Introduction

Information pollution, information overload, and infoglut are some of the most common terms used to describe the “almost infinite abundance” and “surging volume” of information that “floods” and “swamps” us daily (Hemp 2009). Popular media articles appear regularly offering tips and strategies to “cope with,” “conquer,” and even “recover” from information overload (e.g., Harness 2015; Shin 2014; Tattersall 2015). Information Fatigue Syndrome, a term coined in 1996, refers to the stress and exhaustion caused by a constant bombardment of data (Vulliamy 1996). In Data Smog: Surviving the Information Glut, David Shenk (1997) argues that the surplus of information doesn’t enhance our lives, but instead undermines and overwhelms us to the point of anxiety and indecision. According to research conducted by Project Information Literacy researchers, “it turns out that students are poorly trained in college to effectively navigate the internet’s indiscriminate glut of information” (Head and Wihbey 2014, para. 7).

The study presented here emerged from “New Information Technologies,” an undergraduate course in the media and communication department at a small, private, liberal arts college in the northeast United States. The course introduced students to key concepts and tools for thinking critically about new information technology and what it means to live in a digital, global society. Course goals underscored the importance of developing students’ capacities as digitally literate learners and citizens of a global network society. We intentionally articulated course learning goals around both the content area and the practices of digital literacy embedded in course assignments. We asked students to reflectively discover, organize, analyze, create, and share information using digital tools. Our aim was to empower students with the tools and abilities to thrive in the information ecosystem as both consumers and producers, rather than flounder in information overload. We wanted students to experience research as active agents driving the process through their choices and attitudes. With these broad framing objectives in mind, we developed a multiphase research assignment called the Internet Censorship Project.

In this article, we detail our collaborative development of the Internet Censorship Project assignment and discuss a qualitative analysis of the resulting student work. In our analysis, we focus in particular on students’ engagement in and reflection on the research process and their agency and identity therein. Our close look at the assignment and student learning offers an opportunity to consider the possibilities of integrating digital tools and pedagogies to deepen students’ digital literacy in the context of liberal arts education.

Collaborating for Digital Literacy

This course provided ideal opportunities for collaboration between an information literacy librarian and a media and communication professor with shared interests in digital literacy. Our respective disciplines have a common concern for digital literacy, although we often describe and approach the concept in distinct ways. The library and information science field typically uses the term “information literacy,” while media and communication studies uses “media literacy.” The Association of College and Research Libraries (2016) defines information literacy as “the set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning” (3). Media literacy, as defined by the National Association for Media Literacy Education (2017), is “the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, create and act using all forms of communication. In its simplest terms, media literacy builds upon the foundation of traditional literacy and offers new forms of reading and writing. Media literacy empowers people to be critical thinkers and makers, effective communicators and active citizens.” We find common ground in these definitions and the values they convey, especially in the degree to which both disciplines prioritize critical thinking about and active engagement with information. In this paper, we invoke a shared definition of digital literacy, referring to the practices, abilities, and identities around the uses and production of information in digital forms.[1]

Our respective understandings of digital literacy have evolved through extensive and ongoing collaboration with each other and with students. Our disciplines both recognize that definitions of literacies are shifting in the digital environment. One premise of our work is that digital technologies afford new possibilities for collaboration across disciplines and fields. We believe that digital teaching and learning benefit from, if not require, connecting diverse ways of knowing. Digital learning emphasizes connectivity and so we have designed our teaching approach to model the same.

What matters most here is how these definitions come to bear on framing student learning outcomes in this course and assignment. There were no digital literacy learning outcomes explicitly embedded within the course syllabus prior to this collaboration. Discussions about how and where to integrate digital literacy goals within existing course assignments gave rise to our collaboration. These discussions revealed that while the course aimed to promote critical thinking and analysis of the so-called information age, it did little to intentionally link theory to critical practice in ways that highlighted development of students’ digital literacy habits and abilities. The library’s statement on information literacy, inspired at the time of its creation by an earlier iteration of the Association of College and Research Libraries information literacy definition, offered a welcome starting point and with very little modification was introduced as a course goal (Trexler Library, Muhlenberg College 2010). Among course objectives, the syllabus newly included this statement: “students in this course will have opportunities to develop capacities as information literate learners who can discover, organize, analyze, create and share information.”

Assignment Design and Instructional Approaches

The Internet Censorship Project required students working in pairs or small groups to investigate the state of internet censorship and surveillance in different countries. The project extended across four weeks in the latter half of the semester. Students shared their research findings in culminating in-class presentations. The entire process was designed to encourage students to link their critical theoretical understanding with digital literacy practices. We purposefully integrated digital tools and pedagogies throughout the assignment to help students move beyond only amassing and describing sources to higher order research activities and more advanced digital literacy behaviors and attitudes.

