As a leader in what is called the Digital Liberal Arts, we at the University of Mary Washington are facing the unique challenge of archiving our early digital output, namely, UMW Blogs. Started in 2007, UMW Blogs contains 11 years of digital history, learning, and archives. Although we are best known today as the birthplace of Domain of One’s Own, UMW Blogs was a testcase for showing the viability of such a widely available online platform for faculty, staff, and students.

After three years in which Division of Teaching and Learning Technologies (DTLT) staff and a few UMW faculty experimented with blogs in and out of the classroom (Campbell 2009, 20), UMW Blogs launched in 2007. It provided the campus with a WordPress installation that allowed any student, faculty, or staff member to get their own subdomain (e.g. mygreatblog.umwblogs.org) and WordPress site, administered by DTLT. Since then, the 600 blogs of 2007 has grown to over 11,000 blogs and 13,000 users as of 2018! Each site has any number of themes, plugins, and widgets installed and running, creating a database that is exponentially larger and more cumbersome than the user numbers suggest at first glance.

The viability and popularity of a digital platform available to the UMW community convinced the administration that we should be providing faculty, students, and staff not only with a space on the web, but with their own web address, hosting capabilities, and “back-end” access to build on the web beyond a WordPress multisite installation. Domain of One’s Own was born, where anyone with a UMW NetID could claim their own domain name and server space on the web, and where they could install not just WordPress, but also platforms like Omeka, docuwiki, or even just a hand-coded HTML website.

As a result, we now have two “competing” platforms—one legacy, one current—to administer and maintain.

Maintaining UMW Blogs today can be quite a challenge, and as the administrators we frequently alternated between idyllic bliss and mass panic. It’s not very heavily used (most users have moved to Domain of One’s Own instead), but when something does go wrong, it goes really wrong, bringing down every site on the system. And with a number of sites that haven’t been updated since the twenty-aughts, there are many that are poised to cause such problems: too many sites using too many outdated themes and plugins, leaving too many security vulnerabilities, and impacting the overall performance of the platform.

And while there was the initial expectation that the sites would be left up on UMW Blogs forever, the changing nature of the web and our understanding of digital privacy and data ownership has evolved as well. We have an open, online platform featuring works by former faculty and students that are over a decade old, many of which are inaccessible to the original creator of the content to delete. Content they may no longer want on the web. How do we balance preservation and privacy?

Of course, we can’t just pull the plug—well, okay, we could, but for many faculty, this would be unacceptable. Some of our faculty and students are still using UMW Blogs, and many of the sites no longer being maintained are important to our institution and its history—whether it’s an innovative (for its time) course website, an example of awesome student collaboration, or an important piece of institutional history. Former students, as well, may still be using content they have created on UMW Blogs in their job search. We want to ensure the UMW Blogs system works and that those important pieces of our institutional history and students’ intellectual property don’t become digital flotsam.

With that in mind, DTLT in collaboration with UMW Libraries have embarked on a major project to ensure the stability of our legacy system and the long-term preservation of UMW’s digital history. We are going to chronicle some of those efforts, both for the benefit of the UMW community and for those at other institutions who find themselves in a similar situation, or soon will.

Outline of the Problem

UMW Blogs contains some stellar content. A group of students (some of whom are now UMW staff) catalogued historical markers and other landmarks throughout the Fredericksburg/Spotsylvania area, mostly from the Civil War, providing important historical context. A student wrote love letters to his girlfriend at another university regularly for several months, leaving her coded messages and invitations to dinner dates (“don’t forget the coupon!”). Two colleges on campus hosted their Faculty Senate sites there. Student government leaders (and campaigns) hosted sites on UMW Blogs. And there are historical sites from many student clubs, activists, and research groups. And who can forget Ermahgerd Sperts, or possibly the most creatively unimaginative username: umwblogs.umwblogs.org.

