Talking Heads, “Once In a Lifetime” (1981)

Much actual and virtual ink has been spilled over the past few years recounting how the field of Digital Humanities came into being. As a social historian and someone who has been involved in digital work of one sort or another since the mid 1970s, I am somewhat bemused by what Geoffrey Rockwell has aptly termed the “canonical Roberto Busa story of origin” offered by English department colleagues (Rockwell 2007). That canonical DH history usually starts with the famous Father Roberto Busa developing his digital concordances of St. Thomas Aquinas’s writings beginning in 1949 (the first of which was published in 1974) with critical technical support provided by Thomas Watson, head of IBM.[1] It quickly moves from there to recount the emergence of humanities computing (as it was originally known) in the 1980s, followed by the development of various digitized literary archives launched by literary scholars such as Jerry McGann (Rossetti) and Ed Folsom (Whitman) in the 1990s (Hockey 2004). In this recounting, academics in English, inspired by Father Busa, pushed ahead with the idea of using computers to conceive, create, and present the digital concordances, literary editions, and, ultimately, fully digitized and online archives of materials, using common standards embodied in the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI), which was established in 1987.[2] The new field of Digital Humanities is said to have emerged after 2004 directly out of these developments in the literary studies field, what Willard McCarty terms “literary computing” (McCarty 2011, 4).[3]

As a historian who believes in multi-causal explanations of historical phenomena (including what happens intellectually inside of universities), I think there are alternative interpretations of this origin story that help reveal a much more complicated history of DH.[4] I will argue in this piece that the history field—particularly historians working in its social, public, and quantitative history sub-fields—also made a substantial and quite different contribution to the emergence of the Digital Humanities that parallels, at times diverges from, and even anticipates the efforts of literary scholars and literary studies.[5] I will first sketch broader developments in the social, public, and quantitative history sub-fields that began more than four decades ago. These transformations in the forms and content of historical inquiry would ultimately lead a group of historians to contribute to the development of DH decades later. I will also use my own evolution over this time period (what I dub in the title of this piece my “premature” Digital Humanism), first as a social and labor historian, then as a media producer, digital historian, and finally now as a teacher of digital humanities and digital pedagogy, to illustrate the different pathways that led many historians, myself included, into contributing to the birth and evolution of the Digital Humanities. I will use my ongoing collaborations with my colleagues at the American Social History Project (which I co-founded more than 35 years ago) as well as with Roy Rosenzweig and the Center for History and New Media to help tell this alternate DH origins story. In the process, I hope to complicate the rather linear Father Busa/humanities computing/TEI/digital literary archives origin story of DH that has come to define the field.

Social and Labor History

Social history first emerged in the pre-World War II era with the founding in 1929 in France of the Annales school of historical inquiry by Lucien Febvre and Marc Bloch and carried forward by Fernand Braudel in the 1950s and Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie in the 1970s. The field of social history found fertile new ground in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s. The “new” social history was very much a product of the rejection of traditional political history narratives and a search for new methodologies and interdisciplinary connections. Social history examined the lives and experiences of “ordinary people”—workers, immigrants, enslaved African Americans, women, urban dwellers, farmers, etc.—rather than the narrow focus on the experiences of Great White Men that had dominated both academic and popular history writing for decades if not centuries. This changed historical focus on history “from the bottom up” necessitated the development of new methodological approaches to uncover previously unused source materials that historians needed to employ to convey a fuller sense of what happened in the past. Archives and libraries had traditionally provided historians access to large collections of private and public correspondence of major politicians, important military leaders, and big businessmen (the gendered term being entirely appropriate in this context) as well as catalogued and well-archived state papers, government documents, and memoirs and letters of the rich and famous. But if the subject of history was now to change to a focus on ordinary people, how were historians to recount the stories of those who left behind few if any traditional written records? New methodologies would have to be developed to ferret out those hidden histories.[6]

