Background

Many of the new insights and much of the energy animating colonial studies comes from our archival research. Students are often eager to work with rare materials and to share unique aspects of their university’s collections with wider audiences, although even advanced undergraduates may not have the skills in early modern language, paleography, and archival protocols required for original research. In this essay, I explain the design and implementation of a seminar in which third- and fourth-year students in Spanish worked in teams to translate a handful of texts from Special Collections for the Early Americas Digital Archive (EADA), a free, open-access repository of texts published in or about the Americas from 1492 to 1898. In this way, students learn about colonial archives by approaching them as public-facing, meaning-making sites of translation, interpretation, and textual editing, and by remediating print materials from the archives into annotated translations.

Assignment Sequence

Beginning

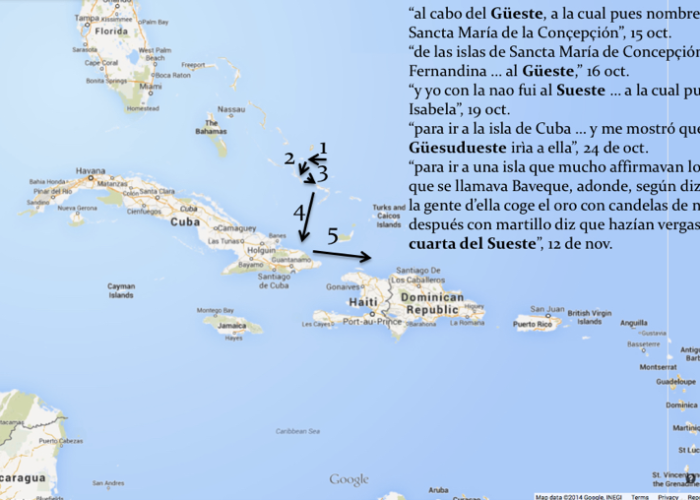

We begin the semester by asking students to analyze passages related to translators, interpreters, and message-shaping go-betweens in texts from the early Americas. By plotting the movements of Admiral Cristóbal Colón ([1492–1503] 2011, 63-93) on Google Maps, students visualized the ways indigenous informants shaped the movements of Spanish imperial agents (Figure 1). In this way, I take a familiar practice (close reading of literary passages) and use it to destabilize concepts that students thought they knew: empire, power, language.

In weeks two to six, we practice translation with hands-on exercises from the primary texts. In a Tuesday/Thursday class, I ask students to translate a passage from Tuesday’s reading, such as Colón’s finding “beautifully deformed trees” ([1492–1503] 2011, 69) or Cabeza de Vaca’s report of same-sex marriage ([1542–1555] 2011, 173). We review their translations in class on Thursday, debating the advantages and disadvantages of “deformed,” “different,” and “diverse” as translations of “están tan disformes de los nuestros” and analyzing the connotations of “idolatry,” “devilishness,” and “sin” for “vi una diablura.” To trace lexical emergences and common usages, we consult databases like the Real Academia Española’s Corpus diacrónico del Español (CORDE, http://corpus.rae.es/cordenet.html) and Nuevo Tesoro Lexicográfico de la Lengua Español (NTLLE, http://ntlle.rae.es/ntlle/SrvltGUILoginNtlle). As students compare translations in their groups, they appreciate how team members approach the task of translation in different ways and how small lexical variations impact the tone and meaning. This is one of the most challenging aspects of collaborative translation: each translator writes in her or his own voice, yet the group must find a shared tone that respects the historical tenor of the source text. To complement these in-class workshops, I sometimes assign theories and methods of translation (Benjamin [1923] 1968, Spivak 1992).[1]

Along the way, in week three, we transition to a “metadata analysis” of those sources, meaning that students begin to analyze them within the context of digital publics and archives. First, students review a curated list of archival texts that they might consider translating, sorted by theme (language contact, science, religion), region (Central America, the Caribbean, South America), and author (Gonzalo Pizarro, Hernando de Soto, El Inca Garcilaso de la Vega). Then, they meet with archivists in Special Collections to learn about rare materials: how the library acquires its collection, determines which materials to purchase, and classifies colonial works that defy genres, such as multilingual broadsides and maps with artwork. Students also learn protocols required to handle rare materials. After seeing how tightly the university controls access to colonial records, most students are excited to make these materials accessible to readers. We define “access” in two ways. These documents must be freely available and contextualized for general audiences so that non-specialists can understand them.