Our first implementation of this assignment in fall 2013 revealed some of the general challenges of asking students to critically engage with information. Students tended to gather large amounts of information and dump it into their work without clear purpose or analysis. Ultimately, this resulted in lackluster project presentations in which students’ facility with the mode of digital presentation (Prezi) was often more impressive than the story being shared. These issues are not unique to this assignment, course, or campus. Many educators have likely seen evidence of students’ struggles with “information dump.” Information dump demonstrates students have collected relevant data, but they are unable to present it logically or think about it critically and analytically. This challenge relates to larger issues with helping students develop and strengthen their research habits and abilities. There is often a wide gap between where students begin and where we want them to arrive with respect to information gathering, evaluation, analysis, and synthesis. They often do not successfully make the leap from one ledge to the other (Head 2013; Head and Eisenberg 2010). Frequently what seems to be missing is students’ engagement with research as a process and their critical reflection on that process.

Among the many personal benefits students gain from research, they “learn tolerance for obstacles faced in the research process, how knowledge is constructed, independence, increased self-confidence, and a readiness for more demanding research” (Lopatto 2010). Participating in the research process also promotes students’ cognitive development, supporting their transition from novice to expert learners. Undergraduate research encourages students to exercise critical judgment and to make meaning of what they are learning. Such experiences help students construct a sense of themselves as researchers, gaining a sense of agency and ownership of the research process. If today’s students are “at sea in a deluge of data” (Head and Wihbey 2014), carefully crafted research assignments can help them acquire the skills and awareness that serve as life rafts and anchors.

This kind of work presents opportunities to promote students’ metacognition, or awareness of and reflection on their thinking and learning (Livingston 1997). A metacognitive mindset can help students identify their research as a process in which they are located and over which they have agency. “Successfully developing a research plan, following it, and adapting to the challenges research presents require reflection on the part of the student about his or her own learning” (Carleton College 2010, para. 5). By reflecting on their steps and thinking, students can perhaps more easily recognize their choices and beliefs, enhance their ability to plan for and guide their learning, as well as adapt in the face of future challenges or new situations (Lovett 2008). “Seeing oneself as capable of making the crossing to a better understanding can be empowering and even exhilarating….The ability to manage transitional states might be, then, a transferrable learning experience, one that involves increasing self-knowledge and confidence” (Fister 2015, 6).

Close review of Internet Censorship Project student learning outcomes in 2013 informed our revisions to the assignment in fall 2014. (See Appendix A for the assignment.) We strengthened the assignment by gearing it more toward process and reflection. Our goal was to better support students as they worked to bridge the gap, from start to finish, in their research knowledge and abilities. This time around, we emphasized steps within the research process and prioritized the development of critical and reflective thinking about information. We did this by redesigning the project phases and intentionally using carefully selected digital tools.

In the first phase, student partners collaborated to select and organize research sources about internet censorship and surveillance in their selected countries. They used a collaborative, cloud-based word processing application (Google Docs) to gather and share information with each other as they discovered it, working both synchronously and asynchronously. Documents started as running lists of sources with links to original content, but were to evolve into meaningfully and logically organized and annotated texts that demonstrated critical thinking about sources. In fall 2014, we dedicated more in-class time modeling for students how documents might evolve beyond mere lists into collaborative space for organizing, summarizing, assessing, and interrogating information.

We also integrated a crucial new element, a photo journal created in WordPress, into the assignment as a metacognitive bridge to support students’ development from information gathering to presentation. We selected WordPress for this activity for a number of reasons. On a practical level, we have a campus installation of WordPress and strong technology support for it. WordPress is easily customizable, extendable, and enables students to work with the various media types we sought to promote with the assignment. Just as importantly, using WordPress aligned with one of the underlying goals of the course to deepen students’ critical reflection of their own digital presence. We wanted them to gain experience working in a widely-adopted open source environment—approximately 25% of all websites that use a content management system run on WordPress (Lanaria 2015)—so that they might compare this platform to their experiences within commercial social media platforms. Overall, WordPress enabled us to provide students with hands-on experience as information producers that developed digital literacy practices that could serve them well beyond this assignment and course.

The photo journal transformed the assignment in important ways and is the focus of our case study. We described its purpose to students in the following way:

The journal is your individual representation of the process as you experience and construct it. The Photo Journal is created in WordPress and includes photos, images, drawings, screenshots, and narrative text and captions that take the viewer behind the scenes of your research process. Think of this as “the making of” your project, uncovering the questions and thinking behind your project, and documents the “what, why, where, and how” of the research you are producing.

