In all of these decisions, I sought first and foremost to reduce the harm this course would cause my stressed students. In that mid-March moment, all signs indicated that this recently-designated pandemic would get really bad, and I didn’t want this class to make it worse. I balanced two competing pedagogical principles: the imperative to make this process as easy as possible and not produce unnecessary stress for the students, the other adjunct instructor who would be using my materials, and for myself; and the need to ensure that the students actually learned the material well enough that they would be able to succeed in the courses that follow this class. Or to put it more bluntly: I tried to prioritize care and reduce harm, without sacrificing rigor. The approach seemed to work, as more students successfully completed the class than during a regular semester.

In this essay I will articulate a theoretical framework for how I was thinking about these decisions as I made them and how I have come to understand these decisions in retrospect. At the time, I framed my pedagogical choices through a feminist lens as decisions about care and harm. Additionally, my familiarity with harm reduction principles gave me a loose framework to assess my decisions, destigmatizing illness and late assignments, and reducing the stress that this course would have on the already traumatized lives of my students, colleague, and myself. In retrospect, I will frame these decisions through trauma-informed pedagogy, a practice I only recently learned of.

Care and Harm

In recent years, many differently motivated organizations, movements, and individuals have deployed or theorized discourses of care, caregiving, and self-care. Just weeks before the pandemic took hold, both Social Text and The Sociological Review published special issues on radical care (Hobart and Kneese 2020; Silver and Hall 2020). Writing in the intro to Social Text, Hi‘ilei Julia Kawehipuaakahaopulani Hobart and Tamara Kneese juxtapose these competing claims:

On the one hand, self-care is both a solution to and a symptom of the social deficits of late capitalism, evident, for example, in the way that remedies for hyperproductivity and the inevitable burnout that follows are commoditized in the form of specialized diets, therapies, gym memberships, and schedule management. On the other hand, a recent surge of academic interest in care … considers how our current political and sociotechnical moment sits at the forefront of philosophical questions about who cares, how they do it, and for what reason.

Care means something very different for childcare worker advocates and Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop brand. Of course, COVID-19 only further exacerbated these tensions between corporate carewashing and the strain on essential care workers (Chatzidakis et al. 2020).

Care has an extended relationship to pedagogy. Nel Noddings articulated the feminist ethics of care philosophy to argue that care is a core element and value in pedagogical relationships between teachers and students (Noddings 1984). Her pedagogy of care has been very influential, especially in early childhood education, and has also been critiqued for its gender essentialism (Monchinski 2010). Others have explored the ways in which the theory would need to be transformed to be applicable to online education, with its shifts in contexts and relationships (Rose and Adams 2014).

My own engagement with care comes out of my work on Art+Feminism, an international community that strives to close the information gap about gender, feminism, and the arts on Wikipedia. Taking inspiration from Audre Lorde’s statement that “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare” (Lorde 1988), we design our events to support our participant’s minds, bodies, and psyches. We do this by constructing welcoming and accessible trainings, providing food and childcare at our events, and by maintaining a friendly spaces policy (Evans, Mabey, and Mandiberg 2015). We do this because we know that activism takes physical and emotional energy and is often met with resistance. We seek to care for the participants and to reduce the potential of any harm that may come to them (Tamani et al. 2020).

My work with Art+Feminism has caused me to think a lot about how to reduce the harm that our participants experience. It may be unconventional, but in that intense moment in March, I used my admittedly surface level understanding of harm reduction as a loose framework to assess my decisions. Originally articulated during the 1980’s HIV epidemic to describe needle exchanges, harm reduction is a public health theory that eschews an abstinence-only approach to risk and disease in favor of practices that minimize negative outcomes (Des Jarlais 2017). To be clear, I am in no way equating taking a digital media course in a pandemic with opioid addiction; the concept of harm reduction can be implemented in different circumstances. While harm reduction remains most frequently discussed in terms of drug and alcohol addiction or sex education, society has widely adopted many other harm reduction strategies: seat belt laws and rest stops reduce traffic deaths endemic to automotive travel; hard hats, bicycle, motorcycle, hockey and football helmets reduce serious brain injuries; life vests and fences around pools help prevent drowning; and sunscreen mitigates the danger of skin cancer inherent in being outdoors (UNAIDS 2017). During the pandemic, societies have encouraged social distancing, hand washing, and wearing masks to help reduce the likelihood of contracting COVID. These are forms of harm reduction: we accept that it is not possible for most people to completely abstain from interacting with other people and, for those that continue this inherently risky behavior, certain practices can help reduce the potential for physical harm (Kutscher and Greene 2020). Of course, these measures have not mitigated the pandemic’s significant mental health impact (Choi et al. 2020; Abbott 2021).

