Introduction

The idea of a Public and its influence on communication and civic activity has concerned rhetoricians since the Sophists sought to teach methods to persuade the city-state (polis). For the sophists, the Public’s common beliefs (doxa) and customary behaviors (nomoi) were the sources for content an orator must use to move the mob (Mendelson 2002, 4). According to Susan Jarratt (1991), the sophists were the first rhetoricians to concern themselves with what the Public considered to be valuable in social and civic spheres. In fact, many of their Public considerations are strong antecedents for modern ideas on social constructionism, community agency, and exigency as being located in social and civic situations. Ancient philosophers too sought to understand the Public by seeking to discover how best to convey truth to the masses. Most notably, Aristotle in Rhetoric envisions the usefulness of conceptualizing the Public to better address the intellectual needs of society through rhetoric. Thus, the work of defining the rhetorical Public began and this work continues to be of interest in communication.

From these classical beginnings in antiquity, the rhetorician’s domain has always been the “‘probable’” in “social and civic places … where reasoned judgments and policies are desirable” (Porrovecchio and Condit 2016, 195). In these arenas, the rhetor’s command of cultural understanding and the affinities of the Public become the most potent fodder for persuasion. The rhetor must identify the beliefs and values of the Public audience and they must create a space where the Public’s expectations are met, where they may play the roles they desire, and where they are afforded means to play those roles. And yet, though these insights remain true, the concept of a Public and how it must be considered for rhetorical engagement is changing. Hence, the purpose of this article is to address how the rhetorical Public is being redefined by attributes of digital spaces and online communications which blur the boundaries between private and public domains.

To begin, though modern rhetoricians still use beliefs and behaviors to inform persuasion as the sophists who preceded them, the Public they address now is much more involved and connected. Today, the Public participates in the creation of what is persuasive directly via instant communication platforms with speakers, user-centered design research for products, and real-time data collection occurring on their devices and in their homes that informs and shapes their day-to-day experiences. This level of Public engagement and interactivity is extending the Public sphere. Thus, Public integration into mainstream digital culture is reshaping the rhetorical concept of Public and, in order for the rhetorician to address said Public, it must be usably redefined.

The traditional definition of a Public, according to John Dewey (1927), is a group comprised of individuals that form an audience facing a similar problem, who recognize its existence, and then resolve to address it. While Dewey’s Public definition attended situations of its era and the time’s political spheres, it lacks today’s extended social spheres and the Public’s development of what Jenkins (2008) identifies as fragmented “knowledge cultures.” A knowledge culture is an organic assemblage of individuals into a group around a particular topic of interest. For example, members of the CBS show Survivor’s subreddit form a knowledge culture, a knowledgeable fragment of a larger reality show invested Public. These digital assemblages form around niche topics connected to the Public en masse who may be interested in superordinate categories, while also belonging to numerous, similar smaller groups.

Further, Dewey’s Public predates the idea that its members are co-participants in devising, shaping, and defining dominant parts of cultural and civic rhetorical exchange (i.e. communications, products, interface experiences, etc.). Since this Public reorientation has occurred, the Public has become a central focus in social communication contexts and a driving force for user-experience research. For example, companies like Facebook and Google conduct large scale Public data aggregation and analysis to make small, incremental changes to their media and algorithms to give users what they want and improve their experiences. Thus, today’s Publics provide a mainstream exigency for communication design work, evidenced by increasing user research interests in all realms of communication.

So, with the development of a 21st century participatory culture enabled by networked communication technology, the Public has evolved from targets of rhetoric into co-creators of social and civic discourse whose contributions matter and who feel responsible for being part of the public sphere (Jenkins, Purushotma, Weigel, Clinton, and Robison 2009, 6–7). As a direct result of the Public joining with the rhetor in the act of creating communication, designing user-experiences for heightened participation and engagement is a key focus of rhetorical research and praxis. Thereby, to support this key focus, the concept of “Public” is being changed in our culture to the degree that their experiences with communication steer its content and they have become integral to the core activity of creating rhetorical discourse.