Students were required to create a minimum of 10 posts, the first of which asked students to reflect on their ideal research environment. The final post invited students to contemplate their presentation and completion of the project. In between, the remaining eight journal entries were designed to document and reflect on students’ research experiences. We provided optional prompts to kickstart their posts, including the following:

- What do you know about the topic? What do you want to know?

- Why does this source matter?

- How did you get started?

- What led you to this source?

- What questions does the source raise for you?

- How does the source contribute to other knowledge?

- What do you know now? What have you learned?

We constructed the photo journal element to activate for students an attitude of critical engagement and a more reflective, metacognitive mindset (Fluk 2015). In documenting their research processes, the photo journal was intended to surface students’ thinking for both themselves and us as instructors. We wanted to promote their reflection on steps in the research process and, therefore, change and deepen that process. By modeling and scaffolding these behaviors and attitudes through the phases of the assignment, we hoped to move students progressively toward stronger engagement and understanding. Rather than drowning in information overload, we hoped to develop students’ sense of agency to be able to comprehend, communicate about, make meaning of, and reflect on their information consumption and production. By asking students to include images as representations of their research, we further hoped to make the research more visible as a process.

Through our qualitative analysis of students’ photo journals in this case study, we attempt to better understand both the connections students make, as well as where they need help to bridge the gaps in their learning. Our case study explores how we can use digital technologies and digital pedagogy to better foster students’ development as digitally literate researchers.

Methodology

In this research, we look closely at student learning outcomes aligned with the digital literacy goals of the Internet Censorship Project. Collectively, the 17 students in fall 2014 generated 170 photo journal entries. Our data collection, coding, and analysis were conducted using Dedoose, a cloud-based platform for qualitative and mixed methods research with text, photos, and multimedia. The program enabled us to organize and code a large set of records.

Each journal entry included a narrative update or reflection on students’ research and a related image. While designated a “photo journal,” students’ posts included a considerable amount of text that is central to this study. Our qualitative content analysis concentrated on students’ description of, and reflection on, their research sources and their research steps and behaviors. We also constructed a series of identity codes to indicate those instances where students self-consciously located themselves within their research and reflected on their research as practice.

Analysis of Students’ Journals

Students’ journals varied in depth, detail, and critical engagement. Two types of journals emerged clearly: robust and limited. In robust journals, students exhibited a general thoughtfulness and demonstrated a more expansive engagement with content of sources and process. Limited journals were generally more superficial and formulaic, focused primarily on content of sources rather than process. We assign these categories to help improve our pedagogy in order to advance student learning.

In the following sections, we discuss three major areas that emerged from our qualitative analysis of student journal data:

- Students’ engagement as reflected in project pacing

- Students’ attention to process and content

- Students’ identity and agency as digital learners

Students’ Engagement as Reflected in Project Pacing

The journal project required that students submit a minimum of ten posts over four weeks at a suggested rate of two to three times per week. Past experience has shown us that students often tend to squeeze their work into a limited time frame. Student Q, for example, described his usual work tendencies in his journal:

“Typically when I study, do research, or write papers, I end up waiting until the last minute. This isn’t really a voluntary practice, I just can’t find the motivation to prioritize long term assignments until the deadline begins closing in.”

By requiring students to post consistently, we aimed to push them beyond their typical practices. We structured the experience so that students could aggregate and analyze information incrementally over time in order to develop more effective research habits—both attitudes and practices—and to avert information overload. We anticipated that students who worked steadily would have more opportunities for progressive development and reflection and therefore would engage more deeply and critically with the sources and the issues addressed in the assignment. We anticipated that students who worked inconsistently, by comparison, would be more likely to engage superficially and minimally achieve project learning goals. Our interest in “students’ engagement as reflected in project pacing,” then, refers both to the timing of students’ journal posts and the pace of students’ work on the project overall.

