As we envision the digital futures of books, manuscripts, and archives, there is no substitute for historicization: books and manuscripts are technologies too, and foregrounding this perspective allows us to contextualize our work with digital facsimiles, metadata, and resources. This conversation far predates our current moment of digital profusion; in Orality and Literacy (1982), Walter J. Ong compares Plato’s critique of writing to contemporaneous critiques of computation, noting that “once the word is technologized, there is no effective way to criticize what technology has done with it without the aid of the highest technology available.” Ong continues, arguing that this technology is not “merely used to convey the critique” but rather brings “the critique into existence” (78). To corroborate this: when we explore the implications of our material history, our work increasingly, though not exclusively, occurs within or alongside digital context. We write about rare and archival materials in digital spaces, create digital repositories of items, and use digital methods to analyze documents, from transcription services to x-ray spectroscopy. Yet handling, working with, and conceptualizing primary source materials are skills that can be gained through a combination of experience and instruction. Forms of digital access to these items do not circumvent the need for these skills, but only expand their value.

While there are decades of research on the concept of information literacy, the idea of “primary source literacy” is relatively nascent both as a professional term and as a template for specific pedagogical strategies (Carini 2016, 191). Elizabeth Yakel and Deborah Torres’ “AI: Archival Intelligence and User Expertise” (2003) posits an influential three-part standard: domain or subject-focused knowledge, artifactual literacy, and the idea of “archival intelligence,” which consists of understanding archival theory and practices, negotiating strategies to handle the ambiguity of primary sources, and creating meaning from the artifactual or material qualities of a source. In addition, professional organizations for libraries such as the Society of American Archivists (SAA), the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) and ACRL’s Rare Books and Manuscripts Section (RBMS) have formed a “Joint Task Force on Primary Source Literacy” (2015), whose guidelines have been approved as of 2018. These guidelines, which consolidate decades of work among information professionals in these organizations, attest to the growing importance of quantifying and understanding the ways in which we teach within special collections, archives, and libraries.

Today, teaching techniques that animate these guidelines are most visible in case studies or digital toolkits (such as Brooklyn Historical Society’s “Teach Archives” in 2013), designed to illuminate the pedagogy of specific institutions, as well as the Society of American Archivists’ recent publication series, “Case Studies on Teaching with Primary Sources (TWPS)” (2018), which animates the “Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy” by the same organization. These resources are often extensive, such as Using Primary Sources: Hands-On Instructional Exercises (Bahde, Smedberg, and Taormina 2014), a text designed to share both activities and types of learning goals across a range of collections and populations (vii). These techniques and examples often emphasize hands-on, lesson-based learning, as opposed to presentations or “show-and-tells” that exhibit materials but do not provide instruction on how to analyze them or access them in the context of a research visit. As embodied by Past or Portal?: Enhancing Undergraduate Learning through Special Collections and Archives (Mitchell, Seiden, and Taraba 2012), the increasing volume of specific case studies across materials and institutions contributes to the robust conversation on pedagogy in special collections, particularly at the undergraduate level. However, beyond resources such as the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) report, Terra Cognita: Graduate Students in the Archives (2016), which surveys the findings of the CLIR Mellon Fellowships for Dissertation Research in Original Sources, few resources or literature exists for teaching primary source literacy to graduate populations, especially in a multidisciplinary context.[1]

At the graduate level, students often seek basic training that echoes aspects of Yakel and Torres’ (2003) idea of primary source literacy and includes negotiating materials in special collections and archives, navigating catalogs and finding aids that are primarily hosted in digital spaces, and managing information and notes once in the reading room. The types of questions that accompany graduate-level primary source literacy align with Yakel and Torres’ concept of “archival intelligence,” and are enumerated in the CLIR report Terra Cognita (2016): “Navigating Institutions,” “Negotiating Expectations,” “Documenting Processes,” and “Finding What You Need”—all essential aspects of archival research that involve technical knowledge, critical thinking, project management, and interpersonal skills. However, particularly in fields with a strong theoretical component, or in programs that require teaching, graduate students are also often primed for conversations not just on resources or skill development but also on special collections pedagogy itself. Special collections-based classes with graduate students are not just an opportunity to impart skills or information, but to critically examine “the archive” as a theoretical, conceptual, and literal space. As a result of the so-called “archival turn” in literary studies, for instance, sparked in part by Jacques Derrida’s Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression (1995), the idea of the archive, which graduate students often theorize in their work, may have little in common with an institution they visit to conduct research that is staffed by humans (not theories), with unique management and custodial procedures, reflecting a history all its own. In particular, scholars and archivists have different stakes in their definitions of what constitutes an archive or special collection, and how these sites signify critically, conceptually, and literally. By speaking across these disciplinary boundaries, we can more equitably offer credit and share responsibilities for making the material traces of history visible and accessible to those who need them. And given the critical possibilities of this interaction, special collections pedagogy stands to benefit from a model in which knowledge of primary source work is not just transmitted, but actively co-created with a highly proficient and critically engaged population.

To frame key features of critical pedagogy specifically for work in special collections,[2] we might consider the standard “show-and-tell” class visit, in which a librarian or curator imparts information about objects on display, as an example of Paulo Freire’s “banking model” of education from his canonical Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970). In this model, knowledge is “bestowed” by those in possession of it unto those who do not, and students may only participate in “receiving, filing, and storing the deposits” of knowledge they are granted within the educational context (72). While these “show-and-tells” often have a highly affective component—since generally the most striking or historically important objects are featured, which can feel special or exclusive—they rhetorically foreground a teaching model in which the instructor is the gatekeeper or expert, and students the initiates. This model, based on explication, is the target of Jacques Rancière’s The Ignorant Schoolmaster (1987), in which he argues that a student who “is explained to” is susceptible to submit to a “hierarchical world of intelligence,” in which an explanation can always be obtained or offered as superior to the student’s own intuition and research (8). Rancière suggests that by explicating, instead of fostering the development of communal knowledge and conversation that he terms “universal learning,” we may well reinstate hierarchies of knowledge that certainly apply to the special collections reading room and should be challenged: the trope of the omniscient librarian, or the equally inaccurate librarian who solely pages items without interest or understanding.