Hereafter in this article, I begin by briefly illuminating the significance of the Public concept to rhetoric. Then, I go into the historical treatment of the term Public by offering Dewey’s definition. After which, I advance to Grunig’s situational theory of Publics that came out of the 1980’s. These two treatments of Public seem to dominate the philosophy of Publics in current social, academic, and civic areas. Moving from these historical concepts of Public, I discuss how the changing public sphere in response to the digital, knowledge cultures, participatory ideology, and end-user design interests are pressing the dominant Public concept to change away from those of Dewey and Grunig. Following from these pressures, I offer a newly redesigned concept of Public for rhetoricians and instruction. Last, I close with the implications of the new Public concept, the limitations of this scholarly endeavor, and a gesture toward research interests on Publics for the future.

The Power of Publics in Rhetoric

Throughout the history of rhetoric in social, academic and political spheres, the concept of the Public has played a significant role in rhetorical studies and practices. From Aristotle to Dewey (1927), Ede & Lunsford (1984) to Johnson (2004), and from Grunig & Hunt (1984) to Habermas (1991), rhetoric in all areas has relied upon a distinct interest in analyzing the Public in order to communicate persuasively. This above all is the chief concern framing the rhetorical act. The rhetor, to be successful, must be able to understand the needs, desires, and motivations of the Public audience to influence their attitudes and behavior (Locker and Kienzler 2015). For the ancients like Isocrates, so potent was the attention of the rhetorician to the Public that their craft (techné) was the only sure tool for motivating the masses to action for the good of the populace. To many communication scholars, this rhetorical attention to the Public remains the utmost concern.

Today, the importance of the Public to rhetoric in cultural and civic settings renders its consideration pivotal to the practice of our art in the social sphere. Communication and Public theory scholar Rosa Eberly (1999) states that “those who hold rhetoric as a productive as well as an analytical art need to keep searching for ways to reconceive of public discourse” (175). To do so, we must consider how we address, teach, and understand Publics and their importance to communication. Thus, redressing the term Public, in general, and adjusting its definition is an important consideration for maintaining effective rhetorical communication. So, to improve understanding of our Public concept, and to discover how best we might revise it, we must first address Dewey’s foundational definition, then Grunig’s past situational theory of Publics to understand their historical roles in cultural communication.

Defining the Historical Public Concept and Theory of Publics

To begin understanding the concept of a Public—to get at how it is conceived both pragmatically and theoretically—we must begin with Dewey (1927) and his definition of the term. Dewey, in The Public and Its Problems, comprehended the notion of a Public as being more than a population of individuals associated by common interest. Rather, he defined the Public as individuals arising and organizing in response to an issue. According to an interpretation by Eberly (1999), Dewey saw what he understood to be a Public as given and taking shape through communication. That is, only by acting rhetorically regarding an issue could a Public become self-identifying and definable. This rallying around an issue frames both Dewey’s and Grunig’s (1984) concept of a Public as formative, active, and reactive in terms of shared communication and associated action in the public space. So, it is from Dewey’s conceptual schema that James Grunig develops and posits a situational theory of Publics.

In Grunig’s (1984) situational theory of past Publics, he focused on the behavior of individuals and the actions that they take in groups to form what he recognizes as Publics. These Publics partake in communication (consuming and producing rhetoric), operate in the context of a situation, and do so in response to an issue or problem. Together, these communications, contexts, and issues form a Public’s stimuli. But, not all individuals in the social sphere (or Publics for that matter) have, recognize, or react in the same manner to any given stimulus. This insight prompted Grunig, in collaboration with Todd Hunt, to define four different types of Publics—nonpublics, latent Publics, aware Publics, and active Publics (Grunig and Hunt 1984, 22). For our purposes, nonpublics, or those not confronted by an issue, lie outside of the discourse setting, what we might think of as the rhetorical situation. Thus, from here forward, the theory’s discussion addresses only latent, aware, and active Publics and how they participate in defining the concept of a Public for our redesigning of the term.

