With two billion current users, the potential YouTube audience is huge and complex. In 2010, anthropologist Michael Wesch argued YouTube videos could reach millions of viewers, build participatory networks, enact change, and empower every voice. Now a few videos even reach billions of views. But while YouTube has embraced a social media culture that values “community, openness and authenticity,” this same “participatory culture is also YouTube’s core business” (Burgess and Green 2018, vii). View counts track both rhetorical and financial success in this massive digital marketplace, as engineers quit NASA for careers creating squirrel obstacle course videos. The competition for eyes is fierce: five hundred hours of video are uploaded every minute. And viewers are often fickle; twenty percent may leave if they are not hooked in the first ten seconds. Unintended audiences are complex too. Videos can anger or alienate family, friends, followers, colleagues, and employers. Copyright claimants can intervene to edit, monetize, or delete videos. Trolls lurk everywhere. And behind the scenes, YouTube/Google manipulates everything to maximize its profit and its power.

YouTube as a Site For Studying Digital Persuasion and Audiences

About sixteen years ago, new Web 2.0 platforms began to encourage mass audiences to join in new participatory and collaborative digital dialogues. In 2004, NCTE guidelines urged writing teachers to “accommodate the explosion in technology from the world around us” (7). A growing sense of urgency developed about the growing gap between school writing and students’ lives as digital composers and publishers (Richardson 2009, 5). Kathleen Yancey issued a “call for action” to writing teachers to “join the future” (2009, 1). Liz Clark argued that writing teachers faced a “digital imperative” (2010, 27). By 2014, Kristine Blair observed a “tectonic shift from alphabetic to multimodal composing at all levels of the writing curriculum.”

Some writing teachers began to focus on video and YouTube. By 2009, Brian Jackson and Jon Wallin saw the “informal, messy process” of “back-and-forthness” on YouTube as a model for teaching digital rhetoric (375). In 2010, Michelle Barbeau saw the powerful potential for YouTube as an object of study in college writing courses that could “appeal to digital natives, increase awareness of contemporary rhetorical communities, lessen the gap between teacher and student, and spark excitement in the classroom” (2). By 2013, Sarah Arroyo recognized that online video was “becoming the prototypical experience” of the internet, cultivating a culture that was “already permeating the institutions of our daily lives,” especially on YouTube; she called for a “participatory composition” pedagogy to interrogate that culture (2). In 2018, Christina Colvin found that assigning collaborative video essays offered her students broad opportunities to study process, mediation, and argument.

Since 2013, students in Sean Molloy’s college writing classes have been posting their “3-minute movie” video essays to YouTube and thinking about the kinds of audiences they might reach there. (Carissa Kelly posted her video in 2016.) In an informal longitudinal study, Sean has tracked the monthly view counts for all those students who chose to make their videos “Public.” He also shared the publicly posted videos with new writing classes, building an extended academic conversation about YouTube audiences. Gradually, our classes developed the YouTube audience model that we share here, together with some new insights based on Carissa’s case study of her video’s audiences using her data from YouTube’s creator studio. We offer this report of our eight-year conversation about reaching YouTube audiences as one way to transcend the constraints of the writing classroom and semester—while also critically examining Google/YouTube’s power to mediate access to these audiences.

Studying YouTube Audiences at Hunter and WPU 2013–2020

Sean began to ask first-year writing students to “reimagine” a text essay as a “3-minute-movie” in 2009. Most students submitted those movies on DVDs and the assignment focused largely on multimodal composing processes. In the Spring of 2013, Sean revived the movie assignment at Hunter College. In this “writing about writing” course model with an inquiry focus, students developed their own individual writing projects and research studies. They addressed the same thesis question for both a text-based and a video essay. Students posted all drafts to their own YouTube accounts. First and second drafts were all “Unlisted” to allow for teacher comments, peer review, and revision. Each student then chose whether to go “Public,” as well as how long to stay public after the semester. In Fall 2016, Sean brought the same writing course model and three-minute-movie assignment to William Paterson University.