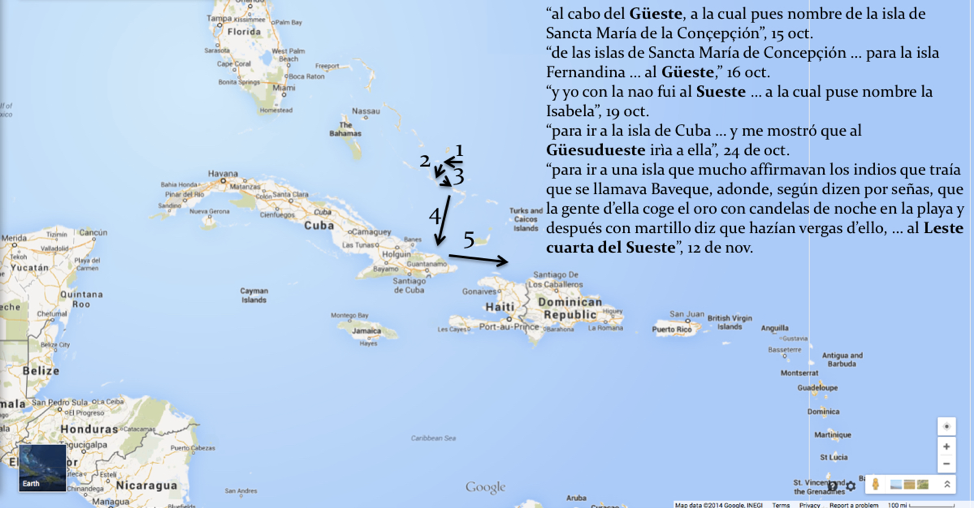

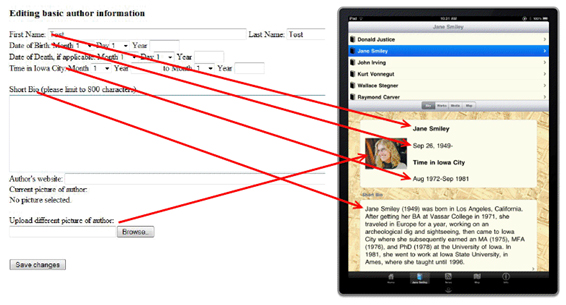

Independently, students work through a handout to evaluate the text’s content, interest to EADA users, and availability of other editions (Figure 2, distributed before visiting Special Collections). For example, Abby Kamensky, Mae Flato, Molly Hepner, Kayla Pomeranz, and Karla Núñez found a recent, scholarly translation of an important treatise on indigenous people of Mexico on Google Books (Palafox y Mendoza [1650] 2009). Because most of the text is not available in preview mode, they used an edition from Special Collections to transcribe and translate passages on law, foodways, and artisan practices (Palafox y Mendoza [1650] 1893). These themes complement other digital works, such as Sigüenza y Góngora ([1693] 1932) and Las Casas (1552), prepared by guest editor Rafael E. Tarrago from an edition held at the James Bell Ford Library of the University of Minnesota. The students thus understood their work as part of a larger process of archival formation with EADA collaborators at other libraries and universities, and electronic resources like Google Books.

The second part of the handout asks students to identify what they want to learn from the project. Some students seek practical experience in translation, while others want to make the work intelligible to non-specialists with well-researched footnotes. Students also specify which passages or chapters they will translate, explaining how they will balance this project and its challenges with their other coursework and commitments.