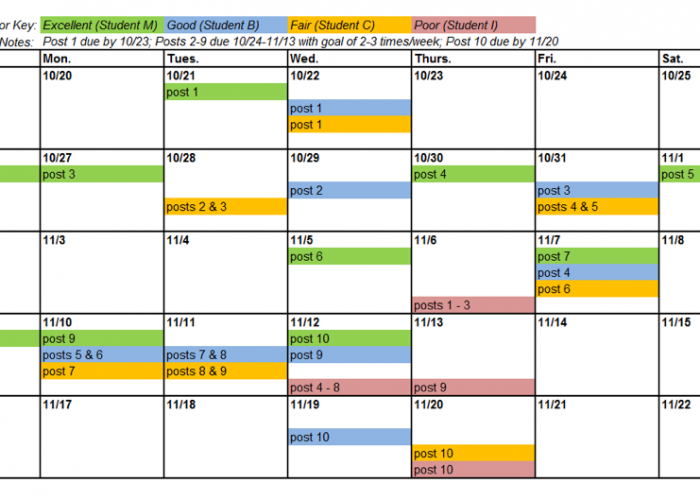

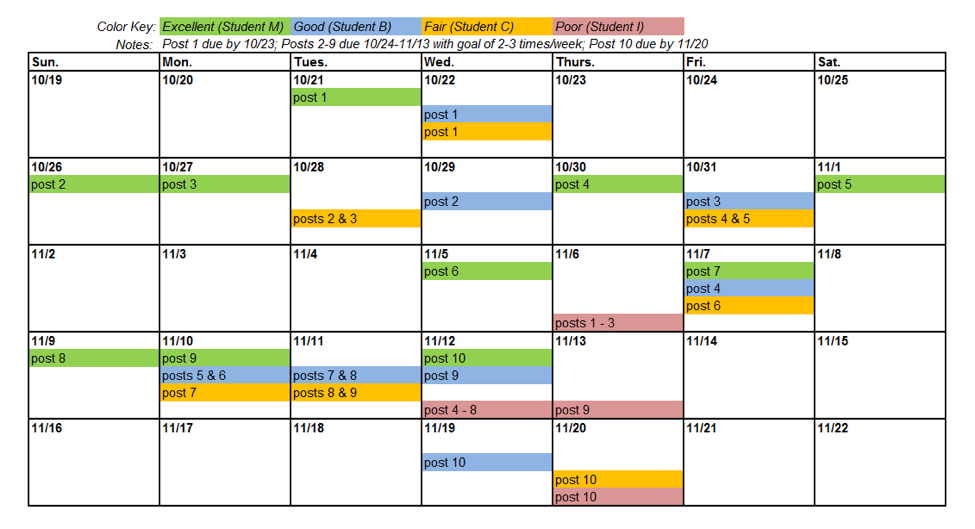

We characterized students’ journal pacing quality as excellent, good, fair, or poor. Excellent pacing described journals with posts spread evenly throughout the project. Good pacing described journals with posts occurring every week of the project, but with some posts closely grouped on consecutive days or even on the same day. Fair pacing denoted journals with some posts closely grouped on consecutive days or the same days and some multi-day or week-long stretches with no posts. Poor pacing referred to journals with posts primarily grouped on just a few consecutive days or the same days and no posts for long stretches of time.

Robust journals were distributed evenly across all four pacing quality categories: two each in poor, fair, good, and excellent. Limited journals, though, were predominantly in the poor pacing category: seven poor, zero fair, one good, and one excellent.

Figure 1. Calendar marked with four students’ journal posting dates, with each student color-coded to represent one of the four pacing quality categories: Excellent, Good, Fair, Poor

Overall, the pattern we saw in the pacing of students’ journals in part supports our intuition. Students who demonstrated lower engagement with content and less reflection on process—that is, students’ whose journals we categorized as limited—appeared to work inconsistently on the project or in a compressed manner. Yet pacing alone is not enough to ensure students’ success, as we saw in the case of robust journals. Their strength was less tied with pacing quality. Perhaps these journals were robust for other reasons such as the students’ developmental levels, their effective integration of our writing prompts, or intrinsic motivation and interest in the assignment. Many factors, then, surely contribute to students’ learning and success, yet students’ reflections suggest that adequate time and project management are among them. Student B, for example, described the positive impact of the assignment’s structure on the pacing of her work:

“The components of the project, the Google Doc, photo journal, and presentation, seemed to work well together to organize our thoughts and pace the research so we did not save it until the last minute. Even though it was a busy week for me, the way the project was set up was very helpful in facilitating the assignment.

This overall experience has taught me a lot about research and organization. It has also given me valuable experience preparing and speaking in front of a class. This project was due during a particularly busy week for me. I had three large assignments due that week, this included, but I learned to cope with that, take things one step at a time, and I am proud of what we were able to accomplish.”

Student C’s comments illustrate how the expectations of a measured pace in the assignments were a challenge for him, but that they contributed to his effectiveness in research and in preparing for his final presentation:

“By the time I finished the research for my journal entries, I had all the information I needed to prepare for my presentation. It was nice to be able to share some of the interesting things I learned about. Meeting with [name redacted] a few times before we had to present was helpful, and gave us a chance to organize and practice. . . . The biggest challenge of this project was staying on top of all my journal entries. Trying to organize how to space them out in a way that made sense, while trying to balance all my other work, was difficult. I had to be extra careful not to forget about them and leave them all to the last minute.”

Articulating and modeling for students effective strategies for doing research over time can contribute to their success with organizing and processing large amounts of information, and help students to develop and sustain deeper engagement in their learning.

