Edwin Mayorga

Swarthmore College

Abstract

The Education in our Barrios project, or #BarrioEdProj, is a digital critical participatory action research (D+CPAR) project that examines the interconnected remaking of public education and a New York City Latino core community in an era of racial capitalism. This article is a meditation on the ongoing development of #BarrioEdProj as an example of strategically coupling digital media with the theories and practices of critical participatory action research (CPAR). The author describes the project and the theoretical and political commitments that frame this project as a form of public and participatory science. The author then discusses some of the lessons that have been learned as the research group implemented the project and decided to move to a digital archiving model when our digital media design was initially ineffective. The author argues that rather than dropping digital media, engaged scholars must continue to explore the potentially transformative work that can come from carefully devised D+CPAR.

Introduction

The co-researchers of the Education in our Barrios Project (#BarrioEdProj) and I had spent seven months reflecting on how to expand our social media reach in East Harlem when Mariely said, “Edwin, this whole technology thing doesn’t work in El Barrio.” Mariely’s comment made explicit a set of concerns I had been contemplating for some time, namely, that trying to politically and intellectually engage the community through digital social media was not going to effectively encourage participation, or the development of more connections to local history, or a discussion of relevant educational and social issues. If digital media was not working in El Barrio, as Mariely suggested, I wondered if we should drop digital tools from a project primarily concerned with collaboratively documenting the interconnected remaking of public education and Latino core communities in an era of racial capitalism altogether (Melamed 2011). Ultimately, we chose not to drop social media from the project and instead to critically and continuously question why, when, and how we want to integrate it into participatory and community-based research.

This paper asks, What can we learn from integrating digital tools and social media platforms into critical participatory action research (CPAR) projects? Drawing on project field notes that were collected between June and December of 2013, I trace the evolution of #BarrioEdProj to cull lessons for “engaged” or activist scholars doing public science work in our digital age (Hale 2008). I begin by giving some background on the project and our research site, East Harlem and its schools. I provide an overview of the project’s design and highlight some theoretical underpinnings of what I describe as digital critical participatory action research (D+CPAR). Then I discuss how we grappled with the realization that the social media aspect of our project was not working in El Barrio.

In the months that followed Mariely’s comment, we would rework our research design in a way that centered digital, participatory archiving as part of our D+CPAR design (Caswell 2014). This reworking was guided by giving regular attention to how our varied uses of social media shaped our collective approach to research, teaching, and learning for social justice. Our social media aims were twofold: we wanted to deepen and solidify our engagement with people in East Harlem (El Barrio), and we wanted encourage more public engagement among people in East Harlem and across New York City.

I describe this evolution of #BarrioEdProj and discuss some of the lessons we learned from navigating this change. The challenges we faced made it clear that the traditional challenges ethnographers face, both in gaining community entry and building trusting relationships, remain issues in digital social science (DSS). We also learned that embracing digital media presents new perspectives and new questions for the researcher. Questions of digital access, infrastructure, and practices of participation, for example, are important considerations that engaged scholars must interrogate as part of their work. I conclude by arguing that #BarrioEdProj should remind researchers that the “universal digital turn” amplified the terrain for intellectual and political struggle, where inequity is reproduced, and transformative public science can be born nyc.

Background

I am an educator-scholar-activist-of-Color who has labored, and fought, for educational and social justice before, during, and after the 12 years that New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg managed the city and controlled the public school system (Suzuki and Mayorga 2014). I locate my scholarship at the intersection of critical education studies, cultural political economy, critical theories of race, digital social science, and social movement theory. It is my view that activist research plays an important role in making transparent the circulation and material effects of the period of racial capitalism in which we live (Melamed 2011; Robinson 1983). Following Melamed (2011), I argue that this state-driven, racio-economic partnership adapts and revises white supremacy and capitalism in order to maintain dominance. In these circumstances, my research program and conceptual frameworks aim to trace the contours of structural oppression and histories of resistance through participatory and digital methods in order to foster social justice (Anyon 2009). In #BarrioEdProj, my primary concern is the relationship between the cultural political economy and neighborhoods, communities, and schools—what I describe as the school-community nexus. The nexus is a frame for thinking about the shifting, discursive, and material linkages between what happens in and around schools and larger society.

I think about the school-community nexus across New York City neighborhoods, but I pay particular attention to what Ed Morales described as Latino core communities and their local schools (Morales forthcoming). Initially majority-Puerto Rican, the New York City Latino population has rapidly increased and diversified since the late 1960s. During the twentieth century, certain neighborhoods, like East Harlem, Williamsburg, the Lower East Side, the South Bronx, and Washington Heights, would become cultural, political, and economic, hubs for Latinos. These neighborhoods would experience waves of extreme economic hardships, political strife, urban renewal, displacement, and vibrant social life. My work is focused on exploring the reformation of these core communities in relation to struggles within education.