Beginning with the formulation of latent, aware, and active Publics, they all come into existence in relation to a rhetorical situation. The three types of Publics are thus engrained in a setting where rhetoric “respond[s] to particular needs, of [the] particular publics, at [a] particular time” (Eberly 1999, 167). Hence, rhetoric acts upon these Publics in particular ways. For example, rhetoric on an issue may enable latent publics to become aware of a problem, aware publics may become active respondents to the problem, all while the rhetoric may be providing active publics material in the form of possible ideas and potential solutions so they may continue addressing an issue. Thus, latent, aware, and active publics act through and react to their rhetorical situation and respond to their perceived societal needs in that situation.

So, if we apply our knowledge about the concept of Publics—derived from Dewey’s definition and Gurnig and Hunt’s theory—to a situation within the realm of civic discourse, the civic rhetoric shaped and employed by an active Public connects the idea of communication by the public with the goals of the public (what Isocrates termed the Public good). Pragmatically speaking, the concept of a Public is defined by shared communication, identification, and resulting action, while theoretically, it exists situationally in relation to an issue or problem and is shaped by its activity, presumably aimed at service to or support for said Public. With this historical concept in mind, my discussion and analysis will now examine how four modern pressures may be redefining this concept of a rhetorical “Public,” and how these pressures create new rhetorical directions (and stimuli) for our consideration.

Four New Pressures Reshaping Publics

Moving from the analog era of Dewey and Grunig, today’s technologically mediated society opens-up individuals to experiencing a multitude of new communications, environments, and issues every day. Further, multiple forms of online networking allow for the new stimuli to convey and perpetuate beliefs and behaviors in a continuous stream. These techno-cultural changes are forcing the rhetorician’s Public concept, grounded in the definition and theory of Dewey and Grunig, to grow and adapt. The first pressure is that the public sphere where individuals have long participated in the exchange of opinions is extending into realms and communications once private. This is happening through new means of communication and data collection in the home and other once private environs that are now part of the digital public sphere. The second pressure is the formation of large, online knowledgeable communities who are exercising collective intuition and insight to produce more active Publics through increased reach, command of data, and access to information verses historically analog Publics. Also, developing in-kind with the wide dispersal of network communication technologies, the third pressure extends from participatory ideology that is influencing the populace by activating Publics to a degree that the traditional passivity of non-, latent, or aware Publics is being intrinsically counteracted. And, the last pressure comes from the centralization of Publics to the act of designing rhetorical communications via user-centered design and user-experience based interests. As a result, modern Publics and their expectations for discourse are more pronounced than ever before as they have come to see themselves as central to the rhetorical act. Hereafter, looking closely at these four pressures on the concept of a Public may provide us both an understanding of where each has come from and where they may be taking us as we move toward the future.

A Changing Public Sphere Changes the Public

Starting with the outgrowth of the public sphere brought into being by digital environments, we must consider how this change put pressure on the concept of a Public. The most contemporary concept of the public sphere comes to us from social philosopher Jürgen Habermas’ (1991) Structural Transformation in the Public Sphere. Drawing on language describing a public space occupied by individuals participating in discussions of informed, societal opinion in eighteenth century Germany, Habermas begins to articulate his social theory of the public sphere. To do so, he combines the observed German concept of social, rhetorical actions with Greek antecedents—“notions concerning what is ‘public’ … what is not” and the activities of discussion (lexis) and common action (praxis) in matters of the polis (3). To Habermas, the public sphere was a space where private citizens, literate in issues of civil society, come together to form a discursive Public separate from their private lives. This Public entered willingly into culturally open forums, wielded limited information ready-to-hand, and was motivated, often personally, by an issue or problem. However, this public sphere, distinctly owing to its analog origins, does not account for the changes of the digitizing Public and the deterioration of privacy. As communication and cultural experiences went online, Publics entered a digital space where they encountered information access that was far-reaching and beyond their singular knowledge; they came face to face with issues and problems of others which were readily thrust upon them; and, they were confronted with a space where their information was easily captured and made public.