The related sub-field of labor history, which, like social history, was also committed to writing history “from the bottom up,” illustrates these methodological dilemmas and possibilities. Older approaches to US labor history had focused narrowly on the structure and function of national labor unions and national political parties, national labor and party leaders, and what happened in various workplaces, drawing on government reports, national newspapers, and union records. The new labor history, which was pioneered in the early 1960s, first by British Marxist historians such as Eric Hobsbawm and E. P. Thompson, sought to move beyond those restricted confines to tell the previously unknown story of the making of the English working class (to appropriate the title of one of Thompson’s most important works). Hobsbawm and especially Thompson relied heavily in their early work on unconventional local and literary sources to uncover this lost history of English working people. The new labor history they pioneered was soon adapted by US labor historians, including David Montgomery, David Brody, and Herbert Gutman and by graduate students, deploying an array of political and cultural sources to reveal the behaviors and beliefs of US working people in all of their racial and ethnic diversity. The new US labor history embraced unorthodox historical methodologies including: oral history; a close focus on local and community studies, including a deep dive into local working-class newspapers; broadened definitions of what constituted work (e.g. women’s housework); and working-class family and community life and self-activity (including expressions of popular working-class culture and neighborhood, political, and religious associations and organizations). I committed myself to the new labor history and its innovative methodologies in graduate school at UCLA in the early 1970s when I began to shape my doctoral dissertation, which sought to portray the ways black, white, and immigrant coal miners in the West Virginia and Colorado coal fields managed to forge interracial and interethnic local labor unions in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Brier 1992).

Public History

A second activist and politically engaged approach to communicating historical scholarship—public history—also emerged in the 1970s. Public history grew in parallel to and was made possible by the new academic field of social history. To be sure, while social history spoke largely to the history profession, challenging its underlying methodological and intellectual assumptions, public history and the people who self-identified as public historians often chose to move outside the academy, embedding themselves and their public history work inside unions, community-based organizations, museums, and political groups. Public historians, whether they stayed inside the academy or chose to situate themselves outside of it, were committed to making the study of the past relevant (to appropriate that overused Sixties’ phrase) to individuals and groups that could and would most benefit from exposure to and knowledge about their “lost” pasts (Novick 1988, 512–21).

Public history’s emergence in the mid-1970s signaled that at least one wing of the profession, albeit the younger, more radical one, was committed to finding new ways and new, non-print formats to communicate historical ideas and information to a broad public audience through museum exhibits, graphic novels, audio recordings and radio broadcasts, and especially film and television. A range of projects and institutions that were made possible by this new sub-field of public history began to take shape by the late 1970s. I worked with fellow radical historians Susan Porter Benson and Roy Rosenzweig and the three of us put together in 1986 the first major collection of articles and reports on US public history projects and initiatives. Entitled Presenting the Past, the collection was based on a special theme issue of the Radical History Review (the three of us were members of the RHR editorial collective) that we had co-edited five years earlier.[7] Focusing on a range of individual and local public history projects, Presenting the Past summarized a decade of academic and non-academic public history work and projects in the United States (Benson, Brier, and Rosenzweig 1986).[8]

Stephen Robertson, who now heads the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media (CHNM)[9] at George Mason University, has correctly noted, in a widely read 2014 blog post,[10] that we can and should trace the origins of the much newer sub-field of digital history, a major contributor to the Digital Humanities’ growth, to the public history movement that was launched a quarter century earlier (Robertson 2014). Robertson goes on to suggest that this early focus on public history led digital historians to ask different questions than literary scholars. Historians focused much more on producing digital history in a variety of presentational forms and formats rather than literary scholars’ emphasis on defining and theorizing the new Digital Humanities field and producing online literary archives. This alternative focus on public presentations of history (i.e., intended for the larger public outside of the academy and the profession) may explain why digital historians seem much less interested in staking out their piece of the DH academic turf while literary scholars seem more inclined both to theorize their DH scholarship and to assert that DH’s genesis can be located in literary scholars’ early digital work.

Quantitative History

A third, and arguably broader, methodological transformation in the study and writing of US history in these same years was the emergence of what was called quantitative history. “Cliometrics” (as some termed it, a bit too cutely) held out the possibility of generating new insights into historical behavior through detailed analyses of a myriad of historical data available in a variety of official sources. This included, but was certainly not limited to, raw data compiled by federal and state agencies in resources like census manuscripts.[11] Quantitative history, which had its roots in the broader turn toward social science taken by a number of US economic historians that began in the late 1950s, had in fact generated by the early 1970s a kind of fever dream among many academic historians and their graduate students (and a raging nightmare for others) (Thomas 2004).[12] Edward Shorter, a historian of psychiatry (!), for example, authored the widely-read The Historian and The Computer: A Practical Guide in 1971. Even the Annales school in France, led by Ladurie, was not immune from the embrace of quantification. Writing in a 1973 essay, Laurie argued that “history that is not quantifiable cannot claim to be scientific” (quoted in Noiret 2012). Quantitative history involved generating raw data from a variety of primary source materials (e.g., US census manuscripts) and then using a variety of statistical tools to analyze that data. The dreams and nightmares that this new methodology generated among academic historians were fueled by the publication of two studies that framed the prominence and ultimate eclipse of quantitative history: Stephan Thernstrom’s Poverty and Progress, published in 1964, and Robert Fogel and Stanley Engerman’s Time on the Cross, which appeared a decade later (Thernstrom 1964; Fogel and Engerman 1974).

