Kate B. Pok-Carabalona, the Graduate Center of the City University of New York

Abstract

This paper reflects on a semester-long experience of integrating several Web 2.0 technologies including Google Groups, Google Docs, and Google Sites into two Research Methods classes based on an active constructivist model of pedagogy. The technologies used in the course allow students the opportunity to actively engage with the central concepts in Research Methods under an apprenticeship model whereby they participate in all the steps of developing, conducting, and reporting on a research project. Students also interact with each other regularly through simultaneous collaborative writing and discussion. Despite evidence of the first and second digital divides as well as glitches and limitations associated with some new technologies, students overwhelmingly rated the experience positively, suggesting a promising argument for employing new technologies to make the central concepts in Research Methods more accessible and transparent to students.

Introduction

In the spring of 2011, I was assigned to teach two Introduction to Research Methods classes in the Sociology Department at Hunter College-CUNY. As I planned the course, I again faced the struggle of how to engage undergraduates in a topic that at times can seem fairly dry and abstract. Most students are accustomed to writing some kind of term research paper, usually requiring a visit to the library (or increasingly the Internet) to gather existing literature that they synthesize into new papers. But most of my students had never engaged in the kind of inquiry a research methods class addresses. Of course, term research papers as described above continue to be highly relevant and offer students practice analyzing, evaluating, and synthesizing literature. In short, such assignments strengthen students’ information literacy skills—an aptitude of particular importance in an age when the problem is more often too much rather than too little information. However, such assignments highlight only a small fraction of the skills emphasized in a research methods class where the focus is much more on practice—the framing, design, and implementation of actual research projects, the methodologies of conducting social science research.

I had taught Introduction to Research Methods several times before and each time I had learned better techniques to make the subject more relevant and “real” to undergraduate students. Lecture-only classes that depended primarily on textbook readings had morphed into classes that included substantial focus on analyzing the methods employed by researchers in existing journal articles. These classes had given way to ones that included more group work, more assignment scaffolding, and more technology to facilitate sharing student work and peer review. In short, I had steadily moved away from a top-down teaching style to one that was more experiential and constructivist, a style that seemed more fitting for the applied nature of research methods courses.

My previous attempts to integrate technology into a research methods course took the form of students using wikis to create ongoing “portfolios” of their semester-long work. Each portfolio could be reviewed by all students, making individual students’ research process, writing, and peer-review remarkably transparent. At the time, I worried that students might be nervous about making their work so publicly accessible to each other. Instead, many reported satisfaction that their work could be viewed by a larger audience. In fact, students seemed to find the process particularly informative and often incorporated each other’s comments as well as mine into revisions of their own work. They also seemed to take a certain pride in the idea that their work was being developed in a pseudo-published environment. In a perhaps controversial (but ultimately well-received) practice, students were able to see my comments not only on their own work but also on the work of their peers. Again, I worried that some students might be embarrassed by public critical comments, and indeed they expressed trepidation with this format. However, they later reported that they found this transparency refreshing; it seems that while the experience of being critiqued may be unpleasant, seeing just as many corrections on a peer’s work was liberating! Most students indicated that seeing the same error repeated by a peer helped them remember not to commit the same error in future assignments.

Despite these positive reviews, this format still clung to a top-down approach to teaching and learning. Moreover, students still seemed to struggle with the substantive content of a research methods course. Students gained a nebulous and indistinct understanding of the course, but full comprehension of core concepts such as designing and carrying out research projects remained just out of their reach. I hypothesized that part of the difficulty resulted from the stronger focus on procedure and practice in Research Methods compared to other sociology courses.

Introductory research methods courses may include considerations of theoretical paradigms, but at their core, they introduce students to how social science research projects are designed and carried out and how data is collected—concepts that are fundamentally process-oriented. While “hard science” courses such as biology or chemistry usually include lab components to help students understand the basic foundations of data collection in these fields, a similar practicum is often absent in social science research methods courses. This conspicuous absence is not a casual oversight on the part of social scientists; social science projects tend to be remarkably complex and unwieldy to implement. Unlike recording data in laboratory experiments or even collecting data on Drosophila flies to understand genetic mutation, sociological research projects rarely take place inside controlled environments and often require outside interaction with respondents (and usually quite a few of them). Moreover, many social science projects are fairly large undertakings, often carried out collaboratively by teams of researchers, and can take years to complete. As such, the experience of carrying out a social science research project can be difficult to replicate in only one semester. In the absence of research-based practicums, we ask students to read about how research is conducted and to imagine themselves into this process. Even assignments that ask students to write up proposals or draft surveys do not fully address how research projects are implemented or how data collection and analysis might take place. It’s these aspects of research methods that I felt students had such a hard time fully grasping.

Meanwhile, Web-based technology had changed rapidly even in the short time since I first implemented student portfolios, and I wondered if the nature of Web 2.0 architecture, with its emphasis on communication, scalability, web applications, and collaboration might offer some solutions. I was particularly interested in web applications, such as collaboration and survey platforms, that might allow me to implement an apprenticeship model of learning. This type of platform would allow students to actively learn about research methods by designing, implementing, and deploying a class-based research project. In fact, I had recently collaborated with researchers in a similar manner using Web 2.0 survey and publishing tools, so why not do the same with students on a class project? With these considerations in mind, I set out to integrate some Web 2.0 tools into my two Introduction to Research Methods classes.

Now that I have completed teaching these two classes (forthwith Class A and Class B), I can reflect on my semester-long experiment with integrating Web 2.0 technologies into Introduction to Research Methods courses. I should make clear that when classes began I had not planned to write a paper about the experience. Perhaps somewhat ironically then, this paper is not a methodologically planned, pre-crafted assessment of the effectiveness of technological innovations in teaching research methods. Rather, class outcomes and the seeds germinated by continuous student feedback and discussion throughout the semester resulted in my conlusion that this semester-long experience was worthy of a sustained post-mortem reflection on the steps, stumbles, and successes of integrating technology in research methods classes and pedagogy more generally.

Changing Pedagogy, Changing Technology

The literature on technology and pedagogy has grown steadily since the 1970s, but rose exponentially in the late 1990s as Web access became more pervasive. As late as the mid-1990s, only about 35 percent of American public schools were connected to the Internet; that percentage is now 100 percent (Greenhow, Robelia, and Hughes 2009). This explosive growth has been accompanied by a fast-paced rise in the construction of technology-based instructional classrooms and computer labs, a process that has steadily lowered student to computer ratios from 12:1 a decade ago to the current 3.8:1 (Greenhow et al. 2009). Penetration of Internet access outside of schools has been no less pervasive or fast-paced; Smith (2010) reports that as of May 2010, as many as two-thirds of American adults report having a broadband connection at home, up from 55% in May 2008.

Early Web architecture ushered in the transition to online library catalogues and facilitated access to academic information that might otherwise have been sheltered in imposing buildings, accessible only to elites or through cumbersome processes. However, it did not radically change the locus of the production or construction of knowledge. Information management on the Web continued to be restricted to “gatekeepers” who understood and had facility in its language (HTML) or who had the resources to hire programmers and designers to create their websites. The early Web, then, dovetailed well with forms of hierarchical knowledge construction, which remained largely the exclusive provenance of elites, specialists, or those with sufficient resources.

Given the relatively restrictive structure of this early Web architecture, it’s not surprising that academic interest and research into the nexus of technology and pedagogy also showed a marked weakness both in the integration of technological innovations by instructors and the ability to reinforce constructivist forms of classroom pedagogy. Studies of technological integration in classes at that time often reported that such attempts were fraught with the problem of simultaneously teaching course content with the more complex protocols of the technology, including HTML coding (Nicaise and Crane 1999). Attempts to integrate technology into classrooms often translated into a struggle between making the technology itself accessible to students and focusing on substantive course content. Predictably, these outcomes tempered academics’ attempts to integrate technology into classrooms, and arguably laid the groundwork for the continuing discourse over the limitations of technological innovation in classrooms.

