“There’s no use trying,” [Alice] said: “one can’t believe impossible things.”

“I daresay you haven’t had much practice,” said the Queen. “When I was your age, I always did it for half-an-hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (1871)

Introduction

For first-year undergraduate students, college work can feel like the expectation to do the impossible. When confronted with projects that require original research, these students may feel ill-equipped to engage with unfamiliar techniques and may give up without even trying. If, by emulating Lewis Carroll’s Red Queen from Through the Looking-Glass, instructors can encourage students to practice believing in their ability to achieve “impossible” things, and create a situation in which it is acceptable to fail, students can begin to feel secure enough to try for the impossible.

In this spirit, our article details an undergraduate student research project titled “The Possibly Impossible Research Project,” a collaborative effort between the Baldwin Library of Historical Children’s Literature at the University of Florida and the Writing and Communication Program at the Georgia Institute of Technology. This article outlines a multimodal digital research project that provided Georgia Tech students with in-depth instruction into archival research processes while improving the Baldwin’s “Guiding Science” annotated bibliography. This assignment also offered students an opportunity to uncover and make meaning as researchers in their own right, and to distribute that new knowledge through public-facing digital platforms such as Twitter and Wikipedia. Overall, the project produced a meaningful collaboration among the undergraduate students, the course instructor, and the curator of the Baldwin Library, while contributing knowledge to the larger academic community. Further, it can serve as a model for engaging undergraduate students with archival research, analysis, and dissemination.

“Guiding Science” Bibliography Project

The contributions of women to early scientific discoveries and the dissemination of international scientific theory are still largely unknown outside of the fields of children’s literature and the history of education. In 2014, the Baldwin Library of Historical Children’s Literature was awarded an American Libraries Association Carnegie-Whitney grant to develop a digital annotated bibliography of women-authored science books for children during the long nineteenth century. As an ancillary to “Guiding Science: Publications by Women in the Romantic and Victorian Ages,” the George A. Smathers Libraries digitized 200 titles from the project to provide context to the bibliography and encourage use of these texts in teaching and research.[1]

One of the main aims of the bibliography project was to highlight the important—and often neglected—work of women to promote scientific invention, discovery, and the development of the scientific method. However, with the professionalization of the sciences from the home to the academy, the work of these women was ignored and, in some cases, maligned. As science formalized fields of study and work, women were pushed out of their work as lab assistants and translators of scientific theory. Since women could not receive any formal training in sciences (women were not allowed to attend universities in Great Britain until the twentieth century, and very few women were able to attend universities in the United States until then), they were relegated to the role of mere amateur. Their previous work as authors, educators, and partners in scientific discovery was forgotten or dismissed as being of lesser quality than that of their formally trained male counterparts.

In compiling the bibliography, the Baldwin Library curator, Suzan Alteri, identified titles, authors, and subjects in the library’s online catalog. Identifying subjects proved difficult since the many fields of science during these eras fell under the umbrella of natural history. In order to fully capture the scope of scientific endeavors, it was necessary to keyword search scientific concepts rather than broad science subject fields. In searching for titles to include in the project, Alteri discovered many anonymously written titles. Since the project had already identified many books written by women, Alteri began to wonder how many of the anonymously written titles were actually authored by women. Because of the enormous legal and social barriers to education, work, and full participation in society before and during the nineteenth century, books authored by women were often published anonymously so as to avoid derision, as Cheryl Turner noted in Living by the Pen: Women Writers in the Eighteenth Century (2012).[2]

In addition to the bibliography, Alteri felt it was necessary to add additional contextual information so readers would understand the time period and constraints under which these women were writing while also providing a better understanding of how science and science education developed in tandem. Since the project was rooted in the idea of discovering the hidden work of these women, Alteri believed one of the most important aspects of contextual information would be biographical information on the authors. Since most women did not receive a formal education until at least the mid-nineteenth century, how were they able to write so many crucial texts for science education? By tracing biographical details such as familial status, exposure to education through tutors, and other pathways to education, Alteri thought that readers of the bibliography would be better able to grasp women authors’ contributions to literature, education, and science. Moreover, compiling biographical details often uncovered interesting facts about how women’s writing was received by both the scientific community and how their entry into the public sphere, as writers, was viewed by society.

However, finding biographical information on over one hundred different women authors who wrote in the eighteenth and much of the nineteenth century was surprisingly difficult. While some writers, such as Sarah Trimmer, wrote numerous texts and are well-known for their contributions to early children’s literature, many women authors did not sign all or any of their books. This tendency to leave texts unclaimed was compounded by the fact that in British society of the time, vital record information was not regularly kept on daughters and wives. Since Alteri was working alone to compile biographical information, tracking vital record information would have been too laborious a process. Instead, Alteri opted to search the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and Wikipedia for biographical information. The ODNB was originally published in 1885 (and continuously updated) as the Dictionary of National Biography, a biographical listing of important peoples from Great Britain and its colonies. Wikipedia was used for the small number of American authors.

Searching biographical dictionaries by name yielded interesting results. For authors who had their own entries, summarizing biographical information was simple. For others, scant biographical information was discovered through more famous husbands and brothers. For example, a few sentences on Emily Taylor are contained in her brother’s entry, Edgar Taylor. As noted earlier, women writers often faced steep criticism for entering the public sphere of professional writing, and many simply published under their married names—Mrs. Thrope or Mrs. Brook—or signed their work as “A Lady” or “A Mother.” Alteri was able to cobble some information together by searching for male relatives, particularly if, as in the case of Mrs. Norman Lockyer, they were scholars of some note. A very small number of authors were able to be tracked through their publications, since most books of the time period contained the phrase “By the Author of…” Still, out of the 123 authors listed in the bibliography, fifty authors, or forty percent, were untraceable by these methods. Alteri was struck by how large the percentage was, but struggled with how to convey a partially successful recovery project to end users of the bibliography. For Alteri, and other scholars on the original project, it was obvious that the barriers to women’s education and participation in the public sphere in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were the result of sexist practices, but would people unfamiliar with children’s literature, women’s history, and feminist recovery projects understand the impact of having no information on a person except a copy of a book? By compiling biographical information on these women authors, it is not only their texts and ideas which are recovered, but their lives as well.