Thernstrom’s study used US census manuscripts (the original hand-coded forms for each resident produced by census enumerators) from 1850 to 1880 as well as local bank and tax records and city directories to generate quantitative data, which he then coded and subjected to various statistical measures. Out of this analysis of data he developed his theories of the extent of social mobility, defined occupationally and geographically, that native-born and Irish immigrant residents of Newburyport, Massachusetts enjoyed in those crucial years of the nation’s industrial takeoff. The critical success of Thernstrom’s book helped launch a mini-boom in quantitative history. A three-week seminar on computing in history drew thirty-five historians in 1965 to the University of Michigan; two years later a newsletter on computing in history had more than 800 subscribers (Graham, Milligan, and Weingart 2015). Thernstrom’s early use of quantitative data (which he analyzed without the benefit of computers) and the positive critical reception it received helped launch the quantitative history upsurge that reshaped much US social and urban history writing in the following decade. Without going into much detail here or elaborating on my own deep reservations about Thernstrom’s methodology[13] and the larger political and ideological conclusions he drew from his analysis of the census manuscripts and city directories, suffice it to say that Thernstrom’s work was widely admired by his peers and emulated by many graduate students, helping him secure a coveted position at Harvard in 1973.[14]

The other influential cliometric study, Fogel and Engerman’s Time on the Cross, was widely reviewed (including in Time magazine) after it appeared in early 1974. Though neither author was a social historian (Fogel was an economist, Engerman an economic historian), they were lavishly praised by many academics and reviewers for their innovative statistical analysis of historical data drawn from Southern plantation records (such as the number of whippings meted out by slave owners and overseers to enslaved African Americans). Their use of statistical data led Fogel and Engerman to revise the standard view of the realities of the institution of slavery. Unlike the conclusions reached by earlier historians such as Herbert Aptheker and Kenneth Stampp that centered on the savage exploitation and brutalization of slaves and their active resistance to the institution of slavery, Fogel and Engerman concluded that the institution of slavery was not particularly economically inefficient, as traditional interpretations argued, that the slaves were only “moderately exploited,” and that they were only occasionally abused physically by their owners (Aptheker 1943 [1963]; Stampp 1956 [1967]). Time on the Cross was the focus of much breathless commentary both inside and outside of the academy about the appropriateness of the authors’ assessments of slavery and how quantitative history techniques, which had been around for several decades, would help historians fundamentally rewrite US history.[15] If this latter point sounds eerily prescient of the early hype about DH offered by many of its practitioners and non-academic enthusiasts, I would argue that this is not an accident. The theoretical and methodological orthodoxies of academic disciplines are periodically challenged from within, with new methodologies heralded as life- (or at least field-) changing transformations of the old. Of course, C. Vann Woodward’s highly critical review of Fogel and Engerman in the New York Review of Books and Herbert Gutman’s brilliant book-length takedown of Time on the Cross soon raised important questions and serious reservations about quantitative history’s limitations and its potential for outright distortion (Woodward 1974; Gutman 1975; Thomas 2004). Gutman’s and Woodward’s sharp critiques aside, many academic historians and graduate students (myself included) could not quite resist dabbling in (if not taking a headlong plunge into) quantitative analysis.

Using a Computer to do Quantitative History

Though I had reservations about quantitative history—my skepticism stemming from a general sense that quantitative historians overpromised easy answers to complex questions of historical causation—I decided to broaden the fairly basic new labor history methodology that I was then using in my early dissertation research, which had been based on printed historical sources (government reports, nineteenth-century national newspaper accounts, print archival materials, etc.). I had been drawn to coal miners and coal mining unionism as a subject for my dissertation because of the unusual role that coal miners played historically as prototypical proletarians and labor militants, not only in the United States, but also across the globe. I was interested in understanding the roots of coal miners’ militancy and solidarity in the face of the oppressive living and working conditions they were forced to endure. I also wanted to understand how (or even if) white, black, and immigrant mineworkers had been able to navigate the struggle to forge bonds of solidarity during trade union organizing drives. I had discovered an interesting amount of quantitative data in the course of my doctoral dissertation research: an enumeration of all coal strikes (1,410 in number) that occurred in the United States in the 1881–94 period detailed in the annual reports of the US Commissioner of Labor.[16] This was what we would now call a “dataset,” a term that was not yet used in my wing of the academy in 1975. This critical fourteen-year historical period witnessed the rise and fall of several national labor union organizations among coal miners, including the Knights of Labor, the most consequential nineteenth-century US labor organization, and the birth of the United Mine Workers of America, the union that continues to represent to this day the rapidly dwindling number of US coal miners.