While it may be unconventional to apply harm reduction principles to the mental health impacts of the pandemic classroom, a small number of practitioners have discussed applying harm reduction principles to mental health (Krausz et al. 2014). While writing this essay I learned about social welfare’s use of trauma-informed practice to provide services that are sensitive to their clients’ traumatic histories. Trauma-informed practice is built around five principles: ensuring safety, establishing trustworthiness, maximizing choice, maximizing collaboration, and prioritizing empowerment (Fallot and Harris 2001). Educators have adapted these principles into a trauma-informed pedagogy in K–12 education (Thomas, Crosby, and Vanderhaar 2019), and more recently in post-secondary education—first in social welfare (Carello and Butler 2015), and to other disciplines in the wake of the pandemic (Imad 2020). At their core, these practices seek to minimize the potential for retraumatization and maximize students emotional and cognitive safety.

While I was motivated by discourses of care and harm, trauma is probably a more precise definition. I always enter the classroom with the knowledge that my students have already experienced trauma, as people living in an unequal society, whose divisions, imbalances and punishments are marked by the intersections of race, gender, and class. I knew that many of my students would be physically vulnerable, and the rest would be economically vulnerable. Most of my students hold jobs, many of which are full time. I knew that most of my students either work in parts of the service sector that would be deemed essential or in retail jobs that would be laid off or furloughed. They live at home with their parents, who are similarly vulnerable.

Thus, as I redesigned the course, I centered care by reducing the potential for harm and trauma that this course might cause my already traumatized students. I knew that the COVID-19 crisis would amplify and transform a task that would have previously been a productive challenge into a debilitating barrier to completing an assignment or the course. We had to get our way through the semester amidst a public health crisis, and I wanted to make sure I removed as many barriers as possible and reduced the stress that this course would have on my students, colleagues, and myself.

Digital Foundations Online

COM 115 Introduction to Media Environments is a one-credit, 7 ½-week course that introduces students to the basics of digital media production. It is required of all students in the Communications major at the College of Staten Island and is the prerequisite for all courses in the Design and Digital Media specialization. COM 115 is the only course in our program with a standardized syllabus used across all sections and instructors. I typically teach two to three sections a year, while the other six to eight sections are taught by adjunct faculty. During the second half of the Spring 2020 semester there was only one other section, taught by an adjunct instructor.

I developed the course alongside the Digital Foundations textbook I co-authored with xtine burrough (burrough and Mandiberg 2008) and maintain the wiki version of Digital Foundations, which is kept up to date with Adobe software releases. Like Digital Foundations, COM 115 integrates historical examples and the design principles of the Bauhaus into an introduction to digital media production. For example, in COM 115 students use the Josef Albers color theory exercises in order to understand the Color Picker tool, integrating history, aesthetics, and technique in the same lesson. While the course emphasizes design principles and techniques over software training, the class does function as the “Intro to Adobe” for our department. The Adobe Creative Cloud has developed a monopoly on design and digital imaging software in the creative industries and in the classrooms of students who aspire to enter those industries. Like all monopolies, Adobe extracts a hefty price—one that has become more unavoidable since they shifted to a subscription-only model.