Undergraduate Research Collaboration

As chair of the Baldwin Library’s Scholars Council, instructor Rebekah Fitzsimmons of the Georgia Tech Writing and Communication Program (WCP) was familiar with the goals of the “Guiding Science” project and the curator’s struggles. WCP houses the core communication courses for Georgia Tech, including the two-semester composition sequence, and emphasizes multimodal communication through the WOVEN (Written, Oral, Visual, Electronic, and Nonverbal) framework. English 1102, “continues to help students learn how to communicate more effectively, but with a greater emphasis on research, argument, and applied theory. Instructors of English 1102 construct courses around intellectually engaging and relevant themes from science, technology, literature, and popular culture.” The course also encourages projects that “help students learn the role that research plays in formulating social and cultural ideas.” Inspired by conversations in the popular media surrounding the #MeToo movement and films like Hidden Figures (2016), Fitzsimmons felt students at an elite technical institute would benefit from a research project that not only highlighted the vast number of women involved in scientific discovery during the Victorian age, but also actively demonstrated the ways in which the accomplishments of those women were forgotten or actively appropriated by others.

Fitzsimmons and Alteri collaborated to design an ENGL 1102 course that would provide Georgia Tech students the opportunity to contribute original research to the “Guiding Science” bibliography. The resulting course was titled “The History and Rhetoric of Science Writing for Children” (syllabus available here). Students were asked to think through the ways rhetorical communities of science writing—especially those focused around education—changed given various historical moments, and the ways in which certain voices within those communities have long been privileged, ignored, or actively silenced. Students read children’s literature with scientific themes, including Charles Kingsley’s The Water-Babies (1862), Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden (1911), Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle In Time (1962), and contemporary (2011–present) science-themed picture books. Engaging with primary texts and secondary critical literature, classroom discussion touched on the historical transformations of “scientific” ideas about race, gender, evolution, astronomy, mechanics, health (physical and mental), professionalization, and science education from the Victorian age into the twenty-first century. In dedicating the research unit of the course to investigating the lives of these lost Victorian science authors, the students engaged with real world examples of Victorian women working in and writing about the sciences with academic rigor, creativity, and a dedication to educating young people about physics, chemistry, astronomy, natural history, hygiene, horticulture, home economics, and geography.

The course utilized Paulo Freire’s problem-posing education model within a Critical Digital Pedagogy framework, which encouraged the students to experiment, play, improvise, and fail as a part of the learning process. In their book An Urgency of Teachers: The Work of Critical Digital Pedagogy, Morris and Stommel (2018, 23) note that “Digital pedagogy calls for ‘screwing around’ (Ramsay) more than it does systematic study . . . digital pedagogy is less about knowing and more a rampant process of unlearning, play, and rediscovery.” By embracing this model of learning, the course was designed to empower students to interrogate the rhetorics of scientific discourse that would be relevant to most of their future careers in the STEM fields, while breaking the hierarchical model of the classroom to encourage students to collaborate with the professor and one another. This process helped the students to make meaning, including applying this work to their own professional fields and connecting their developing skills to future projects and goals.[3] In addition, folding original research into the course exposed students to primary sources in literature and research processes using special collections and archival materials. Since special collections and archives are often viewed as the laboratories of the humanities, many of the research methods used by scholars in special collections and archives mimic those used in scientific laboratories, particularly observation and testing.[4] In this case study, students began with observations about science during the Victorian age, developed questions regarding their chosen author, and then began to “test,” through interrogation, various sources for biographical information. As Anne Bahde (2011, 75) states, allowing undergraduate students to interact, even digitally, with primary sources can “provoke an unusual level of critical inquiry.” Primary sources are often neglected in many undergraduate courses either due to curricular time constraints or pedagogical biases that reserve primary source research processes for graduate students. However, Pablo Alvarez (2006, 95), and others, document how using rare books in the undergraduate curriculum can “offer new perspectives that can lead to original research.” Students are often more engaged with primary source material, either due to the uniqueness of the resources or their novelty as a relic of times gone by. Providing students with the opportunity to act as a professional researcher helps them become more responsible and empowers them to drive their own education. The focus on process and experimentation in this project allows students to work, sometimes for the first time, in a space without a preconceived notion of right or wrong answers and a shared sense of authority within the classroom.

“The Possibly Impossible Research Project” asked students to assist the curator of the Baldwin in researching the fifty female authors from the “Guiding Science” bibliography about whom she had been unable to locate sufficient biographical information. Each student was assigned one author and asked to research and compile enough information to complete either a multimodal Wikipedia article or a short textual biography to be posted on the “Guiding Science” website. Each student was given all the information Alteri had already compiled as a starting point, which might include lifespan dates, family information, known pen-names, or country of origin.

This assignment acknowledged from the outset that the chance of authoring any kind of public-facing biography might not be achievable. From the very title of the assignment, it was important for students to understand that the ultimate goal of the project might well be out of reach (as it was for the curator). Therefore, the assignment was structured to help students learn good research practices and goals, engage with various digital learning communities, and document their work with an eye toward process over final product.

The final project deliverable was a research portfolio, which permitted students to mix and match at least three of the following elements based on the information they found:

- Multimodal biographical article posted on Wikipedia

- Public-facing biography for the Baldwin “Guiding Science” website

- Bibliography of sources in MLA format

- Archived Twitter research journal

- Research narrative of 600–800 words

- Archived correspondence with librarians, scholars, archivists, or other experts

- Archived images

The assignment sheet and in-class discussions emphasized that while the ideal outcome of the project was a public-facing biography, it was possible that students could fulfill the required learning outcomes of the assignment and earn an A even if they could not complete this portion of the portfolio. Ultimately, the assignment sheet instructed: “Students should approach this project as a journey into the unknown. They should be prepared to make mistakes, get messy, and potentially come up empty-handed.[5] A large part of the project will include figuring out how to make failure and frustration productive, how to document a research process so that future researchers might benefit, and how to enjoy the research rabbit holes.”