In my collaboration with Jon Amsden, an economic and labor historian and UCLA faculty member, the two of us decided to statistically analyze this data about the behavior and actions of striking coal miners in these years. The dataset of more than 1,400 strikes statistically presented in large tables was simply too large, however, to analyze through conventional qualitative methods to divine patterns and trends. Amsden and I consequently made a decision in 1975 to take the plunge into computer-assisted data analysis. The UCLA Computer Center was a beehive of activity in these early years of academic computing, especially focused on the emerging field of computer science.[17] The center was using an IBM 360 mainframe computer, running Fortran and the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (the now venerable SPSS, originally released in 1968, and first marketed in 1975) to support social scientific analyses (Noiret 2012).

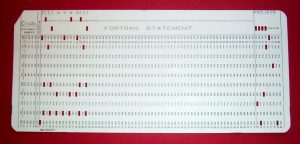

Amsden and I began by recording some of the characteristics involved in each of the 1,410 coal strikes that occurred in those 14 years: year of the strike, cause or objective of the strike, and whether a formal union was involved. To make more detailed comparisons we drew a one-in-five systematic random sample of the coal strikes. This additional sampled data included the number of workers involved in each strike, strike duration, and miners’ wages and hours before and after the strike. We laboriously coded each strike by hand on standard 80-character IBM Fortran coding sheets.

We then had a keypunch operator at the UCLA Computer Center (no doubt a woman, sadly unknown and faceless to us, righteous labor historians though we both were!)[18] transfer the data on each strike entry to individual IBM Fortran punch cards, originally known at Hollerith cards (Lubar 1992). That process generated a card stack large enough to carry around in a flat cardboard box the size of a large shoe box.

We regularly visited the UCLA Computer Center in the afternoon to have our card stack “read” by an IBM card reading machine and then asked the IBM 360 to generate specific statistical tabulations and correlations we requested, trying to uncover trends and comparative relationships among the data.[19] The nature of this work on the mainframe computer did not require us to learn Fortran (I know DHer Steve Ramsay would disapprove![20]), though Amsden and I did have to brush up on our basic statistics to be able to figure out how to analyze and make sense of the computer output. We picked up our results (the “read outs”) the next morning, printed on large, continuous sheets of fanfold paper.

It was a slow and laborious process, with many false starts and badly declared and pointless computing requests (e.g., poor choices of different data points to try to correlate).

Ultimately, however, this computerized data analysis of strike data yielded significant statistical correlations that helped us uncover previously unknown and only partially visible patterns and meanings in coal miners’ self-activity and allowed us to generate new insights (or confirm existing ones) into the changing levels of class consciousness exhibited by miners. Our historical approach to quantitative analysis was an early anticipation, if I can be permitted a bit of hyperbole, of Franco Moretti’s “distant reading” techniques in literary scholarship (Moretti 2005), using statistical methods to examine all strikes in an industry, rather than relying on a very “close reading” of one, two, or a handful of important strikes that most labor historians, myself included, typically undertook in our scholarly work. Amsden and I wrote up our results in 1975 and our scholarly article appeared in the Journal of Interdisciplinary History in 1977, a relatively new journal that featured interdisciplinary and data-driven scholarship. The article received respectful notice as a solid quantitative contribution to the field and was reprinted several times over the next three decades (Amsden and Brier 1977).[21]