According to law and privacy scholar Daniel Solove (2016) in “The Nothing-to-Hide Argument,” as individuals move online with their information, the divide between what is public and what is private blurs. What was once private information—our habits, interests, and ideas often explored from the comfort of our couch on a networked device—is data mined and collected as publicly discoverable, commercially purchasable information (Solove 2016, 737–40). This intrusion and publication challenges the traditional definition of the public sphere because an individual’s “own realm (idia),” the privacy of one’s own home (oikos), is compromised; the private becomes manifest in a public sphere even if the Public is ignorant about said sphere (Habermas 1991, 3). Additionally, the capturing of personal communications for public dispersal via technologically mediated conversations (those held outside of “the public life, bios politikos”) has eroded the private conversation to the point that all communication thusly mediated is potentially a public artifact (Habermas 1991, 3).

Therefore, these illustrations illuminate the extension of the public sphere into homes and into private conversations mediated by technology through the intrusion of the digital public sphere. As a result, the concept of the Public is reshaped by the cultural “nothing to hide” rhetoric in the public sphere itself. This transforms the fabric of what is Public in our concept. Also, as individuals forsake privacy for networking with the Public, more personal beliefs and attitudes enter into the sphere and weakens the Public as it becomes sometimes “less-literate” and more intimate and, at times, irrational. Hence, the changing public sphere altered by attributes of the digital sphere is fundamentally changing the Public to whom rhetoricians speak and must be accounted in our redesigning of the concept.

Forming Knowledge Cultures Influences the Public

Another digital change influencing the rhetorician’s Public concept is the formation of knowledge cultures in our techno-centric society. Knowledge cultures are communities where participants “share their knowledge and opinions” (Jenkins 2008, 26). These communities arise through audiences who organize themselves organically around specific interests or issues. Thus, by this definition and our understanding of how Publics form, it seems online knowledge cultures and Publics manifest in similar fashion, if not as one and the same. According to cultural theorist and media scholar Pierre Lévy, the knowledge culture serves as an “’invisible and intangible engine’” for what Jenkins calls the “mutual production and reciprocal exchange of knowledge” (quoted in Jenkins 2008, 27). Hence, it seems logical to assert that knowledge cultures may often be the foundation for a modern digital Public that is communing on a cultural or civic interest within an online, networked space.

However, if we compare the past analog Publics of Dewey and Grunig and Hunt’s to the digital ones of Jenkins and Lévy’s knowledge cultures, the difference is that the latter communities always have at their disposal the plethora of data online and the power of “collective intelligence” afforded by cyberspace (Jenkins 2008, 27). Collective intelligence stems from the idea that no single person can possibly know everything there is to know, but, collectively, individuals know things and have skills they can contribute to a shared pool of resources. This implies that every single person has valuable expertise to contribute and that by working together, the collective within a digital Public empowers the individual and vice versa. Additionally, Lévy argues that collective intelligence enables participants to become active collaborators in a knowledge community, which “allows them to exert a greater aggregative power in their negotiations” (quoted in Jenkins 2008, 27) because the knowledge community determines what is and is not knowledge.

Empowerment over knowledge in a knowledge culture may create situations where the digital Public grants itself power over what is good or effective communication with the digital Public sphere even if its membership lacks rhetorical expertise. Therefore, it seems knowledge cultures common to digital communities provide not only access to information, but access to shared intelligence and the power that the collective affords. Additionally, this increased power, alongside the valuing of all members may result in not only collective power over persuasive appeals (both cultural and civic), but also individual power as they feel emboldened by the strength of the collective intelligence of their community. For this reason, the new knowledge culture concept must be attended to by rhetoricians who address Publics. These new collective, knowledgeable, and active communities indicate that Publics are becoming more empowered, banding together, and participating in reshaping their own spaces, while also elevating their own status to that of an invaluable knowledge culture.

Participatory Ideology Shapes the Public

The next pressure on the concept of a Public as hinted at in my knowledge culture analysis is the new social push for participation in communication. This new participatory ideology is due to the empowered status of the Public and its membership in the current digital, networked Public sphere. This ideology has activated Publics far beyond the traditional means of those found in Dewey’s non-networked, analog settings of the past by connecting today’s member of a Public with encouraging and supportive (inter)actions. Just as rhetoricians must consider the influences of active knowledge cultures for strong social and civic discourse, we must attend to the participatory ideology these cultures represent and their effects on modern Publics.