While the Web 2.0 environment does not do away with these tensions altogether, it may lessen them, as Web 2.0 tools make it easier to contribute content to the Internet. Web 2.0 environments and architecture are characterized by a “read-write” model whereby users go beyond “surfing” the Internet to actually adding content through a multitude of venues and media, such as YouTube videos, comments, blogs, and Twitter. These environments have allowed the Internet to become an increasingly participatory medium, making it easier for users to become creators rather than just consumers of the Web by enabling them to add sophisticated content that is readily available for comment or revision. In these ways, Web 2.0 inherently embodies some of the main tenets of constructivist pedagogy, which similarly encourage students to be active participants in their learning through creation and discovery.

That being said, technology alone is not a cure-all for problems in the classroom, and the implementation of Web 2.0 technologies is unlikely to alleviate the “digital divide” (differential access to computers and the Internet) or the “second digital divide” (differences in technology use). These problems, which are rooted in socioeconomic disparities and are strongly correlated with race and sometimes even gender (Attewell 2000; Scott, Cole, and Engel 1992), may in fact be exacerbated by the use of Web 2.0 technologies in classrooms, by favoring those students who have had access to and experience with these new technologies. Moreover, the second digital divide is not a problem relegated only to students; there is evidence to suggest that wide disparities exist among instructors with respect to their knowledge and familiarity with newer technologies (Anderson 1976; Mumtaz 2000; Becker and Riel 2000; Wynn 2009). Finally, the ease with which information can be shared and re-shared comes with its own set of problems. As Jianwei Zhang (2009) cogently points out, Web 2.0 architecture may offer the promise of “generative social interactions, adaptability, interactivity, dynamic updating, [and] public accessibility,” but its unstructured and changing sociotechnical spaces can also challenge and even resist interpretation and synthesis— factors that limit the possibility of truly sustained knowledge creation.

Folk Pedagogy & Instructor Objectives

Before discussing the structure of the classes and how I employed technologies within them, it is important to clarify my own pedagogical preferences about the in-class use of technology since such orientations tend to be closely correlated with the ways in which technology is actually used (Gobbo and Girardi 2002). Like most instructors, one of my primary goals was to impart some greater understanding of the substantive content of the course. Here, my goal was primarily to help students develop a sophisticated understanding of research methods, as well as fluency in the working vocabulary and concepts of the course. Ideally, an illumination and demystification of the research process would allow students to develop the skills and knowledge necessary to evaluate existing research and conduct their own research projects. Because I had such end-goals in mind, my pedagogy does not fit strictly defined constructivist pedagogy whereby students locate and expand their own interests. However, neither do I fully embrace a top-down model of teaching and learning. Instead, I believe that students’’ active participation in process-oriented practice enables them to explore and truly build a sophisticated understanding of the central concepts in any course. Thus, my pedagogy is a constructivist one insofar as I view my role more as that of a facilitator and guide than as a disseminator of knowledge.

This pedagogical orientation has also informed my conception of technology itself and its incorporation in the classroom. As the Internet, smartphones, tablets, and e-readers have become virtually ubiquitous, it is increasingly difficult to live outside the realm of technological influence. Therefore, I believe that: 1) learning unfamiliar technologies better prepares students to adapt to future innovations; and 2) active engagement with technology may help to bring a wider group of students into the world of online knowledge communities. Going through the process of mastering an unfamiliar technology not only allows one to develop competency in its use, but also teaches students new ways of thinking and problem-solving that they can use in future encounters with unfamiliar tools. This is especially true for learning newer Web-based platforms, such as Google Docs, wikis, or blogs, which provide a different usage paradigm than desktop programs such as Microsoft Word, and are often public and therefore speak to a different orientation, intention, and purpose of creation. In contrast to closed content which is either private or limited to a few readers, the public nature of many blogs and wikis opens the creative paradigm to immediate public engagement, forcing blog and wiki creators to consider and reconsider for whom the content is created and for what purpose, and address the impact of discussions and issues of re-use. Moreover, the collaborative nature of wikis raises issues of individual authorship and ownership.

To provide scaffolding upon which students can develop such proficiency, I combine active participatory learning with the generative promise and possibilities of more constructive learning tools as afforded by these technologies. Students are not given entirely free rein to decide on projects and follow their own learning paths, because I have specific goals and objectives relating to research methods that I wish to impart to students. But I do apply some models of constructivist pedagogy by encouraging active student participation through conversation and feedback. My objectives for the class include the following:

- students should gain a better understanding of the substantive concepts of research methods;

- students should develop skills for critically analyzing existing research;

- students should gain a better understanding of planning, organizing, and conducting their own research project;

- students should gain an understanding of new technologies and apply the learning process to other unfamiliar forms of technological innovation;

- technology should be a pedagogical tool, not a primary objective;

- through understanding substantive concepts and the practice of knowledge creation, students should be able to think more critically and reflexively about the general concepts of sociology as well as communities of knowledge production;

- students should improve research writing skills.

In this way, I am attempting to harness some of the promise of Web 2.0 environments to enhance my students’ experience of the class and its content and to further my course goals.

Class Organization and Technology Components

The overarching structure for the research methods course was relatively straightforward: each class would select a semester project and collaboratively to design and implement a class project, culminating in a collaboratively written report. The classes did not collaborate with each other, but the students within each class collaborated with each other on significant assignments. In short, each class was structured along the lines of a collaborative community charged with the goal of choosing, developing, implementing, and reporting on a semester-long research project. In fact, I welcomed students on the first day by congratulating them on their new jobs as “Research Associates” for an as-yet-to-be-determined research project. Assignments, in-class group work, and homework were sequenced throughout the semester to assist students at each step. At first glance, this structure may not be altogether unusual in a research methods class, but present technological innovations made it possible to take these demands a step further— namely, each class was also charged with fully implementing most of this project online and collaboratively. Each class would work collaboratively to write and revise a research proposal, conduct a literature search, annotate and share a literature review, develop a survey, collect data, analyze the results, and write a final report. It is worth repeating that while a great deal of research was implemented online, much of the students’ work consisted of in-class activities including workshops in computer classrooms, small group and whole-class discussions, and short writing assignments.

The core tools used in the class were Google-based, including Google Groups, Sites, and Docs. All are freely available and allow users relatively good control over permissions and privacy; while initially it may seem like these constitute a significant number of technology tools, they are the minimum required to operate effectively in this environment. Google Groups served as our discussion forum and listserv and is the linchpin to all Google services, providing the means to easily share Google services with a large group. The threaded organization of Google Groups allowed students (and me) to regularly view discussions contextually, making conversations that took place outside the classroom far more robust. The main public class website as well as two private class websites were created using Google Sites. The private individual class websites offered a space where students could post their own pictures and profiles, and collaboratively create content. Together, these two tools were intended to foster a greater sense of community, connectivity, and dialogue. Finally, we used Google Docs as the primary writing platform to allow students to collaboratively create their bibliography, survey, and final report. A feature of Google Docs called Forms allowed students’ class surveys to be turned into online surveys to ease data collection and analysis.

In addition to these Google tools, I also incorporated a blog developed on WordPress.com. Although Google has its own blog platform in Blogger.com, I elected to use WordPress because I felt that it offered greater flexibility. Both classes shared the same blog and all students were added as authors to the blog (www.thinkingsociology.wordpress.com). I incorporated and created the blog in this manner for several reasons. First, I thought it could be used to address the more theoretical orientation of research methods courses by requiring that blog posts be analyses of students’ daily encounters with research methodologies and studies. In other words, I intended this blog to be an online version of students’ assessments of the research methods used in existing research. I thought such an innovation would encourage students to think through the types of research that get undertaken. I also wanted to reinforce the idea of more diverse knowledge communities. While their class projects could be seen as contributions to and extensions of a very academically structured literature, I wanted to show that such formal research projects were not the only avenues of knowledge construction. Finally, since an increasing number of students rely on the Internet for their research, I hoped that as they began contributing to this information ether, they would become more critical consumers of this material.