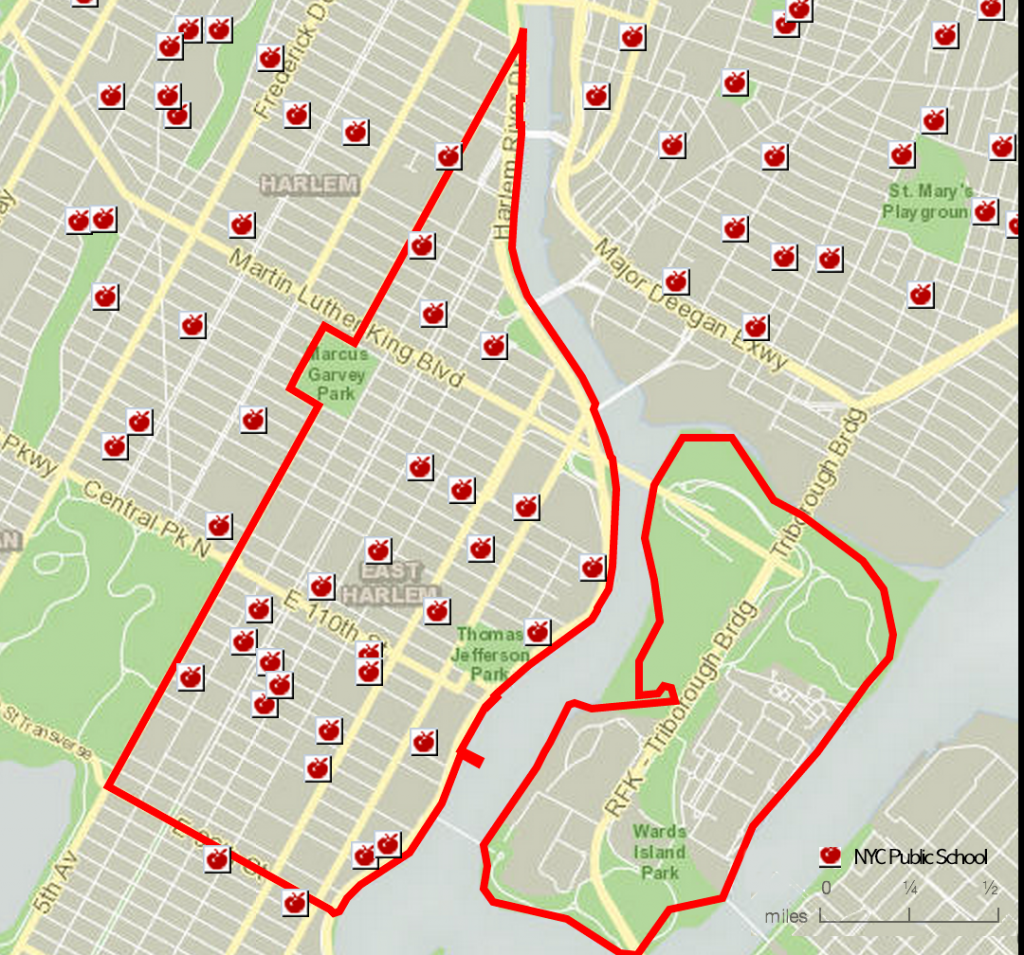

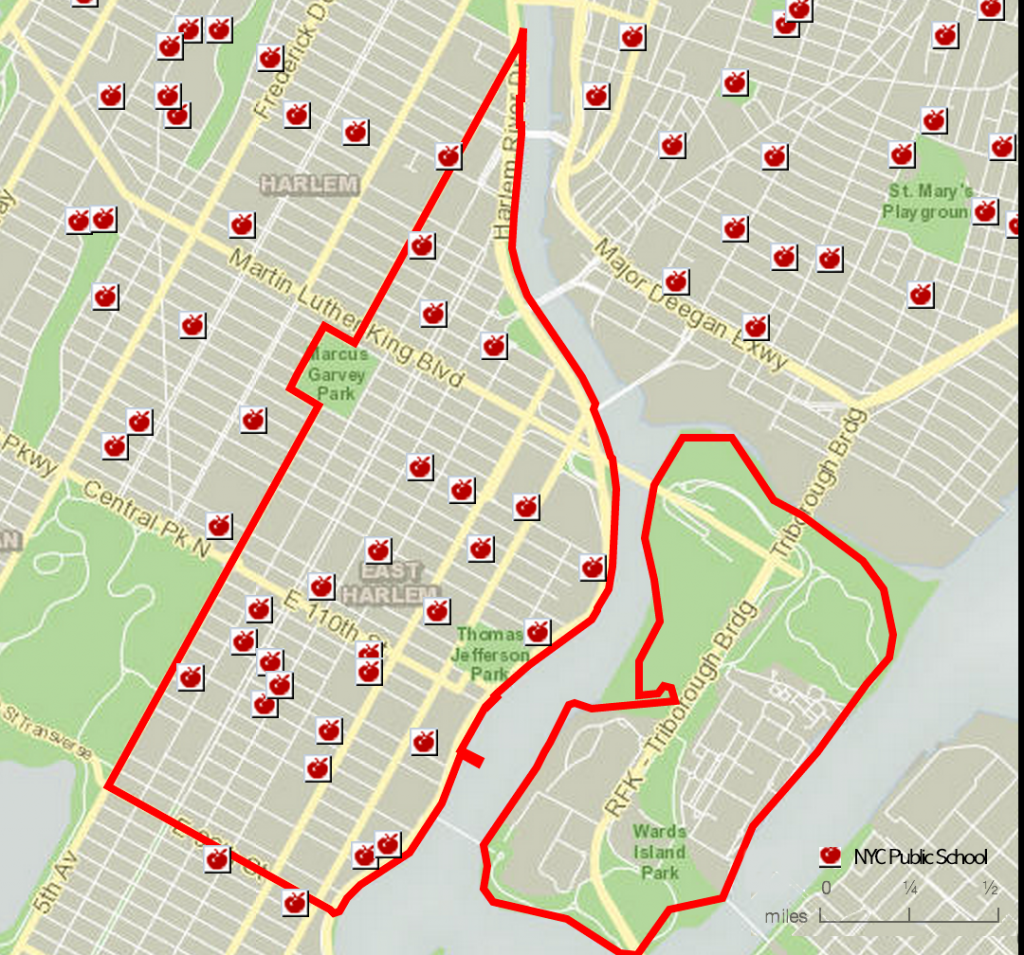

While Latinos have been a major voice in struggles over public education since the early twentieth century, only certain aspects of the Latino education story, like bilingual education, have received significant attention. Recently, Latinos became the largest population of students in the public school system (NYC IBO 2013); nationally, there has been increased concern over a “Latino education crisis” (Gándara and Contreras 2009). It was in working through the convergence of community and educational crisis that I opted to look at the Latino core community of East Harlem (El Barrio) as a window into racial capitalism, its circulation, and its effects. A map of the distribution of public schools in East Harlem is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Map of East Harlem and East Harlem Schools, Image created with http://maps.nyc.gov/, #BarrioEdProj collection.

Figure 1. Map of East Harlem and East Harlem Schools, Image created with http://maps.nyc.gov/, #BarrioEdProj collection.

East Harlem and its Public Schools

Once a home to Italian and Eastern-European Jewish immigrants, East Harlem would become a Puerto Rican stronghold following en masse migration to the US mainland between the 1930s and 1970s. Over the course of the twentieth century, the Black (non-Latino) community would also make up a large portion of East Harlem (Dávila 2004). Since the 1960s, when US immigration laws opened the door to more Asian, Latino and Middle Eastern immigrants, the diversity of Latinos moving into different parts of New York broadened and complicated Latinidad (Latinoness) in New York City and East Harlem (Dávila 2004; Flores 1997). In the midst of demographic change, East Harlem would become a symbol of urban poverty and a site of political struggle , as people dealt with varying cycles of organized abandonment and urban renewal (Freidenberg 1995). More recently, East Harlem has experienced change through a rise in luxury housing over affordable housing, a cultural rebranding of the neighborhoods as Upper Yorkville or SpaHa (Spanish Harlem), and an increasing displacement and departure of long-time residents (Dávila 2004; Morales and Rivera 2009; Padilla 2012).

As East Harlem has undergone economic and social change, the city and East Harlem’s public school system has also experienced significant and often difficult change. Change in the schools has often revolved around governance and the voice of the citizenry in the education of youth. Between the early 1900s and the 1960s, the schools were operated through a highly centralized bureaucracy. During those decades, East Harlem was known as an area with some of the worst performing schools in the city (Fliegel and MacGuire 1993; Nieto 2000). The tumultuous struggle for community control of schools–the struggle in the Ocean Hill-Brownsville (Brooklyn, NY) is the most widely recalled example of this larger phenomena–would be ended by the implementation of a decentralized governance formation that dispersed bureaucracy and gave families limited but varied forms of choice between 1970 and 2002. During decentralization, East Harlem launched bilingual education programs and a “progressive” small schools movement that would have a profound effect on East Harlem education (Fliegel and MacGuire 1993; Meier 1995; Pedraza 1997). Then in 2002, Mayor Michael Bloomberg re-centralized the system as a Department of Education rather than a Board of Education, a governance reorganization that, critical scholars have argued, is part of a broader, neoliberal assault on public education (Buras 2011; Lipman and Hursh 2007; Lipman 2011).

The #BarrioEdProj

#BarrioEdProj is comprised of a trio of co-researchers that includes two young Latina women from East Harlem: Mariely, age 19, and Honory, age 23. With funding provided by the CUNY Graduate Center’s Digital Initiatives grants program, Mariely and Honory were hired as co-researchers to help develop and steer the project (the research team is shown in Figure 2). We met, and continue to meet, three to four times a month to discuss readings about East Harlem, education reform, and qualitative research methods; participate in digital media and research trainings; analyze collected data; construct our website; and plan next tasks. Together we have conducted interviews, observed public meetings, and conducted archival research. Data analysis has primarily involved thematic analyses of transcripts, observations, archival data, and online dialogue (Boyatzis 1998).

Figure 2. #BarrioEdProj research group (and son), Photo by http://www.sindayiganza.com/

Figure 2. #BarrioEdProj research group (and son), Photo by http://www.sindayiganza.com/

Because this was a place-based project, we focused our attention on connecting with the neighborhood through in-person and online outreach to individuals and organizations from East Harlem and East Harlem schools. The outreach was geared toward raising awareness about the project, identifying potential interviewees, and building relationships where we would offer to promote events and make note of issues that were of concern to these individuals and organizations. The local Community Board (CB11) has been extremely supportive and has provided space to conduct interviews. In addition, East Harlem Preservation, a volunteer advocacy group dedicated to promoting and preserving the vibrant history of East Harlem, has endorsed the project and shares relevant information and events with #BarrioEdProj on an ongoing basis. The Community School District (CSD 4) offices and the local Community Education Council (CEC) are two other key entities we have developed relationships with over the life of the project.