If we consider the dynamic of the reading room—the physical space in which archival encounters occur—they are not dissimilar to the hierarchies of access that Rancière (1987) describes within learning: the uneven distribution of knowledge in the room, the presence of obstacles or facilitators that mediate the flow of materials that may yield knowledge, the differing institutional and disciplinary vocabularies on either side of the reference desk. Many of these discrepancies may have practical and professional purpose; for instance, security considerations require material to be distributed according to certain protocols, and standards for metadata and cataloging are often in place to facilitate physical access and storage of materials. In addition, many misperceptions about the figure of librarian or archivist as all-knowing or gatekeeping conceal the fact that staff often work with little resources, within hierarchies of supervision, and in light of their own interests or challenges regarding the material in their care.

However, the presence of these limitations offers us critical possibility, and likewise opportunity to re-examine their usefulness as policies. For instance, Patrick Williams’ (2016) work on critical library pedagogy cites Audre Lorde’s exhortation to examine not just books, but also our interactions with them, and asks what possibilities might unfold if we approach special collections work in this embodied way (111). Continuing in this critical pedagogical vein, we might also consider Rancière’s (1987) idea of intelligence as “the power to make oneself understood through another’s verification,” which includes dialogue, participation, and experimentation (73). Together, these theories suggest that rather than a pedagogical model that views student knowledge, particularly at the graduate level, as deficient and in need of augmentation, teaching models within special collections might collaboratively cover the technical basics expressed by Yakel and Torres (2003)—such as negotiating discovery systems, reading a finding aid, or mastering a research statement in the reference interview—while also allowing students and facilitators to build and develop collective knowledge that addresses both practical and conceptual considerations for primary source work in a digital era. In doing so, we can reframe teaching and outreach as acts of equity and access, expanding the historically narrow range of who feels empowered to conduct primary source work.

In what follows, I will suggest how this teaching model applies specifically to interdisciplinary graduate populations, and will discuss the technical and conceptual underpinnings of a year-long project titled the “Collaborative Research Seminar on Archives and Special Collections,” conducted with staff and support from the Graduate Center, CUNY and the New York Public Library. This project entailed numerous group meetings to discuss institutional partnerships, pedagogy, and student research, and culminated in two two-hour long seminars each semester, each hosting under twenty students, faculty, and staff that had been selected by application. While many aspects of this project used digital platforms—for promotion of the event, for applications, for communicating with participants, for locating relevant materials, and for follow-up communication with participants who elected to write blog posts about the experience—the core of this program was conversational, in-person, and interactive with materials. And after Ong’s (1982) discussion of using the highest technology available to understand those prior, this project uses digital methods—such as this article, as well as student blogs—to make its non-digital elements visible. Not as a preliminary to digital work, but as an essential interlocutor for it, the Seminar focused on cultivating the in-person conversations, relationships, and experiences that prepare participants for confident and critical engagement with primary source materials. Thus, I present this project as a case study, for the specificity the genre offers, but also invested in developing a pedagogical frame that considers two core principles—conversation and experience—that allow us to not only impart primary source literacy skills, but also reconsider the possibilities of what counts as “research” in our embodied encounters with primary sources.[3]

The Seminar

Background

The Collaborative Research Seminar on Archives and Special Collections began as a project in the spring of 2017 to engage graduate students, faculty, and staff in academic and cultural institutions with primary source research methods, and to increase dialogue between the Graduate Center, CUNY, and the New York Public Library.[4] In early 2017, I developed the idea for the Seminar with Alycia Sellie, Assistant Professor and Associate Librarian for Collections at the Graduate Center, CUNY, as well as subject specialist for the English program. Adam Rosenkranz, Gale Burrow, and Lisa Crane (2016) at Claremont University, who document their own “Primary Source Lab Series” begun in 2012, cite this type of collaboration—between subject specialist and librarians—as an effective model for graduate-level primary source teaching. However, like many projects, this one began not with a literature review but with an immediate concern: as a specialist, my daily work consisted of collaborating with a variety of researchers and materials, while my evenings were spent working as a graduate student in the Graduate Center, CUNY’s English Ph.D. program. I wanted to consider a structure to share my experiences as a library specialist with my academic colleagues and also to create a platform for my Library colleagues to share their expertise, ideas, and sentiments about their work. This commitment to representing voices across institutions was comprehensive, and involved a Seminar committee that included the Graduate Center Library’s Alycia Sellie, Roxanne Shirazi, and Polly Thistlethwaite, the New York Public Library’s Jessica Pigza and Thomas Lannon, faculty advisors Ammiel Alcalay (Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative) and Duncan Faherty (The Early Research Initiative), the Center for the Humanities’ Kendra Sullivan and Sampson Starkweather, and Matthew K. Gold and Lisa Rhody from Graduate Center Digital Initiatives. Together, the committee negotiated pedagogical structure, the application process, and decisions that ultimately contributed to the collaborative nature of the program.[5] The Seminar was designed for the needs of an interdisciplinary and varied applicant pool, with the perspectives of numerous committee members, facilitators, and participants whose work addresses academia, radical archives, publishing, and special collections librarianship. As Marcus C. Robyns (2001) indicates, teaching primary sources beyond discipline-specific skills and knowledge allows us to envision “the archives [as] not only a repository of the past but also a challenging center of critical inquiry” with multiple interlocutors and facets, and the Collaborative Research Seminar sought to create an experience that spoke to this concept (365).