However, I quickly realized that this framing of blog posts made the blog rather difficult for students, especially early in the semester. This owed to the fact that this type of analysis is actually quite difficult to make unless one already has a fairly good understanding of the weaknesses and strengths of different research methodologies. Thus, the blog as I had structured it actually limited rather than clarified the central concepts of Research Methods.

Upon reflection, the disconnect between the blog component and the research project was clearly a creative failure on my part. I had not considered alternative ways of organizing the blog and my requirements for blog posts still made it a very outcome-oriented enterprise. If the blog had been more process oriented, it could have been much better intertwined with the class project. Moreover, I did not make the blog a required component of the class since I felt the course already made heavy demands on students. Instead, students were able to earn as much as three percent extra credit if they elected to participate by making posts or comments, but none were penalized for non-participation. I learned a valuable lesson in structure and pedagogy when students reported in their exit survey that they would have been happy to contribute to the blog had it been a requirement. In fact, when asked what suggestion they had to improve the class, this suggestion came up repeatedly.

Discussion: The Good, the Bad, the Ugly, and the Not So Ugly

In order to come to a better understanding of students’ perceptions of their technological skills, I began the semester with a survey created and deployed using the Forms feature in Google Docs. The survey comprised of questions moving from very broad to more exacting measures of technological skill and fluency. Questions included “On a scale of 1-5, how would you rate your technological skills?”, “On a scale of 1-5, how familiar are you with discussion listservs? Blogs? Google Docs?” etc. After students had completed the survey, I used Google Docs’ basic data summaries and charts to report results on each variable to both classes.

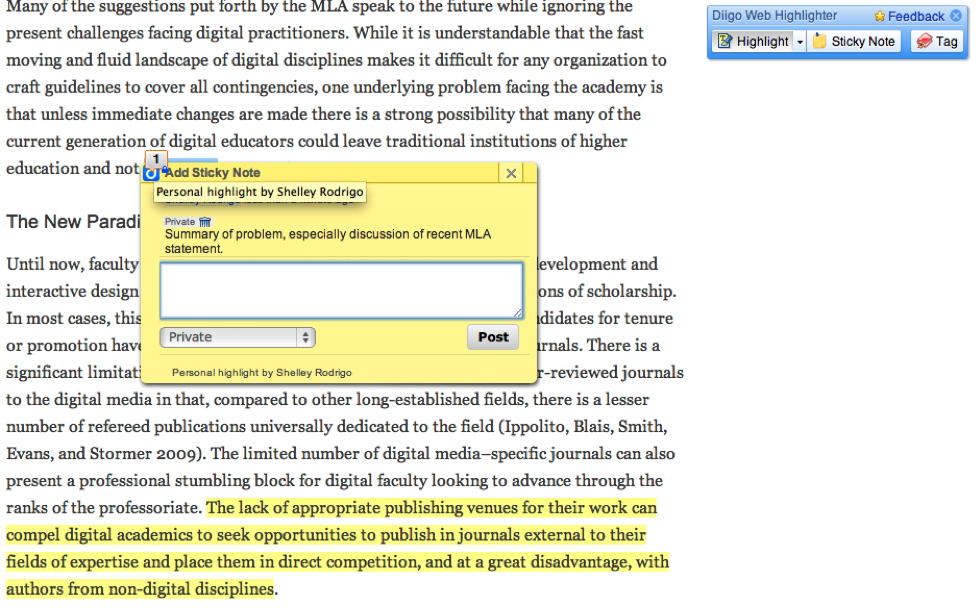

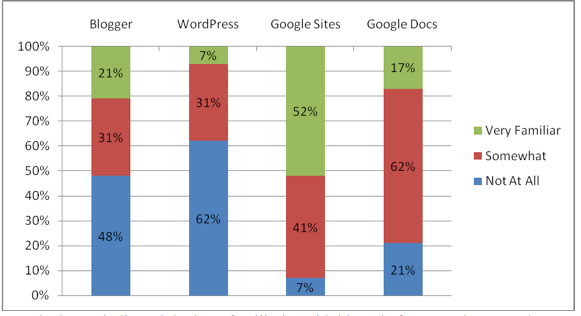

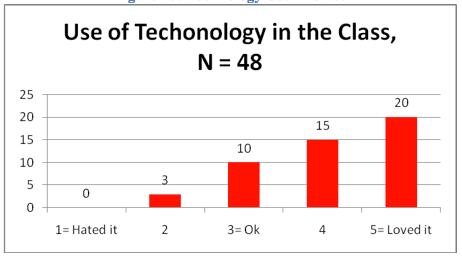

Not surprisingly, when technology was defined broadly, the large majority of students in both classes rated their own level of technology skills relatively highly (3-5 on a scale of 5). However, as these skills became increasingly defined by specific products, including discussion groups (Google Groups), Google Docs, Google Sites, wikis, and blog platforms such as WordPress or Blogger, students’ reported level of familiarity dropped precipitously (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Familiarity with Specific technology – Class A

Figure 2: Familiarity with Specific Technology – Class B

Both classes indicated the least familiarity with blog platforms such as WordPress and Blogger. It’s clear from these results that the largest percentage of students in both classes was either “Somewhat” or “Not At All” familiar with most of these technological tools. The outlier is Class B’s reported familiarity with Google Sites— a whopping 15 of 28 students (52 percent) of Class B reported that they were ‘Very Familiar’ with Google Sites. However, in subsequent class discussions, it became clear that my formulation of the question led to some confusion and few students in this class had used or knew very much about Google Sites. There were more mixed results for Google Docs. While as many as 15 of 31 (48 percent) of Class A and 18 of 28 (62 percent) of Class B indicated that they were ‘Somewhat’ familiar with Google Docs, this description turned out to be rather broad. Class discussions about these technologies revealed that few students actually made actual use of Google Docs. Instead, students reporting this level of familiarity also took it to mean that he/she remembered hearing about Google Docs or knew of its existence. In short, all the Web 2.0 tools planned for this course were relatively new to students in both classes.

This survey served several purposes. First, it gave me a rough gauge of students’ skills and perceptions of their own skills as they pertain to the technology tools I had chosen to use for the course. More importantly for the students, this survey offered them a first glimpse into one technological tool that they would soon be learning to use and also introduced them to a few of the central concepts in Research Methods—questionnaire design and the operationalization of variables. This exercise gave students their first chance to analyze and consider the importance of survey questions and how their construction affects and determines the actual data collected. Many students were startled to see the difference between how a broad and relatively unspecific term such as “technology skills” could yield radically different results once it was more rigorously defined, reinforcing the importance of clarity and detail in questionnaire construction. I hoped that that this experience would raise students’ curiosity and interest about research methods as well as the format of the course.

Once the necessary steps had been taken and the structure set up for collaborative work, students were ready to begin their new “jobs” as “research associates,” which included choosing a project, crafting a research proposal, developing a literature review, constructing a survey, gathering and analyzing data, and ultimately writing a final research paper. In short, students were ready to engage in all the activities that researchers undertake in genuine research projects.

Selecting a Topic and First Discussions

The students’ first assignment to select a research project immediately offered valuable insight into how Web 2.0 technology might be particularly useful. I initially assigned several in-class group discussions to encourage students to think through their nascent research proposals. I also encouraged them to use their discussion forum (Google Groups) to continue discussing their ideas. I was surprised by their dedication and readiness in adapting to an online discussion. Many of the online debates were as impassioned and sometimes as acrimonious as their in-class discussions. Moreover, ideas arising in online discussions were usually ported back to in-class discussions.

These discussions were also important because they made evident at least two problems that affected a relatively small number of students, but which I had not thoroughly considered. Those who were not accustomed to participating in online discussions found the extensive commenting somewhat disorienting. Many reported that since they receive email directly on their smartphones, they found the numerous posts a disruptive experience and were likely to just stop reading. The result was that these students might come to class unaware that several points or topics had already been discussed and debated by a large proportion of the students in the class. Consequently, students who did not participate were likely to feel as if their input was being ignored or disregarded while students who participated more readily in online discussions found it frustrating to have to repeat material that they felt had already been settled. I tried to rectify this issue by suggesting that students change their email notification settings in Google Groups to stop push notifications to their email and smartphones and participate in class discussion through the online portal. However, I also pointed out that their active participation in these online discussions was expected and a part of the course.