In June of 2013 we launched http://barrioedproj.org (WordPress site via OpenCUNY.org) to serve as an information clearinghouse and interactive space for discussion. At the moment, the website uses a language translation plug-in to offer content in Spanish and English, but a companion site, solely in Spanish, is a being explored as a possibility. The bulk of the digital data thus far comes from digitally recorded, semi-structured video interviews, with a multi-generational, bilingual (English/Spanish) group of stakeholders connected to East Harlem education. Interviewers asked interviewees about their relationship to East Harlem and its schools, their perspectives on cultural and economic change in the neighborhood and the schools, and, finally, their views on the future of the neighborhood and the schools. Excerpts of interviews were edited, produced, and then embedded on the website, where viewers can make comments. In addition to the interview segments, we are continuing to collect images of East Harlem via Flickr and Instagram, scan archival material and self-created informational maps, and collect music produced by East Harlem groups. All this material will eventually be placed on the site.

We also used the voice journalism tool Vojo.co. Based on the Drupal-based VozMob, Vojo is a multilingual tool that allows participants to share stories through voice messages, texts (SMS), and images (MMS). Vojo was the tool used by the creators of the award-winning participatory documentary Sandy Storyline. For #BarrioEdProj, Vojo provided a bilingual venue for individuals who wished to remain more anonymous than video interviewees to share their views. This included teachers and families who have a more critical stance in the educational system but who also did not want to make themselves vulnerable to losing their jobs for speaking out. Vojo was also used as a way to conduct interviews at events when the video camera seemed more invasive for prospective interviewees. Like the interviews, Vojo entries are edited and produced through CowBird and then posted on the website for public commentary.

In addition to interviews and Vojo entries, relevant readings and resources about education and gentrification were posted on the website, our Facebook page, and our Twitter account (@barrioedproj). Resources included a “tips sheet” about getting into college and a blog post with different financial resources to pay for college. Finally, RebelMouse, a social media tool that brings together various social media feeds from many social media platforms, was also embedded on the website.

Literature

Critical, Participatory Action Research (CPAR)

D+CPAR is an attempt to begin defining a strand of the still-nascent field of Digital Social Science, where digital media and social media are integrated into critical participatory action research (CPAR).

CPAR is both a way of knowing and fertile ground for generating ways to contest inequity. Torre et al. (2012) write, “Rooted in notions of democracy and social justice and drawing on critical theory (feminist, critical race, queer, disability, neo-Marxist, indigenous, and poststructural), critical PAR is an epistemology that engages research design, methods, analyses, and products through a lens of democratic participation” (171). CPAR places the processes of problem posing, research, analysis, and data sharing in the interlocking hands of adults and youth, the focus community, and partnering scholars and activists. While CPAR projects develop their own structures depending on the needs and capacities of participants, there is a commitment to contesting traditional “asymmetrical relationships” in which scholars are seen as experts and those outside of the academy are framed as lacking knowledge and thus incapable of meaningfully participating in research (Young 1997). Instead, CPAR projects are premised on collaborative practices where the voices of all participants are equally valued in decision-making and research work. As such, a democratic thread runs through all aspects of the research process.

Guided by democratic principles, CPAR work goes further by asking, Research to what end? In the 1960s and 1970s, strands of participatory and action research were conceived by activists and engaged scholars “to systematize and amplify local knowledge” in order to transform “it into social activist movements that contested the power of elites and struggled for greater socioeconomic justice” (Lykes and Mallona 2008, 109). While PAR and CPAR have evolved over time, the commitment to facilitating people’s movement from inquiry to social action remains a key component. As Torre et al. (2012) note, “critical participatory projects are crafted toward impact validity, anticipating from the start how to produce evidence that can be mobilized for change” (181). As projects that are driven by the interests and knowledge of local people, the research process is designed to inform and inspire social action. Gathered evidence can be mobilized for change in a number of ways, including the presentation of participant-generated reports (Watters and Comeau 2010), data performances (POLLING FOR JUSTICE Part 1 of 3 2010), and speeches at governance body meetings (Torre et al. 2012). Each of these forms of evidence-sharing scale-up local knowledge as a means to engaging a broader public and working toward justice.

It is the democratic spirit of CPAR and the commitment to using evidence as a mobilizing tool for change that motivated me to use CPAR as a framework for the #BarrioEdProj. This turn would soon cross with my contemplations of digital social science research.

Digital Social Science (DSS)

Without overstating it, digital humanities as a field has gained traction (Spiro 2014; Terras, Nyhan, and Vanhoutte 2013), whereas DSS is only beginning to emerge (Spiro 2014). The Economic and Social Research Council (n.d.), a British organization, defines DSS as:

the application of a new generation of distributed, digital technologies to social science research problems. The aim is to enable social research by developing innovative and more powerful, networked and interoperable research tools and services that make it easier for social scientists to discover, access and analyse data, and to collaborate so that they may tackle increasingly complex research challenges.

And Spiro (2014) adds that DSS:

encompasses both quantitative and qualitative approaches; it involves new data sources (such as social networking data), methods (such as social network analysis), capability (such as collaboration tools), scholarly practices (such as new publishing models), areas of study (such as Internet studies), and scale (such as global collaborations).

DSS is very wide open and, as such, integrating DSS concepts and tools into critical participatory projects is an opportunity for engaged scholars to “make the road while walking” (Horton et al. 1990). It is important to note that scholarship in interdisciplinary areas like Community Informatics (CI) and Participatory Design Action Research (PDAR) can potentially fall under the umbrella of DSS (Carroll and Rosson 2007; Gurstein 2000). With respect to #BarrioEdProj, CI’s commitment to the application of information and communications technology (ICT) and PDAR’s exploration of Action Research (AR) are of particular relevance (Gurstein 2007). With that said, our project began by looking at literature on digital ethnography for the design of #BarrioEdProj as a DSS project. As such, I focus on digital ethnography in this paper as a way to think about creating new data sources, new ways to present data stories.

For social scientists like Underberg and Zorn (2013) and Murthy (2008), digital ethnography is, like traditional ethnography, about gathering, sharing, and analyzing stories. The availability of digital video cameras and digital voice recording tools, along with online data storage (Cloud) and online video tools (Vimeo/YouTube), can potentially reshape how ethnographic stories are collected, analyzed, and shared. Being able to store digital video in a cloud, for example, can allow research groups to look through data on our own time in our own location. If research groups have already viewed this data, then face-to-face research meetings can focus on collective analysis or other relevant activity. Moreover, stored data can “be re-analyzed, examined for inter-coder reliability and retrieved by future generations of researchers” (Shrum et al. 2005). Of course, this is not all new. What is new, or perhaps not something not sufficiently embraced by researchers, is the opportunity to provide more continuous data sharing with a broader public.

Additionally, these tools make it possible to share data over the course of project implementation or at the end of a study. Researchers can thus make strategic decisions about when, why, and how, data can be made public. The Morris Justice Project (MJP), for example, was a critical participatory project in the Morris Avenue section of the Bronx. MJP participants documented community member experiences with the police through a survey of over 1000 people. After the survey was completed and studied, the group collaborated with the Illuminator—a cargo van equipped with video and audio projection tools, born out of the Occupy Wall Street movement— to share data on an open wall of a Morris-area apartment building. This digital data share served as an open letter to the NYPD and as a space for community discussion and data analysis.

Similarly, the #BarrioEdProj website was conceived as an open wall where data would be shared and conversations could be had among site users. Through Vimeo, #BarrioEdProj made interviews segments and video coverage of public events available to the public on an ongoing basis. Public engagement with the data online provides another source of data concerning digital participation practices that can be examined at a later point.

