NPOV guidelines presuppose an occasion where writing is impartial and unadulterated, such neutrality does not—and cannot—exist. Instructors in composition studies often ask students to practice NPOV writing for Wikipedia to improve their prose. This process, however, mistakenly conveys that neutrality is an adoptable position even though the comparative exercise I outlined above demonstrates neutrality’s impossibility.

Second, the comparative exercise also demonstrated to my students that Wikipedia’s inequalities occur at the linguistic level as much as the demographic level. Instructors in cultural studies frequently host Edit-A-Thons for their students to increase content about minority cultures and groups on Wikipedia, but this does not address the larger problem embedded in NPOV’s “weighing” of different perspectives. The guidelines state that Wikipedians must weigh perspectives proportionally—but determining what proportionality is to begin with is up to the contributors, as evinced by the two Wikipedia extracts I outlined. Every time a writer weighs different sources and perspectives to write an entry, what they are really doing is slanting their entry along certain axes of different angles, shapes, shades, and sizes. In the articles my students read, the most common axis Wikipedians use, whether knowingly or unconsciously, is one that centers white history, white involvement, and white readers. For example, as my students later discovered in Wikipedia’s “Talk” page for the entry about UVa, when two editors were discussing whether the university’s history of enslaved labor rather than its honor code should be mentioned in the entry’s lead, one editor claimed that the enslaved labor was not necessarily “the most critical information that readers need to know” (“University of Virginia” 2020).[3] Which readers? Who do Wikipedians have in mind when they use that phrase? In this instance, we see how “weighing” different perspectives not only leads one to elevate one piece of information over another, but also one type of reader over another.

As instructors, we need to raise these questions about audience, perspective, and voice in Wikipedia for our students. It is not so much that we have not covered these topics: we just haven’t sufficiently asked our students to engage with the social implications of these topics, like race (and, as Gruwell has said so cogently, gender). One way to begin doing so is by inflecting our pedagogical approaches with the discoveries in fields such as postcolonial studies and critical race studies. For example, my pedagogical emphasis on the impossibility of neutrality as I have outlined it above is partially indebted to critics like Gayatri Spivak. Her work has challenged the western critic’s tendency to appear as though they are speaking from a neutral and objective perspective, and demonstrated how these claims conceal the ways that such critics represent and re-present a subject in oppressive ways (Spivak 1995). Although her scholarship is rooted in deconstructionism and postcolonial theory, her concerns about objectivity’s relationship to white western oppression intersects with US-based critical race theory, where topics like objectivity are central. Indeed, as Michael Omi and Howard Winant have explained, racism in the United States proliferated when figures like Dr. Samuel Morton established so-called “objective” biological measures like cranial capacity to devalue the Black community while elevating the white one (Omi and Winant 1994).

I mention these critics not to argue that one must necessarily introduce a piece of advanced critical race theory or postcolonial theory to our students when using Wikipedia in the composition classroom (although this would of course be a welcome addition for whoever wishes to do so). After all, I never set Spivak’s “Can The Subaltern Speak?” as reading for my students. But what she revealed to me about the impossibility of neutrality in that famous paper prompted me to ask my students about Wikipedia’s NPOV policy in our class discussions and during our comparative exercise, rather than taking that policy for granted and inviting my students to adopt it. If instructors judiciously inflect their pedagogical practices with the viewpoints that critical race theory and postcolonial theory provide, then we can put ourselves and our students in a better position to see how digital writing on sites like Wikipedia are not exempt from the dynamics of power and oppression that exist offline. Other areas in critical race theory and postcolonial theory can also be brought to bear on Wikipedia, and I invite others to uncover those additional links. Disciplinary boundaries have inadvertently created the impression that discoveries in postcolonialism or critical race theory should concern only the scholars working within those fields, but the acute sensitivity towards power, marginalization, and oppression that these fields exhibit mean that the viewpoints their scholars develop are relevant to any instructor who desires to foster a more socially conscious classroom.