Middle

Students use the handout, which we work on in class, to write a formal proposal of one or two pages, which takes the place of a midterm exam (weeks six and seven). Each proposal explains how the selected text will enhance EADA readers’ understandings of early American history, literature, or culture, and how the student will design a manageable project within the constraints of the semester. For context, we review sample proposals of translation fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts. I removed all of the names and identifying information from the proposals and secured NEA approval before sharing materials in class. By evaluating recent, real-world proposals, students see how professional translators conceive of a project, justify its merit, and plan to bring projects to completion.

These proposals reveal how students understand archives and public-facing digital research. Some see digital archives as mode of preservation, as when Claire Gillespie chose to work with a manuscript that bears signs of water stains, deteriorating paper, and ink runs (Vendrell y Puig 1794). Others considered that the archive should fill gaps in public knowledge. When Hannah Berk discovered that no full-text digital edition existed of the order of King Carlos III (1767) to expel the Jesuits from Mexico, she resolved to make a bilingual edition that was freely available to readers. Emma Merrill identified a gap in the historiography, noting that a Dominican treatise about the excesses of women, fashion, and tobacco (Ramón 1635) was cited in important scholarly works from Latin America (Ortiz 1940), but not available in English.[2]

After commenting on and grading the proposals, in week seven, students are grouped based on overlapping interests like European empires in the Caribbean or Orientalisms in the Global South. These were the points around which two groups formed. Sutton White, Matt Trope, Anthony Correia, and Brent Nagel translated a Spanish diary of a British attack on Florida (Gálvez 1781(?)), and Taneen Maghsoudi, Kimia Nikseresht, and Tara Shafiei translated a Francophone account of Persia that connects orientalisms in the Middle East and Latin America. The latter group of students used their knowledge of Farsi to reveal these points of connection, recently studied by Camayd-Freixas (2013), and to correct Tavernier’s interpretations of medical practices, policies, and customs. So far, I have only grouped students by shared interests, although I can imagine pairing them based on complementary goals. For example, if one student wanted to build experience in translation, one wanted to research and edit, and a third wanted to manage the project, they could make an effective team.

Once students are in their teams, they transcribe the text to create a searchable record. This assignment serves two purposes: I have something tangible to grade before the final project, and students begin to develop collaborative methods. The interactive format of Google Docs makes it easier for teams to search and replace terms that they decide to re-translate, such as rendering “natural del pueblo” as “from the town of” rather than “native of” in Danielle Tassara’s translation of a Chinese labor contract in Cuba, or Ashleigh K. Ramos, Andreea Cleopatra Washburn, and Vanessa Macias’s decision to encode John Smith’s addresses to Queen Anne and Pocahontas in different registers to mark the gendered nature of both relationships in Álvarez(?) (1788).