In both MJP and #BarrioEdProj, there is a curatorial dimension as stories are told and re-told differently through the selective presentation of data. Using hashtags on a website allows researchers to connect different data pieces across multiple themes. In our case, interviews that discussed education history in East Harlem could be tagged as education governance (#EdGov) and education history (#EdHistory). The segment would then be available through different streams on the website depending on what users were interested in exploring. For researchers, tagging data can also mirror traditional forms of coding qualitative data in thematic analysis (Boyatzis 1998, Braun & Clarke 2006), as data with the same tag can be seen collectively and then analyzed. Finally, digital tools like RebelMouse allow researchers to gather posts from across the various social media tools being used through hashtags. Once the posts have been collected, RebelMouse users can then move them around to emphasize certain posts over others. In each example, researchers are able to exercise curatorial powers over how data is organized and made available, leaving platform users with various trails of crumbs to follow and jump between.

There are many more ways to think about the merging of digital social science and critical participatory research projects, but I want to briefly move to public engagement as a part of the D+CPAR process and as an object of study.

Public Engagement

Using a D+CPAR framework, we considered how digital environments and social media could contribute to creating more equitable spaces for public engagement. It is clear that “’everyday life’ has become increasingly technologically mediated” (Murthy 2008), making it “difficult to distinguish between digital and non-digital activities” (Leonard & Losse 2014). Public engagement in the digital age is a concern to researchers, marketers, and political advocates, to name a few. Research on practices among internet users looks at a number of different areas, including political activity, personal interests, and social uses (Smith 2011). Our working notion of public engagement is grounded in education studies and political advocacy.

Orr and Rogers (2011) argue that “[p]ublic engagement cannot be reduced to individual acts such as voting, speaking with a teacher, or choosing a school. Public engagement emerges as parents, community members, and youth identify common education problems and work together to address them” (xiii). Historically, education has been a key site for political struggle in the U.S., and it has been particularly important for marginalized communities. In some instances, engagement in school politics has meant opportunities for exerting voice and demanding concessions from the state. At other times, the elimination or curbing of engagement has been part of maintaining control and inequity. Today, the voices of members of US society are heard unequally, as “[t]he privileged participate more than others and are increasingly well organized to press their demands on government” (Orr & Rogers 2011, 2). In light of this, we contemplated how #BarrioEdProj could provide spaces for various stakeholders concerned about education to come together through the Internet and social media.

For researchers, creating spaces for engagement can take many directions, but for #BarrioEdProj the focus remained primarily on creating opportunities for individuals to interact and using social media to share information relevant to the community. With our website and social media platforms, the underlying idea was to invite people to view collected material and then have them respond to the material and the comments of other participants. Recent studies note that approximately 60% of American adults use social media, and 66% of social media users — or 42% of all American adults — use social media for some form of political engagement (Rainie 2012). Taking this statistic into consideration, the digital holds promise as a site for political work, though it should not be considered a panacea by any stretch. In having digital participants engage one another through #BarrioEdProj sites, the idea was to identify key educational problems that could be addressed collectively through continued dialogue and action planning.

While the use of the Internet and social media in research has many promising aspects to it, including democratizing communication, expanding opportunities for public engagement, and expanding networks of relations, it cannot go un-critiqued. First, membership in social media communities are “inherently restricted to the digital ‘haves’ (or at least those with digital social capital) rather than the ‘have nots’” (Murthy 2008, 845). This is both a cultural and material problem that emerges in “societies structured in dominance” (Hall 1980, 320). Public engagement is increasingly contingent on digital infrastructure (access to Wifi, broadband quality, etc.) and digital savvy (Prensky n.d.). As I discuss later, infrastructure and the digital practices of our participants were key issues that would inform the redirection of #BarrioEdProj.

A second point to consider is the way that capital and digital participation are deeply entangled. In a recent article in Dissent, Jung (2014) compares Tronti’s theory of the “social factory” to social relationships in the Web 2.0 age. The “social factory,” according to Tronti (as discussed in Jung 2014), is where “every social relation is subsumed under capital and the distinction between society and factory collapses, so that society becomes a factory and social relations directly become relations of production” (48). Jung argues that the social, playful labor of participation in Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and other social media platforms is tracked and farmed as a new source of value extraction and accumulation of capital—relationships are thus commodified. Around 70% of the social media market is dominated by Facebook (Jung 2014). Users of Facebook and Instagram are high frequency users, checking their sites at least once daily (Jung 2014). These realities present engaged researchers with an ethical dilemma in which one must consider whether one’s use of digital technologies is merely contributing to commodification and the reproduction of social inequities. Open source tools like elgg and Dolphin provide ways to create social networking alternatives to the proprietary platforms, but the comparatively limited reach of these platforms can make them difficult for participatory research projects that seek to be far-reaching and accessible. In the end, #BarrioEdProj proceeded with proprietary platforms (with the exceptions of WordPress and Vojo) because we felt that East Harlem’s public institutions did not have a strong digital presence in the community. I go into more details about the digital landscape of East Harlem in the next section.

Results & Analysis: Lessons from #BarrioEdProj

Evaluating #BarrioEdProj

Evaluating the effectiveness of a D+CPAR project involves looking at both academic impact and external, or public, impact (see JustPublics@365 and the London School of Economics and Political Science for more). We understood impact in this context as referring to our ability to create public engagement opportunities that would be used by a growing number of people. One way we can look at impact through social media is by “measuring links, downloads, views, usage, and re-mixes” (JustPublics@365 2013). We found limited success in attracting people to create and engage a public through the digital environments we offered. According to our WordPress analytic tool (Jetpack), we had received around 828 visitors between June and December of 2013. Looking at both the number of “likes” and “reach” on Facebook, we found that during this period we had very few people (28) “like” our page, and our outreach was equally modest, averaging around 15 to 20 people being reached organically (The project has never paid for advertising on Facebook or any other proprietary platform). On Twitter we had 110 followers and had a reach of about 1,000 people a month (according to SumAll). These initial bits of data showed us that Mariely was right in suggesting that our social media was not working in East Harlem. We began to ask, Why not?

We think that there were a number of reasons our digital participation work was failing to take hold in East Harlem. Some the problems were internal issues that we could change, while others were more external issues that require further research to verify. I will briefly highlight three potential issues.

First, trying to build on-the-ground connections at the same time that we were trying to launch the social media work was a major misstep. Establishing a strong digital presence in D+CPAR work requires strong “community anchors.” Like traditional ethnographies, DSS researchers need to develop trusting relationships with community organizations and individual advocates. Having established the majority of our on-the-ground relationships a few months prior to the launch, we lacked sufficient entry into the study site. In addition, not having stronger relationships with local organizations meant that we missed out on having a larger pool of prospective digital participants. To take from the marketing world, a successful digital project requires brand awareness and brand confidence (Michaels 2013). We had not established sufficient brand awareness or brand confidence. Moreover, the time and labor needed to improve our digital presence was too much for a group of three researchers with limited funding. (For more on digital labor, see Scholz 2012.) These missteps were problems of design and would be addressed internally. There were other, more external factors, that our ineffectiveness would lead us to consider further.

One external issue was the uneven and unidirectional use of social media for public engagement in local, civic, issues on our site. New York City began publishing a Digital Road Map (DRM) (2013) in 2011 as a vision for making New York “the number one digital city” in the US (1). One of the core tenets of the DRM is improving “digital engagement” by identifying “the right technology and tool to reach their constituency and achieve their aims” (27). As such, the DRM defines engagement as a unidirectional activity in which governing bodies see themselves as information disseminators for a public composed of consumers. This runs contrary to our own understanding of public engagement, in which participants are seen as active and equally legitimate.

As I mentioned earlier, about 42% of people in the US use social media for some form of political engagement. Still, of those 42%, the largest group of users are white males under 50 years of age (Rainie, Smith, Schlozman, Brady & Verba 2012). Among our co-researchers and interview participants (N= 23), there was varying interest in and experience with the use of social media for public and political engagement. Participants who were under 30 years of age reported that they primarily used Instagram, and they used it primarily to connect with their friends and family. They expressed not having used social media for political or public engagement very much. These patterns mirror national trends in social media use (Duggan 2013).