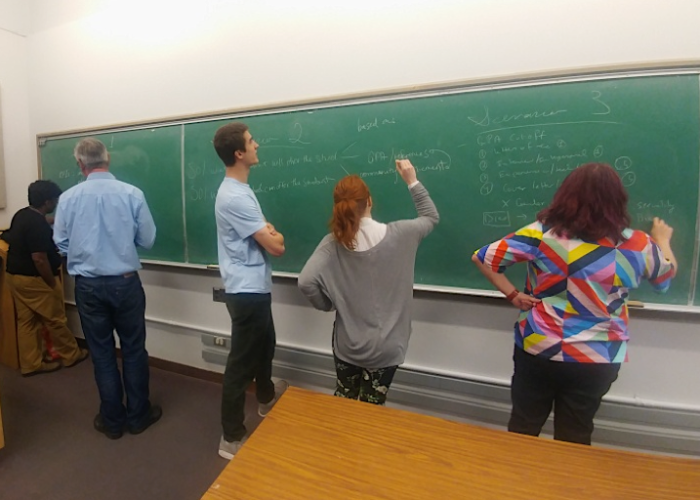

According to Jenkins et al. (2009), today’s hyper-active Public is engaged with the creation and sharing of cultural knowledge through media. This position of power in relation to communicating knowledge makes participants feel central and indispensable to public rhetorical acts. Also, Jenkins (2008) indicates that a participatory Public conflates “media producers and consumers” into a single role, participants (3). As participants, all individuals have agency and interact with one another according to the new cultural perception that everyone in an audience is always-already involved in meaning-making by degrees. This view of participants connects to the idea that a Public in civic discourse may be perceived as an “involved audience” (Johnson 2004, 93). According to Robert Johnson (2004), “the involved audience is an actual participant in the writing process who creates knowledge and determines much of the content of the discourse” (93). Thus, an inclusive, generative view of today’s Public arises from participatory ideology and modern audience theorizing. Just as in knowledge cultures where individuals are central to creating and communicating, participatory ideology posits that everyone has valuable expertise and are expected to be actively collaborating in Public discourse as participants. Therefore, as rhetoricians, our understanding of the Public concept must admit the reshaping induced by current participatory ideology and redesign the term accordingly.

User-based Design Expectations Inform the Public

Our final pressure reshaping the rhetorician’s Public concept is wrought by our own growing interest in user-based design for communication purposes from user-experience research (Hoekman Jr. 2016). By focusing our efforts on designing documents for end-users, we are priming audiences to expect communications to conform to their desires. As such, the employment of design practices in many modes of digital public discourse may have already begun to alter expectations toward more personalized experiences. For example, Steve Krug (2014), an expert web designer and advocate for user-experience design, posits that the fundamental conventions of webpages and how they communicate is rooted in not only being intuitive, but also in recreating positive experiences that are desirable for individual users. Thus, rhetoricians must be attuned to the effects of user expectations when communicating with modern Publics in the digital age. Reorienting communication in this manner requires that today’s rhetor consider how user-based document design effects the Public and its concept of effective communication in light of expectations generated within the digital public sphere.

To begin the reorientation, the rhetorician may start from the concept of document design. Document design refers to how communicators assemble documents to create an agreeable, useful experience for the audience. According to Karen Schriver (1997), communication scholars need to persuade an audience by discovering and attending to a “reader’s needs” by appealing to their “goals and values” through design elements (11). While this represents an approach to communication familiar to rhetoricians addressing rhetorical situations, the modern audience in the public sphere may come to expect civic communications to mirror their expectations, perhaps even to put their own opinions first and foremost (i.e. consider the social media echo chamber). In other words, the Public may see itself as the most important part of the rhetorical situation and devalue the message and/or purpose of the communication because of their perceived “elevated status” as a focal point of design. In this situation, if the digital Public sees a communication as ignoring its authority, power, or import, it may, according to Dentzel (2013), disregard or even attack a communication for its apparent inattention to the Public’s interests. It is the elevated status of the Public developed by user-based design practices and changing digital communication environments that rhetoricians must be most aware of as they take-part in developing social and civic discourse.