End

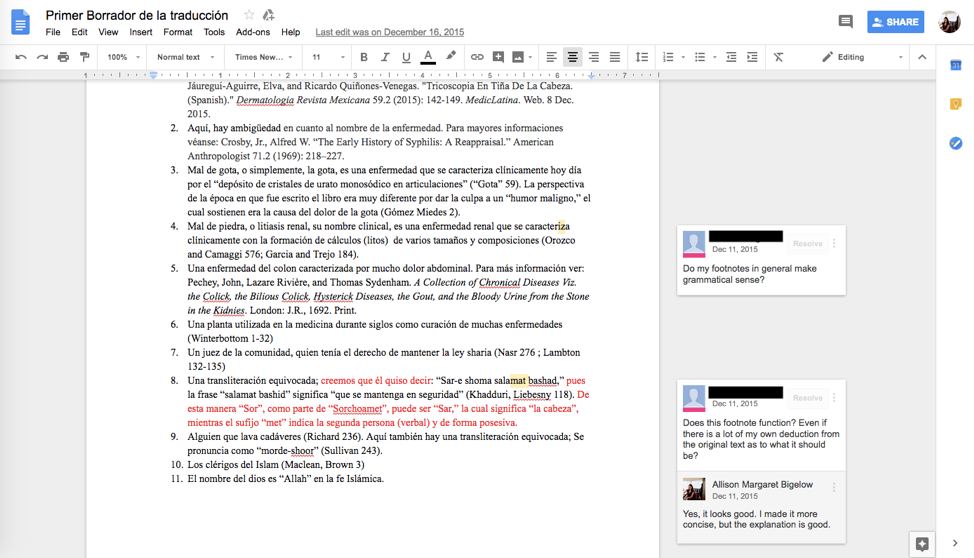

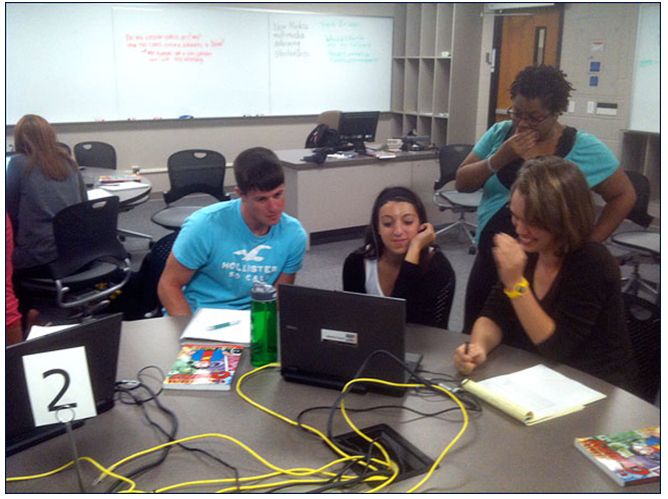

In the final month of the semester, we edit drafts during in-class workshops. I also meet with students in office hours and in Google Hangouts, often joining their drafts to edit and ask questions (Figure 3). One week before the due date, students submit complete drafts. I review them and add comments, either with pen and paper or on a Google Doc, depending on the group’s preference. By using low-tech collaborative platforms like Google Docs, students see that a task that sounds obscure—translating rare materials for a digital archive as a group—is actually within their reach.

On the day of the final exam, student groups sign up for a thirty minute appointment to review their work and submit it. One semester, I made the mistake of asking students to mark up their translations using XML, after learning it in a library workshop. None of the students were able to complete the markups. They ultimately submitted their work to the EADA site as plain text files, which editors at the archive finalized for publication. I realized that students were working hard to select, transcribe, translate, and annotate colonial-era texts, so I never repeated the XML assignment. Now, we send our work as plain text files to the managing editor, who reviews submissions for quality and consistency. This external review makes it easy to grade final projects: an undergraduate who writes for publication is doing excellent work. I grade the projects based on four parts: transcription, translation, footnotes, and letters of reflection in which students evaluate the contributions of all group members—including their own.