While most faculty, students, and staff have migrated to Domain of One’s Own (DoOO), there are always those who remain on the the platform they are most familiar with. As a public liberal arts, teaching-intensive institution, many upper-division courses are only taught on a three-year rotation, meaning that course sites built in UMW Blogs remain inactive for two or three years until the course itself is once again offered. While the course sites could (and often eventually are) migrated into DoOO, the way that faculty and students then interact with those sites inevitably shifts, causing some degree of anxiety from faculty members, who thus delay the migration process.

In other words, in the faculty’s mind, if it isn’t broke, don’t fix it. Except, of course, it does break. Often. Leaving their course sites down.

In addition to valuable contributions to UMW history, scholarship, and archives, UMW Blogs also contains about 700 sites that were last updated on the same date they were created. (“Hello, World!”… and nothing since.) A number of sites have “broken” since they were last maintained, mostly as a result of using themes and plugins that have not been updated by their developers to retain compatibility with upgrades to the WordPress core platform. And then there are sites that, while valuable to some at the time, have been neither updated nor visited in a long time. This leaves broken and vulnerable sites, compromising those who are currently using the platform.

One of the challenges we are facing in the process of archiving the sites is the ethos under which the project was created, of openness and experimentation. The original Terms of Service for UMW Blogs reads:

UMW Blogs is an intellectual and creative environment, owned and maintained by the University of Mary Washington’s Division of Teaching and Learning Technologies. Users of the system are expected to abide by all relevant copyright and intellectual property laws as well as by the University’s Network and Computer Use Policy.

Users are encouraged to use UMW Blogs to explore the boundaries of Web publication in support of teaching and learning at the University, with the understanding that UMW may decide to remove at any time content that is found to be in violation of community standards, University policy, or applicable federal or state laws.

As participants in a public Web space, users must also understand that the work they publish on UMW Blogs generally may be browsed or viewed by anyone on the Web. Some features are available to users who wish to protect content or their own identity. Information about protecting content and/or your identity within the system can be found at the following address:[1]

While the TOS capture the ethos and spirit of UMW Blogs and prompt users to think about privacy, they don’t prompt users to address their own IP and copyright. This oversight is partially a reflection of the approach to the Web as open. Nevertheless, it leaves us, now, wondering what we can actually do with student work, former faculty and staff work, group blogs, long-term collaborative projects between faculty, staff, and students.

The intention was always that copyright would remain with the creator of the content (which was made explicit in the Domain of One’s Own Terms of Service). But as we archive sites, we have encountered a number of issues regarding whose permission we need to move these sites into the (public) archive, to which the original creators will no longer have access. This is particularly difficult for collaboratively created sites, where contributors to the site are not owners of the site.

There’s another related issue that has been weighing on our minds. Past members of DTLT (none of whom are still administering the platform) told users that their UMW Blogs sites would be hosted in perpetuity, but that presents a major data ownership and privacy issue. The internet is a different place than it was in 2007. According to Paul Mason, the entire internet in 2007 was smaller than Facebook is today (Mason 2015, 7)! And that’s to say nothing of the changing ways in which we view our personal data, even our public creative work, since GamerGate, Ferguson, and Cambridge Analytica. And as the birthplace of Domain of One’s Own, UMW (and DTLT in particular) has focused increasingly over the past decade on the ownership aspect of writing and working on the web—empowering students to make critical decisions about what they put on the web, what they don’t put on the web, and what they delete from the web.

We’ve also received a number of requests from alumni asking us to remove their blog from UMW Blogs, to remove a specific post they created on a faculty course site, or even to remove specific comments they left on a classmate’s blog as part of an assignment. We are well aware of the vulnerabilities that working in public can create, as well as the ways in which we as people change and grow, leaving behind aspects of the (digital) identity that we once shared with the world.

And so, beyond the need to streamline the platform, we think it’s important that we take the initiative to remove old content from our public platform, and to pass it along to former students and faculty so they can decide what should be public and where it should be hosted.