Students’ Attention to Process and Content

Our assignment aimed to foster students’ metacognitive awareness of their research process which contributes to students’ learning and is essential to digital literacy. Unprompted, however, students often struggle to engage at this level of critical self-reflection. In our first attempt with this assignment, they tended to focus only on amassing and describing their sources, essentially information dump. We hoped that students’ journals, then, would provide visible evidence of their research processes in order to better understand and reflect on their steps and their thinking. By bringing the process to the surface, we hoped students’ attention would shift beyond just the what of the sources and toward the why and the how of their sources, choices, and processes for richer critical thinking. Therefore, our analysis of student journals naturally aligned into two major categories: content and process. Content codes were used to identify journal excerpts in which students commented on sources in the following ways: summary, assessment, interpretation, connection with other information or personal experience, judgment, and reinforcement/challenge of preconceived notions.

In their journals, all students summarized sources with some frequency. For some, it was the focus of an entire post. For others, an initial summary was a foundation from which they built more diversified or reflective posts. In limited journals, we saw that students often paired the description or summary with their opinions or judgments. The following excerpt from Student I’s journal illustrates this common combination. He began with a summary of a source and then segued to his beliefs on the matter:

“After The London Riots, Prime Minister David Cameron wanted to censor social media, and ban rioters from communicating on these platforms. However, this did not pan out as well as he thought. So, it was back to the drawing board. In another one of Cameron’s plans, he wanted to censor emails, texts, and phone calls. According to the article, internet service providers would have to install hardware that would give law official real-time access to users emails, text messages, and phone calls. . . .

This also relates to the fact that Cameron still wants social media sites to censor their users. I think that this really impedes on a persons’ freedom of speech. If people are posting things on social media, they are public, therefore, they can be seen by whomever. So for instance, if people were planning violent rallies on Facebook, authority members could see this, and stop it before it happened by sending troops to the spot of the rally. Still, this is a major shot at peoples’ freedom of speech, therefore, I do not think it is necessary to take away a persons’ right to post on social media.”

In robust journals, by contrast, students more often paired summary with meaning making—that is, they interpreted the sources and attempted to make connections between different sources or with personal experience, as in this excerpt from Student H’s journal:

“This article focuses on the government trying to control what is posted on social media sites like Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. November of the last year, the Russian government created a law that would allow them to blog any internet consent they deemed illegal or harmful to minors. The only website to resist was YouTube which is owned by Google. They removed one video that promoted suicide, but wouldn’t remove a video that showed how to make a fake wound, because YouTube declared it was for entertainment purposes.

However, when the Federal service for supervision in telecommunications, information technologies and mass communications in Russia went to Facebook and Twitter, they complied with the bans the government gave them. If they didn’t comply the whole site would have been banned from Russia. This source makes me ask was this law only created to protect minors on the internet? Are there other motives with this new law? Will they ban other content that may be appropriate but not agreeable with the Russian’s views? I want to look into what other sites or content this law has been used to ban. This source definitely gave me insight into more issues of censorship occurring in Russia.”

While judgment and meaning making both require students to interact with sources and insert themselves into the conversation, they require rather different levels of critical thinking and self-awareness. With judgment, as illustrated by Student I above, students took a stand or made a claim, often in ways that promoted or reinforced rather than challenged their assumptions. With meaning making, on the other hand, as illustrated by Student H above, students attempted to interpret, clarify, and probe sources. These are different ways of interacting with information. The latter requires a greater degree of critical awareness and self-reflection on the part of the researcher and, therefore, denotes higher order digital literacy.

Process codes were used to identify journal excerpts in which students described their steps, as well as their metacognitive reflection on those steps. They included searching strategies and behaviors, organization, source selection, information availability, use of assigned digital tools (i.e., Google Docs, WordPress, and Prezi), information needs, next steps, and collaboration with their peers.

In limited journals, students frequently described their research steps. In this excerpt, for example, Student O described transitioning from using Google to library databases in order to locate academic sources:

“After finding several newspaper articles on Google, I started to finally look at the academic journals using the library databases. I was shocked to find that there was not that much information about the internet censorship in Iraq considering it is a big controversy. The few articles that I did find did have a lot of useful information to begin sifting through. Looking at the articles from the database is much different from Google because you can read the abstract to find the significance of the article and if it is worth taking a closer look at. I read through some of the abstracts and found some great information from background to actual laws and regulation. Now that I found out so much more information, I need to read through all of the articles diligently and take notes.”

In robust journals, students described their steps, but many also elaborated on why they took those steps and the questions they raised. In the following example, Student F described her use of library databases to locate scholarly sources, but also reflected on her motivation for doing so, her strategy, and the connections between her past experience and her current research:

“For awhile, the only type of research [name redacted] and I had done was through Google. While this was extremely helpful in gathering information and background facts about the censorship in Russia, we thought it was important to ensure we got some information scholarly sources. Using the Trexler Library website, we searched multiple databases searching for information on cyber censorship in Russia. We used information we found in the articles on Google to get more information into our search.