Pedagogical Goals

This assignment focused on four major pedagogical goals. The first was content related: to have students engage with historical records and the rhetoric of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century scientific communities. The women represented in the bibliography project were talented, often prolific authors; many were also brilliant scientific thinkers and researchers in their own right. However, due to the social and political realities of the Victorian age, the vast majority of these women were denied opportunities to practice scientific inquiry in any professional sphere or were considered mere assistants in the scientific careers of male relatives such as a husband, father, or brother.[6] Prior to the Victorian age, scientific discovery occurred in the home, which could make it easier for women to participate. But the professionalization of scientific inquiry into academic fields developed rapidly during the nineteenth century. Ann B. Shteir (1997, 236) notes that burgeoning professionalization coupled with the restriction of women in public sphere created circumstances which instilled “more exclusionary relations between women and science culture.”

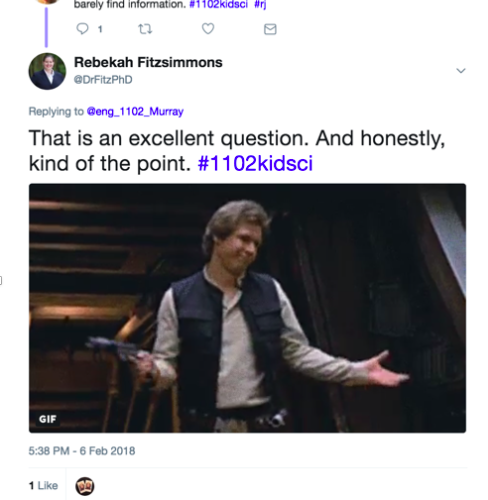

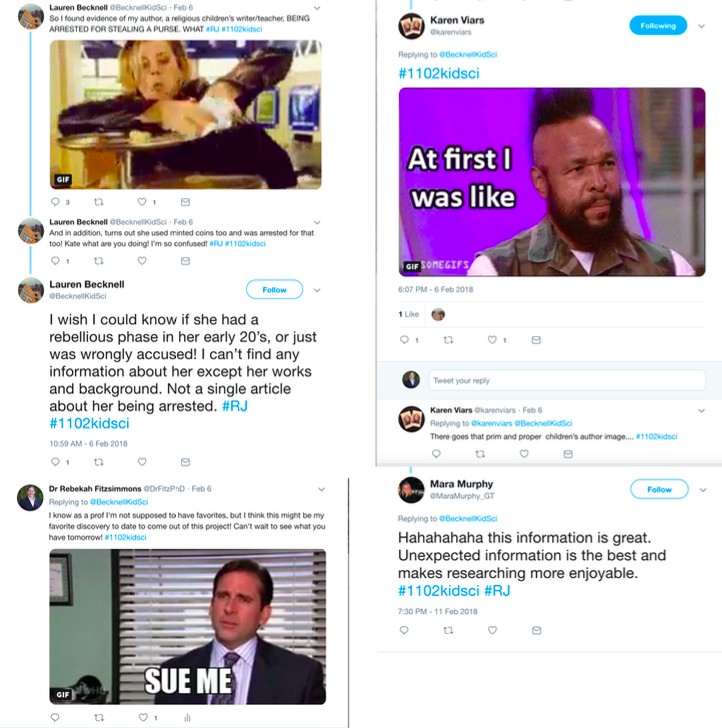

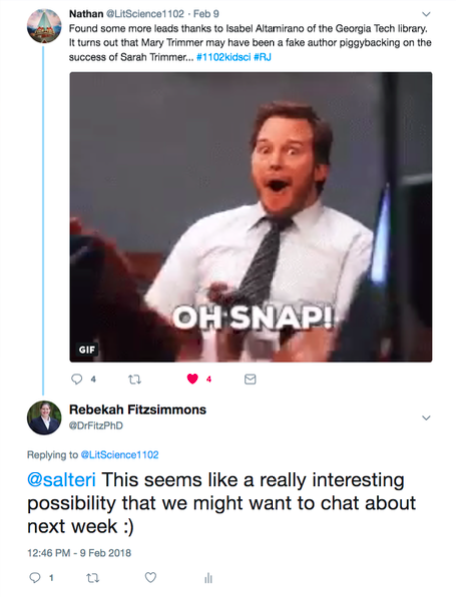

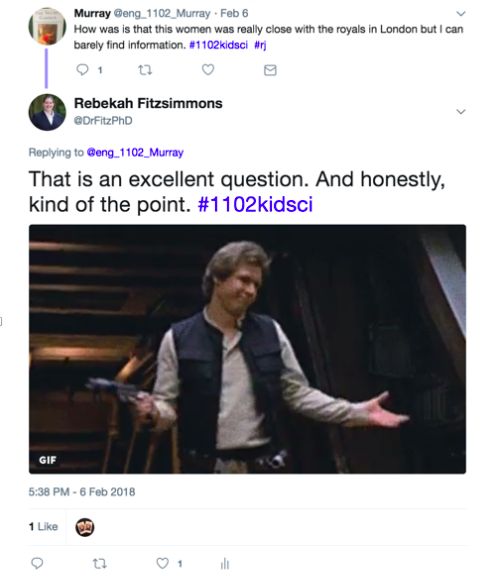

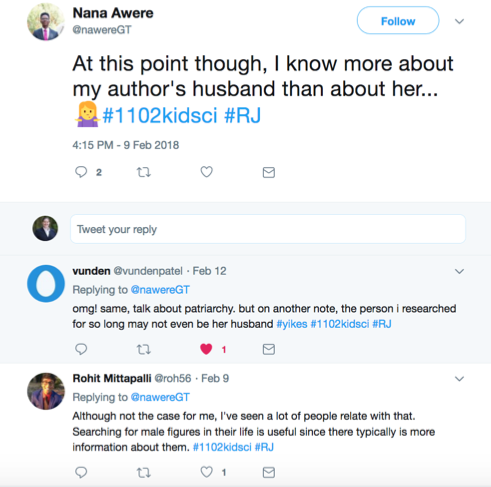

At a technical institute that only began accepting female students into regular classes in 1952, this assignment offered an opportunity to have students encounter firsthand the ways in which science relegated these women to the sidelines. By asking twenty-first-century students to research nineteenth-century female authors, the feminist lens of this assignment pushed students to ask (often in outbursts of frustration, such as the Tweets pictured below) why these women’s lives weren’t better documented. This project, aided by classroom discussions, directly confronted the myths that the lack of women in STEM fields is due to disinterest or biological/psychological dispositions of different genders, or that women have only begun to be involved in STEM in the last 50 years.