After everything is archived locally and before anything is deleted from the platform, DTLT will be reaching out to those former students, faculty, and staff, letting them know our plans, and providing them the opportunity (and documentation) to export their data and preserve it publicly or privately, in a place of their choosing. This not only helps those currently on the platform have a better experience, but it helps our former community members once again reflect critically on their public digital identity and take a bit more ownership over their data and what’s done with it.

As proponents of “digital minimalism,” we often tell our students and colleagues that what we delete is as important a part of curating our digital identity as what we publish. We want to encourage students (and faculty and staff) to think about how large a digital footprint they are leaving, and help devise strategies everyone can use to minimize traces of themselves online. And our freedom to delete increases our freedom to experiment. As the attention economy and algorithmically driven content discovery have radically changed the internet since the early days of UMW Blogs, it’s worth rethinking both what we as an institution hold onto, and what we as individuals decide to keep in public venues.

Another challenge was that at the start of this project, we at UMW did not currently have any policies governing data storage, collection, and deletion. Alumni could keep their email addresses, the only time we ever deleted a course in the LMS was when we moved from one to another, and we do not have a enterprise-solution cloud-based shared digital storage space. We were starting from scratch.

The Process, DTLT

We identified over 5000 blogs on the platform that have not been updated since 2015 or earlier, are not administered by any current UMW community members, and have either not been visited at all in the last two years or have been visited less than 100 times in the entire time period for which we have analytics. That means essentially half the platform is inactive and no longer providing benefit to users, but is also open to vulnerabilities or “bit rot,” which can cause problems for the active sites.

However, some of the inactive sites we identified are also important pieces of institutional history. After analyzing the metadata for all 11,333 sites in the UMW Blogs database, we identified a list of over 5000 blogs that meet all of the following criteria:

- The blog has not been updated since Jan 1, 2016.

- None of the blog administrators are current members of the UMW community.

- The site has either not been visited at all in the last two years, or has logged fewer than 100 visits all-time.

We then went through the entire list to identify sites important to our institutional history, as well as course websites that are less than five years old. (Some courses are offered every three or four years, and having relatively recent course websites live can be useful for faculty and students.) These are sites that we either think should be kept on the platform, or—more likely—that we think would be good candidates for UMW Libraries’ new Digital Archive. The latter will create a flat-file archive (a website with no databases or dynamic content, only HTML and CSS code) that will be far more future-proof and less likely to just break one day.

Now, we didn’t visit all 5000+ blogs manually! Rather, we looked carefully at the metadata—site titles, the person(s) attached to the sites as administrators, the administrator’s email address, and the dates the sites were created and last updated. This told us if the site was created by a student or faculty member, and if the site was a course website, collaborative student project, personal blog, etc. We identified almost 300 sites from this collection which we did check manually, often consulting with each other about them, before deciding on the 62 of these 5000+ sites that were important to keep public or submit to the UMW Digital Archive (more on that process below).

In the end, we determined that of the 11,333 blogs on the UMW Blogs platform, 6012 of them were important to keep actively published on the web (including about 50 which would best serve the UMW Community by being frozen in time and preserved publicly before “bit rot” and broken plugins bring them down). The other 5321 blogs, many of which were important in their time, are ready to be removed from the platform.

To be clear, we’re not talking about just deleting them! We are working with our hosting company, Reclaim Hosting, to create a flat-file archive and a WordPress XML export of each of those blogs, which DTLT will retain for 2 years before permanently deleting them. We are also preparing to email the administrators of those sites to let them know our plans so they can download their content before we remove anything from the platform (or, worst-case scenario, ask us to email them the backup archive after we purge the platform). But ultimately, it is important for the health of the platform to streamline the database and focus on supporting the more recent and active sites.