While I know finding scholarly sources is important, I have not always been the biggest fan of database searches. I always get frustrated when I can’t find sources that match what I am looking for. However, after some research, I found some sources with great information. Although the sources we found on Google were from reputable news sources, sometimes using Internet searches does not always produce the most reliable information. We thought it would be a good idea to get started and use scholarly sources to not only gather new information, but to verify the previous information found.”

The student provided insight not only to her awareness of her information needs, but also how her past research experiences were shaping her current work. She also recognized her ability to overcome obstacles and the intellectual rewards of doing so.

Many students described their steps to organize their sources and their work. In robust journals, some also reflected on the ways their organizational practices helped or hindered their effectiveness in managing information and their project. The examples below illustrate this important contrast.

Excerpt of Student O’s journal illustrating organization:

“I printed out most of the article that [name redacted] and I shared in our google doc of research. I have spent the past few hours reading through all of the articles highlighting key points and writing notes for myself in the margins. The notes have different categories to help me organize the research that I have found such as laws, what’s banned, background, etc. I have found this organization to be very useful so far.”

Excerpt of Student M’s journal illustrating organization plus reflection:

“The most difficult part of this project was definitely the research process—I had trouble with the organization of information. I often go overboard in my research process, gathering more information than I need. Sometimes I go so far in depth that I have trouble keeping things straight in my head (even if these things are written down, it’s hard for me to retrieve the information in my brain because I get jumbled and confused due to the abundance of information). So, although organization was the most difficult, this process helped me find ways to organize information in an efficient and helpful manner.

Keeping things in a Google doc. was a great source for me. By compiling all of my research in one place (the Google doc.) I was inspired to work on the research process every day. I’m not sure why the Google doc. provoked me to work on the research process each day, but color coding my sources and breaking things down into categorizes inspired me to do my work (as corny as that sounds). I think part of the reason for this was because the research process felt less daunting when I worked on it a little bit at a time. By creating categories for myself, and working from the question posed in our rubric for the project, I was more able to deconstruct the process. Rather than spending 4 hours research in the library every week, I spent 30-40 minutes researching every day. This was a much better process for me than what I am usually used to doing. Also, I think there may be a chance that since the Google doc. was online, over time I logged onto my e-mail or Facebook I thought of the Google doc. (and it was in my bookmarks bar) which reminded me to work on it.”

Students in robust journals demonstrated more awareness and understanding of their processes. We also saw more evidence of students’ description of and reflection on more inherently metacognitive themes such as identification of their information needs, charting of their next steps, and rationales for the selection of information sources. The excerpts below show the reflection intrinsic in these areas.

Excerpt of Student B’s journal illustrating rationale for selection of information sources:

“I have learned a lot from the research we have done, not only about censorship in Egypt, but also about research in general. It is important to gather information from a variety of sources, and types of sources, to get a full perspective on the issue. We used some informational sources and some current event/popular sources. This allowed us to find out what was happening at the time of the protest and censorship in Egypt as well as the political aspect and how people felt about it.”

Excerpt of Student H’s journal illustrating description of rationale for selection of information sources:

“I’m at the point in my research where I have enough information to satisfy the requirements for this project. I now have to figure out which information is relevant and which is not, what information should go into the presentation? Do we pick information that just covers the surface of all of our research or do we choose to be more specific and go into depth on one topic? I find all the information important and interesting, so how do I pick? I’m going to look at the most reoccurring themes and terms. Organize the content by those subjects and use that in the presentation. My reasoning behind this, is if this the more popular content among different sources than this must be what is more important.”

In limited journals, then, we saw students engaged primarily with specific tools and practices. In robust journals, by contrast, we saw students negotiating the bigger picture of their project. These students reflected on their choices, discussed their place in the project and in the larger information ecosystem, and generally moved toward more analytic thinking. Such awareness and reflection are crucial to digital literacy development.

Students’ Identity and Agency as Digital Learners

When we first implemented this assignment, we noted that students lingered most comfortably in information-seeking mode and struggled with critical analysis and comprehension of the information they were gathering. Recall that our purpose was to integrate and implement digital tools in ways to help students move beyond information-seeking mode to adopt more critical analytic habits and more advanced digital literacy practices. We were especially interested in the possible uses of digital technologies and pedagogies to help demystify research practices for students so that they might identify as researchers. Our goal was to leverage the collaborative, social, and public affordances of digital tools to make research practices more visible. In this iteration, then, we examined journals for instances where students explicitly located themselves within their research and identified themselves as engaged in and driving their research processes. We also included moments where students conveyed their feelings about their research processes—in short, their affective response.