A key part of the Seminar’s pedagogy took up the primary source principles of Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative, begun in 2010. This publishing initiative, under the editorship of Ammiel Alcalay and consulting editorship of Kate Tarlow Morgan, in conjunction with staff from the Center for the Humanities, connects doctoral students and guest editors with projects that explore the archives of under-published and underrepresented authors of the twentieth century, as well as lesser or unknown aspects of well-known authors. The results are published annually and draw on a variety of authors from Langston Hughes to William S. Burroughs, Kenneth Koch to Toni Cade Bambara, Diane di Prima to Ed Dorn. As editor Megan Paslawski (2013) notes, the principle of Lost & Found is to “follow the person,” an ethos that Alcalay and the editors take literally—as in, visiting poets or the unexpected institutional and personal places their works lead—and also archivally. Instead of privileging scholarly conversations and secondary knowledge that categorizes materials, Lost & Found editors are encouraged to listen closely to the documents, engaging what their primary materiality might mean (8). Given Rancière’s (1987) Jacotot, whose teaching method rests on distributing literature and then engaging with it closely, carefully, and extensively without explication, Lost & Found’s exhortation to “follow the person” models a mode of both pedagogy and academic research centered on fidelity, community, connection. As Paslawski (2013) notes, this method “allow[s] more than words to be found” in its requirement that we examine what is there, listen to it on its own terms, and forsake traditional narratives about materials for the paths they indicate (9). This method encourages a different practice of engaging with archival materials, by fostering personal relationships with heirs and literary estates, former colleagues, and other archivists, editors, and scholars to generate new insights and interest in the subject. In particular, this entails “rescuing” literary figures from the way they have been historicized (or forgotten), in order to understand the person who actually was, and restoring the live-wire network of authors and collaborators instead of siloing authors by style or literary movement. While Lost & Found focuses on twentieth-century poetry that might broadly be considered as part of the New American poetry milieu (even as it challenges the value of such a categorization), its methods are applicable to a variety of primary sources—many of which we examined in the Collaborative Research Seminar itself.