Through this process, we also identified a number of faculty and staff “power users” of UMW Blogs—those people who had more than 10 sites on UMW Blogs or had created a course site on the blog within the last two semesters. Once that handful of faculty were identified, we reached out to them to schedule one-on-one meetings with a member of DTLT to discuss the options for their UMW Blog site: deletion, personal archive, library archive, or migration to personal subdomain.

This was, admittedly, a fraught process for some of the faculty; these sites had become important and significant resources, examples, and case-studies of the viability and ultimate success of working openly on the web. They were sometimes years in the making, informed by countless hours of student and faculty work. To come in and say, “These sites aren’t viable in this space anymore” is intimidating.

One advantage of targeting the “power users” first is that we interacted frequently with these faculty members on a number of other projects, and thus had already developed a relationship with them, not to mention an understanding of their values, their work, and their pedagogy. We decided collectively which DTLT team member would work with each individual faculty member based on past relationships and interactions. We weren’t cold-calling these faculty; we were approaching colleagues with whom we had previously collaborated. Thus, we knew better how to discuss the issues with each individual faculty. While time consuming, we built on our relationships to tailor each interaction to the specific needs of the faculty member, allowing us to better explain and recommend options for their UMW Blog sites.

Explaining that our goal is, in fact, to preserve these websites in a more sustainable format, in order to celebrate and highlight their importance and significance to faculty, is key. We also want faculty to take more control over their data and their sites, understanding better how WordPress works and how the archival process will be of benefit to them. No technology, no matter how advanced, can survive this long without a lot of help, a lot of work, and some hard decisions about how we are going to invest our time, energy, and monetary resources.

We worked with faculty, then, to create a list of sites on UMW Blogs and categorized them based on how they wanted them to be preserved. Once that list was created and finalized, we passed the information along to the relevant people, including DTLT and UMW Archives staff, to make sure that all sites ended up in working order where they were supposed to be. When moving sites to Domain of One’s Own, we often had to replace themes and plugins, so that while the site might not look the way it did when initially created, we tried to ensure it would still retain its original functionality. The static library archive preserved the original link and function of the site in a static file.

The Process, UMW Libraries

UMW Libraries has been archiving the University’s web presence for several years now, primarily with established, automated web crawls and the occasional manual crawl to capture historical context during a special event, such as a university presidential inauguration. Our focus has been on archiving institutional sites, such as the main website, social media, UMW Athletics, or UMW News. Despite this effort, we were often missing the individual stories of the campus community.

We have a fantastic scrapbook collection in the University Archives. Stories from UMW (or MWC) students across the decades. Though students are still creating and donating scrapbooks, many are recording their college experience online, through Domain of One’s Own or UMW Blogs, rather than on paper. We also have detailed records of university business, such as meeting minutes, correspondence, and publications. The vast majority of this information is online today, with blogs or other platforms used to keep notes on committee work or to provide transparency on important campus issues, such as faculty governance or strategic planning. We must be proactive in not only preserving but providing access to these records for future students and researchers.

The UMW Archives appraisal process is an important step in beginning to archive this material. We not only need to make sure that the websites and digital projects we collect fit within our collection development policies, but we must also be confident in our abilities, through both technology and staff power, to preserve and provide access to the material we agree to accept. To help us with this process, we developed a set of criteria for appraisal:

- Scholarship that is new and impactful in its field.

- Highly innovative technical and/or creative aspects.

- Content that complements existing archival collections and subject areas of emphasis.

- Content that documents the history, administration, and/or culture of the University.

- Unique content that supports the research and curriculum needs of faculty.

- Content created, owned, or used by university departments, faculty, or students in carrying out university-related business, functions, or activities.

- Compatibility with SCUA’s preservation software.

- A faculty member’s statement of support for student-created websites.

This set of criteria will help us work through lists of current websites to determine what would be best suited for the UMW Archives. It is also published on the library website so that faculty, staff, and students can read through the list and determine if their website will be a good fit for the library’s collections. However, even if a UMW community member is unsure of where their website belongs, our hope is that the broad guidelines will encourage them to contact us and start a conversation. Even if a suggested website is not acquired by the archives, DTLT and UMW Archives staff will work with the creator to find other alternatives for migrating or archiving their content.