Although they worked on other essays, many students at both colleges chose to reimagine their research studies as videos. We soon saw that many videos tended to move from inquiry toward direct arguments and/or public advocacy. Isabella (2014) challenged gender stereotyping in commercials. Hannah (2019) demonstrated the harmful effects of Cosmopolitan ads on young women. Rehma (2014) mocked stereotypical portrayals of Muslim families. Tanya (2014) concluded that Sean’s writing class did not meet all of Friere’s requirements for praxis. Ashley (2017) conducted a self-study to prove veganism can be affordable. Gregory (2013) argued against gender barriers in nursing. Meredith (2019) offered college students tips for professional success.

Composing, publishing and studying video essays changed how students saw themselves, their teacher, and their work. Sean offered extra credit to students who chose to go public and also to promote their movies to substantial audiences. Publishing videos for audiences beyond our classroom raised new questions. (Do I want my brother to see this movie about our dad? Will I lose followers? What will my boss think?) The video medium and the “movie” genre often allowed, suggested, or even required students to shift away from some constraints of academic/school writing. (Can I be funny? How do I add a creative commons or public domain soundtrack? How about animation? How many words can I put on text slides if viewers watch on phones? Can I create a mock movie trailer? Should I narrate face to camera? Should I add other faces or voices? How do I get informed permission? Should I use my real name?) Peer review exercises soon demonstrated that classmates were sophisticated consumers and creators of social media and video arguments with sharp instincts for adding power.

In 2013–14, many Hunter students chose not to go public. Over the years since, others deleted their movies, or relisted them as private/unpublished. But in March of 2021, eleven were still up and public; most were still adding new viewers.[1] For example, Nicole (2014) used her rhetorical analysis of dorm room decorations to explain Kenneth Burke’s ideas about arguments of identification.

Her audience has consistently grown since 2014. And a clear pattern has emerged: this serious academic subject draws more new viewers during the fall and spring academic semesters and fewer during summer and winter breaks (Figure 2).

Gradually, Sean began to see how the videos shattered the constraints of both the classroom and the semester. First, they reached growing audiences around the world for months or years. Second, the lessons learned from videos carried over to later semesters as new classes reanalyzed their situations and audiences. Third, we began to spread the conversation to other teachers and students. Between 2014 and 2021, six Hunter and WPU students have presented insights about their videos to groups of students and teachers. Sean also posted his related assignment on avoiding intellectual property and copyright problems to a CUNY graduate student website in 2014. He co-published a gallery of public student movies with introductions by the student composers in 2015. He published an online package of teaching materials for his “3-Minute Movie” assignment in 2016.

Our Fall 2016 Writing Class

Carissa took Sean’s first year writing course in Fall 2016. She was a new paraprofessional at a school for children and young adults with autism and she wanted to pursue teaching. While she enjoyed her job, Carissa saw students being treated in ways that didn’t make sense. A nonspeaking student was told to stop singing in class. A boy rocking in his chair was told to have a “quiet body.” A girl scripting to soothe herself was told to have a “quiet mouth.” Why suppress these students’ natural ways of communicating or interacting with the world? The answer was the Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA) therapy model used by the school. After doing some research on the topic and looking for the opinions of those in the Autistic community, Carissa learned that ABA was rooted in ableism, or “the discrimination of and social prejudice against people with disabilities based on the belief that typical abilities are superior” (Olson 2019). ABA therapy was developed from the 1960s through the 1980s by behavioral psychologist Ivar Lovaas who believed that “you start pretty much from scratch when you work with an autistic child. You have a person in the physical sense—they have hair, a nose and a mouth—but they are not people in the psychological sense… You have the raw materials, but you have to build the person” (Kronstein 2018).

Carissa thought Sean’s independent research project would be a good way to learn more about ABA. With her school’s permission, she conducted a rhetorical analysis of their in-house ABA procedures manual. She wrote a formal academic report, concluding that the ABA manual contributed to ableism in her school and published it to the website she created for Sean’s writing course, which she chose to make “Public.”[2]

With her classmates, Carissa watched some of the Hunter student movies and discussed the situations those students had faced. She chose to reimagine her ABA manual analysis as an advocacy piece, hoping to alert educators and parents about the potential harm from ABA therapy. Although she was passionate about the idea, she was still new to the topic and wary of sharing her criticism about such a widely accepted therapy, especially since her own workplace used it. Suddenly, the idea of “audience” was much more authentic: she risked losing her job if her bosses watched her video.

