Introduction

The Archives & Special Collections (A&SC) Department at the University of Pittsburgh endeavors to play a central role in instruction involving the use of primary source materials. In this article, Jeanann Haas, the Coordinator of Special Collections and Preservation, and Jennifer Needham, an archivist, discuss the variety of ways they have worked together to engage students in primary source research, including working with faculty to develop assignments that result in blogs, zines, data sets, and visualizations, what we call “creative outputs.” Since 2013, A&SC developed and continues to build upon a dynamic instruction program through active outreach and recruitment to invite faculty to bring their classes to visit the reading room and engage with primary sources. A&SC collaborate with faculty to design assignments and in-class exercises that incorporate primary sources and offer students the opportunity to generate and share their original research and discoveries in creative ways. This article presents a series of case studies in which students worked with primary sources and used digital humanities methods to present their research in creative ways.

Recent literature on archives and special collections reveals that the information literacy movement impelled the profession to champion participatory and collaborative learning with primary sources, thus departing from the show-and-tell model of instruction where students simply look at rare books and archives as librarians and archivists talk about them (Carini 2016, 192; Garland 2014, 326). Participatory and collaborative learning allows archivists and librarians to collaborate with faculty to support student researchers in analyzing primary sources to create, produce, innovate, and contribute to scholarship in creative and visual ways (Vong 2016, 150; DeSpain 2011, 30). Creating opportunities for students to engage with primary sources using digital humanities methods not only advances research-based learning but also fosters collaboration and communication among faculty, librarians, archivists, and digital humanists (Davis, McCullough, Panciera, and Parmer 2017, 482). In this article we share our experiences collaborating with faculty to support their pedagogical goals, design assignments that transcend the traditional research paper, and challenge students to produce creative outputs that further visualize and showcase their research.

Zines as Creative Outputs

In 2017, an English Department professor contacted A&SC to discuss possibilities for incorporating primary source research and creative projects in the two courses that she was teaching in the upcoming semester: “Women in Literature” and “Science Fiction.” The professor assigned students to create a zine or write a final paper about alternative publishing methods that would draw on class readings and discussion, personal interests, and materials consulted during their visit to A&SC.

During their visit to the A&SC reading room, students consulted science fiction fanzines, science fiction pulp magazines, feminist zines, and underground and alternative press newspapers in order to gain an understanding of pre-internet modes of communication and creative labor. As students explored the materials they completed a worksheet, designed by the professor, to prompt close examination of the materials. They were asked to consider the publisher, format, content, imagery, advertisements, and other interesting features.

Students enrolled in “Women & Literature” consulted feminist newspapers and newsletters from the 1970s including titles such as WomanSpirit, Broomstick, and Allegheny Feminist. They also reviewed lesbian feminist materials from the 1990s, comic books with women protagonists, and science fiction fanzines created by women. During their class visit, students studied the materials and considered the different literary approaches that female authors employed as well as women authors’ many perspectives on political upheaval, personal quandaries, and oppression in different literary and societal traditions. The “Science Fiction” course worked with a variety of science fiction and comic fanzines such as Cosmic Reflections, Granfalloon, Feinzine, and Cerebro. Students also worked with science fiction pulp magazines such as If and Galaxy, and superhero and science fiction comics like Superman, X-Men, Flash Gordon, and Buck Rogers.

Students in both courses returned to the reading room outside of their class time to perform a closer reading in preparation for their final assignment. The aim of the zine assignment was to encourage students to create a self-published and original work in response to the materials that they researched and consulted. Creating zines is a “reflection-based activity” that models a “student-centered approach to learning” (Vong 2016, 63). Students were challenged to think critically about the ideas, values, and events not necessarily covered by the mainstream media. In addition, those in “Science Fiction” considered the history of fandom and the subculture and emergence of the genre as a whole.