The second issue was more problematic and required more delicate handling. In some cases, differential participation in the online discussion resulted not only from a technological divide, but from a more old-fashioned delimiter between students: language ability and fluency. A small number of students for whom English was not a native language or who were uncomfortable with either their speaking or writing ability were much more likely to refrain from contributing to the discussion forum. Although I had sequenced an in-class discussion to prepare them for the online discussion, I had not required that they prepare anything written, believing that a pre-written statement would lead to less organic conversations online. However, I instituted a low-stakes writing policy whereby students were given time to write down their ideas to better prepare more reticent students so that they would at least have a base upon which to build their online comments. Moreover, as the semester progressed, extensive in-class group work helped foster greater familiarity and camaraderie and I found all students became far less reticent about participating in either in-class or online discussions.

In order to assess the extent to which the technologies used in the course contributed to clarifying the processes of and concepts related to conducting a research project, I asked students to complete a non-anonymous exit survey focused on the course format. Since the exit survey was extra credit, not all students participated in it; of the 56 students, 48 took the exit survey and eight did not. The results from the exit survey confirm that students found the Google Group discussion board invaluable to their work in this class. As much as 90 percent of students (43 students out of the 48 who took the survey) reported that Google Groups was useful.

Student A: I find it useful yes. I found receiving all the e mails as rather annoying, but overall feel the listserv was very useful for contacting the professor and other students. i feel it is was very useful in regards to the the communal aspect of the class and research project. For the project to be successful, i feel it was important for us all to be on contact.

Student B: It made it easy to communicate with my fellow classmates. I found myself communicating more with classmates in this class than others.

Even students who viewed it negatively found it to be a useful tool for communication:

Student C: Too many emails and it was frustrating at times. Although it was an easy way to communicate with group members it was a bit annoying to recieve 10 eamils within 5 mins.

Despite these issues, I believe that this exercise teaches a crucial lesson in a research methods class; these debates offered students the chance to experience the kinds of discussions, compromises, and considerations that often influence the choice and realization of actual research projects. In short, students’ own debates often mirrored the same processes among practicing researchers. I was thoroughly impressed with the level of these discussions and student engagement in them. Even students who initially expressed discontent with the technology or who were shy about participating in online discussions were eager to offer their opinions and defend their positions during class discussions. Moreover, since the selection of a research project took place over the course of a couple of weeks, students soon found a system that worked for them and all students began to participate more regularly in online discussions. In fact, perhaps the toughest part of this assignment was forcing students to narrow their choices and “settle” on only one topic. In a telling moment, Class A initially selected a research project centered on technology use and access. They even collaboratively drafted a proposal for this project. But after a growing feeling of injustice over what they perceived to be a social stratification system within their own college, they actually elected to change their project completely including revising and resubmitting a new draft proposal. Admittedly, I was thrilled that they had the chance to experience how the perception of injustice could inform their choice of a research project. Class A ultimately decided on a project that compared Honors College students with non-Honors College students. This project assessed the differences between these two groups of students, and attempted to gauge the extent to which the general student body was aware of the specialized Honors College program. Class B, perhaps influenced by the heavy integration of technology into this class, chose a descriptive project on New Yorkers’ use of Internet-enabled devices. Students wanted to research the demographic profile of who uses these devices, how they use them, and if technologies such as emails and text messages had usurped traditional communication such as phone calls. Both of these projects were challenging and sophisticated undertakings that essentially asked new questions requiring data collection. I believe that the level of sophistication owes much to collaborative revisions and in-class and online discussions.

Collaborating on a Proposal

Having successfully chosen a research project, students were required to collaboratively edit and create a page, titled Research Proposal, in their private Google Sites class website. I assigned them to do it on their wiki site because I thought they would enjoy seeing their class website evolve to reflect their semester’s work as each stage of their project contributed to building their website. Moreover, since Google Sites is a wiki platform, I envisioned the slow evolution and incremental changes so typical of Wikipedia articles. Instead, this assignment offered me and the students our first lesson in the incongruity between our expectations and outcomes when it comes to technology. Rather than slow, incremental changes to the assignment page, students were more apt to wait until the evening before the assignment was due to add their revisions. The result was a sudden influx and bottleneck of students competing with each other to add and delete comments. Worse, wiki platforms are not designed for simultaneous editing. Although a page is “locked” when it is being edited in Google Sites, contributors also have the chance to “break” the lock, and students did so with abandon, often causing each other’s contributions to be entirely lost. Their fear that they would not have contributed to the assignment prior to its being due easily overrode any sense of loyalty to each other.

In the class meeting following this debacle, I reassured them this farce was entirely a failing on my part. I clearly had failed to take into account the problems that might ensue from a mismatch between how students tend to work and the chosen technology. The wide-scale edits that take place in Wikipedia are radically different in scale and form than those that take place in smaller wikis with instituted deadlines. After this fiasco, we moved permanently to Google Docs for all future collaborative work and retained their class website primarily as a space for them to add more personal content such as pictures and descriptions of themselves— a makeshift Facebook, if you will. I do not mean to suggest that wikis do not have a place as a pedagogical tool; I merely point out that Google Docs offered a better fit for the purposes and assignments of this class. And although we largely abandoned their wiki as the primary space for the writing, I believe that its continued use as a more personal space for students encouraged the kind of camaraderie that eventually developed among the students. Many commented on each other’s photos and personal pages. Eventually, we also embedded various completed assignments into their website to give them a greater sense of progression, which they appreciated.

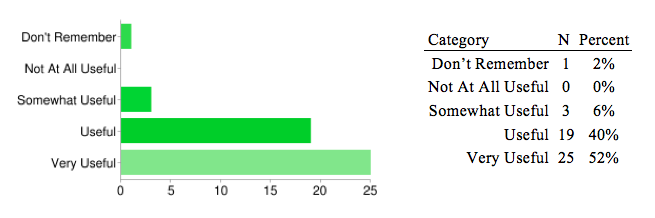

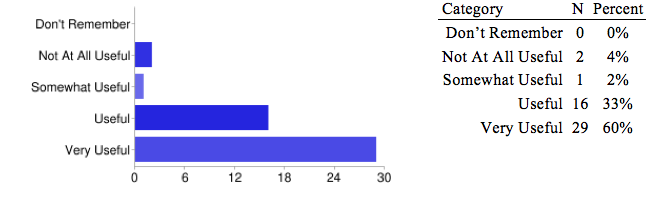

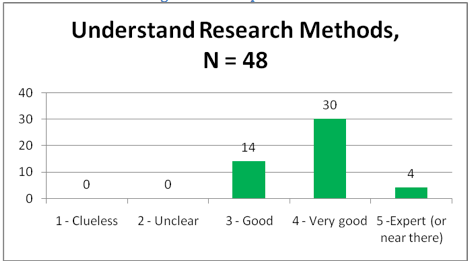

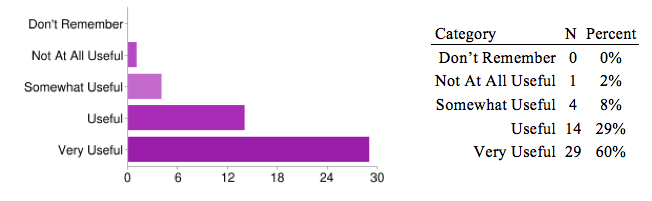

Understandably, this wiki assignment was particularly frustrating and students eyed the rest of the technological tools in the course somewhat warily. Given the problems in execution, I was surprised to see that students nevertheless rated this assignment quite highly in terms of usefulness as reported in the exit survey:

Figure 3: Usefulness of Research Proposal

I believe such high ratings reflect the importance of giving students the chance to discuss, revise, and make mistakes. Even if the assignment was far from perfect, it did demonstrate how committed students were to contributing to the assignment. Moreover, these repeated efforts to develop the assignment helped them to refine their ideas, ultimately resulting in a better proposal. It’s difficult to imagine a similar experience arising from a more traditional approach.