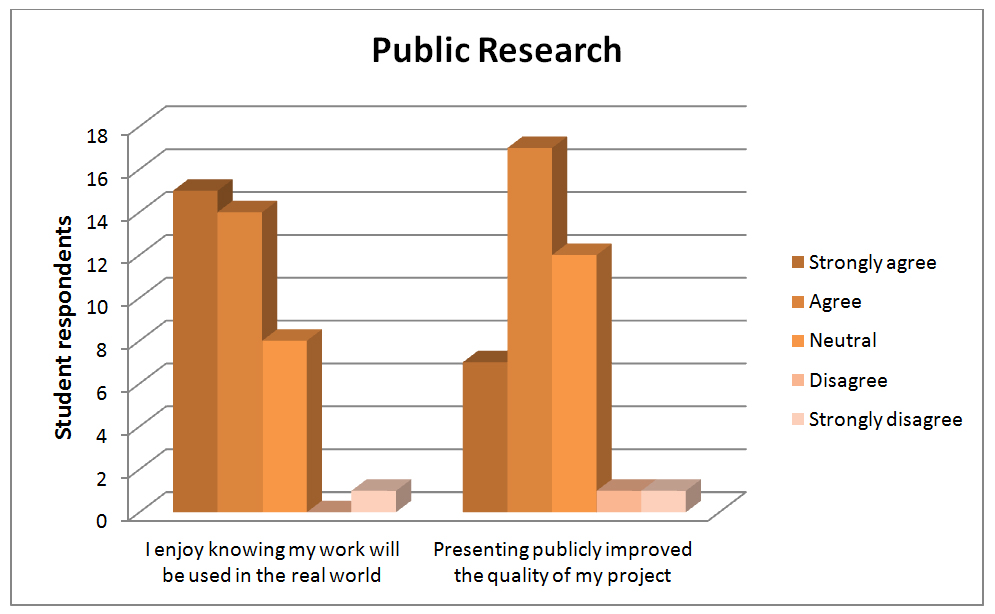

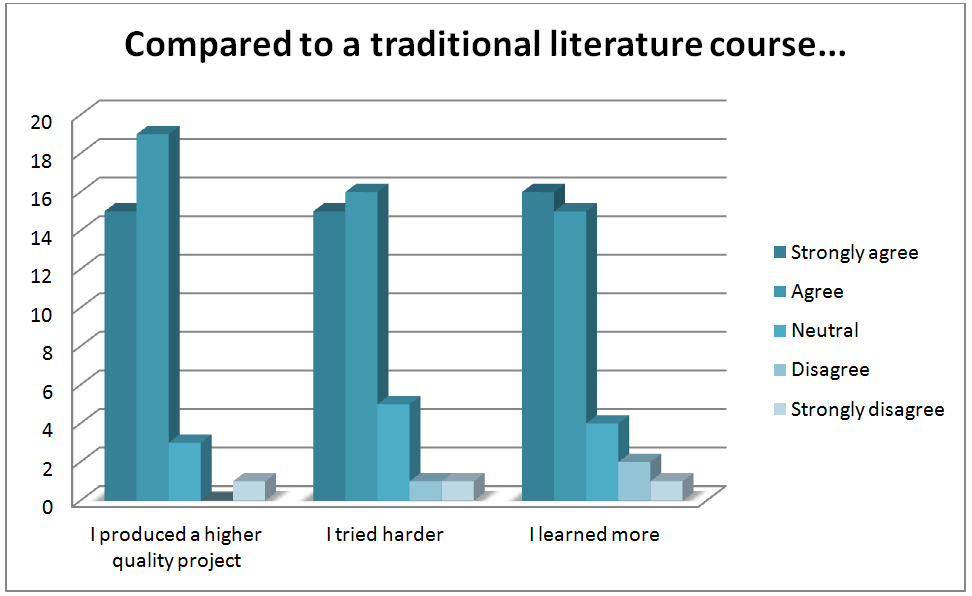

Student Response

Students generally enjoy the course, reporting favorably on meeting with professors, archivists, and librarians, and learning a variety of skills, including collaboration, textual analysis, and how “to help others in translating and teaching translative methods.” They also highlight the value of “meaningful work” in a “very fulfilling course,” writing, “I am amazed how much we accomplished in this course,” “The work was extremely practical…. Coming out of it with something substantial to put on my resume is great,” “the course gave me a sense of accomplishment that no other course had,” and “I could see myself translating texts in the future because of it.”

Teacher Evaluation

I have taught the class four times with twelve student projects, eleven of which are published on the EADA site. Because I work closely with students in each step of the process—selection, transcription (especially with manuscripts), translation, and research—teaching this course requires more time and energy than a course with a traditional research paper. It is also far more rewarding.

After teaching “Colonial Translations,” I began to incorporate projects with interactive technological components into my other courses, such as “Literatura indígena,” in which students wrote Spanish-language Wikipedia pages based on understudied aspects of indigenous history, literature, and culture (https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Usuario:Alisoneditorial). I also offer translation projects as options for students who want to combine academic and creative work, such as an edition of Sor Juana’s “Hombres necios” (Foolish men) in which Kate Eagen and Lisa Trinh, enrolled in a seminar on the Mexican nun, conserve the rhyme scheme and meter (http://eada.lib.umd.edu/text-entries/509/) in ways that the EADA edition of Sor Juana ([1689] 1920) had not.