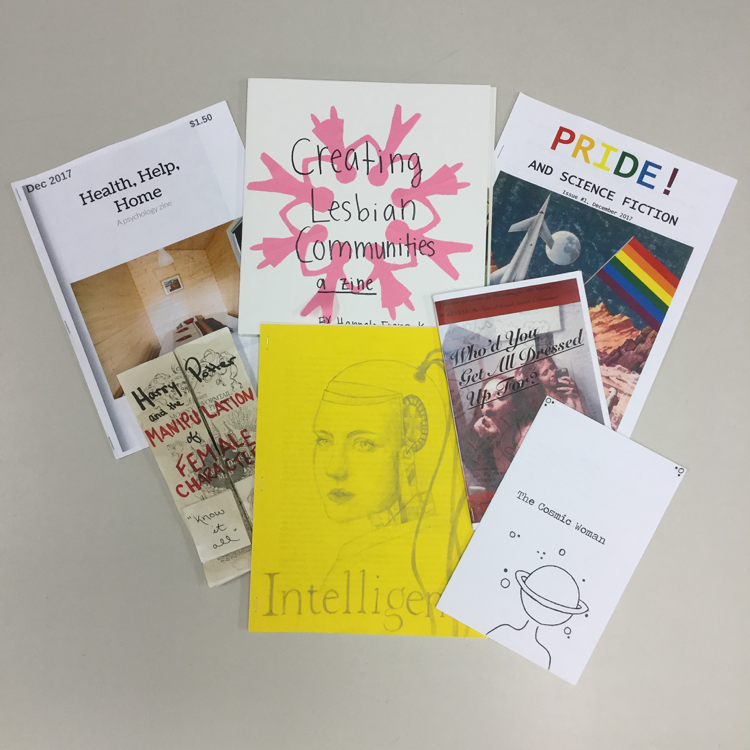

The students’ creative output was engaging and enlightening. The zines produced by students in both courses included reflections on class readings; editorials; original fiction, poetry, and art; and repurposed articles and headlines. Many of the zines modeled the common zine aesthetic and incorporated magazine clippings, repurposed illustrations, collage, and other DIY features. Students focused on gender representation in science fiction, women in the scientific community, lesbian culture and community, sexual harassment and assault, and mental illness. For the “Women & Literature” course, one zine addressed sexual harassment and the #MeToo movement, discussing the historical nature of contemporary debates. The author hopes that their zine will reach a wider audience and provide support for those who have experienced sexual assault.

A student in the “Science Fiction” course created their zine to address the lack of LGBTQ+ representation in mainstream science fiction and included a short story and reading list of what they believe to be quality queer content in books, television, and video games. They modeled the cover art after a specific issue of Cosmos Science Fiction and Fantasy Magazine that they consulted in A&SC and tried to emulate text produced on a typewriter. Elated by the final assignment, the faculty member showcased the zines at Pitt’s Digital and Handmade Showcase. She plans to explore this type of assignment in future courses. Taking inspiration from the professor and her assignment, A&SC hopes that this non-traditional method of scholarly output is something that can be further utilized by other professors. With the students’ permission, the class gifted the zines to the A&SC to enhance the zine collection, preserve their creative output, and serve as an example of student-produced work.

The zine collections also inspired another student who received a Brackenridge fellowship which provides undergraduates with a summer stipend so that they can devote themselves full-time to a creative or analytic research project. While other scholarship awardees were directed to submit a research paper as a final deliverable, this student negotiated to create a series of zines. She consulted with the science fiction, comic, and feminist zines as well as the contemporary zine holdings at Pitt’s Frick Fine Arts Library and Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Public Library. Interested in placing the zine, as a format, in historic context, she conducted research throughout the summer in order to publish a variety of zines based on her findings that outline zine history, how to make a zine, the social significance of the medium, and a personal zine reflecting upon her research experience. In addition, she hopes to start a zine club at the University in order to provide direction, resources, and space to students interested in self-publishing their own zines.