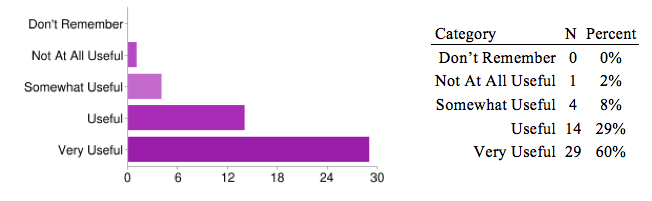

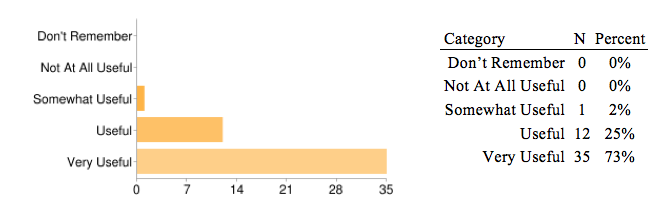

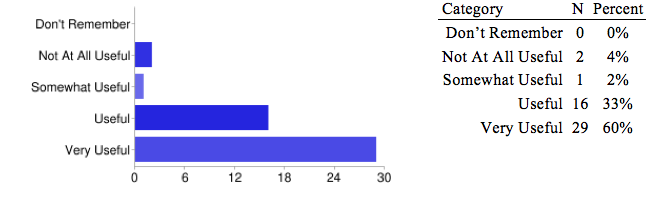

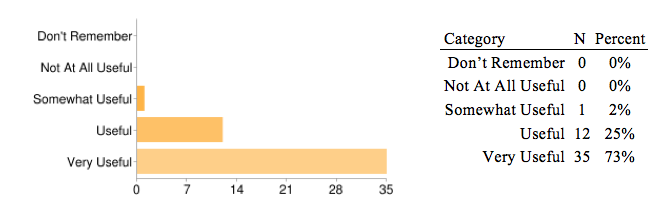

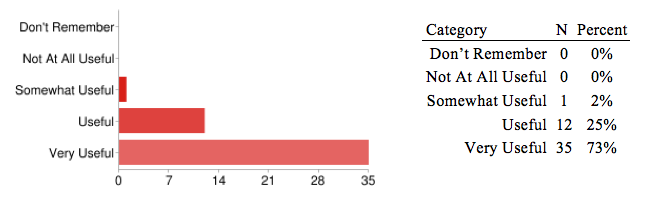

Sharing Knowledge through Collaborative References

The next assignment, a shared annotated bibliography, required each student to first locate ten journal articles that might be relevant to the class research project. In addition to sharing bibliographic references, each student also shared his or her search terms and strategies for locating articles. Thus, this exercise addressed individual skills-building as well as peer-teaching and development. Each student then annotated two articles and shared the annotations with his or her class. In this way, the students gained individual practice reading and assessing articles while participating in knowledge construction by creating a shared repository of knowledge. These assignments also received high ratings in the exit survey:

Figure 4: Usefulness of Shared References

Figure 5: Usefulness of Shared Annotated Bibliography

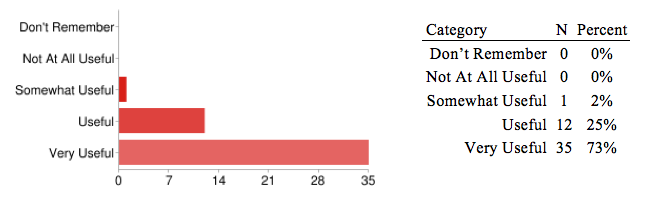

Constructing a Survey Together

Perhaps one of the most enriching assignments as well as the one that arguably took the most advantage of the benefits offered by Web 2.0 technologies was students’ collaboratively crafted project survey. After spending two to three weeks in small, in-class group activities developing broad themes (derived from their literature review) to include in their survey, students collaboratively created a questionnaire for the targeted population of their research project. The premise here was that through collaborative writing and ongoing discussions, students could develop a more rigorous and detailed survey than by working alone. By having students work in Google Docs, I could also view, monitor, and comment on their work in an ongoing manner; I could see not only how students’ ideas progressed, but also what concepts they struggled with the most. In short, I could provide continuous feedback to students as they developed their assignment. And while I never outright suggested survey questions, I did often highlight or prod them to clarify some of their own questions.

Figure 6: Usefulness of Survey Design

It was impressive to witness how often students commented on each other’s work and how often they made revisions based on other students’ comments. As students in each class struggled to create their collaborative survey, it was not unusual for individuals to make comments such as “Can we phrase this better?” “Let’s expand on this,” or “Shouldn’t we ask the exact age, rather than categories?” Even more impressive was how often my suggestions were ignored! This assignment also received very high ratings from students in terms of how well it contributed to clarifying concepts in Research Methods.

Of the 48 students who took the Exit Survey, only one indicated that this assignment was only “Somewhat Useful.” The rest of the students found this assignment at least “Useful” with a large majority reporting that it was ‘Very Useful.’ Of course such an assignment does not require using tools such as Google Docs, but students’ comments about using Google Docs contextualize the value of employing a Web 2.0 technology for such an assignment:

Student A: It was cool being able to see other classmates viewing/editing the document at the same time and have a real-time discussion about our document.

Student B: I started using Google Docs for my own personal uses after you introduced it to me in class. I thought the editing simultaneously part was the best!

Student C: Despite the times it froze and was inaccessible due to high volume of student usage, Google Docs was amazing because it allowed us to work [our] assignments simultaneous and provided the means of critical feedback and necessary editing.

Clearly, students felt that the simultaneous collaborative possibilities of Google Docs in combination with its integrated discussion component made the tool particularly useful for collaborative group work. The technology component made it possible for students to engage in an ongoing dialectic of discussion and creation, leading to the development of far richer and more detailed questions on their survey.

At this stage, in a more conventionally structured research methods course, copies of the survey might be printed and students assigned to go out and gather data. Such a process might entail gathering data, developing and readying the database structure to receive data, data entry, and learning the chosen data analysis software. Given the time-consuming nature of the process, this step is often skipped over. However, advances in online survey tools—particularly the ease with which they can be created and deployed—offer an ideal opportunity for students to attempt to answer their research questions by actually deploying the surveys they worked so hard to create. I initially planned for students to turn their survey document into an online questionnaire using Google Forms. I altered the assignment when I determined that while such a requirement would teach students how to use another tool, the skill itself would contribute little to clarifying the concepts of research methods. Instead, I used Google forms to turn their questionnaires into online surveys that they could then deploy to collect data. As a final quality check, students completed the surveys themselves before they were finalized. This exercise immediately made it clear to them which questions required additional revisions.

The next step included recruiting respondents and entering the data. At least two lessons learned during this process point to the importance of integrating survey technologies into research methods. The first lesson came in the form of problems students encountered during recruitment. At first, many students assumed that friends, family, and acquaintances would readily answer their calls for help to complete a class assignment. Instead, students reported that it was often difficult to get even these familiar associates to complete the survey. Students were forced to find methods for locating additional participants, thereby learning a valuable lesson about the complexities and difficulties involved in recruiting respondents. Again, I doubt that students would have had the same opportunity to learn such lessons without the chance to collect data as afforded by the integration of these survey tools.

A second telling moment came during the data analysis portion. Students could collect data in two ways: 1) conduct face-to-face interviews with respondents and enter the data themselves through the online link; or 2) send the link to the online survey directly to a respondent and allow for self-reporting. Although students elected the latter because it was seemingly more convenient, they quickly learned that the easy route was fraught with pitfalls. When at least one respondent participating in the survey entered “Klingon” as his/her race, they realized the cost of exchanging face-to-face interviews for the online survey and were immensely relieved that not all the participants had done the same. Once again, students learned a valuable lesson about the unintended difficulties of data collection that was able to be made more cogently because of affordances provided by the Web 2.0 tools used to perform and process data collection.