Carissa composed her video in four drafts. In the first draft, she talked through a plan on camera. In the second draft, she added a scripted narration, citing research and using technical jargon. Unable to include children due to ethical concerns, Carissa used her cats to model the therapy. In draft three, she used the cats more and moved them up to the first twenty seconds to hook viewers and lighten the overall tone. In this draft Carissa also cut the jargon way down, added citations to research studies to build credibility, and edited the running time down to 3:02. Small edits in the fourth (and final) version cut the video down to 2:43. After weighing the pros and cons, Carissa decided to go “Public,” expecting she would reach only a few dozen viewers.

Our YouTube Audience Model

As we learned more about YouTube audiences for our movies, Sean’s classes began to develop an audience chart model and revise it across semesters.[3] As the assignment developed over time, students read Laura Bolin Carroll’s (2010) “Backpacks and Briefcases,” together with the developing chart and a selection of student movies. (In the last year, Sean has assigned drafts of this article.) We quickly realized that these audiences were not separate tiers but one ecosystem—all interacting in different ways in each situation as soon as we click “Public.”

| Audience Types | Potential Size | Examples | Time Arc |

| Classroom | 1–20 | Teacher, Class | Days or weeks.

[Views end with semester.] |

| Promoted | 1 to 4000+ | Family, Friends,

Social Media |

Days.

[Views spike and then flatten.] |

| Sponsored

(Academic) |

30 to 300+ | Other Writing Classes

Teachers/Educators Other college students |

From time to time.

In person screenings [Views make small jumps.] |

| Intended/Ideal/

Target/Organic |

1 to 7000+ | Effective Agents (Bitzer)

Partners/Collaborators Affected Communities Academic Communities |

Months or Years.

[Views grow steadily.] |

| Suggested by Google/YouTube | 1 to 6000+ | Also Organic—but views are initiated by YouTube | Years

[Views grow in spurts.] |

| By Device | 1 to 7000+ | Mobile, Desktop, Tablet, TV, Game Console | Years. |

| Online Hostile | 1 to 200+ | Hostile Views,

Trolls and Haters |

Until you delete or go “Private”

But videos can be copied. |

| Real Life Hostile/Unintended | Not many but possible big impacts | Copyright Claimants, Employers, Family, Friends,

future life partners, etc. |

Until you delete or go “Private”

But videos can be copied. |

| Corporate | One | YouTube/Google | Google has it forever. |

Classroom Audiences

Most college writing assignments have an audience of one teacher and maybe one or two peer-reviewer classmates. Each student video starts with that audience too, first with teacher and peer reviews of drafts, and then in a “movie night” where creators introduce and screen their final movies to the whole class.

Promoted Audiences

If students go Public, they can also choose to promote their movie and build a quick base of viewers by the semester-end, perhaps also becoming more visible to search engines. A three-minute movie is often a lot easier and more comfortable to share on Facebook or Instagram than a ten-page study or essay, even one posted to a blog or website. But self-promotion to friends, family, followers, and work colleagues can feel trickier than sharing work with two billion strangers just by marking a video “Public.”

Direct promotion can also reach members of your intended audience. Abdus (2017) designed and ran a study that administered a “push” survey to warn fifty customers in his donut shop about the harmful effects of sugary sodas and sweetened coffees. His survey was effective: forty of fifty subjects (80 percent) chose a healthier drink.

But YouTube offered Abdus a chance to warn many more people. In a single week, Abdus used social media (with a big assist from his brother) to promote his video version of his study to over one thousand viewers. When Sean created a small winter-break promotion contest, Abdus added over 2,500 additional views. Even with 3,500 total views in its first month, this movie did not get much help from YouTube’s search and suggestion systems, and new views soon flattened out. In October 2019, another one of Sean’s writing classes decided to promote Abdus’s movie again as a team project; their promotion added another 270 views. In all, the three promotion efforts enabled Abdus to warn almost 4,000 people about harmful sugary drinks—all with almost no help from YouTube.

On the other hand, promotion may also push a movie toward unintended and/or hostile audiences. Carissa wanted to get her message out but she decided to not promote her video on social media where her coworkers might see it. It felt important to consider not just whether they saw it—but also how they found it. She did not want to appear to be pushing her criticism of a therapy they used in their faces. However, she saw less risk if they happened to come across it on their own.