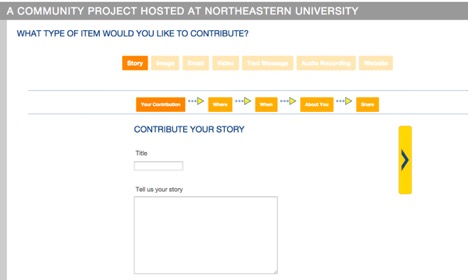

Digital Humanities Application

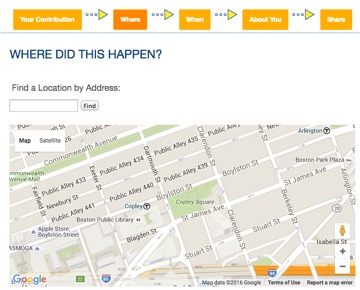

Many faculty have expressed interest in using digital humanities methods to provide opportunities for students to share research as an alternative to the traditional research paper. Special collections, archives and rare books can provide students with the resources to inform compelling digital humanities projects. At the University of Pittsburgh, the Digital Scholarship Services (DSS), part of the library system, provides support for digital humanities teaching and research. They work closely with A&SC to recommend digital humanities applications to students and professors. For example, the Composing Digital Media course requires that students, “compose digital media while exploring the rhetorical, poetic, and political implications of multiple writing platforms. Students will learn how to compose a range of critical media objects using web-authoring languages, text, sound, images, and video in proprietary and open-source software” (University of Pittsburgh, 2018). The professor required students to visit A&SC to perform a close reading of science fiction fanzines, comic books, 1970s rock magazines, and feminist and gay press materials from the 1970s and 80s. The assignment asked students to categorize content based on a predetermined set of tags relating to gender and race, organized in the form of a digital timeline. She wanted the visual representation of the text to help students contextualize the categorized content over time. In addition, the faculty member wanted the final product to benefit A&SC. Many of these materials have not been digitized or indexed, so the professor hoped the project would render the materials more discoverable. DSS recommended that she use Timeline JS because it is a free, easy to learn software application that can quickly produce a digital timeline.

During the students’ initial visit to A&SC, the professor and archivist led a Timeline JS tutorial and introduced the content that would be incorporated into the timeline. After the students consulted the materials, the class regrouped and decided to assign tags including trans communities, objectification, sexual norms, diversity, empowerment, and animosity. Anticipating challenges, the professor required students to compose one timeline as practice before delving into the full assignment. Students voiced concern that the categories were too broad and difficult to tag and worked together to choose new tags that they believed would more accurately describe the content and settled on overcoming objectification, call to action, defying gender roles, verbal violence, and racial diversity. Although the new categories were still broad, they were nuanced enough to aid in the completion of the assignment.

The professor divided the class into groups of 3-4 students and directed them to work with a specific format such as fanzines, rock magazines, or feminist newspapers. Each student read three articles from their assigned format and assigned tags, took photographs, and entered metadata about these publications into a Google Spreadsheet. The spreadsheet detailed the bibliographic information along with the tag. Students also drafted a synopsis of each article that would position their chosen reading in the context of the tag. Timeline JS generated the timeline using the information on the spreadsheet. Examples of the timelines include Science Fiction Fanzines: A Collection of Thoughts, Theories, and other Things and Pop Rocks.

Battershill and Ross recognize that “many activities in the digital humanities require adaptability, creativity, and openness” (Battershill and Ross 2017, 5) and urge practitioners to keep an open mind and learn from those things that don’t always turn out as expected. Due to the complexity of the project, a data visualization tool may have been better suited, but visualization tools tend to require time and effort to learn beyond the two-week scope of the project. Nevertheless, this exercise still proved to be valuable in exposing students to a new digital humanities tool that challenged them to use close reading to produce a digital timeline. Furthermore, the assignment empowered students to participate in the decision-making process, negotiate and build consensus, and modify the categories based on their research and initial experiences with primary sources.

Social Media

While timelines are a great way of visualizing key events within the context of a specific period of time, multimodal social media blogs also serve as effective tools for telling a compelling narrative. Composing a blog post is an important exercise in clear and concise writing, and it also allows students to share their work with a larger audience. In addition, when students compose multimodal blogs related to collections, they help to publicize these collections to potential future researchers.