Figure 1. #RJ tweet exchange between the instructor and student Cheyenne Murray, who voices frustration about the lack of information about an author with significant political connections. (see original tweet: https://twitter.com/eng_1102_Murray/status/961018874882912257)

Figure 2. #RJ tweet exchange between three students noting the ease of locating information on male relatives compared to the female authors. (https://twitter.com/nawereGT/status/962083179191590912)

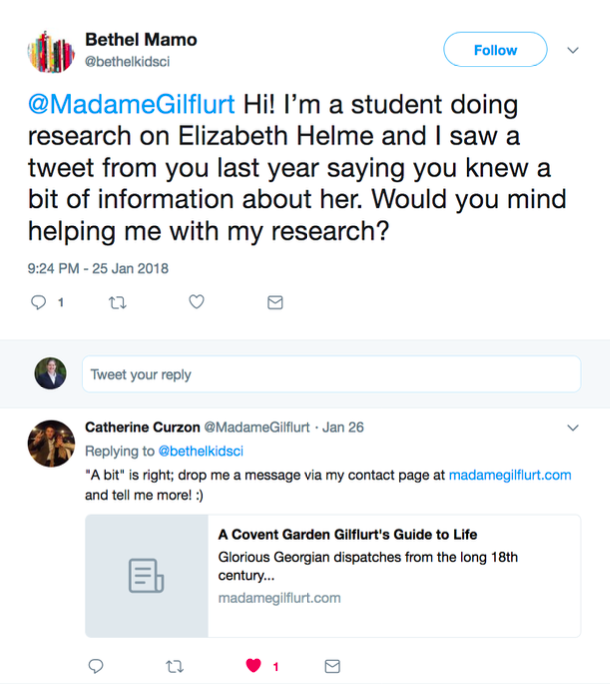

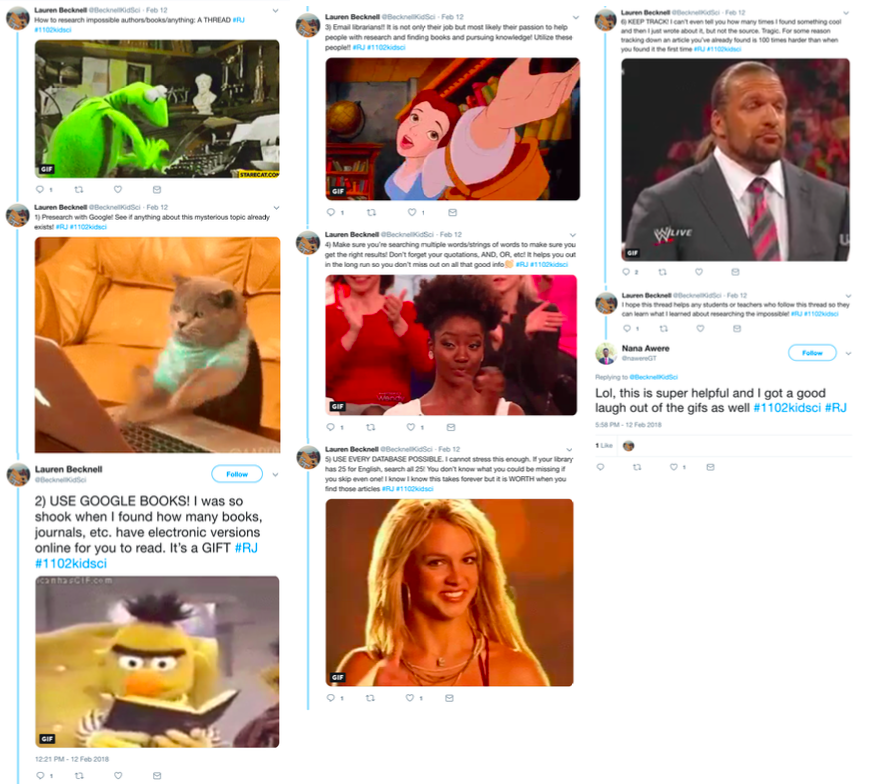

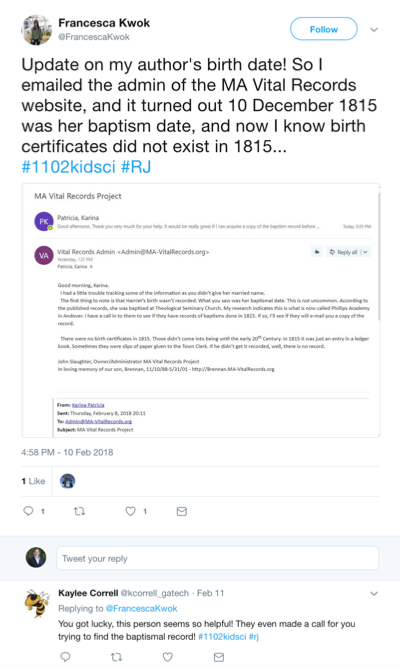

The second goal was to help students move beyond Google and to harness digital research technologies, including social media, to find information. To encourage collaboration and professional networking, students were assigned two required and one optional digital scaffolding components. First, students kept a real-time research journal via Twitter (see next section), where they regularly reported the steps in their research process over the course of one month. Second, each student wrote a WordPress blog post summarizing their work approximately halfway through the project and then responded to two other posts with constructive feedback. These posts were included on the course blog, a public-facing website, with all student names anonymized. Third, one of the final portfolio options allowed students to include an archive of their email communications with experts from outside the class. This last optional component was rather broadly sketched in the assignment, but students were given an in-class tutorial on how to compose a polite, professional email asking librarians, curators, publishers, archivists, or other scholars for information or research assistance.[7]