Participants over 30 were more varied. Some noted being digitally engaged, primarily through Facebook and Twitter, while others stated that they were on social media (mostly Facebook), but rarely used it for either public or personal engagement. Anecdotally, one interviewee in the over-30 group, who reported he was “old school” and didn’t use email and social media very much, noted that Twitter was vital to promoting a proposal he worked on for the Participatory Budgeting Project (PBP) in his district. PBP is a community-focused project through which ten city districts are deciding, along with district residents, how to spend $14 million (PBNYC n.d.). The most recent PBP evaluation report focuses on how organizers engaged local residents and advocates, but makes little mention of the role of social media (Community Development Project at the Urban Justice Center 2013). Still, this interviewee’s comments made clear that the potential impact of social media for public engagement is understood and used by local advocates, but it is not necessarily a part of the practice of the broader neighborhood.

In addition, we found that the local school district did not use a website or social media to engage the public. Parents at one local school did request that the school use a mass text (SMS) tool to provide families with more school updates. There were also a few individual schools that used Twitter to reach out to families. In sum, our data suggests that using social media for public engagement was not a common practice across East Harlem, and this potentially reproduced inequities of voice in political decision-making. Equitable engagement was further inhibited by an unclear vision of digital practices among local institutions and government bodies. In the future, #BarrioEdProjwould like to conduct a broader neighborhood survey to document how social media is used in the neighborhood as a way to contribute to developing a neighborhood vision for engagement through social media.

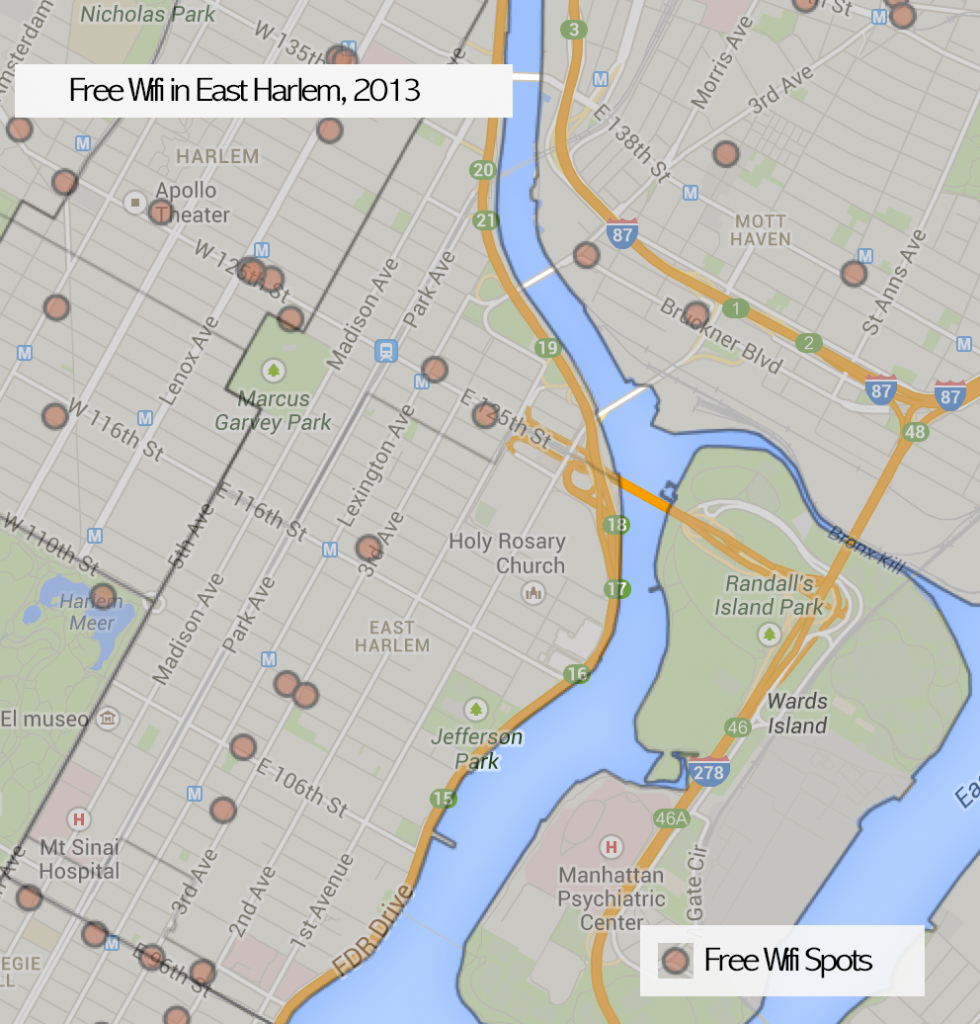

A final external factor I want to highlight concerns digital infrastructure and specifically access and adoption of high-speed broadband. According to Digital Road Map (2013), 99% of New Yorkers have residential access to high speed broadband, 300,000 more low income residents had access to broadband in 2013 than in 2011, there are fifty parks with free Wifi, and the city has served 4,000 resident living in public housing (NYCHA) through its digital van initiative (New York City, 3).