Several years ago, A&SC started using the blog platform Tumblr to highlight collections in an engaging and visual way. Student employees served as the content creators and researched and wrote blogs based on their interests, drawing inspiration from A&SC collections. Recognizing that Tumblr could also be a great way to engage classes, A&SC invited faculty to consider assigning blog entries as alternatives to regular writing assignments.

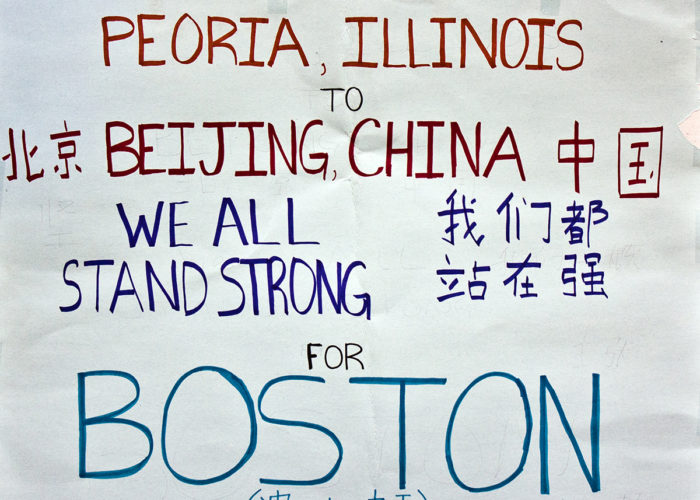

In one example, we helped a professor design a multimodal blogging assignment in which students would collaborate with local community groups to help them memorialize their histories. This was part of a course offered in the History of Art and Architecture Department (HAA) titled, “Nationality Rooms: Visualizing Heritage in Pittsburgh.” The Nationality Rooms are thirty classrooms, located in the University of Pittsburgh’s historic Cathedral of Learning, that depict the national and ethnic groups that immigrated to Pittsburgh and also serve as University classrooms. Committees consisting of community representatives from across the world were formed to design, fundraise, and support the construction of the classrooms to represent different cultural heritages. The host committees’ planning, design, and construction for each of the Nationality Rooms are documented in the archives and include meeting minutes, correspondence, architectural drawings, and photographs. The course required each student to choose a specific room and research that room’s archive in order to identify how the host committee wanted to memorialize and represent themselves. Along with a paper and oral presentation, students wrote a short blog post using their paper abstract. For the last two weeks of the semester we featured one post per day on the A&SC Tumblr site. Some of the topics included, “Keeping Greek Heritage Alive during World War II,” “Showcasing Japan’s Cultural Past to Facilitate American Interest,” and “The Politics of the Syrian-Lebanese Nationality Room: Memorializing Unity and the Arabic-American Identity.”

The posts were written well, however, they focused more on the room as a whole and not on one aspect of the room in conjunction with a primary source from that room’s archive. Also, they did not include images of materials from the archives, but rather images of the rooms. From this experience, we learned that the students required more explicit directions. Although the instructions for the assignment were communicated to students verbally during the initial class visit, it would have been better to provide the students with written instructions outlining the requirements for the post.

Some faculty maintain their own class blogs and assign students to create posts using A&SC materials. A&SC hosted an Introduction to Creative Writing class to look at scrapbooks from S. Leo Ruslander. Solomon Leo Ruslander (1879-1976) was a tax lawyer in Pittsburgh who compiled thirteen scrapbooks which document his professional and family life. The scrapbooks contain letters, photographs, event programs and invitations, postcards, newspaper clippings, and ephemera that document his wedding, family vacations, and material relating to local and regional associations[1]. Interacting with personal artifacts such as diaries draws researchers closer to the object’s history and cultural significance by evoking personal reflections and emotion (Lanning and Bengston 2016, 9). The professor asked students to spend time consulting with the scrapbooks and to each create their own, individual, creative portrait of Mr. Ruslander based on the information gleaned through the scrapbooks. Using WordPress, the class compiled their essays and created an online class magazine titled Seventeen Ways of Looking at S. Leo Ruslander. This project motivated students to embrace different roles throughout the creation process such as author, editor, reviewer, and publisher, while simultaneously establishing a meaningful connection with primary sources (DeSpain 2011, 26).