By adapting a project-centered understanding of the archive, one grounded in projects that students develop, students understood in practical terms some of the theoretical questions—what is an archive, whose voices shape it, and how do we hear them?—that can be hard to teach. In the future, I will incorporate more theoretical and methodological readings on translation and digital publics to complement the practical orientation of the course.

Student Projects

Project: …. Francisco Álvarez (?). 2012. Noticias del establecimiento y población de las colonias inglesas en la América Septentrional: religión, orden de gobierno, leyes y costumbres de sus naturales y habitantes; calidades de su clima, terreno, frutos, plantas y animales; y estado de su industria, artes, comercio y navegación. Translated by Ashleigh K. Ramos, Andreea Cleopatra Washburn, and Vanessa Macias. Early Americas Digital Archive (EADA). http://eada.lib.umd.edu/text-entries/noticia-del-establecimiento-y-poblacion-de-las-colonias-inglesas-en-la-america-septentrional-religion-orden-de-gobierno-leyes-y-costumbres-de-sus-naturales-y-habitantes-calidades-de-su-clima-terr/.

Source document: Álvarez, Francisco (?). 1778. Noticias del establecimiento y población de las colonias inglesas en la América Septentrional. College of William & Mary (W&M) Swem Special Collections Research Center (SCRC) Rare Books #E188 .A47.

Project: “The Audiencia of Sta. Fee to the king, on the taking of Sto. Thome by the English in 1618.” 2014. Translated by Allison Bigelow, Mawusi Bridges, Shaun Casey, Julia Colopy, Eleanor Daugherty, Taylor Dorr, Mary Catherine Gibbs, Carly Gordon, Rebecca Graham, Alison Haulsee, Brynna Heflin, Kimberly Hursh, Lindsey Jones, Katherine Lara, Nathaniel Menninger, Sierra Prochna, Kyle Reitz, Blake Selph, Alexandra Soroka, Julia Sroba, Nora Zahn, Mary-Rolfe Zeller, and Emily Zhang. EADA. http://eada.lib.umd.edu/text-entries/the-audiencia-of-sta-fee-to-the-king-on-the-taking-of-sto-thome-by-the-english-in-1618/.

Source document: “The Audiencia of Sta. Fee to the king, on the taking of Sto. Thome by the English in 1618,” In Venezuela Papers, Vol. VIII, British Library Western Manuscripts Collection, Add MS 36321, 67-91.

Project: Benites y Gálvez, Bartolomé. 2014. Diario que hicieron los comisionados Alonso Hill Interprete de Indios, y Don Bartolome de Castro y Ferrer…. Translated by Patrick Johnson. EADA. http://eada.lib.umd.edu/author-entries/benites-y-galvez-bartolome/.

Source document: Benites y Gálvez, Bartolomé. 1790. Diario que hicieron los comisionados Alonso Hill Interprete de Indios, y Don Bartolome de Castro y Ferrer…. East Florida Papers Bundle 353. N. 17 170, April 6 (San Agustín).

Project: Gálvez, Don Bernardo de. 2015. Diario de las operaciones de la expedicion contra la plaza de Panzacola…. Havana (?). Translated by Sutton White, Matt Troppe, Anthony Correia, and Brent Nagel. EADA. http://eada.lib.umd.edu/text-entries/diario-de-las-operaciones-de-la-expedicion-contra-la-plaza-de-panzacola-concluida-por-las-armas-de-s-m-catolica-baxo-las-ordenes-del-mariscal-de-campo-don-bernardo-de-galvez_-havana-1781/.

Source document: Gálvez, Don Bernardo de. 1781 (?). Diario de las operaciones de la expedicion contra la plaza de Panzacola…. Havana (?) University of Virginia (UVA) Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library (SC) #A1781.G358.