Maybe Google/YouTube won’t suggest a movie with one hundred views to larger audiences. But some of our videos with a couple of hundred views have gone on to find new eyes month after month. At the same time, videos with only a handful of initial views (even excellent ones) often draw no new eyes over time. And even if a video’s audiences flatten out after a short promotional spike, reaching any real-world audience beyond the classroom is still a powerful choice that breaks free from the normal constraints of classroom writing.

Sponsored (Academic) Audiences

Every semester Sean shares old videos with new classes. This sponsorship creates a type of academic audience somewhere between promoted and organic. These students are not choosing to watch due to their needs and interests, except as a model for their own videos, a way to study audiences, and/or to get course credit. But they can be organic in some ways too. Carly’s (2016) study traced how her NJ high school failed to prepare students for writing expectations at a number of colleges. Many of Carly’s four-hundred–plus viewers have been Sean’s writing students. This past summer, Carly’s movie (with her consent) was added to WPU’s writing teacher resource website. This is, in one sense, another form of sponsorship by WPU writing teachers. But the line between sponsored and organic growth gets pretty blurry.

“Organic” Intended Audiences

When ancient Greek rhetors studied persuasion 2,400 years ago, their audiences and situations were small and simple. A persuader spoke to a single, visible “Public” or audience at one time and in one place. They could see each other and interact; they often knew each other; they had similar privileges, beliefs, and values. But as Phillip Gallagher (2019) notes, today’s digital audiences are far more complicated, “redefined by attributes of digital spaces and online communications.” Gallagher observes that as digital platforms “blur the boundaries between private and public domains,” they also splinter any single Public/audience into many different “knowledge cultures” each of which is an “organic assemblage of individuals into a group around a particular topic of interest.” Melanie Gagich (2018) also focuses on finding the ideal organic audience for any particular argument. She replaced an “imagined audience” assignment with digital composing and publication, which urged students “to address a ‘real’ community that they know from experience.”

Defining organic YouTube audiences early on (Who is this for? What work will it do?) has led students to often find multiple organic audiences. Like Gallagher’s knowledge communities, some of these audiences share a “topic of interest.” But others feel more like Gagich’s description of real communities that they know. For example, the intended audience for Sil’s (2018) anti-gang movie was complicated.

He wanted to warn young people and parents in his home town of Atlantic City, as well as families in similar communities. But he was also speaking to people who did not understand the struggles of families in towns like Atlantic City. A steady audience found Sil’s video every month for over two years. But in June 2020, as Black Lives Matter protests erupted across the nation and focused increased attention on the devastating effects of structural racism, Sil’s new views spiked up. He has again seen sharper growth in early 2021 (Figure 4).

Deanna’s (2019) conversation with her mom about converting to Judaism had, in one sense, a large potential organic audience of people considering conversion. But Deanna’s main purpose soon became to create an oral history for her own family. Nakia’s (2019) interviews about the “talks” black parents give their children to try to keep them safe also began with her family as her organic audience. But Nakia also promoted her movie to almost two hundred viewers at the end of our Fall 2019 class and its organic audience has grown slowly since, including a noticeable jump in the month after George Floyd’s murder.

The movie assignment can also draw audiences in “writing about literature” courses, at least in Sean’s horror-themed sections. But the organic audiences feel much closer to the “knowledge cultures” focused “topics of interest” proposed by Gallagher. These essays can discuss less serious issues of broad interest to large organic audiences of pop culture fans. Matt (2019) analyzes the monster in Bird Box (2019), arguing that it is H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu. He did not promote his movie and its audience grew slowly for two months. But starting in September, an audience began to find it and his monthly views increased for seven months before slowly declining in early 2021— possibly as interest in the Birdbox movie waned (Figure 5).

We have been surprised by how much of the organic audience growth for different movies is close to linear over months or even years. Sometimes organic audiences curve up for a few months or slowly level out. But we are also increasingly aware that explanations about audience growth based on real world factors must be understood as refracted and distorted through the sheer power that is exerted by Google itself. A closer look at Carissa’s audience growth since 2016 demonstrates this power.