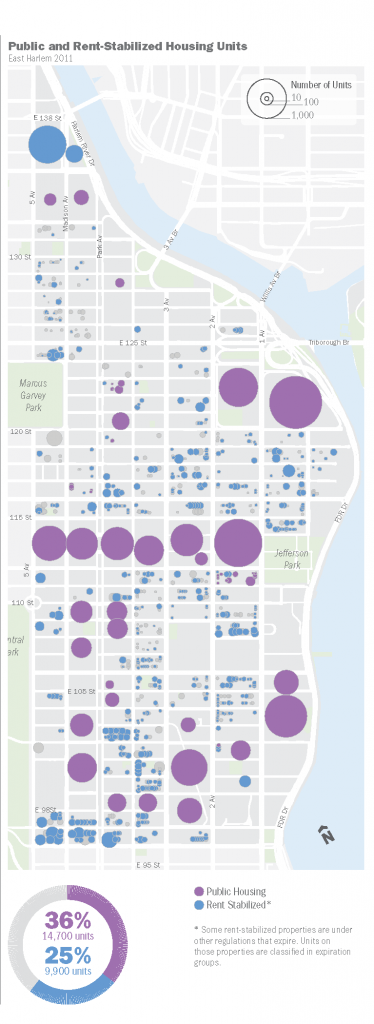

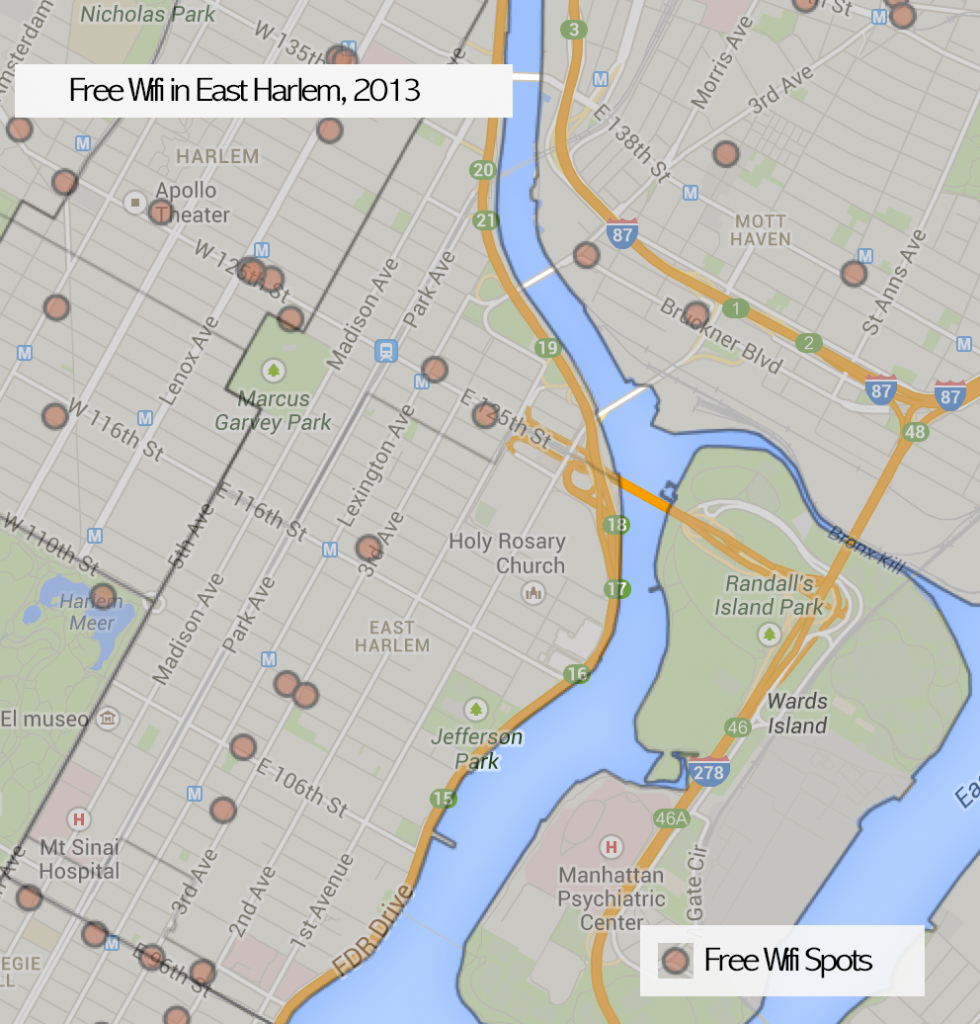

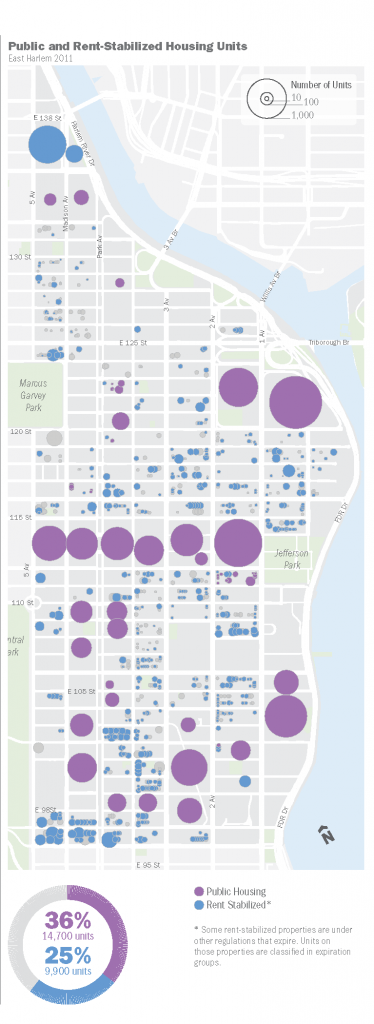

Certainly, these advances are positive, but the DRM leaves open a number of questions concerning the scope of these improvements. For example, questions about broadband access and broadband adoption must be asked. Nationally, consistency of access to broadband remains varied, though more narrowly, along geographic, racial/ethnic, and social class lines, and types of social media used vary along age and educational levels (Zickuhr 2013). East Harlem is still a low-income, primarily of-Color neighborhood where 31% of people live in poverty and twenty-four public housing projects (14,700 units) make up large parts of the landscape (Figure 3). According to NYC Open Data maps (New York City 2014), there are very few public Wifi spots available in East Harlem, including McDonald’s restaurants and the local libraries (see Figure 3).

Certainly, these advances are positive, but the DRM leaves open a number of questions concerning the scope of these improvements. For example, questions about broadband access and broadband adoption must be asked. Nationally, consistency of access to broadband remains varied, though more narrowly, along geographic, racial/ethnic, and social class lines, and types of social media used vary along age and educational levels (Zickuhr 2013). East Harlem is still a low-income, primarily of-Color neighborhood where 31% of people live in poverty and twenty-four public housing projects (14,700 units) make up large parts of the landscape (Figure 3 Map of EH-NYCHA Housing 2). According to NYC Open Data maps (New York City 2014), there are very few public Wifi spots available in East Harlem, including McDonald’s restaurants and the local libraries (Figure 4 Map of wifi spots).

Figure 3. Public and Rent Stabilized Housing Units Map, East Harlem 2011, from Regional Planning Association. (2012). East Harlem Affordable Housing Under Threat: Strategies for Preserving Rent-Regulated Units.

Figure 3. Public and Rent Stabilized Housing Units Map, East Harlem 2011, from Regional Planning Association. (2012). East Harlem Affordable Housing Under Threat: Strategies for Preserving Rent-Regulated Units.

Figure 4. Free Wifi in East Harlem, map created through NYC Open Data. #BarrioEdProj collection.

Figure 4. Free Wifi in East Harlem, map created through NYC Open Data. #BarrioEdProj collection.

The two public parks with Wifi are not mentioned in the map, nor are some of the other small businesses that offer Wifi (openwifispots 2014). Still, limited Wifi access intersects with the poor conditions of East Harlem libraries (Anderson 2014), and the neighborhood has one of the lowest levels of parkland per resident in the city (Chaban 2012). Additionally, as a neighborhood with one of the highest densities of public housing in New York (Hunter 2014), disparities in access to computers and the Internet are particularly stark (Wall 2012). The 4,000 people served by the NYCHA Digital Vans city-wide make up a very small percentage of the 178,557 residents that comprised NYCHA’s conventional housing program in March 2014 (New York City Housing Authority 2014). All this suggests that public access remains underdeveloped, leaving low-income residents with limited options for adopting broadband. Adoption is primarily mediated by financial constraints, including “high monthly fees, [h]ardware costs, hidden fees, billing transparency, quality of service, and availability” (Dailey, Bryne, Powell, Karaganis & Chung 2010, 3). At this point, data about access to and adoption of high speed broadband in East Harlem is not available, and is something that we also want to address in future surveying.

Looking back to move #BarrioEdProj Forward

While we were struggling with the social media aspects of the work, the digitally mediated research aspects of our D+CPAR process were flourishing educationally and affectively. Our community-centered historical work involved collectively reading relevant texts, conducting and producing digital interviews, and collaboratively analyzing data. Having been members of the East Harlem community for most if not all of their lives, Honory and Mariely were being exposed to East Harlem-focused social science and archival information for the first time. This elicited feelings of surprise and dissatisfaction. They were pleased to learn some of the rich history of the neighborhood, but at the same time they were disappointed by the way these histories had been denied to them over the course of their educational career. There was also a growing anger as they began to recognize the devastating impact of gentrification and education reform on their lives and the lives of others in the neighborhood.

As a research group, we took our new understanding into interviews, where we heard from a cadre of multigenerational community stakeholders who had participated in the historical moments we had been studying. The interviews would have an emotional effect on the participants and the researchers. Interviewees in the under-30 group, for example, mentioned that being asked about their community was an educational experience for them. Gentrification was a notion that most were familiar with, but they appeared to find the opportunity to link their abstract notion of gentrification to their own lives a positive experience. Participants in the over-30 group also mentioned that they appreciated being able to share their perspective. One participant also noted that she appreciated the mission of #BarrioEdProj and saw it as a potential space to “light a spark” for change.

Upon returning to our group meetings we would engage in a reflective process to make sense of what we observed in the interviews in relation to our readings, archival work, and our subjects’ lived experience. In these discussions the voices of generations of East Harlem education community members enlivened the very complicated situations residents dealt with as they faced displacement from home, urban restructuring, and disconnections from levers of power within the state education apparatus. For our co-researcher Honory, for example, seeing a parent discuss struggles over education led her to think about the complexities families face and the necessary work parents must do in order to provide high quality education for all children.