2. The Edit-a-Thon: Failure as Subversion

Composition classes that use Wikipedia usually conclude with an assignment where students are invited to write their own entry. For cultural studies courses in particular, students address the lack of content about minority cultures or groups by participating in a themed Edit-A-Thon organized by their instructor. These Edit-A-Thons mirror the Edit-A-Thons hosted by social justice organizations and activism groups outside of the university. These groups usually plan Edit-A-Thons in ways that guarantee maximum success for the participants because many are generously volunteering their time. Moreover, for many participants, these Edit-A-Thons are the first time where they will write for Wikipedia, and if the goal is to inspire them to continue writing after the event, then it is crucial that their initial encounter with this process is user-friendly, positive, and productive. This is why these events frequently offer detailed tutorials on adopting Wikipedia’s content policies, and provide pre-screened secondary source materials that adhere to Wikipedia’s guidelines about “no original research” (writing about topics for which no reliable, published sources exist) and “verifiability” (citing sources that are reliable). Indeed, these thoughtful components at the Art + Feminism Edit-A-Thon event I attended a few years ago at the Guggenheim Museum ensured that I had a smooth and intellectually stimulating experience when I approached Wikipedia as a volunteer writer for the first time. It was precisely because this early experience was so rewarding that Wikipedia leapt to the forefront of my mind when I became an instructor, and was searching for ways to expand student interest in writing.

It is because I am now approaching Wikipedia as an instructor rather than a first-time volunteer writer, however, that I believe we can amplify critical engagement with the encyclopedia if we set aside “success” as an end goal. Of course, there is no reason why one cannot have critical engagement and success as dual goals, but when I was organizing the Edit-a-Thon in my class, I noticed that building in small instances of “failure” enriched the encounters that my students had with Wikipedia’s content policies.

The encyclopedia stipulates that one should not write about organizations or institutions that they are enrolled in or employed by, so I could not invite my students to edit the entry about UVa’s history itself. Instead, I invited them to create a new entry about the history of student activism at UVa using materials at our library.[4] When I was compiling secondary sources for my students, however, I was more liberal with this list in the Spring than I was in the Fall. Wikipedians have long preferred secondary sources like articles in peer-reviewed journals, books published by university presses or other respected publishing houses, and mainstream newspapers (“Wikipedia: No Original Research” 2020) to ensure that writers typically center academic knowledge when building entries about their topic. Thus, like the many social justice and non-profit organizations who host Edit-A-Thons, for Fall 2019 I pre-screened and curated sources that adhered to Wikipedia’s policies so that my students could easily draw from them for the Edit-A-Thon.

In Spring 2020, however, I invited my students to work with a range of primary and secondary sources—meaning that some historical documents like posters, zines, and other paraphernalia, either required different reading methods than academically written secondary sources, or were impossible to cite because to write about them would constitute as “original research.” Experiencing the failure to assimilate other documents and forms of knowledge that are not articulated as published texts can help students interrogate Wikipedia’s lines of inclusion and exclusion, rather than simply taking them for granted. For example, during one particularly memorable conversation with a student who was studying hand-made posters belonging to student activist groups that protested during UVa’s May Days strikes in 1950, she said that she knew she couldn’t cite the posters or their contents, but asked: “Isn’t this history, too? Doesn’t this count?”

By the end of the Spring Edit-a-Thon, my students produced roughly the same amount of content as the Fall class, but their reflection papers suggested that they had engaged with Wikipedia from a more nuanced perspective. As one student explained, a Wikipedia entry may contain features that signal professional expertise, like clear and formal prose or a thick list of references drawn from books published by university presses and peer-reviewed journals, but still exclude or misconstrue a significant chunk of history without seeming to do so.

A small proportion of my students, however, could not entirely overcome one particular limitation. Some continued describing Wikipedia’s writing style as neutral even after asserting that neutrality in writing was impossible in previous pages of their essay. It is possible that this dissonance occurred accidentally, or because such students have not yet developed a vocabulary to describe what that style was even when they knew that it was not neutral. My sense, however, is that this dissonance may also reflect the broader (and, perhaps, predominantly white) desire for the fantasy of impartiality that Wikipedia’s policies promise. Even if it is more accurate to accept that neutrality does not exist on the encyclopedia, this knowledge may create discomfort because it highlights how one has always already taken up a position on a given topic even when one believes they have been writing “neutrally” about it, especially when that topic is related to race. Grasping this particular point is perhaps the largest challenge facing both the student—and the instructor—in the pedagogical approach I have outlined.