Two Views of Carissa’s Organic Audience

In 2017, Sean could see Carissa find a growing organic audience. From March to September 2017, her growth rate was viral, climbing to over five hundred views a month. Then her rate of new viewers gradually declined, with a small surge in early 2021 (Figure 6). Sean could only guess as to why Carissa’s audience grew so quickly during 2017 and then slowed.

When Carissa studied the data available to her in YouTube’s creator studio through mid-2020, she was able to learn a lot more about how her organic audience found her video. YouTube breaks viewer sources into five key categories: YouTube searches, YouTube suggestions, external sources (like websites or Facebook), other YouTube features, and browse features (these last two are also suggestions and features inside YouTube.) The largest source of what YouTube calls “traffic” (3,765 of total 7,355 views) came directly from YouTube searches, most often “aba therapy.” YouTube’s suggestions to viewers of other videos generated 1,577 more views. (We discuss Suggested Audience below.) Carissa had hoped that audiences would find her video through searches. But she didn’t anticipate how much the internal YouTube searches and suggestions—as opposed to general Google searches or human referrals—would dominate audiences’ access to her movie. And it turned out that the YouTube search algorithm treated her video very differently over time.

External recommendations sometimes appeared to influence YouTube search results and suggestions. In January 2017, a Facebook advocacy group dedicated to “better ways than ABA” found and recommended her video which generated three small 2017 viewership bumps: about twenty in January, fifteen in May, and about sixty-five in August and September. (See the blue dotted line in Figure 7.)

Before the first bump, YouTube’s search, suggestions, and other features did not seem to offer or suggest Carissa’s movie to viewers. But right after the Facebook group voiced their support, new views from YouTube searches, YouTube suggested videos, and other YouTube features all spiked up (Figure 8).

YouTube’s support added significant new viewers, peaking in September 2017. Viewers from YouTube suggestions and other features dropped off after only a few months. But new viewers from YouTube searches decreased more gradually over three years as YouTube stopped including it in search results.

Later referrals from credible human sources did not revive the algorithm’s support. A George Mason University recommendation has added about thirty views every September, January, and May, coinciding with Fall, Spring, and Summer semesters beginning in 2018. Rutgers University and Seneca College also sent viewers to Carissa’s movie. Another external recommendation came from a Slovakian forum for expectant mothers which generated thirty-four views in May of 2019. In the end, this more detailed analysis reaffirms the power of YouTube as a bridge or a gatekeeper to Carissa’s organic audience.

Audiences By Device

Although this does not measure a kind of audience community, we were surprised when Carissa studied her own YouTube data that over half of her total views over four years were on mobile devices. Computer views were only 39 percent, with 8 percent on tablets and smaller slices on TVs and game consoles (Figure 9). We’ve added this category to the audience chart to inform future composing choices.

Unintended/Hostile Audiences

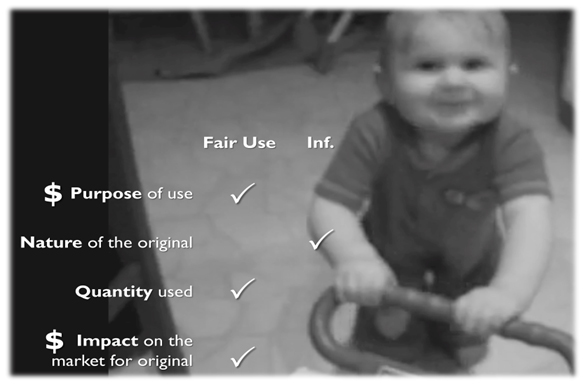

As creators and advocates, we often focus on organic audiences—the eyes we want to reach, the minds we can persuade to act, the people who can identify with our interests and struggles. But we have learned that thinking about unintended audiences can be just as important. Every creator who borrows content must consider possible copyright claims. Students who could not resist a Lady Gaga soundtrack or Disney video clip risked having ads inserted in their videos or having the videos muted or deleted. So, we review creative commons content, public domain rules, and murky “fair use” considerations. Both going “Public” and choosing to promote videos presses many students to think carefully about how people in both their real lives and in their online lives will react.

Trolls and haters have been an unavoidable part of YouTube’s ecosystem from its birth. Some harsh and even antagonistic comments can be forms of sincere engagement. But Burgess and Green observe that it has become evident in recent years that some trolls mount coordinated campaigns of disinformation or harassment, even “weaponizing” comments to silence diverse and progressive voices (2018, 120). They argue that learning to manage trolls, “both practically and emotionally, is one of the core competencies required” for successful YouTubers (2018, 119).