Because we emphasized both the process and product of student research, it was important to pay attention to students’ subjective experiences along the way. We structured the assignment to empower students’ digital literacy practices. As discussed above, students did describe feeling more organized and less overwhelmed with this research project compared to prior experiences. However, we found very little evidence of students overall using their journals to reflect on their identities as researchers. There were little or no differences between robust and limited journals in this category. We did see a difference in students’ remarks concerning their research paths and next steps, though. Students who produced robust journals more often voiced where they were in their research and where they were headed. In this way, they conveyed a sense of self-direction and control over their work.

Students occasionally reflected in their journals about how they were feeling about the research project. This was true in both robust and limited journals. The following excerpts illustrate such instances of affect.

Excerpt of Student M’s journal illustrating description of anxiety:

“I have also included a screenshot of all the tabs I have open on my computer. This is somewhat out of character for me, which is why I thought it would be important to document. Usually, I can’t have more than 4 tabs open at a time or I start to feel disorganized which sometimes makes me anxious. On this particular evening I have so many tabs open they don’t even all show up on the bar itself. These tabs picture the sources I am pulling from while creating my Google doc. The Google doc. is seriously helping me so much—it’s a great organization tool and it’s helping me understand my information in a really efficient way.”

Excerpt of Student A’s journal illustrating description of confidence:

“We were extremely confident and knew that we were talking about.”

Excerpt of Student B’s journal illustrating description of feeling overwhelmed:

“So far, it has been a bit daunting to start finding articles that have good information to use for the project.”

We are wary of conflating students’ affective statements about their research with self-conscious identification as researchers. We do think it is important, though, to note these instances as part of the meaning-making process. The journal provided space for students to give voice to what it feels like to practice research, thereby making public what often remains hidden in undergraduate research.

Research practices are situated in environments, both online and offline. One of the most important choices students make about their research is where it takes place. Our assignment asked students to be attentive to the “spaces” of their research. We asked students to focus on space in the first journal post by reflecting on, describing, and providing photos of their ideal research environments. Our aim was to encourage students to develop awareness that research is situated in contexts and that, to certain degrees, students can make choices that shape where research happens. When students reflect on the place of their research, they locate themselves in place as researchers. There was no difference between robust and limited journals in this category of reflection.

In this excerpt, Student A responds to that initial prompt:

“My ideal place to do research is in my room. It is the only place where I get all of my work done and efficiently at that. I’ll usually play soft music in the background for me to listen to so I don’t get bored while I’m doing my research. I get my work done best when I’m doing it on my own, in my own space, and on my own time. I like to be in control of my environment and if I’m not, I’ll struggle to get my work done. I also like to have a coffee and a water nearby in case I need a drink. When I start my work, I usually have 1 bag of pirates booty or smartpuffs to kickstart my brain and my work. Below is a picture of my desk. Unfortunately, my desk is smaller than it’s been in the past, but it still gets the job done. I’m able to spread out my work as much as I want.”

Beyond the first required prompt about the places where student research happens, we found additional instances where students reflected on the environments of their research. The first post calling students’ attention to place likely helped to train their awareness on this theme later in the project. The following excerpt is from Student M, who paid continuous attention to the contexts of her research throughout the project:

“This has more to do with my working environment right now than my research, but right now as I am doing work my three roommates are in the midst of watching Gilmore Girls (I got their consent to post this picture). I am surprised that I am able to work in this environment, and to be totally honest, I think a lot of the reason is because I do not feel anxious about this information. I know that I still have a lot more research to do and a lot more work on my plate, but rather than finding this overwhelming I am genuinely excited to find a way to put together my information about North Korea so that it makes more sense to me and makes sense to other people.”

Student M’s lack of anxiety stemmed from her ability to control the place and pacing of her research. The excerpt conveys her thoughtfulness about where and when she was doing research. Moreover, it shows her enthusiasm and intention to meaningfully develop her research to benefit her own learning as well as her peers’ learning. Rather than being adrift in a vast sea of information, wading through sources, an awareness of research as situated helps anchor digital literacy practices.

While we understand affect and place as indicators of students’ awareness of themselves as agents within a research activity, there are notably few instances in students’ journals where they explicitly identify themselves as researchers. The following remarks illustrate this infrequent theme.

Excerpt of Student K’s journal illustrating description of feeling like an expert:

“It was also an interesting experience presenting on a topic that no one else in the class had knowledge on besides us, so it made us seem like the experts of subject matter.”