Faculty assign blogs to teach students how to articulate their research in shorter writing exercises that ask students to write succinctly and for a popular audience. In addition, assigning hashtags to their posts enable students to consider ways to enhance discoverability. Students often include links to their blog posts in job applications to demonstrate their writing skills. In addition, the blogs raise awareness of collections as posts are “liked” or “reblogged” by other individuals, libraries, or museums. They are indexed and discoverable through search engines such as Google, rendering these stories available to future researchers. To encourage faculty to incorporate blogging into their writing assignments, A&SC has created guidelines to assist faculty in scoping projects and has provided information about formatting, content length, and images.

Independent Student Research and Digital and Creative Outputs

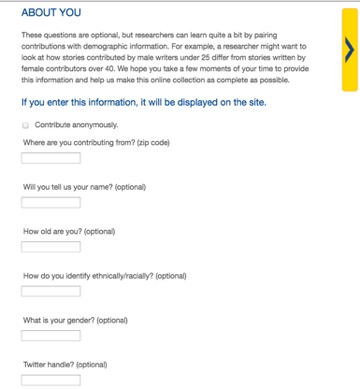

In addition to class blogging assignments, independent student research opportunities teach students how to perform research using primary sources. As part of a larger library initiative and in partnership with Pitt’s Office of Undergraduate Research (OUR), A&SC offers the Archival Scholar Research Awards (ASRA) to encourage undergraduate scholars and researchers from the humanities to engage in original research using archives, special collections, and primary sources at the University of Pittsburgh. The ASRA program creates opportunities for students to connect with faculty mentors as well as with librarians, archivists, and curators who support student research and introduce students to collections. ASRA students also engage in collections work that supports their individual research projects and enhances the discoverability of library and archival resources. A&SC strives to find ways to incorporate creative outputs such as producing zines, timelines, social media, and other digital applications into the ASRA students’ collections work while simultaneously giving the faculty mentor a glimpse of what might be possible to include in their class assignments.