In March, faculty from across CUNY converged on the usually quiet Media, Arts, and Technology Discipline Council group on the Academic Commons to participate in a thread titled “Moving production courses online for COVID // the Adobe problem.” Though media arts courses are well suited for online delivery, rapidly migrating a digital media production course to remote learning creates problems specific to the tools and techniques used in our software-based classrooms. This is not just a problem for this course, or for all digital media arts instructors, but for all courses that rely on fixed technology—especially those at underfunded public institutions like CUNY with students who have difficulty accessing fixed technology (Andre Becker, Bonadie-Joseph, and Cain 2013; Smale and Regalado 2017); as opposed to mobile technology like smartphones, fixed technology refers to desktop computers, printers, and other resources that are often only available to our students in computer labs.

My own experience piloting an online version of the class in 2012 confirmed this challenge. Because of a failure in the CUNY First registration software, very few of the students realized they were registering for an online course. Roughly half of the students dropped the class, and many of those that remained struggled to succeed because they were unable to access the necessary Adobe software. I made my decisions to ensure my students would not experience this kind of trauma as a result of my course.

Avoiding Adobe

I decided to not use Adobe software, opting instead to use two Adobe web app clones: Photopea and Designer.io. I made this decision by following my goal to prioritize care and reduce harm, without sacrificing rigor. I can say with confidence that this was the right decision.

At the time that I made the decision to use web apps, we did not know if our department’s Mac lab or the library labs would stay open—they did not. Nor did we know whether or not students would be able to access the Adobe software on their own computers—they were, because Adobe granted a special license, but we only learned this a week after the course began. I knew that if Adobe didn’t make that special license available, most of my students would not be able to secure their own copies of the software because of its subscription model’s substantial cost. Once it was made available by the school several weeks into the course, only a small percentage of the students installed it—the majority used the web apps, including all the students who came to video office hours.

Many of our students do not have easy access to fixed technology, and those that do have access to a desktop or laptop may not be comfortable installing software, nor may the computer be powerful enough to effectively run the resource intensive Adobe software. Because so many of our students lacked access to computing, CUNY made an emergency purchase of 25,000 Chromebooks and 25,000 Android tablets to ensure our students would be able to access online learning. Many of my students used these Chromebooks for the course. I chose to avoid the open source Inkscape and GIMP because of the difficulty of installing software, because of the uncertainty about the capabilities of the Chromebooks, and because their interfaces diverge from the Adobe software more than the two web apps.

The user interface for Photopea is almost identical to that of Photoshop, and Designer.io follows the principles of Illustrator though its interface diverges more. In Photopea, the menu item names are almost all exactly the same, in the same place, with almost identical iconography; in Designer.io the tools are very similar, if located in slightly different places. Photopea even exports the PSD format with layers. They aren’t exactly identical: for example, Designer.io a has a slightly different pathfinder tool, and intermediate tools such as unsharp mask are missing in Photopea. Neither has the kind of advanced features that the Adobe software has, but these are sufficient for an introductory class at the 100 or 200 level. Most importantly, these tools scaffold directly into using the Adobe software: the tools, menus and concepts are so similar.

Using these web apps was the right decision. I experienced very few difficulties with students getting set up to use the software, and it worked on macOS, Windows, and Chrome OS. While neither is set up for mobile use, both officially work on tablets, though they were a bit glitchy in my testing. Most importantly, I am confident that the students who will continue on to other 200-level courses in the program will be able to seamlessly move into the Adobe software.

A caveat: I cannot predict the longevity of these two websites. I couldn’t find much information about Gravit, the for-profit Canadian company that develops Designer.io. Confusingly, Photopea has a GitHub repository for “bug reports and general discussion” without any code, but “Photopea is not fully open-source.” I don’t know what their business models are nor if they have sufficient resources to continue keeping these tools up and running.

Another caveat: both Photopea and Designer.io are freemium web apps. They include advertisements, and up-sell pitches for their premium versions. Designer.io requires you to create a login. I’m conscious of the adage that “if you’re not paying for something, you’re not the customer; you’re the product being sold” (blue_beetle 2010). Working within my principles of harm and care, I felt confident that a few more ad targeting cookies were a lesser harm than not being able to access any software.