Furthermore, the modern networked audience expects their experience with a communication to be informed by a vested interest in what they want and what they believe is best for the Public to which they belong. Thus, in the user-based approach to communication design, the Public expects rhetoric to seek to not only meet their individual expectations, but also to be democratized to promote inclusion and well-being of the Public (Dentzel 2013). All the while, as alluded to previously, users of modern communications expect interaction and for it to be easy. They expect to contribute and they expect to be a valuable part of a communication once they participate (Jenkins et al. 2009, 6–7). It seems we as rhetors today have a difficult challenge before us. Thus, user-experience design expectations are redesigning our rhetorical discourse and reforming the concept of the Public itself. As contemporary rhetoricians, we must reshape our concept of a Public to include how its expectations are informed by the practice of user-based design and networking as well as the other pressures previously discussed.

Reconceptualizing the Rhetorician’s Public

Based on the initial definition and theory of a Public and the preceding examination moving from the concept’s past to present day pressures, a newly redesigned concept of the term emerges. Extending beyond the traditional definition, rhetors must attend to several new aspects of Publics as they prepare discourse for the public sphere. First, they must attend to Publics as being both personally, as well as publicly, invested in the rhetorical situation. As the public sphere has enveloped more aspects of the private sphere due to the digital, Publics have formed more intimate connections between the discourse and their identity. Second, our concept must acknowledge digital Publics as potentially less objective, but more prone to wielding personal expertise and powerful collective intelligence drawn from online communities and from vast stores of networked cultural information that are immediately available to them. Last, rhetors must employ a Public concept wherein Publics see themselves as central, generative contributors to democratized communications. That is, our concept of the Public needs to acknowledge the desire of individuals not only to be included, but also valued by a clear and vested interest in their contributions, concerns, and experiences. These aspects of the rhetor’s redesigned concept of a rhetorical Public must be considered to affect social and civic audiences successfully in the contemporary cultural environment surrounding discourse in the digital age.

Closing Remarks on Reshaping the Rhetorical Public

Though it is impossible to have the definitive and final word on a concept so rich and varied as the rhetorical Public, observations concerning its definition and theory in this scholarship are noteworthy. They begin to direct our research and suggest future redesign work for this and other terminology central to the shared disciplines in the fields of English, Communication, Technology, and Design. First, though the Public is still defined by shared communication and action as Dewey articulated, those traits have taken on new depth as members infuse their daily lives with a more personal relationship to Publics and more shared opinions are taken up to inform the digital public sphere. From this realization, I caution that our Public, in theory, may feel differences of opinion as attacks on themselves or their identity.

A second observation is that while Grunig and Hunt’s situational theory of Publics is accurate in its assessment of Publics as existing situationally, their theory could not have predicted the inward articulation of today’s Publics. That is, our more self-interested and self-centric Publics may see themselves as the most important part of a situation, and therefore they may see themselves as the locus for its creation. This may result in forsaking messages and purposes in the discourse that do not focus on “me.” Again, in light of this finding, I warn that a new Public may seek out echo chambers that reflect their ideas back to them out of overemphasized self-importance. Additionally, this new conceptual Public may be easily alienated by social or civic discourse that fails to replicate the collective knowledge of the fragmented groups to which they belong. But, in any event, how rhetoricians need to respond to this reconceptualization of the Public is beyond the scope of this scholarship which is geared toward redesigning the concept of a Public and pointing toward some of the needs we must consider prior to teaching it.

So, in closing, for the concept of a Public and how this scholarship has endeavored to encourage its exploration and consideration, there is much more work to do. This is especially true regarding how we teach rhetoric to respond to the Public as it changes. Though this article has begun to consider some of the changes of social spheres—the influences of knowledge cultures, the reshaping of participatory ideology, and the informing of user-based design—there remain clear lines to be drawn showing how exactly these considerations align and derive from how we teach the dominant definitions and theories of Publics posited by Dewey, Habermas, Grunig and Hunt, and others. To undertake that exploration, I leave it to the next rhetor who picks up where the sophists left-off, ponders Dewey, study’s Grunig, Hunt, Habermas, Jenkins, and others empirically to discover where our definition and theory of Publics is heading next and how we need to conceive it for continued successful social and civic discourse.