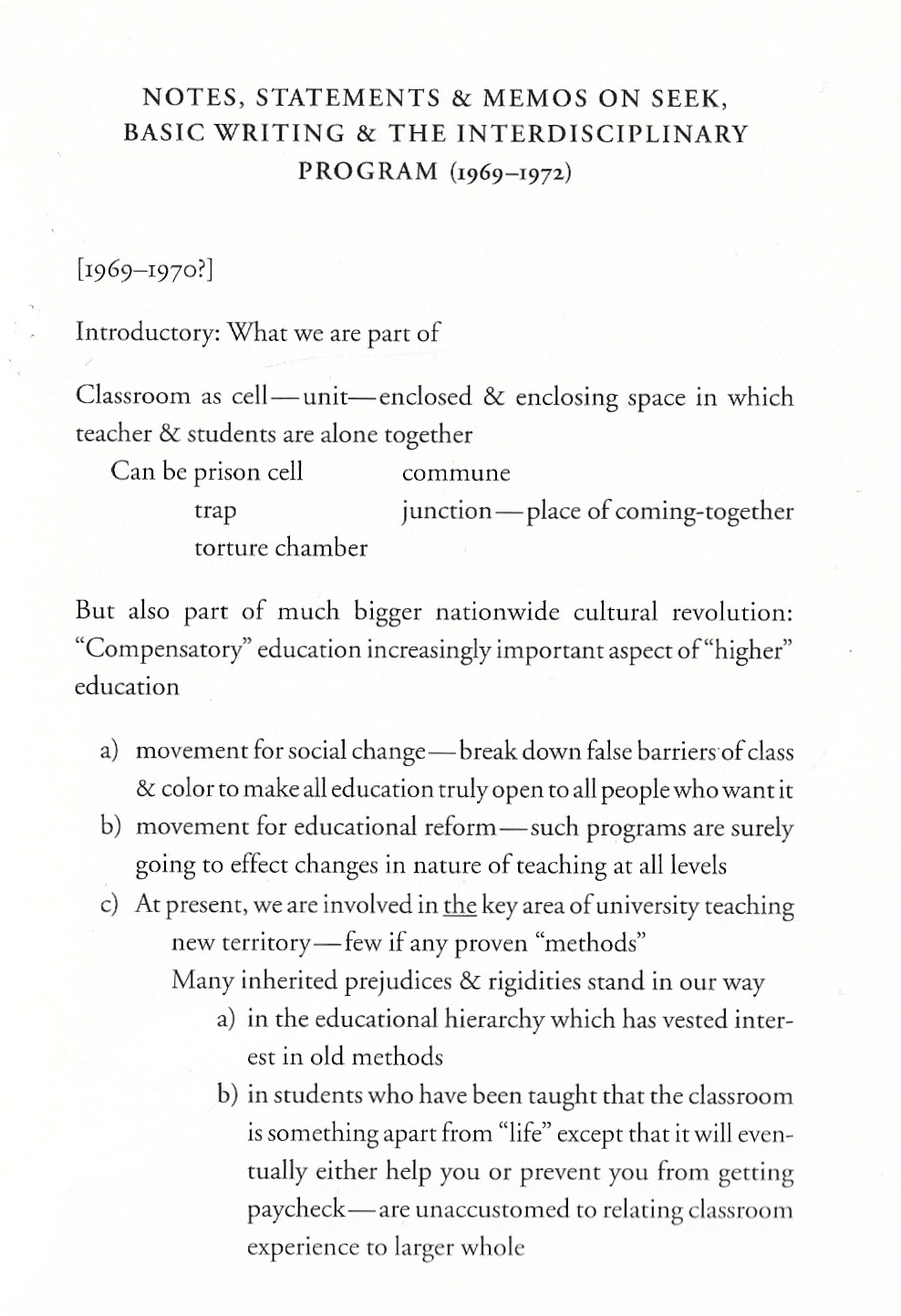

As an essential teaching resource, Lost & Found has published archival materials on pedagogy that were generated by poets who taught at City University of New York, including Adrienne Rich, June Jordan, and Toni Cade Bambara. These poets were hired as instructors by Mina Shaughnessy, the Director of the CUNY SEEK Program (Search for Education, Elevation, and Knowledge) in the late 1960s. This program, which came to City College in 1965 as a pre-baccalaureate program, sought to provide additional instruction and educational support to students from a more diverse range of communities, and to increase the percentage of African-American and Puerto Rican students at City College (Rich et al. 2013, 1). In a chapbook of her archival materials from this era, Lost & Found editors include quotations by Adrienne Rich of Paulo Freire, among numerous other critical pedagogy voices, as she writes her own powerful methods of teaching. In her “Notes, Statements & Memos on SEEK, Basic Writing & the Interdisciplinary Program (1962-1972),” Adrienne Rich writes of her class English 1.8:

The problem for the teacher is to make the term’s work supportive and relevant for each and every student: to help dislocate ‘blocks,’ to open possibilities of expression, to help each student as much as possible to become the kind of writer he is meant to be. It is not simply to turn out 15 people who can pass the English proficiency examination, although we hope that that will inevitably result. (Rich et al 2013, 18-19)

While Rich’s subject is writing, this type of pedagogy is widely applicable. Rancière (1987) expresses similar sentiments—“the problem is to reveal an intelligence to itself”—but Rich’s model is distinctly expressive and supportive, beyond a baseline of fostering student self-motivation and independence (28). As with the Seminar, we might think beyond activities designed to produce proficiencies (like Rich, while acknowledging that these are essential), but look ahead to the outcome of fostering the unique type of primary source researcher our students want to and need to be. As with Rich’s pedagogy, this type of mentorship is an act of equity in its potential to expand who believes themself to be a writer, or an archival researcher—and thus, a custodian and author of our material history.

Implementation

As with any conversation on pedagogy, theoretical robustness depends on good implementation: this starts with understanding both learning goals and student needs. To learn more about self-reported student needs and interests, as well as manage enrollment numbers, the Seminar began its pilot year with an application process. Both the Graduate Center, CUNY, and the New York Public Library are considering how to contribute the resources necessary to continue, given that 117 students, faculty, and staff from primarily the Graduate Center, CUNY applied over the course of the pilot year in two application cycles. The volume of applicants attests to the need for this type of programming, and while the demand for the Seminar far exceeded our instructional capacity at the time, I connected with all applicants to provide additional resources and support for their work.[6] Expressing interest across a wide swath of disciplines, skill levels, and even academic status, the application results of the Collaborative Research Seminar foregrounded the need for pedagogy with an interdisciplinary audience in mind. Given that most case studies for special collections pedagogy focus on class-specific visits that have a set subject or topic, the Collaborative Research Seminar explores a teaching model that challenges us to give voice to interdisciplinary archival experiences.

The first iteration of the Seminar in Spring 2017 was hosted jointly at the Graduate Center Library and the Brooke Russell Astor Reading Room of the New York Public Library, with a cohort of 12 participants selected from 58 applicants. The second iteration involved 19 participants from 59 applicants, as an experiment to determine scalability of the pedagogical model. Most of the participants were graduate students, with one or two faculty members at each Seminar; the committee decided to prioritize graduate student applications and work towards a different model to specifically address the different needs of faculty. All participants from both sessions were given the opportunity to publish a blog, funded by the Center for the Humanities, about their experience and the items they examined at the New York Public Library, and to join the working group Primary Source, also through the Center for the Humanities. Given also the inability of the program’s structure to accommodate all applicants due to staffing and resources—a conflict at odds with the very mission of the program to increase access to special collections work—much remains to be seen as to the possibilities of this model.[7]

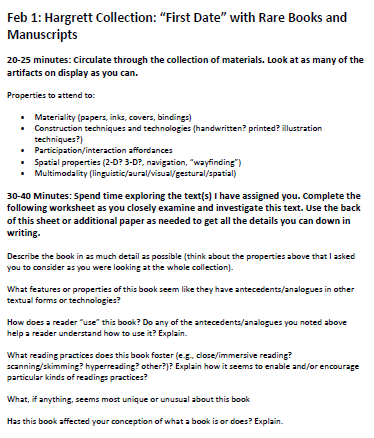

Each Seminar consisted of two sessions—held for two hours in the evening, two weeks apart. The first session was hosted by the Graduate Center Library and oriented participants towards specific questions and concerns in archival work. The second session was hosted in the Brooke Russell Astor Reading Room at the New York Public Library, and consisted of hands-on experiences with collection holdings. I worked with staff from the New York Public Library to curate objects from the second session in response to conversations and feedback from the first session, either around an area of research interest or a theme in archival work. Each session concluded with a short exit survey that participants completed on paper, containing basic response questions, including hopes for future sessions or information that was helpful or still being digested. To accommodate the variety of skill levels in the Seminar, participants also received a sheet on how to handle special collections material, as well as a hand-out on other Graduate Center and New York Public Library collections and resources available to them as their research progresses.