Figure 3. #RJ Tweet noting a significant discovery derived from an email exchange with MA Vital Records. (https://twitter.com/FrancescaKwok/status/962460819660398594)

Figure 4. #RJ Tweet exchange where one student points fellow students to a useful source about American authors. (https://twitter.com/gtac334/status/960404528876212224)

The third goal was to displace the expectation that the professor already knew all the answers and it was the students’ job to rediscover the “right” answers. Instead, the professor was presented as a partner in the learning process. This assignment contradicted the “banking” model of education in which “the teacher knows everything and the students know nothing” and “the teacher talks and the students listen—meekly,” (Freire 1970, 23). Using the problem-solving techniques of the inquiry approach allowed Fitzsimmons and Alteri to “introduce students to IL [information literacy] as a way of thinking that focuses on modes of thought involved in seeking appropriate sources” (Mazella and Grob 2011, 468).

At first, the unknowable nature of the assignment and the inability of the professor to accurately predict the successful completion of the ideal outcome—especially given the time constraints of the project, lack of access to physical materials, and the age of the material—made many of the students extremely uncomfortable. Many asked variations of the question, “But really, which of these authors will be easiest to research?” to which Fitzsimmons repeatedly replied “I honestly don’t know.” To many students, this felt like a drastic shift in the way they thought about research. Ben Ventimiglia[8] wrote in his final reflective portfolio essay[9]: “In high school, doing a research project meant googling the topic, reading the Wikipedia article, and maybe copying a few websites into a bibliography. Yet this project, as with everything else in this class, was different. This time, I wasn’t researching something that the teacher already knew about, this time I was researching something that hardly anyone knew about.” Some students even indicated in their blog posts that they initially assumed that Fitzsimmons and Alteri were only pretending ignorance. Kaylee Correll wrote in her blog post: “When first receiving the assignment for ‘The Possibly Impossible Research Project,’ I thought, surely Dr. Fitz has researched these authors and knows information exists on them. It’s just hard to find, so she’s challenging us to develop our research skills. Well, that has clearly proved not to be the case.” This was, in part, the very assumption the assignment was designed to challenge. In undermining the idea that the professor knows everything, this assignment offered students the opportunity to make meaning through engagement with an existing problem (a lack of information about a subset of scientific authors) and empowered students to become what Freire (1970, 27) terms “critical co-investigators in dialogue with the teacher.” In fact, most readily embraced the challenge of rediscovering knowledge and adding that information back into the historical record via the existing “Guiding Science” scholarly project and through public-facing Wikipedia articles.

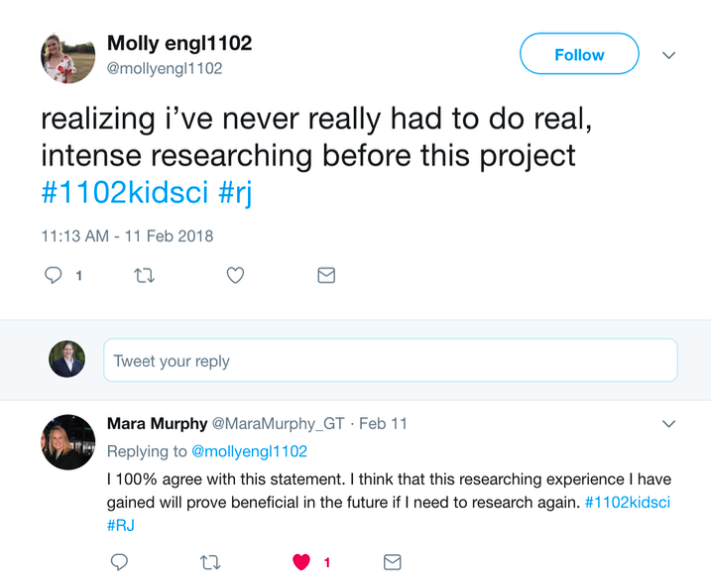

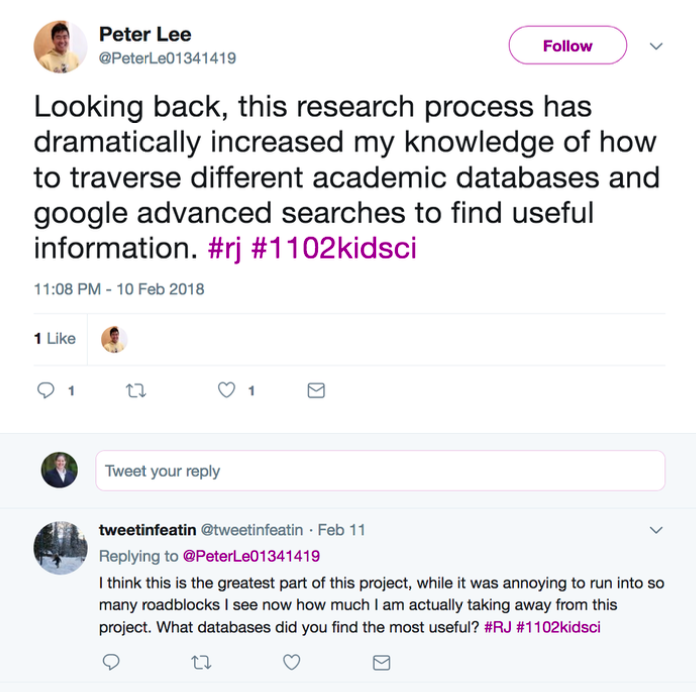

This project further emphasized the concept of research and discovery as a process. Both Fitzsimmons and the Georgia Tech research librarians who instructed the class on digital research methodologies and available library resources reiterated that the research that students would likely be engaged in as civil engineers, computer-science developers, and architects would reflect this same kind of open-ended problem solving. These students are likely to find themselves in industries where they are asked to create a solution to a problem that has no preconceived “correct” answer. The exposure to this kind of problem, paired with the opportunity to conduct original research in a first-year composition class where the stakes were relatively low, allowed students to embrace the challenge and reorient themselves toward a new way of thinking about research and their own educations.