Figure 5. Meibell Contreras, parent of children at Central Park East I (CPE I). Ms. Contreras discusses her engagement with the schools and some of her concerns about the system. #BarrioEdProj Vimeo Collection.

What was happening in these more personally connected aspects of the work was as much emotional as it was scholarly. As Lynch (2009) reminds us, humans are “deeply relational beings, part of a complex matrix of social and emotional relations that often give meaning and purpose to life, even though they can also constrain life’s options” (4). This historical and interview-based work was where trust amongst participants was built and the purpose of work was most clearly defined.

Making sense of all the data we had collected and the emotional highs and lows we had experienced, the question we asked ourselves was fundamentally one about taking action: The community is in trouble, so how can we help people realize what’s going on? We were thinking about what engagement would look like and how digital media might or might not fit into this aspect of the work. This was the point at which Mariely importantly noticed that “technology was not working in El Barrio.” In the months that followed we began to develop short-term and long-term changes in our design. First, we decided that we wanted to create a newsletter to report our data, posting it in our digital platforms and holding a public forum to share the newsletter. Second, we decided to slow down our social media efforts and turn our attention to organizing and expanding our digital content and doing more on-the-ground relationship-building with various community stakeholders.

We hoped these changes would help us find ways to scale up some of the transformative experiences that we had had within our historical work. Moreover, our digital engagement efforts needed stronger roots in the community and better, more compelling content, before it could gain traction in East Harlem and beyond. As such, our D+CPAR framework would include a digital, participatory, archival component that would serve as a springboard for digital engagement. Digital, participatory archiving is a growing area that is seen as scholarly, educational, and political work (Caswell 2014, Povinelli 2011). This activist archiving has been particularly important for humanities and social science scholars who study populations and histories that have traditionally been marginalized and rendered invisible to the public. Like our supporting organization, East Harlem Preservation, our goal is to not only document histories, but to use those histories to inform the public and bring people together to incite change.

Conclusion

The first year of the #BarrioEdProj sheds light on some of the promises and challenges that public social science researchers must consider in the digital age. What became evident was that digital critical participatory action research (D+CPAR) provides opportunities to reimagine qualitative research methods, offers new perspectives on what and how data can be collected, and expands how data can be shared and discussed. Our project also brought attention to the importance of public engagement as the nature of engagement is changing. In addition, old barriers like relational trust and new barriers like broadband access and adoption in under-resourced communities present engaged scholars with challenges that can be addressed through collective, interdependent efforts that are socio-politically and financially supported—all solutions that existed long before the digital came into vogue. What is distinct about this era, and what I think researchers must be most vigilant about, is how the digital must explicitly be part of our understanding of the terrain of struggle. As Murthy (2008) notes:

[t]he challenge for us is not only to adapt to new research methods, but also, as Saskia Sassen (2002: 365) stresses, to ‘develop analytic categories that allow us to capture the complex imbrications of technology and society’. Doing these in tandem, with an eye to ethics and the digital divide, will be the benchmarks by which sociology’s engagement with new media technologies will be judged.

As new critical participatory projects begin to take root and digital media are integrated into projects, research collectives must continue to interrogate how digital media shapes the everyday as the everyday shapes the digital. #BarrioEdProj looks to community-based projects like the Red Hook Initiative’s Digital Stewards program and academic endeavors like JustPublics@365 as examples of work that centers the imbrications of technology and society. We contend that by working through an analytical and activist framework that sees the digital as part of the fabric of social inequity and social justice, D+CPAR can contribute to the production of holistic research and a more just and sustainable future.

Bibliography

Anderson, Trevor. 2014. “A Tale of Two Libraries | NY City Lens.” City Lens. http://nycitylens.com/2014/04/a-tale-of-two-libraries/.

Anyon, Jean. 2009. Theory and Educational Research: Toward Critical Social Explanation. New York: Routledge. OCLC 191445993

Bilandzic, Mark, and John Venable. 2011. “Towards Participatory Action Design Research: Adapting Action Research and Design Science Research Methods for Urban Informatics.” The Journal of Community Informatics 7 (3). OCLC 780993480

Boyatzis, Richard E. 1998. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. OCLC 38096870

Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. OCLC 441355434

Buras, Kristen L. 2011. “Race, Charter Schools, and Conscious Capitalism: On the Spatial Politics of Whiteness as Property (and the Unconscionable Assault on Black New Orleans).” Harvard Educational Review 81 (2): 296–331. OCLC 748837945

Carroll, John M., and Mary Beth Rosson. 2007. “Participatory Design in Community Informatics.” Design Studies 28 (3). Participatory Design: 243–61. OCLC 4928976538

Caswell, Michelle, Mallick, Samip. 2014. “Collecting the Easily Missed Stories: Digital Participatory Microhistory and the South Asian American Digital Archive.” Archives and Manuscripts Archives and Manuscripts, 1–14. OCLC 5575923213

Chaban, Matt. 2012. “El Barrio’s Secret Gardens: East Harlem Has Some Unexpected Parks, But It Still Needs Better Ones.” New York Observer. http://observer.com/2012/10/east-harlem-open-space-index-new-yorkers-for-parks/.

Community Development Project at the Urban Justice Center. 2013. “A People’s Budget: A Research and Evaluation on Participatory Budgeting in New York City”. New York, NY. http://www.cdp-ny.org/report/pbreport_year2.pdf.

Dailey, Dharma, Amelia Bryne, Alison Powell, Joe Karaganis, and Jaewon Chung. 2010. “Broadband Adoption in Low-Income Communities — Publication — Social Science Research Council”. Social Science Research Council. http://www.ssrc.org/publications/view/1EB76F62-C720-DF11-9D32-001CC477EC70/.

Dávila, Arlene M. 2004. Barrio Dreams: Puerto Ricans, Latinos, and the Neoliberal City. Berkeley: University of California Press. OCLC 55661006

Economic and Social Research Council. 2014. “Digital Social Research | ESRC | The Economic and Social Research Council.” Economic and Social Research Council. Accessed April 28. http://www.esrc.ac.uk/research/research-methods/dsr.aspx.

Fliegel, Seymour, and James MacGuire. 1993. Miracle in East Harlem: The Fight for Choice in Public Education. New York: Times Books. OCLC 27188294

Flores, Juan. 1997. “The Latino Imaginary: Dimensions of Community and Identity.” In Tropicalizations: Transcultural Representations of Latinidad, edited by Frances R. Aparicio and Susana Chávez-Silverman. Dartmouth. OCLC 644944379

Freidenberg, Judith. 1995. The Anthropology of Lower Income Urban Enclaves: The Case of East Harlem. New York, N.Y.: New York Academy of Sciences. OCLC 32013248

Gándara, Patricia., and Frances Contreras. 2009. The Latino Education Crisis the Consequences of Failed Social Policies. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London: Harvard University Press. OCLC 225874263

Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. 2008. “Forgotten Places and the Seeds of Grassroots Planning.” In Engaging Contradictions: Theory, Politics, and Methods of Activist Scholarship, by Charles R. Hale. Berkeley: University of California Press. OCLC 190597164

Gurstein, Michael. 2000. Community Informatics Enabling Communities with Information and Communications Technologies. Hershey, Pa.: Idea Group Pub. OCLC 45731044

———. 2007. What Is Community Informatics (and Why Does It Matter)? Monza, Italy: Polimetrica. OCLC 729337371

Hale, Charles R. 2008. “Introduction.” In Engaging Contradictions: Theory, Politics, and Methods of Activist Scholarship, edited by Charles R. Hale. Berkeley: University of California Press. OCLC 190597164

Horton, Myles, Paulo Freire, Brenda Bell, John Gaventa, and John Peters. 1990. We Make the Road by Walking: Conversations on Education and Social Change. Reprint edition. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. OCLC 21483166

Hunter, Willa. 2014. “CIVITAS News: Talking Past and Future for East Harlem.” CIVITAS News. http://civitasnyc.blogspot.com/2014/03/talking-past-and-future-for-east-harlem.html.