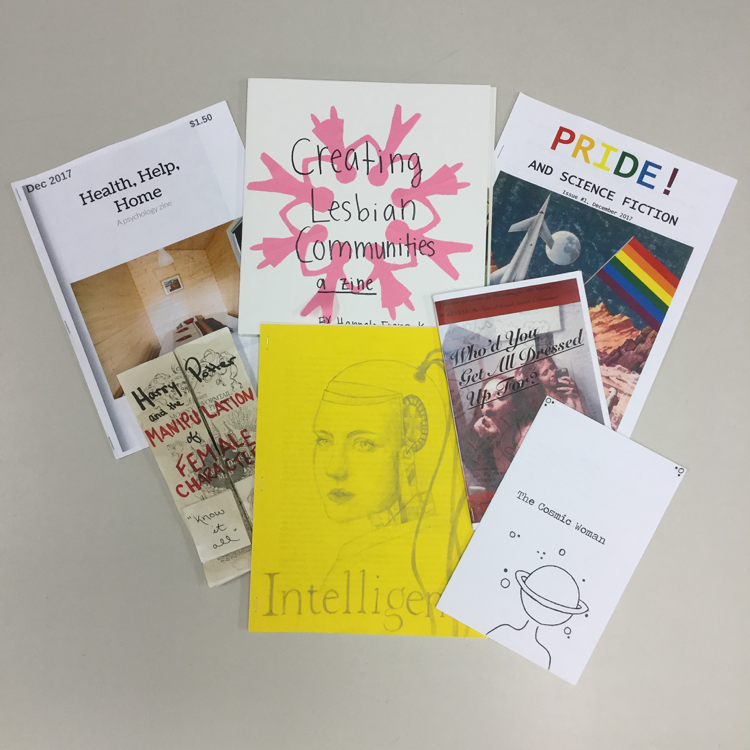

In the Spring Seminar, with a cohort of 12 students, Alycia Sellie and I led the initial session of the first Seminar with an open-ended discussion on archival work. Topics discussed included challenges with finding relevant resources, negotiating expectations in reading rooms, and collaborating with archival staff. The session concluded with small group work browsing NYPL’s Archives Portal and digital catalog to find items of interest for the second session. Participants wrote suggestions for second session on notecards and submitted them before leaving. After a debriefing meeting that included feedback from the Seminar committee, I worked with Thomas Lannon and Jessica Pigza to lead the second session. Using New York Public Library collection materials from multiple curatorial units, we conceived of research tables as “stations” that addressed specific fields of knowledge or types of archival materials—including institutional records, books and annotation, serial publications, family papers, lightly processed archival boxes, and others. Items were arranged by their designated theme on a table, where participants were invited to rotate either solo or with colleagues to examine the materials. After rotating through stations, participants reconvened for a large group discussion about materials they encountered. The session ended with completion of feedback forms, and an invitation for participants to stay involved by writing a blog post or joining the working group for Primary Source at the Center for the Humanities.

The Fall Seminar operated on a similar principle, although with a slightly larger cohort of 19 participants. In advance of the first session, the Collaborative Research Seminar committee distributed a list of readings to participants to assist in framing their Seminar experience, including introductions to the field of archives as well as accounts of specific experiences with primary source work (Appendix A). To accommodate a larger cohort of students, the first session drew on the rotating station model of the second session of the first Seminar. Staffed by Meredith Mann (NYPL), Tal Nadan (NYPL), Alycia Sellie (GC CUNY), Roxanne Shirazi (GC CUNY), Thomas Lannon (NYPL), and myself, the rotating stations covered four main themes. These themes, collaboratively developed and inspired by Roxanne Shirazi’s sharing of the CLIR report Terra Cognita (2016), included “Navigating Institutions,” “Negotiating Expectations,” “Documenting Processes,” and “Finding What You Need.” Participants rotated through the first three stations for short amounts of time, and then remained as a whole group in the final station—an exploration of archival vocabulary, New York Public Library discovery tools, and a working session where the group populated a shared Google Doc with items of interest as a way to experiment with collections discovery. The relatively high ratio of facilitators to participants allowed for a variety of pedagogical approaches within each station—from small activities to open discussion—as well as offered participants an opportunity to meet and connect with librarians at the Graduate Center and the New York Public Library.

The second session of the Fall Seminar followed the model of the Seminar’s first iteration, featuring a series of curated stations designed around groups of documents from the New York Public Library’s curatorial units of the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building. After rotating through a few stations, either collaboratively or solo, participants convened for a larger follow-up discussion. The session ended with completion of feedback forms, and an invitation for participants to stay involved by writing a blog post or joining Primary Source at the Center for the Humanities.

For both of the second sessions of the Seminar, material selection was an especially important component. We sought to not only choose generative items that spoke to multiple research possibilities, but to create a pedagogical framework in which participants could encounter these items with as little predetermination as possible. Given the interdisciplinary nature and varied skill levels of the participants, the principle of “listening closely” to documents on their own terms was key to the success of the hands-on portion of the Seminar. This was accomplished in part by mitigating expectations: in the application phase of the program, we asked participants to submit research interests, but reinforced that the Seminar was not a reference consultation and they were likely to encounter materials that did not speak to their current research topics. This openness was also facilitated by the manner in which participants were invited to encounter the materials themselves in the second session—by roaming from table to table, alone or among colleagues, for suggested ten-minute intervals.

Curated stations in the reading room had minimal didactics, generally only including a small slip that indicated whether or not items could be photographed for online distribution (as on social media networks, such as Twitter). For some archival materials, we would supply the finding aid or the catalog record as an additional object on the table in its own right, to facilitate the iterative practice of negotiating the physical object alongside its metadata. Participants were encouraged to learn about the materials in this exploratory manner by speaking with the session’s facilitators and their colleagues, as well as being attentive to the nature of the encounter itself, beyond how the item might apply to their specific research. We ended the second session with a framing discussion, that allowed us as a group to consider the possibilities and limitations of such an interdisciplinary openness to materials, and what types of encounters encourage increased comfort and skill with primary source work.