Figure 5. #RJ tweet exchange where students discuss their previous lack of experience with “real research.” (https://twitter.com/mollyengl1102/status/962736430614306817)

Figure 6. #RJ Tweet exchange where students reflect on what this research process taught them and how it might be useful in the future. (https://twitter.com/PeterLe01341419/status/962553797032726529)

The fourth goal was intimately tied to the third: in asking first year students to engage in difficult, original research without the promise of results, the assignment actively set up many of these high-performing students to fail in order to teach them to cope with and work around setbacks. Today’s college-aged students, in general, enter college facing pressures and expectations from all sides, leading to a rise in stress, mental health concerns, and reluctance to admit to confusion or mistakes. Geoffrey Cantor (2017) notes that these pressures can come from all sides such as “the ever-increasing emphasis on academic success in our target-driven culture” as well as stresses “about their finances and the substantial loans that they have to shoulder” in order to earn the degrees they have been told are necessary to succeed in a twenty-first century economy. Cantor further notes, “Schools, particularly prestigious private schools, often project a highly competitive ethos, causing some students to drop out of the race, while others enter it with an obsessive determination to succeed” while familial pressures can turn a bad grade on a test into familial disappointment. The pressures can be high whether the student comes from a long line of legacy degree earners or a family with no higher education background.

Given the highly structured, outcome-based educational policies that govern most of today’s students’ K-12 learning experiences, college courses that offer a lack of structure, supervision, or clear expectations often make students intensely uncomfortable. As many college faculty can attest, students who face frustration or difficulty in completing a project may shut down, give up, or blame the instructor for a lack of clarity in directions or expectations. In response, colleges and universities are increasingly trying to find ways to work with the “failure-deprived” or high-achieving students who are “[n]early perfect on paper, with résumés packed full of extracurricular activities” but as a result “they seemed increasingly unable to cope with basic setbacks that come with college life” such as scoring a B on a test or missing a deadline on a paper (Bennett 2017). In using a digital pedagogy framework that embraces play, experimentation, and failure, this course sought to join other beneficial experiences aimed at helping students learn to cope with failure, while also helping demystify and destigmatize failure through collaborative work practices. Others, such as David Gooblar (2018), have noted that sharing failure can help to normalize it as well as provide students with coping strategies, both in and out of the classroom.

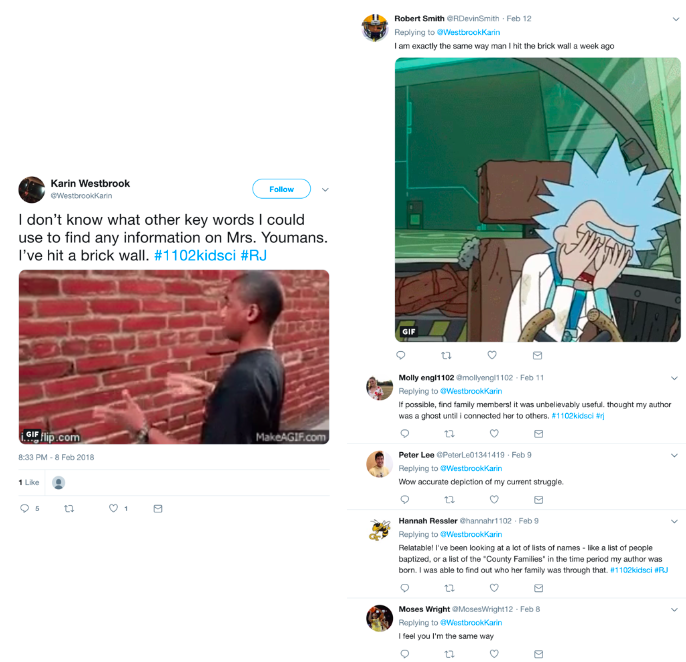

Figure 7. #RJ Tweet exchange between six students, commiserating on the frustrations of hitting “brick walls.” Some offer advice, others sympathy, solidarity, or encouragement. (https://twitter.com/WestbrookKarin/status/961790136190160898)

In this vein, the structure of the assignment was built around the risk of failure as a regular part of original research, thereby emphasizing the need to develop good research habits, such as recording and documenting the steps of a research process, and on creative problem solving in the face of setbacks. To do this, Fitzsimmons first made clear that she expected each and every student to fail, or at least to encounter frustrations and setbacks, which the class came to refer to as “brick walls.” These brick walls might include leads that did not pan out, searches that ended in no results, or email queries sent with no responses.

After assigning the project, Fitzsimmons devoted at least five minutes each class period to a research check-in. Students were regularly asked to discuss what they had or had not found, what resources had been useful, and where had they gone astray. Early discussions were hesitant and limited, likely due to the fact that many students had not really started their projects yet. However, after the blog post (and the flurry of research and tweeting that took place the weekend prior), students became far more willing to admit to running into brick walls. Once the students were willing to share to these failures with their peers, a focus on creative problem solving emerged. As students began to share successes, their approaches often inspired others. For example, as some students began to hear back from archivists and librarians, more students were willing to reach out via email to outside experts. As students had reported success with specific digital resources available through our library’s subscription service, other students began to work with the librarians and databases to find archival records, images, census data, publication information or more. In asking students to confront these brick walls and frustrations, and then move on to new approaches, this project mimicked likely scenarios researchers face in both academia and industry.