Asynchronous instructional design and learning experiences

Knowing that the pandemic was certain to destabilize my students’ lives, and their schedules, I chose to design an asynchronous course in order to prioritize care and minimize harm. I knew that some students’ lives would be completely derailed by the pandemic, but if I structured enough flexibility into the course so students could complete the assignments when their pandemic timelines allowed, I could reduce the potential that they would fail to complete the course. I used Blackboard as the platform for asynchronous videos, pairing these with video office hours during the regularly scheduled two-hour class period. As much as I detest Blackboard, I knew that my students would be using it in their other classes, and would be most comfortable there. In the best of times, I substantially but productively challenge my students when I use Wikipedia or the CUNY Academic Commons as the course platform (Davis 2012). In these worst of times, I feared a new interface would be harmful.

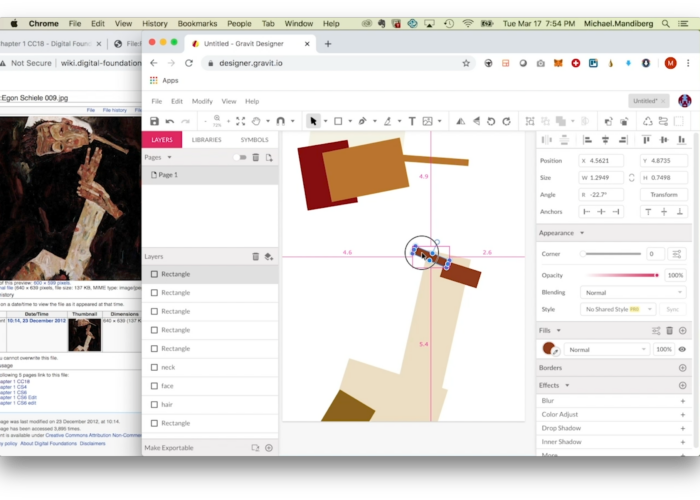

Video demonstrating Mac OS computer interface, with an image of an Egon Schiele painting in a small window at the left, and a larger Gravit Designer window with a composition of rectangles based on the painting.

Using the web apps, I made video demonstrations of each of the exercises we cover from Digital Foundations. I shared these videos with my students and the adjunct instructor via a public Dropbox folder, which also includes the course syllabus, and the text of each of the assignments; additionally I posted a Study Guide in preparation for the exam. In the principle of reducing strain for everyone, including my adjunct colleague, I shared all of my assessment and communication materials via a private folder. These materials included: quizzes and exam for Blackboard; exam text and individual images; and all emails and announcements. I decided to make the weekly quizzes for practice only, rather than grading them, in an effort to lower the stakes.

Course dynamics were starkly different from teaching this in-person, or as a synchronous online course. Essentially everyone was doing their own private effort. They had almost no interaction with each other. Trauma-informed pedagogy emphasizes communication between students, collaboration, and peer support, which were entirely absent from this model (Imad 2020). And yet, they were able to finish the course. Of the fifteen students in the course, one dropped, and one never completed any assignments, but the remaining thirteen completed the majority of the assignments and all of them passed. Of these, five came to my video office hours; one student came every week, two students came every other week, and the other two popped in once. Four of the students who never came to office hours were very self-directed and highly motivated, and maybe had some previous experience with digital imaging. The remaining four who struggled and never made it to office hours made clear that they were impacted by COVID-19.

In retrospect, I recognize that I fostered the trust and safety that trauma-informed pedagogy advocates by encouraging my students to keep their video off if they wanted, which they did. During video office hours I only saw one student’s face, briefly, when they pressed the wrong button when trying to share their screen. While some of my colleagues actively complained that they couldn’t see their students, I knew my students needed privacy. They have a right to not let their classmates and their professors see the inside of their messy bedroom, or the closet, bathroom where they retreated from their other family members to get quiet and privacy. I found I was able to build rapport with the five who came to office hours despite the absence of video; and maybe I succeeded precisely because I didn’t ask them for video.