The lists of current websites that we are combing through and appraising do not contain the thousands of websites that DTLT started with on this project. For example, we removed from consideration sites that were created but never built out, don’t have any content, haven’t been accessed, etc. Other websites were also included because they were listed in previous university publications or suggested by a colleague. Our initial list of potential websites to archive is not all-inclusive, and it will be a continuous process as more URLs are recommended or discovered.

After websites are selected for archiving, the very important step of requesting permission follows. While the University Archives actively archives institutional websites, such as UMW Athletics or UMW Social Media, we feel strongly that we must receive permission before archiving individual blogs, websites, and other digital projects. DTLT and UMW Archives work together to reach out to the community to request permission from all creators and contributors of items that we want to archive. For those submitting archive requests, the copyright permission statement is published on the library’s website so that anyone can read and understand the terms before submission. Even if a faculty member recommends a website for archiving, the student still must provide permission before archiving takes place.

If permission is received to archive a website, the crawling can begin! UMW uses three tools for archiving websites: Preservica, Archive-It, and Webrecorder. Each web crawl is manually initiated by staff and student aides, as well as checked over for quality control after the crawl is complete. The crawl creates a WARC file, which is uploaded in the library’s digital preservation system. A metadata record in the form of Dublin Core is created for each WARC file, which includes creator(s), contributor(s), and two to three subject headings. Library staff used “Descriptive Metadata for Web Archiving: Recommendations of the OCLC Research Library Partnership Web Archiving Metadata Working Group” to help determine metadata guidelines, in addition to local, unique needs (Dooley and Bowers 2018).

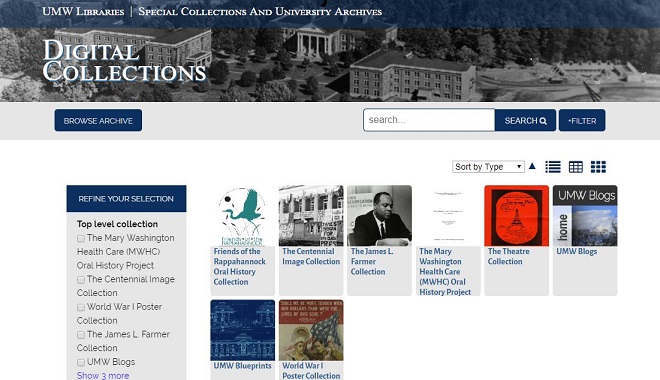

The final component to the archiving process is making the archived websites accessible. Once a WARC file is created and metadata is applied, the archival item is published in Digital Collections, the library’s digital preservation and access platform. Users of the platform are able to locate archived websites through search functions that use both metadata and full-text. The websites render within the browser itself, so users can navigate the website as it existed at the time of capture.

Conclusion: Further Challenges, looking forward, plan for it

This is only the beginning of a long process of preserving and protecting our legacy platform, UMW Blogs. The platform was a launch pad for Domain of One’s Own and put UMW on the map for innovative digital learning. At the time, there was no precedent, no best practices, no road map, no rules. Now, we hope the lessons shared in this essay help schools trying to maintain their own legacy, open, digital learning platforms.

Moving forward, we will likely confront similar issues with Domain of One’s Own, particularly concerning what we should preserve in our library archives. We are developing a process for students, faculty, and staff to submit a site for preservation consideration. But given the ethos of DoOO—that the work done on users’ website is theirs to do with as they like—we know there have already been some potentially important sites deleted, as is the prerogative of the user.

How, then do you balance the imperative to save, preserve, and keep digital artifacts of (potential) historical significance with the need for agency, privacy, and freedom of the student, staff, or faculty member to delete, let die, or decay? These are the questions we are now collectively grappling with, and will continue to moving forward.