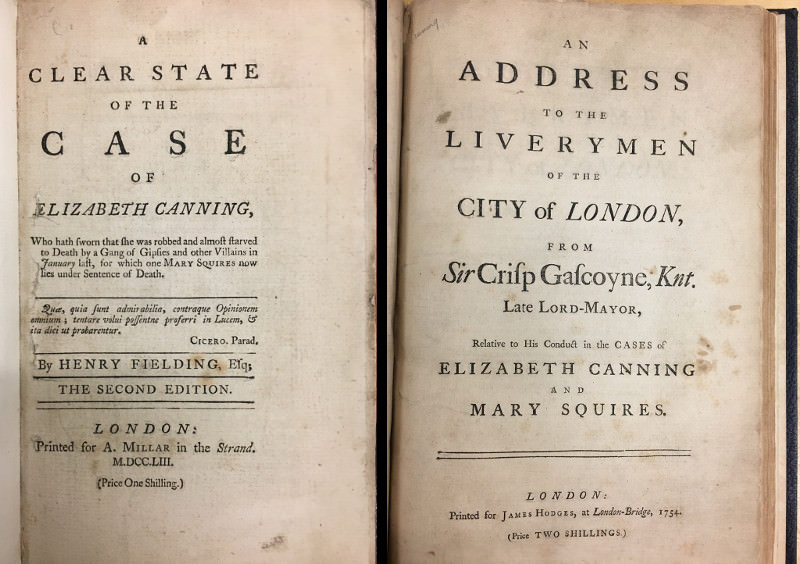

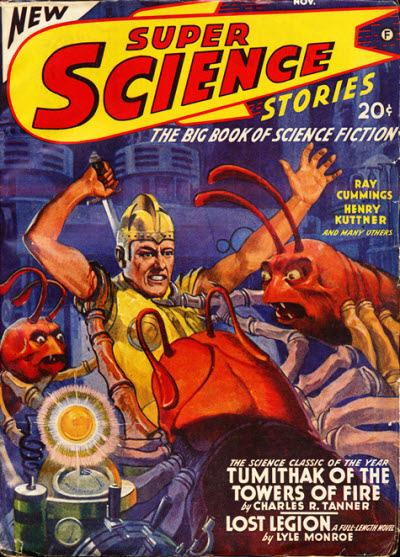

Specific examples of collection items from the first Seminar included Isaac Newton’s assistant’s edits on the Principia (1687), Wallace Berman’s innovative literary mail-magazine Semina, Sylvia Plath’s annotations of The Four Quartets, a copy of William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair as a book-in-parts, Patti Smith’s notebooks juxtaposed alongside nineteenth-century commonplace books, a single box from the Timothy Leary Papers, Noah Webster’s correspondence with his daughters, among many others. These items, which range from rare books to periodicals, archival material to unique manuscript items, offered participants a variety of archival encounters to experience and discuss. Likewise, in the second session, selections included Muriel Rukeyser’s reading notes on Willard Gibbs, a collection of archival research done by Rukeyser; the mimeographed biweekly magazine, The Floating Bear, edited by Diane di Prima and LeRoi Jones; the San Quentin execution register; photographs by Jessie Tarbox Beals of the Health School at P.S. 40 in New York City in 1918, from the People’s Institute records; affidavits and inspector’s reports from Brooklyn and East Harlem from the Committee of Fifteen records; as well as documents relating to early printing in Peru, 1584-1628. Each of these stations presented a range of materials that, whether or not they directly addressed participants’ research field, afforded increased experience with the first steps of meaning-making with primary sources—to look closely, and listen to the documents.

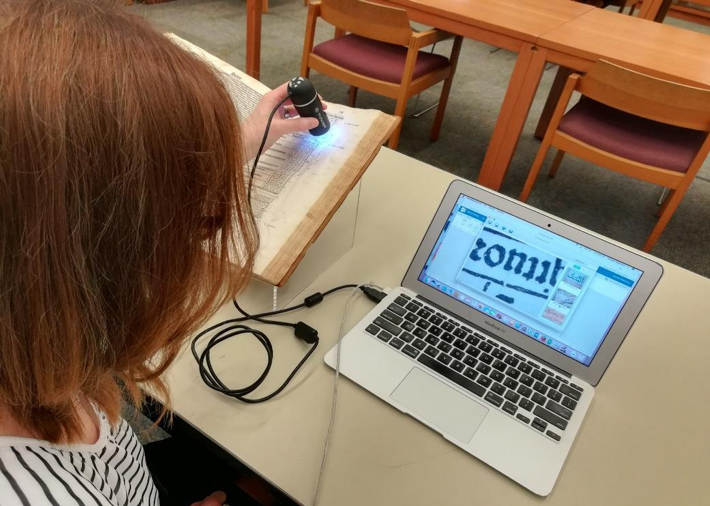

This type of close attention was modeled in multiple ways across a single collection. The New Yorker records station, curated by Tal Nadan and Meredith Mann, contained a typescript of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and letters to the editor in response, a print copy of The New Yorker from the Library’s general research division, and a computer opened to the New Yorker Digital Archive database. Here, we encouraged participants to think of the different digital and paper materialities of these items and how they might serve varying forms of research. For instance, sometimes a searchable database of digitized items is far more expedient than searching individual items, depending on the research question. Through printouts of the digital catalog records and discussion of digital resources, we sought to underscore how different materialities address different research needs.

With material selections for special collections teaching, it is difficult to avoid the act of curation, which is traditionally associated with the “show-and-tell” format. Expertise and knowledge of collections is a valuable pedagogical resource, to frame disciplinary and methodological approaches to materials widely, as well as suggest the sheer variety of encounters that can occur in special collections. While the very act of creating stations constituted curation in the Seminar’s pedagogical model, the approach to material selection in conversation—noting its arbitrariness, its relationship to a librarian’s personal interest, and its value as an example of a type of record group—opened the idea of selection for questioning. In this way, by understanding that one must start somewhere for hands-on primary source work but that this act nevertheless predetermines the experience, the pedagogy of the Seminar used discussion to reframe and question the authority of material selection.