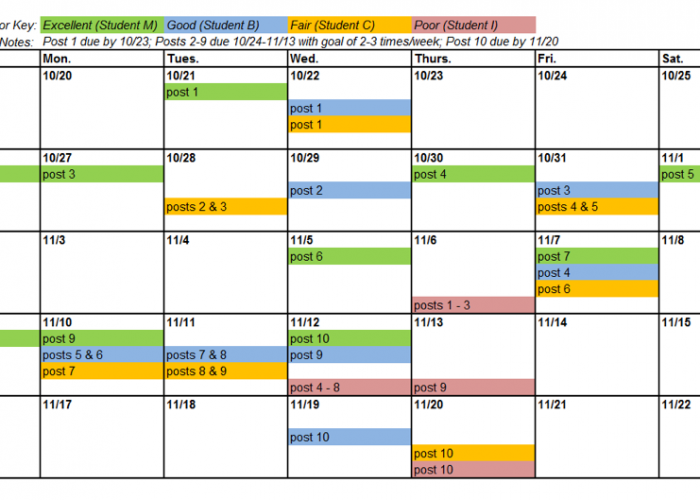

One of our key statistical findings was that the power and militancy of coal miners increased as their union organizations strengthened (no surprises there) and that heightened union power between 1881 and 1894 (a particularly contentious period in US labor history) generated more militant strikes in the coal industry. Our data analysis revealed that these militant strikes often moved away from narrow efforts to secure higher wages to allow miners across the country to pose more fundamental challenges to the coal operators’ near total control over productive relations inside coal pits. Below are two screen shots, both generated by SPSS, from the published article: a scatter diagram (a new technique for historians to employ, at least in 1975) and one of the tables. The two figures convey the kinds of interesting historical questions we were able to pose quantitatively and how we were able to represent the answers to those questions graphically.

Figure 5 above shows the growth in the number of multi-establishment coal strikes and the increasing number of mines involved in strike activity over time, a good measure of increasing union power and worker solidarity over the critical 14-year period covered in the dataset.

Table 3 employs a solidarity index that Amsden and I developed out of our analysis of the coal strike statistics, based on the ratio of the number of strikers to the total number of mine employees in a given mine whose workers had gone out on strike. The data revealed that union-called strikes were consistently able to involve a higher percentage of the overall mining workforce as compared to non-union strikes and with less variation from the norm. This table lay at the heart of why I had decided to study coal miners and their unions in the first place. I hoped to analyze why and how miners consistently put themselves and their unions at the center of militant working-class struggles in industrializing America. I might have reached some of these same conclusions by analyzing traditional qualitative sources or by looking closely at one or a handful of strikes. However, Amsden and I had managed to successfully employ a statistical analysis in new ways (at least in the history field) that allowed us to “see” these developments and trends in the data nationally and regionally. We were able therefore to argue that the evolving consciousness of miners over time was reflected in their strike demands and in their ability to successfully spread the union message across the country. I should note here that the United Mine Workers of America had become the largest union by far in these early years of the American Federation of Labor. In sum, we believed we had developed a new statistical methodology to analyze and understand late nineteenth-century working-class behavior. We had used a computer to help answer conceptual questions that were important in shaping our historical interpretation. This effort proved to be a quite early instance of the use of digital techniques to ask and at least partially answer key historical (and, by definition, humanities) questions.

From Quantitative History to the American Social History Project

Around the time of the 1977 publication of the coal miners on strike article I decided to follow my public history muse, morphing from a university-based history scholar and professor-in-training, albeit one who had begun to use new digital technologies, into an activist public historian. I had moved to New York City soon after completing the computer-aided project on coal mining strikes to learn how to produce history films. This was a conscious personal and career choice I made to leave the academy to become an independent filmmaker. My commitment to historical ideas having a greater public and political impact drove my decision to change careers. On my first job in New York in 1977 as research director for a public television series of dramatic films on major moments in US labor history I met Herbert Gutman, one of the deans of the new labor and social history whose work I had read and admired as a graduate student. I spent the next two years researching and producing historical documentaries and other kinds of dramatic films.

Two years after meeting Gutman I was invited by Herb, who taught at the CUNY Graduate Center, to co-teach a summer seminar for labor leaders for which he had secured funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). The NEH summer seminars, in an innovative combination of academic and public history, were designed to communicate to unionized workers the fruits of the new social and labor history that Herb had done so much to pioneer and to which I had committed my nascent academic career in graduate school at UCLA. With the success of these summer seminars, which we taught at the CUNY Graduate Center in 1979 and 1980, Gutman and I decided to create the American Social History Project (ASHP) at CUNY. We reasoned that reaching 15 workers each summer in our seminars, though immensely rewarding for all involved (including the two teachers), was not as efficient as creating a new curriculum that we could make available to adult and worker education programs and teachers across the country. The project quickly received major grants in 1981 and 1982, totaling $1.2 million, from the NEH and the Ford Foundation, and under Herb’s and my leadership we rapidly hired a staff of a dozen historians, teachers, artists, and administrators to create a multimedia curriculum, entitled “Who Built America?” (WBA?). The curriculum mixed the writing of a new two-volume trade book focused on working people’s contributions to US history with a range of new multimedia productions (initially 16mm films and slide/tape shows, VHS videos and, later, a range of digital productions, including two Who Built America? CD-ROMs and several web sites such as “History Matters”). ASHP also had a second, clear orientation, in addition to developing multimedia materials: We built a vibrant education program that connected the project in its first few years with CUNY community college faculty and also New York City high school teachers who used our media materials (including specially designed accompanying viewer guides) in their classes that helped deepen and refine Who Built America?’s pedagogical impact on students. We hoped this multimedia curriculum and ASHP’s ongoing engagement with teachers would broaden the scope and popular appeal of working-class and social history and would be widely adopted in high school, community college, and worker education classrooms around the country as well as by the general public.[22]