One of the many threads of conversation the class repeatedly revisited during the project was how to manage frustration and failure from both a productivity standpoint and an emotional one. In some cases, this meant letting students vent their frustrations, while Fitzsimmons, and eventually other students, validated those emotions; phrases like “that does sound very frustrating” or “I hate it when that happens” acknowledged the students’ difficulties while also recognizing how common failure can be. Often times, identification and sharing of similar experiences was enough to help students. In certain cases of prolonged and ongoing “failure,” the class would sometimes suggest other search strategies, brainstorm new approaches, or offer to share physical resources. In a couple of dire cases, reassurance took the form of reiterating the requirements of the assignment and asking the “failing” student to account for what they had already accomplished and how the work they were producing (research notes, works cited, evidence of emails sent) were all that the assignment required for them to earn an A.

Twitter Research Journals (#RJ): Leveraging Social Media In Archival Research

In an attempt to emphasize the concept of research as a process, Fitzsimmons asked students to keep a public-facing research journal using Twitter. Over the course of the month-long project, students were required to send 30 original tweets about their research process that included the course hashtag (#1102kidsci) and the assignment hashtag (#RJ). The students were also required to reply to 10 of their peers’ #RJ tweets during this time. Students were encouraged to send tweets about their ideas, successes, failures, frustrations, questions, search terms, and correspondence in real time, as their research unfolded.

Given its informal nature, many faculty members, including Shannon Draucker (2018), observe that “Twitter offered my students a venue in which to share their more casual, impressionistic responses to our course texts and to communicate their immediate reactions and emerging insights with each other.” Further, the use of multimodal forms of communication (gifs, links, images) in the digital platform allowed students to share a wider variety of information with peers and the general public alike, regardless of Twitter’s 280 character limit. As a result, this form of a research journal recorded the ups and downs of the research process and made the usually invisible labor of research visible, tangible, and humanized.

Figure 8. #RJ tweet exchange between a student and GT librarian Karen Viars, celebrating the discovery of a photograph of the student’s assigned author. Note the informality and collegial nature of Karen’s response, keeping largely with the tone set by the students in this collaborative space. (https://twitter.com/MaximENGL1102/status/961375465511546881)

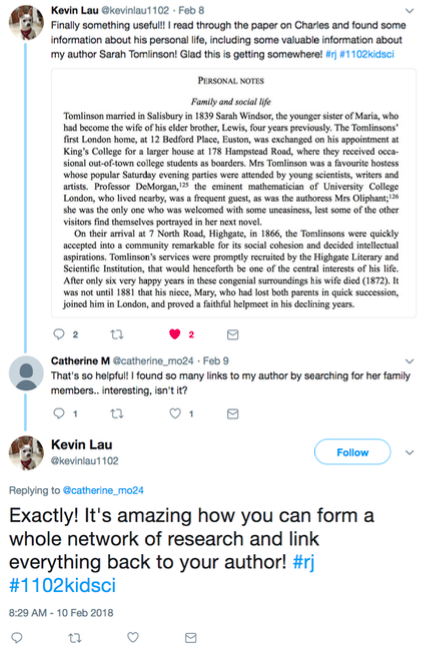

Figure 9. #RJ tweet exchange between Kevin Lau and a fellow student, featuring a photo of the original document in which Kevin found significant new information. (Tweet no longer available.)

The #RJ scaffolding component also allowed for real-time feedback and coaching from both the instructor and the Georgia Tech subject librarian, Karen Viars. In addition to Viars leading a workshop during class time on databases and digital resources, Twitter offered her the opportunity to respond to students and offer her expertise in an informal, collegial way. Given the nature of this project, both Fitzsimmons and Viars found it useful to reinforce a number of the concepts discussed in class, specifically the ideas that research is a process, that dead ends do not necessarily mean failure overall, and that finding no results in specific databases is still valuable information to be recorded and noted. Based on theories that experiential learning can provide more concrete learning outcomes, this real-time feedback in response to the students’ actual work likely made more of an impact than the in-class discussion of failure as an abstract concept. To encourage this tone and level of informality, both Fitzsimmons and Viars regularly responded with the same level of irreverence, humor, and emotion as the students.

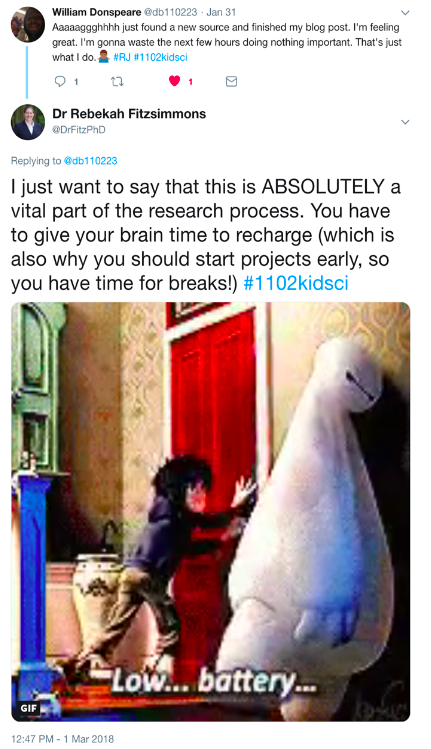

Figure 10. #RJ Tweet exchange that features an example of informal coaching from the instructor, using an animated gif to sympathize with the student’s frustration while encouraging the professional protocols discussed in class lessons. (https://twitter.com/DrFitzPhD/status/963225008154791939)

Figure 11. #RJ Tweet exchange between a student and the instructor that reiterates some of the process oriented lessons about research discussed in class, namely the importance of taking breaks and self-care. (https://twitter.com/db110223/status/958791263066775553)