Ultimately, each class recruited nearly 300 respondents (8-10 respondents per student), and while the data collection process alone was irreplaceable, the fact that Google Docs also offered basic data summary tables and charts made this an even more valuable exercise for students. Students expressed pride and even awe in seeing their work summarized into colorful bar and pie charts. I wanted to show them how their data might answer their questions so we spent one class entirely devoted to statistical analysis. Students developed questions that they wanted to find from the data and I ran the analyses for them in SPSS. Again, they expressed pride in the types of answers they were able to determine from their data.

Even when students are provided with summary tables and sophisticated data analyses, turning them into coherent narratives still requires a certain amount of skill and training; it was here that students ran into the most trouble. While they could report the data summaries and even the results of crosstabs or inferential statistics that I provided for them, they found it more difficult to craft sophisticated answers to their research question using this data output. As previously noted, this outcome is not surprising given that the goals of an introductory research methods class do not usually include data analysis; most students go on to take an introductory statistics course which addresses this goal more directly. However, even without a clear understanding of the data analysis, students seemed to recognize that the process of data collection gave them a better understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of how data is collected as reflected in their high ratings of this exercise:

Figure 7: Usefulness of Data Collection

In fact, the Survey Design and Data Collection assignments received the highest approval ratings of all the assignments.

A Research Paper Beckons

This semester-long work culminated in a collaborative final paper written in Google Docs. Given the amount of work most students had already put into their project, I debated whether to assign a final paper; I ultimately elected to do so because I believed that it would address one of the concerns I had about relying too heavily on process as product. The strength of Web 2.0 architecture, according to Zhang, is the ease with which it is “generative [of] social interactions and sharing, adaptability, interactivity, dynamic updating, information, and public accessibility (quoted in Greenhow et al. 2009).” However, like Zhang (2009), I believe that these same strengths can too easily work against a sustained and steady evolution of ideas (Greenhow et al. 2009). In other words, the ease with which Web 2.0 architecture allows for sharing and commenting all too often leads to merely commenting or opinion-making, falling far short of the requirements of structured, formal education. For better or worse, the ability to write a coherent, cohesive paper is still at the forefront of standards of education— I know of no educational institution that rewards graduate students for merely speaking about their doctoral research. Discussion clearly helps to clarify concepts, but the ability to synthesize, interpret, and think critically about information (whether it arises from discussion, collaboration, or elsewhere) is equally important in academia and beyond. Nonetheless, I hoped that by making this assignment a collaborative one, such a goal-oriented assignment could also be combined with independent learning and constructivist models of knowledge creation.

The usefulness of this last assignment received slightly more mixed reviews. While a majority of students rated this assignment ‘Very Useful,’ at least a few rated it “Not At All Useful’ or only “Somewhat Useful.’

Figure 8 : Usefulness of Final Paper

This final assignment was the least popular of all the assignments amongand it easily garnered the greatest contention and loudest grumbles. Tellingly, student resistance was not necessarily to a final paper or report. Rather, student resistance centered on the assignment of a single and collaborative final paper. Despite an entire semester of collaboratively working together and often successfully producing complex and critical work, many students continued to worry about “freeloaders” and perceived disparities in writing ability and even critical thinking (I did offer students the option to write their own research paper if they preferred, but only two took me up on this offer).

A more general complaint about this assignment was directed at the technology itself. Although Google Docs claims that it allows simultaneous collaborative editing for up to fifty users at a time and can be shared with as many as 200 users, students repeatedly remarked on how slow the document could become when too many students were editing it at the same time, a factor that frustrated them and deterred their enthusiasm for the technology. It was clearly a difficult process to have thirty students all collaborating on one document even if it was only being edited by two to seven students at any given time.

Despite these laments, each class’s final paper represents some most of the most sophisticated undergraduate research work I’ve seen. I believe that what imperfections they exhibit result from the nature of diffuse, collaborative work rather than a lack of comprehension on the part of students. In fact, the ideas and concepts elaborated in each paper were relatively sound and creative. That being said, I tend to agree with their assessment— 30 students working on one single paper was difficult to manage. A few alternatives to this situation come to mind: 1) have students work in smaller groups of four to five students to write several papers; 2) have smaller groups of students simultaneously editing different sections of the same paper so that all students still have the opportunity to work on all parts of the paper; 3) assign different sections of the paper to smaller groups of students. Admittedly, the first and second options are the most appealing to me. In the first, all the papers would be on the same topic (the class project), but that does not preclude the submission of several papers and in fact such an approach is likely to allow for greater creativity and more nuanced details as each group may focus on different aspects of the topic. Meanwhile, the strength of the second allows for all students to work on all parts of the paper, ensuring that all students have similar levels of competency in all areas of the research project. By contrast, the third option is the least attractive and may still lead to some of the same issues involved with writing a single paper, and given the diverse voices, may actually result in a more discordant final report. Moreover, assigning different sections to small groups of students may limit students’ competency to their assigned section.

Grading such collaborative work was another challenge of this project, since it was such a central component of this course and also a primary concern for students. I tried to balance collaborative work with individual work by sequencing all larger assignments and offering individual credit for each smaller assignment. For example, students earned individual credit for participating in class discussions, locating and annotating references for the collaborative bibliography, creating survey questions for the class survey, collecting data, etc. While few students complained about this individual grading policy, the grading policy for the collaborative pieces was far more contentious since all students theoretically received the same grade on these components (the proposal, survey, and final report). My solution was to offer feedback at least two or three times as they were in the process of writing the assignment in hopes of improving their final work. Once the assignment had been turned in, I graded it. Then I used Google Docs’ revision history feature to track student contributions (see here). So long as students contributed to the work and made improvements to it, they received full credit (the grade that I had given the assignment). If students made only minor changes such as adding a period or indenting a paragraph, they received slightly lower grades. Students who made significantly more contributions than others received slightly higher grades. I also considered students’ comments, suggestions, and replies on the document as measures of participation, but with the stipulation that these could not be the only contribution to these assignments. I hoped that by making individual student assignments a relatively large percentage of their final grades, it would balance out any perceived injustice in grades on their collaborative assignments. Admittedly, this system was far from perfect–in particular, Google Docs’ revision history feature is not nearly as robust as I would like–and grading was a stressful task.

The literature on grading collaborative work suggests asking students to grade or rank contributions made by themselves and others. However, this suggestion would have been virtually impossible to implement given how I had structured some of these collaborative assignments. Since each class worked as a unit, how could thirty students grade or rank each other’s contributions? This struggle alone suggests revamping some of these collaborative assignments to be based on smaller groups and is something I’m seriously considering.