In theory, robust, heated, and even hostile comments may change how we think about the original videos as finite and fixed arguments by a single creator. But in practice, student creators/advocates may face abuse and trauma. The comments on Carissa’s movie started coming in early 2017. She expected opposition; in a way it marked her success. For a while, she tried to peacefully engage with skeptical and even hostile viewers, choosing to become a public advocate in a new way. But she soon became overwhelmed and took a step back. Returning months later, Carissa noticed that the comment section had taken on a life of its own as her viewers began to debate each other. To this day, the comments grow with new debates, even though Carissa has not rejoined them.

Suggestions and Our Corporate Audience: YouTube/Google

Purchased by Google in 2006, YouTube is an arm of one the world’s largest four corporations, with Amazon, Apple and Microsoft. Together These “big four” dominate internet commerce and our digital lives. In 2017, John Herrman criticized the ways in which these “all-encompassing internet platforms” assume innocent “costumes of liberal democracies,” while they are in fact “always a commercial simulation,” inducing us all to entrust increasing portions of our “private and public” lives to “advertising and data mining” firms. In this complex new reality, we two billion users are also two billion products. YouTube/Google mines our data to sell targeted ads and instant purchase buttons—earning $15 billion in 2019 (Duffy 2020).

YouTube always fills your screen with suggested videos to lure you to stay on the platform as long as possible. As Carissa’s video began to find its organic audience, YouTube began to suggest it to viewers of similar videos. Over time, what YouTube describes as “views from suggestions appearing alongside or after other videos” added 1,577 viewers, her second largest audience. We realized we had not considered this side to YouTube’s “participatory culture.” Classroom views are mostly initiated by the teacher. Promoted views are initiated by the creators, their families, friends, and followers. External recommendations come from interested communities. Google and YouTube searches are initiated by organic audiences—even if Google controls the actual search results.

But video suggestions are initiated directly by Google. Like any other form of promotion, that is partly a good thing for creators who can reach more eyes. Carissa’s video appeared alongside suggested videos that were also questioning the use of ABA, most notably the video, “Is ABA Therapy Child Abuse?” But the degree of control that YouTube exercises over its suggestions is a troubling reminder that the most important, powerful audience on YouTube is often YouTube itself.

Conclusion

Over eight years now, we have learned a few things about YouTube audiences and how we can think about them in useful ways. We are happy to share that here, maybe as a starting point for further discussion, or for similar conversations about digital audiences. We continue to learn every semester and we welcome creators in other classrooms to join us in thinking about these and similar questions. How do we balance public digital advocacy and protection from abuse? How do we assert our fair use rights in systems that give so much power to copyright claimants? How do we resist and oppose the power of Google to limit our audiences, even as we use its platform and tools? How can we build similar classroom conversations on other platforms that reach thousands of eyes?

We have not unlocked Google’s search algorithms to figure out how to turn serious college video essays into viral sensations. Google/YouTube suggests that the success of our videos is in our hands, based essentially on the quality and rhetorical sophistication of our work—even as it only vaguely describes its “search and recommendation systems [as using] hundreds of signals to determine how to rank videos.” Of course, quality and persuasive power do matter. And adding enticing titles, interesting thumbnail images, compelling video descriptions, thorough lists of tags, and other searchable metadata—all that may help too. Promotion to build an early audience has often seemed to matter for us, although a few videos (like Carissa’s) still find growing audiences with very little creator promotion.

But Carissa’s case study of her video also demonstrates that Google/YouTube’s algorithm computers are faithless friends. YouTube did not promote her video. Then it did. Then it didn’t. And those mercurial decisions held great power: at least 83 percent of her total audience through March 2021 has been due to Google/YouTube referral sources. YouTube is a rigged game, and it is the only game in town. As critical thinkers and creators, we keep that reality in mind as we call it out and resist it.

Yet, we also remain excited and hopeful. This flawed corporate platform still gives all of us a chance to reimagine the work we do in writing courses and why we do it. We can practice and study how to compete to reach audiences far beyond one teacher, one classroom, one semester, and one college. We can all publish work that may find a growing audience around the world for years to come.