Jung, E. Alex. 2014. “Wages for Facebook.” Dissent. http://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/wages-for-facebook.

JustPublics@365. 2013. “AltMetrics.” JustPublics@365. https://justpublics365.commons.gc.cuny.edu/altmetrics/.

Leonard, Sarah, and Kate Losse. 2014. “Introduction: Our Technology and Theirs.” Dissent. http://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/introduction-16.

Lipman, Pauline. 2011. The New Political Economy of Urban Education: Neoliberalism, Race, and the Right to the City. New York: Routledge. OCLC 712653276

Lipman, Pauline, and David Hursh. 2007. “Renaissance 2010: The Reassertion of Ruling-Class Power through Neoliberal Policies in Chicago.” Policy Futures in Education 5 (2): 160–78. OCLC 424909813

Lykes, M.B., and A Mallona. 2008. “Towards Transformational Liberation: Participatory Action Research and Activist Praxis.” In The SAGE Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice, edited by Peter Reason and Hilary Bradbury. Los Angeles, Calif.; London: SAGE. OCLC 474540732

Lynch, Kathleen. 2009. “Affective Equality: Who Cares?” Development 52 (3): 410–15. OCLC 832753614

Meier, Deborah. 1995. The Power of Their Ideas: Lessons for America from a Small School in Harlem. Boston: Beacon Press. OCLC 31433890

Melamed, Jodi. 2011. Represent and Destroy: Rationalizing Violence in the New Racial Capitalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. OCLC 719427973

Michaels, Sharon. 2013. “10 Ways to Better Brand Recognition.” http://www.forbes.com/sites/womensmedia/2013/04/16/10-ways-to-better-brand-recognition/.

Morales, Ed. forthcoming. “Latino Core Communities in Change: The Erasing of an Imaginary Nation.” In Latin@s in New York: Communities in Transition, edited by Angelo Falcon and Gabriel. Haslip-Viera. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame.

Morales, Ed, and Laura. Rivera. 2009. Whose barrio? The gentrification of East Harlem. New York: Ed Morales.

Murthy, Dhiraj. 2008. “Digital Ethnography An Examination of the Use of New Technologies for Social Research.” Sociology 42 (5): 837–55. OCLC 438515369

New York City. 2013. “New York City’s Digital Leadership: 2013 Roadmap.” http://www.nyc.gov/html/static/pages/roadmap/DigitalRoadmap_2013.pdf.

———. 2014. “NYC Open Data.” NYC Open Data. https://data.cityofnewyork.us/.

New York City Housing Authority. 2014. “Fact Sheet.” http://www.nyc.gov/html/nycha/html/about/factsheet.shtml.

Nieto, Sonia. 2000. Puerto Rican Students in U.S. Schools. Sociocultural, Political, and Historical Studies in Education. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. OCLC 476207183

NYC IBO. 2013. “New York City Public School Indicators: Demographics, Resources, Outcomes”. New York, NY: New York City Independent Budget Office. http://www.ibo.nyc.ny.us/iboreports/2013educationindicatorsreport.pdf.

openwifispots. 2014. “Free WiFi Hotspots Wi-Fi Cafes Coffee Shops Hotels Wireless Airports (what Is Wifi).” OpenWiFiSpots.com. May 7. http://www.openwifispots.com/Finder.aspx?Longitude=-73.945415&Latitude=40.800225#40.794961963254806,-73.94352672485353,14.

Orr, Marion, and John Rogers. 2011. Public Engagement for Public Education: Joining Forces to Revitalize Democracy and Equalize Schools. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. OCLC 595739032

Padilla, Andrew. 2012. El Barrio Tours (Gentrification In East Harlem) Trailer. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o3ar5etBIbc&feature=youtube_gdata_player.

PBNYC. 2014. “Participatory Budgeting in New York City | REAL MONEY. REAL PROJECTS. REAL POWER.” Accessed May 5. http://pbnyc.org/.

Pedraza, Pedro. 1997. “Puerto Ricans and the Politics of School Reform.” Centro: Journal of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies Centro: Journal of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies 9 (1): 74–85. OCLC 66690404

POLLING FOR JUSTICE Part 1 of 3. 2010. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mh0mdefVPHc&feature=youtube_gdata_player.

Povinelli, Elizabeth A. 2011. “The Woman on the Other Side of the Wall: Archiving the Otherwise in Postcolonial Digital Archives.” Differences 22 (1): 146–71. OCLC 719510167

Prensky, Marc. 2014. “H. Sapiens Digital: From Digital Immigrants and Digital Natives to Digital Wisdom.” Accessed May 2. http://www.wisdompage.com/Prensky01.html.

Rainie, Lee, Aaron Smith, Lehman Schlozman, Henry Brady, and Sidney Verba. 2012. “Social Media and Political Engagement.” Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project. http://www.pewinternet.org/2012/10/19/social-media-and-political-engagement/.

Robinson, Cedric J. 1983. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. London; Totowa, N.J.: Zed ; Biblio Distribution Center. OCLC 11259946

Scholz, Trebor. 2012. Digital Labor: The Internet as Playground and Factory. New York: Routledge. OCLC 707966602

Smith, Aaron. 2011. “The Social Side of the Internet.” Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project. http://www.pewinternet.org/2011/01/18/the-social-side-of-the-internet/.

Spiro, Lisa. 2014. “Defining Digital Social Sciences.” Dh+lib. http://acrl.ala.org/dh/2014/04/09/defining-digital-social-sciences/.

Terras, Melissa M, Julianne Nyhan, and Edward Vanhoutte. 2013. Defining Digital Humanities: A Reader. OCLC 855582159

Torre, María Elena, Michelle Fine, Brett G. Soudt, and Madeline Fox. 2012. “Critical Participatory Action Research as Public Science.” In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, edited by Harris M. Cooper and Paul Marc Camic. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. OCLC 759695958

Underberg, Natalie M, and Elayne Zorn. 2013. Digital Ethnography: Anthropology, Narrative, and New Media. Austin: University of Texas Press. OCLC 802103176

Wall, Patrick. 2012. “Mobile Computer Labs Deliver High-Speed Internet to Public Housing – Claremont.” DNAinfo.com New York. http://www.dnainfo.com/new-york/20120808/claremont/mobile-computer-labs-deliver-high-speed-internet-public-housing.

Watters, Julie, and Savanna Comeau. 2010. “Participatory Action Research: An Educational Tool for Citizen-Users of Community Mental Health Services.”

Young, Iris Marion. 1997. Intersecting Voices : Dilemmas of Gender, Political Philosophy, and Policy. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. OCLC 36241704

Zickuhr, Kathryn. 2013. “Who’s Not Online and Why.” Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project. http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/09/25/whos-not-online-and-why/.

About the Author

Edwin Mayorga is a parent and educator-scholar-activist who is completing his doctoral work in Urban Education at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. His dissertation, Education in our Barrios #BarrioEdProj, is a digital critical participatory action research project (D+CPAR) based in the New York City Latino core community of East Harlem. Working with two youth co-researchers (Mariely Mena and Honory Peña), #BarrioEdProj traces the discursive and material effects of neoliberal education reform and urban restructuring on, in, and through East Harlem and New York City since the 1970s. Most recently, he was a co-author of “Slow violence and neoliberal education reform: Reflections on a school closure” and “Scholar-activism: A twice told tale.” In the fall of 2014, he will be an Assistant Professor in the Educational Studies department at Swarthmore College. Edwin does educational justice work with the New York Collective of Radical Educators (NYCoRE), is a participant in the National Latino Education Research & Policy Project (NLERAP), and on the community advisory board of the Participatory Action Research Center for Education Organizing (PARCEO). You can find Edwin on Twitter @chinolatino78 and @barrioedproj.