Challenges

The course was not without challenges specific to the online format and the larger pandemic context. The main instructional challenge that I faced was in demonstrating resolution. We typically do this by scanning objects; we set the resolution on the scanner and analyze the image in Photoshop. Knowing they would not have access to scanners—I didn’t even have a scanner at home—I reframed the exercise on photographic composition, with the emphasis on printing the image in multiple resolutions so they could see the different print sizes. I should have seen this coming, but I falsely assumed that they would have access to printers, so I reframed the printing process with an emphasis on taking screenshots of the print preview interface, which shows how big the print is in relationship to the paper size. There were more hiccups: the “print actual size” option is not available in the default Windows tool, something that I didn’t know because I don’t have access to a Windows computer at home, so I worked with one of the students to figure out a workaround, and she made a video demonstrating it. Unfortunately, we did not find a workaround for Chromebooks.

The larger challenge, as expected, was that half of my students were mostly disengaged from the course. At the start of the course, I told the students that the course was self-paced, but they should try to do one chapter a week, and to have the first three chapters done by halfway through the course. At the halfway mark only half of the students had completed the three chapters, and I was worried. I spent a lot of time writing them to encourage them to complete the work and relied heavily on a College of Staten Island Student Affairs COVID specific “EDUCares” team that succeeded in reaching the students I could not get engaged. EDUcares’ mandate included checking in on unresponsive students, performing a hybrid wellness check/late homework reminder. I shared a list of students who had not responded to my emails with EDUcares, and they emailed the students on their non-CUNY email addresses and/or called them at home and in some cases on their cell phones. They were able to get responses from all but one of the students and all but that one student (who never responded throughout the course) completed the first three chapters shortly after. During these exchanges I learned what I suspected: many of them did not have internet access, were without a computer until they received a CUNY loaner Chromebook, or were sharing a computer with other members of their family.

Outcomes

Certain aspects of the course (and the knowledge they produce) were simply not possible in this format: when I teach color theory in person, we spend fifteen minutes of class looking at and describing the colors of the clothes that everyone in the class is wearing. By the end of those fifteen minutes, they understand that there really is no such thing as black or white and they start to see the blues and purples in the very dark grey they previously would have called black and the yellows and oranges in the 5 percent grey that they would have called white. That simply isn’t possible to do as a group, in this online format. It isn’t really possible to do it with colors on a screen, as these are so removed from their lived experience, and each person’s screen will have a different color profile. I tried to do it with the one student who came to office hours every week, and it took us thirty minutes of one-on-one discussion—it is very strange asking a student to describe the color of the computer they are working on and persuading them that it isn’t actually dark grey, as they claim, but rather is a very low saturation dark blue.

To speak more broadly, it seems so hard to do radical pedagogy online. The software is structured around the banking model of education (Freire [1970] 2000), except instead of the human instructor at the front of the classroom depositing knowledge into the students’ presumed empty minds, it is a video of the instructor. Paolo Freire would be sad to see this (Boyd 2016). When I teach this course again, I will try to work against that as much as possible. This is one place where I might have sacrificed too much of the rigor in favor of care and reducing harm.

On the other hand, I feel like more of the students demonstrated baseline competency in the techniques that we covered. More specifically: in a typical in-person class of fifteen students, two-to-four students fall behind and never catch up because they always came twenty minutes late, missed the first class, couldn’t complete assignments on time, etc. This format alleviated some of this problem. In a typical in-person section those two-to-four students per class sit for the final exam and still fail the course, but in this format everyone who took the final passed; the only person who did not pass the course, never completed a single assignment and earned a WU (Withdrew Unofficially) grade. In this online course, the students who struggled did show their limits: in the final exam they performed better than the typical students who sit for but fail the final exam in an in-person class, but worse than the students who had steadily completed assignments throughout the course. Overall, the cohort did as well or better than most in person classes on the hands-on section of the final exam.

This was an emergency effort. None of these students expected to take an online class. My adjunct colleague and I never expected to teach one. Despite this strained context, my decisions to prioritize care in order to minimize harm helped us all get through the semester, while preparing the students to succeed in future courses. Though our classrooms will “return to normal” some point—or whatever our new normal will be—our students will carry the trauma of this pandemic. I hope to continue this trauma-informed pedagogy of care, finding a new balance between reducing harm and maintaining rigor in what will hopefully be a less traumatic post-pandemic teaching environment.