I should note here that my early exposure to electronic tools, including being a “ham” radio operator and electronics tinkerer in high school in the early 1960s and using mainframe computers at UCLA in 1975, inclined me to become an early and enthusiastic adopter of and proselytizer for personal computers when they became publicly available in the early 1980s. I insisted in 1982, for example, against resistance from some of my ASHP colleagues who expected to have secretarial help in writing and editing their WBA? chapter drafts, that we use personal computers (I was Kaypro II guy!) to facilitate the drafting and editing of the Who Built America? textbook, work on which began that year (ASHP 1990, 1992).[23]

ASHP stood outside of the academic history profession as traditionally understood and practiced in universities at that time. As a grant-funded, university-based project with a dozen staff members, many of us with ABDs in history who worked on the project full-time (not on traditional nine-month academic schedules), ASHP staff were clearly “alt-ac”ers several decades before anyone coined that term. We wore our non-traditional academic identities proudly and even a bit defiantly. Gutman and I also realized, nonetheless, that ASHP needed a direct link to an academic institution like CUNY to legitimize and to establish an institutional base that would allow the project to survive and thrive, which led us to instantiate ASHP inside of CUNY. The American Social History Project, in fact, celebrated its 35th anniversary in CUNY in October 2016.[24] That was a consequential decision, obviously, since ASHP might not have survived without the kind of institutional and bureaucratic support that CUNY (and the Graduate Center) have provided over the past three and a half decades. ASHP, at the same time, also stood outside of the academic history profession in believing in and in producing our work collaboratively, which militated against the “lone scholar in the archive” cult that still dominates most academic scholarship and continues to fundamentally determine the processes of promotion and tenure inside the academy. Public history, which many ASHP staff members came out of, had argued for and even privileged such collaborative work, which in a very real sense is a precursor to the more collaborative work and projects that now define much of the new digital scholarship in the Digital Humanities and in the “alt-ac” careers that have proliferated in its wake. Well before Lisa Spiro (2012) enumerated her list of key DH “values”—openness, collegiality and connectedness, diversity, and experimentation—we had embodied those very values in how we structured and operated the American Social History Project (and continue to do so), a set of values that I have also tried to incorporate and teach in all of my academic work ever since.

ASHP’s engagement with collaborative digital work began quite early. In 1990 we launched a series of co-ventures with social historian Roy Rosenzweig (who had been a valued and important ASHP collaborator from the outset of the project a decade earlier, including as a co-author of the Who Built America? textbook) and Bob Stein, the head of The Voyager Company, the pioneering digital publisher. Roy and I had begun in the late 1980s to ruminate about the possibilities of computer-enhanced historical presentations when Bob Stein approached me in 1990 with a proposal to turn the first volume of the WBA? trade book (which had just been published) into an electronic book (ASHP 1990).[25] Applying the best lessons Roy and I and our ASHP colleagues had learned as public historians who were committed to using visual, video, audio, and textual tools and resources to convey important moments and struggles in US history, we worked with Voyager staff to conceive, design, and produce the first Who Built America? CD-ROM in 1993, covering the years 1876 to 1914 (ASHP 1993).[26] As noted earlier, our use of multimedia forms was an essential attribute that we learned as practitioners of public history, a quite different orientation than that relied on by literary DHers who work with text analysis.

The disk, which was co-authored by Roy Rosenzweig, Josh Brown, and me, was arguably the first electronic history book and one of the first e-books ever to appear. The WBA? CD-ROM won critical popular acclaim and a number of prestigious awards, inside in the academy and beyond (Thomas 2004). It also generated, perhaps because of its success, a degree of political notoriety when its inclusion by Apple in the tens of thousands of educational packs of CD-ROMs the company gave away to K-12 schools that purchased Apple computers in 1994-95 led to a coordinated attack on WBA?, ASHP, and Apple by the Christian Right and the Moral Majority. The Radical Right was troubled by the notion conveyed in several of the literally hundreds of primary historical documents we included in the CD-ROM that “gay cowboys” might have been involved in the “taming” of the West or that abortion was common in early twentieth-century urban America. The right-wing attacks were reported in the mainstream press, including the Wall Street Journal and Newsweek.