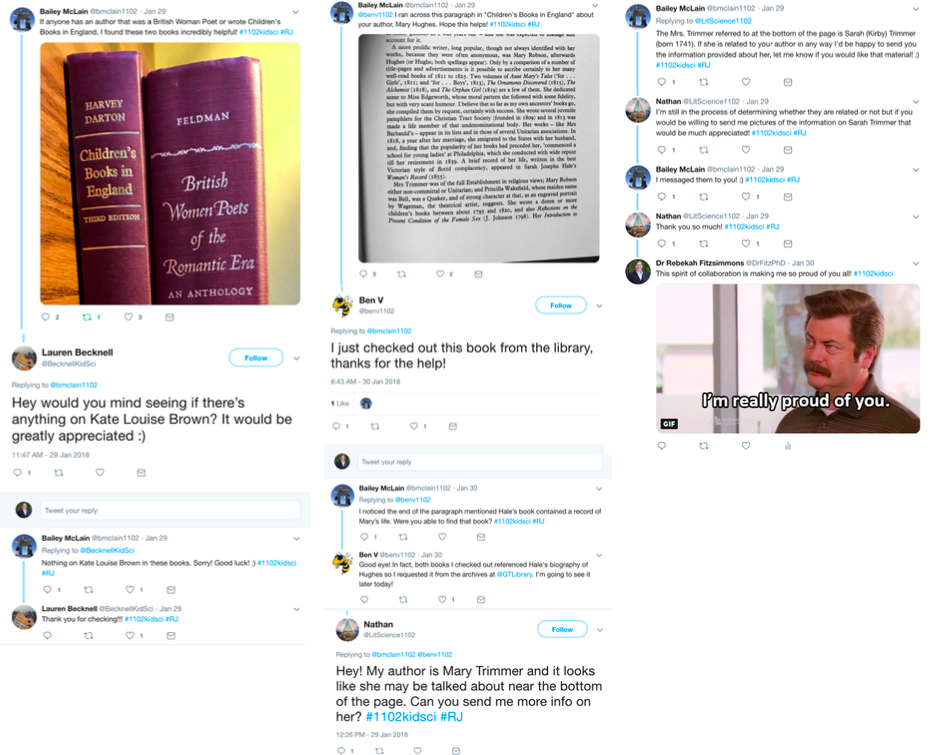

While one of the goals of the assignment was to teach students how to use social media to develop professional collaborative networks, the supportive and positive community that developed among the students within the #RJ hashtag discussions went far beyond the professor’s expectations. Although the assignment required students to reply to one another 10 times, most students quickly outpaced that requirement and embraced the digital space as a place to share database resources, books, articles, and search techniques. In her reflective portfolio, Annie Lee wrote: “Slowly but surely, Twitter became the place for collaboration. Between following accounts that may have been of help and exchanging ideas with my peers, we were able to create a community that was constructive and rewarding.” Many students admitted to turning to the Twitter hashtag when they felt stuck or frustrated, knowing that their class colleagues would have tips and new ideas for them to try.

Figure 12. In this extended #RJ Tweet exchange, Bailey McLain shares photos from a physical book she checked out of the library and offers to check the index for other students’ assigned author; she tags Ben Ventimiglia on a photo of that text that mentions the author he was researching. Another classmate from a different section read the text in the photo and replied to Bailey, asking for more information. Bailey messages him the additional information; the instructor responds at the end of the exchange commending the whole group for their generous collaborative spirit. (https://twitter.com/bmclain1102/status/957983681292980229)

The #RJ assignment also offered students an opportunity to leverage social media as a networking tool. In early class discussions, students were encouraged to seek out scholars and professionals on Twitter who studied relevant fields, like Victorian literature, children’s literature, or science communication. Over the course of the project, students used their #RJ tweets to track their conversations with the Georgia Tech library staff as well as their work in reaching out to other experts via email or social media. Many expressed surprise at how helpful and responsive the librarians were, rather than being bothered by their requests. Jae Hee Lee Lee noted: “In fact, the librarians presented to me resources I have never heard of before where I could find the rarest books (in this case, written by my author) and other sources verifying the reliability of the information I was finding.” Additionally, many students cited the class lesson on writing audience-centered professional emails (and sending thank you notes!) as one of the most beneficial parts of the project. In fact, a number expressed the idea that until this project, asking for help had felt like a last resort or an admission of failure. Perhaps because failure was an expected part of this project or because collaboration was actively built into the project requirements, many students described a new outlook on asking for help. In his final portfolio, Zong-Rui Wee wrote that this project

opened up a new side of research that I had never really explored—it is okay to reach out to authorities on a given subject to ask for help and to be pointed in the right direction. … I had struck a goldmine by reaching out to the museums and archives, and even when they had no physical resources for me, they had pointed me in the right direction. If reaching out to professors or archivists for information was not one of the few suggested options for the project, I would probably never have found as much information than I actually had.

Teaching students how to approach fellow scholars in a collaborative spirit as a valid form of research thus became a major unexpected outcome of the project’s focus on networking and social media.[10]

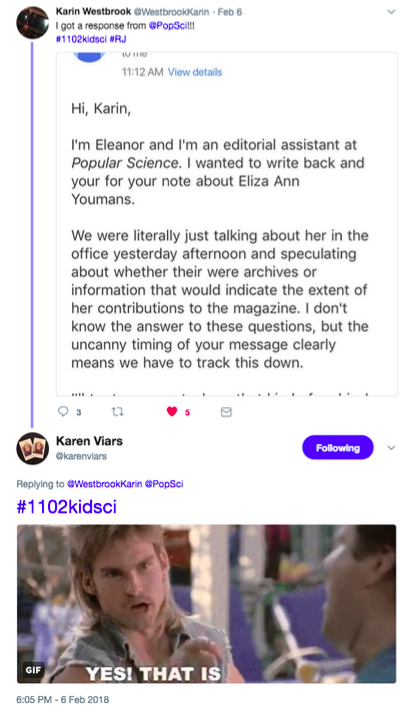

Figure 13. #RJ tweet by Karin Westbrook with a screenshot of an email from an editorial assistant at Popular Science; the magazine was started by the brother of the author Karin was researching. (https://twitter.com/WestbrookKarin/status/960911389656313856)