Excerpt of Student P’s journal illustrating description of researcher identity:

“Personally, I try to eliminate all distractions while I’m doing research. Depending upon how pressing the assignment is, I sometimes disable texting and prevent my computer from allowing me to go on Facebook. Ideally, it would be nice to have a private office with a door, but at college, that isn’t really realistic.”

Excerpt of Student Q’s journal illustrating description of connection of research to becoming an informed citizen:

“Researching North Korea’s internet connectivity policies was especially helpful to me in analyzing how our own policies in the USA might parallel. This may help me recognize the consequences of certain laws passed, and ultimately will make me a more informed citizen and voter.”

Beyond research “skills,” our assignment hoped to promote the development of students’ metacognitive awareness of their abilities to effectively engage in research activities using various digital technologies. This includes identifying paths and next steps. When students described their current and future research paths they were locating themselves in the research. Students did not use their journals to explicitly reflect on their development as researchers, but they did frequently identify in detail plans to advance their research. This occurred more frequently in robust than limited journals.

Excerpt of Student H’s journal illustrating description of next steps:

“This time difference has me questioning the relevance of this source and how to related it to my more current sources. Although it is helpful to understanding the background of Russian Internet, I find some of the information contradicting to the current information I have found. From here I think I need to look into more sources about classifications and see if there are more recent publications on this subject.”

Excerpt of Student Q’s journal illustrating description of next steps:

“From here, I think I would like to find out the exact specifics on the restriction imparted on North Koreans in regards to the internet, and look into exactly what the distinctions are between internet users and non-internet users in North Korea (whether it is determined by class, political position, or both). Furthermore, I want to investigate how these restrictions might impact foreigners visiting the country, and how the internet restrictions may also be stemming any information leaks coming from North Korea.”

In these posts, and others like them, students conveyed awareness of where they were in their research processes. They commented on the value and limits of their current searches and sources. They suggested what they needed to do or find next to advance their projects. Often in these posts, they articulated next steps in response to a particular limit or gap in knowledge that they had identified. Such reflection indicates to us an awareness of research as an iterative process, where a student can connect their current information seeking and analysis to their future activities.

Application to Practice

Our analysis guided us to make further assignment revisions for fall 2015. (See Appendix B for the revised assignment.) First, it was clear from our analysis that there was opportunity for us to increase the transparency of the project goals and purposes. We were more intentional in articulating these goals both in the written instructions and in our class discussion of the assignment and its elements. We spoke with students about the value of metacognition and our attempt to direct and focus their awareness in the research process. Second, we recognized that students who used the guiding questions were able to dig deeper and demonstrated stronger learning outcomes. Therefore, not only did we more emphatically urge students to employ the prompts in their journals in fall 2015, we also added new prompts and organized them in two categories (content and process) to better motivate their metacognitive awareness. The table below shows the revised prompts.

| Content (commenting directly on sources) | Process (commenting on your research steps, struggles, goals) |

| Describe the source. | What led you to this source(s)? How did you get started? |

| Why does this source matter? | What questions does the source raise for you about your research process? |

| What questions does the source raise for you about the subject matter? | Where does this source lead you next? |

| How does the source contribute to other knowledge or connect to other information? | How is the environment of your research impacting your work? How are you using digital tools to promote your development as a researcher? |

| What voices or perspectives does the source include? exclude? | Take stock of your progress to date. How does it look to you, from a bird’s eye view? |

Finally, we saw that students who published to their journals inconsistently also demonstrated a lack of engagement with sources and reflection on process. We therefore modified the assignment to make consistent pacing a formal expectation for the project and included it in the evaluation rubric. (See Appendix C for rubrics.) By making this change, we made the benefit of pacing extended research projects more transparent to students. Our future analysis will consider the impact of these changes on student learning outcomes.

Conclusion

The rapid growth of digital technologies and their integration in higher education is spurring conversation about what it means to be literate in the digital age. On a number of liberal arts campuses across the US, educators are asking, what does “the digital” mean for liberal arts education (Thomas 2014)? Some are now speaking of the Digital Liberal Arts (Heil 2014). Our case study contributes to a growing interest in understanding what digital literacies look like and how these abilities and practices can be developed to enhance learning in the liberal arts.

In our work, we saw students grappling with and frustrated by the challenges of information overload online and offline. While information overload may be an issue, it is a well-worn tendency to blame technology for young people’s deficiencies as learners and citizens. As educators, we must design digital pedagogies that create opportunities for students to navigate this complex environment. The digital pedagogies we are developing begin by shifting the locus of agency from technology back to our students, empowering them to manage the multiple contexts of information they traverse in their learning. By integrating digital tools in research projects that foreground pacing, metacognition, and process, we can help students develop their agency and identities as researchers. This agency is central to what it means to practice digital literacy.