The Right, however, ironically failed in all the furor to notice the CD-ROM’s explicitly pro-worker/anti-capitalist politics! The Right tried to get Apple to remove the WBA? CD-ROM from the education packs, but Apple ultimately backed ASHP and WBA?, though only after much contention and negative publicity.[27]

Despite this political controversy, the first WBA? CD-ROM and early historical web projects like Ed Ayers’s Civil War-era The Valley of the Shadow (1993) helped imagine new possibilities for digital scholarship and digital presentations of historical work. I would suggest that the appearance of the first WBA? CD-ROM nearly a quarter century ago was one of the pioneering instances of the new digital history that contributed a decade later to the emergence of the Digital Humanities, making Roy, Josh, and me and our ASHP colleagues what I have termed in the title of this article and elsewhere in print “premature digital humanists.”[28] That said, I do believe we missed an opportunity to begin to build connections to other scholars outside of history who were undertaking similar digital work around the same time that we completed the WBA? CD-ROM in 1993. Jerry McGann, for example, was beginning his pioneering work at the University of Virginia on the Rossetti Archive and was writing his landmark study “The Rationale of HyperText” (McGann 1995). And while we became aware of each other’s work over the next half dozen years, we never quite came together to ponder the ways in which our very disparate disciplinary approaches to digital scholarship and presentation might have productively been linked up or at least put into some kind of active dialogue. As a result, digital history and digital literary studies occupied distinct academic silos, following quite different paths and embracing very different methodologies and ideas. And neither digital history nor digital literary studies had much in common with the digital new media artists who were also working in this same period and even earlier, grouped around the pioneering journal Ars Electronica.[29] This was a missed opportunity that I believe has hindered Digital Humanities from being more of a big tent and, more importantly, allowing it to become a more robust interdisciplinary force inside the academy and beyond.

In any case my digital history colleagues and I continued to pursue our own digital history work. Roy Rosenzweig, who taught at George Mason University, founded the Center for History and New Media in 1994 a year after the first WBA? CD-ROM appeared. Our two centers next collaborated on several award-winning digital history projects, including the History Matters website mentioned earlier, which made many of the public domain primary source documents presented originally in the WBA? CD-ROM available online. This proved to be a particularly useful and accessible way for teachers at both the high school and college levels to expose their students to a rich array of primary historical sources. And, following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks in New York and Washington, DC, our two centers were invited by the Sloan Foundation to collaborate on the development of the September 11 Digital Archive (9/11DA). As Josh Brown and I argued in an article on the creation of the 9/11DA, September 11th was “the first truly digital event of world historical importance: a significant part of its historical record—from e-mail to photography to audio to video—was expressed, captured, disseminated, or viewed in (or converted to) digital forms and formats” (Brier and Brown 2011, 101). It was also one of the first digital projects to be largely “crowdsourced,” given our open solicitation of ordinary people’s digital reminiscences, photos, and videos of the events of September 11th and its aftermath. As historians faced with the task of conceiving and building a brand new digital archive from scratch that focused on a single world historical event, we were also forced to take on additional roles as archivists and preservationists, something we had previously and happily left to professional librarians. We had to make judgments about what to include and exclude in the 9/11 archive, how and whether to display it online, how to contextualize those resources, and, when voluntary online digital submissions of materials by individuals proved insufficient to allow us to offer a fully-rounded picture of what happened, how to target particular groups (including Muslims, Latinos, and the Chinese community in lower Manhattan) with special outreach efforts to be able to include their collective and individual stories and memories in the 9/11DA. Our prior work in and long-term engagement with public history proved essential in this process. We ended up putting the archive online as we were building it, getting the initial iteration of the site up on the web in January 2002 well before the lion’s share of individual digital submissions started pouring in. The body of digital materials that came to constitute the September 11 Digital Archive ultimately totaled nearly a quarter million discrete digital items, making it one of the largest and most comprehensive digital repositories of materials on the September 11 attacks.[30]

While literary scholars confront similar issues of preservation of and access to the materials they are presenting in digital archives, they usually have had the good fortune to be able to rely on extant and often far more circumscribed print sources as the primary materials they are digitizing, annotating, and presenting to fellow scholars and the general public. Public historians who are collecting digital historical data to capture what happened in the recent past or even the present, as we were forced to do in the September 11 Digital Archive, do not have the luxury of basing our work on a settled corpus of information or data. We also faced the extremely delicate task of putting contemporary people’s voices online, making their deepest and most painful personal insights and feelings available to a public audience. Being custodians of that kind of source material brings special responsibilities and sensitivities that most literary digital humanists don’t have to deal with when constructing their digital archives. Our methodologies and larger public imperatives as digital historians are therefore different from those of digital literary scholars. This is especially true given our commitment in the 9/11DA and other digital history archiving projects like the CHNM’s “Hurricane Digital Memory Bank” (on the devastating 2005 Gulf Coast hurricanes Katrina and Rita), as well as ASHP’s current CUNY Digital History Archive project. The latter focuses on student and faculty activism across CUNY beginning in the late 1960s and on presenting historical materials that are deeply personal and politically consequential.[31]