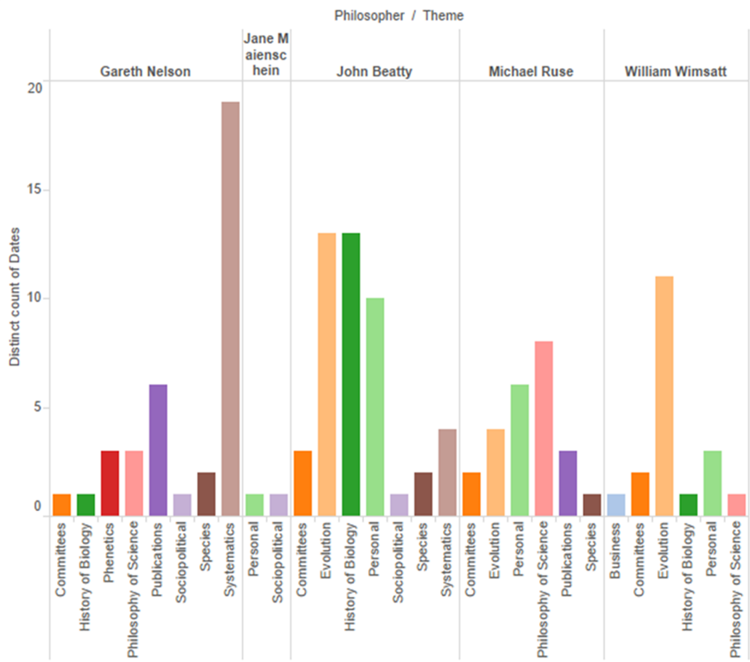

The ASRA program has made it possible for A&SC to witness the enthusiasm and passion that a researcher has when they detect a sign or clue that provides greater insight into their research. An undergraduate Biology and Philosophy major and ASRA recipient studied the archives of David Hull because it was a newer collection that had never been researched. Hull was one of the philosophers who founded the modern subdiscipline of Philosophy and Biology. The student began her research by focusing on the correspondence files in the Hull Papers to situate Hull’s thinking among twentieth-century philosophers of science within the century’s wider cultural movements. She carefully documented major themes, correspondents, events, locations, and dates that she encountered in the archive in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. The student also created Tumblr posts to raise awareness about the Hull papers and document the progress that she was making in her research.

Through her research, this student witnessed firsthand the debates among philosophers, and scientific philosophy theories that differed from the “winning” side. Based on this research, the student concluded that subject material taught in general philosophy classes is often from the viewpoint of the “winning” or most popular side of a theory. The correspondence files also revealed how the philosophers networked with one another, discussed ideas, and formulated their theories. From this data, she identified patterns in the letters and developed the thesis that Hull’s ideas synthesized the opinions of many different philosophers and that the best ideas are the products of cooperation. She worked closely with the DSS to find a tool that could visually support her theories and that she could embed in her poster for an end-of-term presentation. Figure 2 illustrates how she was able to carefully examine the manuscripts, recognize and interpret patterns in the author’s writings, create a narrative, and draw powerful conclusions about Hull’s work (Carini 2015, 194). In addition, she used the data in her Microsoft Excel spreadsheet to create a visualization using the data visualization and analytics application Tableau.

This student’s experiences and discoveries demonstrate the importance of original research with primary sources. This student is one of the first researchers to use the David Hull papers and she made some significant discoveries that other researchers can build upon; she and her Faculty Mentor published a paper titled “David Hull Through His Own Philosophical Lens” focusing on this research and made it available in D-Scholarship, the University of Pittsburgh’s institutional repository.

Another success story from the ASRA program revolves around three students who received the ASRA award to conduct research using the Black Panther, the newspaper published by the Black Panther Party. The students each conducted their own individual research using the Black Panther. They studied the Black Panther Party’s foreign involvement and support, the origins of the publication’s visual vocabulary, their use of propaganda, and the artwork of Emory Douglas, Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party. At the same time, students consulted every issue of the physical newspaper that was held in Pitt’s archive and recorded information about the publication in a Google spreadsheet. Their goal was to create a dataset that would aid their research and provide insight into collections that are not necessarily discoverable through the library’s catalog and allow researchers to collect, process, and critically analyze data using quantitative methods. They recorded information about the inventory and missing issues, the cover art and accompanying headline, the back cover art, and any other art found within each issue. In addition, students noted articles about women’s health, women in prison, women’s leadership within the party, and the party’s international connections. The faculty mentor, who supervised the students’ research, consulted this data set in order to design a new course on conflict and art. Further, this data set will also benefit A&SC in assisting other faculty interested in incorporating the newspaper into their curriculum.