Project: King of Spain (Carlos III). 2014. “Se extranen de todos sus Dominios de España….” Translated by Hannah Berk. EADA. http://eada.lib.umd.edu/text-entries/se-extranen-de-todos-sus-dominios-de-espana-e-indias-islas-philipinas-y-demas-adyacentes-a-los-religiosos-de-la-compania-assi-sacerdotes-como-coadjutores-o-legos-que-hayan-hecho-la-primero-pr/.

Source document: King of Spain (Carlos III). 1767. “Se extranen de todos sus Dominios de España….” México: s.n. W&M SCRC Rare Books Double Folio #F1231.M4.

Project: Lafitau, Joseph François. 2012. Histoire des découvertes et conquestes des Portugais dans le Nouveau Monde. Translated by Sarah Schuster. EADA. http://eada.lib.umd.edu/text-entries/histoire-des-decouvertes-et-conquestes-des-portugais-dans-le-nouveau-monde/.

Source document: Lafitau, Joseph François. 1733. Histoire des découvertes et conquestes des Portugais dans le Nouveau Monde. Vol. I, Book ii, pp. 123-125 and Vol. II, p. 485. Paris: Saugrain. W&M SCRC Rare Books #DP583.L16.

Project: Palafox y Mendoza, Juan. (1650) 2015. Virtudes del Indio, chapters V, VII, IX, XII, XIV, and XVI. Translated by Abby Kamensky, Mae Flato, Molly Hepner, Kayla Pomeranz, and Karla Núñez. EADA. http://eada.lib.umd.edu/author-entries/palafox-y-mendoza-juan/.

Source document: Palafox y Mendoza, Juan. (1650) 1893. Virtudes del Indio. Madrid: Tomás Minuesa de los Ríos, chapters V, VII, IX, XII, XIV, and XVI. UVA SC #A1891.C65 v.10.

Project: Queen of Spain (Isabela II). 2014. “Chinese Coolie Contract Regarding Work in Cuba.” Translated by Danielle Tassara. EADA. http://eada.lib.umd.edu/text-entries/chinese-coolie-contract-regarding-work-in-cuba-1858/.

Source document: Queen of Spain (Isabela II). 1858. “Chinese Coolie Contract Regarding Work in Cuba.” Collection of Spanish Language Manuscripts. W&M SCRC, Mss 1.16, Box 1, item 2012.146.

Project: Ramón, Tomás. 2012. Nueva prematica de reformacion contra los abusos de los afeytes, calçado, guedejas, guarda-infantes, lenguaje critico, moños. trajes: y excesso en el uso del tabaco… Translated by Emma Merrill. EADA. http://eada.lib.umd.edu/text-entries/nueva-prematica-de-reformacionnew-pragmatic-language-of-reformation/.

Source document: Ramón, Tomás. 1635. Nueva prematica de reformacion contra los abusos de los afeytes, calçado, guedejas, guarda-infantes, lenguaje critico, moños. trajes: y excesso en el uso del tabaco… Zaragoza: W&M SCRC Rare Books #GT509.R3 1635.

Project: Tavernier, Jean-Baptiste. 2015. “The Travels of Mr. Johannes Baptista Tavernier,” 335, 340-341, 343. Translated by Taneen Maghsoudi, Kimia Nikseresht, and Tara Shafiei. EADA. http://eada.lib.umd.edu/text-entries/voyages-through-persia-and-india-spanish-trans/.

Source document: Tavernier, Jean-Baptiste. (1686) 1705. “The Travels of Mr. Johannes Baptista Tavernier.” In Navigantium Atque Itinerantium Bibliotheca, edited by John Harris. London: Thomas Bennet, John Nicholson, and Daniel Midwinter, 301-348. UVA SC #G160.H27 1705, v. 2.

Project: Vendrell y Puig, don Miguel. 2014. “Mathematical Dissertation.” Translated by Claire Gillepsie. EADA. http://eada.lib.umd.edu/text-entries/mathematical-institutions/#colophon.

Source document: Vendrell y Puig, don Miguel. 1794. “Mathematical Dissertation.” Collection of Spanish Language Manuscripts. W&M SCRC, Mss. 1.16.