It is important to note that while ASHP continued to collaborate on several ongoing digital history projects with CHNM (headed first by Dan Cohen and Tom Scheinfeldt after Roy’s death in 2007, and, since 2013, by Stephen Robertson), the two centers have moved in different directions in terms of doing digital history. CHNM’s efforts have focused largely on the development of important digital software tools. CHNM’s Zotero, for example, is used to help scholars manage their research sources, while its Omeka software offers a platform for publishing online collections and exhibitions. CHNM has also established a strong and direct connection to the Digital Humanities field, especially through its THATCamps, which are participant-directed digital skills workshops and meetings.[32] On the other hand, ASHP has stayed closer to its original purpose of developing a range of well curated and pedagogically appropriate multimedia historical source materials for use by teachers and students at both the high school and college levels, intended to help them understand and learn about the past. Emblematic of ASHP’s continuing work are The Lost Museum: Exploring Antebellum American Life and Culture and HERB: Social History for Every Classroom websites as well as Mission US, an adventure-style online series of games in which younger players take on the role of young people during critical moments in US history.[33]

From ASHP to ITP and the Digital Humanities

I moved on in my own academic career after formally leaving ASHP as its executive director in 1998, though I remained actively involved in a number of ongoing ASHP digital projects. These included the development of a second WBA? CD-ROM, covering the years from 1914 to 1946, which was published in 2001 (ASHP 2001) and is still available, as well as the aforementioned 9/11 Digital Archive and the CUNY Digital History Archive. As I morphed over three decades from analog media producer, to digital media producer, to digital archivist/digital historian, I became keenly aware of the need to extend the lessons of the public and digital history movements I helped to build to my own and my graduate students’ classroom practices. That was what drove me to develop the Interactive Technology and Pedagogy (ITP) certificate program at the CUNY Graduate Center in 2002. My goal was to teach graduate students that digital tools offered real promise beyond the restricted confines of academic research in a single academic field to help us reimagine and to reshape college classrooms and the entire teaching and learning experience, as my ASHP colleagues and I began doing more than 30 years ago with the Who Built America? education program. I always tell ITP students that I take the “P” in our name (“Pedagogy”) as seriously as I take the “T” (“Technology”) as a way to indicate the centrality of teaching and learning to the way the certificate program was conceived and has operated. I have coordinated ITP for almost 15 years now and will be stepping down as coordinator at the end of the spring 2017 term. I believe that the program has contributed as much to digital pedagogy and to the Digital Humanities as anything else I’ve been involved in, not only at the CUNY Graduate Center where I have been fortunate to have labored for almost all of my academic career, but also in the City University of New York as a whole.[34] One of the ITP program’s most important and ongoing contributions to the Digital Humanities and digital pedagogy fields has been the founding in 2011 of the online Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy, which is produced twice-yearly and is directed by an editorial collective of digital scholars and digital pedagogues, including faculty, graduate students, and library staff.

Working with faculty colleagues like Matt Gold, Carlos Hernandez, Kimon Keramidas, Michael Mandiberg, and Maura Smale, with many highly motivated and skilled graduate students (too numerous to name here), and committed digital administrators and leaders like Luke Waltzer, Lisa Brundage, and Boone Gorges, as well as my ongoing work with long-time ASHP colleagues and comrades Josh Brown, Pennee Bender, Andrea Ades Vasquez, and Ellen Noonan, I have been blessed with opportunities to help create a robust community of digital practice at the Graduate Center and across CUNY. This community of scholars and digital practitioners has helped develop a progressive vision of digital technology and digital pedagogy that I believe can serve as a model for Digital Humanities work in the future. Though far from where I began forty years ago as a doctoral student with an IBM 360 computer and a stack of Fortran cards, my ongoing digital work at CUNY seems to me to be the logical and appropriate culmination of a career that has spanned many identities, including as a social and labor historian, public historian, digital historian, digital producer, and, finally, as a digital pedagogue who has made what I hope has been a modest contribution to the evolution and maturation of the field of Digital Humanities.