Final Remarks & Further Considerations

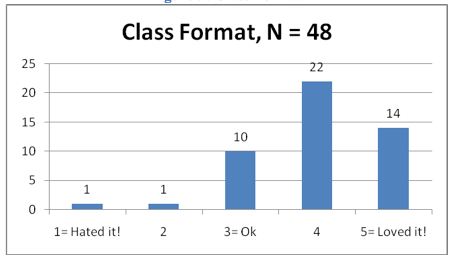

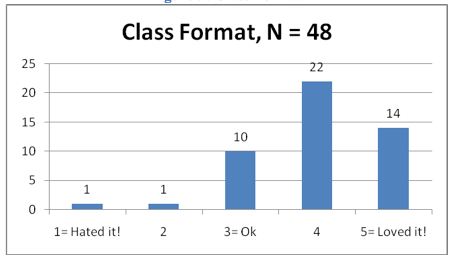

Figure 9: Class Format

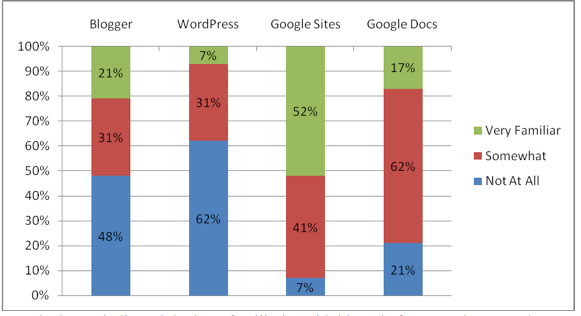

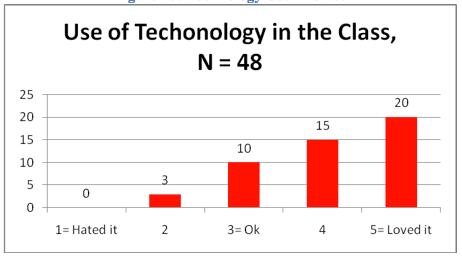

Figure 10: Technology Use in Class

In conclusion, the experience of integrating Web 2.0 technologies into these Introduction to Research Methods courses was overwhelmingly positive for both the students and myself. In the exit survey, students gave high scores to the class format and use of technology in the course. When asked to rank on a scale of scale of 1-5 where 1 was “Hated it” and 5 was “Loved it,” 36 of 48 students (75 percent) rated the format of the class a four or higher. Another ten students (21 percent) rated the course format a three, and only two students reported disliking the class format.

Students reported similar ratings for the integration of technology such as Google Groups, Google Docs, and Google Sites in the class with even more students giving the use of technology in the class the highest possible score of five.

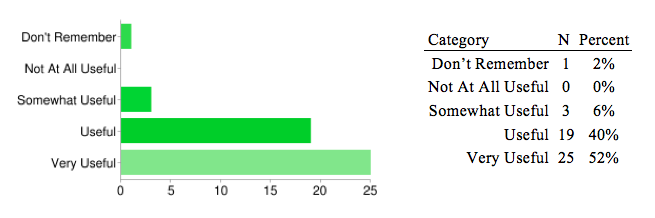

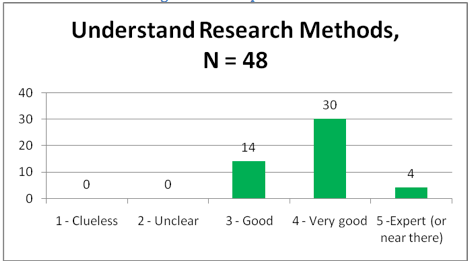

Figure 11: Comprehension

One final question in the survey asked students to rate their own understandings of research methods as a way to provide some kind of grounded base for reading these results. Although this was purely self-assessment, it is worthwhile to report that—at least by their own gauge—an overwhelming majority of the students reported that they now have a ‘Good’ to ‘Very Good’ understanding of research methods, and as many as four students think of themselves as experts.

Perhaps more valuable than how students felt about the course format, the use of technology in the course, or even their own understanding of research methods, were questions that specifically asked students to consider the extent to which they felt that the assignments and class activities helped to clarify the concepts and processes involved in conducting research. As Figures 3-8 (above) indicate, students’ responses to how well the assignments helped them to understand the central concepts of research methods was overwhelmingly positive. And while it is clear that a few students did indeed repeatedly report that they did not find these assignments useful, a much larger percentage of students regularly gave the assignments high marks in terms of their usefulness in clarifying concepts of the course. Moreover, the vast majority of students consistently gave the highest possible rating, “Very Useful,” to all of these assignments. Of course in the absence of other, more conventional assignments in this course, it is perhaps not too surprising that students would rate these assignments so highly. However, since each assignment was grounded in and designed to take full advantage of Web 2.0 technologies, I believe that a significant portion of their valuation can be attributed to this relationship.

In many ways, this format allowed students to gain a very nuanced, rich, and applied understanding about the central processes of conducting social research: survey design, implementation, and data collection. Together, these steps demystified the process of quantitative data collection and allowed students to directly address many of the most central issues and concepts in research methods, including ethics, respondent anonymity and confidentiality, cost, population sampling and design, and questionnaire design and construction. By structuring the class in this way, the course effectively became a problem-solving exercise—how would students structure and organize their inquiry to best answer the research question they had chosen? Such an exercise can easily be translated beyond the confines of a research methods course.

The incorporation of Web 2.0 technology tools allows research methods courses to be conducted in an apprenticeship model, giving students the opportunity to learn about research methods and methodologies by conducting research. Could such an apprenticeship model be conducted without the use of technologies such as Google Docs, Google Groups, and Google Sites? Yes and no. Certainly students could be asked to work in groups to collaboratively create a survey, but this method would result in several surveys that would have to be re-synthesized into a single survey, a process that would require significant time either inside or outside the classroom. Another option is for students to email documents back and forth to each other as researchers have traditionally done. However, part of the strength and richness of students’ surveys owed much to the fact that the entire class collaboratively contributed to a single document, creating, adding, or revising questions and expanding on concepts. Moreover, I continue to believe that the ease with which the survey could be deployed and data collected and summarized makes this a unique addition to research methods courses. In the absence of such tools, the data collection and analysis portions of this assignment would have required significant class time devoted to explaining the use of quantitative software such as SPSS.

However, far from being a panacea to smooth over differences between students, the integration of these digital tools and the format of the class also contributed their own set of problems. By far the most prominent problem was the persistence of both the first and second digital divides; students who had more access to computers at home and expressed greater comfort using newer technologies—those who were more likely to say that they followed blogs, had contributed to blogs, or saw themselves as particularly comfortable in online environments—were also more likely to be committed to the format of the class and to learning the technologies used in the class. Students who were more comfortable in a traditionally structured classroom found the class somewhat confusing and reported feeling uncomfortable navigating the numerous technological resources used in the class.

Student D: Google documents was useful, it let the class work together and we could see what each other was working on, so it helped. However, there were issues with working together on google documents that made it difficult to fully appreciate it.

Student E: I was a bit weary about google docs because I’ve never used them before. I got used to working with google docs towards the end of the class but I would say to have an extra class showing up more about how to use google docs.

Student F: It was better than blackboard but I’ll never love online work. It’s a bit confusing.

Student G: I learned alot about using Google document… it would be nice if you taught us how to use before we had to figure it out ourselves and it took me days to learn which i lost motivation …

For this group of students, rather than making it easier to collaborate, online tools made the process more intimidating and confusing, and they often expressed a preference for traditional group work where students meet outside the classroom in small groups to work on an assignment. Moreover, even for students comfortable with technological innovations, it was clear that the promise of these new technologies as described in much of the literature remained theoretical. Students often stumbled in working with these technologies, and many still required considerable guidance to critically assess and use these online tools. To address this issue from a pedagogical standpoint, it is crucial that instructors continuously monitor and provide sufficient training on all technological tools, as well as make sure that the use of these tools does not become the central part of any grading scheme. Additionally, steps should be taken to ensure that students have equality of access to hardware—if a student does not have home access to computers, laptop lending or other similar programs should certainly be considered.

Despite these concerns, the fact that so few students provided consistently negative feedback about either the course structure or content leads me to believe that the vast majority of students felt that the class structure contributed to their understanding of course content. Further, while the second digital divide was evident among students, exposing and training students on these technologies affords the opportunity to go through a process of learning that may help them learn unfamiliar tools in the future, thereby narrowing that divide.

It remains to be seen how applicable or useful Web 2.0 technology is to all courses. Generally, “real-world” research projects are collaborative enterprises, and a fair number of researchers have learned about research methods through experience and practice. Thus, the technologies integrated into this course fit particularly well with the demands and paradigms associated with research methods. However, that does not mean that these technologies are equally applicable or suited to all courses. My misstep with my initial implementation of the class blog demonstrates how important it is for instructors to think carefully about how they wish to structure the tools they plan to integrate. While my initial structuring of the class blog led to very little participation, after I opened up the discussion to any topic students could relate to larger sociological concepts, students immediately began adding content. Thus it was not the technology itself that was ineffectual, but how I had designed the assignment.