The intent is to make this Black Panther newspaper dataset public so future researchers can better locate information. As Chester et al. recognize, “masses of data and statistics are no substitute for close reading, but they create an opportunity for individual scholars to pose new questions to sets of data never before assembled” (Chester 2018, 67). However, in retrospect, A&SC needed to coach the three students to adhere to the same format when entering their data. As a result, the dataset is inconsistent and requires more revision before it can be released to the public. The project did successfully identify content for class visits and has the potential to feed into other digital humanities projects. When students engage in primary source research, they move away from being consumers of information to producing, creating, and contributing their theories and ideas to the greater body of scholarship. A&SC also supports students engaging in independent research or internships under the direction of faculty. These autonomous pursuits offer a little more freedom to experiment with creative outputs and are not necessarily confined to a specific class or curriculum. To this end, Pitt librarians seek out academic departments who wish to offer undergraduate students internship opportunities and place them in A&SC for course credit. These internships support original research and provide a mechanism for students to share their research in creative ways. For example, an undergraduate student focusing on Museum Studies focused her internship on Japanese printmaking and consulted Japanese prints in Pitt’s University Art Gallery, Carnegie Museum of Art, and in A&SC’s Walter and Martha Leuba’s print and broadside collection. The student compiled detailed information about selected prints; enumerated, re-housed, and labeled prints; and investigated unattributed prints for the eventual digitization of this material. She aimed to create a virtual exhibition of Japanese prints using Omeka, a free and open source web-publishing platform for content management and online exhibit creation, and to promote the Leuba collection prints and her research through Tumblr. Given her personal research focus on twentieth-century Japanese woodblock prints, she specifically took interest in a piece by Kiyoshi Saitō (1907-1997) titled Clay Image. The student realized that the people featured in the print were actually the hollow figures made from terracotta clay, called Haniwa, which she learned about that previous year in an Asian art class. She then shared this new insight on her blog and featured this print on her Omeka site. Through this internship, the student became familiar with the Japanese prints within Pitt’s collections and became proficient in using Omeka to help communicate her research discoveries. In addition, the student’s contributions will help lead to increased discoverability of the prints.

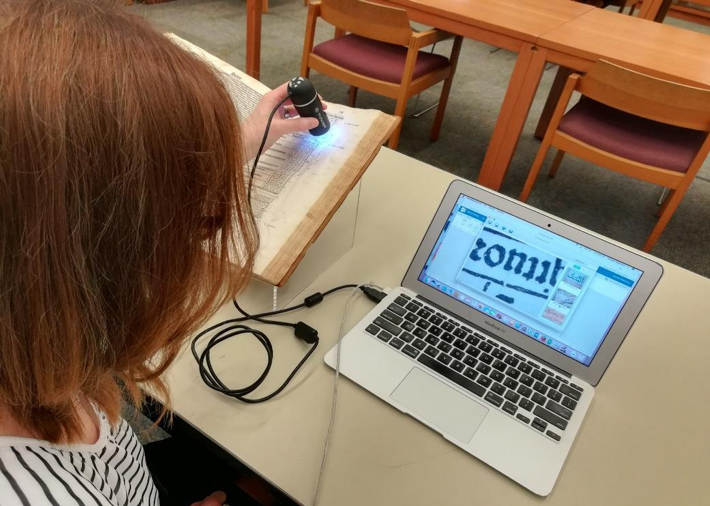

Digital Microscopes

In addition to encouraging creative outputs, A&SC encourages students to interact with collections through in-class exercises. When a professor teaching Making the Book brought his personal digital microscope to a class visit, A&SC immediately realized the potential to engage students in a method of active learning often reserved for the biological sciences. When the department purchased five microscopes[2] for class use, faculty enthusiastically requested that they be made available for their students. The ability to see cotton fiber threads in 17th-century paper or to distinguish a woodblock print from a lithograph allows students to identify and study the materiality of paper, ink, and printing methods. Peter Carini notes that “Primary source materials come with special and unique challenges, particularly in an era when young people are increasingly electronically literate but have less and less interaction with physical documents” (Carini 2016, 193). Classes focusing on the history of the book appreciate being able to see and actually touch older books, compare paper to parchment, witness real evidence of animal skins in books, and study features like marginalia, decorations, watermarks, and clues to ownership and provenance such as library stamps, call numbers, annotations, etc. Faculty feedback indicated that the digital microscopes and physical interaction served as a wonderful complement to the theoretical discussions in the classroom by allowing this first-hand, philological experience. The microscopes helped students better observe examples of stereotyping, electrotyping, linotype, and rotogravure to understand how the press was mechanized. Similarly, they compared different machine-made papers such as wood pulp, typescripts, dime novels, and mass market magazines to hand-made paper found books produced during the hand-press period and fine press books created during the Arts and Crafts movement.