The final aspect of each iteration of the Seminar was post-assessment, a practice that is encouraged by Anne Bahde and Heather Smedberg (2012), who advocate for “measuring the magic” as an essential component to facilitate primary source literacy and build on Esther Grassian and Joan Kaplowitz’s (2009) instructional literacy assessments of reaction, learning, and performance assessments. These translate to three rhythmic questions: “did they like it?” “did they get it?” and “can they do it?” (156). To address this, the Seminar used a questionnaire assessment, which entailed completion of a paper exit survey after each session. For the initial session, questions focused on clarifying learning objectives and understanding how participants felt about the experience, and for the second session, the questions focused on the entire Seminar structure more broadly.

In terms of “did they like it”: all participants said they would recommend the program to a colleague, and when the second Seminar cohort was asked if their likelihood of using New York Public Library materials increased as a result of the Seminar, all answered affirmatively. The question of whether participants “got it” creatively appears in the resulting blog posts published through the Center for the Humanities, which I will address shortly. As for “can they do it”: the nature of graduate research is long and winding, with results diffused across publications, papers, and dissertations. Thus, while assessment is a key consideration, given the complexity of the materials and subjects we teach, metrics for assessment in graduate populations may ultimately constitute very long-term and qualitative information. In the case of the Seminar, while we have provisional information as to its reception and success, it may be too early to understand the impact on its participants and facilitators. What does offer extensive insight, however, are participant-generated blog posts that reflect on the experience.

Conversation and Archival Encounter

While the success of these Seminars in terms of quality of conversation, depth of thought, and general demand and interest is due to a special alchemy of enthusiastic instructors, participants, and diverse expertise, I observed two fundamental pedagogical features within the structure of the Collaborative Research Seminar. These two features—conversation, and what I will term the “archival encounter”—challenge the general protocols of the reading room in ways that are productive for both participants and instructors. In doing so, they offer an opportunity to rethink what is in fact occurring when we teach with special collections or work with primary source materials.

“The archive” is often an archetype of rules, silence, and prowess—quiet rooms with careful pencils, researchers with well-formulated questions, librarians as gatekeepers to the treasures. Even with proper training on and permission to handle rare items, students may, as Patrick Williams (2018) notes, appear “almost scared to move” (118). We might consider this timidity as a result of the aura of the materials themselves, as Williams discusses, and also the imposing aura of the institution—including reading room, policies, and atmosphere. These archetypes (and indeed, stereotypes) obscure many of the realities of reading rooms, from the intellectual labor of staff to institutional hierarchies and pressures, and deserve to be thoroughly questioned (if not outright debunked). Thus, to encourage conversation around methods, to invite participants to encounter materials without research questions, context, or any hope of being an instant expert, is to de-center the authority of the reading room and reference model of special collections. This act not only demystifies, but also reimagines what parts of the archival encounter might be considered research: emotion alongside analysis, touch alongside historical knowing.

In their assessment of an undergraduate-based special collections program, Melissa Hubbard and Megan Lotts (2013) reiterate the importance of responsiveness and experience in their program’s success, encouraging students to relate materials to their “own thoughts and feelings” as a way to “view themselves not only as consumers of information, but also as interpreters and creators” (32). Hubbard and Lotts describe a relatively familiar process to those who have worked in special collections: the realization that authority and answers are not to be uncovered and “consum[ed],” but rather forged. Like the methods of Rancière’s Jacotot, the experience of encountering primary sources—especially during a class visit, in the context of a seminar, or in early stages of research—defies simple explication or understanding and instead asks for more of the researcher: thinking, feeling, creating context. As Patrick Williams (2016) notes, the general focus on explication, or the “supplying [of] answers” in response to materials, is often transformed when the reading room becomes a classroom space, “relieved by the overwhelming impulse to notice the odd or unexpected attributes of the materials with which we share space” (118). Williams’ word, “relieved,” is critical to the affective experience of this type of encounter—when we examine items that are not part of our fieldwork, that float without context for that initial moment of encounter, the experience of archival work is suddenly not about context or answers, but about immediacy. The moment of the encounter becomes a close orbit between the object and the ability to make sense of its form, our feeling.

This intensity of encounter often leads to imagination and identification as powerful forms of archival knowing, such as those described by Iris Cushing (2017), a participant in the first Seminar who returned to the Berg Collection to work on The Floating Bear, a rapidly and frequently published mimeograph newsletter edited by Diane di Prima and Amiri Baraka from 1961 to 1971. As part of her investigation, Cushing considers the question of context by examining the variety of authors represented in The Floating Bear, noting how the material document collapses the temporal distance between her and her subject, as well as creates a force-field of focus unto itself. Writing about these poets, she notes:

Those people are very close (their work is in my hands) and yet very far away (as it was made over half a century ago). In the Bear the names of the authors are placed after their work, so if I didn’t recognize the poem, I wouldn’t know who wrote it unless I turned a few pages. There’s no table of contents. The poem is the total focus of attention. I begin to read, my eyes wandering over the plain, uncluttered space of the page. (Cushing 2017)

While Cushing’s observations are specific to The Floating Bear’s decisions in layout and publishing, her statement that “the poem is the total focus of attention,” in the absence of paratextual information such as a table of contents, author biographies, or even secondary research in the moment of the encounter, might be a metaphor for the type of archival encounter that occurred in the Collaborative Research Seminar more generally. Cushing follows the imperative of the poem as “total focus of attention” as she states, “I begin to read,” offering a succinct methodology for archival work: find the focus in the material itself and encounter it on its own terms. Doing so, as she finds, leads to imaginative possibilities, generated by this specific materiality:

Sliding the very first issue of the Bear out of its white envelope, I found myself holding a stapled packet of 8 ½ x 11” pages, creased long ago from being folded in half for mailing. There was a purple 3-cent stamp in the top right corner, and a typed mailing label above the masthead, bearing the address of the poet John Wieners. Instantly I envisioned the young poet on a day 56 years ago, checking his mail, loosening the staple holding the newsletter closed (a staple now rusty with age) and sitting down to read it. (Cushing 2017)

Here, Cushing demonstrates not only the act of physically investigating the material for signs of its context—the fold in the paper, the stamp, the address—but also a key recipient, the poet John Wieners, wiggling the staple that holds the mimeographed pages closed. This act of imagination requires context—such as knowledge of Wieners’ status as a poet in the New American milieu, as well as the importance of The Floating Bear for creating poetic community when poets were far-flung, often broke, and hungry for each others’ work. However, as Cushing narrates, the act of sitting in a special collections reading room, imagining the addressee at a kitchen table, attests to the particular magic of primary source work—like crystals, these objects may hold energy of eras prior, memories, and experiences that we might tap into through imagination and experience. This collapse of boundaries is critical in the archival encounter, and the implementation of stations in the Collaborative Research Seminar intends to create space for these moments.

Writing on Valerie Solanas’s annotated SCUM Manifesto held in the Manuscripts Division, Collaborative Research Seminar participant Cory Tamler (2017) notes that

During the Collaborative Research Seminar we tried to think beyond the limitations of the practical and to imagine what might be possible within archives. I got fired up by instances of time leaving marks in an archive, on an object; an object’s temporal layers. What drew me to the annotated SCUM Manifesto is the way it contains two characters who are the same person. It’s a record of a conversation between the author and herself, but it’s a performative conversation, enacted for an audience (but what audience?) that was already historicizing her through public characterizations of her sexuality and mental health. It resists the freezing action of historicization, existing within time dynamically.

Together, conversation and “the encounter” in the Collaborative Research Seminar might echo Rancière’s (1987) idea of the material book as a site for “verification” based on its material qualities: “the materiality of each word, the curve of each sign” (15). When enmeshed as a pedagogical strategy, conversation and experience focus the instructors or facilitators not on verification of the student’s “knowledge, but the attention he gives to what he is doing and saying” (32). The second session is particularly instrumental for this process, since materials are presented as stations that participants can engage at will. Instructors may choose to circulate and linger around their favorite stations, sharing conversation with participants, or might abstain from revealing contextual details. The focus is not on transmitting knowledge, but on framing our experiences in terms of the material conditions that inspire them.

Conclusion

At its core, the move to create practical resources and theoretical constructs around the particulars of special collections pedagogy rests on a political and ethical imperative. The movement to reconsider radical, inclusive pedagogy and decenter the economic and cultural hierarchies that restrict access to education reminds us of important precedent for destabilizing the idea of who certain institutions are meant to serve. Libraries, from the nineteenth century onward, have served as symbols of democracy (even though they may be more accurately seen as testaments to benevolent capitalism)—the New York Public Library’s latest slogan is “Libraries are for Everyone,” and now, “Knowledge is Power.” At the same time, a public institution like the New York Public Library also contains reading rooms for rare books and archives, whose use is governed under significantly different conditions than the rest of the Library. While these practices are ultimately important for the safe preservation of materials, they nevertheless create mystique, and in some cases intimidation, for those who are not used to the rhythms of special collections—students who have not been told or taught that the materials of primary sources are theirs to examine, analyze, and place within history.

For instance, Cecilia Caballero’s (2017) “Mothering While Brown in White Spaces, Or, When I Took My Son to Octavia Butler’s Exhibit,” raised extensive conversation around institutional knowledge as a fundamental gatekeeping concern in primary source literacy, and in particular the political stakes of such uneven distribution of this knowledge. Caballero notes that while she applied to a fellowship to gain access to the Octavia Butler material at the Huntington Library, she took her unsuccessful application as an indication that she was not able to access the archive as a researcher and had to instead attend an exhibition of Butler’s work to examine it in person. While the Huntington Library, as well as many other major collections, permit researchers with a reference application alone, the fact that this only transparent to those already “in-the-know” poses a challenge to truly diversifying the researchers and research that occurs in special collections. Thus, to reconsider the role of special collections pedagogy as a fundamental act of access, and an act of making reading rooms more diverse and equitable, we must think critically about ways we might teach primary source research skills, including how to make meaning around objects, the institutions that hold them, and the community of people they engage.

As special collections continue to invest in digitization—whether that means making catalog records or finding aids available online, digitizing images of collection materials with accompanying metadata, or sharing born-digital materials in reading rooms and through online reference correspondence—we must consider how these materials are currently being used and also how they might possibly be used in the future. In determining the future of digitally-inflected archives and special collections, there is no substitute for conversations with the research populations we hope to serve and expand. To that end, the Seminar demonstrates through its teaching model, through student blogs, and through this very article, that the fundamental piece of context for primary materials is not necessarily secondary sources, nor is it an understanding of the differences between digital and analog archival objects. Rather, by understanding our embodied selves, we might collectively acknowledge the depth of knowledge that primary source practices afford.

It is my hope that the Collaborative Research Seminar might serve as an extensible and adaptable format for creating community and conversation between libraries and graduate institutions, as well as a model for an interactive approach to special collections pedagogy. While this collaborative model is an investment, for both institutions as participants, and requires extensive administrative support, as well as time spent teaching, coordinating student blogs, and following up with individual reference support, it nevertheless affords a starting point for thinking through specific practices of special collections pedagogy with graduate populations. In particular, it suggests that special collections pedagogy for graduate students is well-served by taking full advantage of methods that foreground conversation and experience, so that we might use interdisciplinary and multi-level classrooms as an occasion to listen closely to our primary sources and the ways they challenge institutional and disciplinary categories. In doing so, we will expand the possibilities of primary source work for our next generation of researchers, and welcome their fresh insights to conversations in higher education and cultural institutions alike.