Their few posts immediately demonstrated that at least one strength of blog platforms lies in the opportunities they offer for students to critically reflect on broader issues and themes from other courses. It also hinted at an interesting pedagogical issue. Just as students sometimes ignored my comments on their collaborative work, preferring to pay attention to the comments of their peers, their few blog posts made quite plain the diffuse nature of information and knowledge construction. That many of the students made posts on topics that I was either unaware of or which were of no concern to me, but nevertheless seemed quite valuable to them, speaks to a more complete decoupling between instructor and the dissemination of information. The more such free-form tools are integrated into teaching, the more the nodes of knowledge become diffuse and multiple. Just as specific Web 2.0 technologies were used to fulfill a constructivist pedagogy in this Introduction to Research Methods course, the integration of a blog platform in more theoretical courses may better fit the demands of constructivist learning in them.

A more generalized problem with using these technologies is that despite their advances and functionality, they have not actually quite caught up with the demands and requirements of an academic environment, probably because they were not designed initially for academia. There is no unified digital platform linking knowledge creation, bibliographic management, and project management. Because Google Sites does not allow single pages to be locked, I juggled a main website alongside two class websites which were kept private and accessible only to students; this made the flow of information somewhat disjointed. In addition, because bibliographic and annotated reference management was somewhat makeshift and clumsy (we used the spreadsheet option in Google Docs for this purpose), their papers were written in Google Docs, and their blog was hosted entirely on a different online service (WordPress), students found the flow clumsy to navigate. In the words of one student, it was actually “information overkill.”

A final problem, more related the constructivist and somewhat self-directed format of the class than to technology, should be noted: some students respond better than others to different styles of teaching. A constructivist model demands a great deal of self-motivation and self-discipline on the part of students and it is paramount that instructors remember that in many ways, this requirement may actually be an added burden for both teacher and students. To my great surprise, quite a few students (although a relatively small minority) requested more and greater instructor oversight in the form of regular quizzes (to ensure that they read the assigned readings) and mandatory assignments (including the blog). While I worried that my presence on their discussion board or my ability to review their work in Google Docs was too intrusive or dictatorial, many students reported preferring that I provide even more feedback, especially in the form of PowerPoint presentations and even lecture notes to make sure they grasped the most important aspects of the course. In short, many students reported preferring a more top-down approach toward discipline and control. And although a relatively small number of students indicated such preferences, it does speak to different learning styles that some students may find the more free-form constructivist model of pedagogy more difficult. However, such demands may need to be balanced with the goal of fostering greater self-discipline in students.

What has emerged from this experience is that despite some problems, Web 2.0 technologies offer a promising and tantalizing possibility for making the concepts of research methods courses more accessible and transparent for many students. In addition to making it possible for students to carry out fairly complex projects, it helped to foster a sense of community among students and helped them to see themselves as active knowledge creators and contributors. Clearly, instructors must continue to be aware of the way students actually work to ensure a proper match between technological tools and assignments; since many students are likely to wait until the last minute to complete an assignment, this fact may well determine how to structure an assignment. And while we must continue to consider differential levels of technology use among students as well as cultural contexts (Bruce 2005), I firmly believe that the technological tools employed as described offer students the chance to engage with the central concepts of research methods in a manner that would not have been possible through a more conventionally structured course. Moreover, the collaborative nature of these tools bolstered student confidence, helping to foster a sense of ownership and pride in their own contributions to the overall project, which could be readily identified by students and myself; students often proudly pointed out which questions were “hers” or “his” at various times throughout the data collection and analysis phase of the project.

Additionally, the sense that educational institutions continue to play technological catch-up persists, as an overwhelming number of students preferred even these ad hoc digital methods of course organization over those of Blackboard. When asked if they would have preferred if we had worked more in Blackboard, only eight (17 percent) students answered “Yes” while forty (83 percent) reported “No.” Those who preferred Blackboard usually did so for the sake of convenience, noting that it would have been easier if this course could be found in the same place with their other courses, more than any other reason. Finally, it is clear from student comments that they found learning the technology itself a valuable experience. There is little higher praise than the fact that quite a few students indicated that they intended to continue using Google Docs or had already begun doing so. One student even reported that when another course required group work, he took the initiative to introduce Google Docs to his group as an additional means of collaboration!

References

Alexander, Bryan. 2008. “Web 2.0 and Emergent Multiliteracies.” Theory Into Practice 47, no. 2:150-160. ISSN 00405841. doi: 10.1080/00405840801992371.

Attewell, Paul. 2011. “The First and Second Digital Divides.” Sociology of Education 74, no. 3: 252-259. ISSN 0038-0407.

Becker, Henry J. and Margaret M. Riel. 2000. “Teacher Professional Engagement and Constructivist-compatible Computer Use.” Teaching, Learning, and Computing: 1998 National Survey, Report #7. Centre for Research on Information Technology and Organisations, University of California, Irvine. http://ed-web3.educ.msu.edu/digitaladvisor/Research/Articles/becker2000.pdf.

Benson, Denzel E., Wava Haney, Tracy E. Ore, et al. 2002. “Digital Technologies and the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Sociology.” Teaching Sociology 30, no. 2:140-157. ISSN 0092-055X.

Bruce, Bertram C. 2005. Review of Crossing the Digital Divide: Race , Writing , and Technology in the Classroom, by Barbara Monroe. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 49, no. 1): 84-85. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40009281. ISSN 1936-2706.

Greenhow, Christine, Beth Robelia, and Joan E. Hughes. 2009. “Learning, Teaching, and Scholarship in a Digital Age: Web 2.0 and Classroom Research: What Path Should We Take Now?” Educational Researcher 38, no. 4: 246-259. http://edr.sagepub.com/cgi/doi/10.3102/0013189X09336671. ISSN 0013-189X.

Greenhow, Christine, Beth Robelia, and Joan E. Hughes. 2009. “Response to Comments: Research on Learning and Teaching With Web 2.0: Bridging Conversations.” Educational Researcher 38, no. 4: 280-283. http://edr.sagepub.com/cgi/doi/10.3102/0013189X09336675. ISSN 0013-189X.

Nicaise, Molly, and Michael Crane. 1999. “Knowledge Constructing through Hypermedia Authoring.” Educational Technology Research and Development 47, no. 1: 29-50. http://www.springerlink.com/index/10.1007/BF02299475. ISSN 1042-1629.

Scardamalia, Marlene, and Carl Bereiter. 2006. “Knowledge Building: Theory, Pedagogy, and Technology.” In Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences, edited by R. Keith Sawyer. New York: Cambridge University Press, 97-118. ISBN 9780521607773.

Scott, Tony, Michael Cole, and Martin Engel. 1992. “Computers and Education: A Cultural Constructivist Perspective.” Review of Research in Education 18:191. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1167300. ISSN 0091-732X.

Smith, Aron. 2010. “Home Broadband 2010.” Washington, DC: Pew Charitable Trusts. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Home-Broadband-2010.aspx

Wynn, Jonathan R. 2009. “Digital Sociology: Emergent Technologies in the Field and the Classroom.” Sociological Forum 24, no. 2:448-456. doi: 10.1111/j.1573-7861.2009.01109.x. ISSN 0884-8971.

Zhang, Jianwei. 2009. “Comments on Greenhow, Robelia, and Hughes: Toward a Creative Social Web for Learners and Teachers.” Educational Researcher 38, no. 4: 274-279. doi: 10.3102/0013189X09336674. ISSN 0013-189X.

About the Author

Kate B. Pok-Carabalona is a doctoral candidate in sociology at the Graduate Center, City University of New York (CUNY). Her interests include immigration, race and ethnicity, comparative urban contexts, and the changing role and impact of technology; her dissertation uses in-depth interviews to examine how contexts structure the integration and subjective experiences of Chinese second generation immigrants living in Paris and New York. She has received funding from a Social Science Research Council (SSRC) summer grant, CUNY Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship, and a CUNY Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC) Fellowship. Kate holds a BA in History with concentrations in Classical History and Women’s Studies from Cornell University and an M.Phil.from the Graduate Center.

Notes